Abstract

Since the ICPD in 1994, the Government of Indonesia has struggled with the challenge of providing sexual and reproductive health education to adolescents. Following an attempt at a family-centred approach, a pilot project was carried out in Central and East Java to train peer educators, coordinated by the National Family Planning Coordinating Board (BKKBN). A total of 80 peer educators (male/female teams) carried out small-group information sessions in ten different districts. Over 1,300 adolescents attended in all. Forty peer counsellors in 20 teams then carried out five outreach sessions each in their communities, attended by nearly 4,000 adults and adolescents. Educators chosen were older in age, knowledge level, authority and communication skills than adolescents, but were well accepted as mentors. Adolescents wanted to know how to deal with sexual relationships and feelings, unwanted pregnancy and STDs. With 42 million Indonesian adolescents needing information, the government cannot produce enough manuals to satisfy demand. New strategies are required to put information in the public domain, e.g. via the media. The approach described in this paper would probably be beyond the staffing and resource capacity of most districts in Indonesia. Nonetheless, it shows that there was great enthusiasm across a variety of communities for efforts to educate young people on protecting their reproductive health.

Résumé

Depuis la Conférence internationale sur la population et le développement en 1994, le Gouvernement indonésien s'efforce de dispenser une éducation en santé génésique aux adolescents. Après une tentative centrée sur la famille, un projet pilote a été mené à Java pour former des éducateurs des pairs, sous la direction du Conseil national de coordination de la planification familiale. Quatre-vingts éducateurs de pairs (équipes masculines/féminines) ont tenu des séances d'information en petits groupes dans dix districts différents. Plus de 1300 adolescents y ont pris part. Quarante équipes d'éducateurs ont ensuite organisé cinq séances chacune dans leurs communautés, auxquelles ont participé 4000 adultes et adolescents. Les éducateurs choisis étaient plus âgés, avaient davantage de connaissances, d'autorité et de compétences en communication que les adolescents, mais étaient bien acceptés comme mentors. Les adolescents voulaient s'informer sur les relations sexuelles et les sentiments, les grossesses non désirées et les MST. L'Etat ne peut produire suffisamment de manuels pour satisfaire la demande des 42 millions d'adolescents que compte le pays et il doit trouver de nouvelles stratégies pour mettre les informations dans le domaine public, par exemple par les médias. L'approche décrite ici dépasserait probablement les capacités en effectifs et ressources de la plupart des districts indonésiens. Néanmoins, elle a montré que beaucoup de communautés accueillaient avec enthousiasme les activités d'éducation des jeunes pour la protection de leur santé génésique.

Resumen

Desde la CIPD de 1994, el Gobierno de Indonesia ha tratado de proporcionar educación sexual y reproductiva a los adolescentes. Tras un intento de crear un enfoque centrado en la familia, se realizó un proyecto piloto en Java Central y Oriental, coordinado por la junta coordinadora del Programa de Planificación Familiar Nacional (BKKBN), para capacitar a los educadores de pares. Un total de 80 educadores (equipos de hombres y mujeres) realizaron sesiones de información en grupos pequeños en diez distritos. Asistieron más de 1300 adolescentes. Cuarenta equipos de educadores de pares realizaron cinco sesiones de extensión en su comunidad, a las cuales asistieron unos 4000 adultos y adolescentes. Estos educadores eran de edad más avanzada y poseı́an más conocimientos, más autoridad y mejores habilidades de comunicación que los adolescentes, pero todos fueron aceptados como mentores. Los adolescentes querı́an saber cómo lidiar con relaciones sexuales, el embarazo no deseado y las ETS. Dado que 42 millones de adolescentes indoneses necesitan información, el gobierno no puede producir suficientes manuales para satisfacer la demanda. Para ello, se necesitan nuevas estrategias, como difusión por los medios de comunicación. El enfoque aquı́ descrito probablemente sobrepasarı́a la capacidad de personal y recursos de la mayorı́a de los distritos del paı́s. No obstante, diversas comunidades demostraron gran entusiasmo por esforzarse para educar a la juventud respecto a la protección de su salud reproductiva.

When Indonesia signed on to the 1994 ICPD Programme of Action in Cairo, one of the great concerns among the officials in the government delegation was the issue of premarital sexuality. For many years the family planning programme had resisted calls to provide clinical services for sexually active adolescents. There was a deep belief that knowledge of contraception would promote immoral behaviour among the young, and that the only appropriate interventions should be entirely “knowledge-based”. By this, they meant that young people might be told about contraception but they should not be offered any services, even if they were sexually active. Not surprisingly, the designers of interventions in Indonesia, including the authors, were much older than the target population, and frequently had personal histories that differed markedly from contemporary youth. For the most conservative officials charged with implementing the programmes on the ground, even the display of condoms in retail shops and discussion of contraceptive pills in the mass media could be objectionable and provoke unmarried youngsters to experiment sexually. Cairo represented a direct challenge to such beliefs, and a vindication of the arguments of progressive educators who saw ignorance as the real danger to the sexual health of the young. With ICPD, the basic paradigm shaping attitudes toward the reproductive health needs of the young changed, and the Indonesian family planning programme moved cautiously into planning more explicit sex education programmes for children and adolescents.

This paper offers a critical reflection on our work on programmes for adolescents and young people, to address the reproductive health challenges they face. It attempts to draw lessons for Indonesia and reflect on the applicability of the approaches discussed here for other programmes.

Bringing the ICPD Programme of Action home

When the Indonesian delegation returned from Cairo in 1994 they brought a message of pride and determination. The pride came from confirmation of the nation's success in implementing an effective birth control programme. The determination was sparked by the realisation that the implementation of the Programme of Action would require new initiatives addressing men's reproductive health, reproductive rights and especially the needs of adolescents. Government officials and academics pointed to the large cohorts of adolescents and the long-term rising age at marriage as major challenges for a programme that had previously focused exclusively on married couples.

At first the National Family Planning Coordinating Board (BKKBN) tested programmes that would equip parents to teach their own children about reproductive health and sexuality. They imagined that putting information in schools or on television would provoke opposition among conservative religious leaders, so they directed that the interventions be made via parents, as part of their rights and responsibilities within the family. However, this policy was also a reflection of the difficulty officials felt in dealing with these issues themselves. A “family-centred approach” was developed in 1995 at the Centre for Health Research at the University of Indonesia, led by Dr Meiwita Budiharsana Iskandar, following guidelines set out by BKKBN. It involved manuals and training sessions to prepare parents to communicate with their teenage children.

Unfortunately, the family was uniquely difficult as an arena for providing knowledge to the young, and these efforts encountered serious obstacles. Parents reported feeling awkward talking about sex with their sons and daughters. Issues of menstruation and masturbation were painfully embarrassing, particularly to fathers. The researchers found that parents took great interest in the written materials, but more for their own information than for any realistic possibility of discussion with children. Similarly, teenagers said it was easier to talk to their friends or extended family members than their own parents. Across the archipelago, strong incest taboos and strict rules of propriety and filial respect placed discussion of sexuality out of bounds of the nuclear family. By 1996 it was clear from the pilot activities that this approach was unlikely to reach the majority of young people.

Seeking innovations for adolescent programmes

In 1997 the World Bank funded an intervention to improve reproductive health in Central and East Java, called the Safe Motherhood Partnerships and Family Approach Project, involving five government departments–health, family planning, education, religion and social affairs. All of these departments sought to promote reproductive health for youth, but prior to this project they lacked a common concept and common workers reaching out to young people. The BKKBN was the key coordinating agency, tying together the activities of the five departments. From 1997 to 1999 they struggled with the question of how to reach out to adolescents. Their problems were exacerbated when in 1997–98 the economic crisis and the fall of the New Order government led to a total restructuring of government. The Head of BKKBN was promoted and his replacement, Dr Ida Bagus Oka, fearing that women would not be able to afford contraceptives, adopted a back-to-basics approach that sidelined activities related to youth. Timely development of social safety nets prevented declines in contraceptive availability, and then elections in 1999 brought in the Wahid administration and the appointment of Khofifah Indar Parawangsa as Minister for Women's Empowerment and Head of BKKBN.

Under Khofifah's leadership, many of the sensitivity barriers to programme development were removed. Coming from a religious school background and a political party associated with the large Nahdlatul Ulama religious organisation, her religious credentials were unquestionable. When she spoke out in favour of women's rights and the need for greater responsibility of men for contraceptive use, she did not attract condemnation from conservative elements. Under her stewardship the BKKBN was able to broaden thinking about a wide range of programmatic issues, including serving the needs of youth.

In 2001 the Safe Motherhood Partnerships and Family Approach Project invited the Indonesian AIDS Foundation to collaborate on an innovative activity called Empowering Adolescents as Peer Educators and Peer Counsellors. Hasmi and Widyantoro were principals in the initiative and took the lead in a design intended to move away from the purely family-centred approach. Hasmi was Director for Adolescent and Reproductive Rights Protection at BKKBN and Widyantoro was working as a consultant for the Indonesian AIDS Foundation, an NGO with both experience and commitment to tackling the issue of youth sexuality. The basic concept was to train individuals to become peer educators (Pendidik Sebaya) and peer counsellors (Konselor Sebaya) who would work in paired teams, male and female, to provide information, advice and printed materials to fellow adolescents. They would not provide clinical services for adolescents, as that was still regarded as beyond the tolerance level of local communities. However, the individuals recruited for the project were experienced in running NGO clinics and youth programmes, and set positive role models and a pragmatic approach to support young people to the extent possible.

Testing of the peer educator approach was limited to the two provinces where the project was working. If successful, the model would be applied nationwide. Ten districts were selected for a pilot programme,Footnote* two of which are on the island of Madura, regarded as a stronghold of religious conservatism. If the programme worked there, it was felt that it could work anywhere in the country.

Those appointed to develop the pilot project were charged with identifying an equal number of young men and women with a high level of communication skills to act as peer educators. Using a battery of tests and interviews, they found that the applicants who best met the selection criteria were largely over 18 years of age and had already graduated from high school.

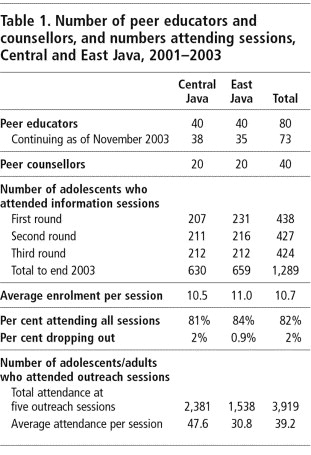

A total of 80 peer educators in 40 male/female teams were chosen and spread across five districts each in Central and East Java . Only seven of the 80 recruited had dropped out by November 2003, usually for reasons of marriage, continuing education or moving away for work.

Table 1 Number of peer educators and counsellors, and numbers attending sessions, Central and East Java, 2001–2003

They were trained by experts from Jakarta and the local areasFootnote† and charged with carrying out three rounds of small group information sessions, consisting of six weekly sessions with 10–12 participants each from schools, clubs or neighbourhoods. Sessions were designed to be active, and maintain a high degree of interest and concentration among the participants. They used teaching materials (flip-charts and manuals) developed by the Indonesia AIDS Foundation, BKKBN and other government departments, covering sexual development; sexual behaviour; pregnancy, contraception and abortion; reproductive tract infections and STDs; abusive behaviour and violence; and drug and alcohol abuse. In Central Java, the sessions tended to grow in size over time, while in East Java they became smaller. Over 1,300 adolescents attended in all. Less than 2% of the adolescents who signed up at the first session failed to complete the course and over 80% attended all six sessions.

The best peer educators were then trained as peer counsellors for the second phase of activities. These peer counsellors, in 20 male/female teams, conducted public meetings for both young people and other community members to introduce the concept of counselling and service interventions to promote healthy behaviours among young people. These outreach sessions were meant to validate their role as voluntary workers in the community with the skills to deal with anxieties about the behaviour of young people, and in most cases this succeeded. When adults were in the audience, the questions were likely to focus on the dangers of drugs and protecting children from unsafe sex. When the audience was exclusively adolescents, the sessions could sometimes become raucous, with questions about “normal” behaviour, contraception and romance. From 2001 to 2003, the peer counsellors carried out at least five outreach sessions each in their communities . Across the ten districts nearly 4,000 people attended these sessions, with an average of 40 per session.

From the outset, peer educators were supervised and assisted by professionals recruited from cooperating community institutions, including medical doctors, psychologists and senior teachers. Project coordinators from the BKKBN were also available to assist them to gain community respect and cooperation.

Networking among peer educators and peer counsellors was encouraged to promote communication and links with local health centres, rehabilitation centres, schools, religious institutions, family planning volunteers, social workers, youth groups and NGOs. This provided support for the peer educators and avenues for referral of adolescents with specific problems. While not stated directly, it also opened the door, however slightly, for sexually active young people to get contraceptive services, and for unintended and unwanted pregnancies to be discreetly referred to safe abortion or adoption services. However, as numerous discussions with the peer educators indicated, even if the door is opened a crack, most of the messages from local leaders were that it should not be pushed or it might be slammed altogether.

Evaluating the peer educator project

Between 2001 and 2003 there were numerous internal and external evaluations of the project by BKKBN and government agencies. The BKKBN concluded that there was strong local support for adolescent reproductive health education. The findings reflected high levels of community and government anxiety about child marriage, premarital sex, generation gaps, illegal drugs and the HIV epidemic. The belief was that education would change behaviour and overcome the negative consequences of disease and illegitimacy.

As the completion of the project in December 2003 approached, the BKKBN and the Indonesian AIDS Foundation wanted to assess the experience of the peer educators and counsellors. Were they really as successful as appeared in operational evaluations? Were they sustainable? Could they be adopted in settings lacking financial resources on the scale provided by World Bank loans? Hull and colleagues from the BKKBN put these questions to officials, community leaders, peer educators and peer counsellors, and adolescents in four of the districts (Jepara, Rembang, Sampang, and Pamekasan) in mid-2003. They visited government and religious schools, youth groups and local religious leaders to collect personal reactions to the information and outreach sessions, and the role of the peer educators and peer counsellors.

In all four districts, there was widespread enthusiasm for the programme among the peer educators and counsellors and the adolescents they educated. Religious leaders and youth groups made it clear that communities were hungry for increased education on issues of sexuality and reproductive health. A number of older religious leaders emphasised the need to prepare youth to meet the challenges of a rapidly changing world, in which the risks associated with sex could be fatal.

Peer educators were not actually “peers”

The answer to the question of who constitutes a peer and who might confidently be entrusted to educate adolescents may or may not converge in the same person. Certainly in the four districts visited, the selected peer educators and counsellors were not age-group peers of the 15–19 year-olds who attended sessions, and there was no hope of any age-group peers of 10–14 year-olds ever being recruited if the approach were extended in 2004 to cover junior high school.

While a few peer educators and counsellors were adolescents, the majority were older. Some were already married and living in a world far from the high school playground. In one of the districts the age range was 22 to 35, and this was not untypical. They were older both in age and knowledge level and exceptional in communication skills and social status, all of which gave them much more authority than same-age peers could ever have had. They might better be described as mentors.

Thus, the project developed in directions that ignored the original concept of age-mates in order to achieve a practical outcome. There was no attempt to modify the name or the goals of the project when experience in the field indicated that the original notion was impractical. In retrospect, it seems obvious that Javanese 15–19 year-olds generally lack the authority or the self-confidence to carry out such a project. Some outstanding adolescents did participate effectively, but they relied on the older group members who could provide support, guidance and political protection.

While this might be interpreted as a major shortcoming of a project purporting to promote peer education, what made these mentors acceptable to adolescents was that they were not parents, teachers, religious leaders, bureaucrats, or police. They were not judging the behaviour of the adolescents nor condemning the questions raised during discussions. They were not distant in lifestyle or language. But most of all, they were not avoiding a discussion of issues that concerned young people struggling to define their romantic and sexual lives.

The discussions and questions at youth groups could be disarmingly frank, once educators were found to have knowledge of reproductive health matters. The peer counsellors in particular asked the evaluation team for advice on how to assist with problems such as a young man who was having sex with the statue of a woman, a young man who was masturbating in the marketplace and young boys at a bus station who were rent-a-boys for local men and needed medication for STDs.

The evaluation team also identified dangerous traditional and modern practices which are not covered in any of the current manuals. In all the areas, 90% of boys and a majority of girls were circumcised. Two types of herbal preparations were widely used by young women, one to bring on menstruation in cases of unwanted pregnancy and another to cause vaginal drying or tightening for having sex.

Lastly, the practice of hazing in junior and senior high schools is deeply embedded and according to some of the peer educators, violence in the schoolyard is used to justify sexual and gender-based exploitation and violence in other arenas. These practices pose problems that need to be addressed in training manuals, group discussions and locally organised public campaigns for adolescent reproductive health.

The peer educators and peer counsellors were not trained to provide medical or psychological services. While they might be tempted to address the moral dimensions of the issues, they had no particular standing to do so and they certainly did not have the medical training to advise on clinical issues. They needed clear instructions to refer young people to institutions involved in adolescent reproductive health in their area, such as the youth-friendly community health clinics (Puskesmas peduli remaja), trained teachers at schools and professional social workers and counsellors in local government.

As regards actual adolescent reproductive health needs, few peer educators or other members of the project were able to describe the extent of premarital sexuality, unwanted pregnancy, domestic violence or drug use in their own regions. While they were totally convinced that these were important problems, their conviction came from slogans on government or NGO posters rather than information about the dimensions of the problems locally. Thus, efforts by local governments to collect and analyse social and health data are necessary for such projects in future.

Attempts to train age-group peers as ongoing educators would have been doomed to budgetary failure in any case. Each year, the rising cohorts disappear from schools and youth groups, becoming young adults, developing careers and marrying. The cost of constantly training new cohorts of adolescents to sustain the project would have absorbed the resources needed to address more pressing issues of health in poor communities.

This still leaves the question of whether the project could have had teams of trained mentors who recruited and supported small groups of peer educators. The review team met with some who had done just that, and in the process had gone beyond the original project design to strengthen local activities. There were also cases of counsellors who set up phone-in programmes on local radio stations, and in this way connected more regularly and effectively with adolescents in their locality.

We concluded, however, that it is better to train and maintain groups of educators, paramedics, doctors and midwives based in youth-friendly institutions. Their commitment would guarantee returns for much longer than a year or two. Peer educators and counsellors who were “mentors” or “youth advocates”, as in our pilot study, selected and trained locally, could still have an important role, but they would be part of a larger team committed to adolescent reproductive health.

Content of educational and training materials

Educators and counsellors in the pilot areas were very interested in reading about adolescent reproductive health issues and commonly expressed the desire for more and varied written information. Were they able to get the information they needed?

In fact, project personnel had access to masses of material: BKKBN manuals directed at young people, parents and teachers from the family-centred approach, those specifically written for the current project, and some 25 manuals prepared by the Department of National Education for use in schools and in non-formal education by other government departments, funded by the World Bank, UNFPA or USAID, these were all colorful, but relatively expensive, productions.

Project designers often ignore the private sector, despite the obvious fact that commercial ventures produce a vast amount of printed material purporting to teach young people about sexuality. Urban bookstores sell Indonesian language texts providing advice to teenagers and their parents. These may be direct translations from other languages (often unauthorised by the copyright holder), compilations of Indonesian newspaper advice columns or pamphlets written by local doctors or sexologists. Despite this huge range of publications, it is still common for intervention programmes to suggest preparation of a new manual as the first step of any activity, purpose-written to carry forward innovative approaches. Certainly the reason we felt the peer educator project needed new materials was to ensure that the content matched the project goals and activities.

Such publications raise questions about the appropriate role for a central government office in satisfying information needs of adolescents. Indonesia has a long tradition of producing manuals for health and family planning. The earliest family planning booklet was printed in the 1930s in Central Java. Even earlier there were booklets warning young people of the dangers of immoral behaviour and STDs. Medical doctors and intellectuals in the 1950s produced a steady stream of marriage manuals with advice on sexuality and birth control. Since that time literally hundreds of guides and manuals have been written, most recently heavily funded by donors. These efforts have become a mini-industry for programme officials, donors and NGOs, but have often contained contradictory and confusing information and had tiny print-runs and poor distribution systems. A joke told in Indonesia is that it is easier to find an Indonesian government sex education handbook in Washington DC than in Jakarta, and impossible to find it in any schools. On the other hand, our peer educators said they had access to a wide variety of publications found in the local marketplace or in bookshops in nearby towns.

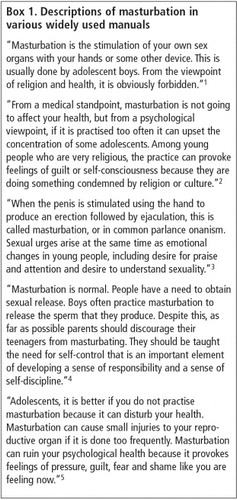

Government materials have to go through vetting processes and committees that reflect many different interests. The problem is that there is a lack of consistency in the tone and content of the manuals and training materials used by the peer educators. When we looked through the manuals in the local offices of the project, we found some strange contradictions in the collections.

The earliest project pamphlets prepared by BKKBN in 1998–2000 for adolescents and parents were largely compilations of biology lessons and moral injunctions, offering little practical advice. The one for parents instructs them to tell their children that masturbation is forbidden by both religion and modern medical advice, that it is a sin for children to marry without the permission of their parents, that anal and oral sex are mostly practised by homosexual people and that constant religious education and tight supervision are the appropriate ways to prevent immoral activities and promote reproductive health.

Over time the content of manuals has changed as new strategies and priorities emerged. Early guides for adolescents often concentrated on warning of the dangers involved in sexual life, be it STDs, rape or the insidious effects of drugs and alcohol. Information on STDs, for example, offered no advice on what might be involved in diagnosis and treatment or where to obtain help.Footnote*

There was little discussion of relationships, and nothing about the fact that sex can be pleasurable. Hasmi and Widyantoro worked over this period to promote more positive, practical approaches, using a more non-judgemental approach and concentrating on the health issues of sexuality and adolescence, but this was not always easy.

An example of the problem is to do with what is said about masturbation in different publications (Box 1) . The question of whether masturbation is dangerous is one of the most common subjects that arises in training sessions, a matter which many adults in the community have strong views on. None of the manuals quoted states that masturbation is normal, pleasurable or widely practised. Such statements might be found in sexual health guides in the west, but they could not be placed in an Indonesian government-sponsored publication.

The content of these manuals is relatively heavy on biology, disease, domestic violence and psychotropic drugs–all of which are regarded as priority problems. Aside from instilling some knowledge and substantial fear into young people, this approach offers little incentive for adolescents to read the material. The most attractive aspect of the first edition of the Indonesian AIDS Foundation manual was the amusing and sometimes quite explicit cartoon illustrations, but a few complaints from the field led the team to revise the content in later printings. There is now less explicit visualisation of sexuality, and more detailed illustration of illegal drug use.

Despite the extent of material, however, each youth centre and group we visited said they would like more material and more detail on issues of interest to young people. Peer educators argued that the teenagers they assisted had absorbed the biology lessons and warnings and wanted to know more about how to deal with sexual relationships, feelings and the practical challenges of unwanted pregnancy and STDs. In both large and small communities in Java, peer educators carried slick, expensive youth magazines from Jakarta or Surabaya, and from the content of their jokes and comments, they were rapidly absorbing the content: ten ways to find/please/understand/drop a lover, secrets of the film stars, a range of gynaecological issues.

The materials produced by governmental agencies seem to have had a minor impact in comparison to youth magazines, newspapers, television and radio progammes. Nonetheless, while the information marketplace may be very heterogeneous, youth leaders are keenly aware of the differences in veracity of different publications. Though adolescents love to read about the love life of film stars, they also believed that the materials produced for the peer educators and peer counsellors were more authoritative and had high expectations of their veracity. For this reason alone, content matters.

Services for adolescents

While many peer educators have expressed great enthusiasm for the adolescent educational programmes suggested by BKKBN, they have very little to say publicly about unmarried people's need for contraceptives, STD or other clinical services. Within BKKBN itself this is a matter of sensitivity, and in political spheres it is a virtual no-go area. There are few advocates for services, and no appetite for debate. Hence, almost without exception, young people motivated enough to seek out services rely on private pharmacies and doctors, or the occasional public clinic with a discrete activist doctor.

There are good reasons for thinking that this situation may be changing, however. Demographic trends are inexorably pressing for a rethink. As the age at marriage rises and young women's involvement in education and the workplace expands, the average Indonesian woman is spending more years single just at the time when her hormones and society's cultural messages are stressing the potential pleasures of romance and sex. The tensions of these trends produce unplanned pregnancies and premature weddings, as well as a demand for abortions, and the inherent gender inequity in these outcomes. The next step at the local level might logically be for greater calls for contraceptive services for sexually active young people.

While BKKBN might need to look at this issue, the pressure will fall most heavily on the Ministry of Health, which is responsible for all government family planning clinics, and the Ministry of Education, where regulations expelling pregnant students are already a matter of debate. While it is possible that local governments could take initiatives to provide services to young people, so far it is more common for local leaders to block any such requests from young people or medical personnel.

Local moralities vs. global realities

In contrast to the pronouncements of religious leaders calling for abstinence and piety, youth in Indonesia ask about the nature of things as well as issues of propriety and morality. It is partially the strength of their curiosity and their burgeoning sexuality that makes the adults so nervous. Any activity seeking to address adolescents and sexuality must necessarily confront local moralities. Programmes in the districts we visited were all prepared to deal with challenges from social conservatives. The consensus among local officials and trainers was that it was not effective to directly debate religious teachers, but rather to stress the positive elements they wanted to promote.

One example of this was a manual with illustrations of the body and sexual parts. A headmaster who had not been consulted about the programme raised strenuous objections to what he regarded as pornographic illustrations. A revised version of the book was prepared with the illustrations modified to make them less provocative. By that time discussions with the headmaster had overcome the original objection about the lack of respect for his authority in the school. The peer educator should have approached him first, to ask permission to meet his students. Elsewhere, the original book was still in use and no problems were reported with the illustrations. The concerns of parents and religious leaders diminished, and in many cases they became supportive and insisted that children pay close attention to lessons. One senior religious leader said that the main thing was to explain the text and illustrations in religious language to ensure that religious concerns were acknowledged.

Effectiveness and sustainability of this approach

Centralised planning and donor competition have fostered the development of pilot projects as a mainstay of development investment, including for adolescent reproductive health projects. All the activities, training, manuals and monitoring are designed to the scale of the pilot, with little consideration of the costs and difficulties of going to scale to the national level. When we came to review the peer educator initiatives of this World Bank-funded project, we were faced with prickly questions of effectiveness and sustainability from the national rather than the project point of view.

In addition, the decision to radically decentralise government responsibilities to the district level in 2001 has created the need to reconsider the roles of partner institutions and strategies. Central government is changing from direct management of national programmes to the promotion of national standards and initiatives. Local government will increasingly play a key role in the design and management of adolescent reproductive health programmes. Caught up in the euphoria of radical change, they may abandon or modify everything developed to date. Already central government offices are encountering difficulties obtaining data from former branch offices that are now managed entirely by local administrators, affecting data collection, investments and standards. Central authorities need to develop new visions of how they can facilitate innovation locally, and local governments have to find ways to raise finances for priority activities. All levels will need to cooperate to ensure that programmes are effective.

One of the barriers to cooperation is the lack of a common perception of the nature and magnitude of problems. Statistics relevant to adolescent reproductive health are rare and sometimes inaccurate, and even when accurate they are often misunderstood. More and better statistical information is needed.

With 42 million Indonesian adolescents needing information, it is not possible for central government authorities to produce enough authoritative manuals to satisfy demand. Thus new strategies are required for producing information in the public domain, e.g. in the media. Such information should reflect the multi-cultural, multi-religious nature of Indonesian society, and should take a non-judgemental (though not necessarily value-free) tone. One way to make such materials widely accessible is to indicate that there is an open, public domain copyright. Printers, publishers, local governments and schools could reproduce the material if the content is not modified. Central government and NGOs could also prepare timely materials on adolescent reproductive health to be released to magazines, newspapers and other media locally and nationally. Such material needs to be factual and refer to authoritative sources to discuss subjects like wet dreams, circumcision, masturbation, relationships, infectious diseases and sexual pleasure. Over time, it might be possible for accurate information to displace some of the nonsense that is common in publications for youth.

Television is increasingly the medium of influence across the nation. There are a remarkable number of “talking heads” programmes, with only a small amount of reproductive health and adolescent-oriented material. Most people contacted by the evaluation team mentioned their reliance on TV for information, and some expressed interest in natural science-type programmes. Radio talk-back and question-and-answer formats were also said to be popular in some districts. While cost is a serious issue in TV and radio programming, the advantages of national outreach, potential for repeat broadcasting and utilisation of local talent all suggest it might be useful for central government to consider underwriting programmes.

The pilot peer educator or mentor approach described in this paper involved a design and commitment of staff that would probably be beyond the capacity of most districts in Indonesia, particularly without support from local legislators. Nonetheless, it showed that there was great enthusiasm across a variety of communities for efforts to educate young people on ways to protect their reproductive health. We met hundreds of parents, students, religious leaders and officials who seemed to have a patent interest in the topic, and there is no reason to think that they are not typical of the nation. The challenge is to mobilise them in the cause of better adolescent reproductive health.

Acknowledgements

Thanks are due to the staff and participants in the peer education project of the Safe Motherhood Partnerships and Family Approach Project in Central and East Java, visited by Hull and the review team. Thanks also to Suprapto of BKKBN, who facilitated the visit and contributed substantially to our understanding of the project aims and outcomes.

Notes

* Brebes, Cilacap, Pemalang, Jepara and Rembang in Central Java, and Ngawi, Jombang, Trenggalek, Sampang and Pamekasan in East Java.

† The trainers included medical doctors and psychologists from Jakarta, local doctors with a background in adolescent issues and senior officials from BKKBN.

* Obviously, materials printed for a national audience cannot list addresses for all the youth-friendly health clinics and doctors in the country. However they could usefully describe the types of services that should be sought, and leave space on the cover of the publication for local clinics to stamp their contact details, or include local inserts.

References

- BKKBN. Memahami Dunia Remaja: Buku Bacaan Orang Tua. Understanding the World of Adolescents: A Reader for Parents. 2001; BKKBN: Jakarta.

- Edi Hasmi. Remaja Memahami Dirinya:Buku Bacaan Remaja Adolescents Understand Themselves: A Reader for Adolescents. 2001; BKKBN: Jakarta.

- N Widyantoro, W Sarsanto, DJM Sarwono. Kesehatan Reproduksi Remaja Adolescent Reproductive Health. 2002; BKKBN: Jakarta.

- BKKBN. Orang Tua Sebagai Sahabat Remaja When Parents are Friends. 2002; BKKBN: Jakarta.

- MS Drg. Sonti. Remaja dan Permasalahannya: Bacaan siswa SLTP, SMU dan SMK Adolescents and their Problems: Readings for High School Students. 2000; Department of National Education: Jakarta.