Abstract

Nicaragua’s Penal Code permits “therapeutic abortion” without defining the circumstances that warrant it. In the absence of a legally clear definition, therapeutic abortion is variously considered legal only to save the woman’s life or also to protect the health of the woman, and in cases of fetal malformation and rape. This paper presents a study of the theory and practice of therapeutic abortion in Nicaragua within this ambiguous legal framework. Through case studies, a review of records and a confidential enquiry into maternal deaths, it shows how ambiguity in the law leads to inconsistent access to legal abortions. Providers based decisions on whether to do an abortion on women’s contraceptive behaviour, length of pregnancy, compliance with medical advice, assessment of women’s credibility and other criteria tangential to protecting women’s health. The Nicaraguan Society of Obstetrics and Gynecology aimed to clarify the law by developing a consensus among its members on the definition and indications for therapeutic abortion. If the law designates doctors as the gatekeepers to legal abortion, safeguards are needed to ensure that their decisions are based on those indications, and are consistent and objective. In all cases, women should be the ultimate arbiters of decisions about their reproductive lives, to guarantee their human right to life and health.

Résumé

Le Code pénal du Nicaragua autorise les « avortements thérapeutiques » sans en définir les circonstances. L’avortement thérapeutique donne donc lieuàdes interprétations diverses : il est parfois considéré légal uniquement pour sauver la vie de la femme ou bien pour protéger sa santé, et en cas de malformation fætale ou de viol. Cet article étudie la théorie et la pratique de l’avortement thérapeutique dans ce cadre juridique ambigu. Avec des études de cas, un examen des dossiers médicaux et une enquÁte confidentielle sur les décès maternels, il montre comment cette ambiguété débouche sur une inégalité d’accèsàl’avortement légal. Les prestataires fondent leur décision de pratiquer ou non un avortement sur le comportement contraceptif de la femme, la durée de la grossesse, le respect des conseils médicaux, l’évaluation de la crédibilité de la femme et d’autres critères indirectement liésàla protection de la santé de la femme. La Société nicaraguayenne de gynécologie et d’obstétrique souhaite clarifier la loi avec un consensus de ses membres sur la définition et les indications de l’avortement thérapeutique. Si la loi charge les médecins de contrÁler l’accèsàl’avortement légal, elle devra établir des garanties pour que leurs décisions se fondent sur ces indications, soient cohérentes et objectives. Dans tous les cas, la décision finale appartient aux femmes, afin de protéger leur droitàla vie etàla santé.

Resumen

El Código Penal de Nicaragua permite el "aborto terapéutico" sin definir las circunstancias que lo justifican. A falta de una definición jurádica clara, al aborto terapéutico se le considera legal solamente para salvar la vida o proteger la salud de la mujer, y en los casos de malformación congénita y violación. En este artáculo se expone un estudio de la teoráa y práctica del aborto terapéutico en Nicaragua dentro de este marco judicial ambiguo. Mediante estudios de casos, una revisión de los registros y una investigación confidencial de las muertes maternas, se muestra cómo la ambigÁedad en la ley propicia acceso inconstante a los servicios de interrupción legal del embarazo (ILE). Los profesionales de la salud deciden la práctica de un aborto conforme al comportamiento anticonceptivo de la mujer, la edad gestacional, el cumplimiento de la asesoráa médica, la evaluación de la credibilidad de la mujer y otros criterios tangenciales a la protección de su salud. La Sociedad Nicarag ense de Ginecologáa y Obstetricia procuró aclarar la ley al fomentar un consenso entre sus miembros respecto a la definición y las indicaciones del aborto terapéutico. Si la ley designa a los médicos como los guardianes de la ILE, se deben tomar medidas preventivas para garantizar que sus decisiones se basen en esas indicaciones y sean consecuentes y objetivas. En todos los casos, la mujer debe ser el árbitro definitivo de las decisiones sobre su vida reproductiva a fin de garantizar su derecho a la vida y la salud.

It seems incomprehensible that a health care provider might refuse to perform a lawful medical procedure that is necessary to protect a woman’s health. However, that is precisely what may happen when the procedure, induced abortion, is highly stigmatised and providers are unclear as to what is lawful.

In countries where abortion is criminalised, exceptions in the Penal Code often permit legal abortion for medical or “therapeutic” reasons. Most Penal Codes also establish broad general indications for therapeutic abortion which can include to save the woman’s life or protect her health, in cases of pregnancy due to rape, and in cases of fetal malformation. The Penal Codes in most Latin American countries, for example, permit abortion to save the woman’s life, and seven countriesFootnote* permit abortion to protect the woman’s health.Citation3 These laws usually require that one or more physicians determine the eligibility of the woman for the procedure, but often do not provide further guidelines as to the criteria for making their decision. In Nicaragua the law offers neither general indications nor criteria.

There is clinical evidence that pregnancy can exacerbate many chronic health problems and traumatic events. Medical textbooks often list the physical, mental and social conditions that can put the health or life of a pregnant woman at risk. However, there is no international consensus on a list of morbidities for which pregnancy termination is the most judicious course of action,Citation1 and there are some health conditions where the risk of complications from pregnancy or fetal malformation is uncertain.Citation2

As a result, access to therapeutic abortion often depends on the personal judgement of individual doctors, who lack guidance as to the legal, health and ethical issues they must consider. When the law is ambiguous, health professionals may feel reluctant to provide legal abortion services.Citation4 For example, they may feel ethically obliged to weigh the health risks for the woman against those of the fetus, and may be influenced by moral, societal or religious views on abortion. This pressure has grave implications for women’s reproductive health and rights.

This paper presents a study of the theory and practice of therapeutic abortion in Nicaragua within an ambiguous legal framework, and documents the process by which the Nicaraguan Society of Obstetrics and Gynecology sought to clarify the law by developing a consensus among its members on the definition and indications for therapeutic abortion.

Ambiguity in the abortion law in Nicaragua

Abortion is currently legal in Nicaragua only when it is “therapeutic”, which must be determined scientifically by at least three physicians and performed with the consent of the spouse or closest relative of the woman.Citation5 Footnote* Unlike other countries’ laws, Nicaraguan law neither defines “therapeutic abortion” nor provides guidelines for the physicians controlling women’s access to it. Because the Penal Code contains no definition, Nicaragua’s Ministry of Health (MINSA) is the public institution responsible for specifying the conditions under which legal abortionsFootnote† can be performed and for regulating service delivery. The MINSA had no official policy on legal abortion procedures until 1989 when norms for abortion services were published by the outgoing Sandinista government.Citation6 Officials in the conservative administration replacing them considered the norms impractical and ill-considered. As a result, they were never widely disseminated or implemented, and effectively disappeared.Citation7 The MINSA has not put forward any official policy on legal abortion since then.Citation8

Public debate on abortion became intense in 2000—01 as a result of proposed reforms to the Penal Code.Citation9 Battle-lines were drawn as conservative groups proposed eliminating therapeutic abortion from the Penal Code, and women’s rights activists and obstetrician—gynaecologists joined to defend it. During the debate, “therapeutic abortion” was considered by some opinion leaders to be legal only to save the woman’s life while others also included protecting the physical and mental health of the woman, and in cases of fetal malformation and rape.Citation10, Citation11

The case of nine-year-old “Rosa” highlights contradictions

The ambiguity of the law captured international attention in February 2003 when a nine-year-old Nicaraguan girl, “Rosa”, was discovered to be pregnant as a result of rape. Although Costa Rican law permits abortion to protect a woman’s health,Citation12 Footnote** the doctors who saw the girl in Costa Rica, where she was living with her parents at the time, denied that the pregnancy would endanger her physical or mental health and refused to consider an abortion.Citation13, Citation14 Aided by women’s rights activists, Rosa and her family returned to Nicaragua and requested a therapeutic abortion. The committee of doctors who examined Rosa in Nicaragua declared that continuing the pregnancy and terminating it presented an equal risk to her life, leaving it up to the parents to decide what to do.Citation15 Footnote* Rosa had an abortion without complications, but the legality of the abortion was questioned and an official investigation was opened to determine whether the doctors had violated the law. Finally, the Government officially declared the doctors innocent of any wrongdoing, given that therapeutic abortion was permitted.Citation16

The contradictory “scientific” assessments of Rosa’s health risks by the doctors in Costa Rica and Nicaragua reflect the powerful influences at work, and illustrate how a vague law can expose women and girls who seek abortion to ideologically-driven information and clinical care. The Nicaraguan committee avoided endorsing the abortion because of the enormous political pressures and media attention they faced. In effect, by leaving it up to the family to decide, they surrendered their authority to the courts.

Supporters of women’s rights in Nicaragua view the imprecise language of the law as both a challenge and an opportunity. On the one hand, abortion law reform advocates are afraid to call for the development of regulations for therapeutic abortion because it might result in counter-initiatives to eliminate therapeutic abortion from the Penal Code altogether. On the other hand, because therapeutic abortion has multiple definitions in both the legal and medical literature, progressive regulations could broaden the legal indications on health-related grounds and increase women’s access to services. Guidelines that would oblige physicians to consider the woman’s total well-being, both present and future, would find support in current textbooks on obstetrics and gynaecology,Citation17 the World Health Organization’s (WHO) definition of healthCitation18 and the WHO technical and policy guidance on safe abortion of 2003.Citation19 For abortion rights advocates, establishing clear regulations would be a giant leap forward without having to reform the law. For groups who oppose abortion, this represents the slippery slope they have been warning legislators about for years.

Methodology and participants

In late 2002 Ipas Central America and the Nicaraguan Society of Obstetrics and Gynecology undertook a collaborative project to clarify the definition and indications for therapeutic abortion, in order to develop a proposal to regulate services to present to the Ministry of Health. The project had four major components.

First, we reviewed the legal and clinical definitions of therapeutic abortion in the literature, conducted with the help of the website manager of Harvard’s population law database on abortion, including the Popline and Medline databases, obstetrics—gynaecology textbooks and scientific journals for operational definitions, case—fatality rates of morbidity exacerbated by pregnancy, and clinical criteria used for therapeutic abortion around the world.

We then obtained permission from the Hospital Bertha Calderón Roque, Nicaragua’s national maternity hospital, to review their therapeutic abortion decisions, in order to assess the extent to which scientific criteria were brought to bear. We reviewed all 115 requests for therapeutic abortions in the period from 1990 to 2003 and the official records of the proceedings.Citation20 Footnote† For each case, we analysed the factors that led to approval or rejection of requests. We also conducted several interviews with doctors who participated in the committees reviewing requests at the Maternity Hospital.

In addition, we obtained permission to review Ministry of Health records on the number of the legal abortions registered nationwide in 2001—02Citation21 and maternal death registers for 2000—02.Citation22 Nicaraguan records include pathologies present prior to pregnancy as well as those known to be aggravated by pregnancy, which helped to estimate the impact of women’s lack of access to therapeutic abortion. With their consent, we also conducted interviews with the families of three pregnant women who had died from causes that might have qualified them for a therapeutic abortion.

Lastly, we conducted a participatory consultation with Nicaraguan obstetrician—gynecologists to generate consensus on a definition and general indications for therapeutic abortion. This consultation was the second stage in developing proposed regulations on therapeutic abortion services for the consideration of the Ministry of Health. A previous survey had shown that 95% of the members of the Nicaraguan Society of Obstetrics and Gynecology believe that therapeutic abortion should be legal and 98% that the Society should be the principal expert group consulted on the medical and technical issues related to the regulation of abortion.Citation9, Citation23

We adapted the nominal group technique, a qualitative research method used to gather information from relative experts,Citation24 to reach a consensus on the general indications for therapeutic abortion. Project staff facilitated 15 small group discussions of 3—20 participants each, in different parts of Nicaragua, which focused on the general indications for therapeutic abortion. First, participants reviewed relevant literature and wrote down their individual definitions of therapeutic abortion on notecards, which they gave the facilitator. The facilitator grouped the definitions according to which indications they included. Indications included by at least 75% of participants were considered to be consensus indications. Participants were then asked to discuss any remaining indications. If, at the end of discussion, less than 75% of the group were in agreement with the indication, then the indication was excluded from the consensus definition of that group.

Each small group session reached consensus on a single definition of therapeutic abortion and its general indications. Representatives from each group were elected to attend a final session in which a weighted voting process was used to select the final definition. Two rounds of voting were conducted. First, each participant was given a list of the 15 definitions and asked to choose the three that best reflected their own group’s consensus, and to assign points to them for first, second and third place. The three definitions with the most points were the subject of a second round of voting. Finally, the group was asked to consider whether or not the regulations should include a list of specific indications for which therapeutic abortion should be considered legal.

Global jurisprudence on therapeutic abortion

At least eight countries have used the term “therapeutic abortion” historically in legislation on abortion: France, Germany, Spain, Canada, USA (California), Honduras, Guatemala and Nicaragua. These laws variously define(d) therapeutic abortion to include any or all of the following indications:

| • | to save the woman’s life | ||||

| • | to protect the woman’s health, physical and mental | ||||

| • | in cases of fetal malformation | ||||

| • | in cases of rape or incest. | ||||

Most other countries allow abortion for certain medical or therapeutic indications, but do not refer to them as therapeutic abortion. Until it was further restricted in 1985, Honduran law allowed therapeutic abortion to protect the woman’s health and in cases of fetal malformation and rape.Citation25 Guatemalan law permits therapeutic abortion only to save the woman’s life.Citation26 Nicaragua’s is the only law that permits therapeutic abortion without defining the indications that warrant it.

In the 1950s the American College of Gynecology and Obstetrics developed guidelines and indications for therapeutic abortion that included all four of the indications above and specifically mention physical and mental health.Citation27 Many leading textbooks of obstetrics and gynaecology have adopted this definition.Citation17 The medical establishment has acknowledged, however, that the decision to terminate pregnancy for maternal health indications may involve a subjective assessment of health risk.Citation1, Citation2, Citation27

Therapeutic abortion decisions 1990—2003 in the national maternity hospital

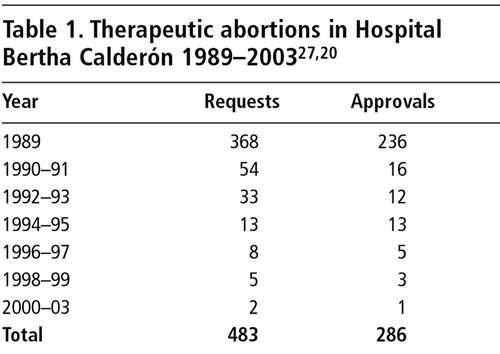

Studies based on data from Nicaragua’s largest maternity hospital, Hospital Bertha Calderón Roque, which serves as the referral hospital for all obstetric and gynaecology-related complications nationwide, indicate a dramatic drop in registered therapeutic abortion requests after 1989 ( ). Whereas 368 requests were recorded in 1989, there were only 54 in 1991—92 and only two after 1999.Citation7 This decline coincided with the election of Violeta Chamorro and a conservative government. Nationwide, only six legal abortions were recorded by the MINSA in 2001 and again in 2002.Citation21

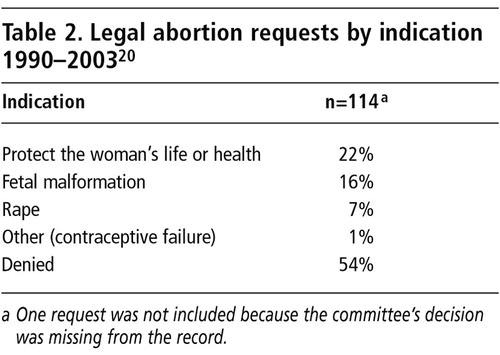

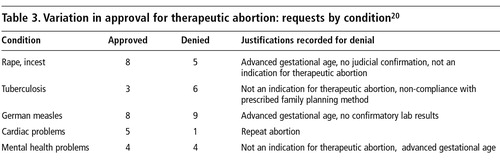

The records included data on the patient’s medical history and explanatory notes about the decision of the members of the evaluation committee. Of the 115 requests, 52 (45%) were approved by the committee for the indications shown in . Doctors denied requests from women with confirmed diagnoses of pre-eclampsia, hepatitis, diabetes, colon cancer, alcohol addiction, mitral valve prolapse, measles and mental retardation. The responses to requests were not consistently based on pathology. Some requests from women with tuberculosis, German measles, pregnancies due to rape, mental health and cardiac pathologies were approved, while others were denied ( ).

There were several inconsistencies in the records. In one case, a woman with a serious cardiac condition was approved and underwent a therapeutic abortion. The same woman returned several years later, having become pregnant again, and was refused due to “repeat abortion”. Non-compliance with medical advice was also a rationale for denial of termination in other cases too. In one case, the record noted that the woman was provided with counselling and a contraceptive method when she was being treated for tuberculosis, but did not use it.

Three records cited the lack of “judicial confirmation” as a reason for refusing requests when pregnancy was due to rape. Doctors even used this justification in the case of a 13-year-old girl, even though in Nicaraguan law, sexual intercourse with minors under the age of 14 is considered statutory rape.Citation28 Nor does Nicaraguan law ask for judicial confirmation of rape as a prerequisite to legal abortion. In fact, the WHO guidance discourages such requirements.Citation19

Length of pregnancy and failure of contraceptive method were also taken into consideration by the committees. If a woman could demonstrate that she had been using a contraceptive method at the time she got pregnant, her request was more compelling to the committee. One of the approved requests was based on the failure of a displaced intrauterine device (IUD). The request was accompanied by a referral note from the health facility that had inserted it, acknowledging responsibility. All other requests based solely on contraceptive method failure were rejected, however.

With respect to length of pregnancy, there was one approval at 14 weeks of pregnancy for a health care worker exposed to radiation. However, six other requests by women 10—14 weeks pregnant were rejected on the spurious grounds of “advanced gestational age”.Footnote*

Maternal death registers and confidential inquiries 2000—02

Between 2000 and 2002 a total of 33 women died who had pre-existing health conditions that may have been exacerbated by pregnancy.Citation22 These women suffered from tuberculosis, leukaemia, renal and cardiac problems. It is impossible to determine from the medical records whether or not providers offered them a therapeutic abortion. Equally difficult to discern post-mortem is how many would have availed themselves of abortion had it been offered. However, in at least one case, the mother of the woman who had died thought it could have made a difference:

“…if I had known that it was possible for her to have an abortion, so that she wouldn’t have to risk her life, I would have requested it and demanded that they give it to her from the very start of her pregnancy. And I’m sure she would have too, because she wanted to keep on living for the child she already had.” (Interview, 19 May 2003)

A consensus definition for therapeutic abortion

A total of 159 obstetrician—gynaecologists participated in the process of defining therapeutic abortion, representing 73% of those licensed by the Ministry of Health in 2000. Forty-six per cent of survey respondents were women and 54% men; 47% were 40—60 years old and the rest under 40. The majority were public sector providers (64.2%). The high response rate may be attributable to the fact that Nicaraguan obstetrician—gynaecologists have witnessed the vagaries of the law and been exposed to accusations of misconduct that have compromised their ability to serve their patients, as in the Rosa case.

The definition that was generated through the participatory process was:

“Therapeutic abortion is defined as the termination of pregnancy when, according to the criteria of the physicians, at least one of the following conditions is present: (a) When the life or health of the woman is threatened; (b) when the continuation of pregnancy will result in the birth of a child with serious physical malformations or mental retardation; or (c) in the case of rape or incest.” Citation8

The 15 small group representatives were asked to consider whether the guidelines proposed should include a list of specific health conditions that would qualify for therapeutic abortion. Three options were discussed: having no list, an exclusive list or a list that would serve as a guide but would not be exclusive. After discussion, the recommendation was that each case should be considered individually, without a list of health conditions.Citation29 It was agreed that any such list might influence doctors to exclude cases even though the woman’s health or life was in fact at risk. This is consistent with WHO guidance.Citation19

The process of reaching a consensus in the 15 groups was very difficult. Participants had been asked to use academic literature and other scientific criteria as the basis for their deliberations; however personal values, moral and religious views permeated the discussions. Many doctors expressed discomfort with the role that the “wantedness”of a pregnancy might play in a woman’s motivation to seek a therapeutic abortion. Comments revealed an underlying preoccupation with women’s intentions and fears that maternal health risk could be used as a pretext for ending a low risk but unwanted pregnancy. Whether a pregnancy was wanted or not was perceived by participants to blur the distinction between therapeutic abortion for medical reasons and elective termination.

Although it was eventually included in the consensual definition, rape was the indication that prompted the most debate among the physicians. Central to the discussions was the question whether women can be trusted not to lie about being raped and whether or not rape needed to be confirmed by forensic experts. Despite WHO guidance advising against judicial requirements,Citation19 some doctors felt that forensic confirmation would shield them from litigation.

Participants also engaged in impassioned debates as to whether or not pregnancy due to trauma from rape or incest endangers women’s mental health.Citation29 Most of them were unfamiliar with the literature on the psychological sequelae of sexual violence and forced pregnancy.

Participants were supportive of the the Nicaraguan Society’s initiative to develop clear therapeutic abortion regulations, which they believed would also serve to protect providers against litigation and defamation if the need to provide a therapeutic abortion arose.

Discussion

Our findings exemplify the quandary health workers face in a legally restricted environment. Where the law makes doctors responsible for deciding whether or not pregnancy termination is therapeutic, their decisions rest precariously on their limited ability to predict health risk or diagnose rape.

The discussions among the physicians who contributed to the consensus definition, as well as the maternity hospital records, clearly show that doctors often considered factors tangential to health risks when considering a request for therapeutic abortion. Some may have felt compelled to scrutinise women’s motives to preclude challenges to their professional ethics. Others may have privileged fetal survival over maternal health in more advanced pregnancies. Others may simply be opposed to abortion more generally.

Given these subjective factors and the predictive limits of medical science, we are prompted to question the logic of thinking that science alone can drive the decision whether to grant a therapeutic abortion. Because the risk to health is often uncertain, only a woman’s informed judgement can be the determinant of the extent of the health risk with any pregnancy.Citation2

Furthermore, it is impossible to eliminate or separate out the role that wantedness or unwantedness of a pregnancy should play in a maternal risk assessment. The degree of risk that a woman will accept to bring a pregnancy to term is inextricably related to how wanted her pregnancy is. Attempts to separate them are futile and misguided.

Nicaragua’s abortion law keeps self-determination out of women’s reach by requiring that three or more physicians approve a request for legal, therapeutic abortion. Yet women bear the risks of pregnancy alone. It is both unfair and discriminatory to deny them a decisive voice in the clinical management of their own bodies.

Although this study exposes a stunning absence of women’s voices in their own self-determination, our findings may yet provide a key for expanding reproductive rights. For example, the fact that therapeutic abortions for women who have been raped have been approved in the past, e.g. in the “Rosa” case, confirms both de facto and de jure the right of all women to legal abortion of a pregnancy due to rape.

Our review indicates that the rulings on whether or not specific health conditions allowed therapeutic abortion were inconsistent. This raises serious doubts about the equity and credibility of putting the decision into the hands of a medical committee. As long as doctors remain gatekeepers, systems are needed to guarantee the consistency and objectivity of their decisions, and ensure the informed participation of women and respect for women’s human right to health, whatever the degree of risk. This obligation appears not to be fully understood by health providers in Nicaragua; training and guidelines would aid them in giving unbiased, evidence-based care.

We conclude that without a strong policy framework protecting women and providers, individual women’s access to legal abortion will remain unfairly restricted by the influence of political ideologies, ignorance of the law and provider-biased interpretation of the criteria for therapeutic abortion.

Currently, Nicaragua’s abortion law serves neither of the ethical principles it aims to uphold: beneficence or justice. Nor are all Nicaraguan women free to exercise a right to which the law entitles them. Our review leads us to conclude that women who might have benefited from a therapeutic abortion may well have died unnecessarily due to lack of access. By democratically and thoughtfully reaching a consensus on what constitutes therapeutic abortion, the Nicaraguan Society of Obstetrics and Gynecology has taken an important step in supporting women’s reproductive rights and indeed their survival.

Acknowledgements

A technical report of this research, McNaughton LH, Padilla K, Fuentes D. El aborto terapéutico: garantiza la salud de la mujer, is available from the Ipas Central America office. We thank Dr Diony Fuentes, Dr Ligia Altamirano and Dr Karen Padilla for their contributions to this project. Thanks also to Charlotte Hord Smith for her encouragement, advice and comments on this article. Translations of text and quotes from Spanish to English were by Heathe Luz McNaughton.

Notes

* Argentina, Bolivia, Costa Rica, Ecuador, Peru, Uruguay and ten of the 32 states in Mexico explicitly permit abortion to protect the woman’s health. Rape is specified as a legal indication in Brazil, Bolivia, Panama, Uruguay and Mexico.

* Arto. 164. “El aborto terapéutico será determinado cientáficamente, con la intervención de tres facultativos por lo menos y el consentimiento del cónyuge o pariente más cercano a la mujer, para los fines legales.”

† Given that Nicaraguan law permits only therapeutic abortion, when referring to services in Nicaragua we use the terms “legal abortion” and “therapeutic abortion” interchangeably.

** Arto. 121. “Aborto Impune. No es punible el aborto practicado con consentimiento de la mujer por un medico o por una obstétrica autorizada, cuando no hubiere sido posible la intervención del primero, si se ha hecho con el fin de evitar un peligro para la vida o la salud de la madre y este no ha podido ser evitado por otros medios.”Citation14

* Hospital Vélez Paás. “La niña corre riesgo potencial de sufrir daño severo e incluso la muerte en cualquiera de las dos alternativas [interrumpir o continuar con el embarazo].”Citation15

† These records are housed in the office of the sub-director of the Hospital Bertha Calderón Roque in an archive of the therapeutic abortion committees’ decisions (libro de actas) going back to the 1980s. This is the only hospital we know of that keeps records of committee decisions on abortion requests.

* A number of serious health problems, such as pre-eclampsia, have an abrupt onset mid-pregnancy, making length of pregnancy an inappropriate reason for refusing an abortion.Citation2

References

- N Aries. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the evolution of abortion policy, 1951—1973: the politics of science Journal of American Public Health Association. 93(11): 2003; 1810–1819.

- P Stubblefield. Induced abortion: indications, counseling and services. Zatuchni, Sciarra. Gynecology and Obstetrics. Vol.6: 1988; JB Lippencott: Philadelphia.

- Harvard University. Annual Review of Population Law. At: http://cyber.law.harvard.edu/population/. Accessed 10 January 2004

- Cook RJ. Understanding legal grounds for abortion. Presented at: World Congress of the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics. Santiago, 2—7 November 2003.

- Código Penal de la República de Nicaragua, Tátulo 1. Delitos contra las personas, Capátulo V. Aborto, Arto. 164. Aborto Terapéutico.

- Ministerio de Salud de Nicaragua. Norma de atención al aborto. Dirección de Atención Integral a la Salud de la Mujer, Niñez y Adolescencia. 1989.

- AM Pizarro. Atención Humanizada del Aborto y del Aborto Inseguro. 1997; Servicios Integrales de la Mujer: Nicaragua.

- HL McNaughton, K Padilla, D Fuentes. El aborto terapéutico: garantiza la salud de la mujer. 2003; Ipas Centroamérica: Managua.

- HL McNaughton, MM Blandón, L Altamirano. Should therapeutic abortion be legal in Nicaragua: the response of Nicaraguan obstetrician—gynaecologists Reproductive Health Matters. 10(19): 2002; 111–119.

- Comité Nicarag ense Pro Defensa de la Vida. El aborto terapéutico es un asesinato legalizado: carta abierta a los honorables diputados. La Prensa. 4 June 2000.

- Red de Mujeres por la Salud. Basta de manipulación y desinformación: Si a la vida, no mas muertes maternas. 18 May 2000. (Flyer).

- Murillo M, Rodráguez R. Buena salud fásica de niña embarazada. La Nación. 6 February 2003.

- Rodráguez M. Descartan hacer aborto a menor. La Nación. 5 February 2003.

- Código Penal de la República de Costa Rica, Sección II. Aborto, Arto. 121. Aborto Impune.

- Hospital Vélez Paás. Informe Cientáfico Técnico de la Comisión de Análisis del Caso “Rosa.” Sub-Dirección del Hospital. 18 February 2003.

- Ministerio Público de Nicaragua. Resolución sobre los hechos denunciados por la ciudadana Dora Jacqueline Roque Velazquez sobre el aborto practicado en “Rosa”. 3 March 2003. Departamento de Managua: New York.

- NF Cunningham, FG Gant, KG Leveno. Williams Obstetrics. 21st ed, 2001; McGraw-Hill Professional: New York, 855.

- World Health Organization. Preamble to the Constitution of the World Health Organization as adopted by the International Health Conference, New York, 19—22 June, 1946; signed on 22 July 1946 by the representatives of 61 states (Official Records of the World Health Organization, No.2, p.100) and entered into force on 7 April 1948.

- World Health Organization. Safe Abortion: Technical and Policy Guidance for Health Systems. 2003; WHO: Geneva.

- Hospital Bertha Calderón Roque. Libro de actas sobre la interrupción del embarazo (aborto terapéutico), 1990—2003. 2003; Dirección del Hospital: Managua.

- Ministerio de Salud de Nicaragua. Admisiones y egresos hospitalarios 2001—2002. 2003; Dirección general de sistemas de información: Managua.

- Ministerio de Salud de Nicaragua. Fichas de muerte materna, 2000—2002. 2003; Dirección del primer nivel de atención: Managua.

- Ipas, Sociedad Nicarag ense de Ginecologáa y Obstetricia. Jornada Nacional de Reflexión Cientáfica: El Aborto Terapéutico y la Práctica de la Gineco-Obstetricia, Informe Final. May 2001.

- C Pope, N Mays. Qualitative Research in Health Care. 2nd ed, 2000; BMJ Books: London.

- Código Penal de la República de Honduras. 2002. Capátulo II. Aborto. Arto.141. Aborto Terapéutico. (Eliminated by Legislative Decree 13—85, 13 February 1985.).

- Código Penal de Guatemala. Decreto No. 17—73 con todas sus reformas incluidas, Capátulo III. Del aborto, Arto.137. Aborto Terapéutico. 12 June 2002.

- NE Roche. Therapeutic Abortion. eMedicine. 13 March 2003. At: http://www.emedicine.com/med/topic3311.htm. Accessed 19 January 2004

- Código Penal de la República de Nicaragua. Tátulo I. Delitos contra las personas y su integridad fásica, psáquica, moral y social. Capátulo VIII, De la Violación y Otras Agresiones. Arto.195.

- Nicaraguan Society of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Ipas. Notes on the national consultation of obstetrician—gynecologists on the definition and general indications for therapeutic abortion. 2003; Ipas Central America: Managua(Unpublished)