Abstract

Discourse on abortion rights inevitably centres on the fetus, and is often framed around the dichotomy of “pro-life” vs. “pro-choice” positions. This dichotomy is not, however, the only framework to discuss abortion; concerns about the fetus have found varied expression in theological, legal and medical constructs. This article examines discourses on the fetus from the Philippines, Iran and the United States, to show how complex they can be. It examines laws punishing abortion compared to laws punishing the murder of children, and also looks at the effects of ultrasound, amniocentesis and stem cell research on anti-abortion discourse. Although the fetus figures prominently in much legal discourse, it actually figures less prominently in popular discourse, at least in the English and Philippine languages, where terms like “child” and “baby” are used far more often. Finally, the article highlights the need to examine the experiences and narratives of women who have had abortions, and the implications for public policies and advocacy. It is important to expose the way anti-abortion groups manipulate popular culture and women’s experience, driving home their messages through fear and guilt, and to show that pregnant women often decide on abortion in order to defend their family’s right to survive.

Résumé

Le discours sur le droitàl’avortement se centre inévitablement sur le fætus et s’inscrit souvent autour de la dichotomie des positions « pour » ou « contre » l’avortement. Cette dichotomie n’est cependant pas le seul cadre de discussion de l’avortement ; les préoccupations pour le fætus ont trouvé diverses expressions dans des argumentations théologiques, juridiques et médicales. Cet article étudie le discours sur le fætus aux Philippines, en Iran et aux Etats-Unis, pour montrer sa complexité. Il compare les lois qui sanctionnent l’avortement avec les lois punissant le meurtre d’enfants, et s’intéresse aussi aux conséquences sur le discours anti-avortement de l’échographie, l’amniocentèse et la recherche sur les cellules souches. Si le fætus figure au centre de beaucoup de textes juridiques, sa place est moindre dans le discours populaire, au moins en anglais et en philippin, où les termes « enfant » et « bébé » sont utilisés beaucoup plus fréquemment. Enfin, l’article souligne la nécessité d’examiner les expériences des femmes qui ont avorté, et les conséquences sur les politiques publiques et le plaidoyer. Il faut expliquer comment les groupes anti-avortement manipulent la culture populaire et l’expérience des femmes pour véhiculer leurs messages par la peur et la culpabilité, et montrer que les femmes décident souvent d’avorter pour défendre le droit de leur familleàsurvivre.

Resumen

La disertación sobre los derechos de aborto inevitablemente se centra en el feto y suele enmarcarse en torno a la dicotomáa “pro-vida” contra posiciones “pro-libre elección”. Sin embargo, esta dicotomáa no es el único marco para analizar el tema del aborto; las inquietudes respecto al feto han encontrado diversas expresiones en las estructuras teológicas, jurádicas y médicas. En este artáculo se examina la disertación sobre el feto en Filipinas, Irán y Estados Unidos, para mostrar cuán compleja puede ser. Se analizan las leyes que castigan el aborto comparado con las que castigan el asesinato de niños, y además se estudian los efectos de la ecografáa, amniocentesis e investigación en células madre en la disertación anti-aborto. Aunque el feto se destaca en gran parte de la disertación jurádica, en realidad no se menciona tan a menudo en la disertación popular, por lo menos en inglés y en filipino, donde términos como “niño” y “bebé” se utilizan con mayor frecuencia. Por último, el artáculo resalta la necesidad de examinar las experiencias y lo referido por las mujeres que han abortado, y las implicaciones para la gestoráa y defensa y las poláticas. Es importante exponer la forma en que los grupos anti-aborto manipulan la cultura popular y la experiencia de las mujeres, recalcando sus mensajes mediante el temor y la culpa, y mostrar que las mujeres embarazadas a menudo optan por interrumpir su embarazo a fin de defender el derecho de su familia a la supervivencia.

Much of the discourse in western countries around abortion rights, in the United States (US) in particular, has revolved around the dichotomy of “pro-life” and “pro-choice” positions. In this configuration, support for abortion rights is mainly equated with the idea that abortion is a woman’s right to choose, a right closely tied to their rights over their bodies. Anti-abortion groups, on the other hand, proclaim themselves as “pro-life” in an effort to project the other side as being “anti-life”, life here referring only to that of the fetus.

While this pro-life vs. pro-choice framework is an important one, there are other discoursesFootnote* around abortion rights, shaped by different social and historical circumstances. This article reviews the pro-life vs. pro-choice framework as developed in the US and compares it with other discourses and frameworks from the Philippines and Iran, to show how these have evolved and had an impact on abortion rights. The US was chosen because this is where the pro-life vs. pro-choice framework remains the strongest, even though as an argument it is fraying at the edges. It is important to look at how old frameworks are being questioned, even as they are re-appropriated through new labels such as “pro-choice conservatives”.Citation1

The Philippines was chosen because of its peculiar colonial history, having been under Spain from the 16th to the 19th century, during which Catholicism was introduced. Catholicism remains the professed religion of about 85% of the population and church leaders continue to wield tremendous political clout, especially in relation to issues of sexuality. Following the Spanish colonial period, the Philippines was occupied by the US from 1898 to 1946. American influence also remains strong in terms of political institutions and processes. In the area of sexuality, it is curious that the American Religious Right, mainly identified with evangelical Protestants, have found allies among Filipino Catholic conservatives. Their impact on the discourse and policies on abortion in the Philippines is also described in this article.

Iran is included to offer a counterpoint in relation to the interactions between the legal system and a powerful Islamic tradition in the framing of abortion discourses and the law on abortion. This provides a basis for comparison with the zeal of the Religious Right with regard to abortion in both the Philippines and the US.

Fetal rights, children’s rights

This article is based on a newspaper article I wrote for the Philippine Daily Inquirer.Citation1 It was inspired by the work of Iranian lawyer and human rights activist Shirin Ebadi, who received the 2003 Nobel Peace Prize for her efforts to reform her country’s laws. A large part of Ebadi’s activism has been to expose the contradictions in Iran’s family laws. Her work provides activists in many countries with an important model for analysing laws to deconstruct culture, to bring out its problematic aspects and propose alternatives.

Ebadi has examined laws to do with the fetus, which she then contrasts with those relating to children. In a 1997 article entitled “On the legal punishment for murdering one’s child”, Ebadi wrote: “If a man helps a woman have an abortion which would result in the death of the embryo, he will be sentenced to three to six months’ imprisonment; on the other hand, if that very same embryo is not killed and lives to become a 14-year-old boy or girl, and the father kills him or her intentionally, that brutal father will receive a less severe punishment” of blood money with discretionary punishment that can be as light as one lash of a whip.Citation2

If a woman causes an abortion in herself, she has to pay blood money but is not imprisoned, which Ebadi describes as a more compassionate attitude. The blood money to be paid depends on the stage of pregnancy:

| • | a fertilised sperm placed in the womb: 20 dinnars | ||||

| • | a fertilised egg which has blood: 40 dinnars | ||||

| • | an early embryo: 60 dinnars | ||||

| • | a fetus which has grown bones but not muscular tissue: 80 dinnars | ||||

| • | a fetus whose bone and muscular tissue has fully developed but lacks a soul: 100 dinnars | ||||

Ebadi does not explain how “ensoulment” is determined but apparently, if the fetus is considered to have acquired a soul, then the blood money to be paid is equivalent to that paid for an adult. As with adults, however, the embryo’s value is gender-based — female embryos, like adult women, only deserve half the blood money paid for males.

Thus, the laws of Iran give more protection to the embryo or fetus than to children already born.

In a 2002 forum on children’s rights, Ebadi is quoted as saying: “Under the penal code, if a girl of nine and a boy of fifteen commit a crime, they are punished as adults… If the same boy or girl participates in a children’s painting competition and wins, they would need to obtain their father’s permission to receive a passport for travel… At the same time, we see that the same boy or girl cannot participate in elections as a voter. On the other hand, a lady at the age of 40, who is, for example, a university professor and wants to marry for the first time, needs her father’s permission to do so.”Citation3

Such inequities in the law are certainly not limited to Iran. Similar inconsistencies can be found, for example, in the Philippines, around definitions and penalties for abortion and murder.

Articles 256 to 259 of the Philippine Penal CodeCitation4 have detailed provisions on penalties for abortion as severe as imprisonment from 12 to 20 years for someone who uses violence to induce an abortion in a woman.

Under Philippine law, Article 246 of the Penal Code provides that a person who kills his or her own child will be tried for parricide, which can be punished with life imprisonment. Yet Article 247 makes an exception if the death or physical injury is inflicted under “exceptional circumstances” with destierro Footnote* prescribed as punishment for a parent who kills a daughter (though not a son) if she is below the age of 18, living with her parents and is caught having sexual intercourse. The same lighter sentence applies if the parent kills the daughter’s “seducer” after catching them having intercourse.

The contradictions in such laws merely reflect social norms, the origins of which may have been obscured by time. For example, Iran’s graded penalties for abortion, depending on the stage of fetal development, are drawn from Islamic theological speculation about ensoulment, a discourse which finds parallels in Christian theology, and which date even further back to classical Greek philosophy. Thomas Aquinas and early Christian theologians took the Aristotelean view that a fetus first acquired a vegetable soul, followed by an animal soul and finally, a rational soul. Abortion before rational ensoulment was not considered murder. Christian theologians adopted the Aristotelean view that animation, somewhat akin to ensoulment, did not take place until 40 days after the conception of a male fetus and 80 days for a female fetus.Citation6, Citation7

The contrast between the elaborate legal protection of fetuses and the anaemic provisions for child murder highlight the powerful ideologies that govern social relations, particularly in terms of the authority of men over women. These ideologies are expressed more specifically in terms of the authority of the father over his children, especially daughters, and the need to protect female chastity and family honour, even at the cost of killing an erring daughter.

Given the heavy legal sanctions for abortion in relation to other laws, and especially in the absence of heavy punishment for murdering children, such abortion laws seem to be linked more to upholding male honour and authority over women and the family, rather than to the protection of the fetus itself.

From the fetus to the unborn

Although the fetus figures prominently in much legal discourse, it actually figures less prominently in popular discourse, at least in the English and Philippine languages. Terms like “child” and “baby” are used far more often, together with their emotion-laden connotations. Anti-abortion groups are aware of the power of these words so it should not be surprising that they pass out keychains with a fetus attached, sometimes given names such as Joshua. The message is clear: do you want to kill Joshua? To be pro-choice then is not just to be anti-life but in an even more terrifying sense, to be anti-baby and anti-child. This imagery is easily linked to other sensitive social issues, as shown in this excerpt from a posting on the Pro-Life Philippines website:

“The people who cry for more ”family reduction/culling/eliminate the 3rd, 4th and 5th child masquerading as planning’, more ”sex mis-education’, more ”I hate all men, I hate childbirth, I hate children’ feminism, are either in the business of selling contraceptives, misinformed, racist (they see the Filipino people as an inferior race), class oppressors (they see poor people as inferior and do not deserve to multiply), or blind followers of the dogma of overpopulation.” Citation8

Pro-Life Philippines links the imagery of the fetus to many other social issues, including that of women’s bodies. Members of Pro-Life Philippines regularly write to newspapers with dire warnings about the risks of cancer and other side effects from contraception itself. Such warnings are especially serious given that family planning surveys often show that the fear of contraceptive side effects tops the reasons for non-use and discontinuation of use.Citation9 Research that I and Health Action Information Network, a non-government organisation (NGO), have carried out in the Philippines on perceptions of contraception have consistently shown how strong these fears are, and that they are picked up from stories told by Catholic church workers.Citation10, Citation11

Not surprisingly, when mifepristone was approved as a medical abortion drug in the US, Philippine groups expressed their outrage through graphic references to the womb and the fetus. Francisco Tatad, a Philippine Senator, described the drug as “the equivalent of a miniature chemical bomb detonated inside a mother’s womb. It is guaranteed to kill the fetus instantly.”Citation12

Thus, anti-abortion rhetoric invokes not just the fetus but also the womb. Moreover, the Catholic anti-abortion movement, especially in the Philippines, goes further and lumps abortion and family planning together as being anti-family. In January 2003, the Philippines hosted a World Congress on Families, which allowed anti-abortion groups to maximise their own media exposure using imagery of fetuses, babies and children. In one striking example, the organisers of the congress announced that they were giving delegate status to 42 babies and toddlers, one as young as 10 months old. Manila’s Auxiliary Bishop Socrates Villegas described these children as “the secret powerhouse of the congress”, and said they were there “to dramatise the Church’s strong stance against abortion and artificial contraception”. He is also quoted as saying: “It takes a sick mind to get bothered by the sight of a baby. The normal mind gets excited and thrilled to see a baby because every baby is a blessing… There is no baby who enters the world from the womb of the mother as a curse.” This same bishop lamented that people sometimes “deposit aborted babies” at the EDSA Shrine, a church under his care.Citation13 Footnote*

The imagery of fetuses and babies is not confined to representations in the media, however. In several cities, Pro-Life Philippines has been able to convince local government officials to put up monuments to aborted fetuses. In front of the Quiapo church, in a central district in Manila, there is a “Shrine to the Unborn” showing a fetus on an outstretched palm with a crucifixion wound, presumably that of Jesus Christ. On Shaw Boulevard, a busy street in Metro Manila, there is a five-story building that on one wall facing the street has a painting of Jesus carrying what seems to be a fetus but could also be an infant. A caption under the mural reads: “This is a child, not a choice.”

One could argue that images are only images, and perhaps that they have little impact on people’s actual lives, but these larger-than-life representations are only part of a larger campaign by Pro-Life Philippines that has succeeded in adversely affecting policies on family planning by describing modern contraceptives as abortifacients.

In 1995, the Philippines devolved authority over health services and health policies to local government, opening up new possibilities for the Religious Right. The result has been disastrous for family planning. Whenever a pro-life city mayor or provincial governor comes to power, he (they have always been men) usually prohibits “artificial contraception” in local health units. Invariably, the argument, mainly put forward in TV interviews, is that the pill and other “artificial” methods are all abortifacients.

In another instance, Abay-Pamilya, an anti-abortion group affiliated to Pro-Life Philippines, was able to pressure the Health Department to withdraw Postinor, an emergency contraceptive pill. The move was made without public hearings and was based on the argument that the drug was an abortifacient. In reality, emergency contraception works within the first 72 hours after unprotected intercourse, a time when fertilisation may or may not have taken place. The anti-abortion groups argued that because there was a chance fertilisation had taken place, the drug would then work as an abortifacient. Health NGOs came forward demanding the return of emergency contraception, invoking the medical definition of pregnancy as starting at the time of implantation rather than fertilisation. The legal hearings, a debate on the status of the zygote and the embryo, have continued and are unlikely to be resolved in the near future.

Since 2002, still another term, “the unborn”, has come into wider usage, with Philippine President Arroyo declaring 25 March 2004 as the “Day of the Unborn”. The choice of date is tied to the Catholic feast of the Annunciation, when angels were said to have announced to the Virgin Mary that she was pregnant with Jesus. The President said the day was a way of promoting a “culture of defending life from the moment of conception”,Footnote† and was intended to focus attention on “babies that died during their mother’s pregnancy”, with a rather cryptic reference to the fact that “3% of fetal deaths recorded were due to ill-health of pregnant women and socio-behavioural factors”.Citation15

On the surface, this could be seen as concern for maternal health. But shortly after Arroyo declared the “Day of the Unborn”, Conrado Limcaoco, her advisor on ecclesiastical and media affairs (the combination of the two functions is itself revealing), told newspaper reporters that he had read about similar events in other countries on Zenit, a conservative Catholic media service. Limcaoco’s own rationale for the event was: “As the Philippines is the only Roman Catholic country in Asia, it is important that we make a clear stand for the dignity of life and the protection of the unborn who are unable to protect themselves.”Citation15 Footnote*

Not surprisingly, Arroyo’s “Day of the Unborn” has appeared on the Internet sites of anti-abortion groups, e.g. the Canadian Campaign Life Coalition hailed the declaration of the day as another example of defending the unborn.Citation16 Manila’s Mayor Jose Atienza, running for re-election, chose to start his campaign on that day, which he dubbed the “Day of the Unborn Child”. This mayor has been outspoken in his views against abortion and family planning. He has banned artificial contraception from all city health offices, and created a Haven for Angels, which he described in a BBC documentary, Sex and the Holy City, as containing “fetus babies we find in the streets, garbage…”.

The unborn have also taken centre stage in the US where, on 2 April 2004, President Bush signed the Unborn Victims of Violence Act. This new federal law prescribes that a person who inflicts violence on a pregnant woman and who then harms the mother and the fetus can be tried for two separate crimes, in effect giving the fetus legal status. With rhetoric similar to Arroyo’s, Bush gave the following rationale for the new law:

“With this action, we widen the circle of compassion and inclusion in our society, and we reaffirm that the United States of America is building a culture of life.” Citation17

Medicine, embryos and fetuses

The discourse of the womb and the fetus is not new, as seen in the specific Iranian penal provisions relating to the fetus and its stage of development. In recent years, advances in medical research, particularly in fetal and reproductive medicine as well as in biotechnology, have led to new and powerful imagery of the fetus.

The 9 June 2003 American edition of Newsweek had a cover showing a fetus. The cover story’s theme was “Should a fetus have rights? How science is changing the debate”. An article inside entitled “Treating the tiniest patients” described various medical procedures, including surgery, that can now be performed on fetuses. The article notes: “Twenty-five years ago scientists knew little about the molecular and genetic journey from embryo to full-term fetus. Today, thanks to the biomedical revolution, they are gaining vast new insights into development, even envisioning a day when gene therapy will fix defects in the womb.” Author Claudia Kalb believes that “medicine has already granted unborn babies a unique form of personhood — as patients”.Citation18 Kalb focuses on fetal surgery because she believes this raises the stakes around political, moral and ethical debates:

“The very same tools — amniocentesis and ultrasound — that have made it possible to diagnose deformities early enough to terminate a pregnancy are now helping doctors in their quest to save lives. While fetal surgery is still rare and experimental, the possibility that a fetus that might have died or been aborted ten years ago might now be saved strikes at the core of the abortion debate. And these operations also raise a fundamental question: whose life is more important — the mother’s or the child’s.” Citation18

It is not surprising that the bioethical debate around abortion is rapidly changing. As fetal surgery can be performed in the womb, and more premature babies are being kept alive, anti-abortionists argue that fetal viability is occurring earlier in pregnancy, and calling for a reduction in the number of weeks of pregnancy that abortion should be permitted. The US Supreme Court in fact recently handed down an opinion that states could prohibit abortion after viability, which was defined in that judgement at 24 weeks of pregnancy.Citation19 However, the scientific evidence is that up to 24 weeks the survival rate is below 10% and more than half of the few infants that survive show evidence of more or less severe physical problems and learning difficulties. It is only beyond 26 weeks that survival chances rapidly increase above 50% and the rate of handicap among survivors drops below 50%.Citation20

These debates have become even more heated in relation to stem-cell research, in which human embryos are being used to develop cell lines that can be used to treat diseases such as juvenile diabetes, Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s disease. US President Bush is vehemently opposed to such research and has banned the use of federal money for research on stem cell lines, an obviously political move which drew praise from groups such as Focus on the Family, whose president James Dobson hailed Bush as having “courageously upheld his promise to protect unborn children”.Citation21 The attempt to link unborn children and stem cells may seem overdone but it is only one example of how overarching themes from culture, medicine and politics come together to challenge advocates for abortion rights and, to borrow from Newsweek, the entire “politics of the womb”.

Kalb’s article on fetal rights in the US begins with the story of Tracy Marciniak, who five days before her expected delivery, was punched in the stomach by her estranged husband. When Marciniak had herself checked that night in a hospital, doctors could not detect any fetal heartbeat. Marciniak’s husband was eventually convicted of reckless injury and sentenced to 12 years in prison. He could not be charged with homicide because the existing laws apply only to “born persons”. Marciniak eventually became a key figure in the campaign to pass the Unborn Victims of Violence Act. The groups supporting the Unborn Victims of Violence Act have been mainly anti-abortion groups, yet Marciniak, at least until her husband’s assault, was a supporter of abortion rights.Citation18

Kalb also interviewed a couple, Pieter and Monica Coenradds, described as devout Catholics who are strongly opposed to abortion. Yet because one of their daughters was diagnosed with a debilitating neurological disorder called Rett syndrome, the Coenradds support embryonic stem-cell research, which they hope will yield therapy for their daughter’s illness. The Newsweek article summarises the paradox:

“When abortion foes are willing to destroy embryos for life-saving medical research and abortion rights supporters are willing to define a fetus as a murder victim, the black-and-white rhetoric of the 1970s’ abortion wars no longer applies.” Citation18

Moreover, use of the Internet is a particularly intriguing development, especially in the way it can draw information from the ancient past to help stimulate new perspectives to address present-day realities. For example, there is now a website called Answering Islam, with a whole section that analyses advances in reproductive medicine, particularly embryology, using interpretations from the Qu’ran, the Hadith (sayings attributed to Mohammed) and medical research.

Talking to the fetus

This article has centered on the discourse generated in medicine and law and the way terms are picked up, particularly by anti-abortion groups, to shape public opinion. People process these messages and images in different contexts. For example, Americans use both medical terminology (fetus, embryo) as well as popular terms like baby and child when talking about a pregnancy. There is a tension in these terms, affected by aspects of research in fetal medicine seeping into popular consciousness.

In the Philippines, the linguistic distinctions are different, reflecting a different epistemology regarding pregnancy. Fetus and embryo are terms familiar only to those who use English as a first language, who are a minority. In popular culture, a pregnancy is described quite differently. Dugo (blood) is used to refer to the fetus during the first few weeks of pregnancy. During this stage, medicinal plants as well as western pharmaceuticals such as misoprostol are described as pampabalik ng regal (restoring menstruation). This whole phase, too, is referred to as paglilihi, a protracted period of conceiving. After the first trimester of pregnancy, women will refer to the fetus as bata (child), anak (child) or sanggol (baby).

The use of these terms is not exactly the same as in the US or other societies, and this is why it is important to conduct research to understand the full context of the uses of these terms. To this end, Likhaan, a Filipino NGO involved in reproductive health care, recently released preliminary results from interviews with women who had had abortions.Citation22 They note widespread personification of the fetus, where women say they actually talk to their bata, anak or sanggol as they try to decide whether they will abort or not. The women’s stories are quite moving, as they try to explain to the fetus why they have to choose abortion. Striking in their stories is the way the fetuses are personified on one hand, but also often described as sagabal (obstacles). Another account, recorded in 1998 during a research project in the southern Philippines, was of a mother who described apologising to the fetus: “I’m sorry, but I have to do this so your brothers and sisters can live.”

A nationwide study conducted by the University of the Philippines Population InstituteCitation23 found that economic hardship was cited most often as the reason for abortion. Likhaan’s interviews showed that while economic factors were also the most important, there were other important reasons for abortion too: not being able to finish school, abandonment by the husband or partner, rape, domestic violence and, yes, pregnancies that are too many, too soon. The women’s stories show it is impossible to identify one reason for an abortion. An unmarried secondary school student will be driven to abort by a mixture of fear and shame. A battered wife talks about how she is beaten up, but finally explains it is the husband’s dependency on alcohol and drugs that makes her decide on the abortion, because he is unable to help support the family.

The decision to abort is not a moment in time. Women talk with other women, with their partners and with the embryo/fetus. They go to church as well, praying for a sign, to have or not to have the abortion. One woman claims she won P8000 (about US$200 at the time of the interview) in a lottery after praying for a sign, money which paid for her abortion.

Likhaan reports accounts of how hospital staff would harass women seeking help for abortion complications, including threats of legal action or worse. One woman in the Likhaan interviews described a woman physician who told her, when she was wheeled in bleeding: “You may still be alive, but your soul is now burning in hell.” If abortion is successful, the woman still has to prepare alibis to use upon her return to the community, since neighbours are often aware of a pregnancy. And long after the abortion, memories and stories will persist, including the many events that led to the abortion, and the times when women talked to the fetus, sometimes right after the abortion.

The paradox here is that while fetuses are personified in many cultures, there is a dearth of cultural mechanisms to deal with this personification of the fetus. A notable exception is Japan, where temples offer mizuko kuyo (memorial services for water babies), with women returning year after year offering incense and prayers for aborted, miscarried and stillborn fetuses. In sharp contrast, the Roman Catholic church, despite its strident anti-abortion stand, has no officially prescribed prayers or rituals for fetuses, whether aborted or miscarried. It should not be surprising that Likhaan’s research showed so much agonising in relation to unwanted pregnancies and the tortuous decision-making processes for an abortion.

Implications for advocacy: listening to women’s voices

Deconstructing the imagery around abortion, and understanding its social and historical context, are important for strengthening advocacy and reproductive health services. This is not to suggest that abortion rights groups ape the tactics of the anti-abortionists, exploiting popular images and associated emotions around fetuses and babies. Instead, advocacy efforts should draw on women’s own descriptions of their reproductive lives, their pregnancies and the circumstances and concerns that lead to a decision to have an abortion. Likhaan, for example, drawing on their interviews, produced a play called Aming Buhay (Our Lives). The play shows how abortion takes on different meanings and tensions for a young unmarried girl as compared to a middle-aged mother of five. The most powerful story is that of a young, unmarried, pregnant girl facing the fury of her father, who goes on about having lost their family’s honour. When the girl’s mother comes to her daughter’s defence, the father shifts his wrath to his wife, who had had an abortion many years before. “Anak ko ’yan” (“That was my child”), he bellows, dramatising the patriarchal construction of the fetus.

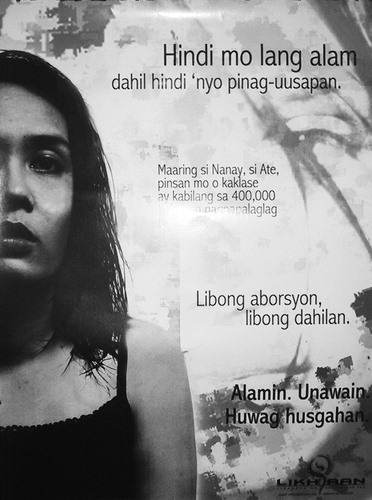

Likhaan has produced several posters that they hope will encourage a more open and less judgemental discussion of abortion. One poster reads: “It could be (your) mother, your older sister, a cousin or a classmate among the 400,000 women who have abortions each year.” In another part of the poster are the stark words: Libong aborsyon. Libong dahilan (Thousands of abortions. Thousands of reasons.)

Likhaan poster: ”You don’t know because it’s not talked about. It can be your mother, an elder sister, a cousin, a classmate… Thousands of abortions, thousands of reasons. Know. Understand. Don’t judge.’

Drawing on women’s experiences can and should include images of the fetus, recognising that in popular culture women do grapple with what the fetus means as part of what abortion means, and this helps to get around the pro-life vs. pro-choice dichotomy. Some feminists have in fact argued against the idea that the fetus is completely devoid of value, as this does not represent many women’s experience of unwanted pregnancy and that “fetal value can vary and increase as pregnancy progresses”.Citation24

Whether abortion is legal or not, discourse around this issue is pervasive, found in popular culture as well as in legal and medical texts. A focus on women’s experiences does not mean moving away from the politics of the womb. In fact, a focus on the fetus allows an interrogation of the so-called pro-life rhetoric, asking anti-contraception bishops and mayors if they have ever linked the aborted babies that end up in their garbage cans or their churches to their own prohibition of contraceptive use. The lack of access here includes the absence of contraceptive services, not only in cases where such services have been banned, but also social inaccessibility — the fear of contraception fanned by anti-abortion groups that prevents women from using it.

In places like the Philippines, where abortion is illegal, women tell horrendous stories about the pain from catheters inserted in the uterus, pain from massage by traditional birth attendants and harassment by hospital staff, and speak of feelings of fear, guilt and shame, and the consequent need for social support.Citation22 Anti-abortion groups distort these needs as post-abortion trauma. Thus, it is important to expose the way anti-abortion groups manipulate popular culture and women’s experience, driving home their messages through fear and guilt and showing how the invocation of terms like baby, child and unborn can be manipulative and callous, insensitive to the circumstances surrounding the need for abortion.

William Saletan, in his book Bearing Right, Citation25 points out that even the rhetoric of American pro-choice groups, with its emphasis on privacy and individual rights, has been effectively co-opted by anti-abortion groups, who now argue against abortion as excessive government interference in matters that should be kept private and within the family. This argument has been used, for example, to argue for parental notification before a minor’s abortion, and is an example of how concepts of confidentiality and privacy can be distorted to ends which are the opposite of what the concepts themselves stand for.

The article began by referring to the contradictions in the laws of Iran and the Philippines, and the way they seem to be skewed towards protection of the embryo and fetus while neglecting the rights and needs of living children and of women. This wider analysis of law and policy, and of the discourse surrounding abortion, must be developed further for an environment that will allow progressive abortion law reform to be created and the chances of achieving reproductive rights are to change for the better.

Acknowledgements

The core ideas for this article were first developed in an opinion-editorial column entitled “Fetal rights, children’s rights” in the Philippine Daily Inquirer, 16 December 2003.

Notes

* “Discourse” in this article refers not just to what is said or printed — what some researchers would call “text” — but also to the whole range of images that are created, invoked and evoked by different stakeholders in the increasingly complex debates around abortion. These images are found throughout popular culture, from folklore to advertising, as well as in more formal and codified forms, such as laws and public policies.

* Destierro (a Spanish term) is defined in Article 87 of the Penal Code as a form of banishment or exile. In effect, destierro is an exemption from punishment due to the enormous provocation considered to be involved.Citation5

* It is quite common for people to leave aborted fetuses at the shrine. I suspect this is done because it is as close to a Christian burial as they can get.

† This is an obvious reference to the Philippines 1987 ConstitutionCitation14 which states, in Section 12, Article II: “The State shall equally protect the life of the mother and the life of the unborn from conception.”

* In public debates on moral issues, ranging from abortion to nudity in movies, conservatives often claim the Philippines is the “only” Catholic or Christian country in Asia as a reason for the importance of it defending certain values. The claim is false. East Timor has a Catholic majority in its population, while many other Asian countries have large Christian populations, e.g. South Korea.

References

- ML Tan. Fetal rights, children’s rights Philippine Daily Inquirer. 16 December 2003 7.

- Ebadi S. The Legal Punishment for Murdering One’s Child. No date. At: www.Iranianchildren.org/articles.html. Accessed 1 December 2003.

- Conviction of children under the laws of 78 years ago is better than the current laws. At: www.Iranianchildren.org/ebadiconviction.html. Accessed 1 December 2003.

- W Nolledo. The Revised Penal Code of the Philippines with Related Laws. 1998; National Book Store: Mandaluyong City.

- Article 247, Revised Penal Code. At: www.abogadomo.com/lawprof_247.html. Accessed 12 April 2004.

- J Malenschein. Whose View of Life? Embryos, Cloning and Stem Cells. 2003; Harvard University Press: Cambridge MA.

- U Ranke-Heinemann. Eunuchs for the Kingdom of Heaven: Women, Sexuality, and the Catholic Church. 1990; Doubleday: New York.

- Religion of overpopulation and contraception exposed. In: Prolife Philippines. At: www.prolife.org.ph/article/archive/64. Accessed 5 April 2004.

- National Statistics Office. National Demographic and Health Survey 1998. Manila: National Statistics Office, Department of Health and Calverton MD: Macro International Inc, 1999.

- Health Action Information Network. Transcripts of interviews with family planning acceptors, 1997. (Unpublished).

- ML Tan. Good Medicines. 2001; Het Spinhuis, University of Amsterdam: Amsterdam.

- JL Javellana. Tatad asks DOH to ban abortion pill Philippine Daily Inquirer. 3 October 2000 3.

- AN Nocum. 42 babies “secret powerhouse of congress” Philippine Daily Inquirer. 23 January 2003 1.

- JN Nolledo. The Family Code of the Philippines Annotated. 1997; National Bookstore: Mandaluyong City.

- MT Torres, M Ager. President Arroyo declares March 25 as “Day of the Unborn” Manila Times. 26 March 2004.

- Philippine President declares March 25 Day of the Unborn. At: lifesite.net/ldn/2004/mar/04032507.html. Accessed 5 April 2004.

- A Goldstein. Bush signs Unborn Victims Act Washington Post. 2 April 2004 A04.

- C Kalb. Treating the tiniest patients Newsweek. 9 June 2003 48–51.

- B Steinbock. The pro-choice view: when can it feel pain? Newsweek. 9 June 2003 47.

- H Schneider. [Obstetrical considerations regarding marginal fetal viability of very early premature infants (in German)] Schweiz Rundsch Med Prax. 92(13): 2003; 585–589.(From Medline abstract.)

- Boehlert E. Fighting stem cells, not terror cells. At: www.salon.com/news/feature/2004/04/08/stem_cells. Accessed 9 April 2004.

- Likhaan. Ibat Ibang Mukha ng Aborsyon [Different faces of abortion]. Manila: Likhaan (Transcripts of interviews with eight women, unpublished).

- CM Raymundo, ZC Zablan, JV Cabigon. Unsafe Abortion in the Philippines: A Threat to Public Health. 2001; Demographic Research and Development Foundation: Quezon City.

- R Fletcher. National crisis, supranational opportunity: the Irish construction of abortion as a European service Reproductive Health Matters. 8(16): 2000; 35–44.

- W Saletan. Bearing Right: How Conservatives Won the Abortion War. 2003; University of California Press: Berkeley.