Abstract

Abortion is illegal in Thailand unless the woman’s health is at risk or pregnancy is due to rape. This study, carried out in 1999 in 787 government hospitals, examined the magnitude and profile of abortion in Thailand, using data collected prospectively through a review of 45,990 case records (of which 28.5% were classified as induced and 71.5% as spontaneous abortions) and face-to-face interviews with a sub-set of 1,854 women patients. The estimated induced abortion ratio was 19.5 per 1,000 live births. Almost half the induced abortions were in young women under 25 years of age, many of whom had little or no access to contraception. Socio-economic reasons accounted for 60.2% of abortions. Serious complications were observed in almost a third of cases, especially following abortions performed by non-health personnel. Government physicians’ current provision of induced abortion went beyond the provisions of the law in almost half of cases, most commonly for intrauterine death and for congenital anomalies. The paper proposes a framework for policy discussions of the grey areas of maternal and fetal indications leading to legal reform, in order to facilitate safe abortion. A recommendation to amend the abortion law has been proposed to the Ministry of Public Health and the Thai Medical Council.

Résumé

L’avortement est illégal en Thaélande, sauf si la santé de la mère est en danger ou si la grossesse résulte d’un viol. Cette étude, menée en 1999 dans 787 hÁpitaux publics, examinait la fréquence et les caractéristiques des avortements en Thaélande, en utilisant des données recueillies dans 45 990 dossiers (dont 28,5% classés comme avortements provoqués et 71,5% comme spontanés) et lors d’entretiens personnels avec un sous-ensemble de 1854 patientes. La proportion estimée d’avortements provoqués était de 19,5 pour 1000 naissances vivantes. Près de la moitié des avortements provoqués concernaient des jeunes femmes de moins de 25 ans, dont beaucoup ont un accès limitéàla contraception. Les raisons socio-économiques expliquaient 60,2% des avortements. Des complications graves avaient été observées dans près d’un tiers des cas, particulièrement après des avortements pratiqués par du personnel non sanitaire. Les prestations des médecins en matière d’avortement provoqué allaient au-delÁ des dispositions de la loi dans près de la moitié des cas, généralement pour décès intra-utérin et anomalies congénitales. L’article propose un cadre de discussion politique des domaines mal définis des indications maternelles et fætales qui pourrait conduireàune réforme juridique, afin de faciliter les avortements s rs. Le Ministère de la santé publique et le Conseil médical thaélandais ont recommandé d’amender la loi sur l’avortement.

Resumen

El aborto es ilegal en Tailandia a menos que la salud de la mujer esté en riesgo o que el embarazo sea producto de una violación. Este estudio, realizado en 1999 en 787 hospitales gubernamentales, examinó la magnitud y el perfil del aborto en Tailandia, usando datos recolectados eventualmente mediant una revisión de 45,990 registros de casos (de los cuales el 28.5% se clasificaron como abortos inducidos y el 71.5% como espontáneos) y entrevistas cara a cara con un subgrupo de 1,854 pacientes. El ándice estimado de abortos inducidos fue de 19.5 por cada 1,000 nacidos vivos, casi la mitad de éstos en mujeres jóvenes menores de 25 años, la mayoráa con poco o ningún acceso a los anticonceptivos. El 60.2% de los abortos se atribuyó a motivos socioeconómicos. Se observaron complicaciones graves en casi la tercera parte de los casos, particularmente después de aquellos abortos practicados por personal ajeno a la salud. La práctica actual de los médicos estatales del aborto inducido fue más allá de las disposiciones de la ley en casi la mitad de los casos, siendo las más usuales la muerte intrauterina y las anomaláas congénitas. Este artáculo propone un marco para la revisión de poláticas relacionadas con la zona gris de las indicaciones maternas y fetales que llevan a la reforma judicial, a fin de facilitar el aborto seguro. Se recomienda al Ministerio de Salud Pública y al Consejo Médico de Tailandia enmendar la ley de aborto.

Induced, unsafe abortion is a major public health problem affecting the quality of life of women of reproductive age. This issue was given special consideration at the International Conference on Population and Development held in Cairo in 1994. Obtaining accurate data where abortion remains illegal is difficult. Very often, abortion rates are derived by means of estimates. Global estimates of 19 million unsafe abortions and 68,000 deaths annually were made for 2000, and unsafe abortions accounted for 13% of all maternal deaths.Citation1

Unwanted pregnancy and induced abortion in Thailand

Though Thailand has a good record in family planning (total fertility rate 1.9 and contraceptive prevalence rate 72% in 2000), unmarried women still have difficulties accessing family planning services, and unsafe abortions and complications are still major public health problems.Citation2

Routine hospital-based reports provide only the tip of the iceberg as regards abortion rates.Citation3, Citation4 Most women do not admit to induced abortion due to its illegal status and social sanctions. A one-year prospective observational study in 1984 found that 78% of abortions were induced, 13% therapeutic and 65% illegal, and 22% were spontaneous. Among the unmarried women who had had therapeutic abortions, the main reasons were in fact socio-economic, e.g. pre-marital pregnancy, student status and against some occupations. Among the married women who had therapeutic abortions, the main reasons were socio-economic and contraceptive failure.Citation5

Legal perspectives: problems arising from the Thai abortion law

The Thai Criminal Code, Sections 301 to 305, last amended in 1957, defines offences in relation to induced abortion as “any actions causing the delivery of a dead fetus”. Under Article 305, induced abortion can only be performed by a physician for two specific conditions, risk to the woman’s health and pregnancy arising from rape. Several problems arise in the interpretation and implementation of this law.

First, there is no definition of “health” or whether it covers the whole range of physical and mental health and social well-being as defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) Constitution.Citation6 The courts tend to interpret health in the narrow sense of physical health only, according to several lawyers and public prosecutors (Personal communication, 2002). Upon official requests by the Medical Council in 2001 to interpret the meaning of health in the law, the Royal Institute replied that a broader interpretation, including physical and mental health, was correct. However, the Royal Institute has no juridical power. Second, although incest is not mentioned in the Code, in practice medical professionals consider incest a form of rape and abortions are generally provided (Personal communication, obstetricians and general practitioners). Third, in cases where women seek abortion as a result of rape, physicians are required under the Criminal Code to obtain proof from the police. However, in practice, most women are deterred from reporting rape to the police. Lack of proof and refusal by physicians force women to resort to unsafe abortion or continuing the pregnancy.

Lastly, although the law does not cover fetal indications, abortions are carried out by medical professionals on these grounds. In 1995 a teaching hospital was reported to have been charged with violating Articles 301 and 302 of the Criminal Code as it had terminated 362 pregnancies during 1981—85 of women with rubella infection, because it causes severe congenital malformations.Citation7

The reproductive health policy context

The policy goals of reproductive health, as stipulated by the Ministry of Public Health, are the effective prevention of unwanted pregnancies, adequate access to safe abortion when needed, prevention of unsafe abortions, minimising the incidence of complications from induced abortion and proper interventions to achieve these goals. It is therefore also necessary to have data on the magnitude and public health impact of induced abortion.

In the last three decades, there have been a number of dynamic debates and unsuccessful attempts to reform the Criminal Code in relation to abortion, to specify that health covers physical as well as mental health of the pregnant woman and to include fetal indications, i.e. severe congenital anomalies and genetic disease incompatible with life. Increasingly, the broader grounds of health and fetal indications have gained more acceptance socially as legitimate reasons for abortion. Social reasons, on the other hand, such as contraceptive failure, have not. Indeed, a proposal to include the latter led to strong opposition to reform in 1981.Citation8

The objective of this study, carried out over a period of one year in 1999, was to estimate the magnitude and profile of induced abortion in Thailand through a prospective study in sentinel public hospitals, and to make policy recommendations on how to reduce unsafe abortion. We intended to include all 830 public and approximately 400 private hospitals in the country,Footnote* but the private sector declined due to legal restrictions and the illegal nature of many abortions. Only the public hospitals were willing to participate.

Methodology and participants

Two main research methods were used, case record review and face-to-face patient interviews. In the case record reviews, all ambulatory abortion visits and admissions were examined for the whole of 1999. The diagnosis of spontaneous vs. induced abortion recorded by the physicians was to be based on the following WHO case definition criteria:Citation9

| • | Certainly induced abortion — when the woman herself has admitted it, or has told a health worker or relative (in the case of the woman dying), or there is evidence of trauma or of a foreign body in the genital tract; | ||||

| • | Probably induced abortion — when the woman has signs of induced abortion accompanied by sepsis or peritonitis, and the woman states that the pregnancy was unplanned; | ||||

| • | Possibly induced abortion — if only one of the “probably induced” conditions is present; | ||||

| • | Spontaneous abortion — if none of the conditions listed above is present, or if the woman states that the pregnancy was planned and desired. | ||||

For the purposes of this study, the first three case definitions (certainly, probably and possibly) were all classified as induced abortion.

Information about each abortion case was retrieved from the medical records by a designated hospital staff person and sent to the researchers each month, with a copy retained in the participating hospital for verification in case of unclear information. Data collectors were the attending physicians or obstetricians, assigned to the task by the participating hospital. Due to it being such a large-scale survey, it was not possible to train them all.

Data collected included the case ID number, woman’s age, number of weeks of pregnancy, history of abortion, number of living children, nature of abortion (spontaneous vs. induced), reasons for abortion (e.g. maternal health, rape, HIV infection, risk of congenital anomaly, fetal death in utero or other clinical indication). For cases with unclear information, telephone calls were made to the hospital staff referring to the case ID number. In-depth interviews with staff in a few participating hospitals were conducted to understand and verify the extent of mis-classification of induced abortions as spontaneous abortions.

Hospitals with a large number of induced abortion cases during the first two months of the review were invited to participate in a more detailed study of the socio-economic characteristics of the women, reasons for abortion, method of abortion, type of providers, complications and costs incurred. All the hospitals invited (134) were willing to participate. To obtain the data, face-to-face interviews with patients were conducted using a structured questionnaire. Hospital staff designated to do the interviews received one day of training from the researchers.

We aimed to interview a total of 2,000 women. Patients were interviewed until a quota of 20 (for district hospitals) and 40 (for provincial or teaching hospitals) was achieved. To prevent bias, we applied the principle that every consecutive induced abortion patient would be interviewed. Almost all the women concerned agreed to participate in the interviews. Note that the women interviewed were a sub-set of those in the case record review.

Participating patients and hospitals were protected for data confidentiality. The interviews were conducted during the second half of 1999 on the hospitals’ premises in a private room in the gynaecology ward.

The pregnancies of the women who comprised the study sample were terminated at less than 28 weeks of pregnancy. The women had either been admitted to hospital with symptoms related to spontaneous or induced abortion, or had had therapeutic abortions conducted in the hospital. Threatened abortion cases were excluded.

Results

Demographic data and abortion ratios

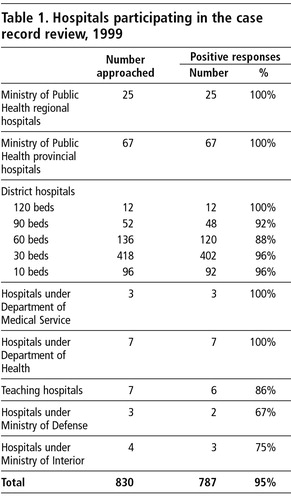

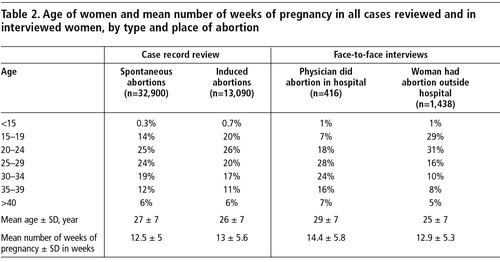

Of the 830 public hospitals, 787 participated in the case record review study, a 95% response rate (see ). shows the ages of the women and the mean number of weeks of pregnancy of the whole sample and of the sub-set of women who were interviewed.

There were a total of 45,990 abortion cases reviewed, of which 28.5% were classifed as induced and 71.5% as spontaneous abortions. A calculation of the hospital abortion ratio using the number of live births in the respective hospitals as denominators gave an induced abortion ratio of 19.5 to 1,000 live births and a spontaneous abortion ratio of 49.1 to 1,000 live births. The total abortion ratio was 68.7 to 1,000 live births. Seasonal variation was observed in most hospitals, a similar peak in spontaneous and induced abortion ratios was seen in February and March 1999.

Of the 13,090 women with induced abortions, 47% were young women of less than 25 years of age, of which 21% were adolescents. There was a lower proportion of adolescents (13.9%) with spontaneous abortions than induced abortions. The mean age of women with both spontaneous and induced abortions was similar, 27 years old. Most of the induced abortions (57%) took place at 9—15 weeks of pregnancy, while 16.8% were terminated at 20—28 weeks.

Women’s reasons for abortion and the law

Of the 13,090 women, the main reasons (60.2%) for induced abortion were not medical but socio-economic. The remaining reasons were medically-related, such as fetal anomalies (15.4%), intrauterine death (13.5%), the health of the woman (7.8%), HIV infection (2.2%), rape (0.6%) and rubella (0.3%). There were a much higher proportion of socio-economic indications for induced abortion among the younger women, i.e. 83.1% of adolescents in contrast to a higher proportion of medical indications among the older women, i.e. 55% among women aged 30 and above.

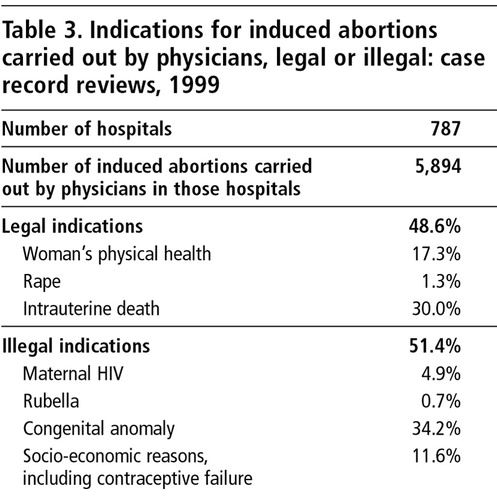

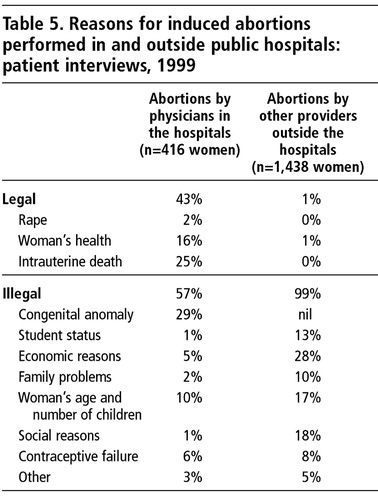

Physicians in the 787 hospitals carried out 5,894 of the 13,090 abortions, including most of the clinically indicated abortions, including those for fetal indications, such as rubella and HIV infection, although they were illegal. shows the grounds for the 5,894 abortions, divided between those that were and were not allowed under the law. Of those cases, approximately half (48.6%) complied with the law, namely for physical health of the woman (17.3%), rape (1.3%) and intrauterine death (30%), which we interpret as de facto legally allowed. The other half (51.4%) did not comply with the current law, but physicians judged them as necessary. These were for congenital anomaly (34.2%), HIV infection (4.9%), rubella (0.7%) and socio-economic indications, including contraceptive failure (11.6%).

Complications following abortion

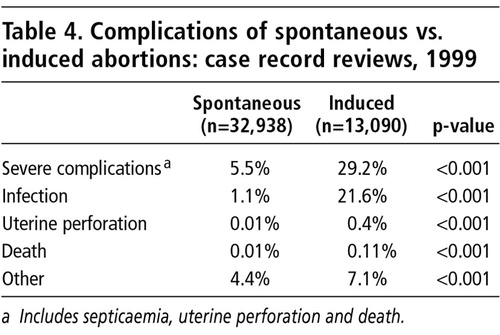

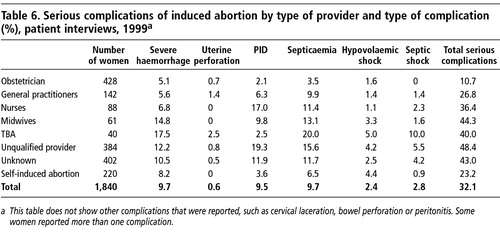

Of the 13,090 induced abortions, 29.2% had serious complications ( ), namely septicaemia (21.6%) and uterine perforation (0.4%) and there were 14 deaths (0.11%). Serious complications were five times higher among induced (29.2%) than spontaneous abortions (5.5%). The fatal complication rate was ten times higher among induced (0.11%) than spontaneous abortions (0.01%). It is likely that the fatal complications attributed to spontaneous abortion were in fact induced abortions but were misclassified due to self-reporting.

Profiles of the 1,854 women who were interviewed

There were a total of 1,854 women who had an induced abortion in the 134 selected hospitals who were willing to participate in the face-to-face interviews. Of these, 416 women had their abortion done by physicians in the hospitals and 1,438 by providers outside the hospitals. In the latter group of 1,438 women, 61.3% were less than 25 years of age, of whom 29.9% were adolescents. Nearly half (47.9%) of the 1,438 induced abortions were the woman’s first pregnancy and 86% had been unplanned; most (60%) of these women were married, 29% were single and 11% divorced or separated. In contrast, the marital status of those whose abortions were done by physicians in the hospitals was quite different: 93% were married, 4% single and 3% divorced or separated. Most of the interviewed women had low incomes and 41.7% had no regular income. Their occupations reflected their socio-economic status as minors and/or socially disadvantaged: 25% students, 21% labourers, 19% unemployed and 3.4% waitresses in restaurants.

About half of the interviewed women (52.1%) had not used contraception, 36.3% were irregular users and only 11.7% were regular users. Among the regular users, the pill was the most common method (60.8%) followed by condoms (18.2%), injectables (12.2%) and emergency contraceptive pills (10.2%).

The three most important reasons given for not using contraception were not expecting to become pregnant (61.6%), not expecting to have sex (17.7%) and not permanently living with their partners (17.2%). Other reasons included having experienced side effects with contraception (12.1%), inadequate knowledge of contraception (11.8%), being afraid of using a method (7.7%) and feeling too shy to ask for contraception services (7.5%).

compares reasons for the abortions performed by hospital physicians in this group of women and those by outside providers. Almost all the cases outside the hospitals were for socio-economic reasons, notably economic problems (28%), social problems (18%), woman’s age and number of children (17%). Less than half (43%) the induced abortions done in the hospitals were medically indicated (2% rape, 16% woman’s health and 25% intrauterine death).

The women were asked to rank their three most important reasons for having an induced abortion. Economic problems were ranked first by a majority (56.8%) followed by inadequate family planning knowledge and practice e.g. pregnant at an inappropriate age, short birth intervals or wanting no more children (34.4%), becoming pregnant but not ready for marriage (28.8%), still in school (26.8%), partner’s refusal to take responsibility and marry (16.1%) and failure of contraception (15.6%).

Abortion providers, method of abortion and complications

Of the 1,438 women who had abortions outside the hospitals, 34.9% were done by non-health personnel (of whom traditional birth attendants accounted for only 3.2%) and 28.7% by health personnel (either a physician, obstetrician, nurse or midwife); 36.3% were of unknown status.

Abortion techniques used included insertion of foreign substances or injection of a liquid solution into the cervical canal (40.6%), or use of a vaginal suppository (13.6%), oral tablets (11.6%) or strong manual compression of the lower abdomen (11.0%).

As a result ( ), 32.1% of all the induced abortions (inside and outside the hospitals) had serious complications, septicaemia (9.7%), haemorrhage (9.7%), pelvic inflammatory disease (9.5%), hypovolaemic shock (2.4%) and septic shock (2.8%). Five of the women whose abortions were unsafe had fatal complications (0.3%). gives a breakdown of serious complications by type of provider. A significantly higher percentage of serious complications were caused by unqualified personnel (48.4%), midwives (44.3%) and providers of unknown status (43%).

Discussion: which reasons for abortion should be made legal

This study provides the first large-scale hospital-based survey of abortion in Thailand and estimate of the abortion ratio to live births. The numbers are of course an underestimate since women who had an abortion but had no access to hospital care and those attending private hospitals were excluded. As the data collectors were physicians or obstetricians in the participating hospitals, we have to assume their diagnosis as to whether abortion was induced or spontaneous, according to the WHO criteria, was fairly accurate. However, in-depth interviews with staff in participating hospitals revealed that a certain number of induced abortions were mis-classified as spontaneous in this study, especially in the “possibly induced” group.

Most induced abortions in Thailand are illegal, and community-based household surveys to record these events among women of reproductive age are extremely difficult to carry out.Citation10, Citation11 A public hospital-based approach in Thailand largely captures legal abortions for medical indications and those for women with complications who need hospital care. Access to care depends on fear of sanctions, geographic and financial accessibility, and social and health worker attitudes. Women are reluctant to admit to having undergone induced abortions and an indeterminately large number in community-based studies are probably mis-classified as spontaneous abortions. Thus, even with this large dataset, it remains difficult to assess the true magnitude of induced abortions.

We decided not to try to quantify the magnitude and rate of spontaneous versus induced abortions from this study to obtain a national average, due to two major drawbacks in our methodology. First, private sector hospitals and clinics were excluded, and the number of abortions in the private sector might be much higher than in public hospitals. Second, our samples could be biased towards cases with complications requiring hospital care and therefore unrepresentative. However, it costs less to obtain data from a very wide geographical area using a hospital-based approach.

Due to poor quality of medical records in some cases, there were missing values of some key parameters. This weakness was reduced by prospective interviews with women, which provided useful information on reasons for abortion and a socio-economic profile of patients not adequately captured in the medical records. While hospital premises are not a neutral place for conducting interviews, it was more cost-effective than interviews in women’s homes and women may have been less willing to be seen at home.

Patient interviews indicated that socio-economic reasons were the main reasons for induced abortion outside hospitals, especially among young women. We therefore recommend a more conducive environment for empowerment of young women through the effective dissemination of knowledge through sex education and social life skills, which has also been identified as critical in other Asian countries such as India.Citation12, Citation13 Despite a successful family planning programme for married women in Thailand, unmarried women and adolescents are far from adequately covered. Social attitudes are the key barrier. Women-centered provision of family planning services, particularly for adolescents, and effective post-abortion counselling and services to prevent repeat abortions need more policy attention. Commitment to sustained public education would also be beneficial.

Inadequate understanding of proper use of contraceptive methods among regular contraceptive users leads to contraceptive failure and unplanned and unwanted pregnancies. Moreover, the current law in Thailand does not allow failure of contraception as an indication for induced abortion. A significant proportion of unwanted pregnancies due to failure of contraception could be prevented through better quality family planning services. However, there is a need for social consensus on whether the failure of both female and male sterilisation should become one aspect of legal reform.

More social support for single women who elect to continue their pregnancies is needed, e.g. changes in college regulations allowing pregnant students to continue with their studies. Moreover, the enforcement of the Labour Protection Act to prevent discriminatory practices against pregnant women in employment is urgently needed. At times, women are forced to terminate a pregnancy to keep their jobs and must risk unsafe abortions.

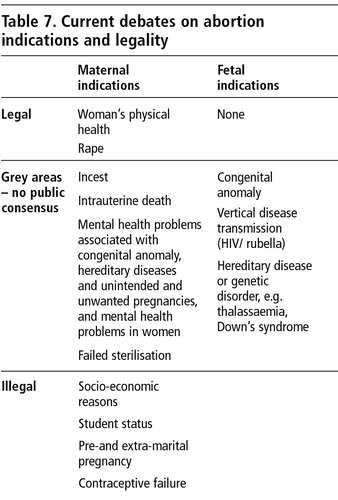

Based on the current law and women’s reasons for induced abortion from this survey, a matrix was formulated in in line with . The grey areas are the indications where there is controversy whether to include them in legal reforms. The “illegal” area contains indications that are unlikely to be legalised in the near future.

As regards the grey area for maternal indications, how should medical professionals and the courts interpret pregnancies resulting from incest. Is incest a form of rape? Intrauterine death is easily interpreted and well accepted socially as an indication for inducing abortion. Mental health problems for women related to pregnancy, especially due to congenital anomaly and hereditary diseases, have invited strong disagreement in the past. Opponents confine their argument to the right to life of the fetus and that society must protect their rights by all means. Some physicians, lawyers and women activists have had a different proposal: that pregnant women should have more rights than the fetus before 12 weeks of pregnancy while the fetus should have more rights after 12 weeks. These views have appeared in newspapers when debate on these issues has been reported.

In practice, some physicians in participating hospitals said in in-depth interviews that they provide abortion if sterilisation fails on the grounds that it is easier to prove failed sterilisation than that a reversible method has failed. It may not take a massive effort to move the medical profession to accept that failed sterilisation warrants legal abortion.

As regards the grey areas for fetal indications, congenital anomaly and vertical disease transmission of HIV or effects of rubella are more flexibly interpreted by physicians. However, lower HIV transmission rates of around 8—10%,Citation14 as a result of a nationwide prevention of mother-to-child transmission programme initiated in 1999, have led some medical professionals to speak out against the need for abortion to prevent vertical HIV transmission. Women’s health activists respond that an 8—10% chance of newborn HIV infection is still very high, and women should be given the option of abortion. Even if there were no vertical infection, the baby would become an orphan when the mother dies of AIDS. Women should therefore have the choice and the right to abortion after counselling. Hereditary diseases such as thalassaemia major and Down’s syndrome also generate controversial debates. We believe that some of the maternal and fetal indications falling in the grey area, for example, incest, intrauterine death and mental problems could be made part of legal reforms.

On the other hand, opinions published in the media regarding socio-economic indications were that they should not be allowed as a legal indication for abortion. Unfortunately, there were no views published from the women who face all the problems of unwanted pregnancy. We also foresee great difficulties with some of the fetal indications, for example, thalassemia, though strategies could be worked out in some cases. These indications may warrant further public debate.

This study found that fewer than half (48.6%) of induced abortions carried out by public hospital physicians complied with the current law in 1999. Hence, a broader interpretation of maternal and fetal indications in law would support improved access to safe abortions, and legal reform is needed to take into account new perspectives and actual practice of the medical profession. However, we must draw lessons from historical efforts that amendments to the law approved by the House of Representatives in 1981 failed in the Senate, primarily due to the lobbying efforts of Chamlong Srimuang, the leader of a broad-based religious coalition.Citation8

Abortion remains a politically sensitive issue, and the sensationalism used in the media to counter reform efforts, based on conservative religious dogma, should not be underestimated. We need to obtain views from all sides to determine further reforms in future. A multi-faceted approach to reduce and prevent the number of unwanted and unplanned pregnancies is needed, with special attention to the most vulnerable groups of women. A recommendation to amend the abortion law was drafted by a coalition of medical professionals, academics, lawyers, women’s organisations, public health advocates and National Reproductive Health Programme managers in 2003 and proposed to the Ministry of Public Health and the Thai Medical Council for further action. Though the law reform recommended in this proposal will not directly benefit the large proportion of women who seek abortions for socio-economic and family planning reasons, it is still very much worth moving ahead with it.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the assistance of the staff in all participating hospitals in this project, without whose enthusiastic contributions this paper would not have been possible. This study was supported by the World Health Organization country budget for Thailand. Thailand Research Fund programme grants to the Senior Research Scholar Programme in Health Policy and Systems Research are also highly appreciated.

Notes

* The public health care system in Thailand includes more than 700 district hospitals, covering all districts, and 92 provincial/regional hospitals in all 75 provinces. Private hospitals have less than 20% of the total number of beds nationally.

References

- World Health Organization. Unsafe Abortion: Global and Regional Estimates of Incidence and Mortality in 2000. 2004; WHO: Geneva.

- P Rattakul. Septic abortion Journal of Medical Association of Thailand. 54(5): 1971; 312–319.

- Department of Medical Services. Annual Hospital Report. 1984; Ministry of Public Health: Bangkok.

- Bureau of Health Policy and Planning. Annual Report on Health Statistics. 2000; Ministry of Public Health: Bangkok.

- A Koetsawang, S Koetsawang. Nationwide Study on Health Hazards of Illegally Induced Abortion. A Research Report. 1984; Ministry of Public Health: Bangkok.

- World Health Organization. WHO Constitution, Basic Document. 2002; WHO: Geneva.

- Matichon Daily (Bangkok). 4 April 1995.

- A Whittaker. The struggle for abortion law reform in Thailand Reproductive Health Matters. 10(19): 2002; 45–53.

- World Health Organization. Studying Unsafe Abortion: A Practical Guide. WHO/RHT/MSM/96.25. 1996; WHO: Geneva.

- W Bleek. Lying informants: fieldwork experiences from Ghana Population and Development Review. 13(2): 1987; 314–322.

- BA Anderson, K Katua, A Puur. The validity of survey responses on abortion: evidence from Estonia Demography. 31(1): 1994; 115–130.

- GI Allahbadia, V Ambiyd, P Vaidya. Adolescent sexuality, pregnancy and abortion Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology of India. 40(2): 1990; 152–155.

- B Ganatra, S Hirve. Induced abortions among adolescent women in rural Maharasthra, India Reproductive Health Matters. 10(19): 2002; 76–85.

- Department of Health. Programme evaluation of Prevention of Mother to Child Transmission of HIV (Internal report). 2001; Ministry of Public Health: Bangkok.