Health and Hope, Rights and Responsibilities: Action Agenda, Global Roundtable: Countdown 2015

All of us came to London this week with a vision: a vision shaped by Cairo and based on a profound respect for the human rights of all people–women, young people, people of all sexual identities, and–yes–political and religious conservatives. I hope we leave here tonight with our vision revitalized, our commitment renewed, and our creativity and energy recharged.

My main task is to report back to you, and to the broader community, the key decisions and recommendations that have emerged from your hard work during the past three days. Before I do so, I want to share some realizations and insights that have struck me as I have looked back, listened and tried to learn.

First, we need to recognize the measurable and promising progress that we have made in some areas of sexual and reproductive health and rights. In education, access to contraception, infant mortality and skilled care during childbirth, indicators have improved significantly over the past ten years. Donor funding for sexual and reproductive health, at least in the last two years, has increased–even if it is still far from where it needs to be.

Second, we need to recognize the battles we have won. The Cairo consensus has held. Governments around the world have adopted the framework as their own, and are implementing it–slowly, perhaps, but they have begun. And they have publicly expressed their commitment, reaffirming ICPD in regional meetings over the past 18 months–as in Santiago and San Juan, where the Latin American women's NGOs set a high standard for how to organize and mobilize. The opposition is strong, unified, and relentless; but we should be proud of our success in beating them back, and build on it.

Third, we need to recognize how much we have learned, and how we have absorbed the principles and language of Cairo into our thinking and our work. The Programme of Action was not perfect; its language on abortion is ambiguous, its commitment to the rights of young people did not go far enough, and its timidity on sexuality and sexual rights has held us back. But reading its 16 chapters again, it is remarkable how progressive and forward-looking the document was, forged as it was in an extraordinary meeting of 179 government delegations, hundreds of NGOs, and over 1,000 young people who came together and organized for the first time around these issues.

We are not where we need to be; there are no illusions about that. And we risk falling further behind if we do not effectively link our goals to the broader development agenda, and ensure buy-in from the broader development community. But these goals are not unreachable–and this week's conference has helped us come together, to see how far we have come, and to begin the journey into the next decade.

We had a packed agenda for this conference; it is my duty and privilege to unpack it for you now and share some of the highlights and recommendations that each of the agenda-setting sessions has produced in the past three days–keeping in mind that the full richness of the discussions and recommendations will only be reflected in the conference report, which will be on the website.

Youth

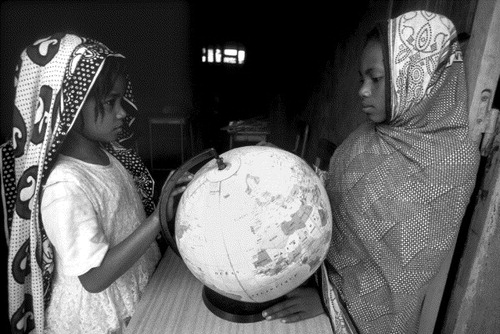

Within our movement, young people are in a different place than they were ten years ago. Their role in this conference–as planners, leaders, and spokespersons–demonstrates what they have fought for, and earned. Around the world, governments have adopted policies (if not always laws) that recognize young people's sexual and reproductive health needs (if not always their rights). Our and their priorities for the next decade are as follows:

Rights: It is essential to respect and promote young people's human rights–including their sexual and reproductive rights–on the same terms as adults. These rights cannot be curtailed because of their age or the wishes of their parents.

Participation: Young people and adults need to work together on sexual and reproductive health and rights in true partnership and respect, with young people involved in decision-making, planning, implementation and monitoring–and not just of youth programmes. Institutionally and individually, we must all make the commitment to this involvement, and invest in training and skill-building to make it possible.

Gender equality: Education is key to gender equality–not just equal access to formal education for girls, which is fundamental; but also education of families and communities. Mass media and the internet, as well as religious institutions, are enormous influences, as other sessions of our conference made clear; and we have heard of innovative ways to reach them and use them. In this, no doubt, young people are indeed our leaders.

Youth-friendly services: As in the past, NGOs have shown the way in piloting creative ways to make services more acceptable and accessible for young people. Governments are beginning to follow suit, but training of health workers to encourage tolerance and understanding, policies to guarantee confidentiality of young clients, and other youth-friendly changes need to be incorporated into the basic structure of health services.

Sexuality education: From “family life” education in the 1980s and 1990s, with incomprehensible pictures of female reproductive organs and “just say no” messages, to honest and open discussions of sexual pleasure and identity–perhaps in no other area of youth programming have we come so far. But curricula need to be more tailored to different age groups, better address issues of self-esteem and self-image, and educators–whatever their age–need training in working with young people.

Finally, all policies and programmes need to recognize that youth are no more monolithic than adults; rural youth, married adolescents, and out-of-school youth are especially likely to be ignored. The investment to reach them may be harder, but the key is always involvement–support them, and they will show us the way.

HIV/AIDS

Even at the time of the Cairo conference the numbers and impact–perhaps too enormous to absorb–were there: the Programme of Action estimated between 30 and 40 million infected with HIV by the end of the decade, and we are now at the top end of that projection. Although committed activists were already ringing alarm bells, few of us were listening enough to imagine the devastation it would wreak on our families and societies, the heartbreak and the economic disintegration it would cause. We do have a few beacons of hope: drugs that, where available, make HIV a chronically managed condition; prevention approaches that offer the information, insights and skills to reduce rates of infection; and greater political commitment and resources.

Perhaps in no area of sexual and reproductive health has our knowledge and understanding changed so much since Cairo as in HIV/AIDS. Our focus here in London was to examine the linkages between HIV/AIDS and sexual and reproductive health, building on discussions in Glion, Switzerland, New York and Bangkok over the last few months. The mainstreaming of HIV/AIDS into our policies, programmes and practice will enable us to meet the sexual and reproductive rights and aspirations of HIV-positive people. Access to integrated prevention, treatment and care must now be an integral part of our action agenda. However, we all need to deconstruct what we mean by the term “sexual and reproductive health”, so that irrespective of the communities we represent, we speak a common language. The basic principles of the Programme of Action are reflected in the recommendations from our discussions here:

Policies and programmes cannot be effectively designed, implemented or evaluated without the full engagement of networks of HIV-positive people and affected communities.

Linkages must be pursued at the funding, advocacy, policy and programme levels, globally and nationally. One example of such linkages is the “Three Ones” approach, which encourages governments to build relationships with all significant actors, including sexual and reproductive health NGOs, to truly integrate sexual and reproductive health and HIV/AIDS strategies.

Addressing the sexual and reproductive health rights and needs of those who do not form our traditional client base, such as youth, men who have sex with men, injecting drug users and sex workers, is an obligation which we must meet.

Existing services for people living with HIV/AIDS must be of higher quality and more accessible, offered without stigma or blame, based on a full recognition of their rights and tailored to the realities of their lives.

Existing structures and providers for sexual and reproductive health can and should respond to HIV issues. Both in the health system and in wider community contexts, the multiple entry points for the mainstreaming of HIV/AIDS into sexual and reproductive health need to be improved. These include voluntary counselling and testing, condom promotion and access, prevention of mother-to-child transmission programmes, antiretroviral access and management and treatment of sexually transmitted infections.

Social and cultural factors that define masculinity and shape men's role in HIV/AIDS, and the implications of these factors for their sexual partners, male and female, need to be addressed.

Advocacy against repressive legislation and practices, which increase vulnerability and discourage health-seeking behaviour, needs greater priority.

Resources

The Programme of Action estimates the annual cost for universal access to sexual and reproductive health services as more than $23 billion for 2005, or $18.5 billion in 1994 dollars; donors committed to provide one-third. While aid levels have increased recently, donors would still need to triple their giving to meet ICPD goals. The costs of the HIV/AIDS pandemic, including treatment and care for orphans, are least $10 billion more than estimated in 1994. Generating the resources to meet the 2015 goals will require:

Civil society and parliamentarians need to push donor countries, including the new emerging donor nations, to reach and/or maintain the allocation of 0.7% of national income for official development assistance. They must make the case for sexual and reproductive health to receive an appropriate share of this aid. And concerted action must be taken to close the alarming and growing gap in the availability of reproductive health supplies.

Governments, officials, parliamentarians, NGO representatives and recipient countries should participate actively, fully and effectively in budget allocation processes. We must be able to make the case convincingly for investing in sexual and reproductive health, demonstrating the economic as well as the social benefits of key interventions.

We must improve the tracking and transparency of financial and resource flows, and improve coordination of donor efforts. Different and better indicators for measuring progress must be defined and agreed to. These should go beyond the ICPD and MDG goals and should include supplies and human resources as indicators. Issues of quality of care, gender equality and respect for human rights must be taken into account in the funding, design and delivery of services.

Abortion

While the discussion on abortion at Cairo focused primarily on the public health impact of unsafe abortion, the Programme of Action also affirms a woman's right to make decisions about whether and when to have children. Since Cairo, in spite of the increase in post-abortion care programmes and efforts in many countries to change the law and make safe services more accessible, many barriers remain, abortion is still a major cause of women's deaths, particularly among young, poor and rural women.

Women have abortions whether they are safe or unsafe, and their reasons for abortion need to be respected. Making abortion safe, accessible and legal requires a broad range of actors, including women's, youth and community organizations, government policy-makers, trade unions, health and legal professionals, parliamentarians, researchers and journalists. All stakeholders should work to do the following:

Ensure that existing laws are fully implemented and not restricted further.

Establish laws, norms and regulations that make safe, legal abortion accessible and available to every woman who needs it, free from the threat of violence or coercion.

Improve access to family planning services to reduce unwanted pregnancies.

Ensure that post-abortion care and safe abortion services, a choice of surgical and medical methods, which can be provided by both doctors and mid-level providers, are included in both public and private health services.

Remove obstacles that currently exist in many restrictive laws when drafting new laws.

Implement these recommendations in line with principles of social justice and human rights, and using WHO's Safe Abortion: Technical and Policy Guidance for Health Systems 2003 and the WHO Reproductive Health Strategy 2004.

Sexuality

As Sonia Correa has pointed out, whether we acknowledge it or not sexuality is always there, lurking behind our discourses and practices. But just talking about sex is not enough; we need to examine our prejudices and taboos, and accept sexuality as an area in which rights–the rights to liberty, equality, personhood and freedom from shame and fear–all apply. There has been progress by human rights bodies in addressing these rights; this progress needs to continue and to take on the challenge of recognizing sexual orientation and gender identity as human rights issues, while also recognizing that sexual rights belong to us all.

A critical step for meeting this challenge is to ensure comprehensive sexuality education for people of all ages that addresses gender roles and power relationships and that embraces sexual diversity. Sexuality education should not just be about disease and protection, but about pleasure and freedom. Young people need to have the information and means to make their decisions about sexuality, and be supported in those decisions.

Poverty

The Cairo Programme of Action was revolutionary in recognizing that ending poverty, promoting development and addressing population concerns are inextricably linked to a range of social justice goals–gender equality, women's empowerment and human rights. In examining these issues over the past three days, participants in the poverty agenda-setting group agreed that:

Government investments in making health services accessible to the poor, especially women and young people, are an effective poverty-eradicating strategy. These investments are woefully inadequate at present, but could be increased through measures such as taxes on financial transactions.

It is critical, however, that these investments restore public health systems. In country after country, current health system models based on privatization and unregulated markets have failed the tests of equitable access and social justice. We need to make better use of existing health sector resources; re-allocate overall budgetary resources to prioritise health, including sexual and reproductive health; and within the health budget, focus investments in services and geographic areas that are most likely to reach the most vulnerable and the neediest.

Health decision-making at the public level must be accountable to women, the poor, minorities, migrants, indigenous peoples and youth, enabling them to voice their own needs. Mechanisms such as people's health councils must be a recognized aspect of citizenship rights and be part of implementing the Cairo agenda. Governments must be held to account by their own people–not just by international bodies–for the commitments they make in global and regional meetings and agreements, such as the MDGs.

Maternal health

As Fred Sai and Mahmoud Fathalla have pointed out, there is no more telling manifestation of gender inequity than the death of a woman from the complications of pregnancy or childbirth. Reducing maternal mortality, along with reducing HIV/AIDS, is among the most widely accepted ICPD goals, as reflected by its inclusion in the MDGs. But that does not mean it is necessarily well-funded, nor likely to be achieved. The group focusing on maternal health, which broadened its discussion to include newborn health as well, recommended the following:

Empowerment of women, families and communities, and encouraging a shared sense of responsibility for pregnancy is central to addressing the political, socio-economic, and cultural factors that so often prevent women from reaching good quality care. A woman's death must be seen as a cause for shame and reason for action by politicians, health workers and all those around her.

Functioning health systems, from the community to the referral hospital level, are essential to preventing deaths from life-threatening obstetrical complications. One of the most critical needs to be addressed nationally, regionally, and internationally is the dire shortage of skilled health personnel in many countries. Governments must also ensure that health providers are working in a supportive and enabling environment with the supplies, equipment, infrastructure and service guidelines that enable them to do their job.

Human rights

The need for a human rights framework for sexual and reproductive health policy and programming has been a theme throughout this conference–in part because of the lack of such a framework in the MDGs and a lack of clear accountability mechanisms at the country level. Human rights provide norms and standards, legal obligations, and mechanisms of accountability for sexual and reproductive health. The sessions on this issue gave us the following insights:

Human rights organizations are one ideal mechanism for holding governments accountable for sexual and reproductive rights. Efforts to partner with these groups and engage them in our issues are still new; we need to strengthen capacity and understanding in both communities, and expand and support such efforts.

We need to ensure clarity when the term “rights-based approach” is used in relation to sexual and reproductive health and other public health issues. We need to challenge those who view a rights-based approach and a public health approach as distinct. We must better define how it can be applied to sexual and reproductive health in advocacy, service delivery and policy development.

Women's rights

As others have said, Cairo shifted the focus of population and family planning programmes from demographic targets to the rights and needs of individuals–especially women. Ten years on, women's rights activists met here in London to share what they have learned about successful and less successful strategies, and had this to share:

If women's rights are to remain at the centre of the global vision for development, there must be strategic partnerships within the women's movement and with others engaged in human rights, health and development. As we celebrate the acceptance of terms like rights and sexuality within the mainstream health agenda, our challenge is to find means to apply them in ways that will bring real change to the lives of all girls and women.

The Programme of Action emphasized the role of men. However, attempts to increase men's involvement have sometimes reinforced traditional power relations. What is needed is for men to engage in non-violent behaviour, and to support women's rights and gender equity.

Challenges

The Programme of Action has been one of most controversial and challenged UN agreements in the last 50 years. Sexual and reproductive health and rights have become targets of new attacks from conservative and religious right forces. We need to identify and understand the main forces that are threatened by the Cairo consensus, and are working actively to undermine it. In discussing the challenges posed by religious fundamentalists, the US Government, and opposition groups, participants highlighted the following strategies:

NGOs and governments that are committed to sexual and reproductive health and rights need to work together to observe and understand the strategies of the opposition and develop effective counter-measures. We must support government officials and delegations to resist inappropriate pressure from the opposition.

We must promote a more realistic and diverse understanding of “families”, as well as reach out to progressive religious voices and challenge those who distort religious teachings.

As Rana Abu Ghazaleh said in the challenges session yesterday, we need to promote the religious values of equality, mercy, forgiveness, tolerance, dialogue and acceptance that have been buried under violence, suppression, discrimination, shame and guilt.

I would like to end with an acknowledgement and a tribute to women activists from all parts of the world, north and south, east and west–many of whom are in this room–whose dedication, insight, and leadership shaped so much of what we now believe, and are trying to achieve. ICPD was not born, fully formed, in Cairo; the thinking and strategizing began many years before 1994, and was sometimes forged in battles with traditionalists who have since seen the wisdom of their arguments. Today, we owe the women's movement a tremendous debt, and our profound thanks.

In addition, we need to acknowledge the critical contributions of health workers, who have been the constant, daily force behind so much of what we have achieved over the past decade. Without them, the Cairo commitments would still be just words on paper.

As Mona Zulficar said on the opening day, the promise of Cairo has been made; there is no going back. You have accomplished this week much of what we dreamed about when we were first thinking about this meeting. You have identified both progress and shortcomings; you have produced specific and compelling recommendations for the future; and, above all, you have reaffirmed your collective commitment to realizing that glorious dream that was born in Cairo–and that will become a reality in this generation.