Abstract

Progress in the empowerment of Arab women was found to be low in a 2002 report. Yet Arab women’s status is not reflected in continuing high fertility, which in 2000 had dropped sharply in one generation to 3.4. This paper discusses why fertility decline could nevertheless have taken place in the Arab countries. Islam has not stood in the way of fertility decline, as Iran and Algeria show. From the mid-1970s to 1980s, subsidised consumption through oil wealth redistribution reduced the cost of children, and social conservatism kept married women out of the labour force, both of which promoted higher fertility. The early stages of fertility decline were mainly due to longer length of education of girls, rising female age at first marriage, e.g. 28 in urban Morocco and 29 in Libya, and entry into the labour force of young, single women. There is also a growing population sub-group of never-married young women. Collapsing oil prices and structural adjustment reduced household resources and became an effective fertility regulation factor. Girls born since the 1950s have not only been educated longer than their mothers, but also their fathers, which increases their authority. These factors, and women’s activism and civil and political lobbying for the reform of personal status now underway in a number of Arab countries, could all challenge the patriarchal system.

Résumé

D’après un rapport de 2002, les femmes arabes progressent lentement vers l’autonomisation. Pourtant, leur statut ne va pas de pair avec le maintien d’une fécondité élevée : en une génération, celle-ci a été ramenée à 3,4 en 2000. L’Islam n’a pas fait obstacle au déclin de la fécondité, ainsi que le montrent l’Iran et l’Algérie. À partir de la moitié des années 70 et pendant les années 80, les subventions à la consommation provenant de la redistribution des revenus pétroliers ont réduit le coût de l’éducation des enfants, et le conservatisme social a maintenu les femmes mariées à la maison, deux mesures qui ont stimulé la fécondité. La fécondité a commencé à diminuer principalement du fait de l’allongement des études des filles, ce qui a retardé l’âge du premier mariage, par exemple 28 ans pour les Marocaines urbaines et 29 pour les Libyennes, et l’entrée sur le marché de l’emploi des célibataires. Les jeunes célibataires sont aussi plus nombreuses. La chute des prix pétroliers et l’ajustement structurel ont régulé efficacement la fécondité. Les filles nées depuis les années 50 sont plus instruites que leur mère, mais aussi que leur père, ce qui accroît leur autorité. Ces facteurs, ainsi que l’activisme des femmes et les pressions pour la réforme du statut personnel en cours dans plusieurs pays arabes pourraient saper le système patriarcal.

Resumen

En un informe del 2002 se encontraron muy pocos avances en la empoderación de las mujeres árabes. No obstante, el estatus de las mujeres árabes no se refleja en la continua fertilidad elevada, que en 2000 había disminuido marcadamente a 3.4 en una generación. En este artículo se examinan las causas de esta disminución en los países árabes. Islam no ha obstaculizado el descenso de la fertilidad, como se observa en Irán y Argelia. Desde mediados de los años setenta hasta los ochenta, el consumo subsidiado mediante la redistribución de la riqueza petrolera redujo el costo de tener hijos, y el conservadurismo social mantuvo a las mujeres casadas fuera de la fuerza de trabajo; ambos factores promovieron una fertilidad elevada. Las etapas iniciales de la disminución de la fertilidad se debieron principalmente a una duración más larga de la educación de las niñas, un ascenso en la edad de las mujeres al primer matrimonio, p. ej., 28 en Marruecos urbano y 29 en Libia, y la entrada de las mujeres jóvenes solteras en la fuerza de trabajo. Existe, además, un creciente subgrupo demográfico de mujeres jóvenes que nunca se han casado. Los bajos precios del petróleo y el ajuste estructural disminuyeron los recursos hogareños y constituyen un factor eficaz en la regulación de la fertilidad. Las niñas nacidas a partir de los años cincuenta han recibido una educación más larga que ambos padres, lo cual aumenta su autoridad. Estos factores, y el activismo y cabildeo civil y político de las mujeres con el fin de reformar su estatus personal, actualmente en curso en varios países árabes, podrían retar el sistema patriarcal.

The stark picture of human development in the Arab world painted in a report written for the United Nations by leading Arab researchers became the subject of impassioned debate in late summer 2002. They found that it was being seriously undermined by failings on three fronts: civil and political freedom, knowledge production and dissemination, and empowerment of women.Citation1 All – but especially the latter – are seen as the main factors of demographic transition, especially fertility reduction. Women’s status, therefore, should be reflected in continuing high fertility. But is that the case?

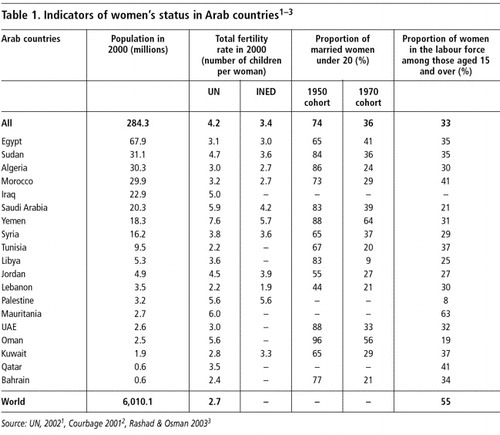

The average total fertility rate (TFR) for the Arab world was 3.4 children per woman in 2000. Still high compared to the world average (2.7), it is low compared to the six to eight children per woman which was the norm for the previous generation. So fertility has dropped sharply. Compared to Asian or Latin American countries at the same level of economic development, the decline onset later in the Arab world, but once under way progressed so fast that international statistical yearbooks were taken unawares and almost invariably overestimate the true TFRs (Citation2).

Arguably, then, the Arab countries would present a paradox of fertility decline without women’s empowerment. And yet the causes of fertility decline are universal: in the Arab world as elsewhere, it stems from the changing role of women and the place of children in the family and society, in the wake of the radical changes in today’s world, not least urbanization, the shift to service economies and the spread of education. Why have these causes been so late-acting in the Arab world? Is it down to the Islamic religion and culture, or to economic and political factors?

Oil and fertility

Late-starting fertility decline in the Arab world – and in other parts of the Muslim world – is commonly attributed to the influence of IslamCitation4 in supposedly holding back the two agents of demographic change – women’s autonomy and the emergence of civil society organizations that promote community self - empowerment – by harnessing the former to the yoke of male authority and the latter to that of political authority. And yet, whether as a State or grassroots religion, Islam has not stood in the way of radical demographic changes. Cases in point are the Islamic Republic of Iran – a country which, though ruled by the most fundamentalist of clergies, may well have experienced one of the most rapid fertility declines in historyCitation5 – or Algeria, where fertility collapsed in the 1990s at the very time when Islamic fundamentalism was gaining most strength among the population.

Islam, however, is not all that Arab countries have in common; they also have a heavy economic dependence on oil revenues: either directly in the case of major oil exporters (Saudi Arabia, Iraq and the Gulf States in the east, Libya and Algeria in the west), or indirectly for the other countries, where oil wealth has a major impact through development assistance, private investment and migrant workers’ remittances. The oil economy experienced an unprecedented boom in the 10–12 years after the 1973 Arab–Israeli war, one immediate consequence of which was to send oil prices soaring. The sudden change in scale of oil revenues (crude oil rent) enabled Arab governments to establish welfare state systems through financing development (health, education, etc.) and subsidising consumption.

While development activities were conducive to fertility decline, subsidised consumption, by reducing the cost of children, could work to the opposite effect. This is what happened in a number of Arab countries, especially the most oil-rich ones, whose governments, by keeping the population in check through generous oil wealth redistribution, were able to play the forces of conservatism and change off against one another. Social conservatism was reflected in particular by a continuing very low labour force participation rate among married women. So, by both cutting the costs of fertility and keeping women in the home, oil revenues indirectly promoted high fertility. To some extent, oil revenues “generated” population.

The onset of the oil crisis in the mid-1980s put an end to this. Collapsing oil prices slashed revenues and all countries, apart from the Gulf States, were quick to bring in economic reforms from which families lost out. Age at marriage rose, a trend fuelled by the practice acquired in the heady oil-rich days of amassing a substantial marriage dowry, which now took many years to scrape together. Married couples had smaller families, as they continued to nurture the aspirations held for their children during the good times, while life grew dearer. This succession of economic cycles widened the generation gap between the children of the welfare state and those of structural adjustment.Citation6

An emerging group: young never-married women

The early stages of fertility decline in the Arab world were mainly due to the rising female age at first marriage.Citation3Citation7 Three quarters of girls in the 1950 birth cohort married under the age of 20, compared to just one third in the 1970 birth cohort. Mean age at marriage had risen from under 20 to over 25 in barely a generation.

Why should women’s age at marriage have risen so fast? A longer length of education is one reason. That explains the decline in early marriages, but not the high incidence of very late marriages: the vast majority of girls are now educated up to the age of 15, but still only a minority remain in education after age 20. The proportion single among young women aged 20–24 is therefore much higher than their enrolment ratio: 47% against 10% in Syria (1994 census), 84% against 17% in Tunisia (1994), 56% against 18% in Egypt (1996).

Employment is another reason for delayed marriage. It is not yet wholly acceptable in Arab societies for a married woman to work outside the home. In the Arab countries covered by the fertility surveys of the 1990s, the average participation rate was 31% among single 25–29 year-old females against 18% among married women of the same age group with (18%) or without children (17%): clearly, marriage more than motherhood is what prompts women to forsake working life. By putting a growing number of women on the labour market, the economic changes under way – growth in women-dominated occupations (teaching, health, administration, etc.) and declining living conditions from the end of the welfare state – have therefore arguably contributed to delayed marriages.

Delayed marriage tends to be construed as evidence of the empowerment of Arab women. The two reasons cited above – rising educational levels and entry into the labour force – argue in favour of that interpretation, in that for many young women, their unattached years are a time for acquiring skills or material assets, and for self-fulfilment. But empowerment is not absolute, as single women remain under the authority of their father or legal guardian. They live with their family until marriage, as do the overwhelming majority of young people: in the working-class districts of a large metropolis like Cairo, male students and soldiers are the only single people to live away from their family of origin. The lengthening premarital period, sometimes beyond age 25 and even to almost 30 (28 in urban Morocco, 29 in Libya), has created a population subgroup of never-married young women. This new group has not yet carved out its own place in society, still less secured legal recognition.

Increasingly better educated, but less economically active than men

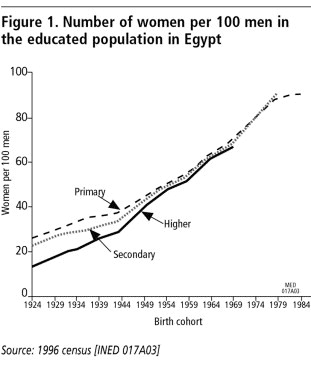

The number of veiled women about the streets of many Arab cities is growing. Is this a reflection of resurgent religious devotion? Or simply that more women are to be seen in the public space because the Islamic veil allows them to move around freely? Education is what has really allowed girls, previously confined to domesticity from the age of puberty, into the public space. But has it gone as far as full gender equality in education? Egypt has witnessed a steady birth cohort-specific improvement in the deficit of girls in the school population (). Egypt, which is averagely-placed in this respect, reflects a reassuring picture of a steady advance towards gender equality. The once chiefly male school population (barely one girl to three boys in the cohorts born around 1930) has now become nearly gender equal in primary and secondary education (90 girls to 100 boys in the cohorts born around 1980), and seems well-advanced in university education (66 girls to 100 boys in the 1970 birth cohort).

Unlike school, many workplaces remain relatively closed off to women. Labour statistics () show that Arab countries have the world’s lowest female participation rates. However, the evidence of a series of time-use surveys is that traditional statistical sources (censuses) underestimate Arab women’s real contribution to the economy, because it partly comprises homemaker activities, and census takers’ questions are usually answered by men who are unwilling to acknowledge the economic nature of such activities. Is it to take account of unrecorded female activities that international publications have significantly revalued (albeit on an unknown basis) the female participation rates reported in recent censuses: revalued from 14% (1996 census) to 35% in Egypt, from 15% (1998) to 30% in Algeria, from 21% (1994) to 41% in Morocco, from 23% (1994) to 37% in Tunisia? The fact remains that, even revalued, these rates remain low compared to the world average (55%).

Might not women’s low participation rates hold the clue to one means by which Islam has helped delay fertility decline? Lawyers argue that by recognising women’s right to own personal property, but not an obligation to contribute to family finances out of their income, the Shari’ah (Islamic law) increases husbands’ reluctance to allow their wives to work. But we must be wary of syllogism: legal provisions do not produce actual practices. The evidence of anthropological research is that economic realities outweigh legalism: in the crisis-hit urban classes, families not uncommonly rely on the wife’s income, prompting husbands to forego standing on their legal rights to restrict the main breadwinner's movements. In terms of family finances, women's work is a response to the decline in men's real wages.

Under the welfare state, women's low participation rates could partly explain their high fertility. Is the modest rise in female economic activity recorded in times of economic hardships reason enough for the collapse in fertility? Probably not. A more likely explanation is low household incomes compounded by low female participation. The welfare state had raised parents' aspirations and the level of their financial investment for their children, while structural adjustment now undermines their real resources. So, women's partial empowerment reflected by their low contribution to household incomes becomes an effective fertility regulation factor.Footnote* This could explain the paradox stated above of a fertility transition unaccompanied by (total) empowerment of women.

The end of the patriarchal system

What prospects might these trends foreshadow? Demographic change is undermining the patriarchal system which has governed the family system since time immemorial. That system rested on two pillars: younger brothers' subordination to the eldest brother in sibling relationships, and girl–women subordination to males within the family or marriage unit. Fertility decline undermines the first pillar. The modern trend towards two-child families – on average a boy and a girl – quite simply lessened the scope for a hierarchy between brothers, for lack of brothers.

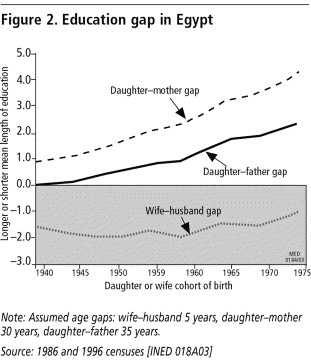

The second pillar can still be based on law, still modelled as regards personal status on the Shari'ah. But the gap between law and actual practices is widening. The rise in education levels has not only affected gender, but also generation, hierarchies. Measured by mean length of education, the educational attainment gap between children and their parents has grown steadily (). From the 1950s' birth cohorts, girls have not only been educated longer than their mothers, but also than their fathers. And since education is an element of authority, girls' overachievement compared to their fathers could well challenge the patriarchal system. On a cohort-for-cohort basis, women are now almost as well-educated as men, their labour force participation is bringing them in growing numbers into close contact with non-relative males with whom they are competing in the labour market. Women's activism and civil and political lobbying for the reform of personal status now under way in a number of Arab countries are likely to topple the patriarchal system from its increasingly shaky foundations.

Note

This is a reprint of Philippe Fargues. Women in Arab countries: challenging the patriarchal system? Population & Societies No.387, INED, February 2003, available at ⟨www.ined.fr⟩, reproduced in full with kind permission of the author and INED.

Notes

* Married women's non-participation increases the relative cost of children, while participation increases their opportunity cost (loss of earnings during spells out of employment for child-rearing).

References

- United Nations Development Programme and Arab Fund for Economic and Social Development. Arab Human Development Report 2002: Creating Opportunities for Future Generations. 2002; UN: New York.

- Y Courbage. Nouveaux horizons démographiques en Méditerrannée, Coll. Les cahiers de l'INED. 142: 1999

- H Rashad Hopkins, M Osman. Nuptiality in Arab countries: changes and implication. N. The New Arab Family: Cairo Papers in Social Sciences. Vol. 24/1-2: 2003; American University in Cairo Press: Cairo, 20–50.

- PS Morgan, S Stash, HL Smith. Muslim and non-Muslim differences in female autonomy and fertility: evidence from four Asian countries. Population and Development Review. 28/3: 2002; 515–537.

- M Ladier-Fouladi. Population et politique en Iran. De la monarchie à la République islamique. Coll. Les cahiers de l'INED. 150: 2003

- P Fargues. Générations arabes. L'alchimie du nombre. Fayard. 2000

- K Kateb. La fin du mariage traditionnel en Algérie? 1876–1998. Éditions Bouchène. 2001