Abstract

Learning about menstrual hygiene is a vital aspect of health education for adolescent girls. This study among 664 schoolgirls aged 14-18 in Mansoura, Egypt, asked about type of sanitary protection used, frequency of changing pads or cloths, means of disposal and bathing during menstruation. Girls were selected by cluster sampling technique in public secondary schools in urban and rural areas. Data were collected through an anonymous, self-administered, open-ended questionnaire during class time. The significant predictors of use of sanitary pads were availability of mass media at home, high and middle social class and urban residence. Use of sanitary pads may be increasing, but not among girls from rural and poor families, and other aspects of personal hygiene were generally found to be poor, such as not changing pads regularly or at night, and not bathing during menstruation. Lack of privacy was an important problem. Mass media were the main source of information about menstrual hygiene, followed by mothers, but a large majority of girls said they needed more information. Instruction in menstrual hygiene should be linked to an expanded programme of health education in schools. A supportive environment for menstrual hygiene has to be provided both at home and in school and sanitary pads made more affordable.

Résumé

L'hygiène menstruelle est un volet essentiel de l'éducation sanitaire des adolescentes. Cette étude a demandé à 664 étudiantes âgées de 14 à 18 ans de Mansoura, Égypte, le type de protection sanitaire qu'elles utilisaient, à quelle fréquence elles en changeaient, comment elles s'en débarrassaient et si elles se baignaient pendant leurs règles. Les filles, sélectionnées par échantillonnage par grappes dans des écoles secondaires publiques de zones rurales et urbaines, ont répondu en classe à un questionnaire anonyme, autogéré et à réponses ouvertes. Les facteurs prédisposant à l'utilisation de serviettes hygiéniques étaient l'accès aux médias à la maison, l'appartenance à une classe sociale élevé et moyenne et la résidence urbaine. L'utilisation de serviettes hygiéniques s'accroît peut-être, mais non dans les familles rurales et pauvres, et l'enquête a constaté d'autres manques, comme le fait de ne pas changer de serviette régulièrement, et de ne pas se baigner pendant les règles. Le manque d'intimité était aussi un problème important. Les médias représentaient les principales sources d'information sur l'hygiène menstruelle, suivis des mères, mais beaucoup de filles souhaitaient davantage de renseignements. Il faut lier les cours d'hygiène menstruelle à un programme scolaire élargi d'éducation sanitaire. L'environnement doit apporter un soutien en matière d'hygiène menstruelle à la maison et à l'école, et les serviettes hygiéniques doivent devenir plus abordables.

Resumen

El aprendizaje sobre la higiene menstrual es un aspecto vital de la educación en salud para las adolescentes. En este estudio realizado con 664 colegialas entre 14 y 18 años de edad, en Mansoura, Egipto, se preguntó acerca del tipo de protección sanitaria utilizada, la frecuencia con que se cambian las toallas, los medios de desecharlas y los baños durante la menstruación. Las niñas fueron seleccionadas por la técnica de muestreo por conglomerados, en escuelas secundarias públicas de zonas urbanas y rurales. Los datos se recolectaron por medio de un cuestionario anónimo, autoadministrado durante horas de clase. Los previsores importantes del uso de toallas sanitarias fueron: disponibilidad de los medios de comunicación en el hogar, clase social alta y media, y residencia urbana. El uso de toallas sanitarias posiblemente esté aumentando, pero no entre las niñas de familias rurales y pobres. Además, se encontraron deficiencias en otros aspectos de la higiene personal, como no cambiarse de toalla con regularidad o de noche, y no bañarse a diario durante la menstruación. La falta de privacidad fue un problema importante. Los medios de comunicación fueron la fuente principal de información sobre la higiene menstrual, seguidos de las madres, pero la gran mayoría de las niñas dijeron que necesitan más información. La enseñanza sobre la higiene menstrual debe vincularse a un programa ampliado de educación en salud en las escuelas. Se debe crear un ambiente de apoyo para la higiene menstrual tanto en el hogar como en la escuela, y las toallas sanitarias deben distribuirse a precios más asequibles.

The onset of menstruation profoundly changes young women's lives.Citation1 Good hygiene, such as use of sanitary pads and adequate washing of the genital area, is important during menstruation. Women and girls of reproductive age need access to clean, soft, absorbent sanitary products.Citation2Citation3Learning about hygiene during menstruation is a vital aspect of health education for adolescent girls, as patterns that are developed in adolescence are likely to persist into adult life.Citation4 Strips of towelling or cloth are not absorbent, lack cleanliness and may produce an odour.Citation5

Studies on menstrual hygiene among Egyptian women and adolescent girls are scarce. The Egyptian Fertility Care Society carried out a community-based study of the prevalence of female reproductive infections in Dakahlia Governorate, which was published in 1999.Citation6 It found that among ever-married older women, 15.3% used disposable sanitary pads, and 42.1% and 39.4% used re-usable cotton towelling after washing or boiling it, respectively. In contrast, 25.2% of unmarried younger women used disposable sanitary pads, 50.5% and 21% used re-usable cotton towelling which they washed or boiled after use. Only 3.2% of both groups of women used pieces of cloth that they threw away after one use.Citation4

In Mansoura, the capital of Dakahlia Governorate, located on the Nile River northeast of Delta, in Egypt, women can choose from a number of sanitary protection pads; tampons are not available locally. Pads come in different sizes, thickness and styles, depending on menstrual flow, and should be changed at least every 3-4 hours, regardless of the amount of staining, for comfort and to prevent odour.Citation2Citation6Tampons are mainly used by married women from higher socio-economic classes in urban areas.

School enrolment for girls has increased substantially in the past few decades, and schoolgirls require privacy during menstruation so as not to affect their school attendance. This study looked at knowledge and practice of menstrual hygiene among adolescent secondary schoolgirls in Mansoura. Menstrual hygiene practices were assessed in terms of the type of sanitary protection used, frequency of changing the method and means of disposal.

Population and methods

This study was carried out from November 2003 to April 2004. Approval of the local Directorate of Education and school administration was obtained. A cross-sectional survey was carried out among secondary schoolgirls enrolled in governmental general, commercial and nursing schools in both the Eastern and Western educational zones as well as the rural sector. Two general secondary schools were randomly selected in the urban sector, one each from the Eastern and the Western educational zones, and one school from the rural sector. One technical commercial school and one nursing school were also selected from Mansoura City. Together these schools represent different social strata as well as urban and rural sectors. From each of the five schools, three classes were randomly selected, one from each of the three different grades, or a total of 15 classes with a total of 694 female students. Of these, 664 participated in the study. The others were either absent (3.6%) or declined to complete the questionnaire (0.7%). The urban schools were all girls' schools while in the rural school there were separate classes for boys and girls.

In coordination with the school authorities, female co-authors Badawi and El-Fedawy spent 45-60 minutes in each class. The students were briefed about the study, encouraged to participate and motivated to express their experiences. It was emphasised that all data collected were strictly confidential. Students were requested to complete the self-administered questionnaire, which asked about their family background, age at menarche, sanitary protection used during the last menstrual period and their knowledge of different sanitary protection materials. The questions focused on the type of menstrual pads used, the disposal and storage of pads. The questions were open-ended.

The social score of Fahmy and El-SherbiniCitation7 was used to determine the family social class. This score encompasses parents' education and work, family size, crowding index at home, presence of mass media, methods of waste and sewage disposal as well as monthly per capita income. Data were analysed using Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) Version 10. The Chi-squared test was used as a test of significance. Significant factors affecting use of sanitary pads on univariate analysis were entered into multivariate logistic regression analysis with p≤0.05 considered statistically significant.

Results

The 664 schoolgirls were aged 14-18 years old. Twenty-two (3.3%) of them had not yet menstruated. Among the 642 who had menstruated, the age at menarche ranged from 10-16 years, with a mean and median of 12.9 and 13 years, respectively.

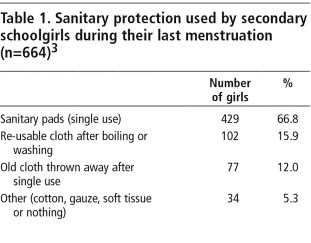

Two-thirds of the girls (66.8%) used sanitary pads, while 15.9% and 12% used re-usable cloths or old pieces of cloth thrown away after use, respectively (Table 1). The use of sanitary pads was significantly higher among girls enrolled in general secondary schools, the younger girls and girls from urban areas and higher social classes, with parents working as professionals or semi-professionals, with highly educated parents and with mass media available at home (data not shown). However, logistic regression analysis found that the biggest predictors of use of sanitary pads were presence of mass media at home (OR=12.7), high and middle social class (OR=5.98 and 3.96, respectively) and urban residence (OR=2.98).

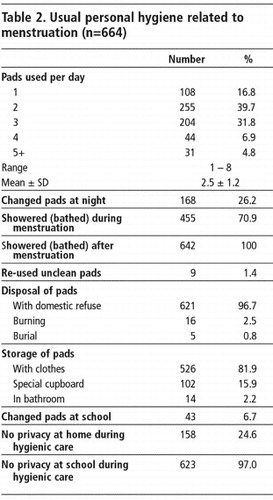

The girls changed sanitary protection 2.5 times per day on average, and 70.9% of them took showers (baths) during menstruation. The majority disposed of used pads with the domestic refuse (96.7%) and stored unused pads with their clothes (81.9%). Only 6.7% changed sanitary pads at school. Lack of privacy at home and school was reported by 24.6% and 97% of girls, respectively (Table 2).

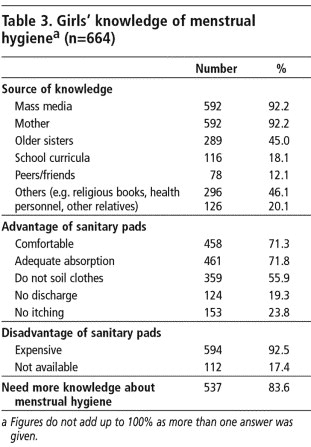

Mass media, peers and friends, and mothers were the most common sources of information about menstrual hygiene (Table 3). The perceived advantages of sanitary pads were that they were comfortable and provided adequate absorption, while the main disadvantages were that they were expensive or not available. 83.6% of the girls said they needed more information about menstrual hygiene.

Discussion

Poor menstrual hygiene has been shown to be responsible for certain reproductive tract infections.Citation8Citation9 Slightly more than two-thirds of the schoolgirls in this study used sanitary pads, while 15.9% of them used cloths they washed or boiled and 12% used pieces of cloth they threw away after use.

Multiple logistic regression identified the availability of mass media at home as the highest predictor of sanitary pad use, along with high and middle social class and urban residence. Clearly, lower socio-economic status, rural residence and lack of access to information about and money to buy sanitary products for menstrual hygiene are all related as well. In other rural, resource-poor settings a decade ago the situation was far worse, however. Studies in rural Bangladesh and India published in the mid-1990s found that most adolescent girls were using old pieces of cloth or even no protection at all during menstruation.Citation10Citation11 This appears to be changing for the better. In a more recent study in India, it was observed that younger women were more likely to use sanitary pads compared to older women.Citation12 The same observation was made in Egypt in 1999.Citation6

Nonetheless, apart from the method of protection used, menstrual hygiene was generally poor among the adolescent girls in this study. Nine girls (1.4%) reported the re-use of unclean pads. Only 11.7% changed pads four or more times per day and only 26.2% changed pads at night before going to bed. Avoiding showering or bathing is common during menstruation traditionally. In a study in Alexandria, Egypt, published in 1990, about one-quarter of girls avoided bathing during menstruation,Citation13 due to a belief, still common today in Mansoura, that the body is open during menstruation and that a cold shower or bath may cause retention of blood while a hot shower may increase bleeding.Citation14 Similarly, in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, 62.3% of girls abstained from showering during menstruation, as they believed it might stop the menstrual flow or increase the intensity of pain.Citation15 On the other hand, bathing after menstruation is a religious requirement in order to be able to pray and practise other religious obligations.

In Egypt, in poor areas, there is a problem of overcrowding and poor infrastructure both in schools and homes. Toilets may be totally absent or few in number, with broken doors or defective water supply and sewerage. No privacy for taking care of menstrual hygiene at home and at school was reported by 24.6% and 97% of girls, respectively. Although students spend a short time in school, as many schools have two and even three shifts per day, only 6.7% of girls changed pads at school. In schools attended by both sexes, the toilets for girls should be separated from those for boys. Lack of space and privacy were also reported in the recent Indian study mentioned aboveCitation13 and in an Iranian study among adolescents in Tehran suburbs, where 27% of the girls did not practise menstrual hygiene at all.Citation16

Because of cultural and religious beliefs in Egypt, menstruation is not considered an appropriate topic of discussion, leading to the lack of accurate and available information. In the present study almost all the girls (92.2%) reported the mass media as their source of knowledge about menstrual hygiene, followed by mothers (45%). In the 1990 Alexandria study, in contrast, mothers were the most common source of information on the physiology of menstruation before and after menarche, with school curricula and the media having a limited role.Citation13 Girls in all the studies mentioned here, however, variously point to the media, peers and friends, mothers, sisters and other female family members as their main sources of information.Citation16Citation17 In the Saudi study, however, about two-fifths of the girls had not discussed menstruation with anyone and had not received any information about it.Citation15 Girls in India in a study with comparable findings also said they needed more information.Citation18

The results of this study indicate a need for the establishment of a comprehensive school health education programme with strong familial input that includes instruction in hygienic practices related to menstruation. Teacher training should also include skills to be able to pass on accurate information to students. Girls should be educated about the selection of sanitary menstrual pads and their proper disposal, how to look after their menstrual needs when at school or away from home, and the lack of negative effects of bathing or showering, and encouraged to ask for help and to discuss their personal care needs with their mothers, teachers and appropriate health care personnel.

The role of the media and non-governmental organisations (such as women's associations and health committees of political parties) in such a programme is vital. Information can be provided through television commercials and drama in a socially and religiously acceptable way. There is also a need to make sanitary pads available at prices that are affordable to girls from poor families.

References

- R Snowden, B Christian. Patterns and perceptions of menstruation. A World Health Organization International Collaboration Study. 1983; St Martin's Press: New York.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Menstrual Hygiene Products. 1997; Medical Library.

- Harvey P, Baghri S, Reed P. Emergency sanitation: assessment and programme design. Water. Engineering and Development Centre, Loughborough University, UK, 2002. p.60.

- KA Narayan, DK Srinivasa, PJ Pelto. Puberty rituals, reproductive knowledge and health of adolescent schoolgirls in South India. Asia-Pacific Population Journal. 16(2): 2001; 225–238.

- Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia, Ministry of Health. Personal hygiene extension package. Addis Ababa. February 2004. p.17.

- Egyptian Fertility Care Society. Prevalence of female reproductive infections in Dakahlia Governorate. Final Report. 1999; EFCS: Cairo.

- SI Fahmy, AF El-Sherbini. Determining simple parameters for social classifications for health research. Bulletin of High Institute of Public Health. 13(5): 1983; 95–108.

- A Bulut, V Filippi, T Marshall. Contraceptive choice and reproductive morbidity in Istanbul. Studies in Family Planning. 28(1): 1997; 35–43.

- JC Bhatia, J Cleland. Self-reported symptoms of gynaecological morbidity and their treatment in South India. Studies in Family Planning. 26(4): 1995; 203–216.

- A Ali, SN Mahmud, A Karim. Knowledge and practice of NFPE-AGG graduates regarding menstruation. 1996; Bangladesh Rural Advancement Committee: Dhaka.

- DK Devi, VP Ramaiah. A study on menstrual hygiene among rural adolescent girls. Indian Journal of Medical Science. 48(6): 1994; 139–143.

- N Baridalyne, VP Reddaiah. Menstruation knowledge, beliefs and practices of women in the reproductive age group residing in an urban resettlement colony of Delhi. Health & Population Perspectives & Issues. 27(1): 2004; 9–16.

- MK El-Shazly, MH Hassanein, AG Ibrahim. Knowledge about menstruation and practice of nursing students affiliated to University of Alexandria. Journal of Egyptian Public Health Association. 65(5/6): 1990; 509–523.

- A El-Gilany, A Khalil, I Shady. KAP of adolescent schoolgirls about menstruation in Mansoura, Egypt. Bulletin of High Institute of Public Health. 34(2): 2004; 377–396.

- S Moawed. Indigenous practices of Saudi girls in Riyadh during their menstrual period. Eastern Mediterranean Health Journal. 7(1/2): 2001; 197–203.

- M Poureslami, F Osati-Ashtiani. Attitudes of female adolescents about dysmenorrhea and menstrual hygiene in Tehran suburbs. Archives of Iranian Medicine. 5(4): 2002; 219–224.

- A Barakat, SH Khan, M Majid. Adolescent sexual and reproductive health in Bangladesh: a needs assessment. Conducted for International Planned Parenthood Federation and Family Planning Association of Bangladesh. 2000

- S Garg, N Sharma, R Sahay. Socio-cultural aspects of menstruation in an urban slum in Delhi, India. Reproductive Health Matters. 9(17): 2001; 16–25.