Abstract

The medical abortion drugs mifepristone and misoprostol are now widely available in rural Tamil Nadu, India, and the practice of abortion is being transformed. This paper reports on current attitudes and practices concerning medical abortion among qualified abortion providers in a rural area of Tamil Nadu. Interviews were carried out with a purposive sample of 40 doctors, 15 informants at chemist shops, 10 village health nurses and 23 women who had recently had an abortion. Twelve of the 37 private doctors who were providing abortions, were providing medical abortion to 70-80% of their patients and 12 others to a selected minority. Eleven had largely rejected it and still used D&C; two had never heard of it. A number of doctors were using misoprostol for cervical dilatation prior to D&C. Some doctors and women who were concerned about incomplete abortion and heavy bleeding did not have a clear idea of what normal bleeding with medical abortion was. Incorrect regimens with second trimester medical abortions might have been responsible for cases of excessive bleeding. Most chemist shops said they were selling the tablets only on prescription, but doctors reported widespread over-the-counter sales. Medical abortion appeared to be quite acceptable to most women, and women were increasingly requesting it. Mechanisms are needed for sharing information about medical abortion among professionals, community health workers and rural families. The state government should develop a comprehensive plan for incorporating medical abortion into the public health system.

Résumé

La mifépristone et le misoprostol, médicaments abortifs, sont maintenant largement disponibles dans l'État rural du Tamil Nadu, en Inde, et la pratique de l'avortement en est transformée. Cet article examine les attitudes et pratiques actuelles concernant l'avortement médicamenteux parmi les prestataires qualifiés pour réaliser des avortements dans une zone rurale de l'État. Des entretiens ont été menés avec un échantillon de 40 médecins, 15 pharmaciens, 10 infirmières de village et 23 femmes ayant récemment avorté. Douze des 37 médecins privés qui pratiquaient des avortements utilisaient la méthode médicamenteuse sur 70-80% de leurs patientes et 12 autres sur une minorité choisie. Onze avaient rejeté cette méthode et recouraient encore au curetage ; deux n'en avaient jamais entendu parler. Un certain nombre de médecins utilisaient le misoprostol pour la dilatation avant le curetage. Des médecins et des femmes qui craignaient un avortement incomplet et de forts saignements n'avaient pas une idée claire de ce que sont des saignements normaux après avortement. Les pratiques erronées avec les avortements médicamenteux du deuxième trimestre sont peut-être responsables des cas de saignements excessifs. La plupart des pharmaciens ont affirmé ne vendre les comprimés que sur ordonnance, mais d'après les médecins, les ventes libres étaient fréquentes. La plupart des femmes acceptaient l'avortement médicamenteux, et elles le demandaient de plus en plus. Des mécanismes doivent diffuser l'information parmi les professionnels, les agents de santé communautaire et les familles rurales. Les autorités de l'État doivent préparer un plan global pour inclure l'avortement médicamenteux dans le système de santé publique.

Resumen

La mifepristona y el misoprostol, fármacos utilizados para inducir el aborto, ahora están ampliamente disponibles en Tamil Nadu, en la India, y la práctica del aborto se está transformando. En este artículo se informa sobre las actitudes y prácticas actuales referentes al aborto con medicamentos entre prestadores calificados de servicios de aborto en una zona rural de Tamil Nadu. Se realizaron entrevistas con una muestra de 40 médicos, 15 boticarios, 10 enfermeras del poblado y 23 mujeres quienes recientemente habían tenido un aborto. Doce de los 37 médicos privados quienes prestaban servicios de aborto estaban efectuando el aborto con medicamentos en el 70-80% de sus pacientes, y 12 otros en una minoría. Once lo habían rechazado y aún usaban el legrado uterino instrumental (LUI), o D&C; dos nunca habían oído hablar al respecto. Varios médicos administraban el misoprostol para la dilatación cervical antes de efectuar el LUI. Algunos médicos y mujeres que expresaron inquietudes sobre el aborto incompleto y un sangrado abundante no sabían bien qué es un sangrado normal durante el aborto con medicamentos. Regímenes incorrectos para los abortos con medicamentos efectuados durante el segundo trimestre posiblemente fueron responsables de los casos de sangrado excesivo. En la mayoría de las boticas afirmaron que estaban vendiendo los comprimidos sólo con receta, pero los médicos informaron frecuentes ventas sin receta. El aborto con medicamentos pareció ser muy aceptado por la mayoría de las mujeres, quienes lo solicitaban cada vez más. Se necesitan mecanismos para compartir la información pertinente entre los profesionales, trabajadores comunitarios de salud y familias rurales. El gobierno estatal debería formular un plan integral para incorporar el aborto con medicamentos en el sistema de salud pública.

In 2001-02, during 15 months of intensive fieldwork in a rural district in Tamil Nadu in south India, the first author of this paper heard no mention of medical abortion despite having interviewed 97 women with recent abortions and a wide range of health care personnel.Citation1 There was no sign of it. Now, in 2005, mifepristone and misoprostol are available in many chemist shops in the area, and interviews with doctors and chemist shop personnel show that medical abortion is bringing about dramatic changes in abortion practices.

This paper documents this transformation in an economically marginal rural area in northern Tamil Nadu. The area lags behind much of the rest of the state in social indicators such as infant mortality and female literacy. Nonetheless, it is participating to some extent in India's economic development, in part because of its location near major transportation routes to metropolitan centres. The population of the district is about 2.8 million, in three small urban centres and widely scattered rural villages.

The choice of a low-income, peripheral rural area was deliberate. Geologists and other researchers often use the principle of “outcroppings” to examine the extent of spread of phenomena such as earthquakes from epicentres outwards to peripheral areas.Citation2 We hypothesised that the use of the abortion pill was gradually spreading throughout India via a well-established pharmaceutical distribution system, and that the processes of change in abortion patterns would be most fresh and visible in marginal rural areas, where the drugs had arrived only recently.

Since a liberal abortion law was passed in 1971, there has been a large increase in the number of practitioners and facilities providing abortion services, both certified and uncertified, and a considerable reduction in unqualified traditional providers.Citation1Citation3Citation4 The recent Abortion Assessment ProjectCitation5Citation6Citation7 in six states of India found that the majority of uncertified services were staffed by trained persons and were not substantially different from the certified facilities. In the non-certified, private facilities, 47% of 245 providers interviewed were obstetrician-gynaecologists.Citation7

Our previous research in Tamil Nadu found the pervasive use of D&C (dilatation and curettage) in both public and private facilities,Citation1 which has also been reported in nearly every study in India until very recently, with only 10-30% of providers reporting use of manual and electric vacuum aspiration. Citation5Citation6Citation7Citation8Citation9 Slightly more than half (57%) of the medically trained providers in a recent study in Rajasthan had heard of medical abortion, but only 16-18% had ever provided mifepristone and/or misoprostol for abortions.Citation8

Medical abortion has been widely available in Europe for well over a decade. In India there have been several major studies of the safety and acceptability of medical abortion in Maharashtra.Citation10Citation11Citation12 All those studies gave very positive results and showed that both rural and urban Indian women would be willing to use medical abortion. In 2002 the Drug Controller of India approved the manufacture and sale of mifepristone, and three Indian pharmaceutical companies were quick to begin marketing both mifepristone and misoprostol.Citation13Citation14

Methodology and participants

Data were gathered from April to June 2005. In-depth, open-ended interviews were carried out with purposive samples of 40 doctors (21 gynaecologists, 14 MBBS,Footnote* 3 surgeons, an anaesthesiologist, and a non-allopath), 15 chemist/medical shopFootnote* personnel, 10 village health nurses (VHNs) and 23 women who had recently had an abortion. The sample of 40 doctors included 37 abortion providers in private facilities and three in government services who were not doing abortions. The informants were selected using a non-random, snowball sampling technique in the main urban centres and market towns of the district. The doctors were representative of the geographic distribution, qualifications, age and years of experience of the more qualified abortion providers of the district. All but six of the doctors were women. This paper focuses mainly on adoption of medical abortion among MBBS and gynaecologically-trained private doctors (DGOs), as research in 2002 had shown that 75% of rural women in the district were going to private, qualified providers for abortions.Citation1

In interviews with the doctors, copies of the published papers on the medical abortion trials in MaharashtraCitation10Citation11Citation12 were shown and the doctors were asked to comment on the articles. In this way, the interview began on a scientific and intellectual plane, to encourage a broad perspective on the method before moving to questions of current, local practice. Questions centred first on doctors' opinions concerning the appropriateness and safety of medical abortion, after which details of the doctors' own experiences and provision of mifepristone and misoprostol were elicited. Interviews with the chemists focused on whether they were stocking and selling the two drugs. Interviews with the women focused on decision-making about seeking abortions, details of the abortion experience and any post-abortion problems.

Most of the interviews with the doctors were in English; with the others, a mixture of Tamil and English was used. Interviews with the VHNs and village women were in Tamil. The women who had had abortions were all from rural villages, up to two hours away from the urban centres. All interviews were carried out by the first author. Each person was told the purpose of the study, that participation was voluntary, that confidentiality and anonymity were assured and that they were not required to answer all the questions.

Medical abortion: widely, rapidly being adopted

As of April 2005, the tablets for medical abortion were available in almost all the chemist shops in the district. Misoprostol (costing about Rs.16 per tablet) is found even in the smaller shops, while the more expensive mifepristone (Rs.350 = US$8) is available mainly in the larger chemist shops and private hospitals in the municipal centres. Three pharmaceutical companies in India are manufacturing and distributing both kinds of tablets. Informants in the chemist shops said that most of the regular private providers of abortion services are now using them. Interviews with doctors and others at the various clinics largely confirmed this. Most doctors gave dates of first use in 2002 or 2003; others began using them in 2004.

Provider attitudes and practices: wide variations

The doctors differed considerably in their attitudes about the safety, efficacy and suitability of medical abortion. Of the 37 doctors providing abortion services, 12 were convinced that medical abortion was a safer, better procedure for many or most women; 12 others had adopted medical abortion for a selected minority of patients, but were cautious and sceptical about wider use; 11 largely rejected the method and two said they had never heard of it. Of the three doctors based in government services, one was enthusiastic about the potential importance of medical abortion, while the other two were opposed to it.

The differences among the doctors were related to differing views on the reliability of the method, the cost and women's ability to pay, and whether or not women would comply with the regimen. Among those doctors who were providing mifepristone and misoprostol, there were variations in the dosage and administration of the tablets, which seemed unrelated to the number of weeks of pregnancy. The case studies that follow illustrate these differences. (All names of persons and places are pseudonyms.)

Convinced medical abortion is a safer, better procedure for most women (12 doctors)

These providers reported that 70-80% of their terminations were medical abortions. Two of them said they provided medical abortion only and referred all others to other doctors. Seven of them were under 40 years of age; five were older, experienced practitioners. Several of them expressed the view that they must select patients for medical abortion very carefully, particularly with regard to the number of weeks of pregnancy. A majority of them were using ultrasound scanning for this reason.

Dr Kamakshi learned about medical abortion during her medical training and read about it in the medical journals. Her clinic is very neat and clean, with three beds, located in one of the main urban centres. She currently does approximately 75% medical abortions and 25% D&Cs. She accepts only cases that are below 12 weeks, and she does a physical examination and history to rule out any cardiac problems, anaemia, asthma and other contraindications to the drugs.Footnote* She also does a pelvic examination to check for ectopic pregnancy and an ultrasound to confirm the length of pregnancy. She has stocks of the tablets and supplies them to the women herself. She gave a cost estimate for medical abortion of Rs.684 (US$16.40), of which the largest items were Rs.330 for one mifepristone tablet and Rs.250 for the ultrasound. Her consultation fee was Rs.30 (US$0.72).

“If the pregnancy is over 63 days I conduct surgical abortion. If the date of last menstruation (LMP) is less than 63 days I give one mifepristone tablet 200mg and the patient has to swallow that tablet in my presence… The patient has to come back to my clinic 36 hours later to take 800mcg misoprostol. I insert four tablets in the vagina. I prefer the vaginal route because the action is effective and acts immediately on the uterus…When the patient visits after 15 days, I do one more ultrasound to confirm that there is no continuation of pregnancy… They [medical abortion patients] are poor and belong to a lower socio-economic category. They are illiterate, married, unmarried, working women and day labourers.”

Dr Divya is a senior gynaecologist with many years of experience. She has a small hospital with 15 beds in one of the urban centres. She said that nowadays she does about 80% medical abortions and only a few D&Cs. She allows patients to choose which procedure they prefer.

“These little pills are great and it is a boon to the women and the service provider… I am getting fantastic results.”

Providing medical abortion for a selected minority of patients (12 doctors)

Dr Ramani is young, and only recently completed her gynaecological training, where information about medical abortion was introduced and also came up in informal discussions with colleagues. Her clinic was not large, and she appeared to be quite cautious about doing medical abortion, as she believed that only the better informed, somewhat wealthier patients could afford the time and extra cost. She was doing about 25% medical abortions and 75% D&Cs.

For her medical abortion patients, she counselled them and provided the WHO-recommended regimen of 200mg mifepristone followed two days later by 400mcg misoprostol. She was taking only women whose LMP was 56 days or less. Like the other doctors she emphasised the need to screen out cases with cardiac problems, anaemia, diabetes and other contraindications. In addition, she put strong emphasis on information about the patient's access to transport.

“…I find out where the patient comes from, how far, distance, transportation, whether remote and inaccessible or semi-urban. I must know all this background information because they have to visit my clinic a minimum of three times. The distance and transportation are extremely important.”

Her medical abortion patients have included several unmarried young women, who she said were particularly afraid of D&C and were able to arrange the money for a medical abortion.

Dr Sita is an older, experienced gynaecologist with 30 years of experience in the area. Her small, 10-bed clinic-hospital is in a sub-district town about one hour from the urban centres. She had begun providing medical abortion two years before the interview, but with mixed success. Now she spoke of providing four different procedures, depending on the woman's situation: 1) regular D&C plus manual vacuum aspiration, 2) D&C preceded by misoprostol, 3) medical abortion using mifepristone and misoprostol, and 4) for cases over 12 weeks in-patient use of manual vacuum aspiration. Her view was that D&C preceded by misoprostol was the most cost-effective for poor, rural women. Earlier she had tried using the mifepristone-misoprostol combination with many rural women, but found that it was not always effective and the added costs of completing the abortion surgically were beyond the women's means. For the few women who could afford what she called the “full” medical abortion regimen, she was giving three 200mg mifepristone tablets (600mg), which the women were told to take at home, followed two days later by two 200mcg misoprostol tablets (400mcg), after which they should come back to her in ten days to check if the abortion was complete.

Largely rejected the mifepristone-misoprostol regimen (11 doctors)

Eleven doctors were not using or prescribing either mifepristone or misoprostol, and were still doing D&C with sharp curettage.

Dr Sunil is a surgeon and his wife an MBBS qualified doctor. They have been practising in a rural sub-district town for about 15 years, where they operate a small clinic-hospital with about 14 beds. He first heard of medical abortion in an educational meeting of the Indian Medical Association. He and his wife are not interested in doing abortions, though they do get some cases, and they also handle post-abortion complications. When asked about medical abortion, he said they did only D&C because women came to them too late for a medical abortion.

Dr Pavitra is a surgeon with many years' experience with D&C in her large and well-equipped hospital. As she has large patient loads, she prefers D&C because it is “quicker and easier” . Her husband is a gynaecologist. She said that he had tried medical abortion three months earlier, and the patients had had very serious bleeding problems.

“I am nervous and not confident about using this method. I am not doing medical abortion because it is time consuming and the procedure is costly. Follow-up care is exceedingly difficult. In the last six months… I have done roughly 400 D&Cs under general anaesthesia.”

Dr Sowmya is a senior obstetrician-gynaecologist in one of the urban areas:

“I am against medical abortion and I am not interested in doing abortion using those pills. The other doctor told you that I am old and a senior obstetrician-gynaecologist, but I am also conservative. I am doing strictly D&C and I do not use all those pills and tablets with my patients. I have never tried these methods at all, although I have heard about those abortion pills through medical representatives.”

Usage of medical abortion drugs: a wide variety

Among the doctors providing or prescribing mifepristone and misoprostol, the following usages emerged, some of which are up to nine weeks of pregnancy and others later than that:

A combination of mifepristone and misoprostol, with varying amounts of each drugFootnote*

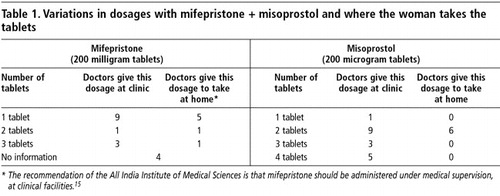

Some of the doctors admitted they were still experimenting with different regimens for medical abortion. In two cases, the doctors asked the researcher for advice and further information about the procedures. The varied dosage and administration of the two drugs and the number of doctors reporting the practice are shown in Table 1. These were reported to be the doctors' usual practice up to 49 or 56 days of pregnancy. Four doctors reported giving three 200mg mifepristone tablets (600mg), which was the standard dosage when the first trials took place, including in India. But the most used dosage was 200mg, which is now considered to be best practice because it works as well as 600mg and is less expensive. Administration of mifepristone took place either under supervision at the clinic or was taken at home. Similarly, some prescribed the misoprostol to be taken at home two days after the mifepristone, while others insisted that the woman come back to the clinic, and in many cases they inserted the misoprostol tablets vaginally themselves. Misoprostol dosage varied from one to four 200mcg tablets.

Misoprostol to facilitate cervical dilatation followed by D&C

Of the 37 informants who were currently providing abortions, 18 said they were using misoprostol followed by D&C (including eight of those who were also providing medical abortion), particularly for pregnancies beyond 63 days LMP. First, misoprostol is inserted vaginally, then the woman has to wait several hours, after which the doctor performs “soft curettage” . This was not considered medical abortion because the misoprostol was not given a chance to bring about the abortion on its own.

“Soft curettage” , according to Dr K, a gynaecologist, is when they use misoprostol first and then use the blunt edge of the curette with perhaps only one dilator and access the intrauterine cavity with the dilator and an ovum forceps. Without misoprostol, the gynaecologists said they used from 4 to 16 dilators to open the cervix for curettage. One described D&C on its own as needing to be “forceful” , in contrast to “soft curettage” .

“If misoprostol tablets are inserted four hours before the surgical abortion we can avoid forceful curettage. The system is set and is ready and therefore it is much easier to do curettage.” (Dr V)

“For those women who are above 12 weeks I insert two misoprostol tablets vaginally and wait for 5 or 6 hours. It is expected that the cervical region will be ripened and I do soft curettage… There is no need for [dilators].” (Dr M)

Misoprostol alone, inserted vaginally, followed by soft curettage or manual vacuum aspiration (MVA) if the abortion was incomplete when the woman returned a few days later

This usage was reported by only one doctor, but several doctors mentioned the use of MVA. Use of MVA was said to have been spreading in the area in recent times, and had now taken on a somewhat changed role in that it was being used for management of incomplete medical abortions.Footnote*

Mifepristone alone, without misoprostol

One chemist shop proprietor reported that he recommended this regimen, and one woman reported this to be the procedure in her recent abortion.

Use of an injectable prostaglandin

To add further to the complicated variations, several practitioners reported using Prostadin (carboprost) injections. In several cases they used it to cause contractions, but two individuals mentioned injecting this drug to stop excessive bleeding.

The role of the chemist shops and their staff

Some of the doctors sent patients with a prescription to buy the tablets from a chemist shop. Others, especially at larger clinics and hospitals, had their own stocks. The 15 chemist shop informants were mainly working at the larger, well-stocked establishments. Some of the larger shops also supplied mifepristone and misoprostol to smaller shops as well as to clinics and hospitals. Most of the chemist shop proprietors told us that they sold the abortion tablets only by prescription, but three admitted to some over-the-counter sales. Sale of the tablets without prescription by chemist shops was widely reported by the doctors, however, and several of them were vehement about the need to curb this practice. It was reported by several doctors that criminal charges had been filed against one of the chemist shops for over-the-counter sale of the medicines.

Doctors' attitudes about rural women and their suitability for medical abortion

We found wide variations in the doctors' beliefs about whether their women patients could handle medical abortion, and the perceived difficulties in getting rural working women to return for follow-up. Several gynaecologists and MBBS doctors expressed opinions similar to this:

“…this method is not appropriate for rural women. They are less knowledgeable, lack awareness and are not cooperative with the doctors. This method might be more suitable for educated urban people.” (Dr Minusha)

Doctors who were positive about the benefits of medical abortion also seemed more positive about the level of awareness and cooperativeness of rural women, however.

“In my experience, women are opting for medical abortion and there is a rising trend for medical abortion. Women come and demand ‘the new tablet for having an abortion’. They have knowledge about the new pills…” (Dr Lalitha)

“It is spreading…Rural women come and ask me: ‘Somebody in my village told me that you are doing abortion using only injections and tablets. I want to have injection and tablet…We cannot underestimate their knowledge and awareness… these rural women are extremely smart… I put before them both surgical and medical [options]…and I give them time to decide.” (Dr Divya)

Limited awareness among women and village health nurses

The interviews with women in the villages showed that information about medical abortion was just beginning to reach some of them. Of the 23 women, who had all recently had abortions, six had had D&Cs, 13 had had misoprostol followed by D&C, three had had mifepristone-misoprostol and one had had mifepristone only.

In April 2005, when Sandhya from a small remote village was describing her recent experience with “tablet abortion” , several other women joined the conversation and eagerly pressed her for information, as they had never heard about it. Some thought this was not “real abortion” , which as they understood it was done with instruments. It would appear that in many areas women were hearing about the new pills for the first time around April-May 2005, whereas in villages closer to the urban centres, some informants said the knowledge was already widespread.

Medical abortion appeared to be quite acceptable conceptually to the rural women, and three or four doctors reported that women had requested “abortion with tablets” . In the past, many women have first tried to “bring down their periods” using various tablets bought at chemist shops, so the concept is familiar to them.Citation17 Several doctors reported that young unmarried women are especially fearful of D&C, and some married women in our previous research had expressed negative feelings about the pain and invasiveness of surgical abortion.

The VHNs interviewed said they knew nothing about medical abortion. They seemed vaguely aware that something new was going on, but they had not been instructed about the new technology and had apparently not asked the women about their recent abortion experiences, even though they had had to follow up on some cases of what they described as excessive bleeding.

Concern and uncertainty about whether bleeding is normal or not

Previous research on the safety and acceptability of medical abortion among rural Indian women reported a mean of 7.4 days of bleeding after misoprostol use,Citation18 which means about half of the women experience eight days or more of bleeding. Most of the doctors, particularly those who were sceptical or outright opposed to medical abortion, believed post-abortion bleeding to be the most serious problem with medical abortion. Several women also reported having had “excessive bleeding” , and it appears that they had not received adequate counselling as to what was and was not “normal” . Unfortunately, it was difficult to obtain a clear definition or description of what either the doctors or the women meant by “excessive bleeding” and therefore also to be able to assess the actual extent of this problem.

Some of the doctors who were concerned about high rates of incomplete abortion did not seem to have a clear idea of what normal bleeding with medical abortion was, and also seemed to be unaware of the studies in Maharashtra, in which rates of incomplete abortion were 5% or less.Citation10Citation11Citation12 When pregnancies are terminated using D&C or MVA, women are generally not aware of the amount of blood that is removed during the process, so they need to be told that this blood comes out naturally with medical abortion, most heavily when the actual miscarriage takes place (usually within 24 hours of using misoprostol) and then less heavily for up to several weeks. For example, three of the women interviewed who had had a medical abortion reported bleeding for 15 to 20 days and in cases like this both doctors and patients may have been unnecessarily alarmed.

On the other hand, excessive bleeding due to incomplete abortion is serious. Two of the providers who had stopped using the new method said it was because of excessive bleeding. Several cases of excessive bleeding were reported by the doctors, but some of them were second trimester pregnancies that should have been handled as in-patient procedures, probably using a more effective regimen. In four such cases reported to us, women had to be hospitalised for blood transfusions.

“According to Dr. Kasturi, 'most of the medical abortions are incomplete and need to be followed by curettage'. In addition she mentioned that the bleeding is very high with medical abortion compared to surgical. While describing the excess bleeding she said that in recent weeks there were three women who were referred to her from Kalapuri. These women had gone for medical abortions and had ended up with incomplete abortions. When they came to her, they were in bad shape, she said. All these women were given blood transfusions immediately in order to avoid further emergency and fatality.” (Excerpt from field notes)

On the other hand, it is notable that despite all these concerns, no recent cases of post-abortion death were reported in the region.

Different perceptions of bleeding: two examples

The following two cases show the difference that accurate information on the part of doctors and good counselling of women can make as regards concerns and interventions to address the bleeding that is induced as part of the medical abortion process:

Tara told the interviewer that she was a little over 90 days pregnant when she and her husband decided to terminate the pregnancy. She went to an MBBS practitioner whom our VHN informants had previously identified as “low quality and unsafe” .Citation1 Tara said that two days after the vaginal insertion of the tablets she was on a bus and began to have severe bleeding. She was taken to a doctor, who was prepared to do D&C but Tara decided to go home instead. The bleeding continued, and she was able to go to a hospital two days later, after she and her husband marshalled sufficient money for hospital admission. She immediately received a blood transfusion, and the gynaecologist at the hospital carried out a D&C to remove any remaining products. This case appears to have involved inadequate counselling, possibly the wrong medical abortion regimen and possibly also an unnecessary D&C.

Bindhu said she was slightly more than seven weeks pregnant when the family decided that she should get an abortion. Her VHN suggested that she go to Dr M, a gynaecologist with a well-equipped hospital. Bindhu still had the empty package that had contained a mifepristone tablet, with the price of R.375 clearly marked. She said she had been instructed to take the tablet at home, and following the doctor's instructions, she returned to the clinic two days later, where the gynaecologist inserted some tablets vaginally and told her to go home. That same evening there was heavy bleeding, which she said lasted for 7-8 days. When she went back to the clinic she was told that abortion was complete and “everything had come out” . The total charge was Rs.450; the doctor did not charge anything for the follow-up visit. Bindhu did not seem to be overly disturbed by the extent of the bleeding, perhaps because the gynaecologist had given her clear information about what to expect.

Despite the extent of bleeding, the great majority of women in the Indian studies have reported satisfaction with the procedure. In a recent Parivar Seva Sanstha study, for example, 70% of the women were highly satisfied.Citation19 Apparently the number of days of bleeding is not seen as a serious deterrent by most women.

Medical abortion in government facilities: a note

We interviewed three doctors based in government facilities but none of them was doing abortions and we have not yet studied the current practices in government abortion facilities. The very preliminary picture that has emerged from interviews with these three doctors is that government facilities locally were not using the mifepristone-misoprostol regimen, but that there was considerable use of misoprostol in connection with D&C procedures. Although some doctors in health centres were quite adamant that medical abortion was not suited for use in the situation in government facilities, two of the government doctors were strong advocates of medical abortion, saying it should be widely adopted in the primary health centres and government hospitals. One doctor in a government hospital asked plaintively: “What am I to do? There has been no government order or circular about medical abortion.”

Discussion

The major obstacles to further expansion of medical abortion use in the area appear to be doctors' concerns and uncertainties about when post-abortion bleeding is a complication and when it is not, plus the real or perceived difficulties in getting rural working women to return for post-abortion follow-up. Many of the “problems” the providers report concerning medical abortion are related to the difficulties rural women face accessing the mainly urban-based services. The differences between doctors in their management of medical abortion seem to reflect differences in their level of knowledge and confidence. Doctors who were the most positive and confident about medical abortion also reported very few post-abortion problems.

Medical abortion requires more counselling and communication between providers and abortion-seekers than has been considered necessary with surgical abortion. This is because the method is new and takes place entirely in the woman's body rather than through a surgical procedure where the provider is in control and the “cooperation” or “compliance” of the woman is not an issue.

Medical abortion has been somewhat more costly so far because of the cost of mifepristone and in many cases the ultrasound scan, yet many women still expressed a preference for the non-invasive procedure. Doctors report that rural women are becoming more knowledgeable and are asking more questions about abortion procedures. The changes now taking place appear to be giving women more choice of method, and more openings for negotiation and self-assertion in interactions with doctors.

Recommendations

Private practitioners, through their medical associations and other means, should develop mechanisms for sharing and increasing their knowledge of “best practices” of medical abortion, including management of post-abortion bleeding. Individual experimentation with both dosage and administration of the tablets, as shown in our findings, appeared to be medically unsound as they were not evidence-based.

The reported lack of policy and guidelines regarding provision of medical abortion in government facilities should be rectified through a consultative procedure by the state government that includes providers and women.

Regardless of what policies are put in place at the various levels of government facilities, community health workers (VHNs and male workers) should be given training and information so that they can educate villagers in their areas about the options now available for pregnancy termination and the importance of early decision-making. VHNs especially need to be alert to the possibility of serious bleeding cases brought about particularly by inappropriate regimens and poor or unsupervised use of the abortion tablets. Ways of dealing with serious bleeding cases need to be discussed in PHCs and community health workers' meetings.

Informational materials should be developed for educating practitioners, chemist shop staff and communities about all aspects of abortion services, with special attention to medical abortion.

The advent of widespread availability of mifepristone and misoprostol has brought about a general transformation of abortion practices, particularly among qualified gynaecologists and MBBS doctors who are responsible for the majority of pregnancy terminations. The situation of ongoing change provides an opening for greatly expanded dialogue between private and governmental health personnel concerning the overall increased use of medical abortion, more appropriate use of MVA and drastic reduction in the use of D&C.

Notes

1 MBBS is Medical Bachelor/Bachelor of Surgery, the usual graduating degree in Indian medical colleges.

* The shops range from large chemist shops staffed by trained pharmacists, to small shops selling medicines and other preparations without formally trained personnel. Hereafter we will refer to all of them as chemist shops for convenience.

* The doctors' statements about contraindications generally corresponded to those listed in the guidelines for medical abortion by the All India Institute of Medical Sciences.Citation15

* The regimen included on the WHO Essential Medicines list since July 2005 is 200mg mifepristone followed 36-48 hours later by 800mcg misoprostol vaginally up to nine weeks (63 days) of pregnancy.Citation16

* One doctor also mentioned the use of MVA prior to D&C: “When we do the D&C, lots of fluid will be collected around the fetus. That fluid will be sucked out with the use of that apparatus. When the suction is used, the pregnancy contents will all be sucked out along with the fluid. The remaining products will be removed using the curette.”

References

- L Ramachandar, PJ Pelto. Abortion providers and safety of abortion: a community-based study in a rural district of Tamil Nadu, India. Reproductive Health Matters. 12(24S): 2004; 1–9.

- EJ Webb, DT Campbell, RD Schwartz. Unobtrusive Measures: Non-Reactive Research in the Social Sciences. 1966; Rand-McNally: Chicago.

- B Ganatra. Abortion research in India: what we know and what we need to know. R Ramasubban, S Jejeebhoy. Women's Reproductive Health in India. 2000; Rawat Publications: New Delhi, 186–235.

- L Ramachandar, PJ Pelto. The role of village health nurses in mediating abortions in rural Tamil Nadu, India. Reproductive Health Matters. 10(19): 2002; 64–75.

- Abortion Assessment Project - India. Key Findings. February 2004. At: . <www.cehat.org/publications>. Accessed June 2004.

- Abortion Assessment Project - India. Synthesis of multicentric facility study. At: . <www.cehat.org/publications>. Accessed June 2004.

- S Barge, WU Khan, S Narvekar. Accessibility and utilization (Special issue on abortion). Seminar. 2003; (December).532.

- S Barge, H Bracken, B Elul. Formal and Informal Abortion Services in Rajasthan, India: Results of a Situation Analysis. 2004; Population Council: New Delhi.

- R Chhabra, SC Nuna. Abortion in India: An Overview. 1994; Ford Foundation: New Delhi.

- B Winikoff, I Sivin, K Coyaji. Safety, efficacy and acceptability of medical abortion in China, Cuba and India: a comparative trial of mifepristone-misoprostol versus surgical abortion. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 176(2): 1997; 431–437.

- K Coyaji. Early medical abortion in India: three studies and their implications for abortion services. JAMWA. 55(Suppl.): 2000; 191–194.

- K Coyaji, B Elul, U Krishna. Mifepristone-misoprostol abortion: a trial in rural and urban Maharashtra, India. Contraception. 66(2): 2002; 33–40.

- Abortion pill to be introduced in Family Planning Programme. The Hindu. 16 October 2002.

- R Sundar. Abortion Costs and Financing: A Review. Abortion Assessment Project - India. 2003; Centre for Enquiry into Health and Allied Themes (CEHAT): New Delhi.

- S Mittal. Guidelines for Medical Abortion in India. All India Institute of Medical Sciences. At: <www.aims.ac.in/aiims/events/gynaewebsite/. August 2005>. Accessed.

- World Health Organization. Essential Medicines Library WHO model list of Essential Medicines. At: <www.who.int/medicines/organization/par/edl/eml.shtml. July 2005>. Accessed.

- Ramachandar L. Decision-making and women's empowerment: abortion in a South Indian community. Doctoral dissertation. University of Melbourne: Australia. 2004.

- K Coyaji. Medical Abortion - Rural Experience. Consortium on National Consensus for Medical Abortion in India 2003. At: <www.aiims.ac.in/aiims/events/gynaewebsite/ma_finalsite. May 2005 >. Accessed.

- A Banerjee. Medical Abortion: Experience of PSS [Parivar Seva Sanstha]. Consortium on National Consensus for Medical Abortion in India 2003. At <www.aiims.ac.in/aiims/events/gynaewebsite/ma_finalsite. May 2005>. Accessed.