Abstract

In Latin America, where abortion is almost universally legally restricted, medical abortion, especially with misoprostol alone, is increasingly being used, often with the tablets obtained from a pharmacy. We carried out in-depth interviews with 49 women who had had a medical abortion under clinical supervision in rural and urban settings in Mexico, Colombia, Ecuador and Peru, who were recruited through clinicians providing abortions. The women often chose medical abortion to avoid a surgical abortion; they thought medical abortion was less painful, easier or simpler, safer or less risky. They commonly described it as a natural process of regulating their period. The fact that it was less expensive also influenced their decision. Some, who experienced a lot of pain, heavy bleeding or a failed procedure requiring surgical back-up, tended to be more negative about it. Regardless of legal restrictions, medical abortion was being provided safely in these settings and women found the method acceptable. Where feasible, it should be made available but cost should not have to be women's primary reason for choosing it. Psychosocial support during abortion is critical, especially for those who are more vulnerable because they see abortion as a sin, who are young or poor, who have limited knowledge about their bodies, whose partners are not supportive or who became pregnant through sexual violence.

Résumé

En Amérique latine, oú l'accès à l'avortement est presque partout restreint par la loi, l'avortement médicamenteux, particulièrement avec le seul misoprostol, est de plus en plus utilisé, souvent avec des comprimés obtenus dans une pharmacie. Nous avons interrogé 49 femmes ayant subi un avortement médicamenteux sous surveillance clinique dans des environnements ruraux et urbains au Mexique, en Colombie, en Équateur et au Pérou, sur le conseil de cliniciens pratiquant les avortements. Les femmes avaient souvent choisi l'avortement médicamenteux pour éviter l'avortement chirurgical ; elles pensaient que cette méthode était moins douloureuse, plus facile, plus sûre ou moins risquée. Elles la décrivaient comme un processus naturel de régulation des menstruations. Son moindre coût avait aussi influencé leur décision. Certaines, qui avaient eu de fortes douleurs, des saignements prolongés ou qui avaient dû compléter l'avortement avec une intervention chirurgicale, étaient plus négatives. Sans se soucier de restrictions légales, l'avortement médicamenteux était pratiqué sans risque et dans ces conditions, les femmes pensaient que la méthode était acceptable. Quand c'est possible, il devrait être proposé, mais le coût ne devrait pas être la première raison du choix des femmes. Le soutien psychosocial est essentiel, particulièrement pour celles qui sont plus vulnérables parce qu'elles considèrent l'avortement comme un péché, qui sont jeunes ou pauvres, connaissent mal leur corps, dont les partenaires ne les épaulent pas ou qui sont enceintes par suite de violences sexuelles.

Resumen

En Latinoamérica, donde el aborto es restringido casi universalmente por la ley, el aborto con medicamentos, especialmente con misoprostol solo, se utiliza cada vez más, a menudo con comprimidos obtenidos de una farmacia. Realizamos entrevistas a profundidad con 49 mujeres que habían tenido un aborto con medicamentos bajo supervisión clínica en zonas rurales y urbanas de México, Colombia, Ecuador y Perú, quienes fueron reclutadas por profesionales clínicos que prestaban servicios de aborto. A fin de evitar un aborto quirúrgico, muchas mujeres eligieron el aborto con medicamentos, pues lo consideraron menos doloroso, más fácil o sencillo, más seguro o menos arriesgado. Comúnmente lo describieron como un proceso natural de regulación menstrual. El hecho de que era menos costoso también influyó en su decisión. Algunas, que experimentaron mucho dolor, sangrado abundante o un procedimiento fallido, que requirió respaldo quirúrgico, eran más negativas al respecto. Sin considerar restricciones de ley, el aborto con medicamentos estaba siendo efectuado de manera segura y en tales circunstancias las mujeres lo encontraron aceptable. Donde sea factible, debe hacerse disponible, pero el costo no debe ser la razón principal para su elección. El apoyo psicosocial durante el aborto es fundamental, especialmente para las mujeres que son más vulnerables porque ven al aborto como un pecado, son jóvenes o pobres, tienen poco conocimiento de su cuerpo, sus parejas no las apoyan, o quedaron embarazadas a causa de violencia sexual.

Unsafe abortion remains a serious public health problem in Latin America. Although abortion is almost universally legally restricted, in each of the countries abortion services are widely available, especially in urban areas, ranging from safe (and generally more expensive) to unsafe, with rural and poor women disproportionately affected.Citation1 The rate of unsafe abortions is about 29 per 1000 women of reproductive age.Citation2 In Ecuador, Peru, Mexico and Colombia, induced abortion is defined as a crime in the penal code, with few exceptions.Citation3 Estimates for 1995-2000 indicate that in Ecuador 18% of maternal deaths are due to unsafe abortion, in Peru 16%, Mexico 23% and Colombia 28%.Citation4 Little effort has been made to improve access to safe abortion services in these countries, but post-abortion care programmes to treat abortion complications have been promoted throughout the region.Citation5

Interest in the use of medical abortion has been growing during the past decade throughout Latin America,Footnote* using mainly misoprostol alone. In some places, methotrexate plus misoprostol is used, mainly under clinical supervision. Compared to other techniques used to induce abortions clandestinely, medical methods appear to be safer and associated with fewer complications.Citation7Citation8Citation9 As a result, mortality from unsafe abortions may have decreased in the region. This has been seen in several countries, including Peru and Brazil,Citation7Citation9Citation10 and is suspected more widely by public health experts. A recent review of death certificates in one urban area in Mexico, for example, found no deaths related to first trimester abortion, perhaps in part because of the increasing use of medical methods.Citation11

Evidence in the region about women's use of medical abortion and its impact on their health and lives is generally anecdotal, and only a few studies have documented their experiences. Studies from Brazil, Honduras, Mexico, Nicaragua, Peru and Puerto Rico illustrate that women obtain misoprostol either from pharmacies without a prescription or from physicians, who either prescribe or dispense it directly, Citation9Citation10Citation12Citation13Citation14Citation15 and a recent report of the safe and effective use of misoprostol alone in a Latin American clinic found that women were satisfied using misoprostol alone, would use it again if they needed to terminate another pregnancy and would recommend it to a friend.Citation10

Because an in-depth understanding of women's experiences with medical abortion in different settings in the region would help providers and women to use it more safely and effectively, we carried out a qualitative study to collect information about women's experiences using misoprostol or methotrexate plus misoprostol under clinical supervision in Mexico, Colombia, Ecuador and Peru. This study does not capture the experiences of women who do not have clinical support and who use misoprostol on their own or with the help of partners, friends or family, probably the most common mode of use of medical abortion in the region. However, our aim in this study was to help to guide efforts to meet women's needs in a safe, comprehensive manner, which influenced our decision to follow a protocol that ensured that women had ongoing support during their abortions.

Methods

In all four countries, we contacted clinicians who generally provide both surgical and medical abortion services and asked them to identify and invite women to participate in this study. Between October 2003 and May 2004, they invited to participate all the women who were at least 18 years old and who attended for follow-up in their clinics after a medical abortion. Because of the legal restrictions in each of the countries, we do not provide information here about the providers, in order to protect them and the women they serve. In each case, the women had used either vaginal misoprostol alone up to a maximum of ten weeks of pregnancy LMP or intramuscular methotrexate followed by misoprostol up to eight weeks LMP. Forty-nine women agreed to participate.

We conducted in-depth interviews with them following a guide that led the women to reconstruct a narrative based on three time periods: the decision to abort and the method chosen, the experience of medical abortion and the overall assessment afterwards. Each interview lasted between one and two hours and was tape-recorded and then transcribed. Interviews were coded and analysed using the Atlas Ti 5.0 software (Scientific Software Development, Berlin). To ensure consistency in the coding, each coded interview was verified by a second independent researcher. All interviews were conducted in Spanish, and the analysis was performed using the original Spanish text. The representative quotations cited here were translated into English, and participants' names were changed to protect their privacy. This study was approved through the Population Council's ethical review process, and all participants gave consent to participate and have the interview recorded.

Participants

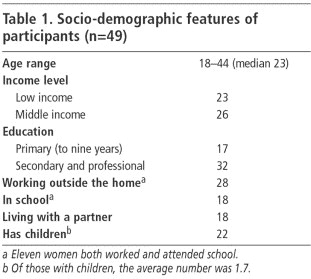

Participants came from an urban setting in Colombia (11), an urban (9) and a rural (6) setting in Mexico, an urban setting in Peru (12) and an urban coastal (5) and urban Andean (6) setting in Ecuador. Those referred by the same clinician tended to come from the same socio-economic group because of the location of the clinician, and were not necessarily representative of all women having abortions (Table 1). Participants from Peru, Ecuador and the rural area of Mexico predominantly had limited economic resources, while those from urban Mexico and Colombia were more likely to be middle class and with a higher level of schooling. Their ages ranged from 18 to 44, but most were in their mid-20s.

Twenty-two of the women had never used a modern method of contraception, 12 said they were not using a method at the time they got pregnant, 12 said the method they were using had failed and three were victims of sexual violence. Several women mentioned that their partners had said they would take responsibility for preventing pregnancy, but in the end either refused to use condoms consistently, failed to withdraw prior to ejaculation or had reported using non-existent male methods.

In general, except for participants from the urban area in Mexico, who reported emergency contraceptive use, the women seemed either ill-informed about the need to use contraception consistently or had inadequately incorporated it into their lives.Citation16Citation17 Studies in Colombia and Mexico have found that lack of knowledge of reproductive physiology, lack of partner and social support to use contraception, negative perceptions of modern methods, preference for less effective methods, incorrect method use and wishful thinking that pregnancy won't happen all contribute to unwanted pregnancy.Citation17Citation18 The role of sexual violence has also been taken into account only in recent years.

Of the 49 women, 37 had a successful medical abortion while 12 women underwent a surgical procedure after a failed medical abortion. Thirty-eight women used misoprostol alone, of whom 30 had successful procedures, and 11 women used methotrexate plus misoprostol, of whom 7 had successful procedures. The median duration of pregnancy since the last menstrual period at the time of the abortion was seven weeks. Because we did not review the women's medical records, we cannot differentiate the reasons for method failure, i.e. ongoing pregnancy, incomplete abortion or prolonged bleeding. The proportion of participants who had surgical follow-up was higher than expected, compared to the published studies, but this may be because women with complete abortions were less likely to attend for follow-up, or because providers acted cautiously, given the clandestine situation, or because women may not have inserted the tablets at home as directed.

Deciding to have an abortion

Fourteen women reported previous abortions, either induced or spontaneous, of whom three reported previous medical abortions. The women from urban Mexico described the decision to have an abortion in terms of the importance of their own personal life plans. Women from the other settings talked about the important role of their family, partner and children in their decision. Twenty-eight women said their partners participated in the decision. Several participants mentioned financial reasons, and a few also had medical reasons. Thirty-two participants expressed a desire to become pregnant in the future, 15 had had their desired number of children and two did not want to become mothers. Women who were already mothers spoke about devoting their resources to their existing children, while several young women without children hoped to have a family in future when the time was right.

“My mother is a single mother, and I didn't want to repeat history… This isn't about marriage, it's not that. No, I want to finish school and I want to give my child the best… I don't want to feel frustrated that I gave up my career to have a baby, and then maybe I'd end up later focusing all that anger on my child.” (Sara, age 19, university student, no children, Peru)

The women from Peru and Ecuador tended to express stronger feelings of guilt and generally did not mention positive aspects of their decision to abort.Citation16 The Mexican and Colombian women commonly discussed abortion as something “necessary for women” or a woman's right to choose when faced with an undesired pregnancy. These perspectives enabled them to understand the need for abortion in the context of their lives.Citation17Citation18 Although they still expressed feelings of guilt, they tended not to blame themselves but felt they had made the best decision possible given the limited choices available to them.

“I didn't feel so guilty at the time [of the abortion]. Now I feel guilty, yes, because I ended a life and that comes with other moral stuff. But if I think about it in terms of the person who was going to be the father of my child, I feel fine. It was the best decision I could make.” (Soledad, age 30, psychologist, Colombia)

Deciding to have a medical abortion

Fifteen women reported some knowledge of medical abortion prior to coming to the provider, although their familiarity with the method was generally superficial. Three women said they had taken misoprostol on their own and one had used an injection obtained from a pharmacy to induce an abortion, but these attempts were all unsuccessful. They had then approached a provider.

Many of the women said they had opted for medical abortion in order not to have a surgical abortion. Those from Colombia, Ecuador and Peru chose it largely because they thought it would be less painful than surgical abortion. Those from Ecuador and Peru also frequently thought it was less risky or dangerous than surgical abortion. When asked if she would have had a surgical abortion if medical abortion were not available, one said:

“No. For me, it would have been very difficult. There's less trauma [with medical abortion]…And then there's everything they say… that you can die in surgery… everything that's in the media.” (Margarita, age 28, working student, Colombia)

Participants from all four countries said they chose medical abortion because it seemed easier, more natural, less invasive and offered more privacy. In addition, it allowed them to experience the abortion at home with their partner, friend or family. In five cases, the provider had recommended the method, which was also influential. In many settings, the cost of medical abortion with provider involvement, US$60-130, was less than for surgical abortion, which was important for many of them. In contrast, the cost of the misoprostol tablets, purchased at a pharmacy rather than through a provider, was US$15-78, and differed by place of purchase.

The medical abortion experience

Prior to abortion, the women underwent counselling about the abortion and method options, followed by a physical examination and confirmation of the duration of pregnancy, which in some settings included an ultrasound. Women who used misoprostol alone received two or three doses of 800 mcg each (four 200 mcg tablets), 24 hours apart, placed high in the vagina. Women who received methotrexate were given an injection of 50 mg/m2, followed three to seven days later by misoprostol 800 mcg administered vaginally (except one woman, who received the same dose of misoprostol buccally) and in most cases the misoprostol dose was repeated once 24 hours later. For 23 of the women, the provider inserted all the misoprostol tablets, and women returned for each dose, while 18 women inserted the tablets at home themselves. In seven cases, the provider inserted the first dose of misoprostol and then the women inserted the subsequent doses at home. Most women said the insertion was easy, similar to or easier than inserting a vaginal suppository or tampon. One woman had her partner insert the tablets, both to include him in the process and because she felt more confident he would be able to place them appropriately.

After inserting the tablets, 14 women continued with their routine of work or studying, while the remainder rested or tried to relax. Some women went to other people's homes or out with friends. Several continued to do household chores. They frequently lay down. Some watched television; others walked, hoping to speed up the process (which does not work). Twenty-eight women reported there were other people around during the abortion process, in some cases family members who were not aware of the abortion. Some felt relieved upon seeing blood and took this as a sign that the medication was working. Consistent with studies that suggest most women can correctly determine if medical abortion is successful,Citation19Citation20 most women described the passage of blood clots, sometimes with tissue or membranes, as the moment when they believed the pregnancy ended.

Cramps were the most common side effect, reported by 46 women, and were described as very strong by 17. Women reported that the most intense pain lasted between two and three hours. Many reported using pain medication, which was commonly recommended by providers, but we did not routinely ask about analgesic use. All women with a successful medical abortion experienced some vaginal bleeding, which in general lasted approximately nine days. Eight women reported intense bleeding during the expulsion. Of these, some reported being unprepared for the quantity of bleeding and were fearful of haemorrhaging at home in front of their families.

“The bleeding started like a period, and then it came heavy…At first I thought the bleeding was going to be like a period, just a little, but the next day when I sat on the toilet, the blood was coming out like water.” (Alba, age 25, rural migrant, Peru)

In each of these cases, the bleeding either spontaneously diminished or the woman went back to the provider for treatment; none required a blood transfusion. Side effects reported were chills (9), vomiting (6), abdominal pain (5), diarrhoea (5) and dizziness (4). Of the 17 women who experienced severe pain, 11 had never given birth, an association that has been previously demonstrated.Citation21

Women described a range of emotions during the process. Of the 37 who had a complete abortion, 11 were relaxed during the process, of whom seven had previously given birth, while the remaining 26 felt worried or anxious. Of eight women who found the experience emotionally draining, six had not previously given birth. We believe that the women who had given birth before were less anxious about the pain and bleeding associated with medical abortion, and may have felt less conflicted about the abortion.

“What did I feel? I felt at peace. At peace in a way and free of feelings of guilt or anything like that. I felt at peace because I knew that what I did I did in good conscience and I did well.” (Margarita, age 28, one daughter, Colombia)

“I started feeling a little bad, I felt like I shouldn't be doing this, but then this feeling passed because I went to church and I prayed very hard…I asked God to forgive me for what I was doing…” (Angela, age 26, domestic servant, Ecuador)

All the women saw the provider to confirm the abortion was complete, generally within two weeks; two sought care before the scheduled visit for heavy bleeding. The 12 who had a surgical procedure had manual or electric aspiration. Eight of the 12 said they knew the drugs had not worked because they did not experience much bleeding or pain or continued to have pregnancy symptoms. Nine of them found the aspiration manageable; three found it difficult. Women said they were fearful about the surgical procedure and complained it was painful. Despite having been informed that the medication might not work, most of them were not emotionally prepared for it to fail, with one exception:

“I prepared myself psychologically and my boyfriend also prepared me psychologically. Every day, he'd call me and say, ‘We have to be prepared in case it doesn't work… you have to expect [the possibility of] the surgical abortion.’” (Silvia, age 20, university student, Colombia)

Twenty-nine women had begun using contraceptives after the abortion, 20 had not. Hormonal methods were the most frequently chosen, followed by IUDs and condoms, and one said her partner had a vasectomy. Thirteen who were not using a method said they did not have a partner; the others were told (erroneously) by their providers that they had to wait for their menstrual cycle to be regular before starting contraception.

Overall assessment after medical abortion

Almost half the women (20) described medical abortion as a form of menstrual regulation or something akin to getting one's period. Positioning the procedure in this way helped some of them to cope with their decision.

“What I did was regulate my period. I'm not going to accept that I've had an abortion because if I had been three or four months along, then I would have felt bad… But I don't feel that way because I was barely a month pregnant. What I did was simply regulate my period, nothing more.” (Marisol, age 18, domestic servant and student, Peru)

Other women described the process in more medical terms, saying that the medication caused a miscarriage. Some said the drugs dissolved the pregnancy and caused it to come out. One young woman described the pills as a time bomb because after inserting them, it was uncertain when the expulsion would take place. Some women added that, unlike surgical abortion, with medical abortion women themselves had control of the process, and its success or failure depended to a certain extent on how well they follow instructions for use of the method.

When asked to evaluate the experience, most women described both advantages and disadvantages of the method. In general, the women from Colombia, Ecuador and Peru said the main advantage of medical abortion was that it was less painful, although few of them said they had had a surgical abortion to compare with. This was also the reason they gave for choosing the method initially, and their assumption that the pain associated with medical abortion would be tolerable seemed to be affirmed by their experience. Women from urban Mexico said the main advantage was that it was practical and easy and fit well into their lives. The women from rural Mexico remarked how good it was that medication existed to help women in such situations. A recurrent theme was that medical abortion had caused little disruption to their daily lives.

“The advantage is that you can go on normally with your life… While I was going through this, I went to work just like always. I just had to be careful about the bleeding, just like when you have a heavy period… Normal, it's totally normal, you just go on with your life as you normally would.” (Ruth, age 27, government office administrator, Colombia)

The time associated with the procedure was described as both an advantage and a disadvantage of medical abortion. Some women complained about the delay before knowing if the abortion was successful or not, while others saw a benefit in how long it took.

“It gives you time to get ready for what's going to happen…In comparison, with the surgical, where you go and in a minute you know [it's over]. But with the medical… it gives you time to prepare yourself.” (Angela, age 26, domestic servant, Ecuador)

The main disadvantages described by those who found them problematic were pain and bleeding and the possibility of retained products or a failed procedure. The rural Mexican women cited provider difficulty in obtaining the pills as a disadvantage, while some Peruvian participants mentioned concern that others might find out about the abortion if it took place at home.

Of the 34 women with a complete medical abortion, 30 said they would recommend the method to a friend, whereas of the 11 who required surgical follow-up, who tended to express more negative views of medical abortion, only six said they would recommend it.

“I would tell a friend that it's an option that's not aggressive, that's tolerable, even though there are very critical moments, especially the part when the pain starts and suddenly it becomes very intense, but I would think of it as a cramp.” (Valeria, age 23, university student, urban Mexico, successful procedure)

Of those who said they would not recommend it, the majority said they did not want to encourage a woman to have an abortion. Only two specifically said they would recommend surgical over medical abortion.

“If I'd had the money, I would have had an aspiration… not only because it's quick and it's over in an instant, but because something might happen to you at home [with the medical abortion]… If you look at it, it's three nights full of anguish, worry, pain… no, I think it's terrible.” (Eliana, age 18, high school student, Peru, unsuccessful procedure)

When asked if they had felt prepared for the medical abortion experience, women from Colombia and Mexico more commonly said yes than the others. Those from Ecuador and Peru were frequently young, nulliparous and poor, and few had supportive partners. Several went through the process alone or at home among family members who were unaware of the abortion. These women also expressed feelings of guilt and concern about being judged by others. Participants from both of these countries often were being cheated on by their partners or were victims of domestic and sexual violence,Citation16Citation22 and these factors are likely to have contributed to their feeling about the abortion.

Analysing the discourses of each woman individually, we found that women who thought abortion was a sin had a more difficult experience, while those who understood the processes taking place in their bodies during the abortion had a better experience. The role of the clinician and the importance of the support they received was also key, as was the degree to which the woman was supported by her partner. In general, those who had an unsupportive or absent partner had a more difficult experience. In several cases, a supportive partner was drawn into the medical abortion process in a way that was not possible with a surgical abortion, and those women said their partners' support helped to solidify the relationship.

Discussion

All of the women interviewed underwent medical abortion under clinical supervision, and it may be that women's experiences with misoprostol obtained from a pharmacy or other source may be quite different. Several reports from Latin AmericaCitation14Citation15Citation23 found that women had not received the counselling and support, both emotional and clinical, that we found here. One of these studies found that pharmacy staff who were dispensing misoprostol gave poor quality information,Citation15 and in another providers reported that women frequently used incorrect doses of misoprostol, that were then ineffective.Citation23 However, clinicians usually come into contact with women only when they present with a problem, and little is known about the experience of women who obtain misoprostol from a pharmacy and have a complete abortion.

We conclude from our findings that medical abortion is acceptable to a wide range of women in legally restricted settings and where feasible should be made available to them. Given the influence of cost on the choice of abortion method, and the fact that medical abortion may not be appropriate for all women, cost should not be the primary reason for choosing medical abortion over a surgical method. The fact that nulliparous women tend to experience more pain with medical abortion,Citation21 should be included in counselling prior to a woman choosing the abortion method. Moreover, provision of analgesics to women using medical abortion should be routine. Lastly, the psychosocial support women receive during abortion is critical, especially for those who are more vulnerable because they see abortion as a sin, who are young or poor, who have limited knowledge about their bodies, whose partners are not supportive or who became pregnant through sexual violence.

After years of stagnation on this issue in the region, debate about abortion in Latin America has grown increasingly more public and appears to be effecting important changes that will enable more women to have access to safe abortion services. Efforts in Mexico to expand the legal indications for abortion in different states and increase access to legal abortion services have increased during the past six years and have been particularly successful in the Federal District of Mexico City.Citation24Citation25 In Colombia in 2005, a lawyer has challenged the country's restrictive abortion law using international human rights arguments,Citation26 and in 2004, Guyana registered mifepristone for use as an abortifacient. Now that the World Health Organization has added mifepristone and misoprostol to the list of essential medicines,Citation27 it seems clear that regardless of legality, more women throughout the region will surely be using medical abortion in the future.

Acknowledgements

Our thanks to Gloria Maira, Olivia Ortiz, Imelda Martínez and Margoth Mora for their help with data collection, Katrina Abuabara for assistance with the initial coordination of the study and Batya Elul for sharing study instruments. Claudia Díaz translated the first draft of this manuscript from Spanish to English. A portion of this work was presented at the International Consortium for Medical Abortion meeting in Johannesburg, 17-20 October 2004, at the American Public Health Association Annual Meeting, Washington, DC, 7-10 November 2004, and at the XXV International Population Conference of the International Union for the Scientific Study of Population, Tours, 18-23 July 2005. The project was funded by Gynuity Health Projects and an anonymous donor.

Notes

* Three drug regimens for medical abortion have been used internationally: mifepristone plus misoprostol, misoprostol alone and methotrexate plus misoprostol.Citation6 In Latin America, mifepristone is registered and marketed in very few countries.

References

- Alan Guttmacher Institute. Aborto Clandestino: Una Realidad Latinoamericana. 1994; AGI: New York.

- World Health Organization. Unsafe abortion: global and regional estimates of the incidence of unsafe abortion and associated mortality in 2000. 4th ed, 2004; WHO: Geneva.

- Abortion laws of the world. At: . <http://annualreview.law.harvard.edu/population/abortion/abortionlaws.htm>. Accessed 28 May 2005.

- Global Health Council. Promises to keep. At: <http://www.globalhealth.org/assets/publications/PromisesToKeep.pdf. >. Accessed 28 May 2005.

- DL Billings, J Benson. Postabortion care in Latin America: policy and service recommendations from a decade of operations research. Health Policy and Planning. 20(3): 2005; 158–166.

- R Kulier, AM Gülmezoglu, GJ Hofmeyr. Medical methods for first trimester abortion (Cochrane Review). The Cochrane Library, Issue 1. 2004; Oxford: Update Software.

- A Faúndes, LC Santos, M Carvalho. Post-abortion complications after interruption of pregnancy with misoprostol. Advances in Contraception. 12(1): 1996; 1–9.

- SH Costa. Commercial availability of misoprostol and induced abortion in Brazil. International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics. 63(Suppl.1): 1998; S131–S139.

- D Ferrando. Clandestine Abortion in Peru: Facts and Figures. 2002; Centro de la Mujer Peruana, Pathfinder International: Lima.

- RM Barbosa, M Arilha. The Brazilian experience with Cytotec. Studies in Family Planning. 24(4): 1993; 236–240.

- D Walker, L Campero, H Espinoza. Deaths from complications of unsafe abortion: misclassified second trimester deaths. Reproductive Health Matters. 12(24 Suppl): 2004; 27–38.

- D Billings. Misoprostol alone for early medical abortion in a Latin American clinic setting. Reproductive Health Matters. 12(24 Suppl): 2004; 57–64.

- H Espinoza, K Abuabara, C Ellertson. Physicians' knowledge and opinions about medication abortion in four Latin American and Caribbean region countries. Contraception. 70(2): 2004; 127–133.

- J Sherris, A Bingham, MA Burns. Misoprostol use in developing countries: results from a multicountry study. International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics. 88(1): 2005; 76–81.

- D Lara, K Abuabara, D Grossman. Pharmacist provision of medical abortifacients in Mexico City. At: <http://apha.confex.com/apha/132am/techprogram/paper_87582.htm. >. Accessed 28 May 2005.

- I Goicolea. Exploring women's needs in an Amazon region of Ecuador. Reproductive Health Matters. 9(17): 2001; 193–202.

- M Mora, J Villareal. Unwanted pregnancy and abortion: Bogotá, Colombia. Reproductive Health Matters. 2: 1993; 11–20.

- A Amuchástegui Herrera, M Rivas Zivy. Clandestine abortion in Mexico: a question of mental as well as physical health. Reproductive Health Matters. 10(19): 2002; 95–102.

- E Ellertson, B Elul, B Winikoff. Can women use medical abortion without medical supervision?. Reproductive Health Matters. 9: 1997; 149–161.

- C Harper, C Ellertson, B Winikoff. Could American women use mifepristone-misoprostol pills safely with less medical supervision?. Contraception. 65: 2002; 133–142.

- H Hamoda, PW Ashok, GM Flett. Analgesia requirements and predictors of analgesia use for women undergoing medical abortion up to 22 weeks of gestation. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 111(9): 2004; 996–1000.

- AB Coe. From anti-natalist to ultra-conservative: restricting reproductive choice in Peru. Reproductive Health Matters. 12(24): 2004; 56–69.

- C Rodríguez Lara. Home use: Mexican women's experience. At: <http://www.medicalabortionconsortium.org/ICMA_PPT_FILES/ICMACONF/TUESDAY1/RODRIGUE/frame.htm. >. Accessed 28 May 2005.

- M Lamas, S Bissell. Abortion and politics in Mexico: ‘context is all’. Reproductive Health Matters. 8(16): 2000; 10–23.

- DL Billings, C Moreno, C Ramos. Constructing access to legal abortion services in Mexico City. Reproductive Health Matters. 10(19): 2002; 86–94.

- Landmark constitutional challenge in Colombia seeks to loosen one of world's most restrictive abortion laws. At: . <http://www.womenslinkworldwide.org/pdf/co_lat_col_pressrelease.pdf>. Accessed 10 August 2005.

- WHO Essential Medicines Library. At: . <http://mednet3.who.int/EMLib/DiseaseTreatments/MedicineDetails.aspx?MedIDName=443@mifepristone-misoprostol>. Accessed 10 August 2005.