Abstract

A long-held belief among mental health practitioners is that being born unwanted carries a risk of negative psychosocial development and poor mental health in adulthood. The Prague Study was designed to test this hypothesis. It followed the development and mental well-being of 220 children (now adults) born in 1961–63 in Prague to women twice denied abortion for the same unwanted pregnancy. The children were individually pair-matched at about age nine with 220 children born from accepted pregnancies when no abortion had been requested. This article brings together in one place the theoretical assumptions and hypotheses, the criteria for selecting the study participants and major findings from five follow-up waves conducted among the children around the ages of 9, 14–16, 21–23, 28–31 and 32–35 years, plus a sub-study of married unwanted pregnancy subjects and accepted pregnancy controls at ages 26–28. To control for potential confounding factors in data interpretation, all siblings of all subjects were included in the last two waves. It was found that differences in psychosocial development widened over time but lessened at around age 30. All the differences consistently disfavoured the unwanted pregnancy subjects, especially only children (no siblings). They became psychiatric patients (especially in-patients) more frequently than the accepted pregnancy controls and also more often than their siblings. The overall findings suggest that, in the aggregate, denial of abortion for unwanted pregnancy entails an increased risk for negative psychosocial development and mental well-being in adulthood. © 2006 Reproductive Health Matters.

Résumé

Les praticiens de santé mentale croient depuis longtemps que les enfants non désirés courent un risque de développement psychosocial négatif et de mauvaise santé mentale à l'âge adulte. L'étude de Prague souhaitait tester cette hypothèse. Elle a suivi le développement et le bien-être mental de 220 enfants (aujourd'hui adultes) nés en 1961-63 à Prague d'une mère à laquelle on avait refusé par deux fois l'avortement qu'elle sollicitait. À l'âge de 9 ans environ, ces enfants ont été associés individuellement à 220 enfants nés d'une grossesse pour laquelle un avortement n'avait pas été demandé. Cet article réunit les postulats et les hypothèses, les critères de sélection des participants à l'étude et les principales conclusions de cinq cycles de suivi réalisés chez les sujets âgés de 9 ans, 14-16 ans, 21-23 ans, 28-31 ans et 32-35 ans, ainsi que d'une sous-étude des sujets de grossesses non désirées et des membres du groupe de contrôle mariés à 26-28 ans. Pour réduire les facteurs susceptibles de fausser l'interprétation, la fratrie des sujets a été incluse dans les deux derniers cycles. L'étude a révélé que les différences dans le développement psychosocial s'accentuaient avec le temps, mais diminuaient vers l'âge de 30 ans. Les sujets non désirés, en particulier les enfants uniques, avaient un développement moins favorable. Ils ont dû recevoir des soins psychiatriques (et être internés) plus fréquemment que les membres du groupe de contrôle et que leur fratrie. Les conclusions globales indiquent que le refus de l'avortement pour une grossesse non désirée entraîne un risque accru pour le développement psychosocial et le bien-être mental à l'âge adulte.

Resumen

Hace mucho que los profesionales de la salud mental sostienen que el nacer sin ser deseado acarrea un riesgo de desarrollo psicosocial negativo y salud mental deficiente en la adultez. Diseñado para probar esta hipótesis, el estudio de Praga siguió el desarrollo y bienestar mental de 220 niños nacidos en 1961–63, en Praga, de mujeres a quienes se les negó dos veces el aborto del mismo embarazo no deseado. A la edad de nueve años (aprox.), los niños fueron emparejados con 220 niños nacidos de embarazos aceptados en los que no se solicitó un aborto. En este artículo se exponen las suposiciones teóricas y las hipótesis, los criterios de selección de los participantes del estudio y los principales resultados de cinco oleadas de seguimiento, realizadas entre niños en las edades de 9, 14–16, 21–23, 28–31 y 32–35, así como un subestudio de participantes casados producto de embarazos no deseados y de participantes de control, producto de embarazos aceptados, de 26 a 28 años. Para realizar un control de factores posiblemente confusos en la interpretación de los datos, se incluyeron en las últimas dos oleadas todos los hermanos y hermanas de todos los participantes. Se encontró que las diferencias en el desarrollo psicosocial aumentaron con el tiempo pero disminuyeron cerca de los 30 años. Todas las diferencias perjudicaron a los participantes que eran producto de embarazos no deseados, especialmente los hijos únicos. Pasaron a ser pacientes psiquiátricos (en particular pacientes internos) con más frecuencia que los controles producto de embarazos aceptados y también con más frecuencia que sus hermanos o hermanas. Los resultados generales sugieren que la denegación del aborto en casos de embarazo no deseado implica mayor riesgo de desarrollo psicosocial y bienestar mental negativos en la adultez.

There has been much discussion of the dynamics of intended and unintended conceptions, and wanted and unwanted pregnancies, and of subsequent voluntary or involuntary childrearing. However, it has seldom been possible to conduct follow-up studies from childhood to adulthood of children unwanted at conception or during early pregnancy. Conducting research on the developmental and mental health effects of denied abortion requires a legal system that approves certain requests for pregnancy termination and rejects others. Also needed is a national population register that records medical events and facilitates follow-up of children delivered involuntarily. Czechoslovakia (now the Czech Republic) was one of the few countries meeting these conditions at the time the Prague Study (as it became known internationally) was initiated in 1969.

The Prague Study began when an abstract of a Czech paper on social questions of pregnancy interruption by Drs. Vratislav Schüller and Eva Stupkova came to my attention.Citation1 On meeting Dr. Stupkova, then Director of the Prague Public Health Services, I learned that during the years 1961–63 she had been Chair of the Prague Regional Appellate Abortion Commission. She had kept in her possession the names of the women twice denied abortion for the same pregnancy, once on original request and again on appeal. Dr. Stupkova was willing to make her material available for a follow-up study. In consultation with Drs. Zdenek Dytrych, Zdenek Matejcek and Vratislav Schüller, I developed the original pair-matched research design that was supported over the years by US, Czech and international donor organisations. All the research was conducted under the auspices of the Prague Psychiatric Research Institute (now the Prague Psychiatric Centre). I secured grants, served as senior consultant to all phases of the Prague Study, and wrote and/or edited English language reports.Citation2Citation3 I also arranged a presentation by Stupkova and SchüllerCitation4 at an international seminar and publication of an English language article.Citation5 Dr. Ludek Kubicka developed the concept of the sibling studies, conducted all the data analyses in consultation with Ing. Zdenek Roth, and was the senior author of related research reports.Citation6Citation7 Matejcek and Dytrych, both now deceased, supervised the field studies coordinated by Ms. Karla Topicova and were co-authors of early international publications and presentations.Citation8Citation9 Schüller, also deceased, managed the pair-matching process and for years was the only person to know “who was who”,.

The few related studies in the literature, mostly from Sweden and Finland, were reviewed in previous publications.Citation2Citation3Citation6Citation7 The Swedish studies Citation10Citation11Citation12Citation13Citation14Citation15Citation16 indicated that children born to women denied abortion for an unwanted pregnancy tended to be less well adjusted socially, were more often in psychiatric care and were more frequently registered for crimes than children born from accepted pregnancies. The results of the Finnish studyCitation17Citation18Citation19 showed that unwantedness was frequently associated with less favourable socio-economic circumstances.

This article brings together in one place major findings from five follow-up waves conducted around ages 9, 14–16, 21–23, 28–31, and 32–35 years and a substudy of married subjects and controls (the latter from accepted pregnancies) at ages 26–28. Descriptions of data collection methods (individually administered questionnaires, structured interviews and public registers) as well as detailed statistical analyses of the empirical findings with tables and graphs have been presented over the years in nearly 100 papers and books, published, thus far, in five languages.

The setting

Following decriminalisation of abortion in the Soviet Union, the Government of Czechoslovakia liberalised its abortion law in December 1957, providing termination of pregnancy on medical and “other” grounds during the first three months of gestation.Citation2 Approval of a woman's request for pregnancy termination was the responsibility of the District Abortion Commission. If that Commission denied the request, the woman had the right to appeal to a Regional Appellate Abortion Commission, whose decision was final. Requests were denied mostly because the woman had presented false or insufficient reasons for abortion, or because she was more than 12 weeks pregnant, or because another pregnancy had been terminated during the immediately preceding months. Appealing a denial and making a second request to terminate the same pregnancy constituted empirical confirmation that the pregnancy was strongly unwanted, at least in its early stages.

Hypotheses

The theoretical assumption underlying the study evolved from the concept of psychological deprivation.Citation20 It was believed that if there is a continuum of depriving conditions (ranging from a child's isolation in an institutional setting to relatively mild emotional neglect in a dysfunctional family), there is also likely to be a continuum of consequences (from severe to relatively mild). This assumption underlies the concept of psychological sub-deprivation. Citation21Citation22 The basic hypothesis to be tested was that differences between children born from unwanted pregnancies and children born from accepted pregnancies would be to the disadvantage of the unwanted pregnancy children. Disparities were expected to be apparent in their medical history, social integration, educational achievement, psychological condition and family relations. This expectation, together with the impression that boys are more vulnerable than girls to adverse social–environmental conditions, led to the prediction that unwanted pregnancy boys would suffer relatively more than girls.Citation23 It was also understood from the beginning that although the unwanted pregnancy subjects were selected on the basis of unwantedness during early pregnancy, many of these children were likely to become accepted, or indeed loved, after they were born.

To safeguard confidentiality, the research project was officially described as the Prague Study of Child Development. The topic of abortion was raised only once – as the final question in the first interview with the mother who had been twice denied abortion for the same pregnancy. At the time of the interview nine years later, 83 (38%) of the 220 mothers denied ever having requested an abortion for that pregnancy. The issue of unwantedness was never raised in any of the structured individual interviews with the study participants and never brought up by anyone.

The sample

Fortuitous circumstances made it possible to gain access to the 1961–63 records of the Prague Appellate Abortion Commission. Of the 24,889 applications for abortion, 638 (2%) were rejected on initial request and again on subsequent appeal.Citation2 After excluding 83 women who were not Prague residents or were citizens of another country, 555 women remained whose request for termination of an unwanted pregnancy had been twice denied. Of these, 31 women had moved out of Prague; nine had given false addresses on their abortion applications; six were found not to have been pregnant; and eight were untraceable for other reasons. Of the 501 women for whom information was available, 316 (63%) had carried their pregnancies to term while residing in Prague. Of the remaining 185 women (37%), 43 had obtained legal abortions after requesting termination from another district abortion commission; 80 were alleged to have aborted spontaneously (a percentage twice that normally expected); and 62 had no record of having given birth. The finding that 37% of the women twice denied abortion managed not to give birth suggests that the most extreme cases of unwantedness were excluded from the study before it began.

The 316 traceable Prague women gave birth to 317 live children. Of these, six died (five during the first year) and 19 were adopted, a proportion exceeding the national average by more than 30 times. An additional 39 children had moved with their parents from Prague and two were placed in institutional care. Four mothers denied ever having had a child, although hospital records showed that they had delivered one. Three women had died, and the children of three others were living with relatives in rural areas. Only seven mothers refused to co-operate with the research project. The remaining 233 women and their children were located in Prague when the research study was initiated. However, 13 of the children could not be successfully pair-matched, thus reducing the sample to 220 children, 110 boys and 110 girls.

The controls

Each unwanted pregnancy child was demographically pair-matched at age nine with an accepted pregnancy control child whose mother's name was not found on the abortion request registers. Pair matching of children was for age, sex, birth order, number of siblings and school. Mothers were matched for age, socio-economic status (as determined by their and their partners' educational level), and by the partner's presence in the home (that is, completeness of the family). All the children were reared in two-parent homes, although sometimes with a father substitute in lieu of the biological father. To include as many of the unwanted pregnancy children as possible, it was necessary to match some of the three-child families (where one or two additional children were born after the unwanted pregnancy) with two-child accepted pregnancy families. There were 50 only children (no siblings) in both samples. The matching process was accomplished by one colleague who remained the only member of the research team to know which child belonged to what sample.

Siblings

All three initial follow-up studies (at ages 9–23) showed that the unwanted pregnancy families were less stable and more dysfunctional than the accepted pregnancy families. To control for previously unmeasured confounding effects in data interpretation, it was decided to invite all siblings of both sample subjects to participate in the next two follow-up waves. The purpose was to put to a stronger test the hypothesis that an unwanted pregnancy has negative effects on psychosocial development and mental health. Using the terminology of behavioural genetics,Citation26 a distinction was made between shared (by siblings) and non-shared (for a particular child) family environment. It was hypothesised that the effect of unwantedness is non-shared (by siblings).

A literature search yielded only one other study using siblings.Citation24 Data from 3,000 American families when the subjects were between 4 and 13 years of age, showed that unwanted pregnancy did not have significant effects on infant health or early child development. This was similar to the findings of a review of local health clinic records and other observations when the Prague subjects were of a similar age.Citation25

First follow-up wave: age nine

Review of early childhood health records showed that both groups of children had started life under similar conditions.Citation2 There were no statistically significant differences in birth weight or length, in the incidence of congenital malformation, or in signs of minimal brain dysfunction (now defined as attention-deficit hypertensive activity disorder). However, the unwanted pregnancy children were breast-fed for a significantly shorter time or not at all. They also tended to be slightly but consistently overweight. At age nine, both groups obtained similar mean scores on the Czech version of the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children – 102 for the unwanted pregnancy children and 103 for the controls. However, the unwanted pregnancy children received lower school grades in the Czech language and were rated less favourably on school performance, diligence and behaviour by their teachers and mothers. On sociometric scales, the unwanted pregnancy children were significantly more often “rejected as a friend” by their schoolmates than were the controls. Compared to the mothers who accepted their pregnancy, the unwanted pregnancy mothers perceived their sons less favourably than their daughters. They also more often entrusted childrearing to someone else. A history of three or more abortions was four times more frequent among unwanted pregnancy mothers than among the control mothers.

To develop an aggregate indicator of maladaptation, 60 factual items were selected from the case history material, questionnaires and other psychological assessment instruments, which together yielded a Maladaptation Score, reflecting negative qualities, lack of maturity or demonstrated proneness to problems in the socialisation process. The child's score was formed by summing up his/her “negative points”. The group identity of individuals remained unknown when the data were scored and tabulated.

The unwanted pregnancy children had significantly higher maladaptation scores than the controls. The boys' mean scores were considerably higher than the girls. The highest scores were obtained by the 50 unwanted pregnancy only children, while the 50 accepted pregnancy only children had the lowest. Among the unwanted pregnancy boys, the only children had the highest maladaptation scores. Otherwise healthy and intelligent children seemed, in the aggregate, to become less adaptive, less socially mature and less prepared to cope with the demands of social life. The mothers' maladaptation scores were created similarly, based on negative indicators selected from the case histories, structured interviews, questionnaires and medical records. The unwanted pregnancy mothers' maladaptation scores were significantly higher than the control mothers' scores.

Follow-up wave two: ages 14–16

The second follow-up wave was conducted in 1977 when the children were 14–16 years old.Citation27 A 98% follow-up rate was attained. Previously non-significant differences in school performance reached statistical significance. This difference was not so much of unwanted pregnancy children failing more often, but rather in their being substantially under-represented among students graded above average or higher. They rarely appeared on any roster of excellence. Similar findings were noted in teachers' ratings. As compared to the controls, a significantly larger number of unwanted pregnancy children did not continue their education to secondary school. Instead, they became apprentices or started jobs without prior vocational training. In all the areas sampled, earlier differences had not only persisted but widened.

Follow-up wave three: ages 21–23

Findings from the third follow-up wave in 1983–84 reflected a significantly greater proneness to problems among unwanted pregnancy subjects than control subjects, now 21–23 years old, tending to confirm the predictions of the maladaptation scores obtained at age nine.Citation25 Of those interviewed, less than one-third as many unwanted pregnancy subjects as control subjects said their lives had developed as expected, and more than twice as many stated that they had encountered more problems than anticipated. Similarly, a significantly smaller proportion of mothers who delivered unwanted pregnancies than control mothers expressed satisfaction with their child's development, and a significantly larger proportion expressed dissatisfaction with their child's present educational and social status.

Compared to the controls, the young adults born of unwanted pregnancies reported significantly less job satisfaction, more conflict with co-workers and supervisors, fewer and less satisfying relations with friends, and more disappointments in love. More were dissatisfied with their mental well-being and actively sought or were in treatment. Twice as many unwanted pregnancy subjects as controls had been sentenced to prison terms.

A Psychosocial Instability Score was constructed on the basis of structured interview responses to 37 items considered indicative of unsatisfactory or problematic relationships. It was constructed as an aggregate measure, on a similar basis as the Maladaptation Score. The mean scores for all examined subjects showed highly significant differences (p<.001). The differences in what the subjects said about themselves at age 21–23 tended to be even greater than the differences in what parents, teachers and schoolmates had said about them more than a decade earlier. However, the previously noted gap between unwanted pregnancy boys and girls on the Maladaptation Score at age nine was no longer apparent.Citation2

Partner choices: ages 26–28

In 1989 a supplementary study was conducted to assess partner choices among married subjects.Citation28 There were significantly more single and divorced unwanted pregnancy women than control women (p<.05). Also, significantly more unwanted pregnancy men than control men were married. Compared to female partners of control men, female partners of unwanted pregnancy men had experienced significantly more abortions and more repeat abortions, and were more often dissatisfied with their jobs and mental well-being. On examining all available data, it was found that female partners of men born from unwanted pregnancies were in many ways similar to women born from unwanted pregnancies. Compared to male partners of control women, male partners of unwanted pregnancy women more often reported encountering unexpected problems and had more difficult marital relations. In many ways they were similar to men born from unwanted pregnancies.Citation28

In a substudy comparing subjects who were married and had at least one child, the unwanted pregnancy women more frequently reported that they were unprepared for their first pregnancy, “felt less happy” during pregnancy, and “felt like mothers” only after delivery.Citation28

For information on pregnancy, childbirth and child care, the unwanted pregnancy women turned more often to the media and friends, whereas control women turned more often to their mothers. They also returned to work earlier than the control mothers. Compared to the control fathers, the unwanted pregnancy fathers more often reported “not being on speaking terms” with their spouses and frequently perceived themselves as not fulfilling their parental roles.

In sum, differences noted between the families of unwanted pregnancy and accepted pregnancy subjects were uniformly to the disadvantage of families founded by unwanted pregnancy subjects.

Follow-up wave four: ages 28–31

The fourth follow-up wave was conducted in 1992–93 when the subjects were about 30 years old.Citation6 Of the original 220 unwanted pregnancy subjects, 190 (86%) agreed to participate. Two had died, nine were outside the country, three were in prison and 16 could not be contacted or refused to participate. Of the original 220 accepted pregnancy subjects, 200 (90%) participated. Five had died, four were out of the country, two were in prison and nine could not be contacted or refused to participate. Of the 173 siblings of unwanted pregnancy subjects, 162 (94%) participated. Two had died, three were out of the country and six could not be contacted or declined to participate. Of the 171 siblings of accepted pregnancy subjects, 160 (93%) participated. Five were out of the country and six could not be located or refused. None were in prison. About 73% of the siblings were older than the study subjects. Only subjects (without siblings) and siblings younger than 20 years were excluded from the data analyses. Data sources included fact-based official registers of criminal convictions, alcohol and drug abuse, unemployment and parenting problems that had come to the attention of the authorities. Indicators were constructed from subjects' responses to a socialisation scale, a mood frequency questionnaire (which measured anxiety and depression), a social development questionnaire and a social integration scale.Citation6

Although the subjects born from unwanted pregnancies still manifested less favourable psychosocial adaptation at age 30 than the pair-matched controls, the differences had narrowed. However, the differences between unwanted pregnancy women and their controls were now wider than those between unwanted pregnancy men and their controls. More unwanted pregnancy women than control women were registered as unmarried or frequently divorced, or having difficulties in parenting or being unemployed. No such differences were observed between unwanted pregnancy men and their controls or between the siblings of all the original study participants.

Results from computerised regression analyses of siblings of the original study participants supported the hypothesis that the less favourable psychosocial development of unwanted pregnancy subjects (at least partially) was due to unwantedness, not shared by their siblings.Citation6 The non-shared harmful effects of unwantedness were found primarily in females. On average, women born from unwanted pregnancies were less emotionally stable and less well socially integrated than female controls born from accepted pregnancies. No such differences were found between female siblings of women born from unwanted pregnancies or their accepted pregnancy controls. Females born from unwanted pregnancies were also on average less well socialised and more frequently in a depressed mood. They reported having been in psychiatric care (during their life) significantly more often than their siblings or controls.

Follow-up wave five: ages 32–35

In 1996–97 the original unwanted pregnancy subjects, their controls and their siblings who were still residing in Prague were invited to participate in a one hour face-to-face structured interview conducted in the respondents' homes.Citation7 The exclusion of subjects residing outside of Prague was dictated by cost considerations and was not believed to have biased the results. Of the original 220 unwanted pregnancy subjects, 164 (74.5%) participated as did 166 (75.5%) of the original accepted pregnancy controls. Of the original 173 siblings of unwanted pregnancy subjects, 119 (68.8%) cooperated as did 124 (72.5%) of the 171 siblings of the controls. Of the many items in the structured interview, only those leading to variables indicating poor mental health were used in the very extensive data analysis designed by Kubicka.Citation7 The focus was on psychiatric morbidity.

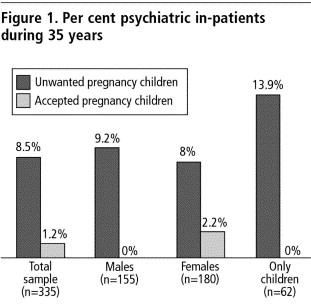

Being born from an unwanted pregnancy was significantly related to psychiatric treatment in adulthood. The unwanted pregnancy subjects became psychiatric patients more frequently than the controls and also more often than their siblings. On nine out of ten indicators of poor mental health, ranging from psychiatric inpatient treatment to unsatisfactory sexual relations, the percentage of disturbed unwanted pregnancy subjects was higher than the percentage among their siblings. The differences between the accepted pregnancy controls and their siblings were mostly small, with a slightly higher percentage found among the siblings on most measures. Unwanted pregnancy significantly predicted three of the ten poor mental health indicators, in particular psychiatric inpatient and outpatient treatment and a combination of symptoms reflecting a probable anxiety or depressive disorder.

Figure 1 shows the extent of psychiatric inpatient experience (over the 35 years) of unwanted pregnancy subjects and accepted pregnancy controls for the total sample – males, females and only children (no siblings). Particularly noteworthy is that the unwanted pregnancy only children had the highest percentage (13.9%) of psychiatric treatment compared to nil for the accepted pregnancy only children controls. Additional analyses comparing unwanted pregnancy subjects to their younger or older siblings showed that adults born of unwanted pregnancies became psychiatric inpatients more often only in comparison to their older siblings.Citation7

The use of siblings as controls demonstrated that not only the unwanted pregnancy subjects but also their siblings included higher percentages of poorly socialised individuals than did the accepted pregnancy control subjects and their siblings. Both genetic and environmental factors may explain the finding that in families with a child born from an unwanted pregnancy a larger percentage of all the children tended to be less socialised than the children of women who accepted their pregnancies. Alcohol or drug abuse, heavy smoking and criminality were not found to be related to unwanted pregnancy.Citation6Citation7 In sum, even when accepting only the analyses with sibling controls as methodologically adequate, the findings from follow-up waves four and five lend at least partial support to the hypothesis that being born from an unwanted pregnancy has longer-term negative effects.

Discussion

The first three follow-up waves of the Prague Study showed that differences between unwanted pregnancy subjects and accepted pregnancy controls matched on socio-demographic variables widened over time and then declined around age 30, similar to the findings from Sweden.Citation2Citation12 However, all the differences in psychosocial development were consistently in disfavour of the subjects born from unwanted pregnancies, especially among those who were only children. These subjects were not so much over-represented on extremely negative indicators as they were under-represented on any indicator of excellence (such as academic achievement, job satisfaction or parenting).

As noted by Kubicka,Citation6Citation7 when study participants are matched for socio-demographic variables only, some possible confounding factors remain uncontrolled. Results from waves four and five, when siblings were included, showed that being born from an unwanted pregnancy was significantly related to psychiatric treatment any time in life. The unwanted pregnancy subjects became psychiatric patients (especially inpatients) more often than the controls born from accepted pregnancies and also more often than their older siblings. The greatest differences were found between unwanted pregnancy only children (no siblings) and their controls. This finding lends credence to the observation that some women reject the role of mother. Moreover, it was the impression of the social workers who did the interviews (around age nine) that the mothers of children born from unwanted pregnancies were emotionally cold towards those children. However, some unwanted pregnancy children developed as well as their accepted pregnancy controls, showing resiliency in the circumstances.Citation29

Siblings are less than ideal controls. The occurrence of an unwanted pregnancy followed by an involuntary birth very likely had a negative influence on the mental health of the mother and the family environment. This situation probably also affected the sibling(s) of the unwanted pregnancy child. Nevertheless, at least partial support for the hypothesis was obtained. A sub-study of married subjects with children suggested that differences between subjects born from unwanted and accepted pregnancies may persist into the next generation. This topic is worthy of further research.

To the best of our knowledge, the Prague Study is the only one of children born to women twice denied abortion for the same unwanted pregnancy and socio-demographically pair-matched controls born of accepted pregnancies to other parents, as well as siblings of both groups of subjects. The Finnish and Swedish studies did not include pair-matched control subjects or siblings.Citation10Citation11Citation12Citation13Citation14Citation15Citation16Citation17Citation18Citation19 Since the Prague Study is so unique, it can be argued that further research is needed to support the findings. However, the findings may also underestimate the effects of unwantedness when it is considered that those Czech women who were truly determined not to give birth managed not to do so.

Although different contexts might lead to different findings in other countries, the Prague Study lends support to the hypothesis that psychological sub-deprivationCitation21Citation22 constitutes a serious social and public health problem. It seems that the increased risk for detrimental psychosocial development evolves from a combination of circumstances that begins with an unwanted pregnancy and denial of abortion. Unwantedness in early pregnancy foreshadows a family atmosphere unlikely to be conducive to healthy childrearing.

In the aggregate, being born from an unwanted pregnancy entails an increased risk for negative psychosocial development and mental well-being (at least up to age 35, the end of the study). Implications for public health policy and abortion legislation are apparent in the decision of the Government of Czechoslovakia (partially in response to results from the Prague Study), to abolish abortion commissions in 1986. Termination of an unwanted pregnancy became available on written request of the woman provided her pregnancy did not exceed 12 weeks and there were no contraindications.

Acknowledgments

This article builds on a presentation given at the IUSSP International Population Conference, Tours, France, 18–23 July 2005, and summarises previous publications noted in the text and references. The Prague Study was funded at various times by the US National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (Grants HD 05569 and HD 25574), Ford Foundation, World Health Organization (Geneva and Copenhagen offices), United Nations Fund for Population Activities, World Federation for Mental Health Committee on Responsible Parenthood, Czechoslovak State Research Plan, Ministry of Health of the Czech Republic (Grants 289-4 and NF/5536-03), and the Research Support Scheme of the Open Society Foundation (Grant 85/1999). It is with deep gratitude and appreciation that I acknowledge the support of two directors of the Prague Psychiatric Center, Drs. L Hanzlicek and C Höschl. They safeguarded the Prague Study over the years. Ours was one of the few Czech–US cooperative projects that survived the Soviet occupation in 1968. I also wish to acknowledge the many helpful suggestions made by Drs. Warren B Miller and the late Herbert Friedman, both affiliated with the Transnational Family Research Institute.

References

- V Schüller, E Stupkova. [Social questions of pregnancy interruption and possibilities of their study (in Czech)]. Demografie. 9: 1967; 216–220.

- David HP, Dytrych Z, Matejcek Z, et al (editors). Born Unwanted: Developmental Effects of Denied Abortion. New York: Springer, 1988; Prague: Avicenum, 1988: Mexico City: EDAMEX, 1991.

- HP David, Z Dytrych, Z Matejcek. Born unwanted: observations from the Prague Study. American Psychologist. 58: 2003; 224–229.

- V Schüller, E Stupkova. Legal abortion and the possibilities of studying its psychosocial consequences. HP David. Transnational Studies in Family Planning. 1969; American Institutes for Research: Budapest and Washington, 12–14.

- V Schüller, E Stupkova. The “unwanted child” in the family. International Mental Health Research Newsletter. 14: 1972; 6–11. 14–18.

- L Kubicka, Z Matejcek, HP David. Children from unwanted pregnancies in Prague, Czech Republic, revisited at age thirty. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 91: 1995; 361–369.

- Kubicka L, Roth Z, Dytrych Z, et al. The mental health of adults born from unwanted pregnancies, their siblings, and matched controls: a 35-year follow-up study from Prague, Czech Republic. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 2002;190:653–62 and 2003;191:137.

- Z Dytrych, Z Matejcek, V Schüller. Children born to women denied abortion. Family Planning Perspectives. 7: 1975; 165–171.

- Z Matejcek, Z Dytrych, V Schüller. Children from unwanted pregnancies. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 57: 1978; 67–90.

- H Forssman, I Thuwe. One hundred and twenty children born after application for therapeutic abortion refused. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 42: 1966; 71–88.

- H Forssman, I Thuwe. Continued follow-up of 120 persons after refusal for therapeutic abortion. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 64: 1981; 142–146.

- H Forssman, I Thuwe. The Gőteborg cohort. HP David, Z Dytrych, Z Matejcek. Born Unwanted: Developmental Effects of Denied Abortion. 1988; Springer: New York, 37–45.

- K Höök. Refused abortion:a follow-up study of 249 women whose applications were refused by the National Board of Health in Sweden. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 39(Supplement): 1963; 168.

- K Höök. The unwanted child: effects on mothers and children of refused applications for abortion. In Society, Stress and Disease. 1975; Oxford Medical Publications: Oxford, 187–192.

- S Bloomberg. Influence of maternal distress during pregnancy on postnatal development. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 62: 1980; 405–417.

- HP David. Additional studies from Sweden. HP David. Born Unwanted: Developmental Effects of Denied Abortion. 1988; Springer: New York, 46–52.

- A Myhrman. The northern Finland cohort. HP David. Born Unwanted: Developmental Effects of Denied Abortion. 1988; Springer: New York, 103–110.

- A Myhrman, P Olsen, P Rantakallio. Does the wantedness of a pregnancy predict a child's educational achievement?. Family Planning Perspectives. 27: 1995; 116–119.

- A Myhrman, P Rantakallio, M Sohanni. Unwantedness of a pregnancy and schizophrenia in the child. British Journal of Psychiatry. 169: 1996; 637–640.

- J Langmeier, Z Matejcek. Psychological deprivation in childhood. 1975; Wiley: New York.

- Z Matejcek. [Concept of psychological sub-deprivation (in Czech)]. Psychologia a Patopsychologia Dietata. 22: 1987; 419–428.

- Z Matejcek, Z Dytrych. Specific learning disabilities and the concept of psychological sub-deprivation: the Czechoslovak experience. Learning Disabilities Research and Practice. 8: 1993; 44–51.

- J Bowlby. Attachment and Loss. 1969; Hogarth: London.

- TJ Joyce, R Kaestner, S Korenman. The effect of pregnancy intention on child development. Demography. 37: 2000; 83–94.

- Z Matejcek, Z Dytrych, V Schüller. The Prague cohort through age nine. HP David. Born Unwanted: Developmental Effects of Denied Abortion. 1988; Springer: New York, 53–86.

- R Plomin, D Daniels. Why are children in the same family so different from one another?. Behavioral and Brain Sciences. 10: 1997; 1–16.

- Z Dytrych, Z Matejcek, V Schüller. The Prague cohort: adolescence and early adulthood. HP David. Born Unwanted: Developmental Effects of Denied Abortion. 1988; Springer: New York, 87–102.

- HP David, Z Dytrych, Z Matejcek. Partner choice among young adults born from unwanted and accepted pregnancies in Czechoslovakia. M Kessler. The Present and Future of Prevention. 1992; Sage: Newbury Park, 169–181.

- Z Matejcek, HP David, Z Dytrych. Questions and answers: discussion and suggestions. HP David. Born Unwanted: Developmental Effects of Denied Abortion. 1988; Springer: New York, 111–127.