Abstract

Structural and social inequalities, a harsh political economy and neglect on the part of the state have made married adolescent girls an extremely vulnerable group in the urban slum environment in Bangladesh. The importance placed on newly married girls' fertility results in high fertility rates and low rates of contraceptive use. Ethnographic fieldwork among married adolescent girls, aged 15–19, was carried out in a Dhaka slum from December 2001–January 2003, including 50 in-depth interviews and eight case studies from among 153 married adolescent girls, and observations and discussions with family and community members. Cultural and social expectations meant that 128 of the girls had borne children before they were emotionally or physically ready. Twenty-seven had terminated their pregnancies, of whom 11 reported they were forced to do so by family members. Poverty, economic conditions, marital insecurity, politics in the household, absence of dowry and rivalry among family, co-wives and in-laws made these young women acquiesce to decisions made by others in order to survive. Young married women's status is changing in urban slum conditions. When their economical productivity takes priority over their reproductive role, the effects on reproductive decision-making within families may be considerable. This paper highlights the vulnerability of young women as they pragmatically make choices within the social and structural constraints in their lives.

Résumé

Les inégalités structurelles et sociales, l'âpreté de l'économie politique et le manque d'attention de l'État ont fait des adolescentes mariées un groupe extrêmement vulnérable dans l'environnement des bidonvilles urbains au Bangladesh. L'importance accordée àla fécondité des jeunes mariées aboutit à un taux élevé de fécondité et à une faible utilisation de contraceptifs. Une étude ethnographique d'épouses, âgées de 15 à 19 ans, a été réalisée dans un bidonville de Dhaka de décembre 2001 à janvier 2003, avec 50 entretiens approfondis et huit études de cas parmi 153 adolescentes mariées, des observations et des discussions avec des membres de la famille et de la communauté. Les attentes culturelles et sociales ont conduit 128 jeunes femmes à avoir un enfant avant d'y être prêtes psychologiquement ou physiquement. Vingt-sept avaient interrompu leur grossesse, dont 11 forcées par des membres de leur famille. La pauvreté, les conditions économiques, l'insécurité conjugale, les politiques du ménage, l'absence de dot et la rivalité entre la famille, les coépouses et les beaux-parents obligeaient ces jeunes femmes à accepter des décisions prises par d'autres afin de survivre. Le statut des jeunes femmes mariées change dans les bidonvilles urbains. Quand leur productivité économique prendra le pas sur leur rôle reproducteur, les conséquences sur la prise de décision génésique dans la famille pourraient être considérables. Cet article souligne la vulnérabilité des jeunes femmes qui font des choix pragmatiques dans le cadre des limites sociales et structurelles de leur existence.

Resumen

Las desigualdades estructurales y sociales, una severa economía política y el descuido por parte del Estado han hecho de las adolescentes casadas un grupo sumamente vulnerable en los barrios bajos urbanos de Bangladesh. La importancia otorgada a la fertilidad de las jóvenes recién casadas lleva a altas tasas de fertilidad y bajas tasas de uso de anticonceptivos. Desde diciembre de 2001 hasta enero de 2003, en un barrio bajo de Dhaka, se llevó a cabo trabajo etnográfico entre adolescentes casadas, de 15 a 19 años de edad; éste consistió en 50 entrevistas a profundidad y ocho estudios de casos de 153 adolescentes casadas, así como observaciones y conversaciones con sus familiares y miembros de la comunidad. Las expectativas culturales y sociales indicaron que 128 de las jóvenes habían dado a luz antes de estar emocional o físicamente preparadas. 27 habían interrumpido su embarazo; de entre ellas, 11 fueron obligadas a hacerlo por sus familiares. La pobreza, condiciones económicas, inseguridad marital, intrigas en el hogar, ausencia de dote, rivalidad en familia, coesposas y parientes políticos forzaron a estas mujeres a aceptar las decisiones tomadas por otros a fin de sobrevivir. La condición de las mujeres jóvenes casadas está cambiando en los barrios bajos urbanos. El dar más importancia a su productividad económica que a su función reproductiva, influye considerablemente en la toma de decisiones reproductivas en familia. En este artículo se destaca la vulnerabilidad de las jóvenes en su toma de decisiones pragmáticas pese a las limitaciones sociales y estructurales que afrontan.

Structural and social inequalities, a harsh political economy and neglect on the part of the state have made the urban poor in Bangladesh an underclass. Little is known about the synergistic effects of macro-political and economic conditions and social and cultural factors on women's reproductive health experiences and their lives. The study of fertility in anthropology has traditionally centred on its symbolic associations, but anthropologists are increasingly researching these dimensions as well.Citation1Citation2Citation2

Adolescents constitute more than 22% of the population of Bangladesh, 13 million girls and 14 million boys.Citation4 Married adolescent girls in the harsh environment of the urban slums of Dhaka, by virtue of their sex, age and poverty are an extremely vulnerable group. The importance placed on fertility for newly married adolescent girls results in high rates of fertility and low rates of contraceptive use. The current fertility rate of those aged 15–19 is 147 per 1000 girls, ranging from 155 in rural areas to 88 in urban areas. This is the highest fertility rate for this age group in the world. Only about 30% of poor married adolescent girls use a method of contraception, compared to the national figure of 49% for all women.Citation5Citation6 Bangladesh has one of the highest maternal mortality rates in the world, estimated to be 320 per 100,000 live births.Citation7 One consequence of early marriage and childbearing is a higher death rate among adolescent girls than boys aged 15–19, 1.81 as against 1.55 per 1000 population.Citation8

Very little detailed research exists on the factors that shape married adolescent girls' reproductive experiences and behaviour.Citation4 Informed by critical medical anthropology, Footnote1 this paper is about how reproductive behaviour for young women in an urban slum I will call Phulbari (pseudonym) in Dhaka is grounded in the social, political and economic structures of their lives. The rapid influx of rural poor families to Dhaka has led to a rapid increase in urban population growth, slum settlements and worsening poverty. 40–70% of urban population growth is now attributed to rural–urban migration.Citation9Citation10 By 2015, the population of Dhaka is projected to double to an estimated 21 million.Citation11 Urbanisation, rather than being a sign of economic progress, is contributing to the process of under-development and poverty. Almost 60% of the urban poor live in extreme poverty, and the remainder in “hard core” poverty, in which families were surviving on a monthly household income in 1995 of only Taka 2948 (=US$44).Citation10, Footnote2

Urban slum dwellers constituted 30% of the total 14 million population of Dhaka in 2002. Unable to find affordable housing, they lived in insecure tenure, setting up or renting small rooms in shacks with mud floors and bamboo or tin/polythene roofs in settlements built on vacant or disused land on the margins of the city.Citation12 Phulbari was typical. It had a high proportion of squatter households, with most of the poor resettled here after being forcibly evicted in 1975 from different parts of the city.Citation13 The alleyways were tiny and congested, rooms had no fans and drains overflowed with water, sewage and excrement, particularly during the rainy season. Skin infections were rampant. During interviews with young women, I often saw rats and cockroaches run across the floor. They had few possessions, sometimes only a jute mat to sleep on and utensils for cooking.

As slums are considered illegal, they are not entitled to basic government services. In Phulbari, some non-governmental organisations provided tubewells, and the community set up some illegal lines to access piped water. Water was only available for 20–30 minutes, which resulted in long queues, tension and heated exchanges among the women who waited in the hot sun, fighting to get their share. There was electricity but no gas for cooking, so most women burned paper, cloth, plastic or wood to cook on mud stoves. The rent for a room in PhulbariFootnote3 was Taka 200–600 a month (US$3–9).

Methodology

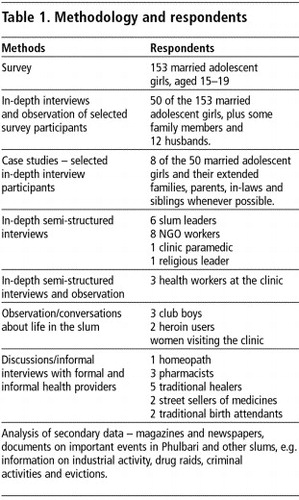

Fieldwork was carried out in sections one, two and four in Phulbari from December 2001–January 2003, using a range of methods and respondents (Table 1). I enlisted the assistance of a research assistant and three health providers who lived and worked in the slum, to identify and locate married adolescent girls aged 15–19. The health providers worked in a well-known international NGO clinic that provided basic reproductive health services to women.Footnote4 The health workers introduced the research assistant and me to leaders of the community who gave us permission to work. Two of the health workers helped us to access married adolescent girls and acted as key informants, validating information collected.

We went door-to-door to find married adolescent girls for the survey, but not all of them were available or agreed to participate. This was particularly the case in areas where drug dens, gang violence, police raids, illegal activities (e.g. selling drugs) and distrust of outsiders made it difficult to visit households systematically, which often determined our access and the time spent with young women, and also made it difficult to ensure rigorous sampling. We tried to select households from the margins as well as the centre of the slum, and those located close to the clinic and further away, to ensure coverage of different sections of the slum. The selection was partly based on opportunistic sampling, i.e. if we found young women available and agreeable to speak to us, we included them in the survey. In addition, we included a few young women who were being treated at the clinic and health providers referred us to a few others. Thus, a total of 153 adolescent girls participated in the survey.

The survey provided information on socio-demographic data, reproductive histories and the young women's experiences of reproductive health and illnesses. It was intended to be exploratory and provide a snapshot of the conditions of life.

Fifty married adolescent girls were selected from those surveyed for repeated in-depth interviews on their reproductive histories, health experiences and life histories. At the same time, eight of the 50 women and their families were selected for longer-term case studies, which meant repeated visits in most cases throughout the fieldwork period till a major eviction took place. After the eviction, eight families and health workers, leaders and some households were traced and followed up until the end of the fieldwork period.

The research process was not linear. We moved back and forth between field observations, repeated in-depth interviews and conversations, case studies and observations. All interviews, field notes and observations were coded into Ethnograph qualitative software and survey interviews analysed with SPSS software.

Findings

Marital relationships of the adolescent girls

Among the 153 adolescent girls, the average age at marriage was 13 years.Footnote5 In Bangladesh, marriage is the only acceptable option for a large part of the population, and allows individuals to have sexual relations without risk of social sanctions. In poor families, marriage is expected to take place soon after a young girl menstruates even though the legal age of marriage is 18 for girls and 21 for boys.Citation15Citation16

Of the 153 girls and their husbands, 49 owned their homes (but lost them in the eviction) and 103 paid rent to a landlord. Twenty-one did not own a bed, but slept on a jute mat on the floor. Some of the rooms were built with a combination of cardboard, bamboo, plastic, newspapers, straw and tin; others had mud floors. Some of the more expensive rooms had cement floors.

Community members and parents commonly said the reason for early marriage was poverty and to avoid the burden of dowry payments.Citation17Citation18Citation19 Dowry payments are illegal but demands for dowry were often still made after marriage. Of the 153 young women, more than 70 young women and their families had paid dowry from Taka 5,000–31,000 at the time of marriage, while 62 had not. Twenty-six young women said their husbands and in-laws had demanded dowry payments after they had married. With increasing urbanisation and insecurity of jobs, a majority of young men and their families saw marriage as a financial investment for the future.

Another reason given by parents for early marriage was the fear that their daughters might be “spoiled” (i.e. through rape or sexual relations) in the slum environment. Many parents believed that a husband would protect their daughter from sexual harassment by slum gang members.

While families often arranged marriages, more than 81 of the 153 young women had a love marriage. Poverty had forced many of them to work outside the home in garment factories where they interacted with young men, resulting in love affairs and marriages, sometimes against the wishes of parents and in-laws. Most of the love marriages in the survey involved little or no dowry. In the honeymoon period the men were not interested in demanding dowry. However, over time, they or their in-laws began to feel cheated and either pushed for the dissolution of the marriage or mistreated the young girl till her family paid them some money.

Marital instability was a widespread concern among the women in the slum and poverty, unpaid dowry demands, unemployment and drug use were all blamed as contributory factors. Of the 153 young women, 17 were already separated or had been abandoned by their husbands. In addition, among the 50 who had in-depth interviews, another seven young women revealed that they had been previously married and that this was their second marriage. Of this group of seven, four were sharing their husbands with a co-wife. Further probing found that another three suspected their husbands had another woman or co-wife.Footnote6 Those who were deserted by their husbands found that working conditions, low wages and social and economic discrimination in the slum and workforce made them worse off than before, a finding supported elsewhere.Citation21Citation22 Young women spoke of the physical insecurity of living alone and the need for a male protector, be it a father, brother, son or fictive “uncle”.

Husbands of the young women

Urban employment for men living in the slums is constrained by lack of qualifications. The only work available tends to be labour intensive, stressful, low paid and at times dangerous.Citation23 Many unskilled labourers remain unemployable or get jobs primarily in the informal labour market. Of the 153 young women surveyed, the husbands of 31 were rickshaw pullers or baby taxi drivers earning Taka 50–150 daily (US$0.74–2.23); 19 were involved in weaving work, earning Taka 500–700 per week (US$7–10); and 19 were working in garment factories, earning Taka 3,000–4,000 per month (US$45–60). The latter work was skilled and highly competitive. More than 15 husbands sold vegetables, fish or fruit around the slum neighbourhood, earning Taka 40–50 (US$0.60–0.75) on a good day. However, profits varied seasonally; unsold goods rotted quickly, and goods were sold at cheaper prices to get rid of stock. The rest of the men were day labourers, earning Taka 100 per day (US$1.50), cooks, car drivers or mechanics.

Initially, 29 young women reported that their husbands did not work regularly or were periodically unemployed. Further probing found that more than 53 of the 153 women worked off and on doing sewing or in the garment factoryFootnote7 to support their families, which suggests that the number of men not working consistently was much higher. This shift in the culturally accepted roles of men as rice-winners and women as homemakers was having an impact on gender relations, creating tensions in the household. Of 153 young women, 89 said they experienced regular to occasional domestic violence as a result.

Twelve young women said their husbands were heroin users, or addicted to alcohol and gambling. Observations revealed that drug use and gambling were common problems among young men in the slum. Added to this was the prevalence of gang violence. Virtually every slum is neglected by the government, and has its own leadership structure and gangs. Of the 50 in-depth interviews, at least four husbands were or had been gang members. One, a well-known gang member, had been killed in 2001, one had been left disabled after a fight, and the other two were known as troublemakers locally.

Many of the adolescent married women tolerated their husband's behaviour. “Men can marry ten times and no one comments, but if a woman marries even twice, everyone will talk. That is why we stay with the man!” Scarce resources affected the support young women could rely on from their natal families. Narratives were laced with comments such as “one needs to manage on one's own” and “you can't rely on anyone, including your own family these days”. All of these factors played a critical role in the young women's reproductive decisions and health.

Having a baby early or not: benefits and costs

Browner notes that much of the literature assumes that men and women share similar reproductive interests, but this is not always the case.Citation24 In Phulbari, reproductive interests differed between young women and their husbands, in-laws and mothers.

Married adolescent girls valued and wanted children and also realised that social acceptance and security in the marital home were established largely through fertility, particularly the birth of a son.Footnote8 Of the 153 women surveyed, 123 said they felt compelled to bear one or more childrenFootnote9 soon after marriage, when they were not yet ready. There were strong pressures to prove their fertility as soon as possible. Children were valued for bringing happiness to a household and increasing the emotional bond between a husband and wife, and ensured marital and economic security for young women – at least these were the hopes.

Shohagi,Footnote10 aged 14, had a love marriage and a baby was the only way she could improve her relationship with both her husband, who wanted a child, and her in-laws, who did not accept her.

“My husband and I had a love marriage. Soon after the marriage he started talking about children but I didn't feel ready but he really wanted a baby. I was working in the garments. I wanted to work for longer, save up some money and then have a child… My mother convinced me to have a baby to make him happy.” (Shohagi)

“My son-in-law would not work and they were always fighting. His parents started taking advantage of this situation and started demanding dowry money. Her husband would gamble and beat her up. He wouldn't feed her rice properly. But after the birth of the child, everything changed…” (Shohagi's mother)

“My mother said that it was the only way to make him more responsible and make the marriage stronger… After my first daughter was born his maya [love] increased for me… He is pleased with me and he gives me whatever I need. Before he would give his brothers and sisters his income, but now he gives me his income. If you have a child, sister, you can exercise your rights but if you don't have a child then you have no rights.” (Shohagi)

Once a woman has produced a child, even a daughter, a new phase in her life begins. The literature shows she can often initiate separation from the joint household, and she may gain greater domestic power and decision-making.Citation17 Many of the young women shared Shohagi's experience. In the in-depth interviews and cases studies, it was apparent that some of the men had close and loving relationships with their children and played an important role in their lives, even if they left their wives and remarried or relocated. Many of the young women hoped that children would ensure continued emotional ties and financial support for the household, even if the marriage broke down. Many of them spoke of their children as evidence of an obligation fulfilled, which ideally should ensure them greater rights in relation to their husbands.

Still, there was anxiety surrounding childbearing in the slum. While many of the 153 surveyed women saw it as a pragmatic decision, 27 reported that they had terminated a pregnancy, of which 13 had sought menstrual regulation servicesFootnote11 and 14 had had unsafe abortions. Some of these 27 had already given birth to one child and spoke of the difficulties of looking after another. Many of them, while not using family planning regularly, had incorporated the rhetoric of family planning campaigns, which link smaller families to better economic conditions and quality of life. On probing, we found that 11 of the 27 were coerced into aborting their first pregnancy, either by husbands, in-laws or co-wives. Extreme deprivation, rivalry over resources and asymmetrical relationships ensured that these women had few options to resist such demands.

No earnings, no baby!

Bina, a 17-year-old adolescent woman, fell in love and married a co-worker from the garment factory, who was 20. The marriage took place despite her parents' anger and protests. They were unable to stop the marriage as they lived in the village and Bina was independent, earning her own income and living in the city with her uncle. Although her in-laws did not protest about the marriage she knew they were not happy because she had not paid any dowry to her husband. They settled comfortably into married life and lived in her in-laws' home in the slum. After six months of marriage, Bina fell pregnant:

“A couple of months after my marriage I began to feel weak and tired all the time. The doctor did a check-up and informed me that I was pregnant. When we were leaving the clinic, my husband said, ‘Let's not keep the child, you are not well at all. You look so sick.' My grandmother-in-law brought medicine [abortion medicine] from the local healer …[voice shaking] my father-in-law wants me to work and bring money for the household. If I fall pregnant I cannot work, can I? …She brought the [indigenous] medicines the very next day, but when nothing happened, my father-in-law spoke to the health workers about a possible MR. I overheard them discussing the costs of the MR… I thought to myself what is the point of me saying anything. My father-in-law has no intention of letting me keep the baby. If I don't listen to him, I will have to suffer and hear words. Then who will feed the baby if no one wants the baby in the household? I felt very sad initially. It was our first child… When I got married and I came to this home my father-in-law said to me, ‘You have to work for two years and give me all your earnings… Well, if he had got his son married he could have got Taka 50,000 for him in dowry money so I have to make up for it. He does not misbehave with me though… I was upset but what can he [husband] do. We live at my father-in-law's place and he provides us a roof over our heads. I have married him now and my parents have nothing to do with me. It is better that I keep quiet and do what my in-law thinks is best…”

A few of the young women resisted such pressures. Rashida, 16 years old, lived with her husband in her in-laws' home. Like Bina, she also had a love marriage and did not pay any dowry at the time of marriage. When her in-laws found out she was pregnant they insisted she terminate it but she refused. Rashida's husband did not work regularly and her in-laws wanted her to continue working at the garment factory and provide for the family, but she stopped working five months into her pregnancy. Her husband and in-laws' reliance on her income meant that they saw little or no personal gain from her having a child in the immediate future. As a result, when she suffered from serious labour complications during her pregnancy, neither her husband nor her in-laws felt obliged to contribute towards her treatment costs. Rashida said: “In the end it was the neighbours who brought my mother, and it was mother and my older brother who spent Taka 5,000 (US $75) and took me to the hospital.” Afterwards, she continued to be subjected to verbal and physical abuse.

Thus, these young women's economical productivity took priority over their reproductive role, which did not have the same value and status it once had because they were able to work and earn an income and contribute to the household.

Polygamy and co-wives: jealousy, insecurity and manipulation

Marital instability, anxiety over husband's fidelity and the presence of co-wives aggravated feelings of insecurity among the women and shaped their reproductive behaviour. In polygamous households, competition for resources is greater than in other households. Observations in the slum revealed that rivalries with co-wives over finances as well as the insecurity of wanting to strengthen emotional and sexual ties with husbands led some co-wives to try for a baby soon after marriage. This was the case of Dolly, 15 years old, who was her husband's second wife. He was still married to his first wife and had two children, and maintained close relations with them. Dolly was four months pregnant at the interview.

“See, I am nothing to him. But if I have a child he will have to buy it milk. He buys those children [from first wife] milk but he does not make a big deal of it, but when it comes to me it is a different story! I am not going to get rid of this child…”

Her husband pleaded with her not to have the baby because of financial constraints, and Dolly ended her pregnancy soon after this meeting. She was upset that because her husband already had children he was not interested in supporting another child. She initially purchased some pills from the pharmacy but when they did not work, she asked her husband to pay for a menstrual regulation from the local clinic. She was so upset after the termination that she moved out of her husband's home and moved in with her elder female cousin, who also lived in the slum. Her husband begged her to return to him, but when we last saw her, she was still refusing.

Maliya, 14 years old, had been married for less than a year and was caught in the politics between her father-in-law's two co-wives. Maliya's husband's stepmother arranged their marriage, but soon after the marriage, Maliya moved with her husband into his own mother's home but remained close to her father-in-law's much younger second wife. Her husband's mother constantly harassed her, she believed, due to jealousy. When Maliya fell pregnant, her mother-in-law insisted that she terminate her pregnancy, citing her young age as a great risk factor. In addition, Maliya's husband did not support her decision to continue the pregnancy and sided with his mother. Since Maliya lived in the first mother-in-law's home, the father-in-law and his second wife did not interfere for fear of antagonising the first wife and her sons. Maliya's parents also did not want to interfere. Private discussions with Maliya's mother-in-law, Sufia, revealed underlying tensions about her co-wife and daughter-in-law and her insecurity about losing control over her son:

“Maliya did not want to abort the child but my son was not agreeable to this. I thought she was too young. He felt he was too young and it was too soon for them to have children. This son of mine did not want to get married. He did not like her. That woman [co-wife] picked her out for my son. Why did she want a child immediately? It would trap my son. She would be able to hold on to my son. If she gave him a baby boy, he would listen to her and she could do what she wanted…”

Maliya's mother-in-law, Sufia, feared her position was shaky, as her husband's second wife was much younger and had already had a baby boy. Sufia only had her two sons to rely on for her future economic and social security. Despite the fact that her husband owned numerous small grocery stores in the slum and land in the village, under Islamic law, a mother only inherits one-eighth of her husband's property if she is widowed. Her two sons, and any children the second wife bore, would inherit almost all of her husband's property. Since her husband's remarriage, she appeared anxious about losing control over her sons, who were her only remaining support.

The literature illustrates that widows and women without sons are at greater risk of illness and poverty, with their only recourse begging or death.Citation18Citation19Citation29 Sufia was anxious that if Maliya had a baby her son would shift his affections to her and the newborn infant. This would automatically result in the transfer of his finances to the needs of his own family. While Sufia still had power over household matters, she would continue to act in her own best interests, even if it harmed her daughter-in-law's.

Conclusion

Struggles over termination of a pregnancy provide an insight into the complex inter-relationships between structural conditions, political–economic conditions and gender and power inequalities, which shape the nature of relationships between newly married girls, their husbands and extended family, and impact on reproductive choices.

When we talk about reproductive health and rights we have certain notions about women's autonomy over their bodies and their lives, including the right to decide the number of children to bear and the right to continue a pregnancy or not. As Petchesky notes, however, often poor women may go along with decisions not of their own making, which may violate their sense of bodily integrity and well-being, but with the hope of gaining some advantage in the context of limited options.Citation30 This paper illustrates how the politics of individual reproductive decision-making has a strong connection to larger socio-cultural, political and economic inequalities and familial relationships in the lives of married adolescent girls. Although many of the girls were compelled to bear children before they were ready, they recognised the advantages of doing so, while others were forced to terminate pregnancies whose advantages to themselves put others at a disadvantage.

Poverty, economic conditions, marital insecurity, politics in the household, absence of dowry and rivalry among family, co-wives and in-laws made these young women acquiesce to decisions made by others in order to survive. Young married women's status is changing in urban slum conditions. When their economical productivity takes priority over their reproductive role, the effects on reproductive decision-making within families may be considerable. This paper highlights the vulnerability of young women as they pragmatically make choices within the social and structural constraints in their lives.

Acknowledgements

This study (Project A 15054) was supported financially by the Special Programme of Research, Development and Research Training in Human Reproduction, World Health Organization, Geneva. I would like to thank all the married adolescent girls and their families for their time, kindness and patience. I am grateful to Nipu Sharmeen, research assistant, for her valuable assistance during fieldwork. I would like to thank Dr Diana Gibson, Amsterdam University, for her critical feedback and valuable comments, which improved the paper. I am also grateful to Dr. Andrea Whittaker for her constant support throughout my PhD. This paper is drawn from my PhD thesis in medical anthropology/public health, Australian National University, Canberra, Australia, 2005.

Notes

1 Disease is understood in critical medical anthrology as being social as well as biological, with a focus on the links between disease and social class, poverty, power and ill-health, i.e. the political economy of health.Citation14

2 US $1 = Taka 67 BDT.

3 Although slums are considered illegal, there are informal governance structures with local leaders controlling land and residents paying rent.

4 To join the clinic cost women Taka 25 (=US $0.37), which included a certain amount of free medicines. The following services were listed as being provided: general health, family planning, antenatal care (iron tablets, injections), care for reproductive and sexually transmitted illnesses, urine pregnancy tests and free immunisation services for infants. Menstrual regulation was available at the clinic's headquarters.

5 Approximately 75% of girls in Bangladesh are married before the age of 16. Only 5% are married after the age of 18, the legal age of marriage.Citation20

6 The extent of actual marital breakdown is uncertain because of the social stigma attached. The few studies available suggest that migration from the village to urban slums disrupts the extended family system, causing instability.Citation15

7 More than two million people work in the garment sector nationally, of which 80% are women.Citation20

8 In rural areas of Bangladesh sons are valued above daughters for their economic value and in carrying on the family line.Citation25Citation26Citation27

9 Available literature in Bangladesh suggests that 30% of adolescent girls are already mothers and another 6% are pregnant with their first child.Citation20

10 All the names of respondents have been changed to respect confidentiality.

11 In rural and urban Bangladesh, although abortion is legally restricted, menstrual regulation (MR) services are widely available from both public and private sector clinics, although some untrained providers are still operating.Citation28

References

- S Greenhalgh. Controlling births and bodies in village China. American Ethnologist. 21(1): 1994; 3–31.

- S Greenhalgh. Situating Fertility: Anthropology and Demographic Inquiry. 1995; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge.

- K Kielmann. Barren ground: contesting identities of infertile women in Pemba, Tanzania. M Lock, PA Kaufert. Pragmatic Women and Body Politics. 1998; Cambridge University Press. 127–164.

- Q Nahar, S Amin, R Sultan. Strategies to Meet the Health Needs of Adolescents: A Review. Operations Research Project, Health and Population Extension Division. 1999; ICDDR,B: Dhaka.

- SE Arifeen, S Mookherjee. The Urban MCH–FP Initiative (A Partnership for Urban Health and Family Planning in Bangladesh): An Assessment of Programme Needs in Zone 3 of Dhaka City. 1995; ICDDR,B: Dhaka.

- Bangladesh Demographic and Health Survey 1999–2000. National Institute of Population Research and Training, Mitra and Associates, Dhaka. 2000; ORC-Macro International: MD.

- GOB-UN. Millennium Development Goals, Bangladesh Progress Report 2005. 2005; Government of Bangladesh – UN: Dhaka.

- Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics. Health and Demographic Survey: Population, Health, Social and Household Environment Statistics 1996. 1997; Ministry of Planning: Dhaka.

- G Wood. Desperately seeking security in Dhaka slums. Discourse: A Journal of Policy Studies. 2(2): 1998; 77–87.

- N Islam, N Huda, FB Narayan. Addressing the Urban Poverty Agenda in Bangladesh: Critical Issues and the 1995 Survey Findings. 1997; University Press Limited: Dhaka.

- H Perry. Health for All in Bangladesh. Lessons in Primary Health Care for the 21st Century. 2000; University Press: Dhaka.

- N Islam. The Urban Poor in Bangladesh. 1996; Centre for Urban Studies: Dhaka.

- R Afsar. Rural–Urban Migration in Bangladesh. 2000; University Press Limited: Dhaka.

- HA Baer, M Singer, J Johnsen. Towards a critical medical anthropology. Social Science and Medicine. 23(2): 1986; 95–98.

- S Jesmin, S Salway. Policy arena. Marriage among the urban poor of Dhaka: instability and uncertainty. Journal of International Development. 12: 2000; 698–705.

- ME Khan, JW Townsend, S D'Costa. Behind closed doors: a qualitative study of sexual behaviour of married women in Bangladesh. Culture, Health & Sexuality. 4(2): 2000; 237–256.

- Stark NN. Gender and therapy management: reproductive decision making in rural Bangladesh. PhD thesis. Southern Methodist University, USA, 1993.

- TA Abdullah, S Zeidenstein. Village Women of Bangladesh: Prospects for Change. 1982; Pergamon Press: Oxford.

- S Lindenbaum. The Social and Economic Status of Women in Bangladesh. 1974; Ford Foundation Report: Dhaka.

- A Barkat. Adolescent Reproductive Health in Bangladesh. Status, Policies, Programs and Issues. 2003; Policy Project: Dhaka.

- N Kabeer. Gender Dimensions of Rural Poverty: Analysis from Bangladesh. IDS Discussion Paper 255. 1989; Institute for Development Studies: Brighton, 241–262.

- N Kabeer. Reversed Realities: Gender Hierarchies in Development Thought. 1995; Verso: London.

- A Kabir. Shocks, vulnerability, and coping in the Bustee communities of Dhaka. Discourse: A Journal of Policy Studies. 2(2): 1998; 120–146.

- C Browner. Situating women's reproductive activities. American Anthropologist. 102(4): 2001; 773–789.

- M Cain. The economic activities of children in a village in Bangladesh. Population and Development Review. 4(1): 1977; 23–80.

- Barkat-e-Khuda. Value of children in a Bangladeshi village. JC Caldwell. The Persistence of High Fertility: Third World Population Prospects. 1977; Australian National University: Canberra.

- JC Caldwell, AKM Jalaluddin, P Caldwell. The changing nature of family labor in rural and urban Bangladesh: implications for fertility transition. Canadian Studies in Population. 11(2): 1984; 165–198.

- Akhter HH, Provision of Services by Mid-level Providers and Counselling for the Provision of Manual Vacuum Aspiration (MVA)- (Safe Abortion) – Bangladesh Experience. Unpublished report. Dhaka: BIRPERHT, 2000.

- O Rahman, A Foster, J Menken. Older widow mortality in rural Bangladesh. Social Science and Medicine. 34(1): 1992; 89–96.

- RP Petchesky. Re-theorizing reproductive health and rights in the light of feminist cross-cultural research. CM Obermeyer. Cultural Perspectives on Reproductive Health. 2001; Oxford University Press: Oxford, 277–300.