Abstract

The Women's Right to Life and Health project aimed to reduce maternal morbidity and mortality in Bangladesh through provision of comprehensive emergency obstetric care (EmOC) in the country's district and sub-district hospitals. Human resources development was one of the project's major activities. This paper describes the project in 2000–2004 and lessons learned. Project documents, the training database, reports and training protocols were reviewed. Medical officers, nurses, facility managers and laboratory technicians received training in the country's eight medical college hospitals, using nationally accepted curricula. A 17-week competency-based training course for teams of medical officers and nurses was introduced in 2003. At baseline in 1999, only three sub-district hospitals were providing comprehensive EmOC and 33 basic EmOC, mostly due to lack of trained staff and necessary equipment. In 2004, 105 of the 120 sub-district hospitals had become functional for EmOC, 70 with comprehensive EmOC and 35 with basic EmOC, while 53 of 59 of the district hospitals were providing comprehensive EmOC compared to 35 in 1999. The scaling up of competency-based training, innovative incentives to retain trained staff, evidence-based protocols to standardise practice and improve quality of care and the continuing involvement of key stakeholders, especially trainers, will all be needed to reach training targets in future. © 2006 Reproductive Health Matters

Résumé

Le Projet sur le droit des femmes à la vie et la santé souhaitait réduire la mortalité et la morbidité maternelles au Bangladesh en fournissant des soins obstétriques d'urgence complets dans les hôpitaux de district et de sous-district. L'une de ses principales activités était le développement des ressources humaines. Cet article décrit le projet en 2000–2004 et ses enseignements. Il a examiné les documents du projet, la base de données sur la formation, les rapports et les protocoles de formation. Les cadres médicaux, les infirmières, les administrateurs des centres et les techniciens de laboratoire ont été formés dans les huit hôpitals des écoles de médecine du pays, avec des curricula nationaux. Un cours de 17 semaines a été introduit en 2003 pour les équipes de cadres médicaux et d'infirmières. En 1999, seuls trois hôpitaux de sous-district fournissaient des soins obstétricaux d'urgence complets et 33 des soins obstétricaux d'urgence de base, principalement faute de personnel qualifié et d'équipement. En 2004, 105 des 120 hôpitaux de sous-district dispensaient des soins obstétricaux d'urgence, 70 complets et 35 de base, alors que 53 des 59 hôpitaux de district assuraient des soins complets, contre 35 en 1999. Pour atteindre les objectifs de la formation, il faudra accélérer la formation basée sur l'acquisition de compétences, créer des encouragement novateurs pour retenir le personnel formé, définir des protocoles fondés sur les données pour normaliser la pratique et améliorer la qualité des soins, et garantir la participation suivie des acteurs clés, particulièrement des formateurs.

Resumen

El objetivo del proyecto Derecho de las Mujeres a la Vida y la Salud era disminuir las tasas de morbimortalidad materna en Bangladesh mediante la provisión de cuidados obstétricos de emergencia (COE) integrales en los hospitales de distrito y sub-distrito. El desarrollo de recursos humanos fue una de las actividades principales. En este artículo se describe el proyecto de 2000–2004 y las lecciones aprendidas. Se revisaron los documentos del proyecto, base de datos, informes y protocolos de capacitación. Los funcionarios médicos, enfermeras, administradores y técnicos recibieron capacitación en los ocho hospitales de las facultades de medicina del país. Para ello, se usaron currículos aceptados nacionalmente. En 2003, se lanzó un curso de 17 semanas de duración de capacitación basada en competencia para funcionarios médicos y enfermeras. En 1999, debido a la falta de personal capacitado y de equipo necesario, los COE integrales eran proporcionados en tan sólo tres hospitales de sub-distrito; los COE básicos en 33. En 2004, 105 de los 120 hospitales de sub-distrito eran funcionales para los COE, 70 con COE integrales y 35 con COE básicos, mientras que 53 de 59 de los hospitales distritales estaban proporcionando COE integrales comparado con 35 en 1999. Para lograr los objetivos planteados se necesitará la ampliación de la capacitación basada en competencia, incentivos innovadores para retener al personal capacitado, protocolos basados en evidencia para estandarizar la práctica y mejorar la calidad de la atención, y la continua participación de las partes interesadas clave, especialmente los capacitadores.

Maternal mortality is unacceptably high in Bangladesh, where an estimated 16,000 women die annually from complications of pregnancy and childbirth.Citation1Citation2Citation3Citation4 Availability of and access to emergency obstetric care (EmOC) is essential to save women's lives when complications occur.Citation5

The first initiatives in Bangladesh to strengthen EmOC were undertaken by the government at 86 sub-district hospitals in 10 districts, under the Directorate General of Health Services, through implementation of the Maternal and Neonatal Health CareCitation6 and Thana Functional Improvement Pilot Projects in 1993–98. Since 1993, UNFPA has been supporting activities to strengthen 64 maternal and child welfare centres for EmOC, under the Directorate General of Family Planning.Citation7 In addition, in 1994–98, with the support of UNICEF, the Obstetrical and Gynaecological Society of Bangladesh improved EmOC in 11 district hospitals on a pilot basis, with subsequent expansion to other districts. Interventions in these projects included renovation of maternity units and operating theatres, supply of equipment and drugs and human resources development. Human resources development activities included in-service training of medical officers in obstetrics and anaesthesia, nurses in midwifery, and laboratory technicians in safe blood transfusion. Medical officers in Bangladesh hold an MBBS degree and provide general care at all levels of health facility, in both urban and rural areas.

Obstetric services at district hospitals, particularly the treatment of complications, primarily depend on consultants who hold a postgraduate obstetrics degree. Consultants in anaesthesia are likewise required for surgical interventions. Consultants are mostly not available at sub-district hospitals, limiting the availability of most emergency obstetric interventions. Medical officers, the only doctors at sub-district level, had not received adequate training or practical experience to provide EmOC independently.

Initially, medical officers were trained in Nepal under the Maternal and Neonatal Health Care project. Subsequently, curricula were developed and the training was organised at medical college hospitals in Bangladesh. Training of medical officers was originally designed as a six-month course but was later extended to one year. Similarly, training of nurses was extended from six weeks to four months. Laboratory technicians participated in a two-week training course. In total, 92 medical officers, 107 nurses and 35 laboratory technicians were trained over six years. However, management, monitoring and coordination were found to be inadequate for the large number of service providers in need of in-service training.

In preparation for the project described here, a national baseline survey to assess the availability of EmOC was conducted in 1999.Citation9Citation10 Information was collected from 13 public medical college hospitals, 59 district and 104 (out of 400) sub-district hospitals, 62 maternal and child welfare centres and 224 private clinics/hospitals nationwide. The study showed that basic and comprehensive emergency obstetric careFootnote1 were not available at 26% of district and 65% of sub-district hospitals. Non-availability of services was mostly related to lack of adequately trained personnel, either in obstetrics or anaesthesia or both, along with lack of equipment and infrastructure.

The Women's Right to Life and Health project, implemented by the Directorate General of Health Services, is a joint collaboration between the Government of Bangladesh, UNICEF and the Averting Maternal Death and Disability Programme at Columbia University. It aims to contribute to the government's goal of reducing maternal mortality and disability related to pregnancy and childbirth. The project started in July 2000 and was designed to improve the availability, quality and use of comprehensive EmOC by strengthening the capacity of all 59 district hospitals and 120 of the 400 sub-district hospitals nationally.Citation11

The average district and sub-district populations are about 2 million and 200,000, respectively.Citation8 Among the estimated 3.5 million births annually (1999),Citation2 more than half a million women (or an estimated 15% of the totalCitation12) were likely to experience complications during pregnancy or childbirth.Footnote2

Major project interventions included renovation of facilities, in-service training of medical officers, nurses and laboratory technicians, supply of necessary equipment and logistics, including strengthening of the health management information system, improvement of emergency readiness and quality of care. Community and social mobilisation activities, such as observation of Safe Motherhood Day, distribution of posters and leaflets, and strengthening of facility-based health education were also undertaken.Citation10

Implemented by the Directorate General of Health Services, training activities were designed to increase skills of medical officers, nurses and laboratory technicians, and management capacity. This paper describes the lessons learned during this project from 2000 through 2004.

Data sources

Documents reviewed for this study included project reports, the current project proposal, the training database and bimonthly facility update reports. Trainee performance reports completed by the focal points from the training institutions, monitoring reports from trainers and project staff, and meeting minutes of periodic reviews were also reviewed. Human resources development protocols such as training manuals for medical officers, nurses, laboratory technicians and managers were analysed. A checklist was developed for monitoring visits to training facilities to capture information such as trainees' performance, lecture classes, opportunities for skills practice, training facility caseload, number of other trainees in the department, training problems and general observations recorded in reports. The first author was the technical officer for human resources development in this project. Information was also collected from the Deputy Programme Manager, Dr Md. Nazrul Islam, Reproductive Health Programme, Directorate General of Health Services.

Human resources development activities

Human resources development activities were aimed at having at least two medical officers (one each in obstetrics and anaesthesia) and four nurses at designated sub-district hospitals and five nurses at district hospitals, all with improved skills for EmOC. To meet this target, 336 medical officers, which included a 40% reserve for attrition, and 775 nurses were to be trained. Most of the training took place at eight medical college hospitals throughout Bangladesh using existing curricula.

Mid-way through the project, a new competency-based training programme was introduced to train providers in teams, using a shorter, more intensive curriculum. Training of laboratory technicians for safe blood transfusion was also addressed. In addition, an orientation programme for facility managers was developed to improve understanding of technical and managerial issues involved in supporting readiness to respond to obstetric emergencies.

The curricula for medical officers, nurses and laboratory technicians were developed by groups of experts from the respective fields, and reviewed by professionals from the medical college hospitals and programme personnel before approval by the National Curriculum Review Committee. There was no formal training of trainers for the focal points or heads of departments for the regular training. However, one-day orientations were held on the curricula before placement of trainees at the medical college hospitals.

One-year training for medical officers

The curriculum for medical officers in obstetrics included skills for conducting normal deliveries, management of antepartum and postpartum haemorrhage, complications of abortion, toxaemia of pregnancy, manual removal of placenta, assisted vaginal delivery and caesarean section, including cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Training of medical officers in anaesthesia included local/regional, spinal and general anaesthesia and cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Trainees were guided by a focal point from their respective departments, who implemented and monitored the training. Trainees observed and assisted the senior doctors in the first three months. In the next three months, they practised under supervision and during the last six months they performed independently. Lectures were at regular intervals, mostly during the first six months, to cover the relevant theoretical concepts. To track skills practice, minimum performance targets were established for each of the emergency obstetric and anaesthetic functions. Trainees maintained a logbook to record their activities. The focal point and head of the department checked the logbook monthly to monitor performance and progress.

Review of training logs and monitoring reports showed that for medical officers in anaesthesia, there was plenty of opportunity for skills practice and they usually exceeded their performance targets. Strong commitment of the anaesthesia departments to the training programme, as well as low numbers of other trainees working in them, appear to have contributed to successful training.

For medical officers training in obstetrics, practical opportunities were mostly adequate but the large number of other trainees (postgraduate and in-service) in the department did limit practice opportunities, even with a year-long placement. In one medical college hospital, low caseload was a factor in not meeting targets. The lecture classes in the one-year course were held but often not as scheduled in the curriculum. Training targets were met for most skills except peripartum hysterectomy, manual vacuum aspiration and assisted vaginal delivery, specifically vacuum extraction. Low caseloads for peripartum hysterectomy and trainer perception that it was too risky for trainees to perform the procedures were barriers. In the case of manual vacuum aspiration and vacuum extraction, a lack of routine practice of these procedures at the medical college hospitals limited skills modelling and practice for trainees.

Midwifery training for nurses

The nurses' training was organised by the nursing institutes and nurses were placed at the attached medical college hospitals for practical, hands-on training. The training course for nurses included management of normal labour, nursing care of obstetric patients, operating theatre management, infection prevention and assisting medical officers with emergency obstetric cases, including surgery. In addition to practical learning in the wards, the course included lectures to cover theoretical aspects. Performance targets and training logs were maintained and as with medical officers' training, nurses' training was also supervised and coordinated by a focal point.

It was found that nurses often faced resistance from doctors to their taking part in manual vacuum aspiration and manual removal of placenta, and in some cases even in normal deliveries. They were also not easily allowed to act as first assistant during obstetric surgery. This appears to be due to negative attitudes of doctors toward nurses and a large number of trainee doctors in the department. However, most of these problems were resolved after repeated discussions in the Training Coordination Committee meetings and through external monitoring.

Trainees' skill acquisition was evaluated through mid-term and final examinations. Trainees received their training certificate when their knowledge and skills were satisfactory, as evaluated by departmental teachers. A post-training evaluation showed that 87% of medical officers and nurses felt confident of providing comprehensive EmOC after training.Citation13

Safe blood transfusion

Laboratory technicians were trained in blood grouping, cross-matching and screening of blood for syphilis, hepatitis B and C, malaria and HIV, including selection of donors and drawing of blood for transfusion. This course also had performance targets and the training was monitored by the head of the Safe Blood Transfusion Department or his assigned teaching staff.

Laboratory technicians were found to have received satisfactory training at the medical college hospitals. However, a major challenge was to ensure an adequate supply of reagents and supplies, including blood bags, at EmOC facilities, especially at sub-district hospitals.

Competency-based training for emergency obstetric care teams

Competency-based training was introduced mid-way through the project for teams of medical officers and nurses from designated facilities, covering evidence–based practices for normal delivery as well as EmOC. Competency-based training in anaesthesia for medical officers was also included. A team training approach was adopted.Citation14Citation15Citation16

The introduction of this new teaching methodology began with two regional workshops bringing together clinical and training experts from JHPIEGO, the Averting Maternal Death and Disability Programme and six South Asian countries, to review and finalise the curricula. Several meetings were then held in Bangladesh to generate commitment from Ministry of Health and Family Welfare officials, training centre managers, professors and professional organisations to the new training programme.

In late 2002, a regional training-of-trainers course was organised over a three-month period for teams of trainers, with two teams from Bangladesh participating. The training of trainers was conducted by JHPIEGO with master trainers from the USA, UK, India and Nepal. The training of trainers was held in Bangladesh at the Dhaka Medical College Hospital and Maternal and Child Health Training Institute, Dhaka. The Bangladesh team included two obstetricians, two anaesthesiologists and three nurses from these sites.

Modelling of skills and good quality care at the training sites are essential for competency-based training. The training of trainers included three weeks for knowledge and skills update and two weeks for clinical training skills, with follow-up and coaching provided between sessions. In addition, site strengthening was an important component of implementing this course, with assessments of the training facilities conducted using checklists from the course materials. Findings were used to improve the set-up and organisation of services, use of standard protocols and evidence-based practices, particularly for manual vacuum aspiration, assisted vaginal delivery and infection prevention practices, supply systems for essential drugs and supplies and improved patient flow.

The competency-based training course was introduced to accelerate the output of trained medical officers by reducing the duration of training from one year to 17 weeks, using the team approach. The objective was to institutionalise competency-based training. In the period reported here both the one-year and competency-based courses were conducted, with previously untrained medical officers and nurses enrolling in one or the other. Three training batches were completed during 2003 and 2004.

The course begins with three weeks of theoretical classes on current evidence-based practices, including practice of clinical skills on anatomic models, followed by initial skills practice under supervision and then independently at the training sites. The course focuses on the specific knowledge, skills and attitudes needed to conduct normal deliveries and perform EmOC functions in a standardised way, as well as skills for inter-personal communication. The course also includes skills for basic newborn care and assessment, as well as newborn resuscitation. The curriculum is based on the WHO manual Managing Complications in Pregnancy and Childbirth.Citation17 Detailed

checklists are used throughout the course to guide and assess standardised skills development, and participants maintain a logbook throughout. Trainers conduct follow-up visits at the trainees' places of posting within six months of completion of training for mentoring and evaluation.The competency-based training curriculum in obstetrics is similar to that of the one-year training course, except for peripartum hysterectomy. The one-year course in anaesthesia includes intubation and general anaesthesia, while the competency-based training teaches only spinal and ketamine anaesthesia along with management of complications and adult and newborn resuscitation.

The competency-based training methodology offers a more structured and compact course in skills for obstetric care and anaesthesia. This has implications both for the volume of training, since several courses could be completed each year, as well as for the amount of time that medical officers are away from their designated posts. Use of anatomic models was found to be an effective tool for skills transfer, and providers were interested in their use. The step-by-step checklists were also found to be effective for learning procedures as well as assessment of skills. Training nurses and doctors together reinforced the importance of teamwork in responding to emergencies. The site strengthening process in support of competency-based training was valuable in highlighting the importance of modelling and addressing deficits, such as infection prevention practices, and use of evidence-based techniques for case management.

While two training teams were originally developed for competency-based training, loss of two of the three obstetrics trainers to private organisations led to consolidation of trainers into one team. Only three courses for service providers were completed in the two years, due to time constraints on the trainers, who also had other responsibilities in the medical college hospitals. Trainers would need to be able to dedicate more time to training and follow-up visits for the programme to be successful. The presence of a large number of other trainees at the training sites was also a limiting factor for skills practice.

Trainee selection, placement and retention

The Reproductive Health Programme Manager of the Directorate General of Health Services selected the medical officers for training through interview, while nurses and laboratory technicians were selected directly from the designated facilities where they were working. Medical officers, nurses and laboratory technicians selected for the training did not necessarily have any previous experience in EmOC. Medical officers from any facility could apply for training and be transferred to a designated facility before training placement. Medical officers and nurses selected for the training commit to a bond period following training in which they are required to serve at designated facilities. The bond period was originally three years, but was shortened to two years in 2002 by the project's core committee. Providers were not allowed to transfer to non-designated facilities, as there might not be the infrastructure and other trained staff available to provide full EmOC. They were also not allowed to pursue post-graduate education during the bond period.

Trainees were provided with a monthly scholarship, book grant, travel allowance and training materials. On successful completion of training, they received a certificate. The one-year training of medical officers is recognised by the Bangladesh Medical and Dental Council. Thus, it could be counted towards specialised degrees in future. Non-monetary incentives, such as preference for in-country and foreign training, annual award and preference for higher education were based on satisfactory service.

One of the major challenges in this project was to attract more medical officers for training in anaesthesia, as well as female medical officers for training in obstetrics. Less than a quarter of the medical officers trained in obstetrics were women. Family decision-makers might expect there to be a female medical officer to attend women with obstetric complications.

The bond period was a disincentive for training to some but is programmatically important to avoid misuse of training resources. Not wanting to work in remote rural areas was a common limitation to attracting medical officers to the training. Other limiting factors were low morale among staff working in overcrowded and often under-equipped public facilities, as well as lack of a clear path for career advancement following training. Work in a hardship post such as a rural hospital is not generally recognised or rewarded. The incentives offered in this project helped to draw some trainees, but more innovative ideas are needed.

The overall attrition rate, both within and after the bond period, was about 35% (about 10% within the bond period). Close monitoring and stronger commitment is required to retain trained medical officers at designated facilities, as many medical officers got themselves transferred to non-designated facilities in more desirable locations, or left for advanced degrees. The amount of time required to transfer medical officers to a designated facility before placement for training was found to be too long as well. The transfer process was streamlined from a 5–6 month process to 2–3 months, with a single transfer order for all the medical officers in a training batch.

Training coordination and monitoring

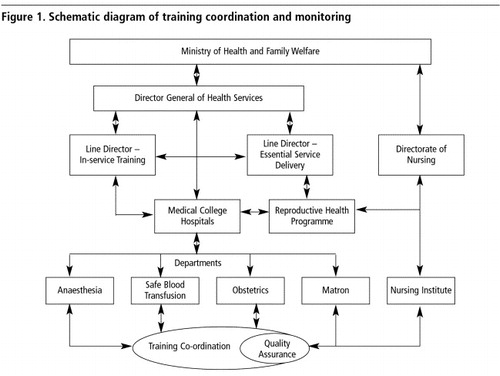

The implementation of the Health and Population Sector Programme (1998), the sector-wide approach adopted by the government to improve the overall health situation of the country, was a key factor in improving central level coordination and monitoring of training activities. At the national level, the Line Director for In-service Training of the Directorate General of Health Services coordinated all the training activities. The Training Coordination Committee at each medical college hospital reported to the Line Director. UNICEF maintained close connections with all levels of the Ministry and medical college hospitals in the implementation of the project. illustrates the connections between the different offices and departments involved.

Training activities were coordinated locally by the Training Coordination Committee at each medical college hospital. The committee was made up of representatives from the departments involved in the training programmes (obstetrics, anaesthesia, blood transfusion, nursing institute and the hospital matron), chaired by the director of the hospital. The committee designated a focal point for each department who was responsible for implementation, coordination and monitoring of training in their department. The committee provided an opportunity to increase the involvement of the heads of the training institutions, who had often been bypassed in the management plans of previous training activities. The committee also provided opportunities to improve training coordination by creating a forum to discuss progress and solve problems. Distribution of training funds and materials was decentralised and under control of the committee.

Trainees' performance was reviewed regularly by department heads, focal points and in Training Coordination Committee meetings. Trainees were also assessed through written and oral examinations at the middle and end of the course. Cumulative monthly performance reports were sent to the Line Director.

External monitoring by the senior teaching staff from fellow medical college hospitals was organised several times a year to review the quality of training. External monitoring visits across the training sites were found to be very effective in winning local support and co-operation to solve problems. Three visits per year were planned but two visits to each medical college hospital took place, with extra visits organised to handle specific problems.

The committees were supposed to meet once a month, but most did not meet regularly, due to lack of initiative, time constraints and lack of urgent agenda items. Meetings were called mainly if problems arose.

Post-training monitoring and follow-up visits were carried out by Quality Assurance Teams, a subset of the Training Coordination Committees. Guidelines and checklists were developed for this. Direct observation, review of recent cases and prepared case studies were among the tools used to focus on clinical skills. During the visit, the team assessed the performance of trainees in the preceding three months, and provided mentoring on site. Emergency preparedness of the facility was also reviewed.

The Quality Assurance Teams were supposed to conduct one follow-up visit per month to facilities in their area where trained staff were posted (mostly sub-district hospitals). The number of visits to a facility depended on staff performance. For those found to be performing well, only one or two quality assurance visits were needed; if performance was found to be poor, additional visits were arranged.

This responsibility posed its own challenges. Although there were some visits in 2002 and 2003, some of the medical college hospitals were unable to organise any visits. Further work is needed to institutionalise the quality assurance visits as a component of management and supervision, both at the training institution level and from the central level.

To facilitate implementation, coordination and monitoring activities, UNICEF assigned a Technical Officer (the first author) to the central level to provide technical support in planning, organising and implementing all the training activities, including curriculum development. He facilitated selection and placement of trainees, training monitoring, training facility needs assessment, post-training follow-up of performance, support to trainees at designated facilities (including logistics and minor equipment) and assessment of further training needs. He was also responsible for negotiation, advocacy, networking and coordination between the training institutions and departments, Programme Office, Line Directors and Director General of Health Services. The Technical Officer facilitated development of guidelines for the formation of Training Coordination Committees and Quality Assurance Teams, and monitored their activities. Moreover, the Technical Officer was responsible for the development of guidelines and facilitation of facility-level planning. In addition, there were 12 field officers assigned to monitor a group of facilities within their assigned area. The field officers provided some assistance to training activities, such as organisation of quality assurance visits, as well as following up with trained providers during routine site visits.

Achievements of the project

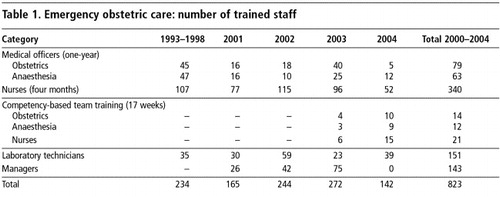

With improved planning and timely action, training activities were greatly accelerated under the project. During the previous project periods, an average of 15 medical officers (obstetrics and anaesthesia combined) completed the one-year training annually, compared to an average of 42 medical officers per year during the four years of the project (including competency-based training). For nurses, training numbers also improved from an average of 18 per year to 90, while training of laboratory technicians increased from 6 per year to 38. Table 1 shows the number of personnel trained in the different programmes.

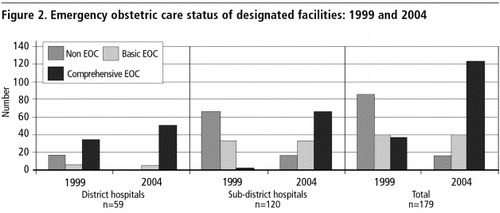

The training during this project has helped 105 of the 120 sub-district hospitals to become functional for EmOC – 70 comprehensive and 35 basic. This is compared to the 1999 baseline assessment where only three sub-district hospitals were providing comprehensive and 33 basic EmOC, mostly due to the lack of trained staff and necessary equipment.Citation9 Among the district hospitals, 53 out of 59 were providing comprehensive EmOC by the end of 2004, compared to only 35 in 1999 (). While the capacity for EmOC at district hospitals still relies mostly on the presence of consultants, trained nurses are nonetheless playing a central role in conducting normal deliveries, identifying complications and working with consultants to provide emergency services.

A change in status from non-functioning to functioning basic EmOC is only one step toward the project objectives but it signifies an improvement in capacity. An analysis of project records found that in facilities that reached basic EmOC status, most non-training inputs were completed but a trained medical officer was often missing, particularly for anaesthesia.

The low numbers of trainees entering and completing the various courses in 2004 can be attributed to several factors. For medical officers, the posts at the most desirable, easy-to-access facilities were already occupied, and there was less interest generated for postings to remote facilities. In the competency-based course, the key constraint was the number of seats per course. With only one training site offering the course, there were seats for 12–15 medical officers and nurses, or 3–4 teams. In addition, contract limits led to loss of project staff responsible for managing recruitment and implementation of training. Funding for the project also decreased in 2004; a cost extension made it possible to continue project activities past the original end date of mid-2004 but at a greatly reduced level.

Training costs

The direct costs, such as trainers' honorarium, trainees' travel and daily allowances, book grant, training materials, expenses related to facility set-up, monitoring and on-site mentoring were covered by the project. Per trainee costs were approximately US$1,550 for one year for medical officers, US$1,020 for 17-week competency-based training, US$340 for nurses and US$140 for laboratory technicians. Most of the cost of EmOC and training has to do with salaries and other costs borne by the government, such as salaries of trainers, medical officers, nurses, laboratory technicians and government project personnel, training facility infrastructure and related logistics. A more detailed analysis of costs is beyond the scope of this paper.

Discussion

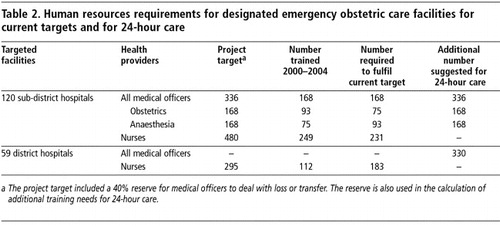

The human resources needs for this project were considerable. The large numbers of medical officers, nurses and laboratory technicians trained were an important part of the project's achievements. Nonetheless, there is still a long way to go to realise good quality, 24-hour EmOC in all designated facilities. In fact, if these facilities are ever to provide 24-hour care, seven days a week, more skilled providers will be required. The initial targets in this project were based on having two trained medical officers at each facility, working 40 hours a week, living on site and responding at any time to an emergency. This is not a realistic basis for 24-hour care, and does not address coverage when a doctor takes leave, is ill or is called to meetings. A more realistic target for 24-hour coverage would be at least four medical officers (two each for obstetrics and anaesthesia) at both sub-district and district hospitals (consultants at district hospitals also need back-up support for 24-hour care). This represents a three-fold increase over the current target for medical officers. A total of 834 medical officers will need to be trained to complete the current target as well as move toward 24-hour care. Four to five nurses with midwifery skills per facility, the target in this project, may be sufficient to provide 24-hour care by rotation, but by the end of 2004, the project had reached only 47% of its target (Table 2).

With current training capacity, it would take another 20 years, with an annual output of 40 medical officers, to obtain the desired number for 24-hour care, targeting mainly existing medical personnel through in-service training. However, if the 17-week competency-based training can be scaled up to additional training institutions, the time required could be greatly reduced. Retaining and motivating trainers and making training a key part of their duties are important if this course is to be expanded and sustained, along with sufficient funds to support direct training costs. There is a government mechanism to cover the travel and daily allowances for staff, but the amount is insufficient to encourage staff to attend training and organise monitoring and on-site quality assurance visits. Other factors include attracting more medical officers for training, and retention of medical officers in rural facilities. Recognition of work in hardship posts could be factored into benefits packages, professional advancement and other incentives for attracting and retaining medical officers in designated facilities.

There are generally sufficient numbers of medical officers working in the public system to meet the above targets, but the distribution of medical officers between urban and rural facilities, and retaining them at rural posts, requires further improvement. Given the national scope of the project, requiring in-service training in skills for EmOC for medical officers would be a stronger course of action than soliciting interest in training. Delegation of a wider range of procedures to trained nurses, such as manual removal of placenta, removal of retained products and management of postpartum haemorrhage, would help to redistribute the caseload within facilities and could prevent maternal deaths where trained medical officers were not available.

In the long term, the skills covered during in-service training need to be incorporated into pre-service training, e.g. the internship of new medical graduates. As general medical officers and nurses are the main health care providers in rural facilities, particularly sub-district hospitals, emergency obstetric skills should become an essential part of their basic training. This will require strong advocacy for change among professors and policymakers.

The need for evidence-based protocols to standardise practice emerged during this project, and the protocols developed during the project are currently under review by the government. There is certainly room for care to be improved in medical college hospitals, as well as district and sub-district hospitals. Clinical standards are an important tool in assessing clinical skills, as well as quality of care. The modelling of good quality care is crucial during training so that these practices are continued in rural facilities. This was another reason for the introduction of competency-based training. The integration of evidence-based practices to improve the quality of routine care requires ongoing advocacy among professors, trainers and senior doctors.

The involvement of key stakeholders, particularly the directors of the medical college hospitals, helped to promote understanding of EmOC training activities and needs, as well as systems of accountability. Training departments and focal points were held accountable to the Training Coordination Committee, while the committee was accountable to the Line Director. Although this system involved some administrative complexities, the improvements in training management could prove beneficial.

This project helped to improve the availability of EmOC services in Bangladesh as well as the training management system. Training of all categories of service providers was found to be satisfactory. The commitment of senior management was essential to coordination and monitoring. Finally, the project assisted the Government in realising elements of the Health, Nutrition and Population Sector Programme goals.

Nevertheless, more trained EmOC providers are needed to reduce the high burden of maternal mortality in Bangladesh and to achieve the desired level of availability of EmOC. In fact, an additional 12 sub-district hospitals were added to the list of designated facilities in 2005. Training courses were conducted in 2005, and initiative was taken to expand competency-based training to three additional training facilities. UNICEF has continued to support project activities through regular funding sources and has been working with the Government of Bangladesh to generate continued commitment to sustain the project. There are clear advantages to the competency-based training course but continued implementation of this and other human resources development initiatives will require greater commitment and support from trainers and training departments, policymakers and managers, as well as from development partners.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the support of the Averting Maternal Death and Disability Programme (AMDD), Columbia University, and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, and the technical support of UNICEF's Regional Office for South Asia, JHPIEGO and AMDD. We are grateful to Dr Dileep Mavalankar, Management Advisor for AMDD and Associate Professor, Indian Institute of Management, Ahmedabad, for his continuous encouragement in writing this paper. Our sincere thanks to Dr Iftekhar Hossain for valuable comments and suggestions, which have greatly enriched the paper.

Notes

1 Emergency obstetric care includes: administration of parenteral antibiotics, oxytocics and anticonvulsants; manual removal of placenta; removal of retained products; assisted vaginal delivery; caesarean section; and blood transfusion. Basic emergency obstetric care provides the first six functions. Comprehensive emergency obstetric care provides all eight functions. A facility is considered non-functional if it does not provide all the functions to qualify as either basic or comprehensive, even if the facility is performing many of these functions.Citation12 Designated facilities refer to the facilities selected by the government to provide comprehensive EmOC and were the target of project interventions (59 district hospitals and 120 sub-district hospitals). Others are defined as non-designated facilities.

2 There is an extensive private sector in Bangladesh with some capacity to treat obstetric emergencies,Citation9 but the focus here is on public sector facilities.

References

- National Institute of Population Research and Training, ORC Macro. Bangladesh maternal health services and maternal mortality survey 2001. 2002; NIPORT: Dhaka.

- United Nations Children's Fund. The State of the World's Children 2001. 2001; UNICEF: New York.

- UNICEF WHO UNFPA. Maternal Mortality in 2000: estimates developed by WHO, UNICEF and UNFPA. 2004; World Health Organization: Geneva.

- YA Haque, G Mostafa. A review of the emergency obstetric care functions of selected facilities in Bangladesh. 1993; UNICEF: Dhaka.

- D Maine. Safe Motherhood Programmes: Options and Issues. 1993; Centre for Population and Family Health, School of Public Health, Columbia University: New York.

- Directorate General of Health Services, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. Project Report: Pilot Project for Maternal and Neonatal Health Care. 1998; Directorate General of Health Services: Dhaka.

- Z Gill, JU Ahmed. Experience from Bangladesh: implementing emergency obstetric care as part of the reproductive health agenda. International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics. 85: 2004; 213–220.

- Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics. Official Statistics: Data Sheet-1999. Dhaka: Ministry of Planning. At: <www.bbsgov.org. >. Accessed 9 January 2006.

- MSH Khan, ST Khanam, S Nahar. Review of availability and use of emergency obstetric care services in Bangladesh. October. 2001; Associates for Community and Population Research: Dhaka.

- MT Islam, M Hossain, MA Islam. Improvement of coverage and utilisation of EmOC services in South-Western Bangladesh. International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics. 91(3): 2005; 298–305.

- UNICEF. Women's Right to Life and Health: Accelerating Efforts to Reduce Maternal Deaths and Disability in Bangladesh. A collaborative initiative of the Government of Bangladesh, UNICEF and Columbia University. 2000; UNICEF: Dhaka.

- UNICEF WHO UNFPA. Guidelines for monitoring the availability and use of obstetric services. 1997; UNICEF: New York.

- Research Evaluation Associates for Development (READ). Report on post-training evaluation of medical officers, nurses and lab technicians on emergency obstetric care. 2004; READ: Dhaka.

- Sanghvi H. Training district emergency obstetric care teams: strategy for maximising investment in training. Competency-based training strategy paper. Baltimore, 2001.

- JHPIEGO AMDD. Emergency Obstetric Care for Doctors and Midwives: Course notebook for trainers and participants. June. 2003. At: <http://www.reproline.jhu.edu/english/2mnh/2obs_care/EmOC/index.htm. >. Accessed 11 January 2006.

- JHPIEGO AMDD. Anaesthesia for emergency obstetric care. June. 2003. At: <http://www.reproline.jhu.edu/english/2mnh/2obs_care/AEmOC/index.htm. >. Accessed 11 January 2006.

- WHO UNFPA UNICEF World Bank. Managing Complications in Pregnancy and Childbirth: A Guide for Midwives and Doctors. 2003; WHO: Geneva.