Abstract

Japan has been experiencing a continuing decline in fertility and an increase in premarital conceptions and abortions among young people. Child rearing is often viewed as a burden. In response, Japan is now seeking ways to improve the child-rearing environment for parents. In this context, we conducted a prospective study among 206 pregnant women in Sukagawa City, Fukushima, to explore the influences of pregnancy intention on child rearing. We found that unintended pregnancy was associated with a higher risk of negative child-rearing outcomes, including lower mother-to-child attachment, increased negative feelings of mothers and a lower level of participation of fathers in child rearing. Unintended pregnancy exacerbates the real and perceived burdens of child rearing. Japan is currently facing a conflict between wanting to reduce unintended pregnancies and increase the national fertility rate. We believe the government needs to address the social challenges affecting people's family lives, which underpin low fertility, rather than focus on fertility decline per se. We suggest Japan seeks to reduce unintended pregnancies and provide support to parents at high risk of child-rearing difficulties. We also suggest adopting a comprehensive approach to improving the lives of young couples, with a focus on adolescents, including life-skills education to prepare for adulthood, marriage and parenthood.

Résumé

Le Japon a enregistré une baisse suivie de la fécondité et une augmentation des conceptions prémaritales et des avortements chez les jeunes. L'éducation des enfants est souvent considérée comme un fardeau. Par conséquent, le Japon cherche maintenant à améliorer les conditions dans lesquelles les parents élèvent leurs enfants. Dans ce contexte, nous avons réalisé une étude prospective auprès de 206 femmes enceintes à Sukagawa, Fukushima, pour analyser les influences de l'intention de grossesse sur l'éducation des enfants. Une grossesse non désirée était associée avec un risque supérieur de conséquences négatives sur l'éducation de l'enfant, avec notamment un lien moins étroit entre la mère et l'enfant, des sentiments négatifs accrus chez les mères et moins de participation des pères à l'éducation de l'enfant. Une grossesse non désirée exacerbe les fardeaux réels et perçus du rôle de parent. Le Japon connaît actuellement un conflit entre la volonté de réduire les grossesses non désirées et celle d'accroître le taux national de fécondité. Nous pensons que le Gouvernement doit aborder les problèmes sociaux touchant la vie familiale, qui motivent la faible fécondité, plutôt que de se centrer sur la baisse de la fécondité en tant que telle. Il doit s'efforcer de réduire les grossesses non désirées et soutenir les parents à haut risque de difficultés dans l'éducation des enfants. Nous préconisons également une approche globale pour améliorer la vie des jeunes couples, axée sur les adolescents, avec une éducation aux compétences essentielles pour les préparer à l'âge adulte, au mariage et au rôle de parents.

Resumen

En Japón, la juventud ha experimentado un descenso continuo en fertilidad y un aumento en concepciones y abortos premaritales. A menudo se percibe la crianza de los hijos como una carga. Por ello, se están investigando formas de ayudar a los padres al respecto. En este contexto, se realizó un estudio prospectivo entre 206 mujeres embarazadas en Ciudad de Sukagawa, Fukushima, a fin de explorar las influencias de la intención relacionada con el embarazo en la crianza de los hijos. Se encontró que el embarazo no intencional estaba asociado con mayor riesgo de resultados negativos: por ejemplo, menos apego de madre a hijo, aumento en los sentimientos negativos de las madres y menos participación de los padres en la crianza de los hijos. El embarazo no intencional exacerba las cargas reales y percibidas de la crianza de los hijos. Actualmente, Japón afronta un conflicto entre su deseo de disminuir la tasa de embarazos no intencionales y aumentar la tasa nacional de fertilidad. Estimamos que el gobierno necesita abordar los retos sociales que afectan la vida en familia, los cuales sustentan una baja tasa de fertilidad, y no centrarse en el descenso de la fertilidad en sí. Sugerimos que Japón se proponga disminuir la tasa de embarazos no intencionales y brindar apoyo a los padres que corren alto riesgo de tener dificultades con la crianza de los hijos, así como adoptar una estrategia integral para mejorar la vida de las parejas adolescentes, que incluya preparación para la adultez, el matrimonio y la paternidad/maternidad.

The arrival of a new baby brings both happiness and challenges to any family. In Japan, however, the challenges often seem to surpass the happiness. For several decades, Japan's total fertility rate has continued to decline, from around 2.1 in the second baby boom period between 1971 and 1974 to 1.29 in 2004 ().Citation1 The increase in total population has slowed since 1975 (annual increase rate: 1.5% in 1975, 0.2% in 2000), and the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare recently reported that the population had fallen for the first time by approximately 44,000 people in 2005. According to the 12th National Fertility Survey in 2002, the proportion of married couples with fewer children than they desired was 37%, and the top three reasons were financial burdens, unfavourable social attitudes toward raising children, and the mental and physical burdens of child rearing.Citation2]

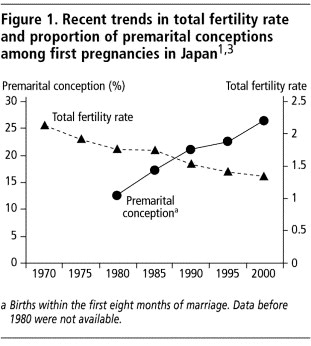

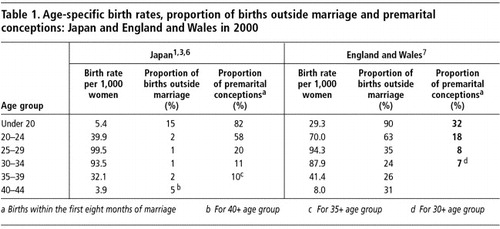

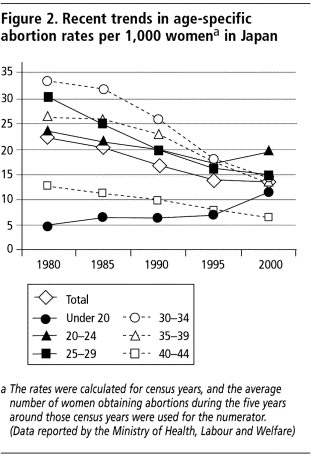

While Japan's fertility rate has declined, the proportion of premarital conceptions among first births (births within the first eight months of marriage) has increased sharply from 13% in 1980 to 26% in 2000 ().Citation3 The number in 2000 was particularly high among those aged 15–19 and 20–24 years, 82% and 58%, respectively. The proportion of premarital conceptions among first births is probably the best available national indicator of unintended pregnancy in Japan. While not all premarital conceptions are unintended, our previous study in one prefecture in Japan showed that 97% of first pregnancies among single women were described as unintended, compared to only 10% for married women.Citation4 Unintended pregnancies are also reflected in Japan's abortion statistics, which show a marked increase in the abortion rate among young women under 25 years old ().Citation5 Although people are tending to postpone marriage and childbearing, they are also becoming sexually active at an earlier age, often without using effective contraception. Unintended pregnancy among unmarried couples thus is more likely than before. With low social acceptability of childbearing outside marriage in Japan, couples with a premarital conception are likely to marry if they decide to have the baby. A comparison with England and Wales, where comparable data are available, highlights the unique features of Japanese fertility patterns among younger age groups (Table 1).Citation1Citation3Citation6Citation7 These include a low birth rate, uncommon births outside marriage and frequent premarital conceptions. While over 60% of births outside marriage occur in cohabiting couples in England and Wales,Citation7 the situation is markedly different in Japan, where cohabitation is uncommon.Footnote1 This makes the figures on premarital conception all the more surprising in Japan.

Since data on unintended pregnancy are scarce in Japan, we conducted two cross-sectional studies on the topic. The first study targeted 564 women in the late reproductive period and investigated frequency and factors associated with unintended pregnancy.Citation4 The second study was conducted in preparation for the present study and used data from one city's health survey among mothers of 317 randomly selected children aged 3–18 months.Citation9 The survey provided preliminary results on the proportion of unintended pregnancies among births and the association between pregnancy intention and child-rearing outcomes. These two studies found that nearly half of Japanese women aged 35–49 years had experienced unintended pregnancies (including those that ended in abortion),Citation4 and that 20% of first births were the outcome of unintended pregnancy.Citation9 By contrast, in the Netherlands, which has one of the lowest rates of unintended pregnancy in Europe, the proportion of unintended pregnancies among first births is reported to be 6%.Citation10 When unintended pregnancy is carried to term, studies in Europe and North America have shown that pregnancy intention influences the child's physical and mental health.Citation11Citation12 However, very little is known about these processes in Japan. Our second study indicated possible associations between pregnancy intention and child-rearing outcomes, but the retrospective nature of the survey made it prone to recall bias.Citation9

According to official Japanese statistics, the number of child abuse cases reported to child consultation centres across the nation rose sharply from 1,101 in fiscal 1990 to 17,725 in 2000,Citation13 due in part to improved reporting after the Child Abuse Prevention Law was enacted in 2000. The number of reported cases has continued to increase since then and reached over 32,000 in 2004. Parents of these reported cases are characterised by poverty, personality problems, parental conflict and complicated family relations, followed by societal isolation, their own childhood family problems and unintended pregnancy.Citation14Citation15 Increased social attention to parent–child relationships has also resulted from a rising number of cases of social withdrawal among young people and crimes carried out by minors.Citation16 In response, the Japanese government set as one of its four major objectives for the “21st Century Healthy and Happy Family”Citation17 to promote the healthy psychological development of children and alleviate parents' anxiety in relation to child rearing.

We conducted this small-scale, prospective, exploratory study, the first of its kind in Japan, to explore the potential influences of unintended pregnancy on child-rearing outcomes and to discern what possible actions could improve the child-rearing environment in Japan. The study focused on the earliest stages of parenting, since it has been reported that about one-third of child abuse cases were detected and began receiving attention from public health nurses during pregnancy or infancy,Citation18 and nearly 40% of fatal cases occurred during infancy, especially among children under two months old.Citation19

Methods

For this study, we targeted all the women (222) who registered their pregnancy in Sukagawa City, Fukushima, from November 2003 to March 2004. In 2003, the city had a population of 67,673 and reported 648 live births. The reported abortion rate in Fukushima was 15.8 per 1,000 women in 2004, and the estimated number of abortions in Sukagawa City during the survey period was 80, based on the prefectural abortion rate and the city's population data. Pregnant women in Japan are required to report their pregnancies to a city office and receive a Mother and Child Health Handbook, which is for recording the results of antenatal care visits and child growth. Unlike most municipalities, where a city officer simply gives the handbook to a woman, in Sukagawa City a public health nurse provides health counselling along with the handbook. We used these sessions as an opportunity to collect baseline information. The follow-up survey questionnaires were mailed approximately six weeks after the women's expected delivery date, i.e. April to November 2004. A reminder was sent if a woman did not return the questionnaire within two weeks. The median number of days after delivery for responding to the follow-up survey was 56. The study was approved by the ethics committee of the Fukushima Medical University. The study was explained to all the women, and oral consent was obtained from all participants.

The city's health counselling sheet provided the following baseline information: age and work of the woman and her husband, reproductive history, family living together, smoking and drinking habits, pregnancy intention, and health status. A question on pregnancy intention was designed based on the definition used in the National Survey of Family Growth, developed in the United States,Citation20 whose reliability and validity had been confirmed in our previous studies.Citation9Citation21 We asked the women how they felt at the time they realised they were pregnant. Four responses were offered: “The pregnancy was at the right time”; “The pregnancy was too soon”; “I wanted a child, but the pregnancy was too late”; and “I did not want to have a child or any more children, even in the future”. The first and the third responses were classified as intended and the second and the fourth as unintended.

For the follow-up survey, we employed the Maternal Attachment Inventory–Japanese Version (MAI) to assess the mother's attachment to her baby.Citation22 This eight-item inventory asks the woman to rate each statement regarding her feelings toward her baby using a four-point Likert scale from “not at all” (one point) to “very much” (four points). A higher score indicated greater attachment.

Five questions from the National Child Health Survey were used to assess the mother's subjective feelings towards child rearing, her evaluation of her own and the father's participation in child rearing, and her help-seeking behaviour.Citation23 These same five questions were also adopted as indicators in the government's plan for the 21st Century Healthy and Happy Family: Citation17]

| • | Are there any moments when you don't feel confident about child rearing? | ||||

| • | Are there any moments that you feel you are abusing your child? | ||||

| • | Do you feel that you can spend time in a relaxed mood with your child? | ||||

| • | Do you discuss child rearing with your husband, family, or friends? | ||||

| • | Do you think the child's father is cooperative in child rearing? | ||||

The data obtained were analysed using statistical software STATA version 8 for Windows (Stata Corporation, College Station, TX). First, the extent to which unintended pregnancies were associated with a higher risk of negative child rearing was examined, using multiple logistic regression analysis, while controlling for the following factors reported to relate to child-rearing difficulties in Japan: mother's age and occupation, whether she was a first-time mother or not, father's occupation, child's birth weight and co-habitation with grandparents.Citation9 All outcome indicators were categorised into dichotomies. As for the Maternal Attachment Inventory score, the lower third (less than 29) were categorised as the lower attachment group. The sum of significant negative child-rearing outcomes was also calculated, and the scores for the unintended and intended pregnancy groups were compared.

Results

Of the 222 women, 12 refused to participate in the survey and four were not enrolled due to lack of information on pregnancy intention. Baseline data were thus obtained from 206 women, of whom 140 were followed until the sixth week post-partum (follow-up rate=68%).

The number of unintended births was 42 out of 206 (20%) among the respondents to the baseline survey. The unintended and intended pregnancy groups differed significantly in the following characteristics (p<0.05, Chi-square test or Fisher's exact test for categorical items and Wilcoxon rank sum test for discrete items):

| • | age of mother – median 26 years old for unintended pregnancy vs. median 28 years old for intended pregnancy, | ||||

| • | age of father – median 28 years old vs. median 31 years old, | ||||

| • | proportion of mothers under 20 years old – 24% vs. 2% | ||||

| • | proportion of mothers who were singleFootnote2 – 33% vs. 11% | ||||

| • | had previous abortion – 21% vs. 7% | ||||

| • | smoked before pregnancy – 52% vs. 29%, and at the time of survey – 29% vs. 9%; and | ||||

| • | number of weeks pregnant at the time of pregnancy registration – 12 weeks vs. 10 weeks. | ||||

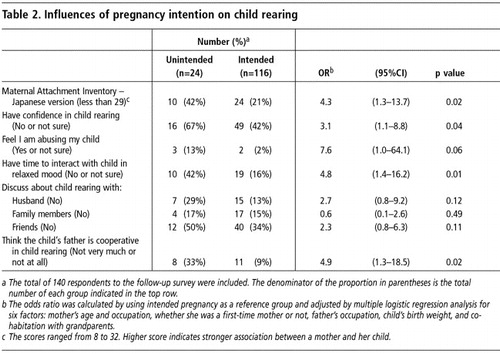

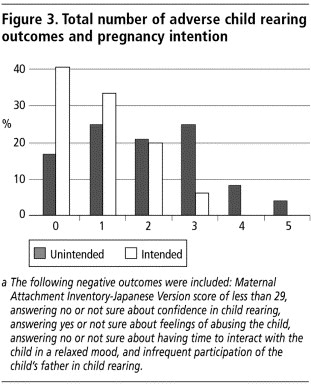

As shown in Table 2, unintended pregnancy increased the risk of lower mother-child attachment (MAI less than 29) (OR=4.3), answering no or not sure about confidence in child rearing (OR=3.1), yes or not sure about feeling toward child abuse (OR=7.6), no or not sure about having time to interact with the child in a relaxed mood (OR=4.8), and father's limited participation in child rearing (OR=4.9). shows that the total number of the above five negative child-rearing consequences was higher in the unintended pregnancy group than the intended pregnancy group [unintended pregnancy: median 2 (range 0–5); intended pregnancy median 1 (range 0–3)].

The data analysis suggests that unintended pregnancy has a higher risk of leading to negative child-rearing outcomes. Although further investigation is needed to confirm these results and to explore potential longer-term effects, the results are remarkable since unintended pregnancies taken to term are presumably less intensely unwelcome than those that are terminated (given that abortion is legal and common in Japan). In Sukagawa City, the pregnancy intention status of each registered pregnancy has been recorded since the start of this study. The database is expected to provide useful epidemiological data in future on unintended pregnancies in Japan.

Study limitations

The sample size was small and 32% of the women in the baseline survey were lost to follow-up. An analysis of differences in characteristics between respondents and non-respondents to the follow-up survey showed that median age for non-respondents at the time of the survey was younger (respondents 29 vs. non-respondents 27) and age at marriage lower (25 vs. 23), while the proportion of unemployed (37%, 53%), smokers (26%, 50%) and everyday drinkers (2%, 10%) was higher, with statistical significance. Although not statistically significant, the proportion of unintended pregnancies was higher in the non-respondents group (17% vs. 27%). Respondents of health surveys are known to have healthier life styles compared to non-respondents,Citation24 and one should be cautious in interpreting the results of the present survey, since it may under-estimate the association of pregnancy intention with child-rearing outcomes. Despite the small sample size and the potential selection bias which may have left relatively healthier women in the follow-up survey, however, we were able to observe significant influences of pregnancy intention on child rearing.

Supporting parenthood

Preventing unintended pregnancies

Our past and present research and the analysis of national statistics for Japan have shown that unintended pregnancy is not a rare event. Further, this prospective study identifies some effects of unintended pregnancy on child rearing. We suggest that efforts to improve the child-rearing environment in Japan should start with a primary prevention approach, aiming to increase knowledge and understanding of young women and men about using contraception, in order to reduce the number of unintended pregnancies.

As described in earlier research on abortion trends and the process of the approval of oral contraceptives in Japan,Citation5Citation25 efforts are needed to enable women and men to take more responsibility for controlling their own fertility and increase their access to effective modern contraceptives. Despite the approval of oral contraceptives in Japan in 1999, a survey conducted in 2004 found that condoms remained the contraceptive of choice for 68% of married women aged 16–49 years practicing contraception, followed by withdrawal (17%) and rhythm methods (7%).Citation26 The proportion of oral contraceptive users was as low as 1.5% in the same survey. Other nationwide surveys in Japan have reported that 85% of pharmacies did not usually stock oral contraceptivesCitation27 and 75% of family physicians offered no contraceptive services in practice.Citation28

Supporting couples with unintended pregnancies

The second approach we recommend is a more systematic identification of couples with unintended pregnancy and other high risk cases of child-rearing difficulties at pregnancy registration, in order to allow early initiation of support during pregnancy and post-partum to help couples accept their parental roles and improve their parenting skills. Currently, Japan offers various social resources to support couples with children. Local health centres, for example, organise parenting classes for pregnant women and their partners, child-rearing classes for mothers, and home-visit programmes by public health nurses. In addition, there are self-help community circles for mothers. However, only a small proportion of mothers participate in these programmes and activities; 15% in Sukagawa City, according to the city's 2002 data. As for the home-visit programmes, some municipalities target all mothers with newborn babies, but others visit only selected “high-risk” cases, often without a clear definition or screening system. With support from Sukagawa City, we are in the process of developing a systematic screening system for high-risk cases of child-rearing difficulties and a parenting support programme for these couples.

Further implications for policy on fertility decline and child rearing

Current child-rearing environment and policies in Japan

In Japan, child rearing is often viewed as a financial, physical and psychological burden. As more Japanese women enter the workforce, having a baby is commonly considered an obstacle. This “burden” is increased by an unintended pregnancy that makes it difficult for a couple to plan their family life. Problems in parenting following an unintended pregnancy, which are suggested by our study results, may exacerbate the real and perceived burdens of child rearing and hinder the capacity of parents to create a positive child-rearing environment.

Social policies to improve the child-rearing environment and encourage young couples to enter parenthood in a positive way are a challenge not only for Japan but also other countries experiencing fertility decline. Japan is now showing striking similarities to the lowest low-fertility countries in Southern Europe (Italy and Spain in particular). These features include infrequent births outside marriage, limited use of effective contraceptive methods, increased premarital conception, more women entering the workforce, limited participation of men in child rearing and housework, mothers' low self-evaluation of competency in parenting, and more younger people without stable work and living in their parents' home for longer periods of time, in addition to a general delay in the age of marriage and childbearing.Citation29Citation30Citation31 In these countries, traditional views on family and gender roles, along with delayed efforts to improve the work environment and childcare services, are creating social and individual conflicts in balancing employment and family and discouraging women from entering motherhood.Citation30

Younger people's limited independence from their parents is further delaying their own family formation.Citation30 According to a Japanese government report, an estimated 640,000 people aged 15–34 years in 2004 were not keeping house, attending school or working in the labour force – known in Japan as NEET (Not in Education, Employment or Training). Japan's difficult employment situation is an important reason for young people becoming NEET, but the most common reason given by those who are unemployed and have never engaged in job-seeking activities is a lack of confidence in “getting along with people and other aspects of life in society”.Citation32 These data suggest that the issue of low fertility is deeply rooted in a complex interaction of traditional family values, inadequate social structures and young people's lack of autonomy.

Japan has introduced various schemes to address its fertility decline since 1990. The “New Angel Plan”, a national plan to promote childcare support, was announced in 2000 and evaluated in 2004. The plan's major shortcoming was that its aim was limited to improving childcare facilities. Moreover, the evaluation indicators measured the provision of services, but not their impacts. As a result, the evaluation concluded that the psychological and financial burdens of child rearing had not declined while the total fertility rate had kept decreasing. In response, a new law for promoting measures to support childcare was enacted in July 2003, and in 2004 the government developed a Child and Child Rearing Support Plan. It recommends both structural and value changes aimed at encouraging higher fertility, with the objectives of promoting autonomy among youths, improving the balance between work and family, providing education on the importance of life and family among youths, and strengthening social networks to support child rearing. Specific strategies for each objective include the promotion of employment among young people, parental leave for both women and men and shortening work hours, education for adolescents to learn child rearing, and setting up networking centres to support childcare.

Promoting life planning among adolescents

We suggest that Japan adopt a more comprehensive approach to improving the lives of young couples, with a focus on adolescents, which is a critical period of development, to address the frequent premarital conceptions and increasing abortion rate among adolescents and young adults.

It is unlikely that Japan's current practices of child-rearing education for adolescents (school and community programmes that provide opportunities for young people to interact with babies and little children) will help young women and men to discuss their family life plans, including pregnancy and childbirth. On the other hand, experience in other countries has shown that life-skills education can help young people develop critical capacities that adolescents need (assertiveness as well as communication and decision-making skills),Citation33Citation34 and is effective in reducing unprotected sex and substance abuse.Citation35Citation36 Interestingly, our study found that women with unintended pregnancy were more likely to smoke and drink than those with intended pregnancy. Life-skills education uses a participatory approach that facilitates learning without dictating a specific course of action.Citation37 The development of a life-skills education programme adapted to the Japanese cultural context could have a positive impact on the capacity of young people in Japan to prepare for adulthood, marriage and parenthood.

Conclusions

Japan is currently facing a conflict (with important political implications) between the need to reduce unintended pregnancies and the desire to increase the national fertility rate. A similar conflict contributed to the long-delayed approval of oral contraceptives in Japan, as the government worried about shoshika mondai (the problem of fewer children).Citation25 We believe that the Japanese government and society need to deal with this dilemma by addressing the social challenges affecting people's family lives which underpin low fertility, rather than focus on the decline in population per se. It is doubtful that there is a single solution for these complex problems, as they are affecting more countries than Japan alone.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported in part by Tokubetu Kenkyu Shorei Hi (Research Promotion Grant) of Fukushima Medical University and a Grant-in-Aid for Young Scientists (B) of the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science. We thank Michiko Yomogida for her assistance with data management and appreciate the thoughtful comments of Susan Pick on an earlier version of this paper.

Notes

1 In Japan, the proportion of singles aged 18–50 who were cohabiting was 2% in 2002, compared to 25% in England and 27% in Wales among singles aged 16–59 in 2000–02.Citation2Citation8

2 “Single” in this paper means “not legally married”. In the baseline survey, there were 17 single, pregnant women, of whom six lived with their partners.

References

- Trends in the Nation's Health. 2004; Health and Welfare Statistics Association: Tokyo. [In Japanese].

- Institute of Population Problems. 12th Basic Survey on Birth (Marriage and Fertility). 2004; Health and Welfare Statistics Association: Tokyo. [In Japanese].

- Statistics and Information Department, Minister's Secretariat, Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. Summary Report on Birth Statistics. [In Japanese] At: <http://www.mhlw.go.jp/toukei/saikin/hw/jinkou/tokusyu/syussyo-4/>. Accessed 7 July 2005.

- A Goto, S Yasumura, MR Reich. Factors associated with unintended pregnancy in Yamagata, Japan. Social Science and Medicine. 54: 2002; 1065–1079.

- A Goto, C Fujiyama-Koriyama, A Fukao. Abortion trends in Japan, 1975–95. Studies in Family Planning. 31: 2000; 301–308.

- Statistics and Information Department, Minister's Secretariat, Ministry of Health and Welfare. Vital Statistics of Japan 2000. Tokyo, 2002. [In Japanese]

- Office for National Statistics. Birth Statistics, Review of the Registrar General on Births and Patterns of Family Building in England and Wales, 2003. London, 2004.

- National Statistics. 3.18 Cohabitation amongst non-married people aged 16 to 59, 2000-021. At: <http://www.statistics.gov.uk/STATBASE/Expodata/Spreadsheets/D7677.xls>. Accessed 2 February 2006.

- A Goto, S Yasumura, J Yabe. Association of pregnancy intention with parenting difficulty in Fukushima, Japan. Journal of Epidemiology. 15: 2005; 244–246.

- S Delbanco, J Lundy, T Hoff. Public knowledge and perceptions about unplanned pregnancy and contraception in three countries. Family Planning Perspectives. 29: 1997; 70–75.

- SS Brown, L Eisenberg. The best intentions: unintended pregnancy and the well-being of children and families. 1995; National Academy Press: Washington DC.

- HP David. Born unwanted, 35 years later: the Prague study. Reproductive Health Matters. 14(27): 2006; 181–190.

- Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, Equal Employment, Children and Families Bureau. Statistics of the child maltreatment cases reported to child consultation centres. 2000. At: <http://www.mhlw.go.jp/houdou/0106/h0621-4.html. >. Accessed 7 July 2005. [In Japanese].

- Sato T. Child Abuse Prevention Manual for Public Health Nurses. At: <http://rhino.yamanashi-med.ac.jp/sukoyaka/pdf/gyakum.pdf>. Accessed 15 November 2005. [In Japanese]

- M Tanimura, I Matsui. Risk factors of child abuse. Hoken no Kagaku. 41: 1999; 577–582.

- J Watts. Public health experts concerned about hikikomori. Lancet. 359: 2002; 1131.

- Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. The 21st Century Sukoyaka (Healthy and Happy) Family Working Group. The 21st Century Sukoyaka (Healthy and Happy) Family Report. Tokyo, 2000. [In Japanese]

- K Yamada, J Noda. A study on child abuse and neglect cared by public health nurse (PHN) of local health center: Based on nationwide survey. Shoni Hoken Kenkyu. 61: 2002. 568–67.

- A Sagami, N Kobayashi, M Tanimura. Child abuse fatalities in Japan from a nationwide survey of child abuse and neglect 2000. Child Abuse and Neglect. 5: 2003; 141–150. [In Japanese].

- JC Abma, A Chandra, WD Mosher. Fertility, family planning, and women's health: new data from the 1995 National Survey of Family Growth. Vital and Health Statistics Series 23, No.19. 1997; Center for Disease Control and Prevention: Hyattsville.

- A Goto, S Yasumura, A Fukao. A reproductive health survey on unintended pregnancy in Yamagata, Japan: feasibility of the survey and test-retest reliability and validity of a questionnaire. Journal of Epidemiology. 10: 2000; 376–382.

- T Nakajima. Reliability and validity of the maternal attachment questionnaire. Shoni Hoken Kenkyu. 61: 2002; 656–660.

- Nihon Shoni Hoken Kyokai. Child Health Survey 2000. 2001; Tokei Insatsu: Tokyo. [In Japanese].

- S Nakai, S Hashimoto, Y Murakami. Response rates and non-response bias in a health-related mailed survey. Nippon Koshu Eisei Zasshi. 44: 1997; 184–191.

- A Goto, MR Reich, I Aitken. Oral contraceptives and women's health in Japan. Journal of the American Medical Association. 282: 1999; 2173–2177.

- The second survey on lives and attitudes of women and men: reproductive health knowledge, attitudes and practices. 2005; Japan Family Planning Association: Tokyo. [In Japanese].

- K Matsumoto, Y Ohkawa, K Sasauchi. A survey on low-dose oral contraceptive transactions at pharmacies. Yakugaku Zasshi. 123: 2003; 157–162.

- K Kitamura, MD Fetters, N Ban. Contraceptive care by family physicians and general practitioners in Japan: attitudes and practices. Family Medicine. 36: 2004; 279–283.

- MH Bornstein, OM Haynes, H Azuma. A cross-national study of self-evaluations and attributions in parenting: Argentina, Belgium, France, Israel, Italy, Japan, and the United States. Developmental Psychology. 34: 1998; 662–676.

- H Nishioka. Low fertility and demographic, socio-economic changes in Southern European Countries. Journal of Population Problems. 59(2): 2003; 20–50.

- TC Martin. Delayed childbearing in contemporary Spain: trends and differentials. European Journal of Population. 8: 1992; 217–246.

- Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. White Paper on the Labour Economy 2005. 2005; Gyosei: Tokyo. [In Japanese].

- O Bayley. Improvement of sexual and reproductive health requires focusing on adolescents. Lancet. 362: 2003; 830–831.

- World Health Organization. WHO life-Skills Education Programme. 1997; Taishukan Shoten: Tokyo. [In Japanese].

- S Pick, M Givaudan, YH Poortinga. Sexuality and life skills education. A multistrategy intervention in Mexico. American Psychologist. 58: 2003; 230–234.

- GJ Botvin, LW Kantor. Preventing alcohol and tobacco use through life skills training. Alcohol Research and Health. 24: 2000; 250–257.

- World Health Organization. Information series on school health. Document 9. Skills for Health. 2003; World Health Organization: Geneva.