Abstract

This article describes a programme to scale up post-abortion care services in 22 of the 33 public sector district hospitals in Guatemala from July 2003 to December 2004. The main interventions included strengthening the knowledge and technical capacity of staff, expanding post-abortion care, enhancing related infrastructure, distributing informational materials andinstituting an abortion surveillance system. A facilitator supported the work through week-long, monthly visits at each hospital. Attention was also devoted to building institutional consensus in support of post-abortion care at government, district hospital and hospital staff levels. Duringthis period, 13,928 women with incomplete abortions were admitted to the 22 hospitals. Use of manual vacuum aspiration for treatment of incomplete first trimester abortion increased from 38% to 68% of cases (p<0.0001). Provision of family planning counselling also increased, from 31% to 78% of women (p<0.0001), and the proportion of women selecting a contraceptivemethod before leaving hospital from 20% to 49% (p<0.0001). Infection was associated with 71% of the incomplete abortions, of which 90% were septic. There were nine deaths and 768 women suffered severe complications, the level of which remained unchanged during the study period. Guatemala still has much to do to institutionalise post-abortion care fully and reduce deaths and complications, but our efforts to date will be valuable to others.

Résumé

L'article décrit un programme d'élargissement des services de soins post-avortement dans 22 des 33 hôpitaux publics de district au Guatemala de juillet 2003 à décembre 2004. Les principales interventions visaient à renforcer les connaissances et les compétences techniques du personnel, agrandir les installations de soins post-avortement, améliorer les infrastructures de base liées, distribuer du matériel informatif et instaurer un système de surveillance des avortements. Un facilitateur a soutenu le travail pendant des visites mensuelles d'une semaine dans chaque hôpital. Une attention a aussi été accordée à l'établissement d'un consensus institutionnel à l'appui des soins post-avortement aux niveaux de l'État, des hôpitaux de district et du personnel hospitalier. Pendant cette période, 13 928 femmes présentant un avortement incomplet ont été admises dans les 22 hôpitaux. Le recours à l'aspiration manuelle pour traiter les avortements incomplets du premier trimestre est passé de 38% à 68% des cas (p<0,0001). Les consultations de planification familiale ont également augmenté, de 31% à 78% des femmes (p<0,0001), et la proportion de femmes choisissant une méthode contraceptive avant de quitter l'hôpital est passée de 20% à 49% (p<0,0001). Une infection était associée avec 71% des avortements incomplets, dont 90% étaient septiques. Neuf décès ont été enregistrés et 768 femmes ont présenté de graves complications, un niveau inchangé pendant la période de l'étude. Il reste encore beaucoup à faire au Guatemala pour institutionnaliser les soins post-avortement et réduire la mortalité et les complications, mais nos activités pourront servir à d'autres.

Resumen

En este artículo se describe un programa para ampliar los servicios de atención postaborto (APA) en 22 de los 33 hospitales distritales del sector público en Guatemala, desde julio de 2003 hasta diciembre de 2004. Las principales intervenciones fueron fortalecer los conocimientos y la capacidad técnica del personal; ampliar los servicios de APA; mejorar la infraestructura relacionada con la APA; distribuir material informativo e instituir un sistema de vigilancia de abortos. Un facilitador apoyó el trabajo mediante visitas mensuales de una semana de duración a cada hospital. Además, se prestó atención a desarrollar consenso institucional para apoyar la APA a nivel del gobierno, de los hospitales distritales y del personal hospitalario. Durante este período, 13,928 mujeres con aborto incompleto ingresaron en los 22 hospitales. El uso de la aspiración manual endouterina para el tratamiento del aborto incompleto en el primer trimestre aumentó del 38% al 68% de los casos (p<0.001). También aumentó la provisión de consejería sobre la planificación familiar, del 31% al 78% de las mujeres (p<0.001); y la proporción de mujeres que seleccionaron un método anticonceptivo, del 20% al 49% (p<0.001). El 71% de los abortos incompletos presentaron infección; de estos, el 90% eran sépticos. Hubo nueve muertes y 768 mujeres presentaron complicaciones graves, cuyo nivel permaneció igual a lo largo del estudio. En Guatemala aún falta mucho por hacer para institucionalizar completamente la atención postaborto y disminuir las muertes y complicaciones, pero nuestros logros hasta la fecha serán de utilidad para otros.

Clandestine and unsafe abortion continues to be an important public health problem in many developing countries. High rates of maternal mortality are due in no small part to mortality caused by complications of unsafe abortions – one of the three leading causes of maternal deaths worldwide.Citation1 In addition, the hospital costs of treating abortion complications are an economic burden for limited (and often threatened) government health budgets.Citation2 Although more and more evidence reveals the huge effect unsafe abortion has on health systems, there have been few successful efforts to implement strategies that have successfully reduced complications associated with unsafe abortions at a national level. Post-abortion care in settings where abortion is unsafe, a strategy whose development began three decades ago, seeks to integrate within the national health system the introduction of adequate and timely emergency treatment for retained products after an incomplete abortion, the provision of health education and counselling to help to relieve women's anxiety before and after the procedure, the offering of an effective contraceptive method before a woman leaves hospital, linking women to reproductive and other health services in the community and prevention of unsafe abortion and unplanned pregnancies.Citation3Citation4

Often in the reproductive health field, and more specifically in post-abortion care programmes, the results of operations research or pilot projects have not prompted policymakers to scale up implementation to the national level. Most of the research on post-abortion care during the last decade has been operations research. Billings and Benson provide an invaluable review of the accomplishments of public hospitals in seven Latin American countries in institutionalising the provision of the main elements of PAC.Citation5 However, they found no examples where post-abortion care programmes had been scaled up throughout the national health system, or where a pilot initiative had become government policy.Citation6 Instead, the landscape is littered with successful post-abortion care pilot projects that have evolved no further.

A survey in 2000 shows a maternal mortality ratio of 153 deaths to 100,000 live births in the Republic of Guatemala. In rural areas the ratio was 83% higher, with the number of maternal deaths estimated at 651 to 100,000 live births nationwide. In Guatemala, abortion accounts for at least 10% of maternal deaths and is the fourth largest cause of maternal death.Citation7 From July 2003 to June 2005, there were an estimated 18,965 incomplete abortions in 22 district hospitals in Guatemala and 12 deaths related to these abortions. Reducing maternal mortality continues to be one of the principal priorities identified by the Guatemalan Ministry of Public Health in its policies and work plans.

Currently under Guatemalan law, elective abortion is permitted only to save the life of the woman.Citation8 Consequently, abortion is often performed in secrecy and under unsafe conditions, often leading to serious adverse health consequences, including death. The National Programme on Reproductive Health (Programa Nacional de Salud Reproductiva or PNSR), the Unit of Hospital Service Provision, Tertiary Level of Care (Unidad de Provisión de Servicios III or UPS III) and the Epidemiological Research Centre on Sexual and Reproductive Health (Centro de Investigación Epidemiológica en Salud Sexual y Reproductiva or CIESAR), an independent Centre affiliated with the Ministry of Public Health, have collaborated to position provision of PAC strategically within the Ministry of Public Health's overall framework of reducing maternal mortality.

In 1996, the Epidemiological Research Centre on Sexual and Reproductive Health, with the support of the Ministry of Public Health, began a series of courses for training of trainers, for teams of doctors and nurses, in the concepts and selected technical aspects of post-abortion care, at the country's two teaching hospitals. The week-long course included post-abortion assessment and diagnosis, uterine evacuation procedures and techniques, particularly manual vacuum aspiration (MVA), pain management, infection prevention, management of complications, counselling, referral to other reproductive health services, contraceptive counselling and provision, MVA instrument re-use and storage, and post-procedure and follow-up care.

These teams of doctors and nurses, who came from all the district hospitals in the country, attended on the understanding that after the training they would replicate the course in their own hospitals. These initial courses allowed us to introduce the concept of post-abortion care, primarily to specialists in obstetrics and gynaecology, but also to general physicians, who provide much of the maternity care in district hospitals, particularly the after-hours emergency obstetric care. The experience of this training of trainers programme, and the relationships built during it, allowed us to identify the strengths and weaknesses of our training and implementation strategy and to adapt it as we went along.Citation9

Starting in 2003, we began an 18-month period of scaling up the post-abortion care programme. In this article, we present the main results of this effort in 22 of the 33 district hospitals in Guatemala providing maternity services, and outline the major strategies that we used to achieve these results.

Materials and methods

Guatemala is divided politically and administratively into 22 departments. In 2004, Guatemala had about 12.7 million inhabitants and the annual population growth rate was 2.6%, very high in comparison to neighbouring Central American countries.Citation10Citation11Citation12 The majority (65%) of the population live in rural areas and 80% of this rural population live in localities with fewer than 500 inhabitants.Citation13 The health sector is made up of both public and private institutions, non-governmental organisations (NGOs), and a large traditional medicine sector surviving from the Mayan culture, which is found mainly in rural areas among the indigenous population. At the national level, institutional health coverage of the population is as follows: the Ministry of Public Health and Social Assistance 25%, the Social Security system 17%, the Military Health Service 2.5%, NGOs 4% and the private sector 10%. The rest of the population (41.5%) lack access to modern health services and are largely poor, indigenous and rural. The Ministry of Public Health's network of health facilities includes a total of 43 hospitals, 33 of which offer maternal health care services.Citation14

The impact of the training-of-trainers programme was modest. The course was narrowly focused on introducing post-abortion care and on providing clinical training in MVA to providers. 73% of the professionals trained reported that they were carrying out the first MVA procedures ever performed in their hospitals. We have no data from this period on the quality or extent of counselling or contraceptive provision or on the adequacy of the infrastructure of the different hospitals for post-abortion care provision.

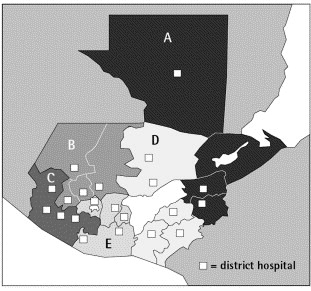

The Epidemiological Research Centre on Sexual and Reproductive Health hired facilitators with leadership skills and training experience. Facilitators' health sector experience varied widely. From 1 July 2003 to 31 December 2004, 22 of the country's 33 district hospitals, one from each of Guatemala's 22 departments, were chosen to participate in the scaling-up programme and divided into five groups (A–E) of four or five hospitals each (see map of Guatemala). The criteria for hospital selection balanced a desire for maximum geographic coverage of the country with the need for facilitators to reach each of the hospitals they were responsible for visiting each month.

Some had business backgrounds, and those with health backgrounds were researchers or doctors (one was a former hospital director). For each group of hospitals, the facilitator would spend a week in each hospital to help implement the interventions and would return to each hospital four or five weeks later, to monitor progress and follow up on the work. The principal interventions implemented with each hospital were:

| • | Strengthening the scientific understanding and technical capacities of hospital staff This involved training in the provision of MVA for uterine evacuation of incomplete abortion of up to 13 weeks of pregnancy, to replace the prevailing less safe and more costly method of dilatation and curettage (D&C),Citation15 instituting post-abortion contraceptive counselling and enabling women to select and obtain a contraceptive method prior to leaving the hospital.Citation16 | ||||

| • | Fostering the development and autonomy of the post-abortion care programme within each hospital This involved monthly coordination meetings with facilitators and Ministry of Public Health personnel, monthly monitoring visits by the facilitator to each district hospital, regional meetings of district hospitals, and the establishment of post-abortion care teams in each hospital made up of both medical and non-medical personnel. The PAC Team would formally be established by the hospital's director and include the head of the Obstetrics and Gynaecology (Ob-Gyn) department, an Ob-Gyn nurse, an administrator, an Ob-Gyn specialist completing his/her final year of training through rural service and a social worker. The PAC team provided post-abortion care services, trained other providers, reviewed achievements and identified areas for improvement. The systematic use of monthly meetings of facilitators, researchers and the technical personnel of the National Programme on Reproductive Health and the Unit of Hospital Service Provision, Tertiary Level of Care, made it possible to identify problems collaboratively and come up with possible solutions in a timely manner. In addition, there were annual meetings in each of the five hospital regions with hospital directors and the key medical and non-medical staff from each hospital. At these meetings, participants shared the advances made in each hospital, developed innovative solutions to common problems, strengthened skills and built teams. These meetings also served to communicate the Ministry of Public Health's commitment to work in the area and to increase the legitimacy and prestige of post-abortion care and thus to build the commitment of the participants. Finally, the Epidemiological Research Centre on Sexual and Reproductive Health, the National Programme on Reproductive Health and the Unit of Hospital Service Provision, Tertiary Level of Care staff carried out additional monitoring and evaluation visits, principally in hospitals encountering problems or that showed little improvement in their progress indicators. | ||||

| • | Strengthening each hospital's infrastructure for post-abortion care Facilitators worked with hospital administrators to set up a dedicated MVA clinic area and provided an initial donation of MVA equipment and of an “MVA cart” for storage of all equipment related to provision of MVA. With this MVA cart, MVA equipment could be stored and moved between the MVA clinic and the emergency service area, as needed. Each district hospital was also given a storage box for the different contraceptive methods which was attached to the wall in the area where post-abortion care was being provided. Hospital staff identified this as one of the simplest and cheapest strategies that substantially increased women's use of contraceptive methods before they left the hospital. Facilitators also worked with hospital directors and administrative staff to try and ensure a sufficient and continuous supply of equipment and medical supplies for post-abortion care. | ||||

| • | Developing, testing and distributing informational materials The Epidemiological Research Centre on Sexual and Reproductive Health and the National Programme on Reproductive Health collaborated to create a poster explaining MVA and the basic steps involved in carrying out MVA, a poster listing the basic concepts in adequate counselling, a pocket card with counselling instructions, a promotional key chain and a semi-annual bulletin with the key results from the Post-Abortion Care programme. These materials were targeted largely at hospital staff, and were designed to build skills, knowledge and commitment. | ||||

| • | Instituting an abortion surveillance system and using it to increase provision of post-abortion care With hospital staff, facilitators collected monthly data from each hospital, including the number of women admitted with incomplete abortions, the number and proportion of MVA procedures for incomplete abortions up to 13 weeks of pregnancy, incomplete abortions at 13–20 weeks of pregnancy, women admitted with incomplete abortions receiving contraceptive counselling, women leaving hospital with an effective contraceptive method, and finally data on maternal morbidity and mortality related to unsafe abortion. We defined a serious complication as arising when an incomplete abortion was further complicated by haemorrhage, hypotension, sepsis, retained products, anaemia, uterine perforation or complications of anaesthesia. The hospital manager, director, and medical and non-medical personnel were able to analyse and evaluate the data provided through the surveillance system and to use it to identify where to target improvements. For the first time, the involved hospital personnel had a concrete, quantitative picture of their institution's performance in implementing an improved health practice. Furthermore, the hospital director could compare his or her institution's performance in the post-abortion care programme to that of other hospitals or to the group average. This data system was unusual and stands out in the Ministry of Public Health for its quality and usability. Having quantitative measures demonstrating the performance of the post-abortion care programme was also invaluable in building and solidifying Ministry of Public Health-wide commitment to the work. The Epidemiological Research Centre on Sexual and Reproductive Health and the facilitators played the anchor role in establishing this system and in teaching hospital personnel how and where to obtain the specific data to run and maintain the system. | ||||

Building broad consensus on support for post-abortion care

The Epidemiological Research Centre on Sexual and Reproductive Health and key figures from the National Programme on Reproductive Health and the Unit of Hospital Service Provision, Tertiary Level of Care worked to build consensus among national decision-makers, hospital directors and medical and non-medical hospital personnel about the importance of institutionalising post-abortion care services before, during and after the intervention period. Continual consensus building was considered essential to the implementation and long-term sustainability of these services. The leadership of the Ministry of Public Health had already prioritised efforts aimed at reducing maternal mortality, and more specifically, had committed itself to preventing deaths related to unsafe abortion. Our intervention leveraged already existing standards and guidelines, such as the National Reproductive Health Guidelines, and was further supported during the process of development of the 2005 Obstetric Emergency Guidelines, which emphasised the management and treatment of abortion complications.Citation17Citation18 These policies served to bolster the legitimacy and prestige of post-abortion care work, particularly among district hospital staff. This effort to scale up post-abortion care services was further facilitated by the championing roles of the Epidemiological Research Centre on Sexual and Reproductive Health and key figures from the National Programme on Reproductive Health and the Unit of Hospital Service Provision, Tertiary Level of Care, all within the Ministry of Public Health, and the fact that project management and supervision were shared responsibilities.

Data on delivery of post-abortion care and contraception

Data were collected in the 22 hospitals during the 18-month period on the proportion of MVA procedures performed, the number of women for whom contraceptive counselling was provided, the number of women selecting an effective contraceptive method, and morbidity and mortality related to unsafe abortion reported. The statistical software package StatsDirect 2.4.5 was used to calculate a Chi2 for linear trend to evaluate the statistical significance of the results.

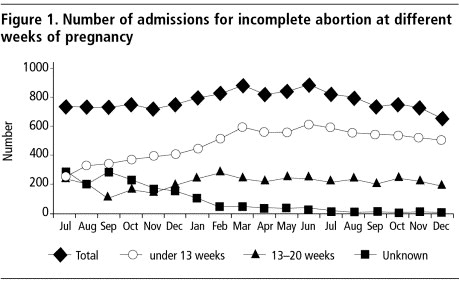

From July 2003 to December 2004, the twenty-two district hospitals admitted a total of 13,928 women with incomplete abortions (approximately 66% of women with incomplete abortion treated nationally in the government health care system in Guatemala). shows the number of women with incomplete abortions treated according to number of weeks of pregnancy each month. The ability of hospital personnel to diagnose the length of pregnancy for incomplete abortions at admission and to record the diagnosis in the clinical records improved over the study period. Hence, the number of incomplete abortions identified as being less than 13 weeks of pregnancy increased during the study period and the number of abortions with unknown length of pregnancy decreased, while the number of second trimester abortions remained about the same.

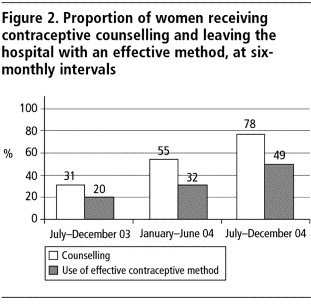

The district hospitals increasingly began providing counselling before, during or after MVA procedures. presents the results at six-month intervals. The proportion of women counselled had improved at each six-month interval, from 31% to 55% and finally 76% (linear trend p<0.0001). There was a similar improvement in the number of women selecting an effective contraceptive method before leaving the hospital, from 20% to 32% and finally 49% (linear trend p<0.0001). At the end of the 18-month period, half of the women admitted for incomplete abortion left the hospital with an effective contraceptive method, either an injectable (61%), the pill (23%), male condoms (4%), female sterilisation (5%), IUD (3%) or a natural family planning method (4%). This contraceptive method mix is comparable to that among Guatemalan women nationwide.Citation19

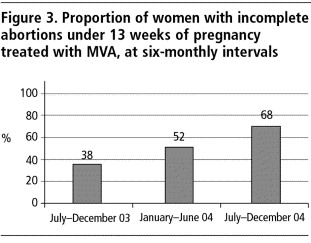

shows the proportion of MVA procedures carried out for the 8,359 women with incomplete abortions at up to 13 weeks of pregnancy, at six-monthly intervals. The proportion increased from 38% to 52% and finally 68% of these abortions (linear trend p<0.0001).

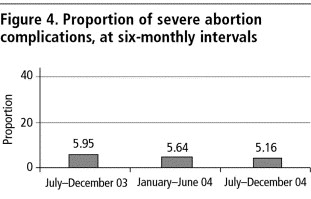

Lastly, of the total of 13,928 women admitted with incomplete abortions during the study period, there were nine abortion-related deaths, giving an abortion mortality rate of 6.4 per 10,000 women admitted to the 22 hospitals for incomplete abortion. A further 768 women (6%) suffered severe complications, and the level of severe complications remained practically unchanged, from 5.95% to 5.64% and 5.16% (linear trend p=0.445) over the study period (). Of the 13,928 women, 71% of the incomplete abortions were related to infection, and of these, 90% were diagnosed with septic abortion.

Many of the women with incomplete abortions who do reach a district hospital arrive either too late for treatment or when sepsis, infection and/or haemorrhaging are extreme. They are delayed by a host of factors, including the distance to travel to hospitals, finding transportation, poverty, cultural norms that prohibit receiving care from a male doctor, and the stigma associated with seeking post-abortion care. The women receiving care at public facilities are more often indigenous, poorer and less educated than those receiving private health care. Because of these and other barriers, many women with incomplete abortions never reach hospital for care. A 2003 survey of health care providers estimated that almost 40% of rural and indigenous women with incomplete abortions do not receive any hospital care.Citation20

Discussion

Until recently the literature on scaling-up has not focused on reproductive health,Citation21Citation22 and much work is still needed to clarify definitions and models in order to determine the most effective strategies for scaling up reproductive health programmes. While scaling up can be seen as project replication or programme expansion, i.e. expanding the number or sites or locations with services and the number of people served,Citation23 the present project adds to this definition the translation of a small-scale initiative into a government policy. The major steps for a successful scaling up project and lessons learned have been discussed in the literature.Citation22Citation24Citation25 The following are the aspects we believe to have been particularly significant in our experience in Guatemala: the building of political consensus and will, the strengthening of hospital management through regular meetings, regular review of abortion data by hospital staff, the leadership of the Ministry of Public Health and the provision of training, technical assistance and informational materials.

In Guatemala, abortion has traditionally evoked tremendous stigma, and MVA is negatively linked in many minds with increased provision of induced abortion. Our approach of promoting post-abortion care (and MVA) as a public health strategy to reduce maternal mortality has been critical. In addition, we believe that the fact that this work has been initiated and driven from within Guatemala's Ministry of Public Health and not initiated by an external donor or agency, has made galvanising commitment easier. The use of data on incomplete abortion has also been a critical aid to our efforts. It was unprecedented for hospital directors to receive timely (monthly) data on the progress of adopting an improved public health care approach, and we believe it helped greatly in building broader commitment across the Ministry of Public Health as the intervention continued.

In a relatively short period of time, a significant improvement in provision of post-abortion care services in the national programme was observed, including the increased use of MVA as the standard of care in treating incomplete abortion up to 13 weeks of pregnancy and in the availability and provision of contraceptive counselling and methods on site. Our data suggest that over the study period hospital personnel improved their ability to diagnose the number of weeks of pregnancy at admission for incomplete abortion, as well as to record their diagnosis in the clinical records. MVA treatment went from being provided 38% of the time to 68%, and the proportion of women admitted for incomplete abortions who left the hospital with an effective contraceptive method more than doubled. We do not yet have follow-up data on contraception continuation rates or subsequent contact with the health system, but more effort in this area is needed.

Overall, our intervention has achieved advances in institutionalising three of the five pillars of post-abortion care in a setting where abortion is legally restricted and unsafe. We still need to link women to reproductive and other health services in the community and to work at the community level to prevent unsafe abortion and unplanned pregnancies.

Although the Guatemalan health authorities have taken important steps towards improving the quality of women's care by introducing post-abortion care in two-thirds of the country's district hospitals, there was no reduction in abortion-related mortality or serious morbidity. However, this intervention allowed, for the first time, details of the type and number of complications related to unsafe abortion in women admitted to the majority of district hospitals in Guatemala to be recorded. Our hope is that if women know that they can come to the hospitals for post-abortion care, and can reach the hospitals without delay, complications may more easily be prevented or prevented from becoming worse. However, we do not yet have evidence of this.

We have meanwhile continued the efforts to scale up post-abortion care and as of the end of 2005, are collaborating with all 33 district hospitals in the country, as well as with Guatemala's two teaching hospitals. It will be crucial to ensure full implementation of post-abortion care services throughout the country, not just at the hospital level, but also move the provision of post-abortion care to health centres. There also remains a strong need to link women to reproductive and other health services in the community and to work at the community level to prevent unsafe abortion and unplanned pregnancies. These efforts will require public education campaigns on the serious consequences of unsafe abortion and the importance of seeking post-abortion care, the promotion of broader public discussion on the abortion issue, and the access of women and men to effective and safe contraceptive methods.

Women's deaths due to unsafe abortion complications among the study population are all the more troubling because they are avoidable, and our statistics understate the gravity of the situation.Citation1 By contrast, in the United States, between 1988–1997 the overall death rate for women obtaining legally induced abortions was 0.7 per 100,000 abortions.Citation26

Even after 18 months of intensive work and many improvements, fully institutionalising post-abortion care services, making them sustainable, and ensuring the availability of MVA equipment and contraceptive methods remains a challenge. Hospitals are still working to build the purchase of MVA equipment into their annual budgets, and the Ministry of Public Health is working to strengthen its contraceptive procurement and distribution systems. In addition, given the turnover of hospital staff, there is a need to incorporate post-abortion care training as an integral part of the basic medical education of physicians and nurses. We have since commenced work in this area through collaboration with the country's two teaching hospitals.

We hope that further expansion of the post-abortion care programme and greater understanding of the impact of abortion complications on women's health will strengthen commitmentCitation27 to the programme and its sustainability in future. In the area of post-abortion care, investigation of the transfer of knowledge and technical capacity from small hospital projects to full national hospital systems has not typically been considered a relevant domain for investigation. Hospital-based post-abortion care training projects are immensely valuable in countries with conditions similar to Guatemala's, and we hope our efforts to date will be valuable for others.

Acknowledgements

This publication would not be possible without the participation of the committed health professionals of the national health system of Guatemala. We would also like to recognise the hospital facilitators – Francisco Ramírez, Leonardo Ortuño, Consuelo Arriola, Roberto Flores, Ivannova Ruiz, Marisol Sandoval and María del Rosario Najera – for their tireless work to support and encourage hospitals in the adoption of post-abortion care. Finally, we are grateful for the support of the Erik E and Edith H Bergstrom Foundation and especially Sarah Jane Holcombe for review and comments on the original manuscript.

References

- World Health Organization. Unsafe Abortion: Global and Regional Estimates of Instances of Unsafe Abortion and associated Mortality in 2000. 4th ed., 2004; WHO: Geneva. At: <http://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/unsafe_abortion_estimates_04/estimates.pdf. >.

- BR Johnson, J Benson, J Bradley. Costs of Alternative Treatments for Incomplete Abortion. World Bank Working Paper. 1993; World Bank: Washington, DC.

- E Hardy, K Herud. Effectiveness of a contraceptive education program for post abortion patients in Chile. Studies in Family Planning. 6(7): 1975; 188–191.

- Postabortion Care Consortium Community Task Force. Essential Elements of Postabortion Care: An Expanded and Updated Model. PAC Consortium. July. 2002. At: <www.pac-consortium.org/Pages/pacmodel.htm. >.

- D Billings, J Benson. Postabortion care in Latin America: policy and service recommendations from a decade of operations research. Health Policy and Planning. 20(3): 2005; 158–166.

- R Kohl, L Cooley. Scaling up a conceptual and operational framework. A preliminary report to the MacArthur Foundation's Program on Population and Reproductive Health. 2005; Management Systems International.

- Ministerio de Salud Pública y Asistencia Social. Informe Final. Línea Basal de Mortalidad Materna para el año 2000. Marzo. 2003; MSPAS: Guatemala.

- Guatemala Penal Code Decree No.17-73, Art.133, 137, 1999.

- E Kestler, L Valencia. Disponibilidad y Calidad de la Atencion del Postaborto en Guatemala. 2004; Editorial F&G Editores: Guatemala.

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística. Guatemala: proyecciones de población a nivel departamental y municipal por año calendario, período 2000–2005. 2001; Instituto Nacional de Estadística: Guatemala.

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística. Encuesta Nacional de Salud Materno Infantil 1998–99. 1999; INE, MSPAS, USAID, UNICEF, DHS: Guatemala.

- Centro Legal para Derechos Reproductivos y Políticas Públicas. Mujeres del Mundo: Leyes y Políticas que Afectan sus Vidas Reproductivas. 1997; CRLP: New York.

- Organización Panamericana de la Salud. Mejorando la salud de los pueblos de las Américas. Perfiles básicos de salud, resúmenes 1999. At: <www.paho.org>.

- Red de Servicios de Salud. Ministerio de Salud Pública, República de Guatemala, Publicación Interna. 2000; Unidad de Programación, Ministerio de Salud Pública: Guatemala.

- F Forna, AM Gülmezoglu. Surgical procedures to evacuate incomplete abortion (Cochrane Review). The Reproductive Health Library, Issue 8. 2005; Update Software Ltd.: Oxford. At: <http://www.rhlibrary.com. >.

- O Farfan, E Kestler, M Abrego de Aguilar. Información y consejeria en planificación familiar postaborto. Experiencia en cuatro hospitales de Centro-América. Revista Centro Americana de Ginecología y Obstetricia. 7(2): 1997; 46–56.

- Ministerio de Salud Pública y Asistencia Social. Programa Nacional de Salud Reproductiva. 2003; Protocolos de Salud Reproductiva: Guatemala, 21–26.

- Ministerio de Pública y Asistencia Social. Programa Nacional de Salud Reproductiva. 2005; Guía de Manejo de Emergencias Obstétricas: Guatemala, 66–69.

- Ministerio de Salud Pública de Guatemala. Expandiendo Opciones en Salud Reproductiva. Diagnóstico para Identificar Intervenciones Prioritarias que Mejoren el Acceso y la Calidad de los Servicios Básicos de Salud Materna en Guatemala. 2002; World Health Organization, Panamerican Health Organization: Geneva.

- E Prada, E Kestler, C Sten. Abortion and Postabortion Care in Guatemala: a report from health care providers and health facilities. Occasional Report. 2005; Guttmacher Institute: New York. No. 18.

- Simmons R, Schiffman J. Scaling Up Reproductive Health Service Innovations: A Conceptual Framework. Paper prepared for the Bellagio Conference: From Pilot Projects to Policies and Programmes. 21 March–5 April 2003. November 2002.

- R Simmons, J Brown, M Díaz. Facilitating large-scale transitions to quality of care: an idea whose time has come. Studies in Family Planning. 33(1): 2002; 61–75.

- P Uvin. Fighting hunger at the grassroots: paths to scaling up. World Development. 23(6): 1995; 927–939.

- F Gonzáles, E Arteaga, L Howard-Grabman, BR Burkhalter, VL Graham. Scaling up the WARMI project: lessons learned mobilizing Bolivian communities around reproductive health. 1999; USAID by the CORE Group, Washington DC and Basic Support for Institutionalizing Child Survival Project: Arlington VA.

- M Sternin, J Sternin, M David. Scaling up a poverty alleviation and nutrition program in Vietnam. T Marchione. Scaling Up, Scaling Down: Overcoming Malnutrition in Developing Countries. 1999; Gordon and Breach: Australia, 97–117.

- L Bartlett, C Berg, H Shulman. Risk factors for legal, induced abortion–related mortality in the United States. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 103: 2004; 729–737.

- Kestler E, Valencia L, Del Valle V, Silva A. Calidad de la prestación de servicio en la atención postaborto en Guatemala. Unpublished paper, 2005.