Abstract

Adolescent sexuality is a highly charged moral issue in Kenya and Zambia. Nurse-midwives are the core health care providers of adolescent sexual and reproductive health services but public health facilities are under-utilised by adolescents. The aim of this study was to investigate attitudes among Kenyan and Zambian nurse-midwives (n=820) toward adolescent sexual and reproductive health problems, in order to improve services for adolescents. Data were collected through a questionnaire. Findings revealed that nurse-midwives disapproved of adolescent sexual activity, including masturbation, contraceptive use and abortion, but also had a pragmatic attitude to handling these issues. Those with more education and those who had received continuing education on adolescent sexuality and reproduction showed a tendency towards more youth-friendly attitudes. We suggest that critical thinking around the cultural and moral dimensions of adolescent sexuality should be emphasised in undergraduate training and continuing education, to help nurse-midwives to deal more empathetically with the reality of adolescent sexuality. Those in nursing and other leadership positions could also play an important role in encouraging wider social discussion of these matters. This would create an environment that is more tolerant of adolescent sexuality and that recognises the beneficial public health effect for adolescents of greater access to youth-friendly sexual and reproductive health services.

Résumé

La sexualité des adolescents est une question morale très sensible au Kenya et en Zambie. Les services de santé génésique pour adolescents sont assurés principalement par des infirmières/sages-femmes, mais les centres publics sont sous-utilisés par les adolescents. Cette étude a enquêté sur les attitudes des infirmières/sages-femmes kényennes et zambiennes (n= 820) à l'égard des problèmes de santé génésique des adolescents, afin d'améliorer les services. Les données ont été recueillies par un questionnaire. L'étude a révélé que les infirmières/sages-femmes désapprouvaient l'activité sexuelle des adolescents, notamment la masturbation, l'utilisation de contraception et l'avortement, mais qu'elles traitaient ces questions de manière pragmatique. Les plus instruites et celles qui avaient reçu une formation continue sur la santé génésique des adolescents tendaient à avoir une attitude plus bienveillante. À notre avis, la formation initiale et continue devrait mettre l'accent sur la pensée critique autour des dimensions culturelles et morales de la sexualité des adolescents, pour aider les infirmières/sages-femmes à être plus ouvertes à la réalité de la sexualité des adolescents. Les responsables des soins infirmiers et d'autres secteurs pourraient également jouer un rôle important afin d'élargir la discussion sociale sur ces questions. Cela créerait un environnement plus tolérant à l'égard de la sexualité des adolescents et ferait prendre conscience des effets bénéfiques sur la santé publique d'un accès élargi à des services de santé génésique adaptés aux jeunes.

Resumen

La sexualidad de los adolescentes es un asunto moral muy cargado en Kenia y Zambia. Las enfermeras-obstetrices son los principales prestadores de atención a la salud sexual y reproductiva de los adolescentes, quienes infrautilizan los servicios de salud pública. El objetivo de este estudio fue investigar las actitudes entre las enfermeras-obstetrices de Kenia y Zambia (n= 820) hacia los problemas relacionados con la salud sexual y reproductiva de los adolescentes, a fin de mejorar los servicios que éstos reciben. Se recolectaron datos mediante un cuestionario. Los resultados indicaron que las enfermeras-obstetrices se oponen a la actividad sexual en la adolescencia, como la masturbación, el uso de anticonceptivos y el aborto, pero también manifestaron una actitud pragmática hacia manejar estos asuntos. Aquéllas con más preparación y las que habían recibido educación continua sobre la sexualidad y reproducción de los adolescentes se inclinaban a tener actitudes más amigables hacia la juventud. Sugerimos que en la capacitación pre-grado y en la educación continua se haga hincapié en el pensamiento crítico en torno a las dimensiones culturales y morales de la sexualidad de los adolescentes, con el fin de ayudar a las enfermeras-obstetrices a sobrellevar con empatía la realidad de la sexualidad de los adolescentes. Aquellos en enfermería y otros puestos de liderazgo también podrían desempeñar una función importante para motivar un debate social más amplio sobre estos asuntos. Esto crearía un ambiente más tolerante de la sexualidad de los adolescentes, en el cual se reconoce el efecto benéfico de ampliar el acceso a los servicios de salud sexual y reproductiva amigables a la juventud.

Unwanted pregnancy, unsafe abortion, and sexually transmitted infections (STIs), including HIV, are major public health problems in many parts of the worldCitation1 among adolescents and young people aged 15–24. In 1994, adolescent reproductive health and rights was placed on the international agenda for the first time at the International Conference on Population and Development. Despite global agreements, however, reproductive health services remain grossly inadequate and adolescent sexual and reproductive health needs are still a neglected issue in many countries.Citation2

This project was developed to target reproductive health issues among youth, through a network consisting of nurses and nurse-midwives from Kenya, Zambia and Sweden, where nurses' and midwives' encounters with adolescents have been identified as problematic, leading to under-utilisation of sexual and reproductive health services by young people. We decided to study the attitudes in two neighbouring countries which have partly different health systems and different laws on induced abortion. The study described in this paper is part of a larger project aiming at improving sexual and reproductive health services for adolescents in Kenya and Zambia.

Adolescent sexual and reproductive health in Kenya and Zambia

The socio-cultural context in which adolescents in Kenya and Zambia find themselves has changed considerably within the past few generations. In both countries, as in much of Africa, adolescents are experiencing social turmoil resulting from conflicting values as the countries become more industrialised and urbanised. Societal norms on adolescent sexuality vary across ethnic groups. For example, some of the major ethnic groups in the areas where this study took place, such as the Luo in Kenya and the Bemba in Zambia, expect girls to be chaste before marriage. The Cewa in Zambia, on the other hand, allow limited and discrete sexual relations among the young. Most ethnic groups, however, stipulate that young women should not have children out of wedlock.Citation3Citation4Citation5 Both Kenya and Zambia have strong religious leanings. The predominant religion in both countries is a blend of traditional beliefs and Christianity and a minor part of the population adheres to Islam.Citation6 Regardless of religious affiliation, premarital sex is prohibited. Sex education, which formerly rested on the elderly within families, is increasingly being taken over by schools, churches and non-governmental organisations (NGOs). These institutions often have differing agendas, which result in conflicting messages. Some, especially NGOs, advocate condom use for sexually active youth, while others, particularly religious organisations, stress abstinence before marriage.Citation7 Furthermore, modernisation has prolonged the process of formal education and postponed the age at marriage. Although most adolescents say they disapprove of premarital sex, since it is considered sinful, many of them are sexually active due to being in love and wishing to experiment.Citation8

In Kenya, the median age at first sexual intercourse is 17 years for both boys and girls;Citation9 in Zambia, for boys the median age is 18 years and for girls 17 years.Citation10 Poverty is another reason why girls engage in premarital sex. In Kenya, 21% of adolescent girls have received money, gifts or favours for sex, while 17% of adolescent boys have paid for sex.Citation9 The corresponding figures in Zambia are 40% for boys and 27% for girls.Citation11

Governmental policy, in both Kenya and Zambia, is to provide all sexually active men and women with contraceptive services,Citation12Citation13 but in reality, adolescents have limited access to such services.Citation14Citation15 This leaves adolescents with periodic abstinence as their only protective option, and adolescent pregnancy as a growing concern.Citation14 For instance, adolescent childbearing has been identified as a major cause of school drop-out in Kenya as well as in Zambia.Citation16Citation17 The desire to continue education was found to be the main reason why Zambian unmarried girls resorted to induced abortion. Although, abortion is legal in Zambia, adolescents undergo illegal abortions because legal abortion services are inaccessible and unacceptable.Citation16 Findings from Western Province of Zambia revealed that one in 100 schoolgirls dies from abortion-related complications. Hospital-based studies in Nairobi, Kenya, have shown that unsafe abortion accounts for about 35% of maternal deaths.Citation18 Furthermore, the consequences of unprotected sex are clearly reflected in the high prevalence of HIV among adolescents in both countries. Nyanza Province in Kenya, where part of this study took place, has the highest rate of HIV infection in the country, 14% among men and women aged 15–49 years. The HIV prevalence in adolescents aged 15–19 is about 2%.Citation9 The Copperbelt Province in Zambia, where this study was carried out, has the second highest HIV prevalence (20%) among the general population, and about 5% of adolescents aged 15–19 years are HIV-positive.Citation19 Hence, some adolescents engage in unprotected premarital sex with devastating consequences despite the moral prohibitions.

Nurse-midwives providing sexual and reproductive health care

In east and southern Africa, nurses and nurse-midwives form the largest number of health care providers and are the most common category of health personnel that adolescents meet for their sexual and reproductive health needs.Citation20 Services include counselling and treatment related to STI, including HIV, and provision of contraception. Moreover, nurse-midwives provide maternal and child health care services,Citation21 as well as abortion care, which is, however, very restricted.Citation22

Public health services are largely available in both countries, but under-utilised by adolescents for various reasons. Confidentiality as well as health providers' attitudes are two important issues affecting whether or not young people will use health facilities.Citation23 Studies from Kenya and Zambia indicate that staff behaviour discourages young people from attending clinics or for follow-up visits. For instance, young STI patients turn preferably to traditional healers due to the insensitive attitudes of health professionals, and adolescents face difficulties obtaining contraceptives at public health facilities.Citation23Citation24Citation25 Abortion is a highly sensitive issue, and young women who seek abortion or post-abortion care commonly encounter negative staff attitudes.Citation26Citation27

Personal values and views of health professionals, including nurse-midwives, may affect quality of care as well as the accessibility of services. It is therefore important to increase our understanding of the attitudes of these providers, and if needed, to find ways to change unfavourable attitudes in order to be able to encourage adolescents to utilise health services for their sexual and reproductive health needs. The aim of this study was to investigate the attitudes of nurse-midwives in Kenya and Zambia towards adolescent sexuality and related reproductive health problems in order to improve sexual and reproductive health services for adolescents.

Methodology

A cross-sectional survey of nurse-midwives working in sexual and reproductive health services in two districts each in Kenya and Zambia was conducted between September–December 2001.

Ethics committees in Kenya, Zambia, and Sweden approved the study. Prior to data collection, the nurse-midwives invited to participate were informed about the aims of the study, that their participation was voluntary, and that they had the right to withdraw at any time.

The study was carried out in urban and rural areas of Nakuru and Kisumu districts in Kenya, embracing 15 divisions, of which the ten largest divisions were selected to constitute the sampling frame. In Zambia, Kitwe and Ndola districts, which are mainly urban areas, constituted the sampling frame. The predominant ethnic groups in the study areas were Luo, Kikuyu and Kalenjin in Kenya, and Bemba in Zambia. However, health personnel in both countries come from a variety of ethnic groups since they are recruited from different parts of the country.

The main inclusion criteria for this study were that participants should be trained nurses, midwives or nurse–midwives (labelled for simplicity throughout this paper as nurse-midwives) working in adolescent sexual and reproductive health services in the selected areas. All available participants, including nightshift staff, received a questionnaire to respond to in privacy. To keep participation anonymous, no names were marked on the questionnaires.

In Kenya, 420 of approximately 600 enrolled nurse-midwives (ENMs) and registered nurse-midwives (RNMs)Footnote* working with sexual and reproductive health service in the study area were recruited from hospitals and from governmental and private health centres. Remote and minor health facilities with only one to three nurse-midwives were excluded due to logistic reasons. In Zambia, 400 of approximately 450 ENMs and RNMs working with sexual and reproductive health services in the study area were recruited from hospitals and governmental and private health centres.

A group of midwifery researchers from Sweden and sub-Saharan Africa (including three of the co-authors) designed a questionnaire on nurse-midwives' attitudes towards adolescent sexual and reproductive health problems, based on their clinical experience. The questionnaire was in English, which is the official language in both countries. It was piloted with a group of midwives working in reproductive health services at Nairobi Hospital in Kenya, and Central Hospital in Kitwe, Zambia, and presented in Cape Town, South Africa, in 2001 at a workshop for African and European health professionals dealing with adolescent reproductive health matters, to find out if the concepts and expressions used in the questionnaire were easily understood. The final questionnaire consisted of background data and 41 statements. In this study, we focus on 17 of those statements, which were related to adolescent sexuality, contraceptive use, pregnancy and abortion, and promiscuity.Footnote* Each statement was assigned four response choices: disagree completely, disagree, agree, or agree completely.

Attitudinal scales have well-known limitations in measuring complex phenomena, but they can be useful to get an overall picture from large groups. To avoid bias produced by response tendency and to enhance internal validity, both positively and negatively worded statements were included in our instrument. Furthermore, we wanted the participants to take a clear stand on each statement, so we decided to leave out a “neither-nor” alternative. A four-point response format is useful when studying changes in attitudes over time, such as before and after an intervention, when a fine-tuned instrument is needed. However, in this cross-sectional study, in order to highlight general directions and get a clearer overview of respondents' attitudes, statements were aggregated into a two-point response format in which the responses “disagree” and “disagree completely” and “agree” and “agree completely” were each combined.

SPSS v.10 for Windows, was used for statistical analysis. Descriptive data on nominal level is demonstrated by cross tables. Data on interval level are presented as median. Chi-square test was used in analyses that entailed comparisons of proportions. Significance level was set at 0.05.

The results were grouped into four themes: adolescent sexuality, contraceptive use, pregnancy and abortion, and promiscuity. Results from the two countries are presented separately under each theme. The attitudes were also analysed by continuing education in sexual and reproductive health, and enrolled and registered nurse-midwife. As regards any differences according to age, we found extremely weak and few differences in attitudes between different age groups, and the differences we did find did not show any particular tendency. In one statement, the younger nurse-midwives were more restrictive and in another, the older ones. We therefore decided not to present these results. Furthermore, no differences in attitudes were found between nurse-midwives according to religion. Only statements showing a significant difference in relation to these background variables are presented.

Response rate

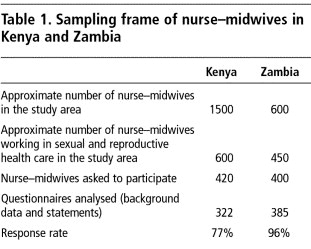

In Kenya, 420 nurse-midwives were asked to participate. Ninety-eight did not reply to either the background or attitudinal section of the questionnaire. For those we have no further information. Hence, data were analysed from 322 nurse-midwives, a response rate of 77% (Table 1). In Zambia, 400 nurse-midwives were asked to participate, of whom 15 did not reply to either part of the questionnaire and for those we have no more information. Hence, data were analysed from 385 nurse-midwives, a response rate of 96% (Table 1).

Reasons for not filling in the questionnaires were lack of time and large distances to the health centres, which made it difficult for research assistants to remind nurse-midwives to complete the questionnaire. The latter was particularly the case in Kenya. The non-response rate on single statements ranged from 1–15 statements (5%) in Kenya and from 1–8 statements (2%) in Zambia.

Participants

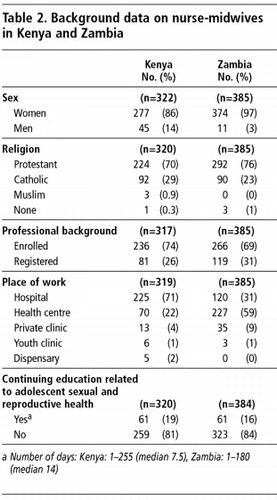

In both countries, the large majority of nurse-midwife participants were women. In Kenya, the age range was 22–54 years (median 37), and in Zambia respondents were 22–60 years old (median 39). Due to differences in the structure of the two health systems, and the fact that a number of smaller health centres (mainly in Kenya) were not included in the sampling frame, place of work differed between the two countries. In the Kenyan setting, most nurse-midwives worked in hospitals, while in Zambia, most nurse-midwives worked in health centres. In Kenya, respondents had spent between 1–39 years in the profession (median 12 years) and in Zambia 1–34 years (median 15 years). The majority of nurse-midwives in both countries had not received any continuing education related to adolescent sexual and reproductive health issues (Table 2).

Attitudes toward adolescent sexual and reproductive health problems

Adolescent sexuality

The majority of nurse-midwives in both countries (Kenya 77%, Zambia 81%) agreed that “their first option would be to recommend unmarried adolescent boys and girls to abstain from sex when they ask for contraceptives”. Nearly all Kenyan (95%) and Zambian (94%) nurse-midwives disagreed with that “it is more important for boys to have sexual experience before marriage than for girls”. Likewise, over 96% in both countries disagreed that “adolescent boys and adolescent girls should be left free to satisfy their sexual needs”.

Regarding masturbation,Footnote* a majority of Kenyan (82%) as well as Zambian (86%) nurse-midwives agreed that “adolescent boys should be taught the danger of masturbation”. Furthermore, 72% and 63% in Kenya and Zambia, respectively, disagreed that “masturbation is a good way to prevent unwanted pregnancies and STI/HIV for girls”.

Contraceptive use

About two-thirds (69%) of Kenyan and about half (52%) of Zambian respondents disagreed that “16-year-old out-of-schoolFootnote* girls should be encouraged to use condoms”. However, both Kenyan (55%) and Zambian (67%) nurse-midwives agreed that “if a schoolgirl was sexually active she should be allowed to use contraceptives”.

Regarding counselling on condoms, about half of respondents (54%) in Kenya and two-thirds (68%) in Zambia, agreed that “out-of-school boys should be informed about how to use a condom”. Yet 59% of Kenyan and 47% of Zambian respondents disagreed that “schoolboys asking for condoms show responsibility”.

Pregnancy and abortion

A large majority of respondents in Kenya (88%) and Zambia (87%) agreed that “a pregnant girl should be allowed to continue school”, and similar majorities (Kenya 83%, Zambia 84%) disagreed that “a schoolboy who impregnates a girl should be expelled from school”.

As regards abortion, the majority from both countries (Kenya 80%, Zambia 94%) disagreed that “abortions should be allowed for adolescent girls with unwanted pregnancies”. Yet 59% of Kenyan and 50% of Zambian nurse-midwives disagreed that they “would feel annoyed if an adolescent girl presents with symptoms from induced abortion”.

Promiscuity

In Kenya, more than half of respondents disagreed that “a secondary schoolboy (56%) or schoolgirl (55%) with a genital ulcer is likely to be promiscuous”. In Zambia, the corresponding figures were 37% for schoolboys and 40% for schoolgirls. Furthermore, 67% of Kenyan and 46% of Zambian respondents agreed that “out-of-school adolescents are more likely to be promiscuous than adolescents in school”.

Comparison of attitudes of nurse-midwives with and without continuing education

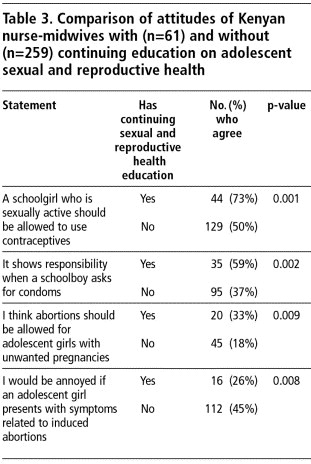

In Kenya, significantly more male nurse-midwives (31%) compared to female nurse-midwives (17%) had received continuing education related to adolescent sexual and reproductive health (p= 0.026). In general, significantly more nurse-midwives with continuing education agreed with adolescent contraceptive use. At the same time, with or without continuing education, most disapproved of abortion. However, these attitudes were significantly less frequent in the group with continuing education (Table 3).

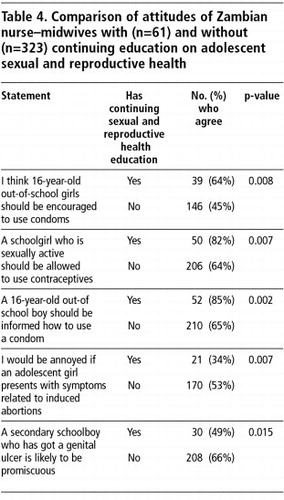

In Zambia, more male (27%) than female (16%) nurse-midwives had received continuing education in adolescent sexual and reproductive health (p= 0.392). In general, significantly more nurse-midwives who had received this education reported more youth-friendly attitudes as related to contraceptive use, abortion and genital ulcer compared to those without this education (Table 4).

Comparison of attitudes of enrolled and registered nurse-midwives

In Kenya, fewer enrolled nurse-midwives (28%) than registered nurse-midwives (40%) agreed that “a 16-year-old out-of-school girl should be encouraged to use condoms” (p=0.049). However, more enrolled nurse-midwives (48%) than registered nurse-midwives (32%) agreed that “a secondary schoolboy with a genital ulcer is likely to be promiscuous” (p=0.013).

In Zambia, fewer enrolled nurse-midwives (85%) than registered nurse-midwives (93%) agreed that “a girl who becomes pregnant should be allowed to continue school” (p=0.018).

Discussion

Our findings locate nurse-midwives providing adolescent sexual and reproductive health services at a critical intersection between the norms and values of the community – which advocates sexual abstinence before marriage – and the reality of adolescent premarital sex, and adolescent' need for condoms, contraceptives and abortion. Although this study was based in four districts in Kenya and Zambia, nurse-midwives in both countries are recruited from different parts of the country and rotate on a regular basis between health clinics, and are thus being exposed to both rural and urban areas. Our findings may therefore be generalised to other parts of Kenya and Zambia, where individuals share the same cultural background as respondents in the present study. Overall, both Kenyan and Zambian nurse-midwives reported similar attitudes and we make the following recommendations for both countries:

| • | Conflicting perspectives on adolescent sexuality That adolescent sexuality is a highly charged moral issue in Kenya and Zambia was confirmed in this study. In general, nurse-midwives from both countries disapproved of adolescent premarital sex, contraceptive use, masturbation and abortion. These are indicative expressions of support for sexual abstinence before marriage and “proper” sexual behaviour, with roots in both culture and religion.Citation3Citation4Citation8 Nonetheless, nurse-midwives also showed a rather pragmatic attitude towards adolescent sexual and reproductive health problems, since a majority approved of contraceptive use by sexually active girls and were prepared to counsel boys on condom use. Furthermore, results from this study showed that nurses-midwives from both countries strongly disapproved of abortion. Interestingly, this was even more common among Zambian respondents, despite the fact that Zambia is one of the few countries in Africa that allows abortion, including on social grounds.Citation22 Studies in Zambia, South Africa and Kenya have shown that health providers are insensitive towards women who terminate unwanted pregnancies.Citation16Citation28Citation29 Rogo in KenyaCitation29 and Koster-Oyekan in ZambiaCitation16 found that health providers strongly opposed abortion for religious and ethical reasons. However, half of respondents in our study would not be annoyed with a girl showing signs of induced abortion. Again, both a condemnatory and a more understanding attitude were reflected in the results. These conflicting perspectives may reflect that nurse-midwives, similar to other health professionals within the area of reproductive health, are at a critical intersection between the norms and values of the community and the reality of adolescents engaging in premarital sex. Their tendency to take a more pragmatic approach could be due to awareness of the severe consequences of unprotected sex for adolescents, which they have to face as health care providers. A study from Vietnam also observed conflicting attitudes among midwifery students as regards adolescent sexuality. These students generally disapproved of adolescent premarital sexual relations and abortion, but at the same time they showed an empathetic attitude and willingness to support young women, who bear the consequences of unwanted pregnancies.Citation30 | ||||

| • | Stimulation of critical thinking in training and education Furthermore, our results show a tendency towards more youth-friendly attitudes among nurse-midwives with greater education and among those who had received continuing education about adolescent sexuality and reproduction. Based on these findings, we suggest that critical thinking around the cultural and moral dimensions attached to adolescent sexuality should be emphasised in undergraduate training as well as in continuing education to help nurse-midwives to deal with the reality of adolescent sexuality. Some of the topics that need to be discussed during training include not only abortion, contraceptive use and adolescent sexuality, but also, considering the severe HIV situation in Kenya and Zambia, negative attitudes to masturbation, not least because masturbation causes no harm and is a form of safer sex. Furthermore, the actual patterns of sexual relationships among adolescents, and the fact that acquiring an STI is not necessarily a sign of “promiscuity”, also need to be discussed. Nurse-midwives are commonly confronted with ethical dilemmas.Citation31 In Africa, however, there has been little focus in education that produces professionals who are skilled at ethical problem-solving.Citation32 Counselling of adolescents with reproductive health problems seemed to cause ethical dilemmas for our respondents, suggesting that they were ill-prepared to deal with adolescent sexuality. Moreover, there was a tendency towards more youth-friendly attitudes among registered nurse-midwives and those who had undergone continuing education related to adolescent sexual and reproductive health. One helpful way to address attitudinal barriers could be for programme managers to encourage the development of critical thinking during undergraduate training and continuing education, focusing on the cultural and moral dimensions attached to adolescent sexuality. Critical thinking is a process of purposeful thinking, which has been widely used in the teaching of ethics.Citation33 Key features of this process involve examination of an ethical dilemma and critical analysis of personal beliefs and values related to this dilemma (e.g. through values clarification exercises), thus becoming aware of one's attitudes and biases and what impact they may have on, in this case, adolescents. Subsequently, new insights and perspectives might be achieved.Citation31Citation34 Besides self-assessment and reflection, which can be done with a partner or in a group, there are ways such as seeking information that is in opposition to one's own views that can facilitate the development of critical thinking.Citation31Citation35 Furthermore, cultivating a questioning attitude to what is presented as “proven fact” is of great importance in the development of open-mindedness. Moreover, nurse-midwives should be encouraged to think independently and to adopt non-judgmental and non-directive counselling practices. However, critical thinking cannot be developed or maintained in a vacuum.Citation31Citation35 Those in nursing and other leadership positions could also play an important role in encouraging wider social discussion of these matters. This would create an environment that is more tolerant of adolescent sexuality and that recognises the beneficial public health effect for adolescents of greater access to youth-friendly sexual and reproductive health services. | ||||

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the Swedish Research Council and the National Research School in Health Care Sciences for financial support. Thanks to all nurse-midwives who participated in the study, and to Dr. Zvinavashe and the late Ms. Mushinge, who participated during the pilot phase. We would also like to thank Prof. B Höjer and Prof. B Eriksson for their valuable comments.

Notes

* Enrolled nurse-midwives have two years of nursing training and one-year of midwifery training, and their professional role is restricted to clinical work. Registered nurse-midwives have three years of nursing training and one year of Midwifery Training, and their professional role includes administrative as well as clinical work.

* The word “promiscuity” is highly loaded in Kenya and Zambia, where a promiscuous person is believed to have many sexual partners and is thus considered a morally bad person. STIs are often associated with promiscuous behaviour and STI patients are commonly stigmatised at clinics.

* Common views about masturbation in both countries are that it is a sinful act, which can even be dangerous. For instance, those who masturbate are said to experience mental disorders or fertility problems.

* “Out-of-school” refers to a boy or a girl who has never attended school or who has interrupted their schooling.

References

- RW Blum, K Nelson-Mmari. The health of young people in a global context. Journal of Adolescent Health. 35: 2004; 402–418.

- United Nations Population Fund. State of the World Population. Investing in Adolescents' Health and Rights. 2003; UNFPA: New York.

- A Fedders, C Salvatori. Peoples and Cultures of Kenya. 1980; Trans Africa: Nairobi.

- VK Pillai, TR Barton. Modernization and teenage sexual activity in Zambia. Youth & Society. 29(3): 1998; 293–310.

- K Kiragu, LS Zabin. Contraceptive use among high school students in Kenya. International Family Planning Perspectives. 21: 1995; 108–113.

- TL Gall. Worldmark Encyclopedia of Culture and Daily Life. 1998; Eastword Publications Development: Cleveland.

- P Miller. The Lesser Evil. The Catholic church and the AIDS epidemic. 2001; Catholics for a Free Choice: Washington.

- B Carmody. Religious heritage and premarital sex in Zambia. Journal of Theology for Southern Africa. 115: 2003; 79–90.

- Central Bureau of Statistics. Kenya Demographic and Health Survey. Preliminary report. 2003; CBS: Nairobi.

- Central Statistical Office. Zambia Sexual Behaviour Survey. 2003; CSO: Lusaka.

- M Chatterji, N Murray, D London. The Factors Influencing Transactional Sex Among Young Men and Women in 12 Sub-Saharan African Countries. 2004; Policy Project for USAID: Washington DC.

- National Council for Population and Development. Adolescent and Reproductive Health Development Policy, Kenya. 2003; NCPD: Nairobi.

- World Health Organization. An assessment of the need for contraceptive introduction in Zambia. 1995; WHO: Geneva.

- BM Ahlberg, E Jylkäs, I Krantz. Gendered construction of sexual risks: implications for safer sex among young people in Kenya and Sweden. Reproductive Health Matters. 9(17): 2001; 26–36.

- KN Mmari, RJ Magnani. Does making clinic-based reproductive health services more youth-friendly increase service use by adolescents? Evidence from Lusaka, Zambia. Journal of Adolescent Health. 33: 2003; 259–270.

- W Koster-Oyekan. Why resort to illegal abortion in Zambia? Findings of a community-based study in Western province. Social Science & Medicine. 46(10): 1998; 1303–1312.

- M Okumu, I Chege. Female Adolescent Health and Sexuality in Kenyan Secondary Schools: A Report. 1994; African Medical Research Foundation: Nairobi.

- K Rogo. Induced abortion in Kenya. Paper for International Planned Parenthood Federation. 1993; Centre for the Study of Adolescence: Nairobi.

- Central Statistical Office. Zambia Demographic and Health Survey. Lusaka: CSO, 2001–2002.

- World Health Organization. Adolescent health and development in nursing and midwifery education. 2004; WHO: Geneva.

- J Liljestrand. Supporting midwifery. Issue paper. Health Division Document No. 2. 1998; SIDA: Stockholm.

- Deciding women's lives are worth saving: expanding the role of midlevel providers in safe abortion care. Ipas Issues in Abortion Care No.7, 2002.

- NW Muturi. Communication for HIV/AIDS prevention in Kenya: social-cultural considerations. Journal of Health Communication. 10: 2005; 77–98.

- P Ndubani, B Hojer. Traditional healers and the treatment of sexual transmitted illnesses in rural Zambia. Journal of Ethnopharmacology. 67(1): 1999; 15–25.

- ML Oindo. Contraception and sexuality among the youth in Kisumu, Kenya. African Health Sciences. 2(1): 2002; 33–40.

- Ndhlovu M. Nurses' experiences of abortion in South Africa and Zambia. Unpublished thesis, University of the Western Cape, South Africa, 1999.

- M Magadi, M Kuyoh. Abortion: attitudes of medical personnel in Nairobi. K Rogo. Unsafe Abortions in Kenya: Findings from Eight Studies. 1996; Population Council: Nairobi.

- R Jewkes, N Abrahams, Z Mvo. Why do nurses abuse patients? Reflections from South African obstetric services. Social Science & Medicine. 47: 1998; 1781–1795.

- K Rogo, S Orero, M Oguttu. Preventing unsafe abortion in Western Kenya: an innovative approach through physicians. Reproductive Health Matters. 6(11): 1998; 77–83.

- M Klingberg-Allvin, VV Tam, NT Nga. Ethics of justice and ethics of care. Values and attitudes among midwifery students on adolescent sexuality and abortion in Vietnam and their implications for midwifery education: a survey by questionnaire and interview. International Journal of Nursing Studies. 2006. Jan 12; [E-publication ahead of print].

- A Botes. Critical thinking by nurses on ethical issues like the termination of pregnancies. Curationis. 23(3): 2000; 26–31.

- S Haegert. An African ethic for nursing. Nursing Ethics. 7(6): 2000; 492–502.

- A Thompson. Bridging the gap: teaching ethics in midwifery practice. Journal of Midwifery and Women's Health. 49: 2004; 188–193.

- B Williams. Developing critical reaction for professional practice through problem-based learning. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 34(1): 2001; 27–34.

- B Kozier, G Erb, K Blair. Professional Nursing Practice. Concepts and Perspectives. 3rd ed, 1997; Addison-Wesley: New York, 236–237.