In this issue Schneider and colleaguesCitation1 point to some of the health system challenges for scaling up antiretroviral (ARV) therapy to the majority of the people living with HIV and AIDS (PLWHAs) who will need it over the coming years. They assume that in low-income countries financial resources and supplies of drugs do not constitute anymore the most important obstacles to widespread ARV use. Indeed many of the countries most affected by HIV now have steeply increased budgets available for AIDS care, either from their government budgets or from sources such as the Global Fund, PEPFAR and the World Bank. Despite funding being available, scaling up ARV therapy has been slower than hoped for. The WHO objective of treating three million people by the end of 2005 (“3 by 5”) has not been reached; instead, an estimated 1.6 million were put on ARVs.Citation2. Schneider et alCitation1 identify the need for reorientation of service delivery towards chronic disease care, insufficient supply of human resources for health and existing service delivery cultures as key constraints to scaling up. This seems a fair assessment of the situation in many countries of southern Africa.

Indeed the challenge is unprecedented. Health systems that were mainly set up to deliver maternal and child health services and care for acute episodes of disease suddenly have to cater for large numbers of PLWHAs, in need of lifelong chronic disease care. The closest analogy to ARV therapy in the health system in sub-Saharan Africa is tuberculosis (TB) care, but the usefulness of this comparison is limited. Strategies developed to assure treatment adherence over six months, such as direct observation by health workers in TB-DOTS, may not be very inspiring for assuring lifelong adherence. Indeed, only a few of the ARV delivery models documented build directly on the TB-DOTS experience. Instead, the process of ART as documented in pilot projects, as Schneider et alCitation1 explain, is often framed in patient-centred and rights-based discourses around patient empowerment and participation. Such an approach is invariably labour-intensive in skilled personnel. Whether such patient-centred approaches are feasible on a large scale in all of the countries hardest hit by HIV and AIDS, remains to be seen.

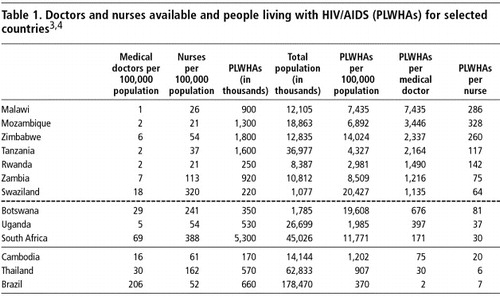

The challenges ahead differ between countries, as the data in Table 1 show. This table simply tabulates for a selection of countries the data published on WHO and UNAIDS websitesCitation3Citation4 on the availability of medical doctors and nurses against the number of PLWHAs in the country, and estimates the number of PLWHAs per medical doctor and per nurse. It is often estimated that some 20% of PLWHAs are presently in need of ARVs. However, after large-scale introduction of ARV therapy these cumulative numbers will grow rapidly, and ultimately all PLWHAs will end up needing ARVs.

It is striking to note that most countries praised for their performance in the ARV scale-up are among those with the lowest numbers of PLWHAs per doctor (below the dotted line in the Table). This is most obvious for Brazil, Thailand and Cambodia which have 2, 30 and 75 PLWHAs per doctor respectively. But also within sub-Saharan Africa there is wide variety. The numbers of PLWHAs per doctor are well below 1,000 and those per nurse well below 100 in South Africa, Uganda and Botswana. In other countries, these ratios are far higher. Malawi, Mozambique and Zimbabwe are the most extreme cases; they have more than ten times more PLWHAs per doctor than South Africa. They even have considerably more PLWHAs per qualified nurse than South Africa or Cambodia have PLWHAs per doctor.

Given these human resource constraints, there are theoretically two ways forward: 1) rapidly increasing the number of doctors and nurses available for service delivery; or 2) adopting ARV delivery models that need fewer doctors and nurses. The first option has received quite some attention lately,Citation5 the second considerably less. We will focus here on the issue of ARV delivery models.

Our contention is that ARV delivery models will have to be context-specific. The countries at the top of the table, with over 2,000 PLWHAs per doctor, may have to develop ARV delivery models that are quite different from Botswana or South Africa, and certainly from Brazil, with its two PLWHAs per doctor.

This challenge to health systems is unprecedented, but on the ground health services and communities are busy coping with it. It thus seems likely that creative solutions are being developed, probably not by academics, rather by field workers and local communities. As Schneider et alCitation1 describe, some pilot projects use patient-centred models, heavily relying on qualified personnel. But other projects are rapidly delegating most tasks to less qualified personnel, pushing standardisation and simplification as far as possible. Others may be relying more on new cadres, such as lay providers and expert patients.

Relatively little is reported about this grassroots reality. This may partly be because practical issues of health services organisation are often considered to be “local” and hence too context-bound to be of “scientific” interest. It may also be that some actors try to conceal the reality, to shield themselves from criticism. Indeed, these new realities are likely to challenge the medical and nursing professions' established modes of operating and their related monopolies. These actors may even have made technical “choices” – such as to forego laboratory monitoring of patients on ARVs – which may be judged as unacceptable by certain physicians' standards. But such approaches may well be the only feasible ones for the really significant ARV scale-up needed for the required impact. In high burden communities, mortality among young adults is so high that truly massive scaling up will be essential. Thus, there may be a balance to strike between the physician's traditional individualised perspective (What is best for the individual patient?) and the collective perspective (How can we stop this community's social degradation?).

Recently, some pilot projects in low-income countries have published the outcomes of their patient cohorts.Citation6Citation7 And the news is good: patients on ARVs are faring well, even in resource-poor countries, even PLWHAs who started ARV therapy late, with very low CD4 counts. Mortality among PLWHAs on ARVs in these pilot projects is around 10% in the first year, and much lower afterwards. This good news comes at a price: the caseload of patients on ARVs is likely to grow relentlessly, and far beyond the current estimates, which still consider that PLWHAs will only be on ARVs for an average of three years.Citation8 In the short term, the challenge was to put three million PLWHAs on ARVs by 2005. In the long term, the challenge may well become to maintain 10–15 million PLWHAs on long-term ARV therapy. To do so will require innovative approaches. There are simply no precedents on a similar scale in sub-Saharan Africa.

This prospect also points to the most important of all health systems challenges: how to substantially decrease new HIV infections in high prevalence countries. Despite some rhetoric on the treatment–prevention synergy, till now little hard evidence is available on how the opportunities created by ARVs can be used to intensify and harness HIV prevention. Only in a few of the high burden countries has HIV transmission substantially decreased. How this has happened remains controversial. Whether health systems will be able to cope with the growing numbers of PLWHAs on ARVs in the longer term will critically depend on decreased HIV transmission in the short term. In the current state of affairs, every new HIV infection will be in need of ARV therapy some ten years later, and will need to be maintained on ARVs for many years. Countries with a high burden of HIV and AIDS will need vastly strengthened health systems to do so, but the practical health service configurations able to cope with such a challenge still have to emerge.

References

- H Schneider, D Blaauw, L Gilson. Health systems and access to antiretroviral drugs for HIV in southern Africa: service delivery and human resources challenges. Reproductive Health Matters. 14(27): 2006; 12–23.

- World Health Organization. The 3 by 5 Initiative. At: <http://www.who.int/3by5/en/. >. Accessed 21 February 2006.

- World Health Organization. Global Atlas of the Health Workforce. At: <http://www.who.int/globalatlas/default.asp. >. Accessed 21 February 2006.

- UNAIDS. HIV data. At: <http://www.unaids.org/en/Regions_Countries/default.asp. >. Accessed 21 February 2006.

- L Chen, T Evans, S Anand. Human resources for health: overcoming the crisis. Lancet. 364: 2004; 1984–1990.

- P Severe, P Leger, M Charles. Antiretroviral therapy in a thousand patients with AIDS in Haiti. New England Journal of Medicine. 353: 2005; 2325–2334.

- D Coetzee, K Hildebrand, A Boulle. Outcomes after two years of providing antiretroviral treatment in Khayelitsha, South Africa. AIDS. 18: 2004; 887–895.

- JA Salomon, DR Hogan, J Stover. Integrating HIV prevention and treatment: from slogans to impact. Public Library of Science Medicine. 2: 2005; e16.