Résumé

The aim of this study was to examine the factors contributing to the increase in condom use among college students in Durban, KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa, and some of the barriers to consistent condom use. The data were drawn from six focus group discussions with male and female students aged 18–24 in three public tertiary education institutions, supplemented by a survey of 3,000 students aged 17–24. Condoms had become “part of sex” and highly acceptable to the great majority, and were easily accessible. They were primarily being used for preventing pregnancy; many students liked not having to go to a health facility for supplies. Less than half of male and only a third of female students thought male partners had greater influence over the decision whether a condom was used. If a woman requested condoms, men and women agreed the man must comply. Some men were suspicious of women who agreed to have unprotected sex. Almost 75% of sexually active students surveyed reported condom use at last sexual intercourse, but consistent condom use, reported by only a quarter, remains the main challenge. It may be more effective to promote condoms for contraception among sexually active young people than for HIV prevention. Condoms have become the most commonly used contraceptive method among students, and this trend should be reinforced.

Resumen

Une étude a examiné les facteurs de l’accroissement de l’utilisation des préservatifs chez des étudiants de Durban, KwaZulu-Natal, Afrique du Sud, et les obstacles à une utilisation suivie. Les données recueillies pendant six discussions avec des étudiants et des étudiantes de 18 à 24 ans dans trois institutions publiques d’enseignement supérieur ont été complétées par une enquête auprès de 3000 étudiants de 17 à 24 ans. Les préservatifs faisaient « partie de la sexualité », étaient bien acceptés par la grande majorité et faciles à trouver. Ils servaient principalement à éviter les grossesses ; de nombreux étudiants appréciaient de pouvoir les obtenir sans se rendre dans un centre de santé. Moins de la moitié des garçons et un tiers seulement des filles pensaient que les partenaires masculins influençaient davantage la décision d’utiliser ou non un préservatif. Si une fille demandait un préservatif, les garçons et les filles jugeaient que le garçon devait accepter. Certains garçons se méfiaient des femmes acceptant d’avoir des rapports non protégés. Près de 75% des étudiants sexuellement actifs ont indiqué qu’ils avaient utilisé un préservatif lors de leur dernier rapport, mais l’utilisation suivie de préservatifs, rapportée par seulement un quart, demeure le principal enjeu. Il peut être plus efficace de promouvoir les préservatifs pour la contraception que pour la prévention du VIH chez les jeunes sexuellement actifs. Les préservatifs sont devenus la méthode contraceptive la plus utilisée par les étudiants et cette tendance devrait être renforcée.

El objetivo de este estudio fue examinar los factores que contribuyen al aumento en el uso del condón entre los estudiantes universitarios en Durban, KwaZulu-Natal, Sudáfrica, así como algunos de los obstáculos al uso habitual del condón. Se recolectaron datos por medio de seis discusiones en grupos focales con estudiantes de sexo masculino y femenino, de 18 a 24 años de edad, en tres instituciones escolares públicas de tercer nivel, suplementados por una encuesta entre 3,000 estudiantes de 17 a 24 años. El condón, fácil de adquirir, había pasado a ser “parte del sexo” y muy aceptado por la gran mayoría. Se utilizaba principalmente para la prevención del embarazo; a muchos de los estudiantes les gustaba el no tener que acudir a un servicio de salud para obtener suministros. Menos de la mitad de los hombres y sólo una tercera parte de las mujeres pensaban que las parejas de sexo masculino tienen mayor influencia sobre la decisión de usar un condón. Ambos sexos convinieron en que, si una mujer solicita el uso del condón, el hombre debe acceder. Algunos hombres sospechaban de las mujeres que aceptan tener relaciones sexuales sin protección. Casi el 75% de los estudiantes sexualmente activos encuestados informaron haber usado un condón en su última relación sexual, pero el uso habitual del condón, practicado por sólo una cuarta parte, continúa siendo el gran reto. Quizás sea más eficaz promover este método para la anticoncepción entre los jóvenes sexualmente activos que para la prevención del VIH. Dado que es el anticonceptivo más comúnmente usado entre los estudiantes, esta tendencia debe reforzarse.

The level of unwanted pregnancy and HIV infection among young people in South Africa is a matter of grave concern. Teenage pregnancy is relatively common, with more than one third of women having a child before the age of 20. Nearly all these pregnancies are unplanned, and most are unwanted.Citation1 At the same time, HIV prevalence among young people is relatively high: 10% among 15-24 year olds according to a recent national survey.Citation2 The highest incidence of HIV infections occurs among young people, who account for some 60% of new infections.Citation3 In this context, the promotion of condoms is a top public health priority.Citation4 The male condom is the only widely used device that offers dual protection against pregnancy and disease; when used correctly and consistently, it is highly effective at preventing pregnancy and HIV infection.Citation5Citation6

A number of earlier studies have reported relatively low condom use among young people in South Africa.Citation1, Citation3, Citation7 In a 1995 survey of young people in three communities, only 38% of boys and 21% of girls had ever used a condom.Citation7 In addition, the South African Demographic and Health Survey 1998 found that condom use among 15–19 year-old girls was 19.5%.Citation1 Yet most studies in South Africa report that young people are aware of condoms, especially their value in preventing HIV infection.Citation8 Citation9 Citation10 A 1999 study among young people in a township in South Africa found that young women in particular encountered social pressure against carrying condoms. They felt their reputations were tainted by gossip; male participants confirmed that they did not trust women who carried condoms.Citation10

Today, however, a growing body of evidence points to an increase in condom use among young people in South Africa. Several recent large-scale surveys have found that more than 50% of young people used condoms at last sexual intercourse.Citation2, Citation11 Education has been positively associated with increased frequency of condom use,Citation12 and condom use is higher among youth in school than those out of school.Citation11 Some studies have found that young people aged 15–19 were more likely than those aged 20–24 to use condoms.Citation1 Among university students younger age was associated with greater confidence to wear a condom, “carry a condom and suggest using a condom.Citation13 However, in 1999 Rutenberg et al found no association with age between sexually active 14–15 years olds and 20–22 year olds.Citation11

Consistent use remains elusive, however; in a community survey of young people aged 12–24 in 2000, only one-third of young men and women who were sexually active reported that they had consistently used condoms during the last five acts of intercourse.Citation14

The aim of this study was to examine in depth the factors that underlie the rising use of condoms among students at three public tertiary institutionsFootnote* in Durban, South Africa, and identify the barriers to consistent use. Particular attention is given to the relative importance of pregnancy prevention and disease prevention as motives for condom use, the role of gender in condom negotiation and the circumstances and relationships that mitigate against use. Students are, of course, an elite group. Only about 8% of South Africans have a tertiary education.Citation15 Though far from typical of young people, however, they are of special importance for the future of the country and lessons can be learnt from this group that may have relevance to the wider population of young people.

Methods and participants

The qualitative data come from six focus group discussions (FGDs) held in February and March 2003. Two were mixed sex groups, two were men only and two were women only. Each FGD consisted of six to eight participants. The groups were racially mixed in order to obtain a range of perspectives, but the majority of participants were Black. Their ages ranged from 18 to 24 years. In the first instance, posters were placed around the campus inviting participation, but this attracted few participants. As a result, students were approached directly after lectures and invited to participate. Participants were selected on the basis of race to reflect the demographic profile of the province. All participants were assured of confidentiality and that anonymity would be maintained at all times. At each session, one moderator and one note-taker were present. Both the moderators and note-takers had prior experience in FGDs, and received one day’s intensive training. The venue, in most cases a small lecture room, was conveniently located for participants and ensured maximum privacy. A discussion guide was used, but at times additional topics were explored for clarification. The guide covered acceptability of condoms, consistency of condom use, condom negotiation, condom symbolism and the implications of condom use. Discussions were in English and lasted 2–3 hours on average. All sessions were tape-recorded, transcribed and analysed using Ethnograph. The data were organised according to particular themes and assigned preliminary codes. In the final analysis, the codes were modified and recurrent themes that emerged across transcripts were identified.

The quantitative data were obtained from self-completed questionnaires administered between April and May 2003 at the same public tertiary institutions. It covered young people’s perception of risk of HIV/AIDS and pregnancy, attitudes towards condoms, beliefs about condom use practices, perceptions of condom use by peers and consistency of use. Permission was first obtained from the institutions to conduct the survey, which was piloted with 25 men and 25 women and revised. The questionnaire was distributed at the end of lectures, with permission of the lecturers, for self-completion. Respondents were briefed about the purpose of the research and asked if they would be willing to participate. All respondents were assured of confidentiality and anonymity. They were asked to put the questionnaire in the envelope provided and hand it back to the researcher. The response rate was approximately 80%. The questionnaire took about 15–20 minutes to complete. Time constraints were cited as the main reason for non-participation. The data were analysed using SPSS. Descriptive analysis was conducted to identify differences between men and women in condom attitudes and use, which are summarised in tabular form, with application of chi-square tests to determine statistical significance. Ethical approval was obtained from the University of KwaZulu-Natal.

The survey sample consisted of 3,000 college students, 43% men and 57% women, who were almost equally divided between the three institutions. An attempt was made to ensure that students from different faculties were included, including science and engineering, humanities and social science. Most (75%) were Black; 17% were Indian, 6% White and 2% Coloured. Their ages ranged from 17 to 24 years. Most (87%) were not currently employed, while 3% were employed full-time and 10% part-time. The majority (94%) had never been married, but 70% had ever had sexual intercourse. The median age at first sexual intercourse was 15 for men and 17 for women. The median number of lifetime partners for men was six and for women two.

Results

Condom acceptability

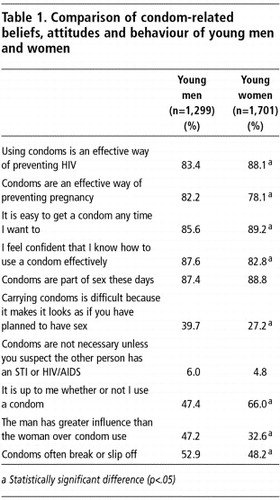

Overall, condoms were well known and a highly popular method with the majority of survey participants, more than 75% of whom were aware of the dual protective benefits of condoms against pregnancy and HIV infection, as shown in Table 1. Almost 87% of men and 89% of women in the survey felt that condoms were part of sex these days, and the FGDs supported these findings. For most sexually active participants in the FGDs, condoms were seen as a natural part of sexual relationships and sex without a condom as far too dangerous.

“Condoms have become more like an institution now. This is mainly because we are constantly being bombarded with messages that say that you have to use a condom if you are going to have sex.” (Women-only FGD)

Nearly 86% of men and 89% of women reported in the survey that it was easy to get a condom any time they wanted. At all three campuses, condoms were available either from vending machines or free supplies in toilets and health facilities. In general, the focus group discussants considered condoms as convenient and easily accessible. Many liked the fact that they did not have to go to a health facility to obtain supplies and could obtain a condom over the counter without a prescription. Most said they would prefer to purchase condoms, even though they are relatively expensive, than to obtain them free of charge from a health facility. In the FGDs, the only problems of access related to vacation time when many students returned to their rural homes.

In the FGDs comparison of condoms with alternative methods of contraception, particularly the pill, tended to favour condoms. Hormonal methods were associated with weight gain, moodiness, loss of sexual drive and infertility.

“The condom is much easier than taking the pill. With the pill you have to remember to use it everyday. If you forget to take it there is the risk of falling pregnant.” (Women-only FGD)

“I actually think a lot of guys are more willing to use condoms than have their girlfriends go onto the pill, at least among my friends.” (Women-only FGD)

However, in all the FGDs men and women had some complaints about condoms. They argued that sex with a condom was not very enjoyable because it interrupted the spontaneity. Despite this, they felt it was important to use condoms and would rather use condoms than jeopardise their future.

“When I think of condoms, I usually think of pregnancy and disease, but it reduces sensation during sexual intercourse.” (Mixed sex FGD)

“It is not that I like to use the condom. Condoms take away sexual pleasure but also if you do not use it you know that you may fall pregnant and you then have to bear the consequences.” (Women-only FGD)

In the survey, respondents were asked how worried they were about becoming infected with HIV and about unintentional pregnancy. For the sexually active women, the risk of pregnancy was equal to the risk of HIV infection; 70% said that they were quite, very or extremely worried about both. For sexually active men, concern about HIV infection was greater than concern about pregnancy (71% versus 56%). This gender difference was also found in the FGDs. Pregnancy was still viewed as the woman’s responsibility and many young women felt that men can easily abdicate responsibility by refusing to acknowledge paternity of the child:

“Boys do not have to take responsibility for the baby. They do not think about the implications for the woman. An unwanted pregnancy often means the end of the girl’s education. The end of everything!” (Mixed sex FGD)

About half of both men and women in the survey reported that condoms may slip or break (Table 1). Both men and women in the FGDs also voiced concern that sometimes condoms slipped or broke. Women stressed the importance of using condoms in conjunction with another highly effective method of contraception in order to prevent unwanted pregnancy, but most acknowledged that this was not very common and that most women relied on one method.

“Sometimes you may be using a condom but it may break. You may walk out of the room thinking you are protected and then find out a few months later that you are pregnant and your boyfriend does not want to take responsibility because he was using a condom.” (Women-only FGD)

The condom was primarily being used as a method of preventing pregnancy. Few men or women associate condoms with the suspicion of their partner being infected with an STI or HIV. In the survey, only about 5% endorsed the proposition that “condoms are not necessary unless you suspect the other person has an STI or HIV/AIDS” (Table 1). This does not mean they did not recognise the risk of HIV infection. In the FGDs, young people were aware that they might be at risk of HIV infection because of multiple sexual partners and frequent sexual partner change:

“Young people are often at risk of AIDS because they usually do not have a long-term partner. They tend to change partners quite often and they also tend to have more sexual partners.” (Men-only FGD)

Condom negotiation

In the survey, less than half of men and a third of women (47% versus 33%) felt that the man has greater influence than the woman over whether or not a condom is used. However, women were more likely than men to state that it is up to them whether or not to use a condom during intercourse (66% versus 47%). In the FGDs, young people explained that women had greater control over the use of condoms in relationships where there was greater equality. Often the man was forced to use a condom if he wanted to have intercourse with his partner.

“I personally think that if a woman told a man to use a condom the man will do exactly as she wants.” (Men-only FGD)

The women felt they had greater control over their sexual urges than men. Many of the men agreed that they were sometimes willing to do anything to have sex or if they were in love. However, many of the women argued that men were more likely to have greater control over condom use in abusive relationships.

“Women often have more control over the relationship because they can tantalise men and persuade them to do whatever they want. However, it depends on the power relations and also, on the personality of the man. For example, if the male partner is violent the woman is less likely to assert her preferences.” (Women-only FGD)

“It depends on the personality of the man. Some men are quite aggressive and if the woman wants to use a condom he might say ‘screw you’ and have sex with her anyway but a more passive man will think twice about his actions.” (Men-only FGD)

As relationships developed over a period of weeks or months, FGD participants reported, couples usually discussed condoms. Communication, they said, was important to ensure that consensus was reached about the need for condoms. In general, both men and women reported that condoms were more likely to be used in the longer term if they had been used from the start of a relationship.

In casual relationships, men said they usually used condoms without explicit prior agreement from the partner. However, it was not uncommon for women to carry condoms with them. Indeed the survey evidence suggests that men experienced more difficulty than women (40% versus 27%) in carrying condoms because it implied that sex had been planned. Sometimes, according to the FGDs, if the man does not initiate condom use the woman will say something like: “Do you have anything with you?” However, men admitted that there was a double standard about women carrying condoms, and that it was still more acceptable for men to introduce condom use in a relationship. They felt they should introduce condoms themselves.

“There is a double standard when it comes to girls and boys. However, it is not something we talk about. If a girl carries a condom she is seen as a slut.” (Men-only FGD)

“I think it is important for the girl to follow the correct protocol. If it is the first time and the girl makes the move I get worried. I feel like she is moving too fast for me.” (Mixed sex FGD)

However, a few men had adopted the opposite perspective and felt quite negative about women who agreed to have sex without a condom, whom they saw as untrustworthy and irresponsible.

“If a girl allows me to have sex with her without the condom the first time I guess I already have formed a picture of her. I feel I cannot trust her because she has no idea with whom I have been, yet she is willing to have sex with me without a condom.” (Mixed sex FGD)

Condom use

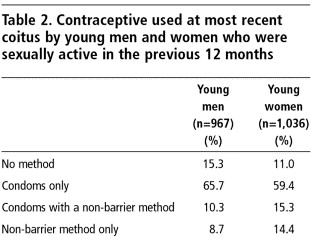

The survey found that condom use was high among sexually active young men and women in the previous 12 months (Table 2). Almost 75% reported using condoms at last sex either alone or in combination with another method, with a minority of men (10%) and women (15%) reporting condom use in conjunction with another contraceptive method. The use of a non-barrier method by itself was higher among women (14%) than men (9%). Evidence from the FGDs suggests that use of non-barrier methods, mainly pills and injections, was largely confined to longer-term relationships.

The majority of young men and women in the survey felt confident that they knew how to use a condom effectively, though no demonstration was asked for. However, only 87% of men and 90% of women surveyed who reported using a condom at last sexual intercourse said that the condom was put on before penetration. In addition, 28% of men and 32% of women who reported using the condom before penetration also reported that some genital contact had occurred before the condom was used, increasing the risk of sexually transmitted infections. In the FGDs, men said they found it difficult to use condoms once any form of penetration had occurred.

“I usually put on the condom before I penetrate my partner because I am afraid I am not able to withdraw once penetration has occurred. However, sometimes partial penetration occurs and then you realise what you are doing and you put on a condom before you fully penetrate.” (Men-only FGD)

Condom use was also not consistent in all sexual encounters. In the survey, respondents were asked to rank consistency of use on a scale from 0 (never) to 10 (always). Only 24% of men and 28% of women classified themselves as always using condoms. As a partial check on the validity of reported condom use, we assessed its relationship to reporting of any sexually transmitted infection, controlling for number of lifetime partners. Compared with consistent users, inconsistent or non-users were two times more likely to report an infection (odds ratio 2.44; 95% confidence intervals 1.77 to 3.38). In the FGDs, a number of reasons for inconsistent condom use emerged. Some men and women reported not using condoms during first sex with a new partner. Often this was because they did not expect to have intercourse and were not prepared, or they did not want to destroy the romantic atmosphere by introducing a condom. In these situations there was greater concern about pregnancy rather than HIV infection. As a result, some women reported using emergency contraception.

In the FGDs men said they only carried condoms when they expected to have sex, whereas in casual relationships it is usually not planned. Otherwise, carrying condoms makes it look as if sex is contrived. Some men also admitted that they did not refuse sex if they did not have a condom. Both men and women in the FGDs pointed out that in the heat of passion or after the consumption of alcohol they might forget about condoms. Yet another reason for non-use of condoms, familiar from other research, was the belief that one can discern a person’s HIV status from his or her physical appearance.

Both men and women in the FGDs felt that in regular sexual relationships there was more concern about pregnancy but in short-term relationships there was more concern about infection. Men and women who perceived a high risk of pregnancy were more likely to use a contraceptive method. If they were not using contraception and were worried about pregnancy they were much more likely to use condoms consistently to protect against that risk. However, if they were using another method of contraception, both men and women said condoms were not used consistently.

Discussion

As with nearly all studies of sexual behaviour, the value of this study depends on the veracity of reported behaviour. The survey was in the form of an anonymous questionnaire, which hopefully encouraged accurate disclosure of behaviour. However, our main reason for confidence in the results is the high level of consistency between the findings of the survey and the FGDs and a similar consistency in the reporting of men and women. In addition, reported inconsistent or non-use of a condom was found to be strongly associated with experience of a sexually transmitted infection.

About three-quarters of both men and women in the survey reported condom use at most recent coitus, a level of protection that compares favourably with estimates from more developed countries.Citation16 An additional 10% used a non-barrier method of contraception; thus, the proportion protected against unintended pregnancy was about 85%. Condom use was sufficiently high, in our view, to justify the claim that condom use has become the norm and a routine part of the sexual culture among Durban students. This is further supported by another large scale survey conducted in the province of KwaZulu-Natal which demonstrated high levels of awareness and condom use among young people more generally.Citation17

Several factors have contributed to the high acceptability and uptake of condoms among students. First, pregnancy avoidance is a top priority, particularly for women, for whom pregnancy spells disaster for progress through college and hopes of a well-paid job. While abortion is now legal in South Africa, it is still heavily stigmatised and therefore not to be undertaken lightly. The need to avoid pregnancy may indeed set students apart from out-of-school young women for whom motherhood may carry fewer penalties and which may even be welcomed as a step towards adult status.Citation18 However, attitudes towards pre-marital childbearing may be hardening. The 1998 South Africa Demographic and Health Survey records an appreciable decline in teenage fertility and only 20% of recent births to adolescents were reported as “wanted”.Citation1 In the KwaZulu-Natal Transitions to Adulthood Study, three-quarters of young men and women reported that a pregnancy in the next few weeks would be a big problem.Citation12

Secondly, non-barrier contraception is unpopular because of fears of side effects and unwarranted but common fears that future childbearing might be jeopardised by use of hormonal methods.Citation19Citation20 Moreover, condom use can be justified in terms of pregnancy avoidance even in relationships where fear of HIV infection is a major consideration. It needs no research to assert that negotiation of condoms for family planning is much easier than negotiation to avoid disease because it carries no imputation of distrust.

The results of this study challenge findings from other studies that men mostly dominate decisions about whether or not to use a condom.Citation21Citation22 Notably more women than men in the survey agreed with the proposition that “It is up to me whether or not I use a condom” and only 33% of women accepted that “The man has greater influence than the woman over condom use”. The qualitative evidence supports the survey data. The men acknowledged that if a woman requests condoms, they must comply. Indeed, some men were suspicious of women who agreed to have unprotected sex, and both men and women in the FGDs agreed that men’s domination persisted only in coercive relationships.

Many studies in Africa and elsewhere have shown that maintaining condom use in stable, committed relationships is particularly difficult.Citation23 Citation24 Citation25 Citation26 Our evidence is more nuanced. In longer-term relationships, rightly or wrongly, concerns about disease prevention disappeared but the need to avoid pregnancy typically remained strong. Some participants in the FGDs accepted that a shift from condoms to oral contraceptives, or perhaps injectables, was inevitable in stable relationships. Others claimed that condom use in stable relationships was more feasible than in transient affairs because sex could be anticipated with condoms available. The point was also made that if condoms were used at the start of the relationship, they became a habit that was relatively easy to maintain.

Despite the high levels of condom use in this population, however, consistent use remained elusive. In the survey only 24% of sexually active men and 28% of women claimed use in all coital acts. The FDGs provide some insights into the reasons, including unanticipated opportunities for intercourse, romantic intensity overcoming caution, sexual insecurity at the start of a relationship, alcohol use, use of a non-barrier method of contraception and occasional lapses in a long-term relationship. These are all understandable and possibly unavoidable reasons for departures from 100% protection with condoms. However, the common failure to attain this ideal must not be allowed to belittle the contribution of condoms to HIV control. Every sexual act that is protected by a condom reduces the risk of infection and unwanted pregnancy.

In conclusion, pregnancy prevention and HIV control should not be considered as separate domains of interest. On the contrary, it may prove more effective to promote condoms for contraceptive purposes among sexually active young people than for HIV control. Condoms have become the most commonly used contraceptive method among single women throughout sub-Saharan Africa,Citation27 and this trend should be reinforced.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all those who participated in and assisted with the study and the Mellon Foundation for funding the study.

Notes

* Two of these institutions were in the process of merging when the study was done.

References

- South African Demographic and Health Survey 1998. 1999; South African Medical Research Council and Macro International: Pretoria, Calverton MD.

- O Shisana, T Rehle, LC Simbayi. South African National HIV Prevalence, HIV Incidence, Behaviour and Communication Survey, 2005. 2005; Human Science Research Council: Cape Town.

- Lovelife. The Impending Catastrophe: A Resource Book on the Emerging HIV/AIDS Epidemic in South Africa. 2000; Love Life and Henry J Kaiser Family Foundation: Johannesburg.

- L Myer, C Morroni, C Mathew. Dual method use in South Africa. International Family Planning Perspectives. 28: 2002; 119–121.

- W Cates. The NIH condom report: the glass is 90% full. Family Planning Perspectives. 33(5): 2001; 231–233.

- World Health Organization. Joint WHO/UNAIDS/UNFPA policy statement: dual protection against unwanted pregnancy and sexually transmitted infections, including HIV. 2000; WHO: Geneva.

- L Richter. A Survey of Reproductive Health Issues among Urban Black Youth in South Africa. 1996; Society for Family Health: Pretoria.

- CG Hartell. HIV/AIDS in South Africa: a review of sexual behaviour among adolescents. Adolescence. 40(157): 2005; 171–181.

- A Harrison, N Xaba, P Kunene. Understanding safe sex: gender narratives of HIV and pregnancy prevention by rural South African school-going youth. Reproductive Health Matters. 5(9): 2001; 63–71.

- C MacPhail, C Campbell. “I think condoms are good but, aai, I hate those things”: condom use among adolescents and young people in a Southern African township. Social Science and Medicine. 52(11): 2001; 1613–1627.

- M Rutenberg, C Kehus-Alons, L Brown. Transitions to adulthood in the context of AIDS in South Africa: report of Wave I. 2001; Population Council: New York.

- N Rutenberg, C Kaufman, K Macintyre. Pregnant or positive: adolescent childbearing and HIV risk in KwaZulu Natal, South Africa. Reproductive Health Matters. 11(22): 2003; 122–133.

- K Peltzer. Factors affecting condom use among South African university students. East African Medical Journal. 77(1): 2000; 46–52.

- A Erulkar, M Beksinska, Q Cebekhulu. An assessment of youth centres in South Africa. 2001; Population Council: Nairobi.

- International Education Association of South Africa. Study South Africa: The Guide to South African Tertiary Education. 4th ed., 2004; IEASA: Durban.

- Gardner R, Blackburn R, Upadhyay U. Closing the condom gap. Population Reports H. 1999.

- P Maharaj. Reasons for condom use among young people in KwaZulu-Natal: Prevention of HIV, pregnancy or both. International Family Planning Perspective. 32(1): 2006; 28–34.

- E Preston-Whyte, M Zondi. African teenage pregnancy: whose problem?. S Burman, E Preston-Whyte. Questionable Issue: Illegitimacy in South Africa. 1992; Oxford University Press: Cape Town.

- S Castle. Factors influencing young Malians’ reluctance to use hormonal contraceptives. Studies in Family Planning. 34(3): 2003; 186–199.

- P Feldman-Savelsberg. Plundered kitchens and empty wombs: fear of infertility in the Cameroonian grasslands. Social Science and Medicine. 39(4): 1994; 463–474.

- C Varga. Sexual decision making and negotiations in the midst of AIDS: youth in KwaZulu Natal. Health Transition Review. 7(2): 1997; 13–40.

- A Blanc, B Wolff. Gender and decision-making over condom use in two districts in Uganda. African Journal of Reproductive Health. 5(3): 2001; 15–28.

- P Maharaj, J Cleland. Condom use with marital and cohabiting partnerships. Studies in Family Planning. 35(2): 2004; 116–124.

- J Adetunji, D Meekers. Consistency of condom use in the context of AIDS in Zimbabwe. Journal of Biosocial Science. 33: 2001; 121–138.

- M Ali, J Cleland, I Shah. Condom use within marriage: a neglected HIV intervention. Bulletin of World Health Organization. 82: 2004; 180–186.

- R Van Rossem, D Meekers, Z Akinyemi. Consistent condom use with different types of partners: evidence from two Nigerian surveys. AIDS Education and Prevention. 13: 2001; 252–267.

- Zildar VM, Gardner R, Rustein SO, et al. New Survey Findings: The Reproductive Revolution Continues. Population Reports 2003;Series M, No.17.