The slogan that could defeat the HIV epidemic is “No condom – No sex”, but who champions the condom? There is highly-funded international research for the development of antiretroviral drugs and vaccines against HIV, and even microbicides, but condoms have no well-funded champion anywhere, not even a full-time person at UNAIDS.

The theme of this journal issue is intended to be provocative. It is a response to the powerful anti-public health campaign against sexual and reproductive rights, led by right-wing religious leaders George W Bush and Pope Benedict XVI, whose policies demonise most sexual relationships – and have made condoms the symbol of them. It is important to challenge these sexual politics, as they threaten to undermine all the gains made in promoting safer sex and turning the HIV epidemic around.

Sex is the crux of the matter – who has it, with whom, how early in life and with what access to the means of making it safe. From a public health point of view, it does not and cannot matter who has sex or with whom, or at what age. Rather, what matters is recognising that almost everyone is going to have sex at some point, and ensuring that when they do, it is by their own choice, and that they have the means, the know-how and the ability to negotiate safe sex with their partner.

When it comes to messages about sex, people should be divided into those who want to have sex and those who do not want to have sex. Not having sex, of course, is safe, and by all means, let’s promote it. But on what basis? There are many people in the world who don’t like sex very much, but who feel pressured to have it (by partners, by friends) or feel they would be seen to be inadequate if they don’t have it. They would benefit from support for not having sex, or for putting it off until they feel differently about it. But how should supportive messages be phrased? “Abstinence” is a misnomer. It has sacrificial and religious overtones, it is about holding back, not giving in to temptation, not sinning. It has anti-sex connotations; it’s not just about not having sex. That is the crux of why abstinence-only programmes don’t work for very long, if at all. They are being preached to a lot of people who actually want to have sex, now, next week or as soon as someone interesting comes along. For those who do not want to have sex, here are some slogans:

If you don’t want sex, that’s cool, don’t have it!

If you don’t want sex, say so – and say no.

These slogans don’t carry the same message as “abstain from sex”, and they are relevant to more than just young, single people. There are people of all ages, including married and formerly married people who would rather not have sex either – and I don’t just mean women.

For those who do want to have sex, instead of asking them to twist themselves in knots and making them feel bad about it, which traditionalist religion and worried parents are very good at doing, how about a different sexual politics: one that is sex-positive, with safer sex messages that promote sexual health and well-being.

“Abstinence” no!

What exactly is “abstinence”? Does it mean only “not having sexual intercourse”? Or does it mean not kissing as well? What about touching, and bodies touching? Kissing and touching are both safe sexual practices, and they were practised very widely by my generation to excellent effect in our youth. We were pre-HIV but we did not have access to contraception before marriage and feared pregnancy and wanted to experiment with sex more than anything. (There were condoms, of course, but they were not for good girls and boys).

Kissing and touching are not, I suspect, considered to be “abstinence”, not only because they are part of the slippery slope to sexual intercourse, but because they admit that people have sexual feelings and want to express them. So “abstinence” must mean not having sex even if you want to, and if possible forcing yourself not to have sexual feelings at all, presumably so that you won’t be hankering after it all the time. Adolescents not experiencing sexual desires? That is a contradiction in terms. And it is very different from not being ready to have sex with another person. My mother taught me not to have sex before marriage but she also told me to come to her first if I needed an abortion. Why should young people today be any different? From a public health point of view, the prescription of “abstinence” is a potential death sentence for anyone who wants to have sex if the means to make it safe, at whatever age, are withheld.

Promoting “abstinence” is about promoting virginity and purity. The sexual politics of Mr Bush and the Pope follow a line that goes something like this: “If you choose sex (sin), you will be punished, and you will deserve it, but we will forgive you and try to alleviate your suffering, which hopefully you will have learned from.” Thus, Bush refuses to fund provision of safe abortions, but he will fund post-abortion care for treatment of the life-threatening complications of unsafe abortion. Similarly, he will not fund HIV prevention work that teaches young people how to have safer sex, or gives them the means to do so, but he will fund antiretroviral treatment for those who get HIV infection. (Of course, using billions of US dollars to buy antiretrovirals for Africa from the US pharmaceutical industry instead of generic producers may be another motivation, as well as competing with the Global Fund against HIV, TB and Malaria for influence.) And if you’re wondering why Bush still funds contraception at home and abroad, look at what is happening in the US right now, where legislation is pending in a number of states to support the “right” of pharmacists not to provide contraception and emergency contraception,Citation1 to see the impending future on this topic.

Lastly, a word about an odd term that is making an appearance in some of the abstinence literature, that is, promoting “secondary abstinence”. Its meaning seems to be a kind of second-chance offer to those (young people, again) who have strayed from the path of righteousness and can still save themselves if they stop now. But wait a minute. It has always been possible to have sex and then stop for a while, or for a long time, and not feel you have to go on having sex forever once you’ve started. It isn’t something people can’t control – even men. Again, the question is: what do you want? So can those wanting to promote a sex-positive sexual politics please eschew this language?

Abstinence-only campaigns do not emanate only from the sexual politics of two white men, however. They are also a problem of African governments who, having been flooded with US PEPFAR money, have handed over responsibility for HIV prevention work to Catholic and other Christian organisations whose health care services they are already often dependent upon. As Gill Gordon and Vincent Mwale say in their paper in this RHM issue:

“Faith-based organisations have always struggled with how to marry their moral mission and the need to protect health and life, given the reality of people’s sexual lives.”

In the past, however, faith-based groups took upon themselves the unambiguous role for good of providing care and support for people living with HIV and AIDS and their families, and have been doing a tremendous job of it. Now, however, tempted as venally as everyone else by Bush’s prevention dollars, many (though thankfully not all) have also taken on abstinence-only education and are disguising it as HIV prevention. Bush’s money made it easy for them – it exempted them from promoting comprehensive life skills, sexuality and relationships education by requiring them to promote abstinence before marriage and faithfulness after it. When the HIV incidence and prevalence figures start going up around them, however, especially among the young people who they are supposed to be “saving”, they will be forced to confront their own complicity and it will not be easy. Meanwhile, the failure of governments and other NGOs to ensure the provision of comprehensive sexuality education and condoms deserves only condemnation.

The evidence from the United States is that abstinence-only curricula have failed to demonstrate efficacy in delaying initiation of sexual intercourse.Citation2Citation3 This evidence is falling on deaf ears among those whose aim is the promotion of the morality of virginity, however, because for them the public health evidence is not the point.

The problem for the rest of us is what to do about the growing hegemony of abstinence-only campaigns. PEPFAR funding for antiretroviral treatment is prolonging thousands of lives in the countries that have accepted it. Without it, a lot more people would be dying. As happened with the Bush Global Gag Rule taking money away from safe abortion services, most organisations swallowed their principles and took the money. Bush’s philosophy “Bomb them or buy them” seems to be effective. Thus, the only solution is for other money and a sex-positive sexual politics to step into the breach and re-occupy public space. It is only when those who are sexually active stop believing that really “abstinence is better” and start believing that sex is good and even better when it is safe, that public health needs might prevail.

Condoms, yes!

Condoms do not equal safe sex, because sex does not equal intercourse, but without condoms, vaginal, anal and oral intercourse are not protected from STIs or HIV. I never thought it would be necessary to say something this obvious 25 years into the HIV epidemic, but there it is. Here are the facts about condoms: the evidence is that consistent condom use is highly effective. For example, a meta-analysis of 12 studies found that among participants who reported always using condoms, the summary estimate of HIV/AIDS incidence was 0.9 seroconversions per 100 person years (or less than one person per 100 per year). While among those who reported never using condoms in seven studies, the summary estimate of HIV/AIDS incidence was 6.7 seroconversions per 100 person years (or 6.7 people infected per 100 per year).Citation4 In other words, for those who are going to have sex, always using condoms is seven times safer against HIV than never using them, every time they have intercourse. No one ever claimed condoms were perfect. But they are the best there is and the best there will be for a long time coming.

Do condoms have holes in them? No. Unless you put them in the microwave or stick a pin through them. They are tested and re-tested to ensure their impermeability and durability. So why do the abstinence-only people feel they not only have the right not to promote condoms, but that they can also tell downright lies about them, such as that they have holes and don’t work well enough to bother using them. Such lies are immoral and unethical. And while it is wonderful that periodically a Catholic bishop, such as Tiny Muskens from the Netherlands while on a visit to Uganda, comes out in support of condom use,Citation5 these lone voices are being drowned out by thousands of others who are afraid to contradict the church – or lose their PEPFAR money.

The abstinence-only people go around saying that if condoms work so well, why is the HIV epidemic still growing? That’s a good question. The bad news is that not enough people who are at risk of HIV are using condoms at all, or using them all the time, and there’s a lot of work needed ahead to get them to do so. We humans just don’t change our entrenched behaviours overnight, no matter how much they put us at risk, and unsafe sex is an entrenched behaviour. The good news, though, is that condom use has been increasing steadily for many years now. Some of the people most at risk through frequent exposure, i.e. men who have sex with men and sex workers, began the upward trend of using condoms, and data now show increasing use of condoms among young single people as well. Not just in the rich countries but all across Africa as well. Cleland, Ali and Shah in this journal issue show from Demographic and Health Survey data that there was a large median increase of 1.4 percentage points per year in condom use by single young women (primarily for pregnancy prevention) in 18 sub-Saharan African countries from 1993 to 2001, and the trend is upward. This is the same sort of pace at which contraception was adopted as well.Citation6 They therefore say:

“Condom promotion in Africa has been, therefore, a success for single women. Its promotion for pregnancy prevention offers even greater potential [than for HIV prevention], as pregnancy prevention is the main or partial motive of most single women who use condoms.”

However, as Alice Welbourn says in her paper in this issue:

“For HIV positive women and girls, using a condom is more than protection against pregnancy, but a matter of life and death greater than the risks pregnancy can bring.”

And while it is true that the same increase in condom use has not been seen in married people, it must be also said that few public health campaigns have promoted condoms to stable and married couples since the epidemic began (the Caribbean being a notable exception). Social acceptance of the need for condom use in marriage has been glaringly absent, including among many of the people whose work is in HIV prevention. Yet a qualitative study by Nancy Williamson et al in this issue, among 39 married couples in Uganda who used condoms consistently, shows that it is feasible. Here’s how:

“Women used insistence, refusal to have sex, persuasion and deflection of distrust (e.g. suggesting condoms for family planning or to protect children) to get their partner to agree. Some men resisted but their reactions were often more positive than expected. Men’s reasons for accepting condoms were to please their partner, protect her from HIV, protect their children, protect themselves and, in some cases, continue having other partners.”

The vexed issues of trust and rights

One of the main reasons why promotion of condoms has been considered a problem is the issue of trust between partners. The concept of deflecting accusations of mistrust by asking to use condoms as a contraceptive method is one that heterosexual partners of both sexes should consider using, as it seems to work well.

Moreover, as several papers in this issue show, as condom use becomes socially acceptable, it becomes a sign of trust instead of distrust. The more frequently people have sexual intercourse and the more partners they have it with, the higher their risk of unwanted outcomes, and the greater their need to trust their partners. Trust is just as important between sex workers and clients and between young people as between stable couples. Condom names such as Prudence and Maximum, both African brands, reflect the fact that condoms can be promoted to provide a sense of trust. That includes trust not only in a partner but also trust in the condom to protect.

Public health programmes work best when they are carried out among an informed and involved population, and condom promotion campaigns are no exception. Condom use campaigns, e.g. in the sex industry, can be government-led, as in Thailand and other Asian countries, or carried out as a health programme, as in the Dominican Republic. It is important that they are designed and implemented by and with those they are intended for, however, to protect and promote the rights and well-being of the target population as well as the public health. This is a form of programme-level trust that can easily be left out of the equation to detrimental effect, such as in a number of cases reported in Asia where sex workers have been rounded up by local police and the military for not using condoms and their rights violated.

Who will champion the condom?

Condoms were conspicuously absent as a topic at the International AIDS Conference in Toronto in August 2006, including, outrageously, in the plenary on prevention.Footnote* In May 2006, Sudan’s health minister, Tabitha Sokaya, provoked a political storm by publicly advocating condom use to stem the country’s growing HIV epidemic. In response, the opposition National Congress Party called for her resignation.Citation7 In Uganda, where Museveni was a strong proponent of condoms early on in the AIDS epidemic, he now stands by his wife, who with PEPFAR money in both hands, is an active opponent of condom use. Here, then, in miniature, are some of the real reasons why the HIV epidemic is still raging.

We call on HIV prevention and sexual and reproductive rights advocates to begin championing the condom. However, it really needs a large international organisation with clout to step into the breach and conduct an international condom promotion campaign. What are the IPPF and UNAIDS doing? Not very much, I’m told. In the UN system, that’s UNFPA’s job, I’m told, and to give UNFPA credit they have been increasing their condom distribution for several years, but it’s still a tiny amount. What about WHO, isn’t it time for a safer sex campaign from there? Look how successful “3 × 5” was in jump-starting access to treatment in so many developing countries.

How about “No condom – No sex” as the theme of the next international AIDS conference and of World AIDS Day?

Meanwhile, in June 2006, RHM co-organised a small international workshop on condoms with the International HIV/AIDS Alliance that was attended by 32 participants from around the world who are working to promote condoms and safer sex. The workshop was in preparation for this journal issue, to bring together sex-positive perspectives on condoms. In 2005, we produced two condom postcards, using artwork by a Brazilian condom dress designer, Adriana Bertini, and sent them out as New Year’s cards. In August we took the postcards to the AIDS conference, where they went like hotcakes and at the next conference we plan to take many more such promotional materials. Surprisingly, the postcards were among the few items of condom promotional material in the entire Global Village. We also put together a collection of abstracts from PubMed on condoms, which can be found on the RHM website at <www.rhmjournal.org.uk> and the Alliance is putting together a report and all the presentations from our June workshop on a CD-rom, which will also be on their website, at: <www.aidsalliance.org/sw39345.asp>.

What’s right about condoms? Almost everything!

Condoms bring peace of mind. Condoms protect and save lives. They are the here and now of prevention and protection. Condoms, those baggy little bits of latex or polyurethane or nitrile that slide ever so nicely onto the penis and into the mouth, vagina and anus. Weigh almost nothing. Can be lubricated to avoid dryness. Transfer warmth and sensation. Keep the sheets dry afterwards. Come in different sizes, textures, colours and even flavours (well, male condoms anyway), and can be made as sexy and as much a part of the pleasure of sex as people have the imagination to invent. Condoms, that are so strong and so thin these days that once you have learned to slip one on or in, which after all only takes a bit of practice (maybe 10 or 20 times), you need hardly notice it’s there. Condoms, the least expensive, most effective form of prevention of sexual transmission of HIV, no matter what your sexual orientation, giving more protection than anything else available. Condoms, that not only prevent sexual transmission of HIV, but also unwanted pregnancy and most sexually transmitted infections, including the human papillomaviruses that can trigger cervical cancer.

The biggest complaint made about condoms is that they reduce sexual pleasure. It’s true, they can have this drawback, but it’s the entrenched belief that they have to reduce sexual pleasure that affects people more than anything. Even so, is it a good enough reason not to use them? No! All the evidence says that the negative effect of condom use on sexual pleasure is primarily linked with early experiences of using them. For example, men may find themselves unable to maintain an erection while a male condom is being put onCitation8 or a female condom put in, and women too may experience loss of physical excitement. But it’s important to persevere – all that’s needed is a little help. Obviously, this is an issue that must be taken seriously when promoting condoms. Partners should be encouraged to talk about and find ways to overcome this problem instead of letting it defeat them. Other problems? In the June condom workshop, Juliet Richters pointed out that experienced condom users sometimes have more negative attitudes about condoms than non-users, because they know condoms can sometimes smell or feel bad, and sometimes break or slip. It’s crucial to admit the reality of such experiences, but also to stress that they don’t need to happen very often. And the evidence is that even if condoms slip or break it is still safer to have used them.Citation9

Condoms can and are becoming a normal part of sex for a growing number of people, as they used to be in many countries before non-barrier contraception took over. All the evidence is that the decision to use condoms depends mainly on social acceptability (“All my friends use condoms”, “It’s responsible to use condoms”).Citation10 So if you want to convince others to use them, hey ho, it’s easy, use them yourself!

Drawbacks notwithstanding, making sex pleasurable takes practice – with or without condoms. Condoms are easy to blame when in fact people lack confidence about whether they’re good at sex more generally. Condom promotion needs to address what really makes sex pleasurable, because with practice condoms need not be an obstacle to pleasure at all. They can be sexualised or become an unobtrusive background item when having sex, as Anne Philpott and Wendy Knerr’s paper about the work of the Pleasure Project in this issue wonderfully illustrates. And that includes female condoms.

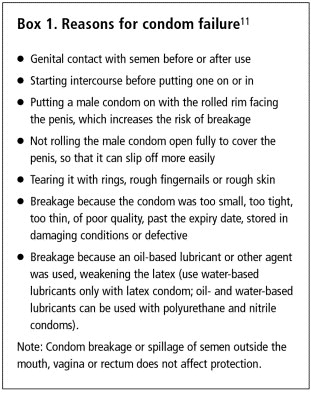

However, condom failure does occur. Most of the time, however, the failure is not the condom’s but because people didn’t use one. The main reasons for condom failure are shown in Box 1.

These reasons for failure should not be a signal to give up on condoms, but to talk through with a partner how to avoid condom failure. Post-exposure prophylaxis against HIV and emergency contraception, with the back-up of abortion, are both ways to reduce the risk if a condom was not used or if there is reason to think condom failure has occurred.

Condom design and availability

Condoms have been around since ancient Egyptian times, and have come in all sorts of sizes and shapes (), made from oiled paper, fish bladders, animal gut, leather and even tortoiseshell, which was supposedly favoured by the Japanese.Citation12 Happily, variety is beginning to make a comeback. Male condoms have long come in different sizes, and a paper by Alice Welbourn in this issue asks when female condoms will as well. Craig Darden and Christopher Purdy, who work for DKT Marketing in Brazil and Indonesia, have papers in this issue about affair condoms developed specifically for men who have sex with men and Fiesta for young people, respectively. These include different colours, textures, tastes and shapes, including a baggy male condom, and targeted social marketing campaigns.

Durex, a major international commercial male condom manufacturer, carried out a survey on penis size among 3,000 men not long ago and used the research to change the shape of the majority of their condoms, which they describe as “easy on” and more comfortable to wear. They have also produced a condom with ribs and dots on both sides, one called Play Tingle that is designed to create tingling sensations, a benzocaine condom called Performa and a polyurethane one called Avanti.Citation12

Figure 1 Some ancient condomsCitation13

With all the talk about women needing methods they have some control over, perhaps it’s time to suggest that women can gain almost as much control over male condom use as they can over female condom use through talking with their partners and negotiation. But if some women feel they have more control with female condom use, as Alice Welbourn’s paper suggests, then why are so few female condoms being used? Yes, cost is a serious problem but perhaps the more important reason is that so few are being produced. Why is this? Where is the financial support to set up more production sites? Where are the competitors, whether social marketing or commercial? And why hasn’t the Female Condom Company learned from male condom producers that packaging and promotion sell condoms? There may be a new version of the female condom, as a letter from Taina Nakari in this issue reports, but female condom packaging still looks as if it is meant for sanitary towels.

In the June condom workshop, Anne Philpott introduced the female condom as a sex toy wrapped in a pretty package and had the whole room roaring with approval at the difference it made. Yes, female condoms are more expensive than male condoms, but unlike male condoms, and especially if they are in short supply, female condoms can be re-used several times. Are national programmes that have introduced female condoms, but who have few resources, teaching women about re-use, to help address the lack of adequate supplies? Do the directions for use with the female condom say this? How many people actually know re-use is even possible.Citation14

A study of re-use in Johannesburg, South Africa, among a group of 100 women aged 17–43 who were attending a family planning or STI clinic, and another group of 50 women aged 18–40 at high risk of STIs, including 80% who were sex workers, found that the concept of re-use of the female condom was acceptable to 93%, while 83% said they would be willing to re-use the female condom. The 49 women who did re-use female condoms up to seven times during the study said the steps involved in cleaning the condom for re-use were easy to perform and acceptable.Citation15

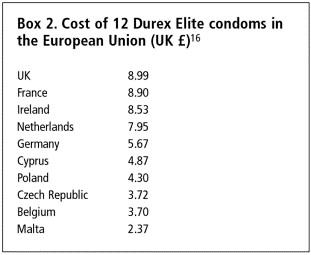

Speaking of cost, female condoms are not the only problem; check out the differential in cost for the same packet of 12 Durex Elite condoms in the European Union (Box 2).

Promoting safer sex

The decision to practise safer sex is not merely an individual decision, based on knowledge of the methods available, but one that is also influenced by powerful social and sexual norms. HIV is still primarily an epidemic among men who have sex with men in some countries, among injection drugs users and ethnic minorities in others, in still others among sex workers and their clients, and in some cases among other marginalised groups, such as street children, refugees and other displaced persons, who are vulnerable to wide-scale rape. Thanks to antiretroviral treatment, many more people are living with HIV longer, and a whole generation of young people who were born with HIV have become adolescents. People for whom the risk of HIV is high need to know about protecting themselves and others, and condom use campaigns among them should be a priority as these help to prevent high rates of HIV in the wider population. Where the HIV epidemic has become more generalised, however, safer sex becomes increasingly important for everyone.

Programmes such as the 100% condom use programmes in the sex industry can be effective at keeping HIV incidence down where it is still possible to prevent HIV moving into the wider population. They should also be targeted at injection drug users in countries where much HIV transmission is through unclean needles and then to the sexual partners of drug users. But in countries where the epidemic is already generalised, and because marriage is not a guarantee of safety for either partner, it is crucial to promote 100% condom use to everyone who is having sex.

Women are mostly getting infected at a younger age than men as a consequence of sexual networking patterns. Women tend to have sexual relationships with men at least a few years older, whether inside or outside marriage. In some cultures, men marry women up to ten years younger, and they often have extra-marital relations with younger women (and with younger men). In each such relationship, the older man has had more chance to be exposed to HIV, both because he is older and because he is likely to have had more sexual relationships. Hence, the chain of transmission means more infected women ().Citation17 That does not mean, however, that men are less at risk of HIV. Quite the contrary; men are more at risk at older ages. Thus, condom promotion campaigns need to address actual, local sexual networking patterns to be effective.

Figure 2 The chain of transmission due to sexual networking: an example Citation17

Having sex with more than one lifetime partner is a common experience. Calling on people who want to have sex to abstain from sex does not work from a public health point of view. There is no doubt that many people are mutually faithful to one partner over their lifetimes. HIV, however, is being transmitted in sex acts occurring outside this norm.Citation18 To protect the public health, the practice of safer sex, promoted in a sex-positive way, is necessary. It includes saying no to unwanted sex, being faithful, having fewer partners, having sex that does not include intercourse, and using condoms, condoms, condoms. Not just to prevent HIV and STIs, but also to prevent unwanted pregnancy, STI-related infertility and negative pregnancy outcomes, and cervical cancer – and most powerfully to protect children and for partners to protect each other.

Men and women repeat and practise the socio-sexual norms they have been exposed to. For example, most people say that unprotected sex is more pleasurable or that sex can only be pleasurable if it is unprotected. Yes, sex involves the blurring of the boundaries between two people, and barrier methods both symbolically and physically are perceived to limit pleasure. However, many who hold this vision have never tested these beliefs by becoming adept at using condoms and seeing how unimportant the reduction in pleasure actually is. There are many ways to avoid HIV and sexually transmitted infections and still have passionate sex; it only takes a little time to become good at them.

International AIDS Conference, Toronto, August 2006

What was new? Access to treatment has massively increased in Africa and other developing countries. The fact that highly active antiretroviral treatment (HAART) can save the lives of people in poor countries and contribute to prevention by reducing viral load and therefore the risk of transmission, is now proven and widely accepted (except by the South African government), an incredible transformation of policy, considering the situation even five years ago. The possibility of an HIV vaccine has also been revived with increased understanding of what happens on the surface of the virus. Moreover, the importance of harm reduction as regards injection drug use, especially free needle exchange and the offer of methadone to drug users, was also given centre stage more than once. Very importantly, a handful of cases of “superinfection” have been identified in a small study (8 of 57) in which re-infection by more than one HIV subtype has been identified 2–5 years after first infection. It is as yet unclear whether this affects antibody production or disease progression, but calls for greater precautionary attention to protection against re-infection between people with HIV.

We heard that generic antiretroviral (ARV) drugs produced in India supply 50% of the inexpensive drugs in developing countries. The implications if India gets sucked into global trade agreements that threaten generic production are very bad. Worse, we heard that sustainability of ARV treatment programmes is in question because new agreements with the Global Fund for the next round had not yet been secured and current funds would run out at the end of 2006. The biggest concern was that people who had been able to go on ARV treatment would have to stop again, reversing all the health gains made.

A pre-conference session on prevention of mother-to-child transmission (PMTCT) pointed out that ten years after the first PMTCT pilot programmes began to be set up, 100 countries have national PMTCT programmes and 11 further countries now have pilot sites. Yet in 2004 less than 10% of HIV positive pregnant women were receiving PMTCT drugs, while only 5% out of an estimated 20–30% of HIV positive pregnant women who needed it were receiving ARVs to treat their own infection. At other moments in the conference, we heard that less than 10% of injection drug users and less than 10% of men who have sex with men have got access to ARVs as well. These figures indicate that preventive programmatic interventions of all kinds take a long, slow time to reach enough people.

Amazing is the only word for the range of prevention modalities that were described and could be developed, including microbicides containing antiretrovirals, a vaginal ring with about a month’s delivery of antiretrovirals, cervical barriers, male circumcision, pre-exposure prophylaxis against HIV (as well as the proven post-exposure form), and new STI treatments – suppressive therapy for herpes and a vaccine against human papillomavirus. All, however, require either high technical input or major provider training and/or health service involvement, which in both cases means resources are necessary. With condoms still the only item on the prevention list that is actual, the issue of prioritising where efforts and funding should be placed as regards developing and disseminating more modes of prevention must become a major debate, but that debate did not take place in Toronto. In fact, there was practically no debate about anything at all.

Throughout the week, most people were probably lucky if they got to speak once from the floor for a couple of minutes. The conference was awash with five-minute presentations, as usual, and even more awash with posters that few people probably had time to read or discuss. In most sessions, there were hundreds of people in attendance who remained passive observers or were reduced to clapping to show their views. Perhaps the conference is far more of a learning experience for those attending it for the first or second time than for those who have been attending for many years. Is that intentional, let alone a good idea? I doubt it. Nor does it seem to be the most productive use of the vast amount of experience represented by the more than 30,000 people who attended this time.

Most importantly in this regard, perhaps, is that a whole new generation of people is now attending the conference, whose experiences are entirely different from that of people in the 1980s and 90s. For many of them, what was learned in earlier years was unknown. Young people were there in force (1,000 young activists were funded to attend, a major success) but many spoke of having to keep their sexuality a secret and of their needs growing up with HIV being unaddressed. One spoke eloquently of the difference between prevention of HIV transmission and AIDS prevention for HIV positive people as not being recognised at all. The need for sexuality education was considered a “good thing” from the lips of many, but where were the participants from Ministries of Education, let alone Health, who would take all this home and apply it?

It might be time for a major re-think about the role of the international AIDS conferences. Richard Horton, editor of the Lancet, said: “The grip of AIDS will only be broken by effective programmes at country level… What never happens [at the conference] is an event or process to develop integrated country strategies that focus only on the country – not on the interests of the agency, funder or constituency (academic, political or activist).” This, he says, should be the purpose of the conference, and that the conference should be used as a global accountability mechanism to monitor country progress, holding all parties responsible for the part they play in defeating AIDS and setting specific, measurable objectives for the succeeding two years.Citation19

This is an excellent vision. It means that the framework of an entirely abstract-and poster-driven conference should be revised, however. We need cross-track, floor-dominated discussions and debates on all the issues and policies where there is uncertainty or disagreement on the way forward, which have hampered efforts to deliver successful programmes. The ways in which the work is funded also need challenging. Instead of turning donors into Hollywood celebrities to be praised uncritically for what they choose to fund, donors ought to have to present and defend their policies to governments and activists, and work on ironing out the conflicts between each other’s priorities. There should also be sessions in which different perspectives are put forward by their most eloquent proponents, not only to be debated from the floor but also with the intention of forging a consensus on as many aspects of the issue as possible, the results of which can then be published to help to inform policy and programmes. This means inviting experts on specific topics to run such sessions, of which condoms and HIV testing policy are only two examples, instead of continuing to work primarily through centralised, committee-led planning based on tracks. Such sessions should be structured to allow proper time to be given for comment and argument from the floor. This cannot be accomplished in 60 or 90 minutes.

Perhaps there should be a whole day of country-focused meetings and half days on programmatic issues such as children and HIV, STI control and safer sex promotion.

At the very least, though, attention to how to promote safer sex as part of a comprehensive programme of sexuality education for both young people and adults, including condom promotion, in spite of religious and donor blockage, must be taken on board as a priority in Mexico in 2008.

In memoriam

In this journal issue, both Nasreen Huq and José Barzelatto are remembered. Both will be greatly missed as colleagues and friends.

There are many people whose lives José Barzelatto touched in an important and lasting way, and I am one of them. I have always thought of him as the father of Reproductive Health Matters, because he gave us our first grant and was a constant supporter.

RHM website

With all current and back issues of the RHM journal on the Elsevier ScienceDirect website, available to all subscribers, including free subscribers, we are hoping to revamp RHM’s own website during 2007, and would welcome suggestions of the kinds of things you would log in there to use and which audiences you think we should serve. We are already expanding the news sections, and putting news items up weekly. So if you haven’t visited <www.rhmjournal.org.uk> for a while, do so today to get the latest news – and let us know what you think!

Notes

* When I asked the president of the International AIDS Society and co-chair of the conference, Helene Gayle, why condoms did not get a speaker of their own or barely a mention in the prevention plenary, she replied: “We thought the speakers would cover them more, but we can’t control what they present.” Really?

References

- R Stein. Health workers’ choice debated: proposals back right not to treat. Washington Post. 30 January. 2006

- J Santelli, M Ott, M Lyon. Abstinence and abstinence-only education: a review of US policies and programmes. Journal of Adolescent Health. 38: 2006; 72–81.

- D Kirby, BA Laris, L Rolleri. The impact of sex and HIV education programs in schools and communities on sexual behaviors among young adults. 2006; Family Health International: Research Triangle Park.

- KR Davis, SC Weller. The effectiveness of condoms in reducing heterosexual transmission of HIV. Family Planning Perspectives. 31(6): 1999; 272–279.

- Dutch Catholic bishop urges condom use. At: <www.radionetherlands.nl/current affairs/aid060901mc>. 8 September 2006.

- J Cleland, SC Watkins. The key lesson of family planning programmes for HIV/AIDS control. AIDS. 20(1): 2006; 1–3.

- P Moszynski. Sudanese health minister’s advocacy of condoms sparks controversy. BMJ. 332(27 May): 2006; 1233.

- J Richters. Researching condoms: the laboratory and the bedroom. Reproductive Health Matters. 2(3): 1994; 55–61. At: <www.rhmjournal.org.uk/PDFs/03richt1.pdf>.

- TL Walsh, RG Freziers, K Peacock. Use of prostate-specific antigen (PSA) to measure semen exposure resulting from male condom failures: implications for contraceptive efficacy and the prevention of sexually transmitted disease. Contraception. 67: 2003; 139–150.

- Richters J. Condoms, sex and sexuality. Presentation at Condoms: An International Workshop. London, 21–23 June 2006.

- Berer M with Ray S. Contraceptives and condoms. Women and HIV/AIDS: An International Resource Book. London: Pandora, 1993. p.153.

- S Solanki. The future of condoms and their role in the fight against HIV and AIDS. Impact: National AIDS Trust Policy Bulletin No.10. June. 2005

- From: Cover illustration. Women’s Global Network for Reproductive Rights Newsletter. 1986. Also in: Berer M with Ray S. Contraceptives and condoms. Women and HIV/AIDS: An International Resource Book. London: Pandora, 1993. p.166.

- World Health Organization. Considerations regarding re-use of the female condom: Information Update, 10 July 2002. Reproductive Health Matters. 10(20): 2002; 182–186. At: <http://www.who.int/reproductive-health/stis/docs/report_reuse.pdf>.

- AE Pettifor, ME Beksinska, HV Rees. The acceptability of reuse of the female condom among urban South African women. Journal of Urban Health: Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine. 78(4): 2001; 647–657.

- Eurofile. Guardian (UK). 25 February 2006.

- Berer M with Ray S. Epidemiology. Women and HIV/AIDS: An International Resource Book. London: Pandora, 1993. p.45.

- GW Dowsett. Some considerations on sexuality and gender in the context of AIDS. Reproductive Health Matters. 11(22): 2003; 21–29.

- R Horton. A prescription for AIDS 2006-2010 [Perspective]. Lancet. 368: 2006; 716–718.