Abstract

This paper provides an overview of legal, religious, medical and social factors that serve to support or hinder women's access to safe abortion services in the 21 predominantly Muslim countries of the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) region, where one in ten pregnancies ends in abortion. Reform efforts, including progressive interpretations of Islam, have resulted in laws allowing for early abortion on request in two countries; six others permit abortion on health grounds and three more also allow abortion in cases of rape or fetal impairment. However, medical and social factors limit access to safe abortion services in all but Turkey and Tunisia. To address this situation, efforts are increasing in a few countries to introduce post-abortion care, document the magnitude of unsafe abortion and understand women's experience of unplanned pregnancy. Religious fatāwa have been issued allowing abortions in certain circumstances. An understanding of variations in Muslim beliefs and practices, and the interplay between politics, religion, history and reproductive rights is key to understanding abortion in different Muslim societies. More needs to be done to build on efforts to increase women's rights, engage community leaders, support progressive religious leaders and government officials and promote advocacy among health professionals.

Résumé

Cet article passe en revue les facteurs juridiques, religieux, médicaux et sociaux qui favorisent ou entravent l'accès des femmes à des services d'avortement médicalisé dans les 21 pays musulmans du Moyen-Orient et d'Afrique du Nord, où une grossesse sur dix se termine par un avortement. Les efforts de réforme, notamment les interprétations progressistes de l'Islam, ont abouti à des lois autorisant un avortement précoce sur demande dans deux pays ; six autres permettent l'avortement pour des raisons de santé et trois autres aussi en cas de viol ou de malformation fłtale. Néanmoins, des facteurs médicaux et sociaux limitent l'accès à l'avortement médicalisé dans tous les pays, sauf la Turquie et la Tunisie. Pour corriger cette situation, quelques pays redoublent d'efforts pour introduire les soins post-avortement, réunir des informations sur le nombre d'avortements à risque et comprendre l'expérience qu'ont les femmes des grossesses non planifiées. Des fatawa religieuses ont autorisé les avortements dans certaines circonstances. Il est essentiel d'appréhender les variations des croyances et pratiques musulmanes, et les influences entre la politique, la religion, l'histoire et les droits génésiques pour comprendre l'avortement dans différentes sociétés musulmanes. Il faut faire plus pour accroître les droits des femmes, recruter les responsables communautaires, soutenir les chefs religieux et les fonctionnaires gouvernementaux progressistes, et promouvoir le travail de plaidoyer parmi les professionnels de la santé.

Resumen

En este artículo se expone una visión general de los factores jurídicos, religiosos, médicos y sociales que influyen en apoyar u obstaculizar el acceso a los servicios de aborto seguro en los 21 países musulmanes del Oriente Medio y Ãfrica Septentrional, donde uno de cada diez embarazos termina en aborto. Los esfuerzos por traer reformas, como las interpretaciones progresistas de Islam, han propiciado leyes que permiten el aborto temprano a petición en dos países; en seis otros países se permite el aborto por motivos de salud, y en tres más también se permite en casos de violación o de discapacidad fetal. No obstante, los factores médicos y sociales limitan el acceso a los servicios de aborto seguro en todos los países, salvo Turquía y Túnez. Para tratar esta situación, en algunos países se han ido escalando los esfuerzos por institucionalizar la atención postaborto, documentar la magnitud del aborto inseguro y entender la experiencia de las mujeres con el embarazo no planeado. Se han emitido fatawas religiosas que permiten el aborto en ciertos casos. El comprender las variaciones en las creencias y prácticas musulmanas, y la interacción entre la política, la religión, la historia y los derechos reproductivos, es fundamental para entender el aborto en las diferentes sociedades musulmanas. Aún se debe hacer más por aumentar los derechos de las mujeres, atraer a los líderes comunitarios, apoyar a los líderes religiosos y funcionarios gubernamentales progresistas y fomentar el activadades de defensa entre los profesionales de la salud.

The Middle East and North African (MENA) region,Footnote* stretching from Morocco to Iran, is highly diverse in levels of socio-economic development, political systems, health indicators, women's status, official interpretations of Islam and individual religious expression. The region has some of the world's lowest and highest population growth rates. Contraceptive prevalence rates range from less than 10% in Mauritania and the Sudan to 63% in Tunisia and 74% in Iran.Citation1 Total fertility rates have dropped significantly in Tunisia and Morocco (to 2.1 and 2.4, respectively), whereas they are still relatively high in Saudi Arabia (5.2). While reproduction and motherhood are a source of prestige and identity across MENA countries, only 33% of the poorest women in Egypt and Morocco and 7% in Yemen have access to a skilled birth attendant.Citation2

The need for sexual and reproductive health information and services has never been greater in the region. The biggest cohort of adolescents will soon be entering reproductive age and marital patterns changing. One-third of the population is aged 15–24 in many countries in the region; the cohort aged 20–29 is expected to grow by 60% in Iraq and 80% in Yemen by 2025.Citation1 While age at sexual initiation is decreasing, average age at marriage has increased, leaving a larger gap for unwanted pregnancies to occur. The number of ever-married women ages 15–19 has dropped from 22% to 10% in Egypt, 10% to 1% in Tunisia and 57% to 8% in the United Arab Emirates in the past 20 years.Citation1 While considered taboo, premarital sex and unwanted pregnancies are increasingly common among adolescents and young people in key countries across the region.Citation3Citation4 Yet only a few governments – Iran, Morocco and Tunisia – support sexual and reproductive health programmes for young people.Citation4Citation5 Efforts are directed towards increasing effective contraceptive use especially among unmarried individuals and integrating sexual and reproductive education in primary and secondary schools.Citation3Citation4

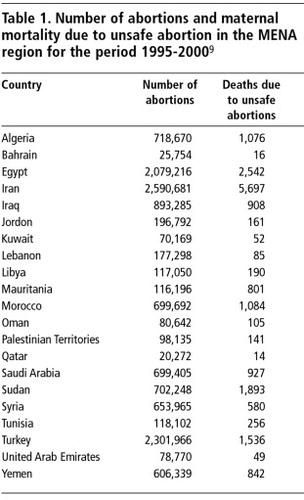

Officially, one in ten pregnancies ends in abortionCitation6 and unsafe abortions constitute at least 6% of maternal deaths in the region.Citation7 In a 1998 hospital-based study in Egypt, one in every five obstetric admissions was for post-abortion treatment,Citation8 and over 1,000 unsafe abortions take place every day in Iran.Citation9

This paper provides an overview of the factors that serve to support or hinder women's access to safe abortion services in the MENA region, underscoring differences across and within countries. The data on which it is based are from Popline and Medline searches covering the past 20 years; reviews of national newspapers, primarily Egyptian and Moroccan; and interviews with key health professionals and representatives of women's organisations in Egypt, Morocco, Tunisia and Turkey between 2001 and 2006.

Islam, family planning and abortion: different interpretations

Islam is a diverse religion, and its interpretation differs across the Muslim world. Individual interpretation is a key Islamic principle; Muslims are encouraged to read and analyse traditional religious sources to find solutions to contemporary problems. Four official schools of interpretation exist in Sunni Islam, while Shiites have their own methods of jurisprudence and thought. These schools have developed a significant body of shari'a (Islamic law), which differs from country to country. In cases where Islamic jurisprudence is unclear, religious leaders will issue fatāwa Footnote* (non-binding religious edicts) to provide guidance.Citation10

Pronouncements on family planning and abortion have a long history in Muslim thought. Early Muslim

theologians supported contraception as long as both partners consented. Most scholars agreed abortions were allowed if pregnancies ended before ensoulment of the fetus, described as occurring between 40, 90 or 120 days after conception, depending on the school of thought.Citation11 Usually, a justifiable reason is needed for terminating a pregnancy, e.g. to protect a breastfeeding child, socio-economic concerns or health reasons.Citation12Four main positions on abortion prior to ensoulment currently exist across these schools of thought: i) abortion is allowed, ii) abortion is allowed under certain circumstances, iii) abortion is disapproved of and iv) abortion is forbidden.Citation11 Support for abortion and the belief that life begins at ensoulment is based primarily on the following Qur'anic verse, which discusses the different stages (semen, blood clot, bones and flesh) of fetal development:

“Man We did create from a quintessence (of clay); then We placed him as (a drop of) sperm in a place of rest, firmly fixed; then We made the sperm into a clot of congealed blood; then of that clot We made a (fetus) lump; then We made out of that lump bones and clothed the bones with flesh; then We developed out of it another creature. So blessed be Allah the Best to create!” Citation13

Research in Egypt and Turkey demonstrates that abortions were socially acceptable and widely available until the late 19th century.Citation14Citation15 The legal and medical status of abortion than began to change. Midwives performed abortions until the professionalisation of medicine, when the practice was limited to physicians.Citation15 Some historians argue that women's rights, including their reproductive rights, diminished as European laws were incorporated into Middle Eastern legal systems.Citation16

In the 1960s, several key meetings brought together muftis, health professionals and others to discuss Muslim positions after many national governments decided to implement family planning programmes. A pan-Islamic conference in Cairo in 1965 and another in Kuala Lumpur in 1969 approved the use of birth control for economic reasons, defined as the inability to support additional offspring.Citation17 This was an important advance, as opponents of family planning (and abortion) had often pointed to Qur'anic passages stating that Allah will provide for all human beings. A subsequent international conference on Islam and family planning in Rabat in 1971 concluded that Islam permits birth control to space births, forbids sterilisation except in cases of personal necessity and forbids abortion after the fourth month of pregnancy unless the woman's life is in danger.Citation17

In 1992, in a meeting on unsafe abortion and sexual health in the Arab World, the participants agreed that “unsafe abortion was a major public health problem in almost all countries, and that governments and family planning associations have a special responsibility to face up to the problem, consider reviewing outdated laws where possible, reduce the toll of unsafe abortion by better and more humane treatment and provide better contraceptive services to women at risk and women who had undergone abortions”.Citation18

Today, positions on abortion continue to vary, though family planning is encouraged in practically all MENA countries. Abortion is generally forbidden after the fetus achieves ensoulment except to save the woman's life. Interpretations that allow for abortion are based on fetal development, gestational age and the circumstances of the pregnant woman; they rarely mention fetal rights or when life begins. It is accepted that maternal life takes precedence, at least until the fetus achieves the status of person.Citation11 The life of existing children is often considered more important than that of the fetus. If a woman becomes pregnant during breastfeeding, it is generally accepted that another infant might put the existing child at risk. All schools of thought forbid termination of pregnancy that results from illicit sexual activity, such as an extra-marital relationship.

Contemporary fatāwa have been issued in certain countries that add legal indications to otherwise restrictive laws. A fatwa in 1991 in Saudi Arabia allowed for abortion in the first 120 days after conception in the case of fetal impairment.Citation19 In Iran both the Grand Mufti Ayatollah Yusuf Saanei and the Ayatollah Ali Khameni issued two fatāwa in 2005 allowing for abortion under certain circumstances. The one provided for abortion in cases of genetic disorder in the first trimester; the other allowed abortion in the first trimester if a woman's health and life were at risk.Citation20Citation21

Rape is increasingly recognised by Muslim religious leaders as a legitimate reason for abortion. The Egyptian Grand Sheikh of al-Azhar, Muhammed Sayed Tantawi, issued a fatwa in 1998, stating that unmarried women who had been raped should have access to abortion.Citation22 In 2004, he stated that abortion must be provided if the woman's life was in danger and he approved a draft bill that included rape as an indication.Citation23 In Algeria, the Islamic Supreme Council issued a fatwa in 1998, stating that abortions were allowed in cases of rape, as rape was being used by religious extremists as a weapon of war.Citation24 The Algerian government stated in the United Nations that abortion was allowed in cases of rape. However, neither of these fatāwa was translated into law. In contrast, after discussions about the rapes of Kuwaiti women by Iraqi soldiers during the first Gulf War, Kuwaiti muftis decided that rape did not justify the need for legal abortion.Citation12 Yet their arguments – that life begins at conception and the innocent life of the fetus should be protected – had more in common with fundamentalist Christian views than Islamic jurisprudence.

Religious leaders are increasingly playing a role in discussing abortion law reform and more attention is being given to the social and medical reasons for abortion. In several countries, including Algeria, Egypt, Iran and Saudi Arabia, contemporary fatāwa support abortion in cases of rape, fetal impairment and risk to the woman's life and health. While religious support for abortion is important, the impetus for such debates is not necessarily women's rights. In Egypt, the Grand Mufti argued that rape victims should have access to abortions and to reconstructive hymen surgery to preserve female marriageability and virginity.Citation22

While fatāwa have generated considerable debate about abortion, they are not legally binding unless they are translated into law. Moreover, the patriarchal tradition allows only men to serve as muftis and to interpret religious texts. The issuing of fatāwa has been criticised by women's groups in the region as an intrusion of religion into secular matters. In Algeria, for example, while muftis declared that rape should be a grounds for abortion, some women's groups said that the secular law already included a mental health indication for abortion (Personal communication, Caroline Brac de la Perrière, Algerian women's rights activist, March 2006).

Clearly, different lenses can be used to read Islamic religious texts. However, official religious leaders and interpreters in the MENA region are all men. An important movement is that of women, such as the Women and Memory Forum in Egypt, claiming the right to re-interpret religious texts and history in light of contemporary realities and from a feminist perspective. Muslim women scholars have also written about women's reproductive rights in Islam.Citation25 These efforts and others seek to highlight the basic Muslim principles of justice and equality, as well as the right of women to life, health and safety.

Abortion laws and policies: an overview

The majority of MENA countries recognise Islam as the state religion. Most have dual systems of law. Secular codes, often based on colonial law, regulate most legal matters, while Islamic law covers the family, marriage, divorce, inheritance and custody. Turkey is the one fully secular country in the region, while only Iran, Saudi Arabia and Sudan apply Islamic law to all matters of jurisprudence, including abortion.

French colonial law has influenced abortion policy in Algeria, Iran, Lebanon, Mauritania, Morocco, Syria and Tunisia; British codes are still on the books in Qatar and several Gulf states, while Libya's legislation is based on Italian law. Since independence, several countries have liberalised their abortion laws and the circumstances under which abortion should be legal. Laws have also been reformed to adhere more closely to Islamic principles, including regarding fetal development, the commencement of life and punishment and compensation for illegal abortion.

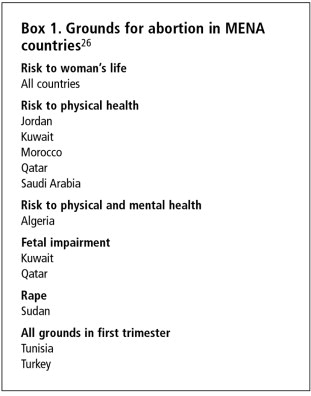

All countries include saving the pregnant woman's life as a legal indication; close to half permit abortion in case of risk to physical health, and a few also include mental health (Box 1). Where abortion is restricted, penal and criminal codes include harsh sanctions for the person responsible for inducing the abortion and for the woman seeking abortion. Laws do not punish the man involved in the unwanted pregnancy unless he tries to perform the abortion himself.

A distinctive characteristic of Islamic law is that the punishment for performing an illegal abortion consists of payment of compensation to the couple whose fetus it was, the amount of which depends on the stage of fetal development. Children's rights activists in Iran have highlighted the need to eliminate inconsistencies in Iranian law as one reason why the abortion law should be reformed, e.g. the punishment for killing a child who is already born is less than that for terminating a pregnancy.Citation27

Most abortion laws in the region are punitive and legal services are restricted. Only Tunisia (1973) and Turkey (1983) allow for early abortion on request. Proposals to expand legal indications for abortion have been presented in seven other countries: Kuwait (1981), Qatar (1983), Algeria (1985), Saudi Arabia (1991), Sudan (1991), Egypt (2005) and Iran (2005). In Kuwait, Sudan, Turkey and Qatar, these proposals became law.

Liberal laws

Before Tunisia's independence in 1956, policies and legislation were pro-natalist in nature, inspired by French law. In 1964, Tunisia established its first population policy, whose main objectives were to improve the health of women, ensure the fullest development of families, control population growthCitation28 and reduce the negative health consequences of unsafe abortions. At the time, women suffering from complications of illegal abortions occupied 25% of all Tunisian hospital beds.Citation29 In 1965, the 1940 penal code was replaced. The new code allowed abortion on request if the abortion was performed before the end of the first trimester, the woman had at least five living children and the written agreement of both husband and wife was obtained.Citation28 Unsafe abortions continued, however, because many women could not meet the parity requirement.

Women's groups lobbied for the removal of these restrictions and presented the Minister of Health with various studies. In 1973, the parity requirement and the written consent of the husband were removed. The amended law allowed abortion for health and social indications and in cases of fetal impairment in the first trimester when performed by a qualified physician in a public or private hospital or clinic, and after this period for risk to the woman's physical or mental health and fetal impairment.Citation30

In Tunisia, abortion law reform was part of a larger post-colonial effort to increase women's status and rights, limit population growth and promote socio-economic development. Tunisia was the first MENA country to liberalise its abortion law, abolish polygamy and give men and women the same rights to divorce, among other things, in its personal status code. These reforms were based on a progressive interpretation of Islamic principles and beliefs.Citation31 The abortion law is unique in the region in that spousal consent is not required, and women do not have to be married to obtain an abortion. Interviews with health professionals and women's activists in Tunisia point to the general social acceptance of abortion and the lack of opposition (Personal communication, Tunisian Office of Family and Population staff, April 2006). In recent years, the Tunisian government has introduced adolescent-friendly services and medical abortion into its public clinics.Citation4,32

In the late 1970s in Turkey, unsafe abortion was acknowledged as a major public health concern. Population Policy Law No.2827 was passed in 1983, authorising abortion on request up to ten weeks of pregnancy and up to 24 weeks for medical indications.Citation33 Under this law, trained nurses and midwives are authorised to insert IUDs, and general practitioners are allowed to provide abortions by vacuum aspiration, referred to as menstrual regulation, in hospitals, under the supervision of obstetrician–gynaecologists. Spousal or parental consent is required in the implementing regulation, depending on the woman's age but is not included in the actual law. Hence, no criminal action can be taken should an abortion be performed without this consent.

Three interrelated strategies were used to advocate for legal reform: i) research on the undesired consequences of unsafe abortion, its link to maternal mortality and a high rate of unwanted pregnancy; ii) introduction of simpler and safer methods for treating post-abortion complications such as manual vacuum aspiration (MVA); and iii) a cohort of trained providers of MVA (Personal communication, Ayşe Akin, September 2001, Obstetrician–Gynaecologist and professor, Hacettepe University). After considerable debate, new legislation was adopted in 1983. Obstetrician–gynaecologists and certain religious leaders were initially opposed to the new law, the former because they were providing abortions in their private clinics for high fees. Religious leaders focused on ensoulment; a compromise was reached that abortion would be legal on request until ten weeks after conception (12 weeks LMP).

Somewhat restrictive laws

The laws of Algeria, Jordan and Morocco are governed by their penal codes, based on French colonial law, that allowed abortion to save the woman's life or preserve her health. Jordan's 1971 public health law allows abortion for mental health reasons. In 1981, Kuwait became the first Gulf States to reform its law, allowing for physical and mental health indications and cases of fetal impairment. Qatar changed its law in 1983 to allow abortion in case of harm to the woman's health or fetal impairment, and Algeria's law was reformed in 1985 to include a mental health indication. Shari'a governs all of Saudi Arabia's laws and allows abortion in case of severe risk to the woman's life or health.Citation26

A draft Palestinian Public Health Law, debated in Parliament before the 2006 legislative elections, allows abortion in cases of risk to the woman's life and health (Personal communication, Rita Giacaman, Community Health Programme, Birzeit University, 2006).

Very restrictive laws

The laws of 13 of the 21 countries in the region are very restrictive, only allowing abortion if the woman's life is at risk. Under colonial penal codes, abortion was prohibited in Lebanon, Libya, Mauritania and Syria in all circumstances; those laws now allow abortion only in case of risk to the woman's life. Abortion in Yemen is governed by the 1994 penal code, based on restrictive Islamic law, which prohibits abortion except to save the life of the woman; the laws of Oman and the United Arab Emirates are similar.Citation26

Egypt's penal code prohibits abortion of an established pregnancy. Post-coital contraception and menstrual regulation, where pregnancy is not established, are sometimes condoned. Article 61 stipulates: “A person shall not be punished for a crime which is in self-defence or for defending someone else against serious danger.” This is sometimes used to condone abortion when the woman's health or life is at risk.Citation34

In Iran, abortion was allowed under certain circumstances in the early 20th century and a law was passed in 1977 allowing abortion on request. This law was overturned after the Islamic Revolution in 1979. Today, abortion in Iran is governed by the 1991 Law on Islamic Penalties, based on Shiite Islamic law, in which abortion is prohibited but principles of necessity allow abortion to save the life of the woman.Citation26 In 2005, the Iranian Parliament approved a law allowing for abortion for fetal impairment and risk to the woman's life, but the law was subsequently rejected by the Islamic Guardian Council.Citation35

The penal code of Sudan combines elements of both Islamic and English law. In 1991, as part of an ongoing effort to revise the law in accordance with Islamic law, abortion was permitted to protect the woman's life, in cases of rape if the pregnancy is of less than 90 days' duration or if the fetus is dead in the womb.Citation26

Except for Tunisia and Turkey, national variations in the restrictiveness of abortion laws cannot be predicted based only on their use of shari'a or colonial law. Mauritania's restrictive law is based on French colonial law, not Islam, and Saudi Arabia's Islamic code is more permissive than Libya's Italian-derived law.

Abortion service delivery

In spite of legal reforms, it is as yet undocumented whether women's access to safe abortion services has increased. While abortions are common across the MENA region, the majority of procedures are, by World Health Organization definitions, unsafe.Citation7 Women's access is affected by their socio-economic and marital status and rural–urban residence as well as the law. Numerous medical barriers also limit access, such as requiring the authorisation of several doctors, cumbersome requirements for rape and health indications and in all but one country, spousal consent. There is scant information on options for women seeking second-trimester abortion.Citation12

Clandestine abortion providers include gynaecologists and a range of physicians.Citation34,36,37 The quality of services varies considerably and depends on ability to pay, access to pain relief and use of modern or traditional abortion methods.Citation34 Some studies demonstrate that women can obtain legal abortions for serious health problems such as cancer, hypertension and diabetes.Citation37 Abortions are also induced using indigenous methods, including a range of herbs, medications or alcohol ingested orally or inserted rectally or vaginally, commonly the herbs hantita in Morocco, handal in Egypt and chloroquine.Citation34Citation36 Health professionals interviewed in Morocco and Egypt say that the prostaglandin misoprostol, is also increasingly being used. Medical abortion, using a combined regimen of mifepristone and misoprostol is available in Tunisia and is being introduced in Turkey.Citation32Citation38

The medical community is beginning to document and bring to light the public health impact of unsafe abortions in Algeria, Egypt, Morocco, Syria and Sudan. Efforts are being made by health professionals to implement the ICPD and ICPD+5 agreements that abortion should be safe and accessible for legal indications.Citation39Citation40 Some discussions are taking place over what constitutes a health exception and if psychological and mental well-being are included.Citation39 Interviews with providers reveal greater acceptability of abortion in cases of rape, pregnancy in single women and a severely malformed fetus.Citation19,37,41

Post-abortion care

Despite differences in legal and religious perspectives, there is generally consensus among Muslim leaders that women who have miscarried or aborted have the right to treatment.Citation42 Access to emergency obstetric and post-abortion care is a key intervention in Egypt, Morocco and Sudan.Citation39 Egypt was the pioneer in the region in research, training and advocacy on post-abortion care to reduce the risk of mortality and morbidity associated with incomplete abortion.Citation8,43–47 Training programmes in post-abortion care are in place at the prestigious Ain Shams medical school and a training hospital.Citation48 Post-abortion care has been scaled up in select medical centres and introduced as part of a comprehensive package of reproductive health and family planning services. In Syria, post-abortion care services are now part of the national sexual and reproductive health programme and a review of the abortion law is scheduled for 2006.Citation39 Health professionals in Algeria seek to promote the integration of the study of abortion in medical and midwifery schools.Citation37

Extensive training in post-abortion care, including MVA for abortions up to 12 weeks LMP, has been conducted in key medical universities and training centres in Sudan. The Sudanese Ministry of Health has included post-abortion care in its new guidelines on emergency obstetric care, and standards of reporting and protocols for service delivery are being developed. Post-abortion care services are being provided in six health centres in Khartoum, and a reproductive health information and advocacy programme with factory workers and their families was initiated in 2002.Citation49

Fetal impairment

Consanguineous (cousin-to-cousin) marriage is practised in more than 20% of marriages in Algeria and Morocco and more than 50% in Jordan and Saudi Arabia.Citation50 Genetic counselling and antenatal testing have increased, especially in countries with high rates of consanguineous marriage.Citation19Citation51

In a study among people with haemoglobin disorders in Saudi Arabia of attitudes towards antenatal diagnosis of disorders and abortion in cases of sickle cell anaemia and thalassaemia, most participants were unaware of increased risk with consanguinity and did not know about the Saudi Arabian fatwa permitting abortion in cases of fetal impairment. Close to half of the participants, who had initially rejected the idea of pregnancy termination, changed their minds when informed of the fatwa.Citation19 Similar findings in relation to haemoglobin disorders in Lebanon have been reported.Citation51

Given the still relatively high percentage of cousin-to-cousin marriages, health professionals are working to ensure that prenuptial consultations discuss the importance of contraceptive use, steps to take after miscarriage and the possibilities of genetic problems in consanguineous marriage.Citation37Citation41

Women's abortion experiences

The few existing studies from the region show that induced abortion is common and deemed necessary and justified by women under certain conditions. In Egypt and Morocco women are often more pragmatic and less moralistic than current leaders.Citation52–54 They often rely on God's compassion rather than religious authorities.Citation52

Quality of service delivery is often poor, adequate pain control lacking and post-abortion counselling insufficient.Citation52–54

A link has been documented between unwanted pregnancy, lack of access to abortion and suicide among young women. In Tunisia, a 1972 study documenting 55 suicides of unmarried pregnant womenCitation12 was used to lobby for the subsequent law reform. In an Algerian psychiatric ward, 30% of attempted suicides followed unwanted pregnancies.Citation22 This corroborates similar findings elsewhere in the Arab world.Citation18

Advocacy for safe abortion and women's organisations

While for the most part, women's groups have not addressed the issue of abortion directly, they are working to challenge the patriarchal structures that limit women's reproductive rights. In Algeria, Egypt, Jordan, Morocco and Palestine groups have lobbied for changes in discriminatory family codes, nationality and rape laws. Activists such as the Turkish Women for Women's Human Rights have made strides to define marital rape as a crime and raise community awareness about violence against women and its health impact. Organisations such as the Centre for Women's Legal Counselling in Palestine and the New Woman Foundation in Egypt are demanding that national governments respect their commitments to universal human rights standards, including gender equality and non-discrimination. Solidarité Féminine in Morocco, Association Amal in Tunisia and Darna in Algeria have formed to confront one of the consequences of restrictions on abortion: involuntary motherhood.

The Coalition for Sexual and Bodily Rights in Muslim Societies includes NGOs, activists and researchers working on sexual and reproductive rights across the MENA region.Citation55 Information about abortion globally and regionally is being produced and translated into Arabic to raise awareness.Citation56 For example, the New Woman Foundation recently published an Arabic edition of Reproductive Health Matters on abortion.Citation56

Conclusion

While conservative religious arguments are still being used to legitimise patriarchal practices, this review found great diversity in Muslim discourse, policies and individual decision-making related to abortion. Importantly, there seems to be no apparent link between state religion, individual religiosity and abortion prevalence. Iran, with one of the highest abortion prevalence rates in the region is also ruled by some of the most conservative Muslim clerics.Citation9

In a context of rapid social and demographic change and changes in women's status, the debate over abortion is central to discussions about how to reconcile women's rights with those of the community and the state. It is also about governments' obligations to their (women) citizens. Challenges to the status quo and the patriarchal traditions and conservative religious interpretations that keep abortion restricted and stigmatised, are essential.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Debbie Billings, Barbara Crane and Charlotte Hord-Smith for helpful comments. Reed Boland was instrumental in consolidating information on abortion laws. Cynthia Greenlee-Donnell and Lonna Hays gave useful editorial advice and assistance with references and tables.

Notes

* While the MENA region is religiously diverse, this paper limits its discussion to how interpretations of Islam are being used to support or hinder women's reproductive rights. I have therefore only included those countries in the region that are predominately Muslim, and excluded Cyprus and Israel. Afghanistan, Djibouti and Somalia, which are sometimes included in the MENA region, were also excluded.

* Fatwa is the singular and fatāwa the plural.

References

- World Health Organization. World Health Statistics. 2005; WHO: Geneva.

- Population Reference Bureau. Investing in Reproductive Health to Achieve Development Goals. 2005; PRB: Washington DC.

- International Planned Parenthood Foundation. Breaking the Silence and Saving Lives: IPPF Arab Regional Conference on the Implementation of the ICPD. 1996; IPPF: Cairo.

- J DeJong, R Jawad, I Mortagy. The sexual and reproductive health of young people in the Arab countries and Iran. Reproductive Health Matters. 13(25): 2005; 45–49.

- International Planned Parenthood Federation. Arab World Region: Annual Program Review. 2004; IPPF: Tunis.

- United Nations Population Fund. The Gap Exists Between Hopes and Realities. New York: UNFPA. At: <http://www.unfpa.org/intercenter/hopes/gap.htm>. Accessed 5 July 2006.

- World Health Organization. Unsafe Abortion: Global and Regional Estimates of the Incidence of Unsafe Abortion and Associated Mortality in 2000. 2004; WHO: Geneva.

- Population Council.S al-Hegazi, D Huntington. Experience with Clinical Training in Postabortion Care in Egypt: Improving Medical and Interpersonal skills. 1997; Population Council: Cairo.

- Global Health Council. Promises to Keep: The Toll of Unintended Pregnancy on Women in the Developing World. 2002; Global Health Council: Washington, DC. At: <http://www.globalhealth.org/assets/publications/PromisesToKeep.pdf>. Accessed 7 March 2006.

- S Zubaida. Law and Power in the Islamic World. 2005; I.B. Tauris & Co. Ltd.: London.

- BF Musallam. Sex and Society in Islam. 1983; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge.

- O Asman. Abortion in Islamic countries: legal and religious aspects. Medicine and Law. 23: 2004; 73–89.

- A Yusuf Ali. The Meaning of the Holy Qur'an. 2002; Armana Publications: Maryland.

- A Gürsoy. Abortion in Turkey: a matter of state, family, or individual decision. Social Science and Medicine. 24(4): 1996; 531–542.

- Al-Azhary Sonbol A. The Creation of the Medical Profession in Egypt during the Nineteenth Century: A Study in Modernization. Ph.D. dissertation. Georgetown University, Washington DC, 1981.

- A Sonbol. Women, the Family and Divorce Laws in Islamic History. 1996; Syracuse University Press: New York.

- International Planned Parenthood Foundation. Islam and Family Planning. 1974; IPPF: London.

- International Planned Parenthood Foundation. Unsafe Abortion and Sexual Health in the Arab World. 1992; IPPF: Damascus.

- FS Alkuraya, RA Kilani. Attitude of Saudi families affected with hemoglobinopathies towards prenatal screening and abortion and the influence of religious ruling (fatwa). Prenatal Diagnosis. 21: 2001; 448–451.

- BBC. Religion and Ethnics. Abortion: The Islamic View. At: <http://www.bbc.co.uk/religion/ethics/abortion/relig_islam1.shtml. >. Accessed 13 March 2005.

- Iran: the abortion bill. Hamshari Daily. 13 April 2005.

- International Women's Rights Action Watch. The Women's Watch. Vol.12, Nos.1/2, December 1998.

- Abortion issue in Egyptian spotlight. Arab News. 16 March 2004.

- C Chelala. Algeria abortion controversy highlights rape of war victims. Lancet. 351: 1998; 1413.

- P Ilkkaracan. Women and Sexuality in Muslim Societies. 2000; Women for Women's Human Rights and Women Living Under Muslim Laws.

- Annual Review of Population Laws. 2004; Harvard University. At: <http://annualreview.law.harvard.edu/annual_review.htm>. Accessed 7 July 2006.

- S Ebabdi. The Legal Punishment for Murdering One's Child: Seminar on the Rights of the Child. 2001; National Association in Support of Children's Rights in Iran: Tehran.

- Tunisian Action Plan. 1991; Tunisian Ministry of Health: Tunis.

- F Bejaoui. Avortement et droit penal. L Labidi. Médecine et Santé des Femmes. 1988; Hopital d'Enfants: Tunis, 32–37.

- Amended Tunisian abortion law. IPPF Medical Bulletin. 8(2): 1974; 4.

- Hessini L. Reproductive rights and women's status in Tunisia. Master's thesis. School of Public Health, University of Michigan, 1993.

- J Blum, S Hajri, H Chélli. The medical abortion experiences of married and unmarried women in Tunis, Tunisia. Contraception. 69: 2004; 63–69.

- A Bulut, N Toubia. Abortion services in two public sector hospitals in Istanbul, Turkey: how well do they meet women's needs?. AI Mundigo, C Indriso. Abortion in the Developing World. 1999; Zed Books: London, 259–278.

- S Lane, JM Jok, M El-Mouelhy. Buying safety: the economics of reproductive risk and abortion in Egypt. Social Science and Medicine. 47(8): 1998; 1089–1099.

- Iran's Guardian Council against abortion bill. IranMania. 1 May 2005.

- A Benabdellah. Avortement et statut de la femme en Islam. La Vie Economique. 18: 2002; 40–42.

- B Belkhodja. Avortement en Algérie Problématique et Prévention: Colloque National sur l'Avortement à Risque. 2005; Association Algérienne pour la Planification Familiale: Algiers, 1–7.

- A Akin, GO Kocoglu, L Akin. Study supports the introduction of early medical abortion in Turkey. Reproductive Health Matters. 13(26): 2005; 101–109.

- IPPF Arab World Region Annual Program Review. 2004; IPPF: Tunis.

- International Planned Parenthood Foundation. IPPF Annual Programme Review 2004–2005. 2006; IPPF: London.

- L Zahed, M Nabulsi, H Tamim. Attitudes towards prenatal diagnosis and termination of pregnancy among health professionals in Lebanon. Prenatal Diagnosis. 22: 2002; 880–886.

- Al-Azhar University, International Islamic Center for Population Studies and Research. International Conference on Population and Reproductive Health in the Muslim World. Final Report. 1998; Al-Azhar: Cairo.

- Egyptian Fertility Care Society, Population Council. Postabortion Caseload Study in Egyptian Public Sector Hospitals. 1997; Population Council: Cairo.

- Egyptian Fertility Care Society, Population Council. Scaling-up Improved Postabortion Care in Egypt: Introduction to University and Ministry of Health and Population Hospitals. 1997; Population Council: Cairo.

- Egyptian Fertility Care Society, Population Council. Cost-effectiveness of Postabortion Services in Egypt. 1998; Population Council: Cairo.

- Population Council. Counselling the Husbands of Postabortion Patients in Egypt: Effects on Husband Involvement, Patient Recovery and Contraceptive Use. 1997; Population Council: Cairo.

- Population Council. Management Support for Postabortion Operations Research at the Egyptian Fertility Care Society. 1998; Population Council: Cairo.

- Population Council. Lessons from introducing postabortion care in Egypt. Population Briefs. 10(3): 2004

- Planned Parenthood Federation of American-International. History of the Postabortion Care Program in Sudan. 2005; PPFA-I: Nairobi.

- Qui sommes-nous? Telquel, 28 janvier au 3 février, 2006.

- L Zahed, J Bou-Dames. Acceptance of first-trimester prenatal diagnosis for the haemoglobinopathies in Lebanon. Prenatal Diagnosis. 17: 1997; 423–428.

- A Seif El-Dawla, AA Hadi, NA Wahab. Women's wit over men's trade-offs and strategic accommodations in Egyptian women's reproductive lives. R Petchesky, K Judd. Negotiating Reproductive Rights. 1998; Zed Books: London.

- Avortement : autopsie d'un drame social 2006. Telquel. 18 au 24 février, 2006.

- D Huntington, L Nawar, D Abdel-Hady. Women's perceptions of abortion in Egypt. Reproductive Health Matters. 5(9): 1997; 101–108.

- LE Amado. Sexual and Bodily Right as Human Rights in the Middle East and North Africa. Workshop Report. 2004; Women for Women's Human Rights.

- Reproductive Health Matters, Arabic edition, No.5, 2002.