The last seven years have seen growing advocacy for male circumcision as a means of HIV prevention, commencing first among public health specialists working mainly in the USA, then among some of those working in international organisations, and more recently endorsed as part of a comprehensive package of measures supported by both the World Health Organization and UNAIDS.Citation1

Opinions continue to differ sharply as to whether or not to implement this form of preventionFootnote* – or how quickly to do so – although there appears to be growing consensus that, as with all HIV-related public health interventions, male circumcision must be promoted in a culturally appropriate, rights-based and gender sensitive way.Citation3

Papers and discussions elsewhere take up issues of gender sensitivity and rights. It is issues of culture and politics that I want to examine here. All over the world male circumcision has its roots deep in the structure of society. Far from being a simple technical act, even when performed in medical settings, it is a practice which carries with it a whole host of social meanings. Some of these meanings link to what it is to be a man, with circumcision taking place as a rite of passage into adulthood in several African and Oceanic societies.

In other settings, male circumcision carries religious connotations, it being widely practised among Jews and Muslims, although less so among Christians and rarely among other religions. From the late 19th century onwards, however, male circumcision also entered into the field of public health. It has been viewed in the USA in particular as a panacea for a wide range of medical and social problems historically – from paralyisis and hip joint disease to nervousness, anti-social behaviour and imbecility.Citation4

Crucially, however, male circumcision remains a potent indicator of hierarchy and social difference. During the Ottoman and Moorish Empires, in Nazi Germany, in India at partition and in the recent genocides of Bosnia and East Timor, a man's circumcision status had serious consequences for how he was treated: with violence, torture and death being the consequence for those who fell short of the mark.

Against this background, this paper seeks to add balance and context to current debates concerning male circumcision. It questions the value neutrality of an act so profound in its social significance and so rich in meaning. It highlights how male circumcision – like its counterpart female genital mutilation – is nearly always a strongly political act, enacted upon others by those with power, in the broader interests of a public good but with profound individual and social consequences.

A vast deal has been written on this subject by sociologists, anthropologists, historians and psychoanalysts, among others,Citation5 which I will only touch upon here, yet in its current global incarnation for HIV prevention, male circumcision is being talked of as if it were the most trivial and inconsequential of matters. “Just a little snip” was how one participant in one of the recent WHO/UNAIDS consultative meetings on male circumcision described it.

A most violent of histories

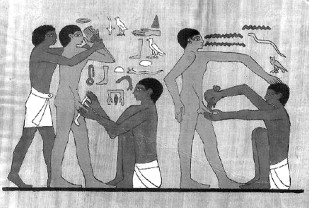

It is apocryphal to claim that the earliest records of male circumcision stem from the Egyptian sixth dynasty.Citation6 A bas relief on the sarcophagus of Ankh-ma-Hor at Saqqara purportedly shows male circumcision being practised as a ritual prior to entry into the priesthood ().Citation7 What is less often commented upon is the fact that in this same depiction of circumcision, far from participating willingly in the practice, one of the men at least appears to be being forcible restrained.

Figure 1 Ancient Egyptian relief, Ankhmahor, Saqqara, Egypt (2345–2182 BCE)Footnote*

Certainly, the practice of male circumcision has ancient origins. The Greek historian Herodotus recorded the practice in Egypt in 5th century BC, and in the Semitic tradition, male circumcision is linked to a covenant with God dating back to Abraham.

The Galatian controversy, as it is sometimes referred to, records early opposition to male circumcision, when the practice proved a hindrance to mass conversion to Christianity. Galatians 5:6 attempts to clarify the matter by says that “in Christ Jesus neither circumcision nor uncircumcision count for anything”. I Corinthians 7:18–20 goes further when it states: “Circumcision means nothing, and uncircumcision means nothing; what matters is keeping God's commandments”.

But was or is male circumcision a relatively minor procedure? Crucially, Jewish circumcision now differs markedly from the originally instituted covenant. Until 300 BC, the ritual is recorded as calling only for the removal of the tip of the foreskin. However, when Jewish athletes travelled to Greece to compete in athletic events, they imitated their Greek hosts by pulling their remaining foreskins over the glans penis and tying them closed with a ribbon or piece of string. Over time, this stretching is reported as resulting in a fully-functioning foreskin.

“When the athletes returned home, Jewish elders were incensed to see their Hellenised foreskins. To put an end to the practice, they instituted the periah, which involved not only the complete removal of the foreskin but the tearing of the frenulum [the delicate and sensitive membrane on the underside of the penis] with a sharpened fingernail.” Citation8

Other forms of religious male circumcision were no less damaging. As Sir Richard Burton notes in a footnote to the Arabian Nights:

“The varieties of circumcision are immense… probably none more terrible than that practised in the province of Al Asir… where it is called salkh (lit., scarification). The patient, usually from ten to twelve years-old, is placed upon raised ground holding in right hand a spear… The tribe stands about him to pass judgment on his fortitude and the barber performs the operation with the Jumbiyak dagger, sharp as a razor. First he makes a shallow cut, severing only the skin across the belly immediately below the navel, and similar incisions down each groin, then he tears off the epidermis from the cuts downwards and flays the testicles and penis, ending with amputation of the foreskin. Meanwhile, the spear must not tremble…” Citation9

What justification could be offered for such a violent practice? Opinions differ, although the 13th century Rabbi Moses Maimonides was of the view that:

“As regards to circumcision, I think that one of its objects is to limit sexual intercourse and to weaken the organ of generation as far as possible… Circumcision simply counteracts excessive lust: for there is no doubt that circumcision weakens the power of sexual excitement. Our sages say distinctly ‘It is hard for a woman, with whom an uncircumcised had sexual intercourse, to separate from him.’ This is, I believe, the best reason for the commandment [of circumcision].” Citation10

Male circumcision has also been a punishment inflicted upon those who were not circumcised. As Berkeley reports:

“More than two centuries ago, young Warren Hastings was forcibly circumcised. Along with three hundred of his fellow British workers in Cossimbazar, India, 24-year old Warren was stripped, sodomized, masturbated and publicly circumcised by Mogul troups who over-ran the British outpost. Warren watched in horror as his prepuce was carried away in a bag containing all three hundred freshly severed foreskins – trophies for the Moslem Moguls. Lanky effeminate Hastings, destined to become one of Britain's great colonial statesmen, wrote of his ordeal ‘I, myself, was carved’.” Citation11

The colonial explorer John Hanning Speke was circumcised on the field of battle during the search for the source of the Nile, when local Somali men overran the British encampment. An emotionally charged account reads:

“One of them shrieked, charging at Speke – Speke parried a sharp blow that snapped off the blade of his sword. Speke was in a daze when one of them, pressing a long knife to his throat. Lashed out ‘Circumcision or death, you Christian dog.’ He pulled Speke's foreskin and stretched it tight, then sliced it off with his razor edge blade.” Citation12

Such practices had ancient origins, it being reported that in Koranic times, the slashed prepuces of “unbelievers”, collected up following battle, were held as trophies of victory. In line with the martial code of the Moghul Empire, a warrior reportedly rose in rank according to the number of foreskins he brought in from the field.Citation13

Business dealings in the 17th century Moghul Court in India required men to be circumcised. Elihu Yale, the patron of Yale College and an early British trader, reportedly allowed the grand Moguls to circumcise him. His special envoys to the Mogul court were likewise circumcised. Sir Josiah Child, then Governor of the East India Company, sent two negotiators to the Moghul Court in 1686:

“We were received with our hands tied by a sash in front of us when the Grand Mogul escorted us into a private chamber where he ordered a eunuch to disrobe us. He proceeded to satisfy himself that we were both circumcised and therefore fitting spokesmen for an uncircumcised race. He ordered our hands be untied (and thereafter) treated us as honourable men.” Footnote*

Contested terrain

Male circumcision has always been contested terrain, with opinions differing sharply as to its aesthetic, social and other benefits. For the ancient Greeks, for example, there was nothing wrong with male nudity in their games save that the foreskin had to be tied tight with a clasp or fibula – as can be seen on numerous ancient vases and friezes. In 168 BC, the Seleucid Emperor Antiochus IV outlawed circumcision. Mothers who had their infants ritually circumcised were to be flogged, crucified or stoned. In AD 70, the Roman Emperor Vesperian instituted a circumcision tax known as the Fiscus Judaicus and reportedly required every man to be inspected.

Yet in later years, male circumcision was to be promoted for its “health-promoting” value and its capacity to reduce moral ills. The explorer Sir Richard Burton wrote the “saving rite of circumcision” is one of the “thousand external functions compensating for moral delinquencies”.Citation14 Berkeley cites one Dr Rae, writing in India a century earlier, as saying: ‘My Muslim assistant tells me that Moorish boys are addicted to violent self-abuse till they be circumcised, whereupon they are temper'd to natural Venery”.Citation15

Inspired both by these ideas and by the very real fear that uncircumcised men might be forcibly circumcised in battle, in 1661 the British Governor of India and the Council of Madras ordered that all “cadets shall be bodily examined… If a cadet could not strip his yard, [the company doctor shall] clip the skin entire”.Citation16 The Old London Company reportedly kept records of the circumcision status of employees. And in the 19th century, British Royalty began to circumcise their male heirs, creating both a trend and a social status difference in this respect. By the start of World War II, an estimated 80% of upper class males in the UK were circumcised compared with 50% of working class men.Footnote†

A deeply political act

But male circumcision has always been a deeply political act – either on the grand scale (and what does this reveal about current advocacy by Northern countries for its “rolling out” across so many African nations?) or at more local level. During the Turkish occupation and subsequent genocide in Armenia in 1915, during which some 1.5 million died, Armenian men and boys were forcibly circumcised. In Nazi Germany, a man's circumcision status often determined whether he was deported to a concentration camp or not. In the 1930s and again in the 1980s as part of national revivalism, male circumcision was banned in Bulgaria because of its connotations with the earlier Turkish occupation of the country.

Moreover, even in the USA today there exists much controversy over the practice. On 8 January 2007, a Bill was submitted by a coalition of interest groups to the US Congress and 16 state legislatures, entitled the Federal Prohibition of Genital Mutilation Act of 2007.Citation17 This seeks to amend the earlier enacted Female Genital Mutilation Act of 1996 so that boys, intersex individuals and non-consenting adults may also be protected from genital mutilation.

The Bill proposes to increase the maximum punishment of offence to 14 years imprisonment, to include assistance or facilitation of genital mutilation of children or non-consenting adults as an offence, and prohibit persons in the USA from arranging or facilitating genital mutilation of children and non-consenting adults in foreign countries. While it will take time for the Bill to be considered at the highest levels of national government, it reached committee stage on 4 April 2007 in the State of Massachusetts.Citation18

Among the support offered for the Bill is evidence of physical and psychological damage. Immediate physical complications resulting from male circumcision include pain, shock, haemorrhage, infection, excessive skin loss and injury to adjacent tissue. Haemorrhage and infection can occasionally cause death even when the procedure is carried out in medical conditions. Long-term negative consequences include loss of sexual sensitivity, and increased friction and pain during sexual intercourse. Psychological damage includes feelings of anger, incompleteness, anxiety, depression, and psychological trauma.

Similar complications have been noted in developing country settings. Bonner cites a prospective study which finds a complication rate of 11.2% among circumcisions performed in hospitals in Kenya and Uganda.Citation19 Nearly 3% of patients suffered wound infection; the next most common complications were severe haemorrhage(1.2%), retention of urine (1.2%) and penile oedema (1.2%). Complications rates from non-medically performed circumcisions are typically much higher and include mutilation, penis loss and even death.Citation20

A remedy for all ills?

So what does this brief review reveal so far? First and foremost, male circumcision is an act linked to deep-seated beliefs and ideologies about the social order. It is by no means a simple prevention technology. Male circumcision is almost inevitably linked to the expression of power – be this intra-group, between old and young for example, or inter-group in nature. Its links both with colonialism and with resistance to colonialism, invasion and conquest are profound, as are its connections with overtly moral codes and conventions. Finally, far from being a trivial or routine operation, male circumcision is an act that has profound social connotations and long-lasting physical and psychological consequences. A recent report in the internet journal Africa Update makes this point when it says:

“Male circumcision is often thought to purify and protect the next generation from dangerous outside influences, to bind all youth to their peers or age set. As part of intensive group socialization, it also firmly establishes age set relationships, generational respect and authority patterns .”Citation21 (emphasis added)

This is one reason why male circumcision is so important, and one reason why opinions are so heated about it.

In the 1870s, Lewis Sayre, a leading US orthopaedic surgeon, claimed he was successful in using male circumcision to cure paralysis and hip-joint disease, and to “quiet nervous irritability”. He later extended his treatment to hernia and stricture of the bladder. In 1875 he wrote, “‘peripheral irritation’ from the foreskin sometimes caused an ‘insanity of the muscles’ in which a victim's muscles acted ‘on their own account, involuntarily without the controlling power of the person's brain’”.Citation22

Just a few years later in 1882 George Beard claimed that:

“Persons who are very sensitive nervously, and especially Americans, living in our American climate, are liable to develop all or many of the symptoms of sexual neurasthenia… a temperament previously made assertive by exhausting climate, work, worry, tobacco and alcohol.” Citation23

Circumcision was the solution. In 1891, Peter Remondino wrote:

“The prepuce seems to exert a malign influence in the most distant and apparently unconnected manner; where, like some evil genii or sprites in the Arabian tales, it can reach from afar the object of its malignity, striking him down unawares in the most unaccountable manner; making him a victim to all manner of ills, sufferings and tribulations; unfitting him for marriage or the cares of business; making him miserable and an object of scolding in childhood… beginning to affect him with all kinds of physical distortions and ailments, nocturnal pollutions, and other conditions… calculated to weaken him physically, mentally and morally; to land him, perchance, in jail or even in a lunatic asylum.” Citation24

In 1894, B Merrill Ricketts identified an astounding array of maladies that could be cured through male circumcision.Citation25 They included eczema, oedema, elephantiasis, gangrene, tuberculosis, hip-joint disease, enuresis, general nervousness, impotence, convulsions and hystero-epilepsy.

Male circumcision for curative purposes has had many advocates and adherents. John Kellogg, the founder of the Kellogg's cereals empire in the USA, viewed it as an effective cure for masturbation and the social ills that were said to accompany it. He advocated an unashamedly punitive approach:

“A remedy which is almost always successful in small boys is circumcision. The operation should be performed by a surgeon without administering an anesthetic, as the brief pain attending the operation will have a salutary effect upon the mind, especially if it be connected with the idea of punishment.” Citation26

The social character of the public health argument

It has frequently been claimed that male circumcision offers protection against sexually transmitted infections for men, especially in developing countries. Yet in precisely these settings, few if any investigations contain robust controls for confounding factors such as social background, sexual behaviour or penile hygiene. Most usually the studies cited report on small and adventitious samples of men attending STI or HIV clinics.

In richer world settings, where well-designed, population-based studies have been conducted, the evidence is weak, to put it mildly. The US 1992 National Health and Lifestyle Survey, for example, reported: “with respect to STDs we found no evidence of a prophylactic role for circumcision and a slight tendency in the opposite direction”.Citation27 And a recent UK study reported:

“We did not find any significant differences in the proportion of circumcised and uncircumcised British men reporting ever being diagnosed with any STI (11.1% compared with 10.8%, p =0.815), bacterial STIs (6.4% cf 5.9%, p =0.628), or viral STIs (4.7% cf 4.5%, p =0.786)... We also found no significant associations between circumcision and being diagnosed with any one of the seven specific STIs.” Citation28

Moreover, and at the same time as there are calls for a radical scaling-up of male circumcision throughout Africa, the:

“… circumcision experiment has already been performed in the United States. How successful has it been? With the highest rate of circumcision (in the developed world), the USA also has higher rates of infant mortality and shorter male life-expectancy than similar developed nations; the highest rates of sexually transmitted diseases of any developed nation; the highest rates (by far) of heterosexually transmitted HIV infection of any developed nation; and rates of cervical and penile cancer that are similar to those of other developed nations.Yet these are the very diseases that circumcision has been touted as a sure preventive for: any impartial observer must conclude that the century-long experiment has failed.” Citation29

Conclusions

How can we best understand contemporary advocacy of male circumcision as a prophylactic intervention? Some of the factors that are likely to be at work, without doubt, tie to the complex interfaces between individual intervention and social hygiene, and between public health and social control.

The last few years have seen growing impatience on the part of national programmes, international agencies and public health experts to make headway against the global HIV epidemic. In some circumstances, it has been claimed that primary prevention based on an educational, social and rights-based response has failed, and that what is needed is a more thoroughgoing engagement with the principles of ‘traditional’ public health medicine.

Both in academic journals and in the corridors of international HIV conferences, colleagues murmur that the time has come for “biomedical prevention” – the roll-out of antiretroviral drugs to otherwise healthy populations of sex workers and other vulnerable groups is but one illustration of such an approach. The 2007 International AIDS Society Sydney conference on HIV Pathogenesis, Treatment and Prevention has a track focused on the theme of Biomedical Prevention. It is within this context that current advocacy for male circumcision must be understood.

But there are other forces at work. Some of these have their origins in the needs of national authorities and community groups to find answers to the seemingly relentless growth of HIV. Others have their origins in the willingness of these same groups to embrace solutions which attract funds – in this case from USAID and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation – major funders of HIV prevention which have publicly endorsed male circumcision as an HIV prevention strategy. Other donors have been more cautious. Perhaps more deeply seated, sources of impetus have their origins in the “joined up” approach to HIV prevention that male circumcision appears to offer. Not only does circumcision appear to offer a modern day public health solution, but it also carries with it a moral authority that seems difficult to deny.

In both the historical accounts examined in this paper and in their modern-day counterparts, there is a strident insistence both on the virtue of the act and its potential to effect change. Some have gone so far as to claim that it would be morally unethical not to offer male circumcision within the present context. But in both the past and recent present, the evidence base for the acceptability and prophylactic effectiveness of male circumcision remains to be tested through scale-up. Evidence from recent trials, which at the very least requires continued scientific scrutiny, is now trumpeted as “truth”. Opponents, and those who doubt the effectiveness at population-level of male circumcision in the absence of major changes in sexual practice, have been silenced and marginalised under the onslaught. Curious alliances have arisen between clinicians, advocates, religious leaders and moral entrepreneurs.

Perhaps most serious is the capacity of male circumcision advocacy to open up new divisions both nationally and internationally. While in Kenya recently, I was told that it would be unthinkable for that nation to have an ‘uncircumcised President’. In that same country, uncircumcised boys have reportedly been sent home from school until they have the operation.Citation29 In the gossip that has surrounded recent WHO/UNAIDS consultations on the subject, both sides described the other as “irrational”, “guided by ideology” and “unscientific”.

At the very moment when two decades of programming and advocacy are making headway against HIV-related stigma and discrimination, we run the risk of creating new physical and social differences around which division can solidify – between the circumcised and those who are not; between those who advocate for male circumcision and those who do not; and between those who favour a broad-based and comprehensive response and those who still search for seemingly simpler solutions.

Notes

* The Brazilian government took a recent decision not to promote male circumcision as an HIV prevention measure, and the President of Uganda has rejected male circumcision as an appropriate form of HIV prevention.Citation2

* Cited in Berkeley.Citation11

† Cited in Berkeley.Citation16

References

- See <http://data.unaids.org/pub/PressRelease/2007/20070328_pr_mc_recommendations_en.pdf>. Accessed 1 April 2007.

- See <http://vivirlatino.com/2007/04/03/brazil-says-no-to-circumcision.php> and <www.circumcisionandhiv.com/2007/03/ugandan_preside.html>. Accessed 1 April 2007.

- See, for example, Sawires S, Dworkin S, Coates T. Male Circumcision and HIV AIDS: Opportunities and Challenges. 2006. At: <www.aidsvaccineclearinghouse.org/MC/circumcision_paper_sawires_dworkin_coates.pdf>. Accessed 1 April 2007.

- For recent reviews, see Gollaher D. Circumcision. New York: Basic Books, 2000.

- See also Darby R. A Surgical Temptation. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2005.

- See, for example, the recent UNAIDS feature story on male circumcision at <www.unaids.org/en/MediaCentre/PressMaterials/FeatureStory/20070226_MC_pt1.asp>. Accessed 1 April 2007.

- At: <www.philae.nu/akhet/Saqqara11.html>. Accessed 1 April 2007.

- Cited in Griffin G. Decircumcision. San Francisco: Added Dimensions Publishers, 1992. p.17.

- Footnote 180. At: <www.wollamshram.ca/1001/Sn_2/v12notes.htm>.

- Maimonides Rabbi. A Guide for the Perplexed (trans. M. Friedlander). 1956; Dover: New York.

- B Berkeley. Foreskin – A Closer Look. 1993; Alyson Publications: Boston, 51.

- Edwardes Allen. Death Rides a Camel. A Biography of Sir Richard Burton. 1983; Julian Press: London. Cited at: <www.circlist.com/rites/british.html>.

- Edwardes Allen. The Jewel in the Lotus: A historical survey of the sexual culture of the east. 1959; Julian Press: New York.

- R Burton. The Jew, The Gypsy, and El Islam. 1874; Hutchinson and Co: London, 67–71.

- B Berkeley. Circumcision: the ultimate anti-masturbation strategy. 1993. At: <www.solotouch.com/res.php?t=a&num=33. >.

- See <www.circlist.com/rites/british.html>. Accessed 1 April 2007.

- See <www.mgmbill.org/index.htm>. Accessed 5 April 2007.

- See <www.mgmbill.org/mamgmbillstatus.htm#current>.

- GAO Magoha. Circumcision in various Nigerian and Kenyan hospitals. East African Medical Journal. 76(10): 1999; 583–586. Cited in: Bonner K. Male circumcision as an HIV control strategy: not a “natural condom”. Reproductive Health Matters 2001;9(18):143–55.

- P Sidley. Botched circumcisions kill 14 boys in a month [News roundup]. BMJ. 333(8 July): 2006; 62.

- Africa Update. At: <www.ccsu.edu/Afstudy/upd3-2.html>.

- LA Sayre. Circumcision versus epilepsy, etc. Medical Record (New York). 5: 1870–71; 233–234.

- GM Beard. Nervous Diseases Connected with the Male Genital Function. Medical Record (New York). 22: 1882; 617–621.

- PC Remondino. History of Circumcision from the Earliest Times to the Present: Moral and physical reasons for its performance. 1891; FA Davis: Philadelphia, 254–255.

- B Merrill Ricketts. The last fifty of a series of two hundred circumcisions. New York Medical Journal. 59: 1894; 431–432.

- J Kellogg. Treatment for Self-Abuse and its Effects. Plain Facts for Young and Old. 1888; F Segner & Co: Burlington, Iowa, 295.

- E Laumann, C Masi, E Zuckerman. Circumcision in the United States. Prevalence, prophylactic effects, and sexual practice. Journal of the American Medical Association. 277(13): 1997; 1052–1057.

- SS Dave, AM Johnson, KA Fenton. Male circumcision in Britain: findings from a national probability sample survey. Sexually Transmitted Infections. 79: 2003; 499–500.

- R Darby. The sorcerer's apprentice: why can't the United States stop circumcising boys?. 2005. At: <www.historyofcircumcision.net/index.php?option=content&task=view&id=61. >. Accessed 1 April 2007.