Abstract

Abortion in Burkina Faso is a subject that neither abortion providers nor women want to talk about. Abortion providers fear criminal prosecution; women’s silence is dictated more by the wish to avoid the stigma of a “shameful” pregnancy. Qualitative investigations in Burkina Faso among 13 key informants in a rural village in 2000 and 30 women and men aware of experience of abortion in the capital Ouagadougou in 2001, explored two paradoxes: what prompts women and providers to reveal something they want to be kept totally secret, and how do women keep their abortion secret while nevertheless talking to others about it? The study found that young women in Burkina Faso are impelled to talk to their boyfriends, friends and in fewer cases women relatives about their unplanned pregnancy, first to decide to have an abortion and then to get help in finding a clandestine provider. Abortion is also kept secret because it is a subject on which there is no social consensus, alongside extra-marital sexual activity, contraceptive use by young people and out-of-wedlock pregnancies. The key to keeping a secret lies in the choice of those with whom to share it; good confidants are those who are bound by secrecy through the bonds of intimacy or shared transgression.

Résumé

Au Burkina Faso, l’avortement est une question dont ni les prestataires de services d’avortement ni les femmes ne souhaitent parler. Les premiers craignent des poursuites pénales, le silence des femmes étant davantage dicté par la volonté d’éviter les stigmates d’une grossesse « honteuse ». Des enquêtes qualitatives au Burkina Faso auprès de 13 informateurs clés dans un village en 2000 et auprès de 30 femmes et hommes ayant connaissance de l’avortement dans la capitale, Ouagadougou, en 2001 ont étudié deux paradoxes: qu’est-ce qui pousse les femmes et les prestataires à révéler quelque chose qu’ils ne veulent absolument pas ébruiter, et comment les femmes gardent-elles le secret sur leur avortement, tout en en parlant à d’autres ? L’étude a montré que les jeunes femmes au Burkina Faso ressentent le besoin de parler à leurs partenaires, leurs amies et, moins souvent, à leurs parentes de leur grossesse non désirée, d’abord pour décider d’avorter et ensuite pour trouver un praticien clandestin. L’avortement est également tenu secret car il ne fait pas l’objet d’un consensus social, comme l’activité sexuelle extraconjugale, l’utilisation de contraceptifs par les jeunes et les grossesses hors mariage. La clé pour garder le secret réside dans le choix de ceux avec qui le partager, les bons confidents étant ceux qui sont tenus au secret par des liens d’intimité ou de transgression commune.

Resumen

El aborto en Burkina Faso es un tema del cual ni las mujeres ni los prestadores de servicios quieren hablar: estos últimos por temor a una acción judicial; las mujeres, por evitar el estigma de un embarazo “vergonzoso”. Las investigaciones cualitativas en Burkina Faso entre 13 informantes clave de un poblado rural, en el año 2000, y 30 mujeres y hombres con conocimiento de aborto en la capital de Ouagadougou, en 2001, exploraron dos paradojas: qué induce a las mujeres y los prestadores de servicios a revelar algo que desean mantener totalmente en secreto, y cómo guardan las mujeres su secreto de aborto aunque hablen con otros al respecto? El estudio encontró que las mujeres jóvenes en Burkina Faso se sienten impelidas a hablar con sus novios, amigas y, en algunos casos, parientes del sexo masculino, sobre su embarazo no planeado, primero para decidir tener un aborto y después para conseguir ayuda para encontrar un prestador de servicios clandestino. Además, guardan el secreto del aborto porque éste es un tema respecto al cual no existe consenso social, al igual que la actividad sexual extramatrimonial, el uso de anticonceptivos por la juventud y los embarazos fuera del matrimonio. La clave para guardar un secreto yace en la elección de las personas con quienes se comparte; los buenos confidentes son aquéllos que se sienten obligados a guardar el secreto por los lazos de una relación intima o de una transgresión compartida.

Abortion in Burkina Faso is a subject that neither abortion providers nor women want to talk about. Abortion providers fear criminal prosecution, since induced abortion is illegal in Burkina Faso, as in all of West Africa.Citation1 In Burkina Faso, abortion is permitted only in cases of incest, rape, when the woman’s life is at risk or in cases of fetal malformation. The law is applied with some leniency, however, and women having clandestine abortions are seldom prosecuted. Women’s silence is dictated more by the wish to avoid the stigma of a “shameful” pregnancy. In traditional forms of social organisation in Africa, fertility is prized,Citation2Citation3 and all pregnancies are welcomed. Married couples have no reason to prevent or terminate a pregnancy. The only unwanted pregnancies are those that occur outside normative sexual activity, e.g. pre-marital pregnancies. The expression “unwanted pregnancy” is unknown in the local languages of West Africa, but the concept of “shameful pregnancies” exists for those arising from uncondoned sexual relations. Abortion is shameful by association with a shameful pregnancy, since it reveals – by concealing – the contravention of sexual norms.Citation4–6

Qualitative investigations in Burkina Faso, both in a rural setting and in the capital Ouagadougou, showed that people talk a lot about abortion under the cover of secrecy. This discovery enabled some colleagues and I to design a new method of gathering quantitative data on abortion in the context of clandestinity, which we called the confidants’ method.Citation7 We asked respondents in a general population survey to list women of reproductive age to whom they were close. These respondents were then asked if their female friends had had any abortions in the years preceding the survey, what method was used, whether they experienced complications and whether they went to a hospital. Applying this method in Ouagadougou in 2001, we found a high abortion rate, 40 abortions per 1000 women aged 15–49, especially among young, unmarried girls. Similar results have been found in other capitals of West Africa.Citation8–11

Sociological theories of secrecy

Early theorists defined secrets as both the enablers and the consequences of deviancy, transgression and evasion, and the shaping principle of the opposite of law and order. “Secrecy provides a cloak behind which forbidden acts, legal violations, evasion of responsibility, inefficiency, and corruption are concealed.” As such, the secret is the expression of moral badness.Citation12 But it is simplistic to see the secrecy surrounding abortion as resulting from the (multi)transgressive nature of the act.

More recent theorists argue that secrets can better be understood as the product of conflicts of interest between individuals and groups, and between values. Thus, opposition to dominant social norms can generate secrets, and any nexus between social groups with diverging interests may give rise to secrets, such as competition between laboratories. Ultimately, secrets result from the confrontational and contradictory nature of social systems, which are beset with contradictions.Citation13 Keeping a secret is a strategy used by individuals whose actions are constrained by conflictive, socially enforced decision-making. Secrecy allows an individual to remain within the established social order. The disjunction between words and deeds is not merely a matter of hypocrisy, but results from the complex latticework of belonging to different social circles with conflicting values and behaviours. Although people have secrets, they share their secret with others in the same situation as them, while hiding it from others. Paradoxically, then, secrets are shared information,Citation14 and secrecy can only ever be partial.

Rapid changes in the formation of first unions are currently a source of conflict between young and old, men and women in Burkina Faso.Citation15Citation16 Whereas today’s young West Africans, especially urban dwellers, aspire to a chosen union based on love and engage in pre-marital sexual activity, their families still continue to place a higher premium on marital fertility and try to control young women’s sexual activity. These tensions are resolved by individuals through abortion in the case of pre-marital pregnancy, and keeping the abortion secret.

This article explores two paradoxes related to the circulation of information about abortion in Burkina Faso: 1) what prompts women and providers to reveal something they want to be kept totally secret, and 2) how do women manage to keep their abortion secret while nevertheless talking to others about it? It examines the choice of confidants with whom young women share their abortion secret, the probability of leaks and the extent of gossip that exists in a rural and urban social environment.

Methodology

The author collected qualitative data on access to abortion services in two sites in Burkina Faso: a village about 25 km from Ouagadougou in 2000 and in Ouagadougou in 2001. The village study aimed to identify abortion providers and the abortion methods they used; 13 key informants were identified after four months of preliminary participant observation. The informants, both men and women, varied widely in terms of age and neighbourhood of residence: they included personal contacts with whom I or my colleague had built relations of trust, a village birth attendant, a traditional healer, a nurse, a birth attendant and an assistant at the nearest dispensary, two community health agents and a market drug seller. In informal conversations, only two of these informants disclosed that their girlfriend or wife had had abortions; all the others said they only knew of cases of abortion or had dealt with abortions in the course of their professional duties. These conversations were written up in ethnographic field notes.

The Ouagadougou study aimed to discover the involvement of social networks in the abortion process. 30 individual, semi-structured interviews were carried out by four assistants (three men and one women) with informants of both sexes and different ages living in two contrasting urban districts. Informants were recruited using the snowball technique, starting with a few respondents who we met while organising focus group discussions on birth control in the outskirts of town and with contacts of one of the interview assistants in the centre of town. Interviewers looked for respondents who agreed to talk about the abortion stories they knew of, whether their own or those of close friends or relatives. Of the 37 reported abortion stories, six were the respondents’ own abortion. Fifteen of the 30 respondents were women. Four were or had been married. Their ages ranged from 15 to 40, with 23 of 30 respondents aged 20–29. Their stories were noted down during the interview and typed up.

Sharing the secret to make the decision for abortion

In most cases of abortion reported to us in Ouagadougou, the unintendedly pregnant woman first talked about it with her partner. Mamadou, a young, unemployed, single man with no immediate marriage plans, had sexual relations with a young girlfriend from the same social circle. They took precautions against pregnancy by practising periodic abstinence. When the girl fell pregnant, she first broached the matter with him:

“It’s them, the girls, that create the problems for us; [my girlfriend] first told me that there was no risk, that she’d counted properly. And now, after a month, she comes and tells me that [her period] hasn’t come.” (Age 26, single, informal settlement, unemployed, educated to 3rd year primary school)

If the couple agree that she should get an abortion, the young man usually remains involved. Thus, Bougma, a young, unemployed man also living in an informal settlement of Ouagadougou, was furious to learn of his girlfriend’s pregnancy; she apparently wanted to start a family, when he did not. This prompted a dispute. When she asked him for money for antenatal consultations, he refused. Faced with his unwillingness to become a father, she eventually gave in, and agreed to an abortion. Bougma then actively helped her to find an abortion provider:

“Her falling pregnant messed it all up; I can’t even ask somebody for five francs… And then we started fighting. We didn’t talk to each other for a month. Then she wanted me to give her money for a check-up, being weighed, getting medicines, all that. Where am I going to get that money? So she decided to get an abortion.” (Age 23, single, living in an informal settlement, unemployed, no formal education)

In other cases, the partners cannot agree on what to do about the pregnancy; the decision to get an abortion is then taken unilaterally by the woman. The man tends to have no involvement in the abortion process. Farida’s niece had an older, married lover with whom she was clearly not contemplating marriage. Falling pregnant by him seemed to her the worst-case scenario. Her parents were unaware of the relationship. The man did not want her to have an abortion. The quarrel turned violent; the young woman fled, took her decision alone and looked for help in getting the abortion:

“It seems that [my niece] collapsed in tears when she realised the situation she was in; she knew that she would be beaten [by her parents]. She went to see the man, who was already married… but he didn’t want her to get an abortion, and even threatened to kill her if she tried to get one. So she ran away to her big sister who lives here in Ouagadougou, and she decided to help her get an abortion.” (Farida, age 25, married, living in an informal settlement, housewife)

A woman who knows that her boyfriend will not agree to her having an abortion, and has the means to arrange matters alone, may decide not to tell him: the partner will then never share the abortion secret. So Darlene, a smart young woman from the town centre with a white-collar job and some resources, has girlfriends who do not always tell their partner when confronted with an unplanned pregnancy:

Q: Why do [your friends] not tell their boyfriends?

A: Because if a man gets you pregnant nowadays, he’s never going to tell you to get an abortion… You get one without telling him. All he’ll notice is that you’re sick, that’s all.” (Darlene, age 25, single, living in the city centre, secretary)

Most often, one or more people are consulted as well as (or instead of) the partner on the abortion decision. These will usually be the young woman’s girlfriends (sometimes her partner’s

friends if he is involved in deciding what to do) or one of her close relatives, typically her sister or mother. Peer involvement seems to play a mediating role in the couple’s relationship. When the girlfriend of one of Aboubacar’s close friends fell pregnant, for example, she went to him rather than her boyfriend and asked him to break the news to her partner. Aboubacar (age 22, single, living in the city centre, student) did so, and the two partners agreed she should get an abortion.The involvement of women relatives remains fairly uncommon. Young women with their own resources, especially a network of experienced and resourceful girlfriends, tend not to talk about the pregnancy to close women relatives, even when discussion with the partner is difficult or he decamps. When called upon, however, a young woman’s relative(s) often play a key role in the abortion decision-making process, sometimes to the point of supplanting the partner, especially when the couple lack resources or the girl has to deal with her plight alone. Martine, a water saleswoman living in the city centre, told of her young neighbour, who was going out with a boy from school and became pregnant. The couple had no resources so they turned to the girl’s mother, who took matters in hand:

“The boyfriend wanted her to get an abortion, because he was still at school, too… They talked to the girl’s mother. She called the boy in. He acknowledged the pregnancy. But he told the mother he was going to get the girl to abort it. The mother agreed.” (Martine, age 20, single)

Involving others to find an abortion provider and money to pay

Once the abortion decision has been taken, the woman (or couple) face finding an abortionist or an abortifacient by word of mouth. Clandestine abortion services do not advertise themselves, and the impermanence of these services (abortionists disappear, relocate, retire or die) complicates matters.Citation17 Most of our interviewees, while demonstrably quite knowledgeable about the methods of abortion available, did not know who to go to for a termination. This compels them to let the secret out. In order to carry out the act, which must remain clandestine, they have to speak of it. Both rural and urban women and couples asked their friends or relatives to help them find and access these services.

It is clear from the abortion narratives of the Ouagalese interviewees that abortion-seekers seldom manage to procure an abortion by random approaches to traditional practitioners or health personnel who are unknown to them. The network operates by sequential connections. Only where the health worker or healer is a friend or relative can the abortion-seeker dispense with an intermediary. So, Alizetta, age 15, a schoolgirl living in Ouagadougou city centre, tells how her cousin and her boyfriend were able to access an abortion directly through a friend who was a gynaecologist.

In the great majority of cases, it was the couple’s friends who were asked to help find an abortionist, as Mamadou described:

“She started with the tablets [nivaquine], but she was afraid, because they were too bitter, she didn’t want to take them, so she let it go until a month and a half. I gave her 2,500F for the roots, but again nothing happened. Her girlfriend took her to another healer, they paid 6,000F that I gave her back afterwards. She told me she felt it was going to drop, so that was OK, but then nothing. So she was now two months and a few days gone. So I could see that if something drastic wasn’t done, things could well get bad. So I told my mechanic mate about it, and he talked to some friends and they pointed him to the health worker at Lafitenga. They took him there so he could see where it was for me, and two days later him, the girl and me, we went there around 3pm, but the guy only works at night… so we had to wait until 11pm before we could go in, and you know how much that cost me? 15,000 flaming francs.”

Mamadou’s narrative highlights several features of access to clandestine abortion services in Ouagadougou. Repeated attempts may be needed to procure a termination of pregnancy. The failure of a first, and even a second attempt, forces the abortion-seeker to make a larger number of people privy to the secret. The secret is often restricted to a female group at the start of the search for an abortion, except for the partner, and tends to cross that boundary and involve other men when the search for an abortionist is not successful.

After a provider is found, the young woman needs to find the money to pay for the abortion. The cost may range from a few thousand CFA francs for traditional potions or abortifacients of varying effectiveness, tens of thousands for an injection by a health worker, and up to 100,000 or even 200,000 CFA francs for a curettage in hygienic conditions. Given that the monthly wage for a maid or caretaker is 20,000–40,000 CFA francs, an abortion using a medically safe method (even in unhygienic conditions) is beyond the reach of the poorest population groups. In villages, where the main source of income is the sale of agricultural produce, individuals have little ready cash. Abortionists – even those using medically safe methods – charge no more than 10,000 CFA francs. While finding that much money is no small matter, our research shows that fundraising does not entail breaking the seal of secrecy. In most cases, the young women will ask older relatives (and the partner, even if he is not privy to the secret) for money using a fabricated excuse. Financial emergencies are common in Burkina Faso, and any illness is likely to create this kind of demand. Young men also collect money from their close friends on the basis of a reciprocal obligation to help in return when the friend is in need.

Protecting the abortion secret through bonds of trust or shared transgression

We showed above that while information about abortion is quite widespread in Burkina Faso, the abortion secret circulates only within highly specific and defined sections of a couple’s social network.Citation13Citation14 The question is: why is it mainly other women, and especially close friends, who are informed, and what are the mechanisms that protect the abortion secret?

The easiest way to protect a secret is to confide it only to an intimate friend or relative who will protect personal information and not spread it to people outside that relationship.Citation18 Swapping secrets and intimate information contributes to forging bonds of trust. Mere acquaintances do not engage in self-disclosure.Citation19 This protection mechanism explains why women looking for an abortion in Burkina mainly tell other women, rather than men, and only peers where possible. These are the two categories of individuals with whom they are most likely to be on intimate terms. Such reciprocity is only possible between individuals in similar positions.

Another protection strategy is to talk only to those who are guilty of the same transgression. The parties will then be bound to one another by the knowledge of their mutual secret. Thus, “the conspirators… are entirely in one another’s hands, and the more dangerous the secret, the more total the dependency”.Citation14 In the case of clandestine abortion, these are women who have already had an abortion themselves. Shared transgression with the woman whose abortion they have caused is the key to the security clandestine abortion providers need in particular. It is in all women’s interests to conceal the name of their abortionist: admitting to knowing an abortionist is tantamount to self-incrimination or incriminating a close friend or relative who has had an abortion.

Another means of protection for providers is filtering. Abortionists take care not to accept women as patients who are not spoken for. Sécou, a young hairdresser with many female conquests in his village, was turned away by an abortionist he had approached when one of his girlfriends fell pregnant. He had asked around his circle of friends and was told that abortions were done at a particular clinic. One of our key informants, a former employee of the clinic, gave us a detailed account of abortions carried out there, which we cross-checked with other sources. But their “specialisation” was known in the village only to those who had used this service themselves. Sécou did not have the right connections, i.e. someone trusted by the male nurse who would guarantee Sécou’s silence afterwards, so the nurse did not admit that he performed abortions. The nurse’s intuition was right, in fact, because the hairdresser was one of the two young men in the village to talk openly to us about his partners’ abortions, respecting neither their nor the provider’s secret.

Where the abortion provider is a nurse or doctor, whether in the village or city, this filtering role often seems to be played by a subordinate health worker. Corruption probably plays a part in protecting the provider’s secret here, as subordinates are likely to get part of the abortion fee. Traditional abortion providers seem to rely less on this than on the fear that their “magical powers” inspires in their patients. For example, Karim, a medicine seller whose wife aborted after a visit to a traditional abortionist that had been arranged by a woman friend of hers, was incensed to find her writhing in agony with complications, having not even been told she was pregnant. Enraged, he sought vengeance. But, fearing the traditional practitioner’s powers, he consulted another healer for a solution. That healer provided him with medicine to treat his wife, and shrewdly took steps to protect his profession and his colleague by warning Karim that his wife would recover only if Karim did not try to exact vengeance, otherwise Karim would die.

Leaks and espionage

The security systems put in place by women and providers may be breached by both leaks and espionage. A leak can occur when a confidante or other person approached in the quest for an abortionist breaks the trust placed in them, whether motivated by benign or malicious considerations. Or the secret may inadvertently be leaked during a conversation or an argument, or deliberately from malice.

Of course, the more powerful a person is, the more leverage they have over others (such as the traditional practitioner above), and the more those others will refrain from leaking information for fear of reprisals, or simply to preserve existing good relations. In the same vein, the probability of leakage is relative to the number of people in the know; the more resource-strapped the abortion seeker, the greater that number tends to be. Power is thus associated with being able to avoid the secret getting out.

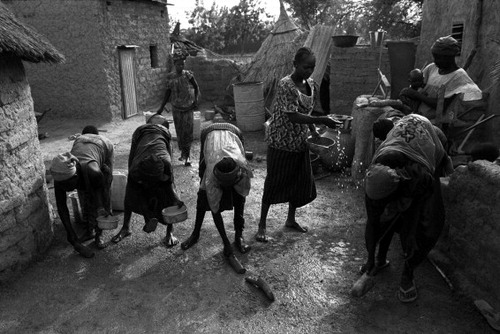

Secrets may also be disclosed by spying (or accidental observation). There are many problems with trying to keep a secret in a small community, where there is little assured privacy.Citation14 So, in rural Burkina, any movement, conversation or action is easily observed or overheard. The villagers live in the open air, retiring to their huts only to sleep; the same living space is shared by many people; the compounds are surrounded by relatively low mud walls and grouped together; and the savannah landscape is flat and bare. It may only be possible to escape the public gaze when the crops are high and shield people from the view of others, and on moonless nights. These opportunities for flirting and adultery are a standing village joke, and show the extent of awareness of the high level of neighbour surveillance under which villagers ordinarily live. Thus, Maryam, a married woman from a nearby village, was able to give a detailed account of her neighbour’s attempts to get an abortion.

“In my neighbourhood, at Bologo’s house, there is a girl who is five months pregnant; she’s taking medicines to make herself abort, but it hasn’t dropped yet. She lies on her stomach in the hope that that will force it out.” (Maryam, in her 20s, young married woman, farmer and small trader)

Urban housing conditions afford greater privacy, especially in the new western-style detached homes. In most neighbourhoods, however, multiple families still live in the traditional fashion in the same space, each occupying small, one-or two-room houses built around a central, communal courtyard, where residents spend most of their domestic time, and neighbourly conversation is frequent, giving opportunities similar to those in the villages for spying, overhearing or observing what is happening.

If complications ensue from an abortion and the woman’s health declines to the point of requiring emergency hospital treatment, the secret is revealed both to the family and the neighbours. In Sullé’s account, the woman collapsed and miscarried in public view when fetching water from the pump:

“I remember a sad case three years ago, a woman took modern medicine but nothing happened. It happened later, just as she was going to get water from the pump, the fetus dropped out, there were complications, she was taken to the health clinic and she died.” (Sullé, middle-aged married man, villager, farmer, active in village associations)

Gossip and rumour

Once the abortion secret has been broken, whether by a confidant passing it on or another person observing something, the information tends to permeate further into the social fabric, carried by gossip. Gossip fulfils an important social function in social networks.Citation20 It satisfies curiosity about others, fuels conflict and, above all, prompts compliance with social norms. Gossip is a form of social control, and encourages people to avoid behaviour that might elicit gossip and negative comment. Gossip is more intense in groups with a high relational density, i.e. in communities with many opportunities for meeting and sharing, and among members of long-standing acquaintance.

Rumour, which may be surprisingly powerful, is typically associated with the distortion of information. During my stay in the village, Salimata came seeking my help to get an abortion for her daughter. I offered to take the girl into town to the abortionist on my motorbike, but she declined. This conversation took place in an isolated spot; we were utterly alone and I divulged the episode to no one. About five months later, Maryam from the neighbouring village told me that she had heard in the market that I had helped the hairdresser’s girlfriend get an abortion by taking her to Ouagadougou on a motorbike, with the hairdresser following behind on a bicycle. The fact was that the hairdresser was seeing another girl who lived in Salimata’s courtyard, and that girl also had had an abortion, shortly before Salimata’s daughter. The hairdresser confirmed the other girl’s abortion in an interview with me, but I had had no part in it. The rumour was therefore founded on only partially accurate information, and implicated people who were not directly involved. This reduces the power of the gossip to do harm. This form of social control would be untenable if it were not for the doubt that accompanies rumours.Citation20

In the city, where relationship networks are more fragmented, gossip plays a less important part in everyday life than in the village. The abortion secret is better kept in towns, as access to an abortion provider is easier and involves fewer third parties, and as rumours of abortions spread less widely in the urban area. Thus, people are more open to admitting to having had an abortion to an unknown interviewer in the city; at the same time, each abortion case is not known to the entire entourage, as in the village. Abortion therefore tends to be less of an open secret in the city.

Conclusion

This study found that young women in Burkina Faso, although they want to keep their abortion secret, are impelled to talk to their boyfriends, friends and sometimes female family members about their unplanned pregnancy, first to make the decision to have an abortion and then to find a clandestine abortion provider. The key in keeping the abortion a secret lies in the choice of those with whom the secret is shared; good confidants are those who are bound by secrecy through the bonds of intimacy or through shared transgression. Leaks may still happen, and gossip may then spread the information.Citation20 However, the inaccuracy of gossip can protect the victim of leaks; moreover, the extent of gossip depends on the nature of the social networks involved. Although widely talked about, abortion remains a secret in Burkina Faso, although sometimes a secret known to all.

Sociological theories of secrecy raise questions about the “deviancy” or “taboo” of abortion in Burkina Faso. Abortion is kept a secret by women, not because it is a form of transgression nor from an awareness of having committed a socially condemned act, but more in order to manage their public image in a society where social norms have not caught up with actual behaviour. The intentional withholding of information is instrumental in steering a course through a world of complex and contradictory values and interests. Secrecy can help a society manage rapid social change and the structural contradictions following it.

The abortion narratives reported in this study reveal the wide gap between young people’s desire for sexual activity and unions based on love, and the satisfaction of their wishes. The family network remains the best way of dealing with life’s vagaries: young people find it hard to manage without assistance from their elders. Hence, the prohibition on young people’s sexual activity continues to be highly effective: sexually active young people, especially girls, voice a fear of their parents and of being beaten if they are found to have had pre-marital sex. The fear of attending family planning services to get contraception has similar roots. Thus, it can be argued that young women, their friends and abortion providers in Burkina Faso keep abortion secret because it is a subject on which there is no social consensus, alongside extra-marital sexual activity, contraceptive use by young people and out-of-wedlock pregnancies.

Acknowledgements

This is a translation from a longer version of this paper: L’avortement: un secret connu de tous ? Accès aux services d’avortement et implication du réseau social au Burkina Faso. Sociétés contemporaines 2006;61:41–64, and is reprinted here with kind permission. Part of the article is taken from the author’s PhD dissertation: Measure and meaning of induced abortion in rural Burkina Faso. Demography Department, University of California Berkeley, 2002. The rural data were collected thanks to funds from a Population Council Dissertation Fellowship 2000–2001. The urban data were collected during a study on abortion financed by a Rockfeller Foundation Grant (RF99040#102), coordinated by G. Guiella, Unité d’enseignement et de recherche en démographie, Université de Ouagadougou. Thanks to A Ouédraogo for his invaluable help in collecting both the rural and the urban data. Translation into English by Glenn D Robertson.

References

- United Nations Population Division. Abortion Policies: A Global Review. Vol I. Afghanistan to France. 2001; UN: New York.

- R Lesthaeghe. Reproduction and Social Organization in Sub-Saharan Africa. 1989; University of California Press: Berkeley.

- J Poirier, G Guiella. Fondements socio-economique de la fécondite chez les Mossi du plateau central (Burkina Faso). Les Travaux de l’UERD 1. 1996; UERD: Ouagadougou.

- W Bleek. Avoiding shame: the ethical context of abortion in Ghana. Anthropological Quarterly. 54(4): 1981; 203–209.

- J Johnson-Hanks. The lesser shame: abortion among educated women in southern Cameroon. Social Science and Medicine. 55: 2002; 1337–1349.

- C Rossier. Attitudes towards abortion and contraception in rural and urban Burkina Faso. Demographic Research. 17(2): 2007; 23–58.

- C Rossier, G Guiella, A Ouédraogo. Estimating induced abortion with the confidants’ method. Results from Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso. Social Science and Medicine. 62(1): 2006; 254–266.

- S Henshaw, S Singh, B Oye-Adeniran. The incidence of induced abortion in Nigeria. International Family Planning Perspectives. 24(4): 1998; 156–164.

- A Desgrées du Loû, P Msellati, I Viho. Le recours à l’avortement provoqué a Abidjan: Une cause de la baisse de la fécondité ?. Population. 54(3): 1999; 427–446.

- A Guillaume. The role of abortion in the fertility transition in Abidjan (Côte d’Ivoire) during the 1990s. Population. 58(6): 2003; 657–685.

- Beguy D, Ametepe F. Utilisation de la contraception moderne et recours à l’avortement provoqué: deux mécanismes concurrents de régulation des naissances ? Chaire Quételet Santé de la Reproduction au Nord et au Sud: de la Connaissance à l’Action, Louvain-la-Neuve, Belgium, 17–20 November 2004.

- G Simmel. The secret and the secret society. KW Wolff. The Sociology of Georg Simmel. 1950; Free Press: New York.

- S Tefft. Secrecy: A Cross-Cultural Perspective. 1980; Human Sciences Press: New York.

- M Couetoux. Figures du Secret. 1981; Presses Universitaires de Grenoble: Grenoble.

- C Bledsoe, G Pison. Nuptiality in Sub-Saharan Africa: Contemporary Anthropological and Demographic Perspectives. 1994; Clarendon Press: Oxford.

- T Locoh. Fertility decline and family changes in sub-Saharan Africa. Journal of African Population Studies. 7(2–3): 2002; 17–47.

- NL Howell. The Search for an Abortionist. 1969; University of Chicago Press: Chicago.

- JS Victor. Privacy, intimacy and shame in a French community. S Tefft. Secrecy: A Cross-Cultural Perspective. 1980; Human Sciences Press: New York, 100–118.

- G Simmel. Friendship, love and secrecy. American Journal of Sociology. 11: 1906; 457–464.

- T Gregor. Exposure and seclusion: a study of institutionalized isolation among the Mehinaku Indians of Brazil. S Tefft. Secrecy: A Cross-Cultural Perspective. 1980; Human Sciences Press: New York, 81–99.