Abstract

This paper comments on the provision of birthing services in Sichuan and Shanxi Provinces in China within a policy context. The goal was to understand possible unintended and harmful health outcomes for women in the light of international evidence, to better inform practice and policy development. Data were collected from October 2005 to April 2007 in 25 hospitals across 13 counties and one city. Normal and caesarean birth records were audited, observations made of facilities and interviews conducted with officials, administrators, health workers, women who delivered in hospital facilities and women who delivered at home. We argue that in the context of a neo-liberal health economy with poorly developed government regulatory policies, those with the power to pay for maternity care may be vulnerable to a new range of risks to their health from those positioned to make a profit. While poor communities may lack access to basic services, wealthier socio-economic groups may risk an increase in maternal morbidity and mortality through the overuse of avoidable intervention. We recommend a stronger evidence base for hospital maternity services and changes to the role of the State in countering systemic problems.

Résumé

Cet article examine les services de maternité des provinces chinoises du Sichuan et du Shanxi dans un contexte politique. Il s’agissait de cerner d’éventuels effets indésirables pour les femmes à la lumière des données internationales, afin de mieux informer la pratique et la définition des politiques. Les données ont été recueillies d’octobre 2005 à avril 2007 dans 25 hôpitaux de 13 comtés et une ville. Les dossiers des accouchements normaux et par césarienne ont été contrôlés, les équipements et les fonctionnaires ont été observés, des entretiens ont été organisés avec des administrateurs, des agents de santé, des femmes qui avaient accouché à l’hôpital ou à la maison. Dans le contexte d’une économie de santé néolibérale avec des politiques régulatrices gouvernementales mal définies, il apparaît que les individus ayant les moyens de payer des soins de maternité peuvent être vulnérables à un nouvel éventail de risques sanitaires créés par ceux qui souhaitent faire des bénéfices. Alors que les communautés pauvres n’ont parfois pas accès aux services essentiels, les groupes socio-économiques plus aisés risquent de subir une hausse de la morbidité et de la mortalité maternelles en raison du recours excessif à des interventions superflues. Nous recommandons d’appuyer les services hospitaliers de maternité sur une base factuelle plus solide et préconisons de changer le rôle de l’État pour corriger les problèmes systémiques.

Resumen

Este artículo trata de la prestación de servicios de parto en las provincias de Sichuan y Shanxi, en China, en un contexto de políticas. El objetivo era entender posibles resultados de salud imprevistos y peligrosos para las mujeres en vista de la evidencia internacional, con el fin de informar mejor las prácticas y la formulación de políticas. Se recolectaron datos desde octubre de 2005 hasta abril de 2007, en 25 hospitales de 13 condados y una ciudad. Se realizaron auditorías de los registros de partos normales y por cesárea, se observaron los establecimientos de salud y se realizaron entrevistas con funcionarios, administradores, trabajadores de la salud, mujeres que dieron a luz en instalaciones hospitalarias y mujeres que dieron a luz en su hogar. Argumentamos que, en el contexto de una economía de salud neo-liberal con políticas reguladoras gubernamentales mal formuladas, aquéllas con el poder para pagar por atención de maternidad posiblemente sean vulnerables a una nueva gama de riesgos a su salud de aquéllos posicionados para hacer ganancias. Aunque las comunidades pobres carecen de acceso a los servicios fundamentales, es posible que los grupos socioeconómicos más adinerados afronten una tasa más elevada de morbimortalidad materna debido al uso excesivo de intervención evitable. Recomendamos una base de evidencia más sólida para los servicios obstétricos hospitalarios, así como cambios a la función del Estado en contrarrestar los problemas sistémicos.

Economic prosperity and the ability to purchase better health care are generally considered protective of staying well. In analyses of health and health care in resource-limited countries it is the rural poor for whom death and risk are generally greater. Maternal mortality ratios in China are illustrative; women in wealthier coastal regions of China do survive birth better than women in rural and remote regions.Citation1Citation2 In 2004 in Shanghai, the maternal mortality ratio was 9.6 per 100,000 births, but it was 161 per 100,000 births in western and rural Xinjiang and 310.4 per 100,000 in Tibet.Citation2–4

China is classified as a lower middle income country with wide geographical and cultural variation. It struggles to provide high quality health care for minority and other populations that live in remote and rural locations. Yet China’s efforts to improve safety during delivery, including greater access to hospitals and emergency obstetric care, have contributed to an impressive 30-fold reduction in maternal mortality ratios over 55 years since 1950 from 1,500 per 100,000 births in 1950 to 47.7 per 100,000 births in 2005.Citation5Citation6 However, as happened in most Western countries, this occurred concurrently with an increased level of medicalisation and technical intervention in normal births,Citation7 which in some parts of China exceed that of most other nations.Citation2

This paper comments on the provision and quality of birthing services in Sichuan and Shanxi Provinces in southwest and central China, respectively, drawing on data collected from October 2005 to April 2007, in light of key government policies and approaches to financing health care since 1978. The goal was to understand possible unintended and harmful health outcomes for women in the light of international evidence, to better inform practice and policy development.

Health systems reforms in China

The substantial changes to China’s health care system as a result of rapid economic liberalisation instigated under Deng Xiaoping’s Reform and Opening Policy of 1978 have received extensive comment from Chinese and international analysts.Citation8Citation9 The effects across China have been uneven. Because of cost and loss of personnel to better paid, larger centres, health facilities in poor localities are more limited than before the 1978 reforms, while access to highly sophisticated care is increasing in wealthier areas as incomes rise and services expand.Citation10Citation11

As Blumenthal and Hsiao point out, China has “adopted [wittingly or not] the strategies of some U.S. proponents of radical health care privatisation”.Citation12 State expenditure on health care as a proportion of total health expenditure has decreased, while private expenditure has increased, particularly out-of-pocket payments borne by individual service users. In 2002, as a share of total expenditure, the Chinese central Government paid for only 15% of the nation’s health care, compared to 32% in 1978. The share paid by medical insurance plans also dropped, from 47% in 1980 to 27% in 2002. Out-of-pocket payments by individuals have steadily risen to 67% in 2002.Citation13 Hospitals have been driven to overuse new technology and drugs, and provide unnecessary services, to generate much-needed revenue.Citation14 Efforts since 2003 to revive health insurance programmes through China’s new cooperative medical scheme have had variable success and are at different stages of roll-out across the nation.Citation15

International experience has shown that no health care system can be managed solely on free-market principles,Citation16 yet health care in China is overridingly market driven. In addition to increasing marketing of services, more private investment and mixed ownership structures of health facilities within the public sector, the proportion of private providers continues to grow outside, but also in association with, the public sector.Citation17Citation18 This fuels competition between all providers, making regulation of an increasingly complex mix of both private (legal and illegal) and public services by government even more difficult.

While debate continues among policymakers, an over-reliance on the ability of the market to deliver, or at least not undermine, social equity appears to persist in China. The Eleventh Five Year Plan endorses “opening up” the economy to investment, including foreign capital, without recognition of the need for greater regulation of the market in regard to “public goods” such as health care.Citation19

Evidence indicates that countries with a high proportion of births in institutions assisted by skilled attendants have low maternal mortality ratios.Citation20 Thus, China decided a decade ago to make efforts within the health system to make delivery safer. In 1998, as a companion project within the framework of a national rural health reform demonstration project entitled: “Reform of the Basic Health Services in China”, in seven provinces, a Reproductive Health Improvement Project was initiated, to incorporate basic reproductive health services into a revitalised primary health care system in poor areas. Promotion and provision of safe delivery services was identified as one of the key priorities.Citation21 A project to decrease maternal mortality ratios and eliminate newborn tetanus was then begun in 2000, commonly referred to as the “Decreasing Project”,Citation22 which initially targeted 12 western rural provinces. The goal of raising the hospital delivery rate was contained in the 2002 Decision by the Central Committee of the Chinese Government.Citation23 The Government has since imposed ambitious targets for raising hospitalised birth rates on resource-strapped health facilities, alongside improvement of quality of care. The “Decreasing Project” was expanded to central China in 2005, including both Sichuan and Shanxi Provinces.Citation24 Ensuring that every pregnant woman delivers her baby in hospital instead of at home continues to be supported through projects such as “Action 120”, launched in September 2006 by the China Foundation for Poverty Alleviation.Citation25 Even so, the number of births in hospitals still varies greatly across China today, with stark rural and urban differences. In Shanghai, virtually all women give birth in a hospital,Citation26 while in some rural areas up to 72.5% of women gave birth at home in 2004.Citation27

Methods

Our aim was to investigate the relationship between government policy, the quality of birthing services and maternal health outcomes. Key indicators of health service quality were examined – rates of intervention, specifically rates of caesarean section, ultrasound use and pain relief, place of birth and type of attendant. Data were collected from October 2005 to April 2007 across nine counties in Shanxi Province and three counties and one city in Sichuan Province. The data from Shanxi Province were collected by Yu Gao as part of her doctorate research and the data from Sichuan Province were collected by all team members. Hospitals were purposively sampled because of their location in areas of high, medium and low maternal mortality ratios, as a crude indication of health service performance. These ratios have not been included in this paper as data presented are not analysed in relation to them. Sites were also selected on the basis of increasing remoteness and distance from provincial capitals to encompass a diversity of facilities in terms of types of services, education and training of staff, financing and populations served. In Sichuan the three counties were located close to the capital in the north, in the southeast and in a remote mountainous region in the south with an ethnic minority population. The nine counties in Shanxi were located in the southeast, north and central areas of the province. Included in our sample are one major provincial level hospital, 11 county hospitals and 13 township hospitals.

We sampled between 9% and 25% of accessible birth records. In facilities where the numbers were small (50 records or less) we sampled 100% of cases. A total of 1,345 normal (n=889) and caesarean (n=456) birth records were audited. In both provinces we conducted observations of facilities and structured and semi-structured interviews with officials from the county and provincial level Bureau of Health in each county (n=5), administrators, obstetricians, nurses and midwives in the hospitals (n=75) women who used hospital facilities (n=96) and women who gave birth at home (n=91). Research instruments for record audits, observations and most of the interviews were based on the World Health Organization (WHO) Safe Motherhood Assessment Tools.Citation28 These were modified by refining, adding and removing questions and translated into Mandarin to maximise appropriateness and effectiveness within the social, cultural and political context of our research sites.

Ethics approvals for this research were granted by the Charles Darwin University Human Research Ethics Committee in 2005 (approval no. HO5071) and 2006 (approval no. HO5102) and our partner hospitals in each province in China.

Results

Intervention: caesarean sections, pain relief and ultrasound use

Not all hospitals had the equipment and expertise to perform caesarean sections. All county-level hospitals in our sample performed caesareans in both provinces. In Sichuan two township hospitals were able to perform caesareans. The third, more isolated township hospital in southern Sichuan and all ten township hospitals sampled in Shanxi had neither the equipment nor staff with the necessary skills. For many women accessing emergency obstetric care meant several hours travel by road, sometimes in addition to travel on foot. Records for caesarean births were available for audit in 12 hospitals. Caesarean rates ranged from 6.8% to 66.7%. Five hospitals, three in Shanxi and two in Sichuan, had rates above 40%. Three of these, one in Shanxi and two in Sichuan, had rates above 60%. The average rate was 34.5%.

In only three facilities we sampled were caesarean rates within the range of 5% to 15% recommended by the WHO.Citation29 These were 6.8%, 10.1% and 14.8% and were found in more isolated rural facilities of Shanxi. These facilities also have low episiotomy rates (2.1%, 9.6% and 10.9%, respectively) and no pubic shaving, and women were accompanied by family members while they were giving birth.

Caesarean births were analysed for frequency and while attempts were made to determine whether they were performed for medical reasons or at maternal request, this data was problematic. There was an association between higher rates of maternal request caesareans and larger urban hospitals in both provinces. The two highest rates observed, 47% and 48.4%, were in large county hospitals close to the provincial capitals. Smaller rural hospitals tended to have lower rates of caesarean section.

None of the women in audited births received any pain relief during normal birth yet many, when interviewed, expressed great fear in relation to the pain of childbirth, especially after having had a child. All women were delivered in lithotomy position, at times subjected to routine episiotomy (rates in two Sichuan hospitals were 58% and 92.5%) and in most cases delivered alone without the option of family support from the hospital.

We observed ultrasound scans frequently being used in Chinese hospitals by qualified staff and also in private, unregulated clinics, with charges levied for each scan. In some cases ultrasound scans were performed to the exclusion of other essential components of care such as blood pressure and urine tests. We recorded instances of women having up to five ultrasounds in our most remote site in Sichuan in normal pregnancies. According to many women we interviewed, other aspects of antenatal care were considered less important than ultrasound and even unnecessary if the fetus was observed to be in the correct position. In one county hospital we studied, not only was ultrasound used antenatally, but also post-natally within the first few days after birth. The reason given by staff was to check if the placenta and membranes were gone, yet there is no evidence to support such a practice.Citation30 The director, however, explained that post-natal scans were performed to fund capital works, salaries and services, and also the pensions of retired staff.

Costs of birth

There is a large range of fees levied for giving birth in hospital. Interviews we conducted with leaders of county hospitals suggest these fees are often determined by the capacity of the patients to pay, rather than the actual costs of service. Normal birth without interventions is relatively low cost and therefore not attractive as a source of revenue. Charges for vaginal delivery levied in county or township hospitals ranged from 200–1,000 yuan and could cost 2,000 or more at provincial level. (Annual household income in rural areas in our study ranged from 2,200-3,500 yuan.) A caesarean section cost up to 8,000–10,000 yuan in a major maternal health care hospital in one provincial capital and from 1,000–2,000 in county hospitals. Recent government initiatives such as the new cooperative medical (insurance) schemeCitation15 in Shanxi were associated with increases in the rate of hospital birth in our samples.

Costs are not restricted only to hospital fees. There are associated costs for travel, accommodation outside hospital and food, for the mother and accompanying family members. While costs for a normal hospital birth in our site in south Sichuan should not, according to officials and hospital staff, exceed 50 yuan if the mother is insured, in practice costs reported by women ranged from 400–3,000 yuan. Most of these costs were for medicines, only a few of which were covered by insurance, and for travel and accommodation. Women interviewed did not know what the medicines they received were or why they were administered. Due to decisions made at county level, women were also required to remain in this hospital for a minimum of two days in order to qualify for any insurance coverage.

Discussions and observations in hospitals in Shanxi show how in some places the requirement to offer a “red bag” – an informal form of payment or gift made by the patient to the physician managing the birth – is creating further financial difficulty for patients and challenges for hospital administrators who are trying to manage this rapidly changing situation.

Medical expenditure in general has become an important source of transient poverty in rural China.Citation31 In parts of Sichuan Province we found reimbursements for costs associated with birth ranged from only 20% to 30% of total cost which meant that costs for normal birth were still high for many women, often comprising more than one third of the household average annual income. Despite government subsidies aimed at reducing the out-of-pocket costs of hospital birth our research confirms that this still remains unaffordable for many women in rural townships and villages in both provinces.

Attendants at birth

Efforts to encourage hospital birth throughout China are intended to ensure women’s access to trained birth attendants and emergency obstetric services. Despite official claims that untrained midwives no longer practise in China,Citation32 our research confirms that in remote areas midwives whose training has been predominantly or entirely informal, known as jie sheng po, do still practise with the reluctant consent and surveillance of higher level medical facilities.Citation33 Birth at home in the company of female relatives or jie sheng po remains common, particularly for geographically isolated ethnic minorities, despite considerable efforts to change this. In our most isolated research site in Sichuan, only 6 (17%) out of 35 women interviewed, who gave birth in the last ten years, did so in the presence of a trained birth attendant. Interview data suggest this is related to cost, transport, perceptions of the quality of hospital birthing services and staff and socio-political and cultural factors.

On the other hand, we observed a predominance of doctors compared to trained midwives in all hospitals in our study. In one township hospital the 14 medical staff were all doctors. Although midwives retain authority over normal birth in some settings, this is becoming a less common proportion of total births in China.Citation34 Almost all the doctors we worked with at county and township level had only completed three-year medical programmes in colleges, although some had one year additional technical training under highly skilled obstetricians in big cities. While higher level doctors are university educated, formally trained midwives are taught in colleges. In one instance, for example, we discovered when interviewing the senior obstetrician at a rural county maternal and child health hospital that her formal training in the early 1980s was in midwifery. She was taught to perform caesarean sections by a hospital colleague two years after beginning work as a midwife. She has had no further formal or informal training in surgery or obstetrics.

The availability of well-trained birth attendants is hampered further by “red bag” practices whereby students and junior doctors are at times precluded from gaining practical experience by senior physicians, who are pocketing the additional “red bag” money.

Place of birth

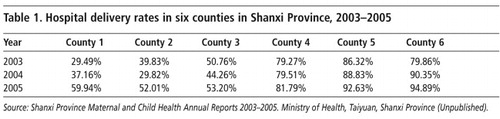

Our own fieldwork confirms over 80% of births occur outside hospital in some remote ethnic minority populations and frequently in circumstances where women have no access to obstetric emergency services. Data from our most isolated research site in Sichuan suggest that a shift away from home birth to giving birth in hospitals is underway, albeit very recent, and only among a small minority of women. The six women discussed above who gave birth in hospital did so within the last three years. Table 1 shows trends in increasing rates of hospital birth across six counties in Shanxi from 2003 to 2005. Rates of increase were greater in counties where the Decreasing Project was underway.

We also found an association between insurance status and place of birth, whereby uninsured women or recently insured women were less likely to deliver in hospitals. While in parts of Shanxi we found a positive association between insurance coverage and hospital birth, through the Decreasing Project and cooperative medical scheme, we also found instances where the insurance scheme was inadequate for encouraging women to give birth in hospitals, as the costs remained high.

Interpretation and implementation of China’s fertility policy, commonly referred to as the “one-child policy”, varies widely across China in terms of the number of children permitted, spacing of children and consequences for women who have additional children.Citation35 It has been suggested that this policy has led to under-reporting of subsequent births and pregnancies, with women avoiding surveillance by delivering outside the hospital system.Citation36Citation37 We found three instances of this in our most isolated Sichuan site.

Discussion

Increasingly across China, medical practices, the “one-child policy”, fear of pain in normal birth, mortality and morbidity and cultural practices around childbirth such as giving birth at auspicious times, changes in the birth attendant toward a predominance of obstetricians, the place of birth and even “red bag” practices appear to combine with policies on health care financing to produce rates of intervention, or the likelihood of such rates, that are well above accepted international recommendations.

The shift to hospital birth in post-reform China has aimed to improve outcomes for women who had no access to trained attendants or emergency obstetric care, particularly in the rural areas. Inarguably, this has resulted in a dramatic fall in maternal mortality ratios. Paradoxically, however, in some parts of China, including most of the hospitals in our sample, this may have also increased risk of morbidity and even death to mothers and infants through injudicious or over-use of interventionist techniques. Once birth is located in hospitals, particularly those that are larger and more technologically sophisticated, the symbols and costs that are attached to birth can become those also attached to treatment for illness, which confirm the importance and status of technology and specialised medicine. In China, some women choose caesarean section to avoid birthing on inauspicious dates, the pain of contractions or perceived maternal or fetal risk that may decrease their chances of a “quality” child under the one-child policy.Citation38–40 The great majority of women giving birth, however, are actually low risk and do not require the technology available in larger hospitals unless problems arise.Citation41 As a consequence, pregnancy and normal vaginal delivery are being redefined, in China, as elsewhere, as a risk to be managed through increased, routine intervention.

The efficacy, implications and cost-effectiveness of such interventions are currently being debated internationally. Some have been proven to be ineffective and unsafe,Citation42Citation43 for example, the widespread use of ultrasound in normal pregnancy has been the subject of particular scrutiny and various studies have concluded that routine screening ultrasonography has not improved perinatal outcomes.Citation44

When used in an emergency, caesarean section can save the lives of mother and infant. Access is considered an indicator of service quality, particularly in poor areas where it may be unavailable. However, when performed without medical indications it risks avoidable morbidity or even death. Operative birth has been shown to be associated with increased maternal mortality, post-operative complications and neonatal respiratory distress.Citation42Citation43 Similarly, the first results of the 2005 WHO Global Survey of Maternal and Perinatal Morbidity and Mortality indicate that high rates of caesarean section are associated with harm and poor health outcomes for mother and infant.Citation45 Yet rates continue to increase in China and worldwide, not in association with emergencies, but with an increasing trend for women to choose or have an elective caesarean recommended to them rather than normal birth.Citation45Citation46 We observed a direct correlation between larger, more urban hospitals and higher rates of caesarean sections with a greater proportion of caesarean births being attributed to requests from women. However, while requiring further investigation, our data suggest that the proportions of caesareans attributed to requests from women may be overstated.

Hopkins interrogated the reasons Brazilian women are “choosing” caesarean.Citation47 Her analysis throws into question assumptions that women are able to make well-informed and independent decisions, considering, for instance, the power differences between women and their doctors. Yang has noted that although Chinese physicians are less powerful in the profession–state relationship than their counterparts in many countries, they are powerful in the doctor–patient relationship. Obstetricians in mainland China do not have an independent professional organisation and the Chinese Medical Doctor Association, formed in 2002, is said to be closer to a government agency than a professional organisation.Citation48 Questions similar to those posed by Hopkins need to be asked in relation to the Chinese context and the rising rates of women portrayed as choosing to undergo caesarean section births.

From an analysis of nationwide health surveys published in 2006, Tang, Li and Wu report a dramatic rise in caesarean deliveries in China’s cities since 1990, rising from 18.2% in 1990–1992 to 39.5% in 1998–2002.Citation7 We have similarly observed many rural Chinese services pursuing, although more slowly, a reliance on revenue-raising technology and overuse of drugs similar to that of wealthier areas.Citation49 Yet in both rural and urban areas, the increasing use of technology is driven by economic forces, often unrelated to evidence of best clinical practice. Hospitals promote costly, revenue-raising, interventionist-style birth as health care providers operate under the influence of market forces and put income-generating activities ahead of health concerns.Citation50 As a result, women are subjected to unnecessary technological interventions and risk becoming an exploitable source of income. Ironically the hospitals that have remained relatively isolated and service a generally poorer population have practices that are closer to current international, evidence-based practices for normal birth. Yet these hospitals also still have poorer capacity to manage emergency obstetric care. In the process of providing higher quality care to women, the risk is that, given current trends in China, these rural services will likely follow similar trends to wealthier urban facilities, leading to unintended and harmful outcomes for women and infants.

Several studies have found that Chinese women with urban social health insurance or government health insurance were more likely to have caesarean births than those who were uninsured.Citation26Citation51 Bogg and colleagues showed in their work that the fee-for-service system in China meant that the majority of uninsured women delivered out of hospital, while more than 90% of those covered by health insurance delivered in a township or county hospital. Less than half of the non-insured women had their deliveries supervised by a doctor or midwife, while more than 90% of those covered by the cooperative medical system and 85% of those covered by another form of health insurance had access to qualified supervision of delivery.Citation52 We found a similar association in our research where, as noted above, implementation of health insurance schemes varies greatly across China. Where these schemes become effective in supporting hospital birth, our concern is that a positive relationship between health insurance status and intervention rates will strengthen.

In China, as elsewhere, changes to the birth attendant role can exacerbate an interventionist approach to birth. The contemporary reliance on and trust in what Giddens (1990) calls “expert systems”, that include institutions such as hospitals and the medical experts they employ, is relatively recent.Citation53 It has been accompanied by a growth in tertiary training and professional gate-keeping worldwide.

Whereas Mao launched a sustained attack on the status and privileges of the medical profession, under Deng the medical profession and biomedical knowledge rose significantly.Citation54 The subsequent ideological power conferred on doctors has given them authority over other professional groups in the health care system (J Yang, Personal communication, 10 July 2006). The status and power of the obstetrician compared to the midwife in China now appears well entrenched in the workplace.Citation34

Conclusion

The provision of birthing services in China is challenging in ways similar to other nations but also in ways that are unique to China. We concur with Smith, Wong & Zhao (2004) who argue that the current dominant model, derived from the United States, where there are unusually high levels of private health expenditure, low levels of public health funding and few midwives working in normal, low-cost birth, is not one for China to emulate.Citation55 While China has achieved remarkable results in improving maternal health services, if we look to the future, the country may well be in need of alternative models for the provision of birthing services. There appears to be little acknowledgement that the overall shift toward interventionist, hospital-based births may not be economically sustainable, nor any concern that such a birth system may cause avoidable morbidity and mortality.

We are not suggesting that birth services in China would be more appropriately provided to rural Chinese women outside hospitals. Given the limitations in resources and the remoteness that would prevent access to emergency services when needed, this is hardly feasible. However, measures need to be taken to prevent the rise of intervention rates, in particular caesarean section births, in smaller, rural hospitals that are currently evident in the larger technologically sophisticated hospitals of China. The nature of the place of birth, rather than the place of birth per se, needs to change, and the balance between obstetricians and midwives needs to be considered in light of the increasing duration and cost of medical education.

The introduction of evidence-based practice could also be used to address the inadvertent health consequences of policy that has created systemic problems for both poor rural communities and wealthier urban populations. Particularly important in this regard is the application of criteria or disincentives for the use ultrasound and caesarean section. At the level of the State, health services need to function efficiently and effectively within an appropriate financing model and strong policy environments. There appears to be a window of opportunity associated with the new national emphasis on improving rural well-being, including through improvements to the rural health care system.Citation19 It may be possible to prevent some rural regions from pursuing the same trajectory as in urban China, that is putting women at unnecessary risk through overuse of intervention. At the same time the economic exploitation of wealthier women during birth should be stopped.

In China many analysts and policy-makers now realise that a large part of the public health system, as well as other public services, must be the responsibility of the government.Citation50 One of the strongest proponents of a market-based system, the World Bank, has recently called for China to strike a balance between a planned system of health care and the free market.Citation16 Increased central Chinese government input and funding into “education, health, science, and other social/development needs, as a share of overall spending and relative to GDP” has been called for by the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development.Citation56 The country’s extraordinary economic growth would appear to position China well, at least financially, to effect positive changes in its health care system.Citation12

The challenge facing us globally, not just in China, is how to develop and implement improved maternity care in complex political, social and economic contexts. Modern birth, that privileges over-medicalised hospital care against evidence of best practice, runs counter to the best interests of women.

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our thanks to the many government representatives, hospital administrators and leaders at provincial, county and township level who gave their time and support so generously in China. We also wish to thank David Goodman, Jingqing Yang and Beatriz Carrillo for very useful comments on an earlier draft of this paper. This research was funded by the Australian Research Council, the West China Second University Hospital, Sichuan Province and the Second Hospital of Shanxi Medical University, Shanxi Province.

References

- JS Akin, WH Dow, PM Lance. Changes in access to health care in China, 1989–1997. Health Policy and Planning. 20(2): 2005; 80–89.

- Department of International Organisations Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China. China’s Progress towards the Millenium Development Goals. 2005; United Nations System in China: Beijing.

- Z Chen. [The present condition and future of Chinese public health]. Management Review. 16(2): 2004; 3–6.(In Chinese)

- China Population Web. [Tibet: Free hospital birth achieved in the main]. China Population Web, 2005. At: <chinapop.gov.cn/rkxx/gdkx/t20050912_26326.htm>. Accessed 2 July 2007. (In Chinese)

- T Hesketh, WX Zhu. Health in China: maternal and child health in China. British Medical Journal. 314: 1997; 1898.

- National Maternal and Child Health Surveillance Office. [National Maternal and Child Health Surveillance and Annual Report]. Issue 4. 2006; National Maternal and Child Health Surveillance Office: Chengdu(In Chinese)

- S Tang, X Li, Z Wu. Rising cesarean delivery rate in primiparous women in urban China: from three nationwide household health surveys. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 195(6): 2006; 1527–1532.

- J Banister, X Zhang. China, economic development and mortality decline. World Development. 33: 2005; 1.

- WC Hsiao. Disparity in health: the underbelly of China’s economic development. Harvard China Review. 5: 2004; 64–70.

- G Bloom, X Gu. Health sector reform: lessons from China. Social Science and Medicine. 45(3): 1997; 351–360.

- Henderson G. Myths and reality: the context of emerging pathogens in China. Paper presented to Roundtable of the Congressional-Executive Commission on China, 2003. 12 May 2003.

- D Blumenthal, W Hsiao. Privatization and its discontents - the evolving Chinese health care system. New England Journal of Medicine. 353(11): 2005; 1165–1170.

- United Nations Health Partner Group in China. A Health Situation Assessment of the People’s Republic of China. July. 2005; UNHPG: Beijing.

- Ministry of Health National Development and Reform Commission and Ministry of Finance. Health and Macroeconomics in China. 2003; Government of China: Beijing.

- Wagstaff A, Lindelow M, Gao J, et al. Extending Health Insurance to the Rural Population: An Impact Evaluation of China’s New Cooperative Medical Scheme. In: Impact Evaluation Series. Washington DC, 2007.

- World Bank. Health Service Delivery in China: A Review. Briefing Note No.4. February. 2005; World Bank: Washington DC.

- Y Hua. China debates medical reform, privatization. Asia Times. 2004 At: <www.atimes.com/atimes/printN.html>. Accessed 26 June 2006

- R Lipson. Investing in China’s hospitals: China is considering ways to revamp its healthcare system. China Business Review. 2004; 10–14.

- Central Committee, Chinese Communist Party. The Eleventh Five Year Plan. At: <english.ningo.gocv.cn/col/col450/index.html>. Accessed 8 December 2006

- V Fauveau. Strategies for reducing maternal mortality. Lancet. 368: 2006; 2121–2122.

- J Kaufman, J Fang. Privatisation of health services and the reproductive health of rural Chinese women. Reproductive Health Matters. 10(20): 2002; 108–116.

- Y Peng. [Implementing the project of reducing maternal mortality and eliminating newborn tetanus.]. Maternal and Child Health Care of China. 2000; 68–72.(In Chinese)

- Central Committee, Chinese Communist Party, and State Council on Further Strengthening Rural Health. “The Decision”. 19 October. 2002

- ZY Guo. “Decreasing Project” Management. 2005; Ministry of Health: Taiyuan(In Chinese)

- Women of China. Action 120: Maternal and Infant Project. 2006; Women of China: Beijing.

- Q Xu, H Smith, Z Li. Evidence-based obstetrics in four hospitals in China: an observational study to explore clinical practice, women’s preferences and provider’s views. BMC Pregnancy and Birth 2001. At: <www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2393/1/1>. Accessed 3 July 2006

- O Anson. Utilization of maternal care in rural HeBei Province, the People’s Republic of China: individual and structural characteristics. Health Policy. 70: 2004; 197–206.

- World Health Organization. Safe Motherhood Needs Assessment. WHO/RHT/MSM/(96.18 Rev 1). 2004; Department of Reproductive Health and Research: Geneva.

- United Nations Population Fund. The Promise of Equality: Gender Equity, Reproductive Health and the Millennium Development Goals. 2005; UNFPA: New York.

- M Enkin, MJNC Keirse, I Chalmers. A Guide to Effective Care in Pregnancy and Childbirth. 1989; Oxford University Press: Oxford.

- Y Liu, K Rao, WC Hsiao. Medical expenditure and rural impoverishment in China. Journal for Health Population and Nutrition. 21(3): 2003; 216–222.

- Midwifery phased out in China’s rural areas. People’s Daily. 30 September. 2002 At: <china.org.cn/english/Life/44748.htm>. Accessed 18 January 2007

- J Vials. Midwifery and health care in China. British Journal of Midwifery. 7(7): 1999; 451–455.

- A Harris, S Belton, L Barclay. Midwives in China: “Jie sheng po” to “zhu chan shi”. Midwifery. 2007(In press)

- B Gu, F Wang, Z Guo. China’s local and national fertility policies at the end of the twentieth century. Population and Development Review. 33(1): 2007; 129–147.

- T Hesketh, L Lu, ZW Xing. The effect of China’s one-child family policy after 25 years. New England Journal of Medicine. 353(11): 2005; 1171–1176.

- H Ni, AM Rossignol. Maternal deaths among women with pregnancies outside of family planning in Sichuan, China. Epidemiology. 5(5): 1994; 490–494.

- Greenhalgh S. Planned births, unplanned persons: contradictions in China’s socalist modernisation project. Seminar on Social Categories in Population Health. Cairo, 1999.

- LY Lee, E Holroyd, CY Ng. Exploring factors influencing Chinese women’s decision to have elective caesarean surgery. Midwifery. 17(4): 2001; 314–322.

- H Lei, SW Wen, M Walker. Determinants of caesarean delivery among women hospitalized for childbirth in a remote population in China. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology Canada. 25(11): 2003; 937–943.

- K Johnson, B-A Daviss. Outcomes of planned homebirths with certified professional midwives: large prospective study in North America. BMJ. 330: 2005; 1416–1422.

- S Bewley, J Cockburn. Commentary I. The unethics of “request” caesarean section. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 109: 2002; 593–596.

- S Bewley, J Cockburn. Commentary II. The unfacts of “request” caesarean section. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 109: 2002; 597–605.

- T Roberts, J Henderson, M Mugford. Antenatal ultrasound screening for fetal abnormalities: a systematic review of studies of cost and cost effectiveness. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 109(1): 2002; 44–56.

- J Villar, E Valladares, D Wojdyla. Caesarean delivery rates and pregnancy outcomes: the 2005 WHO global survey on maternal and perinatal health in Latin America. Lancet. 367(3 June): 2006; 1819–1829.

- J Morrison, JM Rennie, PJ Milton. Neonatal respiratory morbidity and mode of delivery at term: influence of timing of elective caesarean section. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 102: 1995; 101–106.

- K Hopkins. Are Brazilian women really choosing to deliver by cesarean?. Social Science and Medicine. 51: 2000; 725–740.

- J Yang. The privatisation of professional knowledge in the public health care sector in China. Health Sociology Review. 15: 2006; 16–28.

- T Hesketh, WX Zhu. Health in China: the healthcare market. British Medical Journal. 314: 1997; 1616–1622.

- United Nations Country Team in China. A Current Perspective: Updated Common Country Assessment. 2003; United Nations Agencies: Beijing.

- WW Cai, JS Marks, CHC Chen. Increased cesarean section rates and emerging patterns of health insurance in Shanghai, China. American Journal of Public Health. 88(5): 1998; 777–780.

- L Bogg, K Wang, V Diwan. Chinese maternal health in adjustment: claims for life. Reproductive Health Matters. 10(20): 2002; 95–107.

- A Giddens. The Consequences of Modernity. 1990; Polity Press: Cambridge.

- Deng X. Respect Knowledge, Respect Trained Personnel. In: China Central Committee of the Communist Party of China, editor. Selected Works of Deng Xiaoping. Beijing: Foreign Languages Press, 1977. p.53–54.

- P Smith, C Wong, Y Zhao. Public Expenditure and Resource Allocation in the Health Sector in China. Paper prepared for World Bank. 2004

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. Challenges for China’s Public Spending: Toward Greater Effectiveness and Equity. 2006; OECD: Paris.