Abstract

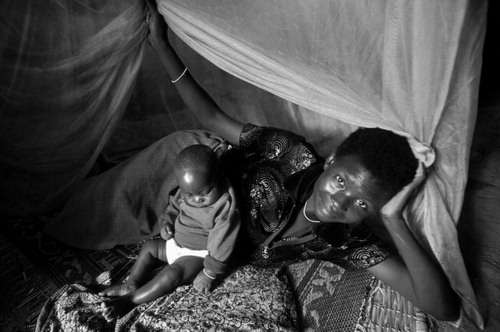

In resource-poor countries, the high cost of user fees for deliveries limits access to skilled attendance, and contributes to maternal and neonatal mortality and the impoverishment of vulnerable households. A growing number of countries are experimenting with different approaches to tackling financial barriers to maternal health care. This paper describes an innovative scheme introduced in Ghana in 2003 to exempt all pregnant women from payments for delivery, in which public, mission and private providers could claim back lost user fee revenues, according to an agreed tariff. The paper presents part of the findings of an evaluation of the policy based on interviews with 65 key informants in the health system at national, regional, district and facility level, including policymakers, managers and providers. The exemption mechanism was well accepted and appropriate, but there were important problems with disbursing and sustaining the funding, and with budgeting and management. Staff workloads increased as more women attended, and levels of compensation for services and staff were important to the scheme’s acceptance. At the end of 2005, a national health insurance scheme, intended to include full maternal health care cover, was starting up in Ghana, and it was not yet clear how the exemptions scheme would fit into it.

Résumé

Dans les pays pauvres, le montant élevé des contributions demandées aux patientes pour les accouchements limite l’accès à des soins de qualité, tout en contribuant à la mortalité maternelle et néonatale et à l’appauvrissement des ménages vulnérables. Un nombre croissant de pays expérimentent différentes méthodes pour lever les obstacles financiers aux soins de santé maternelle. Un projet novateur, introduit au Ghana en 2003, exonérait toutes les femmes enceintes du paiement des accouchements et prévoyait que les praticiens publics, privés et des missions pouvaient récupérer leurs honoraires perdus, conformément à un barème convenu. L’article présente une partie des conclusions d’une évaluation de cette politique, sur la base d’entretiens avec 65 informateurs clés dans le système de santé aux niveaux national, régional, des districts et des maternités, notamment des responsables politiques, des gestionnaires et des praticiens. Le mécanisme d’exonération a été bien accepté et était satisfaisant, mais il connaissait de graves problèmes de décaissement des fonds et de maintien du financement, ainsi que de budgétisation et de gestion. La charge de travail du personnel a augmenté car davantage de femmes ont demandé des soins, et les niveaux de compensation pour les services et le personnel étaient importants pour l’acceptation du projet. Fin 2005, un plan national d’assurance maladie, devant couvrir totalement les soins de santé maternelle, démarrait au Ghana et la manière dont le projet d’exonération s’y adapterait n’était pas encore claire.

Resumen

En los países con pocos recursos, el alto costo de las tarifas por partos limita el acceso a asistencia calificada y contribuye a la mortalidad materna y neonatal y al empobrecimiento de hogares vulnerables. En un creciente número de países se está experimentando con diferentes estrategias para afrontar los obstáculos financieros a los servicios de salud materna. En este artículo se describe un plan innovador presentado en Ghana en 2003 para eximir a todas las mujeres embarazadas de pagos por parto, mediante el cual los prestadores de servicios públicos, misioneros y privados pueden reclamar ingresos perdidos de tarifas de usuarias, de acuerdo con una tarifa acordada. Se expone parte de los resultados de una evaluación de la política basada en entrevistas con 65 informantes clave (incluidos formuladores de políticas, administradores y prestadores de servicios) del sistema de salud a nivel nacional, regional, distrital y local. El mecanismo de exención fue bien aceptado y apropiado, pero hubo problemas importantes con el desembolso y sustento del financiamiento, así como con los presupuestos y la administración. El volumen de trabajo del personal aumentó a medida que se atendían más mujeres, y los niveles de remuneración por servicios y personal fueron esenciales para la aceptación del plan. A fines de 2005, se estaba iniciando en Ghana un plan nacional de seguro médico, con el objetivo de incluir cobertura completa de servicios de salud materna, pero aún no era claro cómo el plan de exenciones se integraría a éste.

Key Words:

Barriers to women delivering in health facilities include poor quality services, negative attitudes of health workers, distance to facilities and cultural preferences.Citation1Citation2 Financial barriers have also been important, but there have been relatively few studies of whether and how changing fees influences women’s uptake of maternity services and at what cost.

Most developing countries currently rely on user fees to fund part of their health care. A survey of 16 African countries found that user fees contributed an average of 5% (range 1–20%) of recurrent health service expenditures.Citation3 Although small, this revenue is important, given the problems of low government budgets, unreliable donor aid and poor resource allocation. There is now widespread recognition of the problems caused by user fees, both in terms of inequitable access and inefficiency.Citation4 However, the debate about whether to abolish fees totally and how to replace the lost revenue on a sustainable basis continues. Current discussions focus on the complementary measures which will be needed to ensure that removal of user fees is carried out successfully.Citation5Citation6

If full removal of user fees is considered untenable, there is a case for partial removal of fees for specific services such as maternity care, which have high social priority. Maternity care exemptions would be expected to contribute to reducing maternal mortality (by increasing supervised deliveries) and reducing the impoverishing effect on households of high and unpredictable payments for deliveries (especially complicated deliveries).

This paper describes an innovative scheme introduced recently in Ghana to exempt all women from delivery fees and the findings from the first stage of an evaluation of it, using key informant interviews.

Background

Ghana has persistently high maternal mortality ratios, estimated to range from 214 to 800 per 100,000 live births.Citation7 Ghana also has growing social inequalities for this indicator, with rates of skilled attendance either stagnant or declining for poorer women.Citation8 While deliveries with health professionals rose from 85% to 90% from 1993 to 2003 for the richest quintile, according to Demographic and Health Survey data, deliveries with health professionals for the poorest quintile dropped from 25% to 19%. Nationally, 45% of births were attended by a medical practitioner (79% in urban areas, 33% in rural); 31% by traditional birth attendants (TBAs) and 25% were unsupervised. There were also significant regional variations. The three northern regions have the highest levels of poverty and maternal mortality and the lowest levels of supervised deliveries.Citation9

In the Ghana health system, basic obstetric and antenatal care are provided by health centres, health posts, mission clinics and private midwifery homes. Each health centre or post serves a population of approximately 20,000. In the rural areas, TBAs continue to carry out deliveries, though they are trained to refer more complex cases. Comprehensive emergency obstetric care is available from district hospitals and regional hospitals, as well as national referral hospitals. Most are run by the Ghana Health Services, though the mission sector plays a significant role, especially in more remote regions.Citation7 All care is paid for, unless the service is exempt or the person has private or public health insurance, though user fees are subsidised by public inputs into the services.

Financial barriers are believed to be one of the most important constraints to seeking skilled care during delivery in Ghana.Citation7 A study costing maternal health care in one district in 1999 found cost recovery rates of between 152% for deliveries and 211% for caesareans in mission hospitals, but did not shed light on affordability relative to women’s income.Citation10 Problems such as under-funding of exemptions from user fees in general have also been found,Citation11–13 which have meant that exemptions are available in theory but not always in practice if the provider is not reimbursed for lost income.

The Government of Ghana introduced exemptions from delivery fees in September 2003 in the four most deprived regions of the country, which in April 2005 was extended (without formal evaluation) to the remaining six regions. The aim was to reduce financial barriers to using maternity services to help reduce maternal and perinatal mortality and contribute to poverty reduction.Citation14

The policy was funded through Highly Indebted Poor Country (HIPC) debt relief funds, which were channelled to the districts to reimburse public, mission and private facilities according to the number and type of deliveries they attended monthly. A tariff was approved by the Ministry of Health which set reimbursement rates according to type of delivery (e.g. normal, assisted or caesarean section) and type of facility. Mission and private facilities were reimbursed at a higher rate, because they did not receive public subsidies.Citation14 Women would then only have to bear the costs of reaching facilities.

In 2005, an evaluation by IMMPACT of the free delivery policy was initiated.Citation15 The first stage was based on a series of key informant interviews to establish the state of implementation of the exemption policy and seek the views of stakeholders. These findings fed into the overall evaluation, which included tracking of finance flows, a household survey, a survey of health workers and TBAs, qualitative investigations in communities and among providers, and quality of care assessments. These were completed in 2006.Citation16

The policy of user fee exemptions is now to some extent being superseded by a new National Health Insurance system, which has reached effective coverage of just under 20% of the population.Citation17 This provides protection against user fee costs for a wide range of health services, including maternal health care, for formal sector workers, those in the informal sector who take up voluntary coverage, children of members, pensioners and a small category of “indigents”. However, the delivery fee exemption policy remains in place, officially, at this writing.

Methods

For the evaluation two regions were chosen: one of the four regions to join the exemption scheme first (Central) and the other from the more recent wave (Volta). Six focus districts from each region (roughly half of the districts in each region) were chosen, and matched for population size, poverty status, urban profile and health infrastructure.Citation15

The 65 key informant interviews were conducted from September–December 2005. The key informants included key stakeholders in the Ministry of Health, Ghana Health Services, mission sector and development partnersCitation9; Regional Directors of Health Services, Senior Medical Officers, regional hospital directors and administrators, and regional accountantsCitation7; and District Directors of Health Services and senior public health staff, District Assembly staff and accountants.Citation32 A sample of in-charges, matrons and senior facility staff were also interviewed at facility level.Citation16 The facilities were selected by a process of stratified random sampling, to represent each of the six focus districts and to cover a range of facility types, including district hospitals, health centres, mission hospitals, private maternity homes and mission clinics.

The authors carried out the interviews using a semi-structured questionnaire. The questions covered:

| • | at national level: perceptions of the programme, successes and failures, implementation, allocation of resources, disbursement mechanisms, sustainability and future funding options, priority of the programme, impact on services and staff, interaction with health insurance in future and suggestions for future changes; | ||||

| • | at regional level: similar questions but more detail about the process of establishing the programme, current implementation, adequacy of funding, degree of dissemination in the community and impact on quality of services; | ||||

| • | at district and facility levels: questions were added about dates of operation, whether patients were making contributions of any kind, delays in funding, whether funding can be vired to other uses, appropriateness of reimbursement tariffs, effect on defaulter and referral rates, whether reimbursement covers loss of user fee income, whether revenue is shared with staff in facilities, impact on private midwives (who were meant to be included in the scheme) and TBAs (who were not included but whose business was likely to be affected), whether the scheme was efficient to manage, and other programmes in the district which might affect supervised delivery rates. | ||||

The responses were analysed by topic, level and region and triangulated, where possible, with figures available from facility records or annual reports. The findings were initially presented in an internal report for IMMPACTCitation18 and then in a policy brief.Citation19

For a qualitative process, 65 is a relatively large number and should give findings that are representative for those regions (though not necessarily nationally). Discussions at national level suggest that the findings in these two regions were not exceptional. Findings from such qualitative research need to be set in the context of other data gathering tools, and this is done to some extent in the discussion, comparing findings from interviews with other evaluation component findings.

Findings

Overall perceptions

There was generally a positive reception of the free delivery policy as an effective approach to an important problem, which allowed for early reporting and better handling of complications. Stakeholders within the health system found the administration of the scheme manageable and there was reasonable consistency in the interpretation of the policy. These informants were only able to provide weak evidence on community perceptions, but their view was that communities were both informed and enthusiastic. The scheme was publicised through meetings with traditional rulers, broadcasts and durbars (public meetings) at churches and other public places. The trends in utilisation – both up, when the scheme was functioning, and down, when it stopped - suggested that women were cost-aware and informed about the charging regime.

Availability and adequacy of funding

The main constraints, which were causing concern at all levels, were the shortfalls and unpredictability of funding. Funds were issued at the start of the financial year, without guidance for managers as to how they had been calculated, how long they should last or when they would be replenished. The funds were not adequate for a full year and further instalments were expected but not received until the next financial year.

Managers were used to unpredictable, erratic funding – the norm with previous exemptions, such as for antenatal care, which is routinely in arrears. However, the financial implications of funding not arriving for deliveries were far more serious because they were relatively expensive procedures that had brought in much of the facility revenue.

The failure to reimburse adequately and promptly had negative effects at all levels of the system. Patients, having been told they would receive free services, were reported to be angry when they were asked to pay, and staff were suspected of taking a cut of the funds. Facility staff wondered if the funds had been siphoned off higher up the system. District and regional health managers were caught between facilities accumulating debts and the need to persist with the policy.

“It is difficult to charge now, as people will think you are cheating them. But what do I do when I have no drugs left?”

As a consequence of the funding shortfall, three out of six districts visited in Central Region had reverted to charging, and the others were close to joining them. The regional hospital claimed to have substantial amounts owing from the district funds for referral care provided free. Having provided items on credit, the regional medical store found it could not be reimbursed by districts whose exemption funding had run out. Analysis of funds received in Central in 2005 compared with expected delivery numbers and unit costs suggested that the funds would be adequate only for one-third of the year.

The situation in Volta Region was even worse. The scheme only began in May or June 2005 in most districts, and many had run out of funds by August or even earlier. Facilities were still supposed to be providing free services, but payments were in arrears, it was not clear whether further funds would arrive, and some facilities claimed they had not yet received any reimbursements at all. Four out of six districts visited had run out of funds by early October 2005.

Management problems

A number of management failures were described by national level informants to explain the irregular funding flows. The complexity of funding channels and multiple actors meant that responsibility for the policy was unclear and monitoring weak. In Central Region, for example, the first funding flows in late 2003–early 2004 passed through the District Assemblies (local government bodies). The second tranche in early 2005 passed via the Ghana Health Services in both regions, but the national level claimed not to have been informed of the funding allocations and hence had not issued instructions for their use. In Volta, there was confusion about the funding channels stated in the national guidelines and the actual channel through which funds arrived. In addition, guidelines for monitoring were not enforced. At national level, oversight information on numbers of deliveries carried out and delivery types and reimbursement amounts were not available. In Volta, concerns were expressed that there was no additional funding for the administration of the scheme.

Allocation of funds to districts

The 2004 national guidelines applied a per capita allocation of 1,510 per capita (US$0.17) for the poorer regions (including Central), and a lower rate for the relatively richer regions (including Volta) of 1,354 (US$0.15). However, in practice, there seemed to be some local adjustment. In Central Region, districts with more facilities had received a higher allocation. Despite this, they had exhausted their funds more quickly. An agreed system for funding cross-border patient flows was also needed. This was particularly relevant when the policy was limited to certain regions; women were said to be coming from Accra to deliver in Central, for example, when Accra was not yet included in the policy.

In Volta, funds were allocated on a per capita basis to the districts, with no variation for facility number or size.

“The whole design was poor from the beginning: they didn’t ask the regions how much they needed. We in the region developed our own criteria, based on past utilisation, but we have never received any funds since then.”

Interpretation of the package

In Central Region, the understanding was that the exemption covered deliveries only, but not complications during pregnancy or post-partum. Some suggested that the definition should be broadened to include pregnancy-related complications and also transport costs. In Volta, the regional director also wanted to provide a more inclusive package, but at facility level, the interpretation was restricted to deliveries.

Reimbursement rates

Despite there being a national tariff setting out the reimbursement rates by type of delivery and facility, reimbursement rates were found not to be the same across the two regions. In one region, normal deliveries were paid at a relatively generous rate, but complications and caesarean sections were paid at less than the national rate. In the other, the opposite approach had been taken, with discontent about the rates for normal deliveries, but top-end rates being paid for complicated cases. Satisfaction amongst providers correlated with these differences.

Some mission in-charges in Central were dissatisfied with the payments for more complex deliveries, compared to what they had charged women before. Others were receiving repayment rates well above previously charged user fees. In addition, at least while funds were available for the policy, the facilities did not have to worry about chasing the 25–50% of women who were struggling or unable to pay (particularly for caesareans).

Volta drew up its own reimbursement rates, based on the national guidelines, but also included a provision to pay trained TBAs for deliveries at a lower rate. Of the six districts visited by the research team, only one was including the TBAs, however. Facilities were billing according to materials used, rather than at fixed rates. There was at least one report of inappropriate billing for procedures carried out before the policy was in effect, emphasising the need for vetting and auditing. Key informants in Volta cited lower but still substantial defaulter rates prior to the policy, higher for hospitals than health centres, which find it easier to enforce payment, being closer to households.

Impact on staff

The national guidelines made no mention of incentive payments to staff, but Central Region had agreed a small payment of 20,000 cedis (US$2) for midwives and ancillary staff per delivery. This was justified by the increased workload they faced, as well as lost income from selling small items to women and getting donations from them. Staff and managers appreciated the regularity of the monthly payments from the district when the funding was available, and the fact that they did not have to contend with women who could not pay, who were often detained and whom health staff often helped with their bills. In Volta (and in some of the mission facilities in Central), staff received no direct payments relating to the exemptions policy. They cited income lost from petty sales to women, though it is possible that this was continuing in places.

Quality of care

Changes to quality of care were measured by other evaluation components, but the key informant interviews probed perceptions of changes. The view in Central was that quality was improved by the more reliable funding flows for services, while the policy was adequately funded, even though staff workloads but not staffing levels were increased. In general, the brain drain and issues of retention were the biggest headache faced by managers, though this was a wider issue, not directly related to the exemptions scheme. Tiredness and overload were reported, but most in-charges felt they were still able to cope and had not reached breakdown levels.

Attitudes were less positive in Volta. The staff felt that quality of care was more or less the same, and that workloads were too heavy before and had not been improved. The scheme had not added sufficient extra resources to have had any beneficial effect. Some dissatisfaction was expressed with the quality of services, e.g. with poor use of partograms, and negative attitudes of midwives towards women, but these were not seen as affected by the scheme.

Informal payments

Informal payments by women, an important feature of the health system prior to exemptions, were reported to be diminished or removed in Central Region, where exemptions had been in place for longer. In Volta, which was only just starting the scheme and where financial problems were already apparent, evidence on informal payments was mixed.

Referrals

Given the shortage of medical and nursing staff in Ghana, referrals are often the result of the absence of a key member of staff or of key supplies, such as blood. Under the exemptions policy, women presenting at health centres and district hospitals were eligible for delivery fee exemptions, but attendance at regional hospitals required a referral to qualify. However, there was no formal system for splitting the reimbursement payments between facilities when women were referred. This led to concerns that lower level facilities would fail to refer women at appropriate times in order not to lose the income from their case, as the facility which finally carried out the delivery got the full reimbursement. This was denied by health staff, who pointed to maternal death audits as one way of monitoring this tendency. In practice, some degree of flexibility about reimbursement was found, such that direct costs such as transport, incurred by lower level facilities, could be claimed back, even if the delivery eventually took place elsewhere.

In Central, exemption funds were held by districts, and the regional hospital was experiencing difficulties getting reimbursements from the districts. In Volta, the system operated differently, and 5% of funds were top-sliced to a separate account in advance to pay for referrals. At the time of the research, this fund was still in credit.

Impact on mission and private sectors

The mission sector is increasingly being incorporated into the public health system on a par with public facilities. Thus, mission hospitals and clinics were participating in the exemptions policy, though some smaller clinics complained they had not been well informed. Private midwives were also participating, but their numbers were limited. In some districts in Volta, mission facilities had reportedly opted not to join the scheme as they were dissatisfied with the repayment rates offered.

Prior to the exemptions policy, many mission facilities operated a “poor and sick fund”, which raised funds locally and internationally to pay for those deemed unable to pay. This used to cover about 15–20% of deliveries, according to national level mission informants. If new schemes undermine the old and are not sustained, there will be a net loss to society.

Changes to uptake of services and outcomes

Perceptions of increased utilisation were triangulated with routine reports, where available. These showed different patterns in different districts. For example, in one district in Central, skilled attendance rates, including deliveries by trained (but not untrained) TBAs, had remained constant, but with evidence of a switch to facility-based deliveries. In another district, a big increase preceded the policy and was probably linked to an increase in TBA training. In others, the policy appeared to be linked to increases in facility-based deliveries.

The exemption scheme was felt to have had a very beneficial effect in terms of encouraging women to come in early, so that complications were detected and better managed, saving lives. This was reflected in the increase in more complex interventions. In Gomoa district, for example, there were 86 caesarean sections in 2002; 138 in 2003 and 190 in 2004 (or 1.4%, 2% and 2.6% of supervised deliveries in those respective years). The district hospital in Abura/Asebu Kwamankese also reported a doubling of numbers of caesareans. For Central region as a whole, 3.8% of supervised deliveries were caesareans in 2004. The regional reproductive health report showed a declining trend in facility-based maternal mortality: 450 per 100,000 in 2001, dropping to 206 in 2002, 159 in 2003 and 134 in 2004.

Given the short period of implementation, it was harder to assess changes in utilisation in Volta. Informants reported substantial increases in utilisation (it had doubled, according to the regional director). For specific facilities though, the picture was more mixed. For a private midwife located near a district hospital, it meant the halving of her business, as women could access free services at a better-equipped facility. In one district where funds ran out at the end of June, utilisation, which had increased, was reported to be on the decline again.

Recommendations by informants

Some informants suggested broadening the approach to cover all health care in pregnancy to include, for example, malaria treatment for pregnant women and post-partum care. Others suggested that some transport funds should be added to enable women in remote areas to benefit. However, the main concern was the sustainability of the scheme, and to that end, respondents suggested reducing overall costs by targeting only poor households, targeting only poor regions, only reimbursing deliveries at health centres or, conversely, only reimbursing complicated deliveries (which are least affordable for households), and limiting the number of eligible pregnancies for exemption to two.

“It can end up like the other policies, whereby the first two or three chunks of money come, and later it takes years.”

“Though some will see it as discriminatory, the fact is that some can pay and they must pay to help the system.”

A few informants felt that services should in principle not be free, that Ghana has been moving from a free health service through various stages of cost recovery towards health insurance, that it gives the wrong message to offer totally free services, and that maybe some small co-payment should have been included. It was observed that people pay large amounts for other services, such as prayer camps or scans at private facilities in early pregnancy, and do not value anything they get free.

Relationship to the National Health Insurance Scheme

At the end of 2005, a national health insurance scheme was starting up in Ghana.Citation20 It was not clear to most stakeholders how the exemptions scheme would fit into this new initiative which, in time, was intended to provide full maternal health care cover. Formal sector workers were automatically enrolled, but coverage for the informal sector (the majority of Ghanaians) was voluntary and at low levels. In principle, exemption funds could be re-routed in future to provide free or subsidised cards to pregnant women, but details of this were still under discussion.

Many of the issues highlighted by the review of the exemptions programme are relevant to the health insurance scheme. For example, the mission sector was concerned that reimbursement rates under health insurance would be low and that quality would be compromised, leading to a preference for fee-paying patients. Large increases in attendance were already being reported by mission facilities in some areas where the national health insurance was functional.

The development of national health insurance complicated the process of raising funds and budgeting for exemptions, as there were unrealistic expectations about how quickly health insurance could take over this social protection mechanism. The build-up of formal sector health insurance funds, based on contributions from employees and a levy on VAT payments, also made it harder for the Ministry of Health to argue for continued HIPC funds to pay for delivery exemptions.

Discussion

Ghana’s experience of this scheme is important, given that a growing number of countries are experimenting with different approaches to tackling financial barriers to maternal health care. Nepal, for example, is piloting a policy that combines subsidies for all deliveries with free deliveries and assistance with costs such as transport for women in poorer regions.Citation21Citation22 There is experience in Yunnan, China, and Bangladesh in using vouchers that entitle poor women to free delivery services.Citation23 In Bolivia, a social insurance scheme, which provides free care for pregnant women and under-fives, has increased utilisation, especially by the poor.Citation24 In Senegal, an evaluation is being finalised of a scheme to provide free deliveries and caesareans in all regions outside the capital.Citation25

The decision in Ghana to cover all deliveries, initially within poorer regions and later nationally, reflects awareness of the documented difficulties of individual targeting,Citation26 but it also increased the cost of the scheme. It is debatable whether the decision to extend the scheme to the remaining six regions so quickly was appropriate, given funding constraints and the fact that the first stage had not yet been evaluated. The evaluation of financial flows found that the policy was under-funded by 34% in 2004, rising to 73% in 2005 when all ten regions were covered.Citation27

Analysis of utilisation changes from the household survey, comparing the 18 months before introduction with the 18 months afterward, found an increase of around 12% in women delivering in facilities in Central Region but not in Volta, presumably due to the short period of implementation. It also found significant reductions in mean out-of-pocket payment by patients for delivery care (direct and indirect payments) at health facilities, both for spontaneous vaginal delivery and caesarean section. The total payments for caesareans fell by 21.6% and normal deliveries in health facilities by 18.9%, and there was a reduction in the number of households having to make catastrophic payments for deliveries.Citation16 Other out-of-pocket payments for deliveries remained, but were reduced from 4.78% to 4.15% of household income during the implementation of the policy in these two regions for the poorest quintile, while for the wealthiest quintile, they fell from 3.3% to 2.59%. Given the relatively high cost-recovery rates in Ghana and reasonable geographic access to services, the emphasis on reducing fees was appropriate, whereas in Nepal, transport costs constitute the largest cost element for households in accessing maternal care.Citation22

Ghana’s experience suggests that where facilities are understaffed, as in much of sub-Saharan Africa, they should be closely involved in the development of policies such as these and a package of incentives provided for staff to deliver quality care. The health worker survey in this evaluation found that although very few direct financial incentives were provided as part of the delivery exemption policy, the overall increase in pay as part of wider pay reforms in the public sector compensated for increased hours of work for different types of staff.Citation28

Qualitative work with midwives and communities suggests that comprehension of the policy was not always strong,Citation29 highlighting the need for clear, simple designs and better communication.

The impact on maternal mortality has not been established, but case note extraction in a sample of hospitals and routine data collected in health centres indicated that quality of care was unchanged on the whole, and poor,Citation16 e.g. routine monitoring of labour in hospitals occurred in only 31% of cases.

International reviews of waivers and exemptions have already noted the importance of providing funding to reimburse facilities for revenue lost so that they have a strong incentive to offer exemptions.Citation30Citation31 Ghana’s experience corroborates that: user fees have been increasing in recent years and amounted to 26% of Ghana Health Services income in 2003.Citation32 At the facility level, internally generated funds constitute the main source of flexible funding for drugs, supplies and other minor purchases which are essential to the running of services. Because maternal health care is an important income-generating activity for facilities.Citation10 exemptions or a health insurance scheme will need to offer payments that reflect those costs, without rewarding inefficiency and taking into account the various subsidies which different facilities already receive.

Ghana has been bold in including the mission sector, private midwives and even, in some areas, TBAs in its scheme. The issue of which type of providers should be included should be a pragmatic issue, however, reflecting cost, quality and coverage. There are equity and efficiency arguments for including TBAs: they work in more remote communities, where women may not be able to reach facilities, even if deliveries were free; they are less costly to reimburse; and there are often strong cultural preferences for home deliveries. There is a strong case for including those whose quality of care is good and whose referrals are appropriate and timely.

Anecdotal evidence suggests that the findings in Central and Volta regions were typical of other regions. One informant said the scheme had more or less come to a halt nationally. There were also reports that delivery fees were being exempted in some areas, but that this was now interpreted narrowly, so that items such as drugs, food, bed nets and admission costs were being charged again.

Conclusion

Underlying the specific budgeting and management problems noted by the stakeholders in Ghana are the more general issues of overloaded systems and poor capacity, which any kind of additional vertical programme exacerbates. The exemptions policy, while not separate in terms of service delivery, had a separate funding channel and reporting requirements, and to that extent added to the workload of struggling officials. The detailed design and management of this kind of scheme is critical to its success, and there is a need for improved communication, both vertically within the health system and across regions, so that the policy can be reviewed and adapted in light of successes and failures. Strong national leadership is also a critical element in sustainability. The experience of Ghana shows the potential of schemes to increase skilled attendance by reducing the costs of services to users, though also some of their most common pitfalls in terms of sustaining commitment and funding.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the support of the research team in the Noguchi Institute for Medical Research, University of Ghana, and the University of Aberdeen, in particular Margaret Armar-Klemesu, the Country Technical Partner leader. Thanks also to the key informants for their generous donation of time to share their views with us, and also to those who commented on the paper, especially Tim Ensor. This work was undertaken as part of an international research programme, IMMPACT (Initiative for Maternal Mortality Programme Assessment), funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, Department for International Development, European Commission and USAID. The funders have no responsibility for the information provided or views expressed in this paper. The views expressed herein are solely those of the authors.

References

- B Amuti-Kagoona, F Nuwaha. Factors influencing choice of delivery sites in Rakai district of Uganda. Social Science and Medicine. 50(2): 2000; 203–213.

- R Wagle, S Sabroe, B Nielsen. Socioeconomic and physical distance to the maternity hospital as predictors for place of delivery: an observation study from Nepal. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth. 4(8): 2004

- L Gilson. The lessons of user fee experience in Africa. Health Policy and Planning. 12(4): 1997; 273–285.

- S Witter. An unnecessary evil? User fees for health care in low income countries. 2005; Save the Children: London.

- M Pearson. Assessing the case for abolishing user fees: lessons from the Kenya experience. 2005; HLSP: London.

- L Gilson, D McIntyre. Removing user fees for primary care in Africa: the need for careful action. BMJ. 331: 2005; 762–765.

- UNFPA, Ministry of Health. Ghana health sector five year programme of work (2002–2006) - an in-depth review of the health sector response to maternal mortality in Ghana by 2003. 2004; UNFPA/MoH: Accra.

- W Graham. Poverty and maternal mortality: what’s the link? Keynote address delivered at Annual Research Meeting, Noguchi Memorial Institute for Medical Research, University of Ghana, Legon. 2004

- World Bank. Ghana Living Standards Survey. 1999; World Bank: Washington DC.

- A Levin. Cost of maternal health care services in South Kwahu district, Ghana. 1999; Partnerships for Health Reform/Abt Associates: Bethesda, MD.

- C Waddington, K Enyimayew. The impact of user charges in Ashanti-Akim district, Ghana. International Journal of Health Planning and Management. 4: 1989; 17–47.

- B Garshong, E Ansah, G Dakpallah. “We are still paying”: a study on factors affecting the implementation of the exemptions policy in Ghana. 2001; Health Research Unit, Ministry of Health: Accra.

- F Nyonator, J Kutzin. Health for some? The effects of user fees in the Volta region of Ghana. Health Policy and Planning. 14: 1999; 329–341.

- Ministry of Health. Guidelines for implementing the exemption policy on maternal deliveries. 2004; Ministry of Health: AccraReport No. MoH/Policy, Planning, Monitoring and Evaluation-59

- Noguchi Institute, IMMPACT. An evaluation of the policy of universal fee exemption for delivery care: Ghana operational protocol. 2005; Noguchi Institute/IMMPACT: Accra.

- M Armar-Klemesu. An evaluation of Ghana’s policy of universal fee exemption for delivery care: preliminary findings. 2006; IMMPACT: Aberdeen.

- R Dubbledam, S Witter. Independent Review of Programme of Work 2006. 2007; Ministry of Health: Accra.

- S Witter, T Kusi, S Zakariah-Akoto. Evaluation of the free delivery policy in Ghana: findings from key informant interviews. 2005; IMMPACT: Accra/Aberdeen.

- IMMPACT. Policy brief: implementation of the free delivery programme in Ghana. 2005; IMMPACT: Aberdeen/Accra.

- Ministry of Health. National Health Insurance Policy Framework for Ghana (revised version). 2004; Ministry of Health: Accra.

- T Ensor. Cost sharing system for alleviating financial barriers to delivery care: review of the proposed scheme. 2005; Options: London.

- J Borghi, T Ensor, B Neupane. Financial implications of skilled attendance at delivery in Nepal. Tropical Medicine and International Health. 11(2): 2006; 228–237.

- D Kelin, Z Kaining, T Songuan. A draft report on mother and child health: Poverty Action Fund study in China. 2001; World Bank: Washington DC.

- T Dmytraczenko, I Aitken, S Carrasco. Evaluation of the national security scheme for mothers and children in Bolivia. 1998; Abt Associates for PHR: Bethesda MD.

- Ministry of Health IMMPACT UNFPA Centre de Formation et de Recherche en Santé de la Reproduction. An evaluation of the policy of fee exemption for deliveries and caesareans in Senegal: operational protocol. 2006; IMMPACT: Aberdeen.

- L Gilson, S Russell, K Buse. The political economy of user fees with targeting: developing equitable health financing policies. Journal of International Development. 7(3): 1995

- S Witter, M Aikins, T Kusi. Funding and sustainability of the delivery exemptions scheme in Ghana. 2006; IMMPACT: Aberdeen.

- S Witter, A Kusi, M Aikens. Working practices and incomes of health workers: evidence from an evaluation of a delivery fee exemption scheme in Ghana. Human Resources for Health. 5(2): 2007

- D Arhinful, S Zakariah-Akoto, B Madi. Effects of free delivery policy on provision and utilisation of skilled care at delivery: views from providers and communities in Central and Volta regions of Ghana. 2006; IMMPACT: Aberdeen/Accra.

- R Bitran, U Giedion. Waivers and exemptions for health services in developing countries. 2003; World Bank: Washington DC.

- M Tien, G Chee. Literature review and findings: implementation of waiver policy. 2002; Abt for Partnerships for Health Reform Plus: Bethesda, MD.

- Ghana Health Service. GHS 2003 Performance Report. 2004; GHS: Accra.