Abstract

Evidence gathered from 1997 to 2006 indicates progress in reducing maternal mortality in Nepal, but public health services are still constrained by resource and staff shortages, especially in rural areas. The five-year Support to the Safe Motherhood Programme builds on the experience of the Nepal Safer Motherhood Project (1997–2004). It is working with the Government of Nepal to build capacity to institute a minimum package of essential maternity services, linking evidence-based policy development with health system strengthening. It has supported long-term planning, working towards skilled attendance at every birth, safe blood supplies, staff training, building management capacity, improving monitoring systems and use of process indicators, promoting dialogue between women and providers on quality of care, and increasing equity and access at district level. An incentives scheme finances transport costs to a health facility for all pregnant women and incentives to health workers attending deliveries, with free services and subsidies to facilities in the poorest 25 districts. Despite bureaucracy, frequent transfer of key government staff and political instability, there has been progress in policy development, and public health sector expenditure has increased. For the future, a human resources strategy with career paths that encourage skilled staff to stay in the government service is key.

Résumé

Les données recueillies de 1997 à 2006 indiquent des progrès dans la réduction de la mortalité maternelle au Népal, mais les services de santé publique sont encore limités par les pénuries de ressources et de personnel, particulièrement dans les zones rurales. Le Programme quinquennal de soutien à une maternité sans risque est fondé sur l’expérience du Projet népalais de maternité à moindre risque (1997–2004). Il travaille avec le Gouvernement népalais pour créer un ensemble minimum de services essentiels de maternité, en liant la définition de politiques à base factuelle au renforcement des systèmes de santé. Il a soutenu la planification à long terme, les activités pour que tous les accouchements bénéficient d’une assistance qualifiée, un approvisionnement sanguin sûr, la formation du personnel, la consolidation des capacités de gestion, l’amélioration des systèmes de suivi et l’utilisation d’indicateurs de processus, la promotion du dialogue entre les femmes et les prestataires sur la qualité des soins, et l’accroissement de l’équité et de l’accès au niveau des districts. Un plan finance les frais de transport de toutes les femmes enceintes jusqu’à un centre de santé et des primes d’encouragement pour les agents de santé qui supervisent les accouchements, avec des services gratuits et des subventions pour les équipements des 25 districts les plus pauvres. Malgré la lourdeur de la bureaucratie, les transferts fréquents de fonctionnaires clés et l’instabilité politique, la définition des politiques a progressé et les dépenses de santé publique ont augmenté. Pour l’avenir, une stratégie de ressources humaines avec des plans de carrière qui encouragent le personnel qualifié à demeurer dans le secteur public est capitale.

Resumen

La evidencia reunida desde 1997 hasta 2006 indica avances en la disminución de la mortalidad materna en Nepal, pero los servicios de salud pública aún se ven limitados por la escasez de recursos y personal, especialmente en las zonas rurales. El programa de Apoyo a la Maternidad Sin Riesgos, de cinco años de duración, se basa en la experiencia del Proyecto de Maternidad sin Riesgos (1997–2004), en Nepal. Está trabajando con el Gobierno nepalés a fin de desarrollar la capacidad para instituir un paquete mínimo de servicios esenciales de maternidad, vinculando la formulación de políticas basada en evidencia con el fortalecimiento del sistema de salud. Ha apoyado la planificación de largo plazo, procurando tener asistencia calificada en cada parto y suministros seguros de sangre, capacitando al personal, desarrollando la capacidad de administración, mejorando los sistemas de monitoreo y el uso de indicadores del proceso, fomentando diálogo entre las mujeres y los prestadores de servicios sobre la calidad de la atención, y aumentando la equidad y el acceso a nivel distrital. Una estrategia de incentivos financia los costos de transporte al establecimiento de salud para todas las mujeres embarazadas y los incentivos para que los trabajadores de la salud asistan en los partos, con servicios gratuitos y subsidios para los establecimientos en los 25 distritos más pobres. Pese a la burocracia, al traslado frecuente de personal gubernamental clave y a la inestabilidad política, ha habido avances en la formulación de políticas, y los gastos del sector salud pública han aumentado. En el futuro, es indispensable una estrategia de recursos humanos con trayectorias profesionales que motiven al personal calificado a continuar trabajando para el gobierno.

Support to the Safe Motherhood Programme (SSMP), funded by the UK Department for International Development (DFID) and managed by Options UK, was initiated in 2004 as a five-year agreement with the Government of Nepal. It is designed to support the national Safe Motherhood Programme and complement the DFID Health Sector Reform Support Programme. SSMP builds on experiences from the Nepal Safer Motherhood Project (1997–2004) but differs significantly, moving from a district-focused project to a programme approach, working directly with and through the government to build capacity and develop systems, based on the national goals and logical framework. Inputs are designed in collaboration with the Ministry of Health and Population in order to ensure they meet national needs. Financial aid is paid directly to the government, with technical assistance provided through a core team of centrally-based advisers and five implementing partners responsible for focused activities in selected districts, which feed into central planning and advocacy.

The 2006 Nepal Demographic and Health SurveyCitation1 showed a reduction in the maternal mortality ratio from 539 per 100,000 live births in 1997Citation2 to 281. This has provided a tremendous boost to the national Safe Motherhood Programme and partners. Since its inception in 1997, the national Programme has focused on improving the availability, quality and utilisation of emergency obstetric care in district hospitals, to address the needs of the estimated 15% of pregnancies likely to develop serious complications,Citation3 which account for 70% of maternal deaths in Nepal.Citation4Citation5 A range of external agencies have supported staff training, infrastructure and equipment, behaviour change interventions promoting antenatal, skilled delivery and post-partum care, and community emergency funds and transport schemes. As a result, between 1996 and 2006, utilisation of antenatal care services increased from 39% to 72%, delivery by a trained health worker from 9% to 19%, institutional delivery from 8% to 18% and caesarean sections from 1% to 2.7%.Citation1 Abortion was legalised in 2002 and safe services (public, private and NGO) are now available in 70 of the 75 districts, with over 80,000 women accessing them between April 2004 and December 2006. This has reduced the risk of deaths due to unsafe abortions, although it is still too early to see a significant effect on the figures. Perhaps most importantly of all, the lifetime risk of maternal death declined by 33% between 1996 and 2006, as the total fertility rate declined from 4.6 to 3.1.Citation1 Further analysis has been commissioned on some of these key issues.

Despite this encouraging progress, public health services are still constrained by resource and staff shortages, especially in rural areas, where 83% of the population live.Citation5 A recent survey undertaken by UNICEF in eight SSMP/UNICEF-supported districts showed staffing levels of posts for doctors and nurses of only 50–60% as the norm, even in district hospitals, with the situation considerably worse in peripheral facilities.Citation6 Services are often perceived to be of poor quality and do not meet women’s needs, as evidenced in a recent study by the Save the Children US Access programme,Citation7 which found that women were not utilising services for this reason, preferring a home birth except in extreme emergencies. Lack of knowledge and finance are also significant barriers to accessing services, especially among poor and socially excluded families, and pro-poor targeting of demand creation is essential to ensure that improved services do not benefit only the better off and those living close to facilities.

An integrated package of support

Efforts to improve emergency obstetric care have been increasingly complemented by involvement of communities and local NGOs in promoting access to and demand for services, and a focus on social inclusion to reach marginalised communities. Promotion of delivery by skilled birth attendant, rather than health worker, is another important development. Perhaps most significant has been recognition of the importance of a functioning overall health system to support safe motherhood efforts. This is reflected in SSMP’s close links with the DFID Health Sector Reform Support Programme, through which SSMP can act as a pilot and an indicator for whole sector approaches,Citation8 and health sector reform efforts can support safe motherhood programming through critical areas such as human resource management.

Support to the Safe Motherhood Programme provides an integrated package of technical support in six key areas:

| • | policy development and planning, | ||||

| • | service strengthening, including infrastructure, technical and management improvements, | ||||

| • | human resources development, particularly for skilled birth attendants, | ||||

| • | increasing equity and access, | ||||

| • | financing demand creation, and | ||||

| • | monitoring and information management. | ||||

Policy development

SSMP is working with other safe motherhood stakeholders to support significant policy and planning developments as a foundation to the national programme:

| • | Development of the revised National Safe Motherhood and Newborn Health Long-Term Plan, 2006–2017.Citation9 | ||||

| • | Revision of the National Blood Policy in 2006 and work with the Nepal Red Cross Society and National Blood Laboratory to develop guidelines and provide training to ensure the availability of safe blood at district hospitals providing emergency obstetric care.Citation10 | ||||

| • | Support for the integration of abortion as an essential safe motherhood service under the National Safe Abortion Policy, 2002Citation11 that legalised abortion up to 12 weeks of pregnancy. | ||||

| • | The SSMP draft Social Inclusion StrategyCitation12 is at final discussion stage and will be used to influence health sector reform and government policy development. It reflects the need to target the poor and excluded, as recent data show that access to safe motherhood services is strongly affected by caste and ethnicity. This strategy is timely as recent political developments in Nepal place social inclusion at the heart of a new national reform agenda, challenging deeply rooted attitudes and practices. | ||||

| • | Development of the National Policy for Skilled Birth Attendants 2006,Citation13 which embodies a commitment to skilled attendance at every birth, whether at home or in a facility.Citation14 Nepal is one of the few developing countries to have such a policy. | ||||

| • | Preparation of a draft strategy for maintenance of health infrastructuresCitation15 to ensure facilities are fit to provide quality services and to reduce wastage. | ||||

Strengthening services

To improve the quality of obstetric care, the Nepal government and partners have developed a minimum package of essential maternal and newborn health services to be provided at different health facility levels, which meets the WHO criteria for evidence-based careCitation16Citation17 and addresses the causes of maternal death. The document specifies the services, staffing and equipment expected at each level of health facility and integrates newborn care, safe abortion and prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV with safe motherhood services, optimising use of resources and providing a national standard.

SSMP is working with the government to develop a cost-effective approach to improving services in districts that do not have project support. Based on the “appreciative inquiry” techniques used in the Nepal Safer Motherhood Project districts,Citation18 this approach aims to empower health facility management committees and communities to take responsibility for improving local services. It focuses on positive achievements rather than gaps and failings, with the aim of creating a belief in the power to change, and working with participants to identify changes needed and ways to achieve them. It has been successfully piloted in one district and modalities for scaling it up are being developed.

The pilot, Lahan hospital, serves a densely populated plains district (population 569,880Citation19), with a large number of poor and disadvantaged communities. As a busy referral centre for several neighbouring districts, its essential obstetric care facilities are being upgraded. However significant gaps were noted in the quality of care provided, such as poor infection prevention and waste disposal practices, overcrowded service and waiting areas with sub-optimal patient flow arrangements, erratic staff attendance and emergency drug supplies not maintained. As a result, the reputation of the hospital and relations with the local community were not good.

The process began with a needs assessment in December 2005,Citation19 followed in May 2006 by a planning workshop jointly organised by the local health authority and facility management committee. It was facilitated by a professional experienced in appreciative inquiry, with technical inputs from SSMP and central government staff. The technical sessions helped to increase the understanding about maternal and newborn health among management and community participants and gain their support. Local participants included representatives from civil society, political parties, local media, development programmes and health workers. They were guided to use the findings of the needs assessment and technical inputs to develop a six-month plan for ensuring 24-hour quality obstetric care services. This covered infrastructure, equipment, staff training, management and community relations, with activities ranging from cleaning the hospital surroundings and managing patient flow, to renovating service rooms, improving waste management and disposal systems, and establishing subsidy systems.

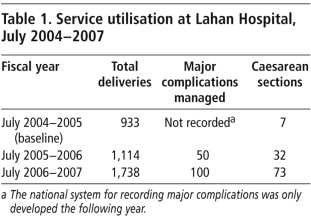

At a second review and planning workshop, three months later, achievements were reviewed and plans adjusted for the next phase, including rolling out the process to peripheral facilities. During the first year of the pilot, the package has proved practical and flexible, facilitating major positive changes, both tangible and less tangible.Citation20 Some, such as improvements in surgical facilities, were initiated immediately after the needs assessment, stemming from the sense that support was available. Later improvements included better infection prevention and waste disposal practices and improved overall cleanliness, regularly maintained supplies of emergency drugs and equipment, use of the partograph and improved layout of the labour room for privacy. Human resource management has improved and the hospital management committee recruited additional staff from its own budget. Patient flow and social relations have improved, with a new layout of the reception area and the receptionist making patients feel more welcome. Subsidies and free services are available for the poor. As a result, hospital records show a significant increase in service utilisation, as shown in Table 1.

Having broken out of a cycle of poor services, poor reputation and low utilisation, the hospital has more women using services, more support from the community, better management and higher staff morale, enabling it to continue to improve, with only minimal external inputs from regionally based monitoring and support staff.

A small team of consultants, led by the pilot facilitator with support from the government and SSMP, has begun implementing the package in a further 13 facilities in seven districts. These were prioritised to complement the demand creation inputs of the SSMP equity and access programme in these districts. In the next phase, emergency obstetric care facilities receiving support for new buildings or significant renovations will be targeted to enable them to maximise these inputs to improve services.

Skilled birth attendance

Increasing skilled attendance at birth is an essential component of safe motherhood programming.Citation14 In Nepal it has been agreed that a doctor, nurse or auxiliary nurse-midwife who has received standard training in the internationally defined set of core midwifery skillsCitation21 qualifies as a skilled birth attendant. In the drive to achieve the Millennium Development Goal of reducing maternal mortality by three quarters by 2015, Nepal has set the target of 60% of all births assisted by a skilled birth attendant.Citation22 In reality, this is probably an unreachable goal, involving the in-service training of over 4,000 staff in less than five years and revision of pre-service courses. Key issues are the shortage of health staff, especially in rural areas, and low service utilisation. Currently only 23.4% of births are attended by any kind of health worker,Citation23 and not all health workers can qualify as skilled birth attendants.

The draft in-service training strategyCitation24 uses a standard learning resource packageCitation25 as the foundation for training curricula for different health cadres. A team of trainers has been prepared, three out of a planned 20 training sites have been updated and the first batches have received training. Concurrently work is ongoing to incorporate training for skilled birth attendants into pre-service courses for doctors and certificate nurses. A multi-partner forum, jointly chaired by the National Health Training Centre and Family Health Division, provides technical and strategic planning support for training, acts as an advocacy body and will guide the development of an integrated strategy covering deployment and support of trained skilled birth attendants and information dissemination to promote utilisation of their services. A holistic approach is essential for rational management of this critical resource and must be linked to sector wide reform to address human resource shortfalls.

In the Nepalese context of remote areas with poor communications, skilled attendance for home deliveriesCitation26 or in local birthing centres staffed by nurse-midwivesCitation27 is recognised as a realistic approach to preventing and managing complications. SSMP is supporting a government programme to design and build community birthing centres attached to health posts. The first of these are under construction and should be staffed by at least two trained nurses to provide 24-hour services. To address human resource shortages, facility management committees are encouraged to use their own funds to hire additional nursing staff, and some have already done so. In SSMP-supported districts, communities are involved in the management and improvement of local facilities, to encourage women to trust them to meet their needs, both for normal births and as a first step in seeking emergency care. This is intended to overcome the tendency observed during the Nepal Safer Motherhood Project of families delaying the decision to seek emergency care and bypassing lower level facilities when the situation becomes urgent.

Increasing access

Evidence shows that service availability alone is not sufficient to increase utilisation and reduce maternal mortality.Citation28 The Equity and Access Programme, based on a scoping study in 2005,Citation29 has been implemented for a year in eight selected districts, and is an essential component of SSMP. The rights-based conceptual frameworkCitation30 aims to increase knowledge, empower women and their families to access and demand services, build the capacity of community organisations and management committees to plan and implement local activities, and support local stakeholders to instigate service improvements and advocate for broader reforms. Social inclusion is woven into the programming at every step. For example, affirmative action principles have ensured recruitment of women and representatives of different ethnic groups to staff the programme, increasing its acceptability and credibility at community level. Demand creation works in tandem with service strengthening activities, to avoid problems caused by creating demand for services that do not exist and to empower communities to lobby for the establishment of services as their right.

Since experience shows that development interventions often benefit the already relatively advantaged,Citation31 pro-poor targeting is an integral part of activities. The target areas have been selected on the basis of having a high population of socially excluded castes and ethnic groups, remoteness and poverty. Social mobilisation activities, such as community meetings, street dramas, financing and transport schemes, thus directly target the disadvantaged as the majority population of the area. Emergency funds and transport schemes use money from village development committees and savings groups. Behaviour change communication interventions are based on the national standard content and messages, but “localised” by the development of local versions of materials and radio programmes, using local languages and culturally appropriate illustrations. Transport schemes are similarly localised, e.g. bicycle ambulances in plains areas and dokas (large baskets carried on the back of a porter) in the hills. The local NGO partners work with health service providers and community influentials to address social barriers and attitudes that may discourage poor and socially excluded women from accessing services.

Two local NGOs have been contracted to undertake regular interviews by specially trained local women with local women, using non-personalised techniques to encourage honest communication about local issues and perceptions,Footnote* exit interviews with women who have received health services, and interviews with service providers. The findings are shared in constructive ways, enabling stakeholders to develop locally appropriate solutions. After only one round of such activities, bringing together service users and providers has resulted in, for example, health staff working their full hours, providing clear information about services and being more polite and respectful to patients. In the next round, this experience will be used to influence central policy development.

Demand-side financing

SSMP is supporting a Maternity Incentives SchemeCitation32 to address financial barriers to women accessing maternity services, which was initiated by the Nepal government in all 75 districts of the country in August 2005. It creates an incentive to deliver in a health facility by covering transport costs for all pregnant women and providing free services for women in 25 low Human Development Index districts. There are also financial incentives for service providers assisting deliveries, either at home or in a health facility, to encourage them to provide services. In the 25 most disadvantaged districts, a facility subsidy for each birth helps fund improvements in services. Figures returned from the districts (90% returned data in 2007) show that 52.5% of the funds were paid to women, 45.4% to service providers and 2.1% to institutions.

This is an ambitious scheme, which poses complex management and information dissemination problems, especially as it was initiated in all 75 districts of the country at the same time. A major challenge is ensuring that the most needy women know about the incentives, as they are likely to live furthest from a health facility and be the hardest to reach with information. Another challenge is establishing watertight systems for financial management, ensuring women are paid at the time of discharge from the facility, with proper recording. After the first year of implementation, initial findings from an independent evaluation through the Institute of Child Health in LondonFootnote* indicated that district managers were confused about the scheme and practices varied considerably. In response, the Family Health Division devoted a full day at each of the five regional reviews (May 2007) to explaining the scheme and listening to feedback from district representatives. This resulted in changes to the policy, implementation guidelines and reporting formats, simplifying and clarifying the process.

Although it is still early days, the scheme appears to be encouraging more women to use a health worker to assist at delivery or to have an institutional delivery. While changes cannot be solely attributed to the incentives, there was a noticeable increase in the overall trend of more deliveries being attended by a health worker in the year after the scheme began. Official figures show an increase of 3.2% (from 20.2% to 23.4%) nationally compared with 2.0% in each of the previous two years.Citation23 Footnote†

Demand-side financing for essential obstetric care is a new concept in Nepal and the availability of national and international evidence is limited.Citation33 Good hospital leadership and proper briefing of district managers about safe motherhood issues and the incentives are critical to ensure the scheme is locally understood, effectively managed and well publicised. Experiences to date indicate that, properly implemented, the scheme can increase service utilisation and hopefully prevent maternal deaths. There is also a case for considering free services, which have been successfully implemented in Uganda.Citation34 This could be of greater financial benefit to women than service fees offset by incentives, and reduce administrative costs and complexity. However, it would markedly increase costs to the health system and might cause such rapid increase in demand for services that quality of care would suffer.Citation34 It is internationally acknowledged that further study is required to fully assess the comparative advantages of the two approaches.Citation35

Monitoring and data collection

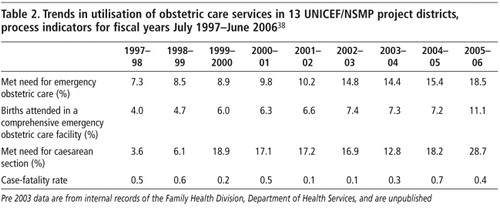

In Nepal, four key process indicators have been monitored since 1997 in 13 of the 75 districts that have received project support, either through the Nepal Safer Motherhood Project or UNICEF. The indicators include three of the six WHO/UNICEF/UNFPA process indicatorsCitation36Citation37 and met need for caesarean section, as this is more effectively demonstrated graphically than percentage of caesareans, which will always be very low. The indicators are: percentage of births at an essential obstetric care facility (normal plus complicated), met need for emergency obstetric care (complications managed, against an expected 15% complication rate), met need for caesarean section and case-fatality rate. Table 2 shows a trend of gradual increase in service utilisation in the 13 districts,Citation38 as measured with these process indicators, from July 1997 to June 2006, with the average case-fatality rate remaining below the 1% level considered acceptable for quality services.

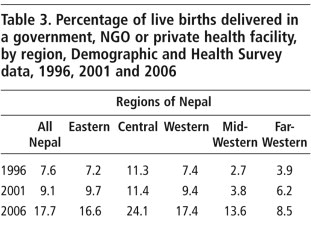

These trends are consistent with a decrease in maternal deaths. Some contributing factors lie outside the health sector, such as improved education levels,Footnote** but coverage of maternal health services, which has a direct effect, has increased, even in the poorer Mid-and Far-Western regions, as evidenced by three Demographic and Health Surveys, shown in Table 3.

These data demonstrate the value of monitoring service delivery indicators. SSMP is supporting the institutionalisation of process indicators into the national Health Management Information System, including development of tools and training to move responsibility for data collection and analysis from projects to the government system. In fiscal year 2006–07, 11 additional districts began sending in these data and more districts will join the scheme in 2007–08. All health facilities providing essential obstetric care throughout the country will receive training to ensure collection of complete data. Disaggregation of data by caste and ethnicity will be an essential feature, to ensure that programmes are implementing socially inclusive policies.

Discussion

National government and civil society efforts have brought about the changes in maternal mortality and in health service delivery and many external development partners have supported them. Until recently the assumption among development aid actors was that the key to sustainability lay in encouraging developing country governments to earmark funding from national sources to scale up successfully piloted project interventions. However, it is now acknowledged that fragile states such as Nepal require continuing financial support to enable them to guarantee the uninterrupted high quality health services encompassed by the concept of a sustainable health service. SSMP has begun to scale down its technical assistance, but the flow of financial aid from DFID will continue. The 2006 DFID White Paper on reducing maternal mortalitiesCitation39 talks of aiming for at least half of all future UK direct support for developing countries to target public services, such as health, education, water and social protection, encouraging other donors to commit to similar long-term, predictable funding support. At country level, advocacy is needed for increased spending on health and can achieve results, especially when there is public support for it.Citation40 For the year 2006–07 only 6.4% of Nepal’s total expenditure was allocated to health, which is about half that spent on education. The current Nepal Health Sector Plan aimed for 7% by 2009. Internal and external advocacy and lobbying resulted in an increase to 7.2% for 2007–08 with a recommended goal of 10%.Citation41

There has been encouraging progress, despite the limitations of complex bureaucratic systems, frequent transfers of key government staff and political instability, the result of Nepal’s current state of emerging democracy after ten years of violent conflict. Unpredictable and sometimes violent protests from various sectors of society, political uncertainty and caution among government decision-makers about upsetting interest groups are a constant source of delay. For example, agreement on the skilled birth attendance training strategy has been delayed by opposition from paramedical staff who are not eligible to become skilled birth attendants, and who fear the erosion of their role and status. Shortage of skilled professionals in rural areas, especially doctors with surgical skills and experienced staff nurses, remains a major constraint, exacerbated by lack of systematic planning for training, deployment and support of these key staff. Despite these challenges, substantial achievements in policy and planning provide a foundation on which the government can build future work. The long-term Safe Motherhood and Newborn Health Plan will guide programming until 2017; joint planning between the government and major external partners has been initiated and the skilled birth attendant and blood policies represent significant developments.

Wider health sector reforms are essential if the gains made in safe motherhood are to be maintained and built upon, as many of the challenges are rooted in the overall health sector. For example, human resource limitations require a holistic human resource management strategy with career paths that will encourage skilled staff to stay in government service. Long-term success lies in enhanced ability of the Nepal government to use this money effectively to build on achievements and work collaboratively with its partners to continue to make motherhood safer in Nepal.

Acknowledgements

The SSMP implementing partners are: ActionAid Nepal, managing the Equity and Access Programme in selected districts; Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health/Centre for Communication Programs, providing technical support for behaviour change communication interventions; the Technical Committee for Implementation of Comprehensive Abortion Care, supported by Ipas; United Mission to Nepal and UNICEF, strengthening services in selected districts.

Notes

* This technique, known as Key Informant Monitoring, was successfully used by the Nepal Safer Motherhood Project.

* Full report not yet available.

† Without statistical testing, these figures can only be taken as a positive indicator and trend.

** Literacy was 51.2% for women over the age of six in 2006, up from 39.5% in 2001, according to the 2001 and 2006 Nepal Demographic and Health Surveys.

References

- Ministry of Health and Population/New Era/Macro International. Nepal Demographic and Health Survey 2006. 2007; MOH: Kathmandu.

- A Pradhan, RH Aryal, G Regmi. Nepal Family Health Survey 1996. 1997; Kathmandu Ministry of Health.

- D Maine, M Akalin, M Ward. The design and evaluation of maternal mortality programmes. 1997; Centre for Population and Family Health, School of Public Health, Columbia University: New York.

- LR Pathak, DS Malla, A Pradhan. Maternal Mortality and Morbidity Study. 1998; Ministry of Health: Kathmandu.

- National Planning Secretariat. Population Projection for Nepal 2001–2021. 2003; Ministry of Health and Population, HM Government of Nepal: Kathmandu.

- UNICEF/Support to the Safe Motherhood Programme. District needs assessment (draft). 2006; UNICEF Nepal: Kathmandu.

- MD Dixit, RA Miller, M Taylor. Utilisation of rural delivery services in six districts: a qualitative study. 2006; Access/Save the Children US: Baltimore.

- Department for International Development. Reducing Maternal Deaths: Evidence and Action. 2004; DFID: London.

- Ministry of Health and Population. National Safe Motherhood and Newborn Health Long-Term Plan, 2006–2017. 2006; MOHP: Kathmandu.

- Ministry of Health and Population. Revised National Blood Policy. 2006; MOHP: Kathmandu.

- Ministry of Health. National Safe Abortion Policy and Strategy. 2002; MOH: Kathmandu.

- Support to the Safe Motherhood Programme. Social Inclusion Strategy (draft). 2007; SSMP Nepal: Kathmandu.

- Ministry of Health and Population. National Policy on Skilled Birth Attendants. 2006; MOHP: Kathmandu.

- MR Campbell Oona, W Graham. Strategies for reducing maternal mortality: getting on with what works. Maternal Survival Series 2. Lancet. 368: 2006; 1284–1299.

- Ministry of Health and Population Department of Health Services Management Division. Maintenance strategy for infrastructures in the health sector (buildings and support services). June. 2007 Kathmandu

- WHO/UNFPA/UNICEF/World Bank. Managing Complications in Pregnancy and Childbirth: A Guide for Midwives and Doctors. 2003; WHO: Geneva.

- WHO/UNFPA/UNICEF/World Bank. Pregnancy, Childbirth, Post-Partum and Newborn Care: A Guide for Essential Practice. 2006; WHO: Geneva.

- R Hodgson, P Khati, K Badu. Artistry of the Invisible: Evaluation of “Foundation for Change” – a Change Management Process. 2003; Nepal Safer Motherhood Project/Options/DFID and Family Health Division, Ministry of Health, Nepal: Kathmandu.

- Sansthaagat Bikas Consultancy Kendra. Need assessment of Shree Ram Kumar Sarada Uma Prasad Muraka Memorial Hospital, Lahan, Siraha District, on Maternal and Neonatal Health, November 2005. Final Report. July. 2006; Family Health Division, Ministry of Health and Population: Kathmandu.

- Nara Bahadur Karki. Report on Planning and Review Workshop for Strengthening Emergency Obstetric Care Services through Appreciative Inquiry. December. 2006; Family Health Division, Ministry of Health and Population: Kathmandu.

- Making pregnancy safer: the critical role of the skilled attendant. Joint statement by WHO, ICM and FIGO. 2004

- National Planning Commission. Nepal Millennium Development Goals Progress Report 2005. 2005; HM Government of Nepal: Kathmandu.

- Department of Health Services. Annual Report 2005–2006. Ministry of Health and Population, Kathmandu, 2007.

- Department of Health Services. National In-Service Training Strategy for Skilled Birth Attendants (draft). Government of Nepal, Kathmandu, 2007.

- National Health Training Centre. Maternal and Newborn Care Learning Resource package for Skilled Birth Attendants. 2007; Government of Nepal: Kathmandu.

- M Carlough, M McCall. Skilled birth attendance: what does it mean and how can it be measured? A skills assessment of maternal and child health workers in Nepal. International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics. 89: 2005; 200–208.

- G Rana, R Rajopadhaya, B Bajracharya. Comparison of midwifery-led and consultant-led maternity care for low risk deliveries in Nepal. Health Policy and Planning. 18(3): 2003; 330–337.

- AS Furber. Referral to hospital in Nepal: four years’ experiences in one rural district. Tropical Doctor. 32(April): 2002; 75–78.

- G Whiteside, H Subedi, D Thomas. Scoping study for the SSMP equity and access programme. 2005; Options UK: London.

- M Koblinsky. Reducing Maternal Mortality. 2003; World Bank: Washington DC.

- Nepal Safer Motherhood Project/Institute of Medicine, Nepal. Will a social justice approach to safe motherhood also meet the public health objective of maximising lives saved?. 2004(Unpublished)

- T Ensor. Cost sharing system for alleviating financial barriers to delivery care: review of the proposed scheme. 2005; Support to the Safe Motherhood Programme: Kathmandu.

- V Rao. Update and assessment of government–private collaborations in the health sector in Andhra Pradesh, Hyderabad. Prepared for IHSD/Harvard School of Public Health/DFID under medium-term health strategy and expenditure framework. 2003

- B Meesen, W Van Damme, CK Tashobya. Poverty and user fees for public health care in low-income countries: lessons from Uganda and Cambodia. Lancet. 368: 2006; 2253–2257.

- J Borghi, T Ensor, A Somanathan. Mobilising financial resources for maternal health. Lancet. 368: 2006; 1457–1465.

- T Wardlaw, D Maine. Process indicators for maternal mortality programmes. M Berer, TKS Ravindran. Safe Motherhood Initiatives: Critical Issues. 2000; Reproductive Health Matters: London, 24–30.

- J McCarthy, D Maine. A framework for analysing the determinants of maternal mortality. Studies in Family Planning. 23(1): 1992; 23–33.

- Department of Health Services. Annual Reports: 2003–2004, 2004–05, 2005–2006. Ministry of Health and Population, Kathmandu. 2005, 2006, 2007.

- Department for International Development. Reducing maternal deaths: evidence and action. First progress report. 2005; DFID: London.

- K Kollman. Outside lobbying, public opinion and interest group strategies. 1998; Princeton University Press: Princeton.

- Health Sector Reform Support Programme. RTI International/Policy Planning and International Cooperation Division, Ministry of Health and Population. Nepal’s experience on advocacy and lobbying for increasing budget in the health sector. Kathmandu: RTI International, 2007. (Unpublished)