Abstract

Health systems in countries emerging from conflict are often characterised by damaged infrastructure, limited human resources, weak stewardship and a proliferation of non-governmental organisations. This can result in the disrupted and fragmented delivery of health services. One increasingly popular response to improve health service delivery in post-conflict countries is for the country government and international donors to jointly contract non-governmental organisations to provide a Basic Package of Health Services for all the country’s population. This approach is being applied in Afghanistan and Southern Sudan and is planned for the Democratic Republic of Congo. The approach is novel because it is intended as the only primary care service delivery mechanism throughout the country, with the available financial health resources primarily allocated to it. Although the aim is to scale up health services rapidly, including sexual and reproductive health services, there are a number of implications for such sub-sectors. This paper describes the Basic Package of Health Services contracting approach and discusses some of the potential challenges this approach may have for sexual and reproductive health services, particularly the challenges of availability and quality of services, and advocacy for these services.

Résumé

Dans les pays émergeant d’un conflit, les systèmes de santé sont souvent caractérisés par des infrastructures endommagées, des ressources humaines limitées, la faiblesse de la direction et une prolifération d’organisations non gouvernementales, ce qui peut aboutir à une désorganisation et une fragmentation des services de santé. Pour améliorer la prestation des services de santé dans ces pays, il est de plus en plus fréquent que le gouvernement national et les donateurs internationaux passent conjointement un contrat avec des organisations non gouvernementales chargées d’assurer un ensemble de services sanitaires de base pour toute la population du pays. Cette approche est appliquée en Afghanistan et au Sud Soudan, et elle est prévue pour la République démocratique du Congo. Elle est novatrice en cela qu’elle est le seul mécanisme de prestation des soins de santé primaires dans l’ensemble du pays et que les ressources financières de santé sont principalement allouées par son truchement. Même si le but est d’élargir rapidement les services de santé, y compris de santé génésique, il existe un certain nombre de conséquences pour ces sous-secteurs. Cet article décrit l’approche contractuelle de l’ensemble de services sanitaires de base et aborde certains de ses enjeux potentiels pour les services de santé génésique, en particulier du point de vue de la disponibilité et la qualité des services, et du plaidoyer pour ces services.

Resumen

Los sistemas de salud en países emergentes de conflicto suelen caracterizarse por una infraestructura deficiente, recursos humanos limitados, liderazgo débil y una proliferación de organizaciones no gubernamentales. Esto puede propiciar la interrupción y fragmentación de la prestación de servicios de salud. Una respuesta cada vez más popular para mejorar dicha prestación en países post-conflicto es que el gobierno del país y los donantes internacionales contraten conjuntamente organizaciones no gubernamentales para proporcionar un Paquete Básico de Servicios de Salud para toda la población. Esta estrategia se está aplicando en Afganistán y Sudán Meridional, y está planeada para la República Democrática del Congo. Es una estrategia novedosa porque fue ideada como el único mecanismo de prestación de servicios en el primer nivel de atención, en todo el país, con los recursos financieros de salud disponibles principalmente asignados a ella. Aunque el objetivo es la rápida ampliación de los servicios de salud, incluidos los de salud sexual y reproductiva, existen numerosas implicaciones para estos subsectores. En este artículo se describe la estrategia de contratación del Paquete Básico de Servicios de Salud, y se analizan algunos de los retos posibles en cuanto a los servicios de salud sexual y reproductiva, particularmente los retos de disponibilidad y calidad de los servicios, así como su promoción y defensa.

The importance of sexual and reproductive health services in contributing to better health indicators and poverty reduction is well established.Citation1–3 Conflict can increase vulnerability to poor sexual and reproductive health and the need for sexual and reproductive health services is particularly acute in countries emerging from conflict.Citation4–6 The capacity to provide health services, including for sexual and reproductive health, is often extremely limited in countries that have emerged from conflict. The health service infrastructure can be severely damaged, the availability and training of health staff reduced, the drug supply affected, management systems are often weak and the capacity at the Ministry of Health may be limited. There is also often a proliferation of non-governmental organisations (NGOs) and vertical programmes, which may be poorly coordinated.Citation7 This often results in fragmented health services with limited effectiveness, efficiency and equity.

One increasingly popular response to these problems in post-conflict countries is for the country’s government and donors to jointly contract NGOs to provide a Basic Package of Health Services (BPHS) as the principle means of long-term health service delivery for the country’s whole population. The aim is to rapidly scale-up health services with proven, affordable health interventions and replace the fragmented, uncoordinated, vertically-dominant services characteristic in many post-conflict settings.

The Basic Package of Health Services contracting approach builds upon previous initiatives in Cambodia and a number of other low-income countries, which were usually only provided in specific districts or for individual health interventions, such as nutrition or tuberculosis.Citation8–11 However, the contracting approach in Afghanistan and Southern Sudan, and planned for the Democratic Republic of Congo, is novel because it is intended as the only primary care service delivery mechanism throughout the country, with the available financial health resources allocated primarily to it. This has implications for health sub-sectors and the role of vertical programmes. This paper describes the Basic Package of Health Services contracting approach and discusses some of the key challenges it may have for sexual and reproductive health services, focusing particularly on the issues of availability and quality of services and advocacy activities.

The Basic Package of Health Services

The Basic Package of Health Services contracting approach has been driven largely by the World Bank. Different packages are currently being implemented in Afghanistan and Southern Sudan, and planned for the Democratic Republic of Congo. Key donors include the World Bank, European Commission and individual European nations, the Asia Development Bank and the US Agency for International Development (USAID), amongst others. The funding is either coordinated by allocating donors to provinces, as in Afghanistan, or centrally pooled, as in Southern Sudan. The country’s government is expected to contribute financially to the Basic Package of Health Services over the longer term.

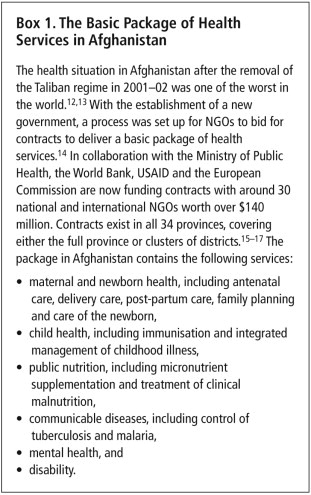

The country’s government, with assistance from donors, the UN and NGOs decides the content of the package based upon the country’s health needs and the cost-effectiveness of interventions in relation to the resources available for the package. The service delivery levels generally include health posts, health centres and district hospitals. The content of the package is primarily based upon internationally recognised cost-effective interventions and endorsed by the country’s government. These interventions commonly include maternal and newborn health, reproductive health, child health and immunisation, communicable diseases and nutrition. Additional services can also be included, depending on the country’s particular health needs. In Afghanistan (Box 1), for example, services to address disability have been included in order to support the high numbers of persons injured by land mines and other weapons. NGOs are then contracted by the country government and donors to deliver all the services included in the package.

A bidding process is established for national and international NGOs to compete for a service contract to provide the package in specific geographical areas (e.g. a province) selected by the government and the donors. The government and donors then manage and evaluate the performance of the NGOs. After a number of years, the bidding process is repeated for the next round of contracts. The government has a stewardship role which involves reviewing contract bids, evaluating NGO performance and establishing strategies, standards and regulations. The Basic Package of Health Services contracting approach is viewed by some as an intermediate measure to last for a few years until the country’s government can resume providing services directly, while others argue that this could become a more permanent feature of organising health service delivery.Citation17

The arguments in support of the Basic Package of Health Services contracting approach are based on the concepts of effectiveness, efficiency and equity. It is argued that the prioritisation of essential health services is the most effective way of reducing key health outcomes of death and disability,Citation9 and that the strengthening of a co-ordinated, horizontal, nationwide service delivery system increases effectiveness, efficiency and equity of service delivery.Citation9,18 Effectiveness and equity are improved by contracting NGOs to provide and rapidly scale up the coverage of basic health services, rather than relying on the limited capacity of government services.Citation17 NGOs are often already providing most of the health services and so have the experience and expertise to increase coverage. The greater flexibility and innovative capacity of NGOs also makes them more able to respond rapidly and effectively than weak, bureaucratic government systems.Citation19 The focus on measurable results encourages accountability, improved quality and performance of individual NGOs and the effectiveness and efficiency of the health sector as a whole. Efficiency is further improved through the competition of the bidding process and because it follows a cost-effectiveness approach.Citation9 Although there is limited evidence of the impact of the Basic Package of Health Services approach in Afghanistan and Southern Sudan, due its recent introduction, initial research from Afghanistan suggests it has rapidly expanded primary health care services.Citation15Citation17

Concerns over such packages include unease with the strong focus on cost-effectiveness. The emphasis on interventions to reduce death and disability may risk ignoring interventions with important, but less tangible, benefits to overall health and well-being.Citation20 Other concerns tend to focus on the contracting process. These include whether competition genuinely exists in areas where there may be no alternative providers.Citation17 In the longer term, there is concern about whether the contracting of NGOs strengthens the overall health system, and the capacity, function and legitimacy of the government.Citation15 The contracting approach also has implications for sub-sectors such as sexual and reproductive health, and specialist service providers in these sectors, who may be marginalised.

Implications for availability of sexual and reproductive health service delivery

The Basic Package of Health Services approach potentially offers a rapid expansion in the availability of sexual and reproductive health services compared to existing services and also compared to pre-conflict services. Table 1 summarises the extent to which sexual and reproductive health services have been included in the packages for AfghanistanCitation14 and Southern Sudan,Citation21 based upon international standards for sexual and reproductive health services for conflict-affected populations.Citation22–25 It illustrates that a large number of key services are included in both countries, which could significantly increase access to sexual and reproductive health care in both countries. The main omission is services addressing sexual and gender-based violence. This is despite evidence of high rates of such violence during and after such conflict, as in Southern Sudan.Citation26Citation27 This omission is compounded by the fact that mental health services are also not included in Southern Sudan. Specialist information and services for young people are also not mentioned. This is despite strong evidence globally of the need for and effectiveness of youth-friendly information and services on sexual and reproductive health.Citation28–30

In Afghanistan, it appears that the provision of family planning at health centres has increased as a result of the introduction of the Basic Package of Health Services but that delivery care remains limited.Citation31Citation32 However, there is generally very limited evidence of the overall impact of the contracting approach on reproductive health, particularly in Southern Sudan, where it has only very recently been introduced.

Moreover, there are a number of factors that could undermine the availability of sexual and reproductive health services. Firstly, the need to show efficiency and cost-effectiveness and the strong focus on reducing death and disability may lead to restrictions on which sexual and reproductive health services are prioritised or included. Clearly many reproductive health interventions directly reduce mortality, disability and morbidity.Citation2 However, the less tangible benefits for overall health and well-being to individuals, their families and their communities provided by certain health interventions may be overlooked in certain cost-effectiveness approaches.Citation20 For example, specialist services and information activities for young people are not included in either of the Basic Packages of Health Services in Table 1, despite strong evidence of the value of and need for youth-friendly services and activities.Citation28–30 Similarly, cost-effectiveness approaches may not recognise the importance of addressing gender-based violence, which is also absent from the packages for Afghanistan and Southern Sudan (Table 1). The contracting approach should therefore be flexible enough to allow NGOs to budget for and provide these services.

Secondly, the bidding process and use of competition to increase efficiency deliberately puts pressure to contain costs. This could have an impact upon the availability of services. In Afghanistan, NGOs responded to the competitive process with widely varying estimates of the cost of delivering the Basic Package of Health Services. Some may have underestimated costs in an effort to win contracts.Citation15Citation17 This could result in some services being reduced, such as for sexual and reproductive health, which historically have been less prioritised by the humanitarian community.Citation33Citation34 Contracts will need to be closely monitored by the government and donors to correct for under-estimated costs or reduced services. Intensive monitoring is difficult in post-conflict countries such as Afghanistan and Southern Sudan, however, which are characterised by instability and poor communications.

Thirdly, the availability of sexual and reproductive health services may be adversely affected by the influence of conservative political, religious and cultural forces, which are threatening to undermine provision of key sexual and reproductive health services globally,Citation1 including for family planning.Citation35–37 Similarly, the international failure to adequately address unsafe abortion is particularly acute in countries emerging from conflict.Citation35,38,39 At the NGO level, Basic Package of Health Services contracts may be awarded to faith-based organisations that may not want to provide family planning or adequately address other key components of sexual and reproductive health, such as unsafe abortion. The Southern Sudan package recognises this and recommends that if a faith-based organisation contracted to provide basic services is not willing to provide services such as family planning, it should sub-contract these services to another organisation.Citation21 However, the extent to which faith-based organisations actually will sub-contract to other NGOs should be closely monitored.

At the community level, the controversial nature of some reproductive health services may make them vulnerable to local pressures which a decentralised system, such as the Basic Package of Health Services, may be less able to respond to.Citation40 This is all despite evidence of high demand and unmet need for sexual and reproductive health services amongst people affected by conflict.Citation29,41,42 Governments and donors in these settings need to monitor service provision closely, and support NGOs in the provision of sexual and reproductive health services. In Afghanistan, due to the absence of a functioning routine health information system, a balanced scorecard system is being used to evaluate performance of health services, involving household and health facility surveys.Citation31Citation32 However, indicators for sexual and reproductive health are limited to family planning availability and delivery care only.

Quality of care

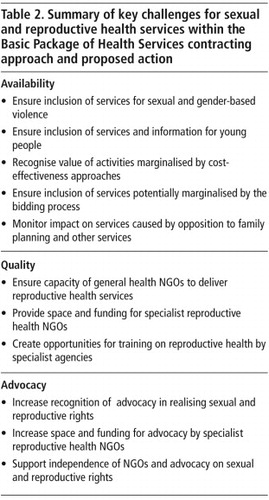

The Basic Package of Health Services contracting approach also poses challenges for ensuring the quality of sexual and reproductive health services. Evidence suggests that general health NGOs who may be contracted to provide the Basic Package of Health Services may not have the experience, knowledge or commitment to deliver sexual and reproductive health services according to internationally agreed standards.Citation33Citation34 Specialist sexual and reproductive health NGOs have technical expertise, but also the experience and knowledge to address the sensitive and controversial nature of reproductive health to gain community trust and support. However, there may be very limited space and funding available for NGOs working in specific health sub-sectors, such as reproductive health, to provide services, give training and technical assistance, and monitor and evaluate the quality of services. The potential absence or reduced space for specialist sexual and reproductive health NGOs is currently an issue in Afghanistan (Table 2) and potentially could be in Southern Sudan but it is too early to know yet given the recent introduction of the Basic Package of Health Services there.

Advocacy activities for sexual and reproductive health services

The controversial nature of sexual and reproductive health means proclaimed rights relating to sexual and reproductive choices, including access to services, are often contested and denied at local, national and international levels.Citation43Citation44 This can be particularly so in conflict and post-conflict environments.Citation45 As a result, access to reproductive health services is reduced and reproductive morbidity under-reported because of fear and stigma.Citation2 Realising reproductive rights and improving reproductive health requires moving beyond a focus only on the technical quality of clinic-based services to incorporating efforts to address the gender and power dimensions of reproductive and sexual decision-making.Citation46 There is a strong need for organisations to advocate for sexual and reproductive health rights at community, national and international levels as part of the post-conflict reconstruction process (Table 2).Citation47 The potential absence of dedicated sexual and reproductive health NGOs as a result of the Basic Package of Health Services contracting approach would remove an important resource for influencing community attitudes, government and donor policies and programmes.

Concerns have also been noted that contracting will result in NGOs not feeling able to criticise governments or donors and play an effective advocacy role. Recommendations are made by proponents of the Basic Package of Health Services contracting approach that NGOs should be able to decline to participate in contracts if they believe it would compromise their other roles.Citation48 However, there may be limited space and few alternative funding sources for NGOs to operate outside of the Basic Package of Health Services approach. International donors recognise the importance of an independent civil society.Citation49 This should be reflected in supporting advocacy initiatives on reproductive rights in countries following a BPHS contracting approach.

Conclusion

The Basic Package of Health Services contracting approach could provide an important means for rapidly scaling up effective, efficient and equitable sexual and reproductive health services in countries emerging from conflict. However, there are a number of challenges relating to the availability and quality of services, and advocacy activities on sexual and reproductive health.

Governments and donors involved in the Basic Package of Health Services could adopt a flexible approach to allow NGOs to provide comprehensive sexual and reproductive health services and activities, while still following a Basic Package of Health Services contracting approach. The government and donors also need to monitor and evaluate NGO performance to ensure that the full range of sexual and reproductive health services included in the Basic Package are being provided and to the required quality. Existing monitoring and evaluation mechanisms, such as the balanced scorecard system used in Afghanistan, could be expanded to include a more comprehensive range of sexual and reproductive health indicators appropriate to the country.

Specialist sexual and reproductive health NGOs could help to train providers of the Basic Package of Health Services. These NGOs can also provide support to local organisations advocating on issues related to reproductive health and rights. Governments and donors have a key role in providing space and support to such organisations.

If the potential opportunities provided by the Basic Package of Health Services contracting approach for the expanded provision of sexual and reproductive health in post-conflict settings are to be fully realised, government, donors, and NGOs will need to adopt a flexible and broad-based approach to help advance comprehensive reproductive health.

References

- A Glasier, A Gulmezoglu, G Schmid. Sexual and reproductive health: a matter of life and death. Lancet. 368(9547): 2006; 1595–1607.

- L Singh, J Darroch, M Vlassoff. Adding It Up. The Benefits of Investing in Reproductive Health Care. 2003; Alan Guttmacher Institute/UNFPA: Washington DC/New York.

- United Nations Development Programme UN Millennium Project. Investing in development: a practical plan to achieve the Millennium Development Goals. 2005; UNDP: New York.

- J Busza, L Lush. Planning reproductive health in conflict: a conceptual framework. Social Science and Medicine. 49(2): 1999; 155–171.

- T McGinn, S Purdin. Reproductive health and conflict: looking back and moving ahead [Editorial]. Disasters. 28(3): 2004; 235–238.

- K van Egmond, A Naeem, H Verstraelen. Reproductive health in Afghanistan: results of a knowledge, attitudes and practices survey among Afghan women in Kabul. Disasters. 28(3): 2004; 269–282.

- E Pavignani, A Colombo. Analysing Disrupted Health Sectors: A Toolkit. Module 1: The Crisis Environment. 2005; World Health Organization: Geneva.

- J Doherty, R Govender. The cost-effectiveness of primary care services in developing countries: a review of the international literature. 2004; Disease Control Priorities Project: Johannesburg.

- B Loevinsohn, A Harding. Buying results? Contracting for health service delivery in developing countries. Lancet. 366(9486): 2005; 676–681.

- A Mills, J Broomberg. Experiences of contracting: an overview of the literature. 1998; World Health Organization: Geneva.

- World Bank. Investing in Health: World Development Report. 1993; World Bank: Washington DC.

- L Bartlett, S Mawji, S Whitehead. Where giving birth is a forecast of death: maternal mortality in four districts of Afghanistan, 1999–2002. Lancet. 365(9462): 2005; 864–870.

- W Newbrander, P Ickx, G Leitch. Addressing the immediate and long-term health needs in Afghanistan. Harvard Health Policy Review. 4(1): 2003. At: <www.hhpr.org/currentissue/spring2003/index.php. >.

- Ministry of Public Health. A Basic Package of Health Services for Afghanistan. 2003; Ministry of Public Health, Transitional Islamic Government of Afghanistan: Kabul.

- N Palmer, L Strong, A Wali. Contracting out health services in fragile states. BMJ. 332(7543): 2006; 718–721.

- B Sabri, S Siddiqi, A Ahmed. Towards sustainable delivery of health services in Afghanistan: options for the future. Bulletin of World Health Organization. 85(9): 2007; 712–718.

- L Strong, A Wali, E Sondorp. Health policy in Afghanistan: two years of rapid change. 2005; London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine: London.

- W Newbrander, R Yoder, AB Debevoise. Rebuilding health systems in post-conflict countries: estimating the costs of basic services. International Journal of Health Planning and Management. 22(4): 2007; 319–336.

- G Cometto. Contracting out: a different viewpoint from South Sudan. BMJ. 332: 2006. (Rapid response).

- G Mooney, V Wiseman. Burden of disease and priority setting. Health Economics. 9(5): 2000; 369–372.

- Ministry of Health. Basic Package of Health Services for Southern Sudan (2nd draft). 2007; Ministry of Health, Government of Southern Sudan: Juba.

- Inter-Agency Standing Committee. Guidelines for Gender-based Violence Interventions in Humanitarian Settings. 2005; Inter Agency Standing Committee: Geneva.

- International Planned Parenthood Foundation, IPPF Medical and Service Delivery Guidelines. 3rd ed., 2004; IPPF: London.

- Sphere Project. Humanitarian Charter and Minimum Standards in Disaster Response. 2004; Sphere Project: Geneva.

- WHO/UNFPA/UNHCR. Reproductive Health in Refugee Situations. 1999; WHO/UNFPA/UNHCR: Geneva.

- L Elia. Fighting gender-based violence in South Sudan. Forced Migration Review. 27: 2007; 39.

- M Hynes, K Robertson, J Ward. A determination of the prevalence of gender-based violence among conflict-affected populations in East Timor. Disasters. 28(3): 2004; 294–321.

- LH Bearinger, R Sieving, J Ferguson. Global perspectives on the sexual and reproductive health of adolescents: patterns, prevention, and potential. Lancet. 369(9568): 2007; 1220–1231.

- M Bosmans, M Cikuru, P Claeys. Where have all the condoms gone in adolescent programmes in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Reproductive Health Matters. 14(28): 2006; 80–88.

- PK Kayembe, A Fatuma, M Mapatano. Prevalence and determinants of the use of modern contraceptive methods in Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of Congo. Contraception. 74(5): 2006; 400–406.

- Ministry of Public Health, Johns Hopkins University Bloomberg School of Public Health, Indian Institute of Health Management Research. Afghanistan Health Sector Balanced Scorecard: National and Provincial Results (Round Three). Kabul, 2007.

- DH Peters, A Noor, L Singh. A balanced scorecard for health services in Afghanistan. Bulletin of World Health Organization. 85(2): 2007; 146–151.

- Inter-Agency Working Group. Inter-Agency Global Evaluation of Reproductive Health Services for Refugees and Internally Displaced Persons. 2004; IAWG: Geneva.

- L Kealy. Women refugees lack access to reproductive health services. Population Today. 27(1): 1999; 1–2.

- J Cleland, S Bernstein, A Ezeh. Family planning: the unfinished agenda. Lancet. 368(9549): 2006; 1810–1827.

- P Senanayake, S Hamm. Sexual and reproductive health funding: donors and restrictions. Lancet. 363(9402): 2004; 70.

- UNFPA. Financial resource flows for population and AIDS activities. 2006; UNFPA: New York.

- S Belton, C Maung. Fertility and abortion: Burmese women’s health on the Thai-Burma border. Forced Migration Review. 19: 2005; 36–37.

- U Sandbœk. The global gag on reproductive health rights. Forced Migration Review. 19: 2004; 20.

- R Lakshminarayanan. Decentralisation and its implications for reproductive health: the Philippines experience. Reproductive Health Matters. 11(21): 2003; 96–107.

- Uganda Bureau of Statistics, Uganda Demographic and Health Survey 2006: Preliminary Report. Kampala, 2006.

- Women’s Commission for Refugee Women and Children, UNFPA. We Want Birth Control: Reproductive Health Findings in Northern Uganda. 2007; Women’s Commission/UNFPA: New York/Washington DC.

- R Cook, B Dickens, M Fathalla. Reproductive Health and Human Rights: Integrating Medicine, Ethics and Law. 2003; Clarendon Press: Oxford.

- R Petchesky, K Judd, with IRRAG. Negotiating Reproductive Rights: Women’s Perspectives Across Countries and Cultures. 1998; Zed Books: London.

- Y Tambiah. Sexuality and women’s rights in armed conflict in Sri Lanka. Reproductive Health Matters. 12(23): 2004; 78–87.

- JL Jacobson. Transforming family planning programmes: towards a framework for advancing the reproductive rights agenda. Reproductive Health Matters. 8(15): 2000; 21–32.

- B Klugman. Organising and financing for sexual and reproductive health and rights: the perspective of an NGO activist turned donor. Reproductive Health Matters. 12(24): 2004; 14–24.

- B Loevinsohn, A Harding. Contracting for the delivery of community health services: a review of global experience. 2003; World Bank: Washington DC.

- Department for International Development. Civil Society and Development: How DFID works in partnership with civil society to deliver the Millennium Development Goals. 2006; DFID: London.