Abstract

The Eastern region of the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) is currently undergoing a brutal war. Armed groups from the DRC and neighbouring countries are committing atrocities and systematically using sexual violence as a weapon of war to humiliate, intimidate and dominate women, girls, their men and communities. Armed combatants take advantage with impunity, knowing they will not be held to account or pursued by police or judicial authorities. A particularly inhumane public health problem has emerged: traumatic gynaecological fistula and genital injury from brutal sexual violence and gang-rape, along with enormous psychosocial and emotional burdens. Many of the women who survive find themselves pregnant or infected with STIs/HIV with no access to treatment. This report was compiled at the Doctors on Call for Service/Heal Africa Hospital in Goma, Eastern Congo, from the cases of 4,715 women and girls who suffered sexual violence between April 2003 and June 2006, of whom 702 had genital fistula. It presents the personal experiences of seven survivors whose injuries were severe and long-term, with life-changing effects. The paper recommends a coordinated effort amongst key stakeholders to secure peace and stability, an increase in humanitarian assistance and the rebuilding of the infrastructure, human and physical resources, and medical, educational and judicial systems.

Résumé

La région orientale de la République démocratique du Congo (RDC) connaît actuellement une guerre particulièrement brutale. Des groupes armés de la RDC et des pays voisins commettent des atrocités et utilisent systématiquement la violence sexuelle comme arme de guerre pour humilier, intimider et dominer les femmes, les jeunes filles, leurs partenaires masculins et les communautés. Les combattants armés jouissent de l’impunité, sachant qu’ils ne devront pas répondre de leurs actes et ne seront pas poursuivis par la police ou les autorités judiciaires. Un problème de santé publique particulièrement atroce est apparu : les fistules gynécologiques traumatiques et les lésions génitales causées par les violences sexuelles et les viols collectifs, avec des conséquences psychosociales et psychologiques tragiques. Beaucoup de victimes se retrouvent enceintes ou infectées par des IST ou le VIH, sans accès au traitement. Ce rapport a été préparé à l’hôpital Heal Africa/Doctors on Call for Service à Goma, en RDC orientale, à partir de 4715 cas de femmes et de jeunes filles ayant subi des violences sexuelles entre avril 2003 et juin 2006, dont 702 présentaient une fistule génitale. Il décrit les expériences personnelles de sept victimes dont les blessures étaient si graves qu’elles ont changé leur vie. L’article recommande aux principales parties prenantes de coordonner leurs efforts pour garantir la paix et la stabilité, accroître l’assistance humanitaire et reconstruire l’infrastructure, les ressources humaines et matérielles ainsi que les systèmes médicaux, éducatifs et judiciaires.

Resumen

La región oriental de la República Democrática del Congo (RDC) actualmente se encuentra asolada por una guerra brutal. Grupos armados de RDC y países vecinos están cometiendo atrocidades y utilizando la violencia sexual sistemáticamente como un arma de guerra para humillar, intimidar y dominar a las mujeres, niñas, sus hombres y comunidades. Los combatientes armados sacan provecho con impunidad, sabiendo que no se les hará responsable ni serán perseguidos por la policía o autoridades judiciales. Ha surgido un problema de salud particularmente inhumano: fístula ginecológica traumática y lesión genital a consecuencia de actos brutales de violencia sexual y violación en grupo, así como enormes secuelas psicosociales y psicológicas. Muchas de las mujeres que sobreviven se encuentran embarazadas o infectadas con ITS/VIH, sin acceso a tratamiento. Este informe fue compilado en el Hospital Doctors on Call for Service/Heal Africa Hospital, en Goma, Congo oriental, de los casos de 4,715 mujeres y niñas que sufrieron violencia sexual entre abril de 2003 y junio de 2006, de las cuales 702 tenían fístula genital. Se exponen las experiencias personales de siete sobrevivientes cuyas lesiones eran graves y de largo plazo, con efectos que les cambiaron la vida. Se recomienda un esfuerzo coordinado entre las partes interesadas clave a fin de lograr paz y estabilidad, un aumento en ayuda humanitaria y reconstrucción de la infraestructura, recursos humanos y físicos, y sistemas médicos, educativos y judiciales.

The mineral riches of the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) and its status as involuntary domicile to combatants from neighbouring countries have played a critical role in the conflict that has ravaged the country for many years. Political tension, civil war and interethnic conflict was exacerbated in the aftermath of the Rwandan genocide in 1994, followed by the presence of ex-Rwandan Forces and Interhamwe militias in Eastern DRC. The conflict escalated into a second war that has drawn no less than seven foreign country armies onto Congolese soil as well as packs of Mai-Mai (traditional Congolese resistance fighters) and rebel groups. The armed groups lack a central command structure and are responsible for atrocities, looting and destruction. More than four million lives have been lost.Citation1–3

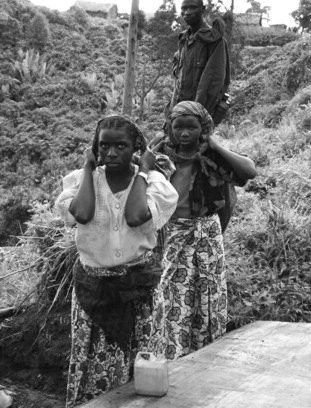

Socio-economic structures in the war-ravaged region have collapsed. Women and girls who cultivate the fields, make charcoal in the forest or trade goods in the market so as to earn a livelihood for themselves and their families are easy prey.Citation4 Out of the chaos of conflict, a particularly inhumane public health problem has emerged: gynaecologic fistula and traumatic genital injury from especially brutal sexual violence.

The brutality unleashed against women and girls in the Eastern DRC has been extensively documented elsewhere, notably by Human Rights Watch, as “the war within the war”.Citation1 As military activities have increased, sexual violence has increased in tandem and has itself come to be used as a weapon of war. The perpetrators are often motivated by a desire for power and domination, and they use sexual violence to humiliate, intimidate, control and violate the physical and mental integrity of the women and girls, the men and the whole community. The women and girls are sometimes gang-raped and violated in a systematic fashion, often in full, deliberate and enforced view of husbands and family members. Other civilians are killed, and their property pillaged and destroyed. The perpetrators are mostly military and other armed combatants. But there are also incidents involving the police, civilians and others in positions of authority, as well as opportunistic criminals.

The sexual violence is widespread and pervasive. Gang-rape is often exacerbated by other forms of extraordinary sexual savagery, including the forcing of crude objects such as tree branches and bottles into the vagina. Sometimes the women are tortured, their genitalia mutilated with knives or bayonets or burned with naked flame. Or they are shot through a gun barrel thrust into the vagina.

One dreaded outcome of the trauma from sexual violence is genital fistula, defined as an abnormal communication between the vagina and the urinary tract (usually the bladder), or between the vagina and the alimentary tract (usually the rectum) or both.Citation5 The fistula leads to uncontrollable leakage of urine or faeces or both through the vagina.

Worldwide, the most common causes of genital fistula are obstetric, principally from obstructed labour, especially in rural regions of the developing world.Citation6Citation7 The literature generally does not highlight rape as an important cause of traumatic gynaecologic fistulaCitation8Citation9 and, indeed, some researchers have disputed an association of any significant public health magnitude. Some reports of traumatic fistula are documented from recently war-torn African nations such as Sierra Leone and Liberia.Citation4 However, moderate genital tears are generally the only physical consequence of rape mentioned in western countries. This paper goes towards demonstrating personal experiences of women and girls who have survived sexual violence but ended up with traumatic gynaecologic fistula and/or other severe genital injuries.

The investigators took precautions to protect the real name and identity of survivors. Where possible, they visited peripheral sites and/or sought eyewitness testimony to corroborate survivors’ accounts. The case series was compiled in April 2003–June 2006 from illustrative cases managed at the Doctors on Call for Service/Heal Africa (DOCS/HA) Hospital in Eastern DRC. 4,715 of the women reported having suffered sexual violence; 4,009 received medical treatment; 702 had fistula, 63.4% being traumatic and 36.6% being obstetric.

Testimonies of survivors

• Bupole’s testimony

Bupole, 19, was born into a family of four boys. She was the youngest and the only girl in the family.

I have no father or mother. We lived on what we cultivated in our fields and the family lived in harmony. None of the children could read or write at all, because the nearest school was more than a 12 hour walk away through dense forest.

Because of the war and insecurity, we visited our house only during the day, and only for storage, never for rest. We spent our nights out in the forest not far from our fields. In the mornings we would gather food; toward noon we would return to the village for two or three hours, just enough time to prepare a meal that we ate quickly for fear of being ambushed and captured by armed militia scavenging for women and food. By four in the afternoon, everyone routinely trekked back to the forest to seek refuge for the night.

But the day befell us that we had always feared. The men we so dreaded and against whom we had taken all those precautions for all those months suddenly appeared, earlier than expected. They surrounded the entire village and began firing in every direction, killing anyone who attempted to flee. A bullet hit my father in the neck and he fell, dying. Another bullet hit my mother in the thigh as we tried to escape. I stopped in mid-flight, I could not abandon her. Five men caught up with me as I tried to help her. They tied me up and stuffed a gag into my mouth. Then they raped me again and again.

I was unconscious for hours, and they must have finally left. Much later, a different group of armed men came to our rescue. However, it was too late for my mother who slowly bled to death. This second group of men brought my mother’s body to a neighbouring village, along with me and five other women who had been brutalised like me. On that one day, my village buried 25 of its members.

My mind was in anguish, my entire body was in terrible pain and I was bleeding through my private parts. Over the next two days, I realised I could not hold my urine, even though I had no sensation of needing to urinate. Everything flowed out of me as soon as I drank. I was beyond depression. No one could stand to be near me because of the stench.

A long time later, I received some hope after hearing from two women who had suffered from the same ailment as I had. They had been treated for urine leakage and healed after being taken to a hospital in Goma. Their reassurance helped me so much that I decided I would also seek care. I am now awaiting my third operation.

Bupole survived the gang-rape, but with a complex vesico-vaginal fistula. She had severe adhesions of the vaginal walls, causing almost complete obliteration and absence of the vaginal cavity and requiring difficult surgery. The initial repair surgery was unsuccessful. The next surgical intervention planned is a urinary diversion.

• Byamungu’s testimony

Byamungu was 12 years old. She was the fourth in a family of seven. Medical care is not only costly, it is almost non-existent.

I have worked since I was eight. I used to bring palm oil to the market. We would walk four hours on foot with our merchandise on our back. If I had no buyer, I would leave my jerry can there because the distance was so great. But when business was good, I would buy soap and bring the remaining money to my parents.

One day when we were returning from the market with a group of women, I felt a need to open my bowels. Since the only place to go was in the forest, I told the others not to leave me. I entered to relieve myself and quickly returned to the path, fast on their heels.

But my hour of darkness had come. Suddenly a group of men appeared behind me. One of them grabbed me by the hand. I screamed, but my frightened companions were already running away; the more I screamed the faster they ran. Abandoned, I was facing eight beasts who first robbed me of the money and packets of soap, then three of them dragged me into the bush, stripped me naked and raped me repeatedly. The other five did not seem to approve of their brothers’ brutality and tried to stop them, but only half-heartedly and unsuccessfully. The pain was like having knives plunged inside my body as they raped me in turns. I do not know how to forgive these people, or how to forget.

When they were done they left me there bleeding, moaning in pain, until a group of women found me slumped on the ground. One of them carried me on her back until we reached a health centre. Her entire back was covered in my blood. Another woman from my village went to inform my parents. That night the entire village came to the health centre to see the damage: faeces and urine flowed out of the same opening in my body.

After a week at the health centre, I spent another three weeks at home before being taken to the hospital in Goma for surgery. I can now control my bladder, but not completely my bowels.

Byamungu’s gang-rape resulted not just in fistulae as “holes”, but as severe tears and complete rupture of the perineum along with vesico-vaginal and recto-vaginal fistulae. Operative surgical repair was successful and she is now healed. She is currently receiving psychological and social support from social counsellors.

• Rehema’s testimony

Rehema was 34 years old and had been married for eight years without being able to conceive. She and her husband were peasant farmers.

Because I could not conceive, my husband decided to take a second wife, and they eventually had four children. My co-wife could not stand to see me touch her children; she called me a witch, a sterile witch. My life with them became miserable and unhappy. So, I dedicated myself to prayer and hoping that I would one day conceive.

Years later, when I was over 30, I became pregnant for the first time in my life. This did nothing to change the attitude of my husband or his wife towards me. Still, it brought me an inner calm. In my village there was no chance of antenatal care. I jealously guarded my pregnancy against all of life’s ups and downs.

Then one morning around ten, while I was in the field with my husband, a group of five armed men appeared. They demanded money but we did not have any. So they declared that we were of no use and that we deserved to die. They blindfolded me, stripped and beat me severely. Then they raped me again and again, one after the other, with my hands and feet tied to stakes. Eventually, they abandoned me there, weak and in terrible pain and dragged my husband away. I felt wet; there was a large quantity of water and blood leaking from my womb, running down my legs. Terrible abdominal cramps seized me and came with increasing waves of agony the whole night without relief.

The following day my co-wife, having noted our absence, alerted the villagers. They came to search in the fields and found me there, half dead, groaning in pain. They untied me. Between my legs lay my baby, dead, covered in insects. I was in shock and totally anguished at this blasphemy against God, humanity, against life!

Back in the village, after burying my child, the other mothers suggested I remain seated in water for days at a time. In spite of this, after a week I could not control my bladder at all and was constantly leaking and smelling of urine. This was the second terrible ordeal in my life. Having overcome childlessness, I now had to live with incontinence.

One year later, a team of counsellors visited our village and then brought me here to Goma for appropriate care. I soon realised that other women suffered from the same problem. I have just undergone three operations without much improvement. I am still leaking. Now they are proposing to divert the urine into the bowels. But this is a solution that I cannot accept; it would further decrease the chances of my husband ever accepting me back. After the second operation I returned to the village to see my people, but my husband rejected me, claiming I had AIDS.

Today I am back in the hospital and happy among other women who have become my parents, my sisters and my friends to share in my new life. Together we take solace in the fact that healing comes only from God.

Rehema’s sexual assault was followed by a difficult labour and unassisted vaginal delivery and stillbirth alone in the forest. It is uncertain whether the fistula was from the difficult labour or belatedly from the preceding sexual violence, but the distinction is mostly academic. She now suffers from a complex vesico-vaginal fistula with complete loss of the posterior bladder wall and of the urethra. She will require a urinary diversion that will permit her to reintegrate into society. She needs time and counselling to help her make an informed decision.

• Augustine’s testimony

Augustine’s mother gave this report. Augustine was six years of age, the 14th and youngest child of a large family. She lived in Kindu with her parents and was in her first year of primary school.

.. During this period, the entire town was under the control of armed groups who often wore no military insignia. But we knew them by their rifles, their knives, spears, rocks or small flasks of water that they carried. Sometimes their only distinguishing feature was their extreme brutality; these men killed over trifles. It was strictly forbidden to weep over the death of a family member on pain of facing execution yourself.

One afternoon when I was preparing the evening meal, Augustine – who loved to play with other children – left the house. Just fifteen minutes later a neighbour brought us shocking news that our little girl had been kidnapped by armed men. We panicked. My husband saw to it that no one cried, not even our youngest. We did not know if we would live to see the dawn. The night stretched on forever and sleep was impossible. Toward midnight, we heard noises outside and recognised a voice that sounded like Augustine crying. No one, not even her father, dared go outside; all the child could do was cry. Finally, her father could not bear it and decided to go outside. It was our girl, lying on the ground, abandoned and exposed, naked as a frog. The pavement was covered in blood. My daughter Augustine, only six years old, had been raped by grown men. Our fear evaporated. We were all prepared to die. We carried the child to the nearest health post but there was no treatment; so we took her to the general hospital at Kindu. She could no longer control her bowels, and faeces flowed from the same opening as her urine.

We spent one year in that hospital before transfer to Goma because, after each attempted repair, the stitches would come undone.

When we arrived at DOCS, the doctor decided that the child needed to put on weight before any new surgery. The following month he operated, and my child is doing better. As for her behaviour, she’s become disobedient, temperamental and absent-minded. She is quick to anger for no reason. From time to time, during the night, she cries and has nightmares. In my opinion, we have to bring an end to the war.

This child’s defilement resulted in tears and complete rupture of the perineum, along with recto-vaginal fistula and severe cachexia. After improving the child’s overall health and nutritional status, it was possible to perform surgical repair of the genital injuries. Today, Augustine is healed, at least physically.

• Agnes’s testimony

Agnes was born into a large and impoverished family. She never attended school. She is the youngest child in a family of 12 children. When she married at 20, she was already three months pregnant. This is a case summary rather than her own words.

In her native village of Ngungu, a state of permanent insecurity reigned, so women and children spent their nights sleeping in the bush in small groups of two or three. Everyone knew the rules – if one group was attacked, the others would flee and not look back, for fear an entire family could be wiped out.

But very early one morning, before they were awake, armed militia fell upon them. They ordered them to remove their clothes and hand everything over. One group began to beat and sodomise her husband; another group dragged Agnes away. One of them berated her, threatening that they would all pay for the militia’s fruitless search all night. At that moment she heard gunshots, her husband, she feared, being murdered. Then they forced her to the ground and brutally raped her until she lost consciousness.

They left her there until morning, when villagers came to search the fields. They collected her husband’s body and buried him. She could not walk, but they carried her for treatment to a health centre some distance away.

Afterwards, she remained at her mother’s side, terrified to go anywhere throughout her pregnancy. Her labour began at home and, for fear of their lives, her mother and her friends advised that she deliver at home. She tried to push the baby out for three days, but no baby came. Only then did they decide to transport her to a hospital for c-section, but the baby was already dead. After a week she saw “a kind of flesh” come out of her body and at the same moment “an uncontrollable and continuous flow of urine began”. She was also leaking faeces. Since then, she has lived in complete social isolation.

Agnes has lived with vesico-vaginal and recto-vaginal fistula resulting from obstructed labour for four years. Additionally, she has HIV infection and has not healed well despite fistula surgery and a temporary colostomy. She will likely need a urinary diversion into the rectum. Agnes is bitter and despondent about her misfortune.

• Giselle’s testimony

Giselle was 22 years old. She was born in Kalongosola, a small village in the province of Maniema. In this remote corner of the DRC the population sticks together and knows how to share its joys and sorrows. Schools are non-existent, and for this reason girls marry early. The closest medical centre is 12 hours away on foot. Like most girls here, Giselle was married at 16. Her first pregnancy resulted in a stillbirth after a premature delivery at home.

One night, we heard gunshots in the village. We were terrified. Houses were being systematically looted. No one knew what was happening to his neighbour, and it was pitch black outside. My husband decided to get me to safety. He did not realise there were a group of bandits already outside. When he opened the door, he was shot in the chest and fell down. The leader of this group forbade me from crying, or I would face the same punishment. Then he ordered me to follow him, along with around 30 of his men, most of them very young. They took me to Kampene, a Catholic mission that they had overrun and turned into their base, about 50 km away. I was sex slave to a tyrant for two years, with three other captive co-wives, one of them 15 years old. We dared not try to flee the camp, not only because his men controlled the surrounding countryside, but above all because the punishment for attempted escape was death to the escapee and their entire family.

In September of 2004, with the process of demobilisation underway, our “chief” was to be transferred to Kindu, the provincial seat. But one morning, he summoned me to his presence. I entered the room with foreboding and trembling. Apparently, one of his spies had informed him that I had received a greeting from a passerby, and I had to be made an example of. But he took an oath, with my co-wives as witnesses, saying: “You’ll soon be free. But I would hate to think of other men sleeping with you after me, because I’m jealous. I am going to seal your vagina.” Then he forced me to take a lamp and burn my own genitals, while he stood over me with his rifle cocked at my head. Despite my screams to the point of fainting, no one could help me. They all feared the “Supreme Commander”. After he left, one of the co-wives came and sprinkled a little water on me. No one dared take me for treatment, because the chief had not given any such order.

I suffered in my room for days, awaiting the chief‘s return. My wounds festered, and the stench was unbearable. After two weeks, the chief returned and granted me a medical pass to be treated in hospital. Healing was very slow, and was still incomplete after one month. The chief ordered his men to return me to my village so my own people could look after me.

For two months I stayed with my father. Hearing news of my return, my husband, whom I thought dead, came and found me and took the necessary steps to bring me to Goma for care. They took good care of me at the hospital, but needed to operate. My operation was successful and I am now waiting for Médécins sans Frontières to take me home.

Giselle’s gynaecological examination revealed a very constricted and scarred vaginal introitus and vulva. The surgery required removal of the sclerotic tissue and dilatation of the vaginal canal. The vaginal tissues, fortunately, were still supple.

• Tata Mwasi’s testimony

Tata Mwasi was 66, born in a village 240 km from Goma. The mother of 13, only three of her children survive today, some of them casualties of war, along with their father. In her region, life is grim: boys are either killed or recruited as “mules” to carry the spoils of war. Girls are often raped or taken as sexual hostages. This is a case summary rather than her own words.

There had been violence and increasing insecurity in her distant village forcing her to flee to a village 10 km from Goma city. Relatives helped her build a one-room adobe hut. There was no door, but she had the basic essentials.

One morning, four young men, as poorly dressed as she was, approached her hut. Two of them forced their way inside while the others guarded the entrance. One of those who had entered said, “So she’s old, but she’s still a woman.” They flung her to the ground and raped her in turns. One looked the same age as her son and, when he finished, asked her if she was also satisfied. Her humiliation and bitterness were indescribable.

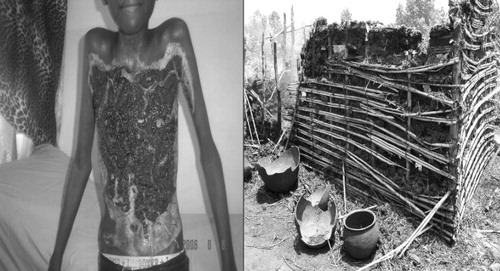

But worse was to come. As they left, the two who stood guard outside set fire to the straw roofing of her hut. It burnt like paper and the clothes that she was wearing caught fire, burning into her flesh before she was rescued by passers-by who carried her to a health centre. She had severe burns of her trunk, thighs and groin. She was transferred to DOCS/HA for further treatment in a ward with other victims of sexual violence.

Tata Mwasi’s encounter with opportunistic civilian rapists culminated in third degree, infected burns to over 27% of her body. She eventually responded well to burns management and treatment of the infection.

Discussion

These case studies indicate that fistula and traumatic gynaecological and other injury from sexual violence are common and pervasive in the conflict setting of the Eastern DRC. The physical trauma is accompanied by enormous psychosocial and emotional burdens.

The true incidence of sexual violence is unknown. It is likely that occurrences are grossly under-reported, especially in non-refugee, non-internally displaced settings, and that the true incidence is difficult to calculate. Those women and family members who are not killed outright may fail to report because of stigma and fear of retaliation.Citation1,3,10 Additionally, clinic staff, health management information systems and official statistics may not capture the data either, because of inappropriate interview, documentation and reporting techniques, which are often not adequately sensitive, discreet or confidential.

The women and girls in these case studies were poor and uneducated, although isolated cases of nurses and other medical staff being taken hostage have been reported elsewhere.

The women were preyed upon by armed combatants in the fields, along the roads or in their homesteads. Other women had sought to flee conflict by living in temporary shelters in the forests, or had sought the relative but illusory security of the peri-urban village. Women and girls could also be abducted and taken as hostages to the combatants’ bases in the forest where they were kept as sex slaves and menial

labour. The survivors of sexual violence varied in age from infants to elderly women. The weapons and means of aggravating the sexual violence varied widely in form and severity. Men were humiliated, raped mentally and emasculated by coerced incest under pain of death, or by being forced to watch their wives and daughters being gang-raped and brutalised as they stood by, impotent. Sometimes, the men were themselves physically raped or killed.The physical injuries were caused in all kinds of ways, from gang-rape to introduction of foreign objects into the genitalia, to gunshot wounds. It is significant that some cases of fistula appeared to be of obstetric origin. The perceived risk of sexual violence and death in this conflict setting posed an insurmountable barrier to seeking crucial, emergency obstetric care if a woman had obstructed labour.

For the supposedly “lucky” women who were not killed outright, the genital injuries themselves could be protean and horrific in manifestation; they often required difficult and painstaking surgery. From a clinical point of view, it is correct to use the wider definition of fistula as an “an abnormal communication” rather than just an opening, not only for girls but also for women. The injuries and tears are often much more extensive than just an opening, sometimes involving the whole of the vesico-vaginal or recto-vaginal wall, or even the whole perineum, apart from other pelvic and abdominal structures. Often, there is additional damage to sexual and coital function, and reproductive capacity is also compromised. Occasionally, the violence does not result in fistula, but in other genital injuries such as burns or damage to the pelvis.

Quite apart from the physical trauma, few ailments cause as much psychosocial and emotional discomfort and anguish as genital fistula.Citation10Citation11 These injuries are severe and long-term, with life-changing effects on the survivors and their communities. There is also a cultural barrier against acceptance of colostomy, urinary diversion or any surgery for irreparable fistula that requires abdominal stoma for discharge of bodily waste on a long-term basis.

The women who experience these injuries are sometimes neglected by their families, disowned by friends and rejected by their community, and they may even be abandoned by their own husbands. They suffer not only the stigma of fistula and stench of urine but also the stigma of rape; they are seen as “damaged goods”. Even worse, they might be labelled “enablers” or associates of their violators, therefore “traitors”. Furthermore, there is additional stigma when they have, or are suspected to have, HIV resulting from sexual assault, especially in the frequent absence of resources for HIV testing. The tragedy is compounded for young women in their childbearing years. They have a fierce desire to heal and to “get dry or die trying”.

Many of the women who survive gang-rape subsequently find themselves with an unplanned pregnancy or infected with serious STIs, including HIV. The HIV prevalence amongst armed combatants is believed to be much higher than in the general population.Citation1 Post-coital contraception and post-exposure prophylaxis for HIV are hopelessly out of reach for most of the populace. They may not even be considered, or may not be available or accessible within the recommended time frame.

There are broad societal implications of such widespread sexual violence to be gleaned from these case histories. Access to all manner of services that strengthen the fabric of civil society is severely curtailed. The education, health and justice systems are stretched to breaking point. There is little socio-economic or psychological support for “taboo” children born after rape or for their mothers. Re-integration of survivors and perpetrators into society is difficult because prevailing social norms are in fact outright abnormal and have been that way for decades. Much of the community is itself dysfunctional, and a new generation has been socialised into rape, war and pillage as the “norm”.Citation4

Armed combatants perpetrate sexual violence and atrocities amounting to crimes against humanity, with impunity. They are complacent in the knowledge that they will not be held to account, nor be pursued by local police or judicial authorities.

Recommendations

It will take more than a village to generate the necessary social and political will, motivation and resources to stop the murder of women in the DRC and eradicate sexual violence along with its aftermath, traumatic gynaecological fistula and genital injury.

It will require a coordinated, concerted international effort to secure peace and stability. The effort must be made by governments – DRC, Rwanda, donor governments and others – by UN agencies and mandated commissions, the Security Council, armed group commanders, humanitarian organisations, international media and advocacy groups. These groups will need to work together to:

greatly increase human and financial resources for supporting the infrastructure, judicial system (including protection of witnesses and rights groups), civil society and governance, to enforce governments’ obligations to meet international standards for due process and provide survivor compensation.

address the question of accountability and impunity of patrons and perpetrators of sexual atrocities and violation of women’s, children’s and men’s human rights.

ensure health system support for skilled clinical and other personnel with requisite infrastructure, equipment, supplies and logistical resources. Training in special sensitivity and patient-provider interaction is required, as well as specific ways of collecting and handling potential evidence, and strengthening counselling and psychosocial support for treatment and rehabilitation. Clinical sites need to offer confidential HIV counselling and testing, publicised and timely post-coital contraception and HIV post-exposure prophylaxis services at the lowest/nearest level of health care possible, followed by appropriate referral.

conduct clinical and operational research to develop best practices and approaches.

Finally, it will take greater political engagement by internal and external stakeholders to effect crucial improvement in peace and security, to hold all involved parties to account, and to dramatically increase humanitarian aid.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge the valuable support of colleagues and residents from Doctors on Call for Service/Heal Africa, and the DOCS Learning Centers at Goma, MSF/Kindu, EPVi/Beni and the Rector of “Grand Seminar” at Grabe-Butembo. The authors also appreciate the support of EngenderHealth, especially Karen Beattie, Lauren Pesso and Katherine Tell. The authors are especially indebted to the brave women, girls and families of the Eastern DRC who shared intimate details of their lives for this study.

References

- Human Rights Watch. The War within the War: Sexual Violence against Women and Girls in Eastern Congo. June. 2002; HRW: New York. At: <www.hrw.org/reports/2002/drc/. >.

- B Coghlan, RJ Brennan, P Ngoy. Mortality in the Democratic Republic of the Congo: a nationwide survey. Lancet. 367(9504): 2006; 44–51.

- VM Herp, V Parque, E Rackley. Mortality, violence and lack of access to healthcare in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Disasters. 27(2): 2003; 141–153.

- Addis Ababa Fistula Hospital; EngenderHealth/ACQUIRE Project; Ethiopian Society of Obstetrics and Gynaecology; Synergie de Femme pour les Victims de Violence Sexuelles. Traumatic Gynecologic Fistula: A Consequence of Sexual Violence in Conflict Settings. Meeting Report. Addis Ababa, 6-8 September 2005. At: <www.acquireproject.org/fileadmin/user_upload/ACQUIRE/Publications/TF_Report_final_version.pdf>.

- D Hinrichsen. Obstetric Fistula: Ending the Silence, Easing the Suffering. INFO Reports No.2. September. 2004; Baltimore: INFO Project, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

- RJ Cook, BM Dickens, S Syed. Obstetric fistula: the challenge to human rights. International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics. 87(1): 2004; 72–77.

- HM Mabeya. Characteristics of women admitted with obstetric fistula in the rural hospitals in West Pokot, Kenya. 2004; Geneva Foundation for Medical Education and Research: Geneva.

- K Roy, AM Vaijyanath, A Sinha. Sexual trauma: an unusual cause of a vesico-vaginal fistula. European Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology and Reproductive Biology. 101(1): 2002; 89–90.

- SR Singhal, S Nanda, SK Singhal. Sexual intercourse: an unusual cause of rectovaginal fistula. European Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology and Reproductive Biology. 131(2): 2007; 243–244.

- Obaid TA. Women, peace and security: responding to the needs of victims of gender-based violence. Statement to UN Security Council Open Debate on Security Council Resolution 132528. October 2004. At: <www.unfpa.org/news/news.cfm?ID=523>. Accessed May 2005.

- M. Bangser. Obstetric fistula and stigma. Lancet. 367(9509): 2006; 535–536.