Abstract

In Argentina adolescent pregnancy is still regarded as a public health problem or a “social epidemic”. However, it is necessary to ask from which perspective and for whom it is a problem, and what type of problem. This article presents the findings of a large quantitative and qualitative study conducted in five Northern provinces and two metropolitan areas of Argentina in 2003–2004. Based on the results of a survey of adolescent mothers (n=1,645) and ten focus group discussions with adolescent girls and boys, it addresses the connections between school dropout, pregnancy and poverty, and makes recommendations on how to tailor health care and sexuality education to address local realities. The findings indicate a need to develop educational activities to promote safer sex and address gender power relations in programmes working with deprived communities. Sexuality education with a gender and rights perspective, and increasing accessibility to contraceptive methods for adolescent girls and boys is also crucial. Antenatal and post-partum care, as well as post-abortion care, should be improved for young women and viewed as opportunities for contraceptive counselling and provision. Male participation in pregnancy prevention and care also needs to be promoted.

Résumé

En Argentine, les grossesses d’adolescentes sont encore considérées comme un problème de santé publique ou une « épidémie sociale ». Il faut néanmoins se demander dans quelle perspective et pour qui elles constituent un problème, et quel type de problème elles représentent. Cet article donne les conclusions d’une vaste étude quantitative et qualitative réalisée dans cinq provinces septentrionales et deux zones métropolitaines de l’Argentine en 2003–2004. Basé sur les résultats d’une enquête auprès de mères adolescentes (n=1645) et dix groupes de discussion thématique avec des adolescents des deux sexes, il aborde les relations entre l’abandon scolaire, la grossesse et la pauvreté et formule des recommandations sur l’adaptation des soins de santé et de l’éducation sexuelle aux réalités locales. Les programmes travaillant avec des communautés défavorisées doivent préparer des activités éducatives pour promouvoir des rapports sexuels protégés et aborder les relations de pouvoir entre hommes et femmes. Il est également crucial de dispenser une éducation sexuelle dans une perspective de droits et d’égalité entre les sexes, et de garantir aux filles et aux garçons un accès élargi aux méthodes contraceptives. Les soins prénatals et post-partum, ainsi que les soins après avortement, doivent être améliorés pour les jeunes femmes et considérés comme des occasions de les conseiller et de leur remettre des contraceptifs. La participation masculine à la prévention et aux soins de la grossesse doit aussi être encouragée.

Resumen

En Argentina, el embarazo en la adolescencia continúa percibiéndose como un problema de salud pública o una “epidemia social”. Sin embargo, es necesario preguntar de qué punto de vista y para quién es un problema, y qué tipo de problema. En este artículo se presentan los resultados de un estudio importante cuantitativo y cualitativo realizado en cinco provincias septentrionales y dos zonas metropolitanas de Argentina, en 2003–2004. Basado en los resultados de una encuesta entre madres adolescentes (n=1,645) y diez discusiones de grupos focales con niñas y niños adolescentes, el artículo trata las conexiones entre el abandono de estudios, el embarazo y la pobreza, y ofrece recomendaciones sobre cómo adaptar la educación sexual y la educación sobre la atención de la salud conforme a las realidades locales. Los hallazgos indican la necesidad de crear actividades educativas para promover relaciones sexuales más seguras y tratar las relaciones de poder entre los sexos en programas que trabajan con comunidades carenciadas. Es imperativo impartir educación sexual con un punto de vista de género y derechos, y ampliar el acceso de la adolescencia a los métodos anticonceptivos. Se debe mejorar la atención antenatal y posparto, así como la atención postaborto, para las mujeres jóvenes, y estos servicios deben verse como oportunidades para brindar consejería anticonceptiva y suministrar métodos anticonceptivos. Además, se debe promover la participación del hombre en la prevención y atención del embarazo.

In Latin America, pregnancy during adolescence became an issue in the 1970s, a decade later than in Europe and the United States. The construction of adolescent pregnancy as a “social problem” was the result of a variety of factors: the absolute and relative growth of the adolescent population, a smaller reduction in adolescent fertility than in adult women; the increased medicalisation of pregnancy and increased access to health care services by low-income sectors, which gave adolescent mothers greater social visibility; social and cultural changes; and particularly adults’ preoccupation with sexual activity among young people.Citation1–3

In Argentina, the adolescent fertility rate (age 15–19 years) is around 62 per 1,000, lower than the average rate of Latin America and the Caribbean (72.4 per 1,000), lower also than that of neighbouring countries Bolivia, Brazil, Paraguay and Uruguay, but significantly higher than Chile (43.6). Although the rate has steadily declined since 1980, when it peaked at 78 per 1,000, it has not yet fallen back to the levels observed at the beginning of the 1960s (58.4).Citation4

In order to better contextualise these data, it is worth taking into account that Argentina’s reproductive health indicators are relatively poor given the development of its public health system and the resources allocated to health (21.3% of the national budget). For instance, its maternal mortality rate (46 per 100,000 births) is higher than that of its neighbours Chile and Uruguay, countries that spend a lower proportion of their budgets on health care.Citation5

In addition, reproductive health indicators vary considerably between provinces. Despite the fact that regional differences in adolescent fertility rates have declined during the last decades, they continue to be high, currently ranging from 23.9 per 1,000 in the City of Buenos Aires to 100 per 1,000 in the provinces of Chaco and Misiones. Annually, around 100,000 children are born to teenage mothers in the country, representing 15% of total births. Adolescent motherhood is a repeated event for a great number of women: 32.5% of adolescent mothers aged 18–19 have more than one child, and 7.6% have three or more children.Citation4

Even though nowadays biomedical literature states that pregnancy is risky in biomedical terms only at a very early age (13–14 years),Citation6–10 the issue is still regarded as a public health problem or a “social epidemic” by public officials, physicians, the press and the general public. In addition, as Luker has shown for the US,Citation11 the common sense view still tends to regard adolescent pregnancy as a cause of poverty rather than as a consequence of it, and of the lack of resources and alternative projects.Citation1Citation2

There are certainly very diverse situations that fall into the category of adolescent pregnancy. In some cases, particularly among the youngest girls, pregnancy is the result of non-consensual sex (rape, incest, sexual coercion). In others, lack of sexuality education and friendly health care services, as well as gender inequalities, prevent teenagers from adopting contraceptive methods or using them effectively. Other adolescents actually seek or welcome pregnancy.

Taking “context” seriously into account, this article therefore aims at identifying priorities for action and providing useful data and ideas for the design of specific interventions that respond to the needs of different groups of adolescents. This is particularly relevant for Argentina, where there is a considerable disconnection between what researchers know and what decision-makers, politicians and the general public think are the facts about adolescent pregnancy. Our research has elicited adolescents’ perspectives and included the views of understudied social actors: young men, educational professionals, psychologists, social workers, youth and women’s health advocates. In order to complete the picture, we seek to consider the long-term impact of adolescent motherhood and fatherhood.Citation12–14

In short, we will try to provide some answers to the question from which perspective and for whom adolescent pregnancy is a problem, and what type of problem.Citation12

About the research project

This article summarises some of the results of a larger research project developed by CEDES (Centro de Estudios de Estado y Sociedad, Buenos Aires, Argentina) at the request of the National Ministry of Health and Environment, which supported the study together with UNICEF-Argentina.

CEDES took up this research at a very peculiar socio-economic and political time. Argentina was undergoing one of its most serious social, economical and political crises (2001/2002). 48% of the population were living in poverty, and the unemployment rate had reached 19%. In October 2002, soon after the Ministry of Health declared a “public health emergency”, the Senate finally approved a bill creating the National Programme on Sexual Health and Responsible Procreation within the National Ministry of Health (Law 25.673). This was a turning point and a significant step forward since, for the first time in decades, the State officially acknowledged that sexual and reproductive health issues were a priority and showed political will to implement actions in this field. The fact that the adolescent fertility rate was high in many Northern provinces and that adolescent motherhood is a repeated event for a great number of teenagers motivated the official request for evidence to better inform policy.

The project was carried out in the capital cities of five poor northern provinces – Salta, Misiones, Chaco, Tucumán and Catamarca – and the two largest metropolitan areas – Buenos Aires and Rosario – between August 2003 and July 2004. It aimed at updating relevant data, filling information gaps and understanding the perspectives of relevant stakeholders (policymakers, health care providers, male and female adolescents). Sites were selected taking into account adolescent fertility rates, the proportion of deliveries in women aged 15–19 to total deliveries and other key reproductive health indicators (e.g. maternal and infant mortality). The final purpose was to inform policies and programmes aimed at preventing unplanned adolescent pregnancy and its repetition and improving the quality of health care provided to pregnant teens.

The study had two main components. First, a socio-demographic analysis based on special tabulations of the last national census (2001) and vital statistics.Citation4 Second, a local situational diagnosis that was built upon:

Interviews with key informants (managers from Health, Education and Social Development Departments, Women’s and Youth Secretaries, health care providers and NGO representatives and community leaders). We explored their opinions regarding the main problems adolescents face and particularly their perspectives on adolescent pregnancy, motherhood and fatherhood and strategies to prevent or address the issue.

A survey among young women aged 15–19 who had just given birth in 14 public health sector facilities in the study sites during the two months from December 2003 to February 2004. In each capital city, interviewees were recruited in the principal hospital where the vast majority of adolescent mothers give birth. In Rosario, the survey was conducted in a municipal hospital that accounts for half of the deliveries of women aged 15–19. In the metropolitan area of Buenos Aires, six hospitals were selected from different health regions with high adolescent pregnancy rates. Approximately 30% of pregnant adolescents from these regions give birth in the selected hospitals. The questionnaire had six modules: pregnancy and birth care; reproductive history; contraceptive knowledge and method use; situation at the time of the first live birth; expectations for the future and socio-demographic profile. It was administered by women health workers, mostly midwives, who were trained on-site and later supervised by CEDES researchers. For ethical reasons, adolescents whose babies or who themselves were in the intensive care unit, adolescents whose babies were stillbirths or those with a mental disorder were not invited to participate in the survey. Informed consent, explaining the purpose of the study and asking for their participation, was obtained from all interviewees.

Focus groups with male and female adolescents (with and without children), conducted by same sex CEDES researchers, were used to explore teenagers’ views and experiences regarding contraception, abortion, pregnancy and motherhood and fatherhood. Some results from the survey of young mothers were also discussed in the focus groups to improve our understanding of their meaning.

Based on the survey and the focus group findings, this article addresses the connections between school dropout, pregnancy and poverty, reconstructs adolescents’ reproductive stories and makes recommendations on how to tailor health care and sexuality education to address local realities. Additionally, we highlight how the data help to deconstruct some deeply-rooted stereotypes.

Survey and focus group participants

Of a total of 1,881 deliveries of adolescents aged 15–19 that took place in the study period, 1,645 young women were surveyed. Of the 236 who were not interviewed, 183 fell into the pre-established exclusion criteria, 45 left the hospital before they could be contacted by the interviewer and eight refused to participate.

The average age of the respondents was 17.5; 57% were ages 18 and 19. Some 36% had complete primary school or less; 52% had not completed secondary school and 12% had completed secondary school or more. More than half (55%) lived in overcrowded conditions (three or more people per room) and in 22% of these cases there were four or more per room. Two out of three lived with a partner, whether in a nuclear household or with other relatives and non-relatives. The proportion who lived with a partner was 68.7% among those aged 18 and 74.3% among those aged 19. 74% were primiparous.

Sixty-five adolescents aged 15–20 participated in focus groups. Three were with adolescent mothers and three with adolescent fathers, and four groups were with adolescents who did not have children (two with girls and two with boys) in three sites (a north-western city, a north-eastern city and in the Greater Buenos Aires Area). There were four to ten adolescents in each group. They were invited to participate through local organisations that carry out activities with teenagers and through primary health care centres.

Findings

Adolescent mothers and their partners

Contrary to the common belief that teenaged girls who have children experience motherhood alone, vital statistics show that an important proportion of adolescent mothers were living with a partner when they registered their newborns: 42% of those who were 14 or younger, 52% of those aged 15–17 and 71% of those aged 18–19. Census data (2001) also shows that half of teenage mothers were living with their spouse or consensual partner. Consistently, data from the Survey of Life Conditions (2001) show that 47% of mothers aged 15–19 were married or lived with a partner, 10% were divorced or separated and 44% were single.Citation15

Our survey data on adolescent partnership status showed that 41% of young women were already living with their partners at the time of conception, while 55% became pregnant in the context of a dating relationship. By the time the baby was born, 62% were living with a partner, 20% were still dating the father and 10% of relationships had ended. This suggests that pregnancy and birth occur in various partnership contexts, and that pregnancy causes an important number of dating relationships to turn into marital or cohabiting unions. In general, adolescent mothers have children with men of a similar age or a few years older. Only a minority of the adolescents interviewed (5%) said that the father of their child was aged 30 or older. This is similar to data reported in the local literature.Citation16–18

Pregnancy and schooling

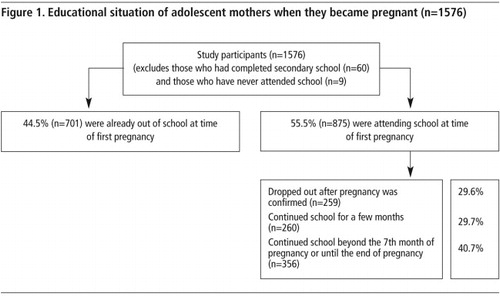

Vital information, previously lacking, to address the relationship between pregnancy and school dropout was collected by the survey. It revealed that 44.5% of young mothers were already out of school at the time of their pregnancy (), with significant variations between sites, ranging from 28% to 68%.

Not attending school at the time of becoming pregnant (which on average occurred at age 16.6) was related to schools’ low capacity to encourage students to stay in school (55% of the girls who had dropped out before they got pregnant said they did not want to be in school anymore or had difficulties with studying), economic and accessibility problems (29%) or domestic responsibilities (8%).Footnote*

In addition, data collected shows that nearly one-third of the adolescents (and half in Tucumán, a very poor north-western province) were neither studying nor working at the time they became pregnant with their first child. This reinforces the idea already proposed by several local authors that, in contexts in which young people have very limited expectations, motherhood is considered a positive experience.Citation19–21 For instance, López states that motherhood is the principal source of social recognition, self-esteem and respect from family and community for adolescent women living in poor socio-economic conditions.Citation15

What happened with those who were still attending school when they became pregnant? Six out of ten dropped out during the subsequent months. Feeling ashamed of going to school pregnant and fearing discrimination was the most mentioned reason for dropping out (28%). The second most mentioned reason was not wanting or not liking to study (16%), which could be evidence of poor performance or learning difficulties. In this sense, a study of high school dropout concluded that for adolescents in marginal and vulnerable contexts, pregnancy rarely cuts short a moderately successful educational career and that, in many cases, pregnancy precipitates a decision to quit school that had previously been considered.Citation22 Other reasons reported included the prescription of bed rest (14%), economic problems (8%) and accessibility problems (7%) such as night school, long distances and bad weather conditions, particularly in the poorest sites.

As regards schools’ policies, 5% of interviewees said that their school did not admit or expelled pregnant students. On the other hand, four out of ten adolescents who were attending school continued to do so until the end of pregnancy (or at least beyond the seventh month). Focus group discussions showed that in many cases the school appeared to be a flexible environment that, even when lacking the appropriate infrastructure, adapted itself to pregnant adolescents’ and young mothers’ needs (i.e. small children and babies were allowed into classes and mothers could leave class to breastfeed). Some of the girls appreciated their teachers’ concern with their health and well-being as well as their child’s.

This evidence is consistent with data from other countries in the region,Citation2 and calls into question the stereotyped assumption of an automatic causal relationship between adolescent pregnancy and school dropout.

Contraceptive use when conception occurred

The majority of survey participants (82%) were not using a contraceptive method at the time they became pregnant, even when they did not necessarily want a child. Among those who were primiparous,Footnote* the most mentioned reason for not having used contraception was “wanted to have a baby” (44%), ranging from 30–60% between sites. The proportion who wanted to become pregnant was bigger among girls aged 18–19 years (48%) than among those aged 15–17 (38%). It was 50% among those who were not in school (independently of whether they had finished secondary school or not) compared to 38% among those in school, and higher among those who were living with a partner (58%) than among those not living with a partner (33%). Focus group data indicated that adolescents who intentionally try to get pregnant are usually experiencing particular life circumstances such as feeling lonely after the death of a loved one, having lost a previous pregnancy (either due to a spontaneous miscarriage or an induced abortion), living with a partner or having been dating during a period of time they considered long enough to start a family.

Other main reasons for not having used contraception were poor knowledge (19% thought they could not become pregnant), lack of information on or access to contraceptives (11%), unexpected intercourse (10%) and partners’ refusal to use contraception (7%). Gender norms and the ideology of romantic love underlie many of these reasons, as the literature has repeatedly pointed out.Citation15

Adolescents’ reproductive histories as well as official data on the number of adolescents hospitalised due to complications of unsafe abortions show that termination of pregnancy is frequent among adolescents. Even though abortion is legally restricted, approximately 5% of survey participants said they had had an abortion, of which 62% were of a first pregnancy, 29% a second one, 8% a third and 1% a fourth pregnancy.

Focus group discussions revealed that when girls find out they are pregnant they usually feel ashamed and afraid of their parents’ reactions and often attempt to terminate the pregnancy as a way to avoid tension with adults, rather than as a direct rejection of motherhood. Usually these attempts involve ineffectual methods such as hormonal injections bought over the counter or ingestion of home-made herbal preparations.

Antenatal care

Nearly 4% of teens surveyed did not have a medical check-up at all during pregnancy, and an additional 3% had only one. The most frequent reason mentioned (40%) was that they lacked access to health care services (i.e. long distances, did not have money to pay for transportation, did not have time), followed by not considering it important or not wanting to receive medical care during pregnancy (26%).

The majority (69%) had at least five check-ups, which is the number promoted by the Ministry of Health, though a 2003 WHO document recommends that four check-ups are enough.Citation23Citation24 Primiparous young women were more likely to have an adequate number of check-ups (75%) than multiparous women (52%). Education played a significant role in having an adequate number of check-ups. Other variables such as poverty status, school attendance and having used contraception quite consistently were also significant predictors of adequate antenatal care mainly among primiparous mothers. Multivariate analysis found that among primiparous young mothers, educational level and poverty level had an independent effect on antenatal care.Footnote* At each educational level, adolescents living in the poorest households were less likely to have five or more antenatal check-ups. Furthermore, those who were going to school at the time they got pregnant were 34% more likely to have an adequate number of antenatal visits than those who had already left school.

Reproductive history and the context in which pregnancy occurs also influenced attitudes towards antenatal care, with those who reported having used contraception from first sexual intercourse, those who wanted to have a baby, and those who were in a dating or cohabiting relationship at the time they got pregnant having a higher probability of having had an adequate number of antenatal check-ups.

Regarding the timing of antenatal check-ups, 56% started in the first trimester and 37% in the second trimester. Early antenatal care was higher for primiparous (60%) than multiparous girls (46%). Focus group discussions suggested that mixed feelings about whether or not to continue the pregnancy, fear of disclosing their status and self-induced attempts to terminate the pregnancy may explain the delay in initiation of antenatal check-ups.

Girls usually attended antenatal care in the company of significant others (75%), the majority (61%) with their partners. Focus group discussions with young fathers indicated that they were interested and willing to attend as a way of showing concern for their partners and babies, and also to clarify doubts and get first-hand information about the progress of the pregnancy. Some young men expressed gratitude towards health professionals who encouraged their participation, since this allowed them to some extent to feel “protagonists” in the process as well. Those who had not been able to attend check-ups due to their working hours expressed regret. Also, young fathers who had been unable to be with their partners during delivery or at night due to hospital regulations expressed feelings of frustration and anger. This strong will to be present during pregnancy and delivery should not be taken as indicative of active participation during childrearing, however.

With respect to characteristics and quality of antenatal check-ups, nearly all young mothers reported having received routine screening, such as blood pressure, weight, stomach measure, listening to baby’s heart, ultrasound and tetanus shot. 70% said they were tested for HIV. Only one out of three received information about breastfeeding and contraceptive counselling, and only 8% attended a birth preparation course. The vast majority reported there were no such courses offered in public sector facilities, or they lacked such information (63%).

In the immediate post-partum period, 58% of teen mothers received information on breastfeeding, 54% were advised how to take care of the baby (i.e. bathing, cleaning the umbilical cord), but only 30% received information on family planning. This last figure is extremely low when compared to the fact that nine out of ten interviewees reported they were willing to use contraception in the near future, and wanted to space their next pregnancy by at least two years. The preferred contraceptive methods were oral contraceptives (45%), IUD (36%), injectable contraceptives (9%) and condoms (7%). Although the condom had been the most commonly used method among them before the pregnancy, an effective female-controlled contraceptive method had become their priority. Yet physicians in public hospitals were often reluctant to provide an IUD to adolescent mothers, believing it to be risky if they do not return in case of complications and also because it discourages the use of condoms to prevent STIs/HIV.

Discussion and recommendations

The data generated by this study enabled us to see whether and for whom adolescent pregnancy among 15–19 year-old girls was a problem and what type of problem. We found that 40–70% of adolescent mothers in our study would have preferred to postpone pregnancy. Unwanted pregnancy entails the risk of unsafe abortion, which causes maternal morbidity and mortality. If the unwanted pregnancy is carried to term, however, subsequent problems include having to leave school to perform domestic chores, take care of the child, perhaps without adequate resources, increased difficulties accessing work, interruption of personal development and limitations on future opportunities.

• Preventing adolescent pregnancy

Our findings are consistent with those of other research showing that social and economic disadvantage plays a powerful role in teenage pregnancy and childbearing.Citation11 Thus, socio-economic policies aimed at the social inclusion of adolescents from underprivileged groups are crucial, particularly in a country in which, at the moment we conducted the study, 63% of children aged 0–13 and 58% of those aged 14–22 were living in poverty.Citation25

Better economic and social conditions would allow teenagers to remain in school and to envisage opportunities for employment and personal development other than having children. Keeping adolescents in school is key to their well-being and to prevent unwanted pregnancies. As shown above, longer schooling is clearly associated with the adoption of contraception at sexual initiation and attending antenatal care. It seems that contact with teachers, peers and authorities and the expectation that educational credentials may help them find a job or be better prepared to face adult life encourages “protective behaviours”.Citation22 Our findings indicate that the response of schools to pregnant adolescents and mothers tend to depend to a large extent on individual initiative and commitment on the part of teachers and heads of schools. Thus, the Ministry of Education needs to issue guidelines to require all schools to fulfil the rights guaranteed to pregnant students and mothers by existing national laws (National Laws 25.808 and 25.273).

Even in the optimist scenario of an improvement of people’s living conditions and opportunities, some of the public policy deficits identified will not automatically be redressed. Some specific interventions need to be implemented or reinforced and expanded.

As the literature has consistently shown, our findings indicate that adolescents find it difficult to practise safer sex due to gender images, roles and power relations, the “ideology of romantic love” and persistent myths regarding contraception.Citation26Citation27 Thus, it is imperative to implement sexuality education at schools and communities. The recently approved National Law 26.150/2006, which makes sexuality education mandatory at all school levels, provides a window of opportunity to address a pending and highly controversial issue in Argentina.

One important experience from other countries in the region for Argentina to learn from is that behaviour change, condom use and safer sex should be part of programmes in deprived communities rather than exclusively school-based education.Citation26 Emphasis on community-level work is particularly appropriate for contexts where a high proportion of adolescents are not in the educational system. The local diagnoses we conducted (data from this study, not shown here) indicate that it is necessary to train sex educators from a gender and rights perspective and using participatory approaches. Gender equity and gender and sexual violence are some of the key topics that need to be addressed by adolescents, parents and community leaders.

• Improving quality of maternity care and post-abortion care

In order to improve the coverage of antenatal care, it is important to carry out public information campaigns promoting antenatal check-ups and facilitate access to health care centres in terms of improved clinic hours and ease of getting appointments. Local health care units and community leaders need to target multiparous young women with a low educational level, since they are the group with the lowest antenatal care coverage.

Another aspect for improving quality of obstetric care that any strategy must address is the lack of birthing classes. Our focus groups indicated that delivery and post-partum are times when men’s presence is forbidden or not encouraged and their desire for involvement underestimated. It is essential that institutions reconsider the way they are excluding young fathers.

Contraceptive and breastfeeding counselling need to be included as routine practices during antenatal care, in order to improve quality of care. Follow-up of young women after delivery or post-abortion also clearly needs to be improved. Post-partum care and healthy child visits can be good opportunities to offer contraceptive information and methods to young mothers. Given the willingness we found to space pregnancies and the wish to have only a small number of children, a wide range of methods should be available. The prevailing guidance discouraging IUD provision to adolescents must be reviewed, especially for those with previous failures with male-controlled and hormonal methods (data from this study, not shown here).

Regarding post-abortion care, it is important to improve interpersonal relations between health care providers and patients in view of the prejudices and stigma elicited in interviews with some health care providers (data from this study, not shown here). The context for such interventions is favourable since the Ministry of Health is committed to improving post-abortion quality of care (i.e. carrying out training in manual vacuum aspiration). Contraceptive counselling should be offered as a routine practice to women hospitalised due to abortion complications. More globally, it is necessary to support initiatives to make abortion legal since that would contribute to reduced morbidity and mortality from unsafe abortions.

As with sex educators, health professionals need to be sensitised to a gender and rights perspective. In particular, it is important that they show a greater understanding of the difficulties that consistent and correct use of contraception entails and thus, be more willing to offer emergency contraception and IUDs.

In conclusion, even though the implementation of sexuality education and the provision of contraceptive methods to adolescents still face political, ideological, institutional and cultural resistance, the current scenario is favourable for the enhancement of adolescents’ sexual and reproductive health and rights. We hope that the research data produced by this study and the recommendations it has inspired may contribute to the development of more humane and appropriate interventions that take into account adolescents’ perspectives, needs and desires.

Acknowledgements

This paper is based on research published in the book Embarazo y maternidad en la adolescencia. Estereotipos, evidencias y propuestas para políticas públicas. The research was funded by the National Ministry of Health and Environment of Argentina and UNICEF Argentina. We thank Dr O’ Donnell, former Director, National Research Commission for Health Research, and Eleonor Faur, former UNICEF officer, for their commitment to the project and the dissemination of research results at the national level. We acknowledge the research contributions of Ariel Adaszko, Valeria Alonso and Fabián Portnoy and of Edith Pantelides to the demographic analysis. Fieldwork was carried out by local scholars: Lidia Mobilio (Chaco), Silvia Nudelman and Raúl Claramunt (Misiones), Mara Duhart (Catamarca), Paola Andreatta and Marta Arrascaeta (Buenos Aires), Evelina Chapman (Tucumán), Silvia Yocca de Sabio (Salta) and Fernanda Candio (Rosario). We are grateful to the midwives who administered the survey with efficiency and sensitivity.

Notes

* The remaining 8% corresponds to other reasons or without data.

* For ethical and methodological reasons we did not ask directly “Was this a wanted pregnancy?”. Instead, we asked if they were using contraception or not at the moment they got pregnant with this baby and why. Indirectly, this gave us information on whether – at the time of conception – these pregnancies had been wanted or not. These data were collected only for primiparous women. Multiparous had their first pregnancies at least two years before and we wanted to avoid biases caused by the time gap or the experience of motherhood.

* We are referring to multivariate logistic regression models that predict the odds of having at least five check-ups during pregnancy separately for primiparous and multiparous mothers. Other control variables included place of residence, private or social security health care coverage and age at sexual initiation (which was not statistically significant).

References

- C Stern, E García. Hacia un nuevo enfoque en el campo del embarazo adolescente. C Stern, JG Figueroa. Sexualidad y Salud Reproductiva. Avances y Retos para la Investigación. 2001; El Colegio de México: México DF, 331–358.

- E Pantelides. Aspectos sociales del embarazo y la fecundidad adolescente en América Latina. CELADE-Université Paris X Nanterre. La Fecundidad en América Latina y el Caribe: Transición o Revolución?. 2004; CELADE-UPX: Santiago de Chile, 167–182.

- ML Heilborn, E Aquino, D Knauth. Editorial. Cadernos de Saúde Pública. 22(7): 2006; 1362.

- Binstock G, Pantelides E. La fecundidad adolescente hoy: diagnóstico sociodemográfico. In: Gogna M, coordinator. Embarazo y Maternidad en la Adolescencia. Estereotipos, Evidencias y Propuestas para Políticas Públicas. Buenos Aires: Cedes-UNICEF-Ministerio de Salud de la Nación, 2005. p.77-112.

- M Gogna, N Zamberlin. Sexual and reproductive health in Argentina. Public policy transitions in a context of crisis. Journal of Iberian and Latin American Studies. 10(2): 2004; 95–105.

- D Lawlor, M Shaw. Too much too young? Teenage pregnancy is not a public health problem. International Journal of Epidemiology. 31(3): 2002; 552–554.

- G Scally. Too much too young? Teenage pregnancy is a public health, not a clinical problem. International Journal of Epidemiology. 31(3): 2002; 554–555.

- J Rich-Edwards. Teen pregnancy is not a public health crisis in the United States. It is time we made it one. International Journal of Epidemiology. 31(3): 2002; 555–556.

- S Smith. Too much too young? In Nepal more a case of too little, too young. International Journal of Epidemiology. 31(3): 2002; 557–558.

- Román Pérez R, Vázquez Pizaña E, Rojo Quiñones G, et al. Riesgos biológicos del embarazo adolescente: una paradoja social y biológica. In: Stern C, García E, coordinators. Sexualidad y Salud Reproductiva de Adolescentes en México. Aportaciones para la Investigación y la Acción. Documentos de Trabajo 6. México DF: El Colegio de México, 2001. p.33-58.

- K Luker. Dubious Conceptions. The Politics of Teenage Pregnancy. 1996; Harvard University Press: Cambridge.

- ER Brandão, ML Heilborn. Sexualidade e gravidez na adolescência entre jovens de camadas médias do Rio de Janeiro, Brasil. Cadernos de Saúde Pública. 22(7): 2006; 1421–1430.

- Weller S. Salud reproductiva de los/las adolescentes. Argentina, 1990-1998. In: Oliveira MC (organiser). Cultura, Adolescência, Saúde: Argentina, Brasil, México. Campinas: Cedes-Colmex-Nepo/Unicamp, 1999. p.9-43.

- A Villa. Identidades masculinas y comportamientos reproductivos entre varones de los sectores populares pobres de Buenos Aires. JG Figueroa, R Nava. Memorias del Seminario-Taller Identidad Masculina, Sexualidad y Salud Reproductiva. 2001; El Colegio de México: México DF, 27–31.

- E López. La fecundidad adolescente en la Argentina: desigualdades y desafíos. UBA: Encrucijadas, Revista de la Universidad de Buenos Aires. 39: 2006; 24–31.

- E Pantelides. La Maternidad Precoz: la Fecundidad Adolescente en la Argentina. 1995; UNICEF: Buenos Aires.

- MC Añaños. Composición y comportamientos de unión en madres adolescentes. Rosario 1980–1991. Cedes-Cenep, Taller de Investigaciones Sociales en Salud Reproductiva y Sexualidad. 1993; Cedes-Cenep: Buenos Aires.

- RN Geldstein, EA Pantelides. Double subordination, double risk: class, gender and sexuality in adolescent women in Argentina. Reproductive Health Matters. 5(9): 1997; 121–131.

- Adaszko A. Perspectivas socio-antropológicas sobre la adolescencia, la juventud y el embarazo. In: Gogna M, coordinator. Embarazo y Maternidad en la Adolescencia. Estereotipos, Evidencias y Propuestas para Políticas Públicas. Buenos Aires: Cedes-UNICEF-Ministerio de Salud de la Nación, 2005. p.33-66.

- Zamberlin N. Percepciones y conductas de las/los adolescentes frente al embarazo y la maternidad/paternidad. In: Gogna M, coordinator. Embarazo y Maternidad en la Adolescencia. Estereotipos, Evidencias y Propuestas para Políticas Públicas. Buenos Aires: CEDES-UNICEF-Ministerio de Salud de la Nación, 2005. p.285-316.

- RN Geldstein, EA Pantelides. Riesgo Reproductivo en la Adolescencia. Desigualdad Social y Asimetría de Género. 2001; UNICEF: Buenos Aires. At: <www.unicef.org/argentina/spanish/ar_insumos_Riesgoreproductivoadolescencia.pdf. >.

- G Binstock, M Cerrutti. Carreras Truncadas. El Abandono Escolar en el Nivel Medio en la Argentina. 2005; UNICEF: Buenos Aires.

- Ministerio de Salud de la Nación. El Cuidado Prenatal. Guía para la Práctica del Cuidado Preconcepcional y del Control Prenatal. 2001; Ministerio de Salud de la Nación: Buenos Aires.

- Organización Mundial de la Salud. Ensayo Clínico Aleatorizado de Control Prenatal de la OMS: Manual para la Puesta en Práctica del Nuevo Modelo de Control Prenatal. 2003; WHO: Geneva.

- Instituto Nacional de Estadísticas y Censos. Permanent Household Survey. 2003, second semestre. At: <www.indec.gov.ar. >.

- V Paiva. Gendered scripts and the sexual scene: promoting sexual subjects among Brazilian teenagers. R Parker, RM Barbosa, P Aggleton. Framing the Sexual Subject. The Politics of Gender, Sexuality and Power. 2000; University of California Press: California, 216–239.

- Heilborn ML, Aquino EML, Bozon M, et al, organizers. O Aprendizado da Sexualidade: Reprodução e Trajetórias Sociais de Jovens Brasileiros. Rio de Janeiro: Editora Garamond/Editora Fiocruz, 2006.