Abstract

This article draws on a study conducted by the Women and Media Collective between 2004 and 2005 to highlight some of the reproductive health concerns of women from Sinhalese, Tamil and Muslim ethnic groups, living in situations of conflict in Sri Lanka. The study focussed on women from six conflict-affected areas in the north and east of the country: Jaffna (Northern Province), Mannar and Puttalam (North-Western Province), Polonnaruwa (North-Central Province), Batticaloa and Ampara (Eastern Province). Higher levels of poverty, higher rates of school drop-out, low pay and precarious access to work, mainly in the informal sector, higher rates of early marriage, pregnancy and home births, higher levels of maternal mortality and lower levels of contraceptive use were found. Economic, social and physical insecurity were key to these phenomena. Physically and psychologically, women were at high risk of sexual and physical violence, mainly from their partners/spouses but also from family members, often related to dowry. The article brings out the voices of women whose lives have been overshadowed by conflict and displacement, and the nature of structural barriers that impede their right to health care services, to make informed decisions about their lives and to live free of familial violence.

Résumé

De 2004 à 2005, Women and Media Collective a réalisé une étude pour mettre en lumière certaines préoccupations de santé génésique des femmes issues de groupes ethniques musulmans, tamouls et singhalais qui vivent dans une situation de conflit à Sri Lanka. L’étude portait sur les femmes dans six zones touchées par le conflit au nord et à l’est du pays : Jaffna (province du Nord), Mannar et Puttalam (province du Nord-Ouest), Polonnaruwa (province du Centre-Nord), Batticaloa et Ampara (province de l’Est). Elle a constaté des niveaux plus élevés de pauvreté, des taux supérieurs d’abandon scolaire, de faible rémunération et d’accès précaire à l’emploi, principalement dans le secteur informel, des taux plus importants de mariage précoce, de grossesse et de naissance à domicile, des taux supérieurs de mortalité maternelle et des niveaux moindres d’utilisation des contraceptifs. L’insécurité économique, sociale et physique était au centre de ces phénomènes. Physiquement et psychologiquement, les femmes couraient des risques importants de violence physique et sexuelle, surtout de leur partenaire/conjoint, mais aussi de membres de leur famille, souvent en rapport avec la dot. L’article fait entendre la voix des femmes dont la vie a été assombrie par le conflit et le déplacement, et montre la nature des obstacles structurels qui contrarient leur droit de bénéficier de services de santé, de prendre des décisions éclairées sur leur vie et d’être protégées de la violence familiale.

Resumen

Este artículo se basa en un estudio realizado por el Women and Media Collective entre 2004 y 2005 para destacar algunas de las inquietudes respecto a la salud reproductiva entre mujeres provenientes de los grupos étnicos sinalés, tamil y musulmán, que viven en situaciones de conflicto en Sri Lanka. El estudio se centró en mujeres de seis zonas afectadas por conflicto, en el norte y este del país: Jaffna (Provincia Septentrional), Mannar y Puttalam (Provincia Septentrional-Occidental), Polonnaruwa (Provincia Septentrional-Central), Batticaloa y Ampara (Provincia Oriental). Se encontraron niveles más altos de pobreza, tasas más altas de abandono de estudios, baja paga y acceso precario a empleo, principalmente en el sector extraoficial, tasas más altas de matrimonio, embarazo y partos domiciliares a temprana edad, niveles más altos de mortalidad materna y niveles más bajos de uso de anticonceptivos. Estos fenómenos son producto de la inseguridad económica, social y física. Física y psicológicamente, las mujeres corrían un alto riesgo de violencia sexual y física, principalmente de sus parejas/cónyuges pero también de familiares, a menudo relacionada con la dote. El artículo transmite las voces de mujeres cuya vida ha sido eclipsada por conflicto y desplazamiento, así como la naturaleza de las barreras estructurales que impiden su derecho a servicios de salud, a tomar decisiones informadas sobre su vida y a una vida libre de violencia intrafamiliar.

This paper analyses the experiences of women living in areas of Sri Lanka that have been affected by armed conflict for more than two decades. It draws on women’s shared experiences of accessing health services, and of the familial and social relationships that have mediated aspects of their well-being related to reproductive health. Their stories give insights into structural factors that impede their well-being – such as negative socio-cultural practices and values in their homes and communities, as well as the challenges of being displaced or living through armed conflict. These experiences exemplify why reproductive health is not merely a health issue to be solved through better health services.

Following the International Conference on Population and Development (ICPD) in 1994, Sri Lanka formulated a National Population and Reproductive Health Policy in 1998 and embarked on several policy and programme initiatives in line with the declared objectives of the ICPD Programme of Action.Citation1 This signalled a shift in focus from mere demographic goals to an emphasis on reproductive health, reproductive rights and women’s empowerment for meeting the needs of the people.Citation2 Sri Lanka’s achievements in population and family planning are perceived as a success. For example, in 2002, the total fertility rate and population growth rate were 1.93 and 0.85, respectively. The contraceptive prevalence rate was 70%, the infant mortality rate was 10.2 for female infants and 12.9 for male infants per 1,000 live births, while the maternal mortality ratio was as low as 27.5 per 100,000 live births.Citation3Citation4

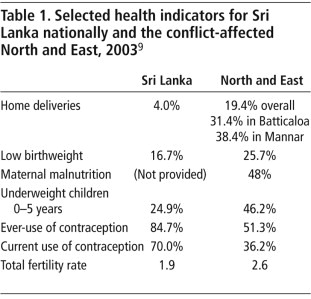

These statistics notwithstanding, there are reproductive health issues to be explored and addressed, particularly among those living in conflict-affected areas of the country. In Sri Lanka, there has not been a comprehensive island-wide population census carried out since 1981. The current study of six conflict-affected districts uses national-level data where available and draws on research studies on socio-economic issues in conflict-affected areas for comparative purposes.

The six districts surveyed for this research were found to have a significantly higher proportion of population living in poverty in 2002 compared to the national average of 22.7% (23.0% for males and 21.5% for females).Citation5Citation6 In Puttalam, for example, the proportion of the population living below the poverty line in 2002 was 31.4% of men and 30.8% of women, while in Polonnaruwa it was 24.1% of men and 22.1% of women. In Amapara, it was estimated that as many as 65% of the population were living below the poverty line.Citation7

School drop-out rates in the conflict-affected districts also indicate the impact of long-term disruption of education in these areas. For example, in 2000 while the drop-out rates for girls in years 1-10 was 2.16% at the national level, in Batticaloa, Ampara, Puttalam and Polonnaruwa it was found to be 4.62%, 3.76%, 3.96% and 3.52%, respectively.Citation8

Impact of the conflict on health and health services

Sri Lanka’s ethnic conflict, which has been both protracted and brutal, has destroyed lives and livelihoods as well as property and the environment, and has led to heightened polarisation and separation between the different ethnic, linguistic and religious groups living on the island. There are several thousand families who have been internally displaced for almost two decades.

Baseline assessments of health services in the war-affected North and East showed a significant disruption of preventative and curative health services. A WHO study revealed that human resources shortages, in addition to the absence of basic health infrastructure, contributed to the dismal health situation during this period. Reproductive health services were found to be seriously affected, with the lack of emergency obstetric facilities in peripheral hospitals particularly highlighted, and maternal morbidity and mortality were estimated to be higher than in other parts of the country.Citation9

The 2003 Needs Assessment for the Sub-Committee on Immediate Humanitarian and Relief Needs (SIHRN)Footnote* provides useful indicators on the reversal of earlier national level achievements in good health care in the conflict-affected North and East. It showed that in the North East there was a severe shortage of medical officers, basic specialists and certain paramedical workers, with 34% of 9,542 posts for skilled health cadre vacant in these areas.Citation10 It also served to highlight the very gender-specific consequences of the depletion of health and reproductive health services to the North and East and the effects on women’s lives.

Scope and methodology

The research was carried out in 2004–2005 in the districts of Jaffna (Northern Province), Mannar and Puttalam (North-Western Province), the border villagesFootnote† in Polonnaruwa (North-Central Province), Batticaloa and Ampara (Eastern Province). The districts were selected on the basis that they were affected by the conflict, either directly through military encounters between the LTTE and the Sri Lanka armed forces or through the large-scale entry of displaced communities from other areas as a result of the conflict.

The research methodology and framework were drawn up by the Women and Media Collective (WMC). Data collection was facilitated by representatives of community-based organisations, comprising women activists and graduates with experience in participation in research projects, who had a strong focus on women’s concerns and well-established relationships with communities in the respective districts. Training on data collection and methodology was provided by WMC with assistance from professional trainers in gender and health research.

The first phase consisted of random sampling where every fifth house was interviewed in

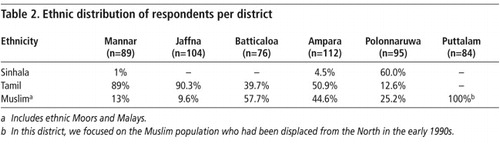

selected village locations. We aimed at capturing the main age cohorts in which women’s reproductive health issues became visible, which are also the focus of most institutional and social interventions. The sample from all districts comprised 560 women. Accessing and completing interviews with a 100 women in each district, as originally planned, had to be modified to accommodate realities prevailing on the ground in these areas. The total number of completed interviews from each district was as follows: Mannar 89, Jaffna 104, Batticaloa 76, Ampara 112, Polonnaruwa 95 and Puttalam 84.A structured questionnaire was then administered. In the second phase, in-depth interviews with 30 women who had answered the questionnaire, selected on the basis of ethnicity and age, were carried out.

Finally, six regional focus group discussions were held with representatives of women’s groups, organisations working on women and health issues, medical personnel, family health workers, graama sevakas (village-level government administrators) and police officers in the six districts.

Respondents

The research focus was to reflect the ethnic distribution of the population in the districts, a breakdown of which is shown in Table 2.

Of the total sample, 44% were aged 19-40, 15.7% were aged 12-18 years and 39.5% were aged 41-60 years. These age cohorts were decided upon after consultations with key informants in the reproductive health sector. Most of the respondents were married (70.7%). Unmarried women, i.e. those who had never cohabited with a partner or spouse at the time of the interview, comprised 21.2% of the sample, while 7.2% were either widowed or divorced.

Socio-economic and cultural background: impact on women’s reproductive health

Studies in South Asian societies have shown how socio-behavioural norms often deprive women of access on equal terms with men to food in their own homes, education and higher learning, mobility and involvement in decision-making.Citation11Citation12

Most of the women were engaged primarily in household-related activities or work available in the informal sector, such as daily work as housemaids in better-off households, daily paid agricultural work, sewing, preparing and selling food from the home, and fishing-related activities such as cleaning nets and drying fish.Citation13 In the Muslim communities in particular, but also among the Sinhalese and the Tamils, some women had previously migrated to West Asia for short-term employment as housemaids. A significant number of female-headed households were recorded, especially in the Batticaloa district sample.

In the Polonnaruwa sample, 28.5% received Samurdhi (state welfare subsidy for the poor), while 11.6% received other government welfare assistance intended specifically for those who have been displaced. In Jaffna 24.3% of those interviewed received the Samurdhi assistance and 53.3% were on the other state welfare schemes. In Batticaloa, 44.9% received Samurdhi assistance and 14.1% received other government welfare assistance. In Mannar 2.2% received Samurdhi assistance and 24.7% were on other government assistance schemes.

In terms of education, 23% of the total sample had schooling between Grades 1-5 while 18% had schooling between Grades 6-8. Thus, 51% did not have schooling beyond Grade 8. This could be a significant factor in the high levels of early marriages and early pregnancies noted in this research. For example, in the Polonnaruwa sample, 53.6% of women had schooling between Grades 1–8; correspondingly, 54.3% of the sample had married between the ages 15-18 years, indicating a possible link between school drop-out and early marriage. The proportion of women in the different districts who had completed schooling up to Grade 9-10 was 30%.

Early marriage

The study found that 31% of the sample had got married between the ages of 15 and 18 years, whereas the national age at marriage for women is 25 years. Focus group discussions in all six districts showed the relatively widespread phenomenon of early marriage. The primary reasons given, reportedly supported by parents, were poverty, lack of education and the lack of economic and social security.

Early marriage in the Ampara (50.8%) and Puttalam (35.7%) district samples may also have been due to the fact that in Muslim communities there is no legally regulated minimum age of marriage, except if a Muslim girl below the age of 12 is to be married, when permission has to be sought from the Qazi court. Conflict-induced displacement into Puttalam and the intensification of inter-ethnic tension and war in Ampara over the years could be contributory factors. Families also worried about the vulnerability of their young daughters when protective social networks and systems broke down, due to conflict and displacement; in such situations marriage was viewed as a means of “protecting the honour of the girl”.

Young people in Batticaloa and the border villages of Polonnaruwa were increasingly marginalised, often arrested, recruited into the military, the home guard, the LTTE or break-away militant factions of the LTTE. In the focus group discussions and case studies, respondents also said that families resorted to marriage of children as a means of protecting them from recruitment.

Early pregnancy

Another aspect that this research highlighted was that 33.0%, 46.2% and 34.0% of women in the Ampara, Polonnaruwa and Puttalam samples respectively, had had their first child between the ages of 15 and 18 years. In Polonnaruwa, a high 85% of the sample had had their first child by the age of 22, while this proportion was 58.8% in Ampara and 63.5% in Puttlam. The Ministry of Health reflected these concerns, noting that of the pregnant mothers under the care of the Public Health Midwives, the proportion of teenage pregnancies was high (9% or more) in six districts of the country; among them were Ampara, Batticaloa, Puttalam and Jaffna,Citation14Citation15 where our study took place. Alongside early marriage and under-age pregnancy, which increase health risks for young mothers, there was also evidence that young wives were being abandoned when they became pregnant or after the birth of several children.

Miscarriage

The number of respondents who reported spontaneous miscarriages was 23% in Jaffna, 24% in Ampara, 16.6% in Puttalam and 14.7% in Polonnaruwa. No national data were available for comparative purposes, and the women would not have known what led to their miscarriages. However, it is likely that at least some were related to poor reproductive health care or lack of access to care, as well as stress and malnutrition during the years of conflict and of restricted mobility. Repeated pregnancies, shifts in gendered responsibilities, which increased the work burden of women, are likely to have been additional factors.

Home births and traditional midwives

“During the conflict we were displaced from Ottamawadi and came to the camp for the displaced at Aliameen School in Senapura. I came of age at the camp and was there for 12 years. I was married while in the camp at 16 to a man from Senapura and stayed there. He is a home guard. Following my mother’s return from the Middle East, where she had gone to work as a housemaid, my family went back to Ottamawadi. I have had four children, now aged 11, 9, 6 and 4. All of them were born at home. I didn’t use any contraceptive method before but now I get injections because the children are small.” (RB, Polonnaruwa case study)

Government health care institutions are the primary location of childbirth in Sri Lanka. At the national level, home deliveries are estimated at 4.0% of live births. However, the figure for the North and East in 2003 was 19.4%, with Batticaloa and Mannar recording 31.4% and 38.4%, respectively.Citation16

Among our survey respondents, 15.8% of home births were reported in the six districts. Damaged health facilities located in the vicinity of their homes, distance to hospitals, conflict-induced danger and risks, lack of public transportation, poverty and cultural practices were cited as primary reasons. Poor households often could not meet the requirements for hospital confinement such as money for travel and the specified number of clean clothes required for the stay in hospital and other costs, and hence women had home births.

With the placement of a 4,700-strong cadre of trained public health midwives within the government health sector over the last 40 years, traditional midwives were no longer permitted to work. However, vacancies in the cadre of Public Health Midwives were noted in seven districts of Sri Lanka, including Jaffna and Batticaloa.Citation16 In the absence of or limited access to formal institutional health cadre in these areas, traditional midwives usually assisted in home deliveries.

“The traditional medicine woman is known as ‘Marauthuvivhvhi’. When a home birth is to take place she attends it. She cuts the umbilical cord, cleans the child and if there are abortions she treats them.” (Ms ALBM, 37 years old, Puttalam case study)

“Traditional midwives still play a role in helping childbirth at home. These rural physicians help mothers recover from the after-effects of childbirth. They give powders, herbs and oils. Elderly women engage in producing these medications. They give Perunkayam (a herbal drink) to drink and also prescribe water in which fennel seed is boiled.” (Ms R, 48 years old, Batticaloa case study)

The study showed that in these circumstances women not only actively sought the assistance of traditional midwives but appreciated their reproductive health services.

Conflict, reproductive health and violence

In displaced and conflict settings, the vulnerabilities of women increased and were further exacerbated by prevailing cultural norms and practices. The lack of employment opportunities for young men in displaced settings also led to conflict and violence within the home.

Domestic violence

“My elder daughter was married at 16. Her husband left her when she was 17 and she had one child. She was married again to a man with a first wife and she is very unhappy. My second daughter left her husband within a year of her marriage because he sold all her jewellery and wasted the dowry we gave her. My third daughter eloped and was later married. All my daughters were tortured by their husbands and their families, mainly for not bringing enough dowry. They were verbally abused and beaten. Their husbands are without jobs. My sons did not allow their sisters to acquire any skills and so they are unable to be self-sufficient.” (Muslim woman, 48 year old, Puttalam case study)

In the Ampara district, 49% of our respondents reported having being subjected to violence in the home, along with 67.8% of women in Puttalam, 30.5% in Polonnaruwa, 28.9% in Batticaloa, 20.1% in Jaffna and 14.7% in Mannar district. The most common perpetrator was the husband; fathers, brothers and mothers were also sometimes mentioned as perpetrators. The first incident of spousal abuse usually occurred within the first three years of marriage. Domestic violence was not a one-off incident but was repeated.

Muslim women spoke about how within Islam (as practised in Muslim communities in this study) sex education was banned, increasing the vulnerability of young girls. Cases of divorce were handled through the Qazi courts. Interviewees spoke about the experiences of women who have gone through these courts.

“Kaasi usawi (Qazi Court) is always very partial. Women are never represented in the Jury which is dominated by men. In cases of divorce, the woman is severely insulted; the judges are very rude towards the woman. There should be women representatives in the courts so that there is justice for women.” (Focus group discussion, Puttalam)

Issues such as these are important since they impact on women’s ability to access services pertaining to their health and well-being, whether provided by the State or religious bodies.

In the focus group discussions, women mentioned dowry as a common cause of domestic violence. There were also close links mentioned between domestic violence, sexual relations and contraception use. In the focus groups there was frank discussion about the experiences of women in their communities.

“Sometimes the husband would stop his wife from using contraception, thinking that if she uses contraceptives she will have extra-marital relationships. Then women have to use contraceptives secretly. However if the husband finds out she is doing this he would punish her with violence, accusing her of infidelity. This is a widespread situation among displaced communities.” (Focus group discussion, Mannar)

Structural factors sometimes excluded women in marginalised communities from access to legal redress in instances of domestic violence. For example, most police officers are from the majority ethnic group, Sinhala and are not fluent in Tamil, the language of the communities in most of the conflict areas.

Forced sexual intercourse in marriage

In Sri Lanka, forced sexual intercourse in marriage is not criminalised in law. Such practices, however, prevail. Women spoke of forced sexual intercourse with their husbands, of being compelled to consume alcohol or drugs or being subject to physical violence by their husbands before having sex. Due to the lack of privacy where the whole family had to share one room, women would try to refuse to have sexual intercourse with their husbands. However, as one woman said in a focus group discussion:

“Sometimes men have forced sex with women in front of their own children. This has made sexual intercourse very unpleasant for women.” (Focus group discussion, Mannar)

“I got married in 1992. My marriage was arranged by my parents… He started beating me on the very day of the marriage. He burns me with various things. He would tie my hands and my legs and have sex with me. He would forcibly have sex with me even during my periods. He wants me to agree whenever he wants to have sex.” (PV, 31 years old, Jaffna case study)

Conclusions

This article highlights some of the reproductive health concerns of Sri Lankan women living in a situation of conflict, many of whom are recipients of state welfare benefits and most of whom are engaged in low-paying, often intermittent occupations, mainly in the informal sector. In situations of displacement, women are often compelled to search for work in an unfamiliar environment. What we learned is that many women in these six districts were subject to violence in the home.

Despite high levels of literacy and school attendance at the national level in Sri Lanka, access to continuing education for many girls and women living in conflict situations has been poor. We noted the association between school drop-out rates and early marriage and pregnancy. Economic, social and physical insecurity are key to this phenomenon. Cultural practices together with parental anxiety about the vulnerability of their young daughters, due to conflict and displacement, were also push factors for early marriage of daughters.

Weakened health infrastructure and a lack of providers and access to hospital delivery care, combined with irregular access to work and income, made childbirth in situations of conflict high risk, forcing many women to deliver at home and to depend on traditional midwives, who are not formally authorised to undertake any reproductive responsibilities because they were supposed to have been replaced by trained midwives.

Physically and psychologically, women were at high risk of sexual and physical violence as a result of the breakdown of social networks, the use of alcohol and drugs by partners and the erosion of self-authority in their war-affected communities. Problems with dowry were also identified as key factors that led to violence. Marital rape is not criminalised in Sri Lanka, yet many women were being forced to have sex with their spouses and were denied the right to use contraception and to live free of coercion even within their own homes. This is exacerbated by the situation of conflict and displacement.

This research contributes to bringing out the voices of women, whose lives have been overshadowed by conflict and displacement, on the nature of structural barriers that impede their right to health care services, to making informed decisions about their lives and to live free from familial violence and control. It reiterates the urgent need to integrate women’s experiences into the reproductive rights discourse and into interventions for strengthening reproductive health care and enhancing women’s rights in Sri Lanka, especially in conflict-affected areas.

Notes

* The SIHRN was set up as part of the peace negotiations that followed the signing on the 2002 Ceasefire Agreement between the Government of Sri Lanka and the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE).

† The eastern boundary of Polonnaruwa adjoins the eastern conflict-affected areas. The research included the villages along this boundary, referred to as border villages.

References

- Ministry of Health. Implementing the ICPD Programme of Action: Sri Lanka 1994–2004. 2004; Population Division: Colombo.

- ATPL Abeykoon. Developments in the population and reproductive health field in Sri Lanka: the post-Cairo scenario. South Asian Women: Global Perspectives and National Trends in the 1990s. 2000; CENWOR: Colombo.

- Family Planning Association. Golden Jubilee Symposium Report, 2003.

- Department of Census and Statistics. Selected Millenium Development Goal (MDG) Indicators. Colombo, 2005.

- Department of Census and Statistics. Colombo, 2005.

- World Bank. Sri Lanka Poverty Assessment. Engendering Growth with Equity: Opportunities and Challenges. 2007; Poverty and Economic Management Sector Unit, South Asia Region: Colombo.

- National Committee on Women; UNIFEM. Gender and the Tsunami: Survey Report on Tsunami-Affected Households. Colombo, 2005.

- Centre for Women’s Research. Gender Dimensions of the Millenium Development Goals in Sri Lanka. Colombo, 2007.

- World Health Organization. Health System and Health Needs of the North and East of Sri Lanka. August 2002.

- Asian Development Bank; United Nations; World Bank. Sri Lanka: Assessment of Needs in the Conflict Affected Areas (SIHRN). Districts of Jaffna, Kilinochchi, Mullaitivu, Mannar, Vavuniya, Trincomalee, Batticaloa and Ampara. Colombo, May 2003.

- M Mukhopadhyay, N Singh. Gender Justice, Citizenship and Development. 2007; Zubaan and IDRC: Delhi/Ottawa.

- S Kottegoda. Assessment of Gender: Country Population Assessment. 2006; UNFPA: Colombo.

- F Zackeriya, N Shanmugaratnam. Stepping Out: Women Surviving amidst Displacement and Deprivation. 2002; Muslim Women’s Research and Action Forum: Colombo.

- Ministry of Healthcare and Nutrition. Annual Report on Family Health Sri Lanka 2004–2005. Colombo, 2007. p.7.

- Women and Media Collective. Study on outreach capacity of public health midwives in addressing the issue of domestic violence at the level of the community: insights from two districts in Sri Lanka. 2002. (Mimeo)

- Ministry of Healthcare and Nutrition. Medium-Term Plan on Family Health 2007–2011. 2007; Family Health Bureau: Colombo, 22.