Abstract

This paper summarises the findings of a study on second trimester abortion in England and Wales in 2005. Second trimester abortions constitute a relatively small proportion of the total number of legal abortions performed in these countries yet attract quite substantial public, and particularly media, attention. Discussion of these abortions has, however, been conducted within a context of little understanding of the factors which explain why they happen. This paper starts with a brief introduction to the policy context for provision of second trimester abortion, and a summary of existing research in the area. It then presents the results of a survey of 883 women on their own reasons why they had abortions in the second trimester. The key concept is that of “delay” and reasons for delay in seeking or obtaining abortion at five stages in the pathway to abortion. No clear, single reason emerges. Amongst the main reasons identified are uncertainty about what to do if they were pregnant, not realising they were pregnant, experiencing bleeding which may have been confused with continuing to have periods, and changes in personal circumstances. The paper ends with a consideration of the implications of the results for education, policy development and service provision.

Résumé

Cet article résume les conclusions d'une étude sur l'avortement du deuxième trimestre en Angleterre et au Pays de Galles en 2005. Les avortements du deuxième trimestre représentent une proportion relativement modeste du nombre total d'avortements légaux pratiqués dans ces pays, mais ils attirent beaucoup l'attention du public et en particulier des médias. Le débat sur ces avortements s'est néanmoins déroulé dans un contexte où les facteurs qui les expliquent sont mal compris. L'article commence par une brève présentation du contexte politique pour la pratique de l'avortement du deuxième trimestre, et un résumé de la recherche dans ce domaine. Il expose ensuite les résultats d'une enquête ayant demandé à 883 femmes leurs raisons pour avoir avorté au deuxième trimestre. Le concept clé est celui de « retard » et des raisons du retard de la demande et de l'obtention de l'avortement à cinq étapes de la voie vers l'avortement. Aucune raison claire et unique n'est apparue. Parmi les principales raisons identifiées, figurent l'incertitude sur la conduite à tenir en cas de grossesse, le fait que les femmes ignoraient qu'elles étaient enceintes, des pertes de sang leur ayant fait croire qu'elles continuaient à avoir leurs règles, et des changements dans leur situation personnelle. L'article s'achève en examinant les conséquences des résultats pour l'éducation, la définition des politiques et la prestation des services.

Resumen

En este artículo se resumen los resultados de un estudio sobre el aborto en el segundo trimestre, realizado en Inglaterra y Gales, en 2005. Los abortos de segundo trimestre constituyen una proporción relativamente pequeña del número total de abortos legales efectuados en estos países; sin embargo, atraen considerable atención pública, particularmente de los medios de comunicación. No obstante, el debate sobre estos abortos ha transcurrido en un contexto de poco entendimiento de los factores que explican por qué ocurren. Este artículo comienza con una introducción concisa al contexto de políticas para la prestación de servicios de aborto en el segundo trimestre, y un resumen de las investigaciones realizadas al respecto. Después, se presentan los resultados de una encuesta entre 883 mujeres sobre sus propios motivos para tener abortos en el segundo trimestre. El concepto clave es el de “demora” y las razones para aplazar la búsqueda u obtención de servicios de aborto en cinco etapas en la ruta hacia el aborto. No surge ninguna razón clara y única. Las principales razones mencionadas fueron: incertidumbre sobre qué hacer si estaban embarazadas, no darse cuenta de que estaban embarazadas, experimentar sangrado, que pudo haber sido confundido con continuar teniendo la regla, y cambios en circunstancias personales. Para concluir, se analizan las implicaciones de los resultados para la educación, la formulación de políticas y la prestación de servicios.

Second trimester abortions constitute a relatively small proportion of the total number of legal abortions performed in England and Wales; the great majority of abortions, almost 90%, are carried out during the first 12 weeks of pregnancy, while approximately 8.6% take place between 13 and 19 weeks and only 1.4% after 19 weeks of pregnancy. Since 2000, the proportion of all abortions that occur during the second trimester has remained roughly constant, but there has been a shift towards more of the first trimester procedures being carried out at under ten weeks' gestation.Citation1

Second trimester abortions, and especially those carried out towards the end of the second trimester, have attracted quite substantial public attention. Much of this has focussed upon the terms under which abortion is legally provided. There has been a great deal of recent media debate about “late abortion”,Footnote* in which demands have been made that the legal upper time limit for abortion in Britain be reduced.Citation2 In the first half of 2008, a set of changes to the laws that regulate the use of human embryos in research and treatment (primarily fertility treatment) will be tabled and debated. The most of important of these laws, the 1990 Human Fertilisation and Embryology Act, includes a section (Section 37) which sets out the upper time limit for abortion.

In specifying an upper time limit for abortion, the 1990 Human Fertilisation and Embryology Act modified existing abortion law in important ways. Prior to 1990, there was no upper time limit explicitly stated in the abortion law. Rather, when abortion was made legal in Britain through the 1967 Abortion Act, an upper limit of 28 weeks was assumed by reference to a 1929 statute, the Infant Life Preservation Act. This Act introduced into British law an offence of child destruction, through its first section, which prohibits the destruction of a child “capable of being born alive”, excepting only the case where such destruction was carried out in order to preserve the life of the woman. It is important to note that the 1929 Act was not passed to deal with abortion, but rather to deal with the killing of a fetus/baby in the process of being born. However, the rebuttable presumption it included, that the capacity of life was obtained at 28 weeks, was also read into the abortion law of the time, and later into the 1967 Abortion Act.Citation3

Between 1967 and 1990, the upper limit became more and more a source of debate, within and without the British Parliament. Bills put forward by Parliamentary opponents of legal abortion sought to reduce the upper limit. Medical opinion, however, also came to suggest that a new, lower upper limit should be introduced into the law, on the grounds that the gestation at which a fetus/baby was viable had shifted, and after a protracted and heated debate the abortion law was amended in 1990. The reformed law allows for abortion on the following grounds:

| (a) | that the pregnancy has not exceeded its twenty-fourth week and that the continuance of the pregnancy would involve risk, greater than if the pregnancy were terminated, of injury to the physical or mental health of the pregnant woman or any existing children of her family; or | ||||

| (b) | that the termination is necessary to prevent grave permanent injury to the physical or mental health of the pregnant woman; or | ||||

| (c) | that the continuance of the pregnancy would involve risk to the life of the pregnant woman, greater than if the pregnancy were terminated; or | ||||

| (d) | that there is substantial risk that if the child were born it would suffer from such physical or mental abnormalities as to be seriously handicapped. | ||||

Abortion is legal after 24 weeks only on grounds (b), (c) and (d).Citation2

Although discussion of the law is not the focus of this paper, it is worth noting that recent public debate has tended to focus almost exclusively upon the “ethical” issues associated with “late abortion”. This issue has been addressed primarily through claims and counter-claims as to whether medical care now allows babies born at less than 24 weeks' gestation to survive, with some people strongly pressing the case that survival rates have improved. This, they argue, makes abortion late in the second trimester unethical. Preferred upper limits of 16, 18, 20 and 22 weeks have all been proposed. This debate, to date, has thus been centred around the fortunes of babies born “too early”. as the starting point for discussion of reforming the abortion law.

In 2007, the UK Parliament's Science and Technology Committee carried out an enquiry considering scientific developments relating to the 1967 Abortion Act. Its terms of reference included consideration of “the scientific and medical evidence relating to the 24-week upper time limit on most legal abortions, including developments, both in the UK and internationally since 1990, in medical interventions and examination techniques that may inform definitions of fetal viability”. It recommended, on the basis of the medical and scientific evidence provided to it, that no change be made to the current upper limit for legal abortion.Citation4

The needs of prematurely born babies and their parents undoubtedly merit attention. Yet the notion that discussion of the abortion law might take place without proper consideration of the circumstances of women who seek to terminate their pregnancies (an entirely different group of women to those who deliver premature babies) appears, at the very least, unbalanced. The debate has also been unbalanced in that discussion of the ethics of restricting access to abortion has been almost entirely absent. So, too, has discussion of the practical questions of how to improve abortion and related services for women.

In this light, research-based understanding of the factors which explain why second trimester abortions happen in England and Wales could play a useful role in informing public discussion.Footnote* Notably little research attention has to date been paid to explaining why a minority of abortion-seeking women present at 13 weeks and over and what, if anything, might enable them to terminate their pregnancies at earlier gestations. The study described here, carried out in 2005 in England and Wales, sought to address this research gap and thereby contribute to a more informed public discussion about second trimester abortion.

Policy context: British abortion law

The British legal framework is unusual compared to others in countries where abortion has been legalised. The vast majority of European countries, for example, allow for abortion on request at least in the first trimester.Citation5 In contrast, under British law, at every stage of pregnancy abortion is only legal where two medical practitioners agree that the woman meets one of the four criteria reported above. The vast majority of abortions in Britain, over 90%, are performed on the ground that continuing the pregnancy poses a greater risk to the woman's physical or mental health, taking her social circumstances into account, than if the pregnancy were terminated.Citation6 In practical terms, the interpretation of this ground by medical practitioners makes abortion relatively accessible to British women. The fact that the woman's social circumstances can be taken into account makes this so, together with the development of a mainstream view in the medical profession that “health” should be defined broadly, and that abortion is always less of a risk to the woman's health than delivery.Citation7Citation8 However, access to legal abortion is contingent on medical assessment, meaning no “right to decide” is recognised in British law.

In addition, compared to most other abortion statutes, other aspects of the British abortion law appear more liberal. This is because of its relatively high upper time limit. Laws regulating abortion after the first trimester vary greatly in Europe, but only a small number permit abortion for a wide range of indications in the second trimester and, in particular, throughout the whole 13–24 week gestation band. Yet, under British law, second trimester abortion per se is currently treated no differently in law to first trimester abortion.

However, although there is no legal difference between first and second trimester abortions, access is more difficult in practice at later gestations.Citation9 Fewer doctors are prepared to carry out second trimester procedures, sometimes leading to longer travel times and expense for women since they need to find providers further from home.

It is not possible to ascertain how many British women who seek abortion during the second trimester are actually denied abortion on the basis that they do not meet the legal criteria. The British Pregnancy Advisory Service (bpas) has reported, however, that about 100 women each year request abortions from them when they are over 24 weeks gestation, and these requests have to be denied. It seems that a small number of British women do travel to other European countries in order to access second trimester abortion, with a very small number seeking post-24 week terminations outside Britain. For example, in 2003, 14 British women were treated by clinics in Spain that provide abortions at advanced gestation stages.Citation10

There are, to date, no published studies that provide comparative analyses of what happens in countries where access to second trimester abortion is more restricted by law than in Britain. What evidence there is does suggest, however, that under such legal regimes demand for second trimester abortion does not simply go away.

Experience in countries where efforts have been made to make abortion more accessible at early gestations does, it is claimed, point to success in shifting the pattern of demand strongly in favour of early abortion (Personal correspondence, Dr Christian Fiala, Gynmed Ambulatorium, Vienna). Women may, however, also live with a context of “unmet need” for second trimester procedures, and end up continuing pregnancies they would have terminated had the legal context been different (Personal correspondence, Stanley Henshaw, Alan Guttmacher Institute, New York). Some European women also travel to obtain abortion in countries where second trimester abortion is available to them legally. Women from Germany, Belgium and Luxembourg travel to the Netherlands, for example. British statistics contain evidence of such “abortion tourism”; in 2006, almost 7,500 non-resident women obtained abortions from British abortion providers, with over 1,300 of these during the second trimester. Most of these women travelled from the Republic of Ireland (where abortion is illegal) and Northern Ireland but lower numbers travelled from Italy, Malta, France and elsewhere (although some may be temporary residents).Citation1

The British law has remained unchanged for 40 years, other than the 1990 amendment to the upper time limit, which was the subject of a thorough debate amongst stakeholders and Parliamentarians at the time. Policy, however, has developed in important ways over the past decade. Abortion provision in Britain has been mainstreamed through its inclusion in the broader framework for the provision of sexual and reproductive health services by the National Health Service (NHS).Citation11 National disparities in proportions of abortions funded and provided by the NHS in different parts of the country have been recognised as a policy concern, and measures have been taken to attempt to address these.Citation11 Current policy also places emphasis on the importance of providing abortion as early as possible. Waiting time for abortion has emerged as a central concern for the Government's National Strategy for Sexual Health and HIV,Citation11 which draws on recommendations from the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG).Citation8,13 Some attention has been paid to encouraging innovation in the early abortion service, especially in regard to increasing the proportion of medical abortions in early pregnancy, since this may also assist in increasing the proportion of very early abortions. The statistical trend noted above – of a shift in the pattern of first trimester abortions towards the early first trimester – reflects these developments.

Second trimester abortion has been the subject of less policy attention. Appropriate medical regimens are set out in the RCOG guidelines, supported by the Department of Health, which state that no woman seeking abortion who meets relevant legal criteria should have to wait more than three weeks from first referral to abortion procedure.Citation12Citation13 Abortion at 20–24 weeks of pregnancy has become a specific policy concern, however. In response to the media debate on this issue, the Chief Medical Officer stated, in 2005, that local providers of health care should ensure that services are available to meet the needs of women seeking abortion up to 24 weeks' gestation. A number of further recommendations were also included regarding abortions occurring between 20 and 23 weeks' gestation. These include the development of a best practice protocol, commissioning of a review by the Department of Health of access to abortion services including support and counselling for women, that service providers review staff training needs, that staff involved in commissioning services are familiarised with the abortion law, and that Primary Care Trusts should identify sources of delay to make sure all abortions are carried out as early as possible in line with agreed performance indicators.Citation10

Previous research on second trimester abortion in England and Wales

There is a limited literature about why women seek second trimester abortion, their experience of doing so and the quality of the services they receive. For England and Wales, there are only two relevant published studies.

A 1996 paper by George and Randall reported on a retrospective analysis of the records of all the 111 women who had an appointment during the first year of a second trimester Unplanned Pregnancy Counselling Clinic in Portsmouth, England.Citation14 This study found that the common experience was of late presentation for abortion; most of the women requesting second trimester abortions did not present until a relatively advanced gestational stage. Only 13% of them could have been managed earlier through service improvements. Most cases in the study were thus designated “unpreventable”. Reasons for second trimester presentation varied, and included concealed teenage pregnancies, perimenopausal women, women with irregular menstrual cycles who did not associate amenorrhoea with pregnancy, and pregnancies that were initially wanted.

Another study of abortion at 19–24 weeks by Marie Stopes International (MSI) in their English clinics was published in 2005; 26 women were interviewed face to face and 84 questionnaires were completed.Citation15 The varied nature of the women's reasons for second trimester abortion emerged and for “most”Footnote* women there were a combination of factors. The “majority” reported they did not recognise the signs and symptoms of pregnancy until an advanced stage, thereby making late abortion “an inevitability rather than a conscious choice”. A “small minority”, who were aware they were pregnant at an early stage, either denied this was the case or decided the pregnancy was unwanted only later on as a result of changes in their circumstances. “Many” found the decision to terminate difficult and reported that it took them time to decide to proceed with it. MSI suggests women who undergo later abortion, compared with those who terminate earlier, tend to find the decision hard to make from the outset. “Some” reported quite lengthy delays in accessing services although, given that most did not realise they were pregnant until relatively late, the effect was primarily to shift the abortion further into the second trimester. One conclusion from these two studies is that, while accessibility of abortion services plays a part, it is only one part of the explanation for second trimester abortion.

This albeit limited existing work provided the following issues that formed the starting point for the study reported here:

the characteristics of women who terminate in the second trimester;

the range of reported reasons for delays in seeking/having procedures;

the relative frequencies with which different factors were reported to account for later presentation for abortion, with a focus on the balance between personal issues and service-related issues;

any particular issues that arose amongst women presenting at various times during the second trimester (with emphasis on 18 weeks and over);

the extent to which the above issues co-vary with age and other demographic characteristics.

Methodology

The research was carried out in 2005. The primary research instrument used was a questionnaire which asked women to report reasons why they had an abortion in the second trimester. The pathway to abortion was grouped according to five stages in the process: suspecting pregnancy, confirming pregnancy with a test, deciding to have an abortion, asking for an abortion and obtaining an abortion. Women were asked to report any reasons for delay at one or more of these stages, using provided responses (the questionnaire included a total of 39 specific reasons from which respondents could select those that they felt had applied to their own situation). Spaces were also left for women to add any additional comments. Women were also asked to indicate the lengths of time between each stage. This enabled the contribution of specific reasons for delay at different stages to be ascertained.

The questionnaire was developed through a process of literature review and through interviewing 16 staff working in clinics that carried out second trimester abortions, including doctors, counsellors, nurses and clinic managers, in order to gain their insights into reasons for second trimester abortions. It was also sent for comment to specialists in the field and piloted. The questionnaire was then made available in ten clinics in England; these comprised eight British Pregnancy Advisory Service (independent, non-profit) clinics and two private clinics. Resource constraints did not permit a wider sample site selection, so efforts were focussed on clinics that carried out a high volume of second trimester procedures. Between them, the selected clinics carried out around 41% of the almost 20,000 second trimester abortions to England and Wales residents in 2005, in most cases under contract to the National Health Service.

All women who underwent a procedure at 13 or more weeks were invited to complete the questionnaire, either during a waiting period in the clinic or after they had left. Stamped addressed envelopes were distributed to ensure anonymity of the responses; these were either posted back in bundles by the clinics (for those that were completed at the clinics) or returned direct to the research team. After removal of a very small number that contained inconsistent responses, usable questionnaires were returned by 883 women. The nature of the distribution of the questionnaires, and the large number of clinics involved, made accurate calculation of response rates difficult. Data were entered into and analysed using SPSS for Windows (version 14).

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the School of Psychology, University of Southampton, as well as the British Pregnancy Advisory Service and private clinics' own ethics committees.

Characteristics of the sample and data analysis

Ninety-four per cent of respondents' abortions were funded by the NHS, ranging from 100% for the under-16s to 91% for those aged over 30 years. Nationally, 91% of second trimester abortions were funded by the NHS in 2005, of which 87% were performed in independent (non-NHS) clinics. Compared with the overall national picture (obtained from data for 2005 for England and Wales for abortions carried out in non-NHS facilities), this sample contained relatively fewer 20–34 year olds (54% against 60% nationally) and a relatively higher proportion of under-20 year olds (38% against 30% nationally). The sample also contained a relatively higher proportion of women undergoing procedures at the later end of the range, with 17% at 21 weeks or over (as opposed to 8% nationally), 26% between 18 and 20 weeks (19% nationally), and 35% in the 13–15 week range (as against 54% nationally).

These variations are not surprising in the light of the sampling strategy adopted (to focus on the clinics with greater numbers of later procedures). In order to make the analysis more nationally representative the data were weighted to ensure, first, that the number of respondents by clinic matched the distribution of second trimester abortions by clinic and, second, that the distribution of respondents by gestation matched the national picture for the services included in the survey.

Analysis of the questionnaires returned showed up some ambiguities in the data, especially regarding reported times between the different stages. For example, the time between asking for an abortion and obtaining one, or between asking for an appointment with a doctor and actually seeing one, are likely to be reasonably accurate (although subject to recall bias). The time at which “suspecting pregnancy” occurred is rather more complex. A woman who experiences some forms of failed contraception, for example, may suspect pregnancy immediately after the sexual event; on the other hand, if contraception was used effectively (as far as she knew) she may only start to suspect pregnancy after disrupted menstruation, or after symptoms start to appear or as a result of some other trigger. To further complicate the issue, gestation lengths are calculated from the first day of the menstrual period prior to the conception occurring – which means that the total times reported by the women in terms of the five stages will not match the gestation lengths provided by the clinicians since they are using different time frames.

Each questionnaire was scrutinised in order to produce times that were as accurate as possible in the light of the reasons reported by the participants. In cases where one time was missing or inappropriate (n=151), the average time given by other respondents with similar reported reasons for delay was used. Generally, a cautious approach was adopted to arriving at the times reported. In order to address the dilemma of not knowing when the conception actually occurred, the time to suspecting pregnancy has been taken from the first day of gestation as calculated by clinicians. It essentially represents the gestation at which the pregnancy was suspected, whereas the “true” time to suspecting pregnancy would be shorter. Having adopted this approach to the data generated, the authors are confident that the findings reported below are reliable.

Findings

Reasons for second trimester abortion

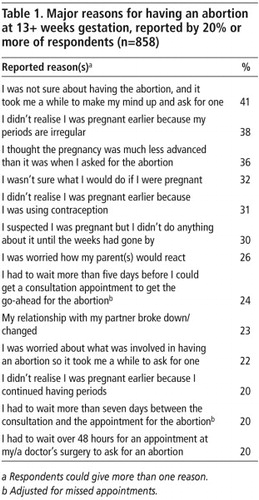

This study confirms the general findings of previous research summarised above that there is no single, dominant reason why women have abortions in the second trimester. Indeed, respondents reported a whole variety of reasons. In answer to the question Why would you say that your abortion has taken place at 13 or more weeks of pregnancy rather than earlier on in your pregnancy?, 13 different reasons were selected by at least one-fifth of respondents overall (Table 1).

The majority of women (85%) reported several factors that contributed to delay in having their abortion; for example, not realising they were pregnant until relatively late on in the pregnancy, then struggling with the decision to have an abortion and then having to wait to obtain the abortion.

The five stages of delay

The specific reasons reported were categorised into five stages of delay in the pathway from first suspicion of pregnancy to abortion. The proportion of women who reported at least one reason for delay during each of these five stages were as follows:

suspecting pregnancy (71%),

confirming pregnancy with a test (64%),

deciding to have an abortion (79%),

first asking for an abortion (28%), and

obtaining an abortion (60%).

Women's reports indicate that much of the delay occurred prior to requesting an abortion. Half of the women were at 13+ weeks' gestation by the time they first asked for an abortion. The median reported times, together with the inter-quartile ranges in parentheses, for each stage were as follows:

time to suspecting pregnancy 52.5 (21–79) days

time between suspecting and taking test 14.0 (2–24) days

time between test and decision 7.0 (0–21) days

time between decision and requesting abortion 2.0 (0–7) days

time between requesting and procedure 14.0 (7–21) days

• Delay in suspecting pregnancy

Of the overall sample, 71% of respondents reported at least one reason for delay in suspecting pregnancy. Lack of early awareness of pregnancy is thus an important factor in women requesting second trimester abortions. Half of the sample were at over 52 days' gestation when they first suspected they were pregnant, whilst one-quarter were at over 79 days' gestation. The main reasons why they didn't realise they were pregnant earlier were:

because my periods are irregular (49%),

because I continued having periods (42%), and/or

because I was using contraception (29%).

• Delay in taking pregnancy test

Sixty-four per cent of respondents overall indicated at least one reason for delay between suspecting their pregnancy and confirming it with a test. The median reported time between suspecting pregnancy and taking a test was 14 days. Around a third of respondents took over 14 days.

The most commonly reported reason (reported by 45% of women) was that while they suspected they were pregnant they “didn't do anything about it until the weeks had gone by”. Other responses reported by a large proportion were that they were “not sure about what they would do if they were pregnant” (37%) and/or fears over the reaction of their parents (29%) and/or partners (18%).

Seventy-one per cent of women confirmed their pregnancy at home; these women were less likely to wait over 14 days to do this – as opposed to those who were tested at a doctor's surgery or clinic. Part of the delay amongst some of the latter group was due to their not wanting to see their regular doctor and having to spend time finding somewhere else to go for a pregnancy test.

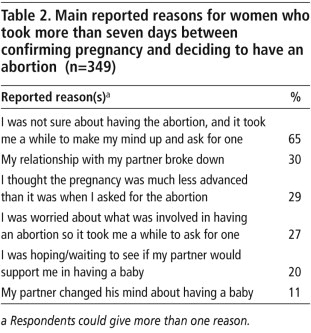

• Delay in deciding to have abortion

Seventy-nine per cent of respondents reported a delay in deciding to have an abortion. However, around half the respondents took one week or less between taking a test and then deciding to have an abortion. Among respondents who took more than one week, the reasons cited by more than 10% of them are shown in Table 2.

These data suggest that, in addition to some general indecision, responses of partners can form an important part of the context for women's decision-making processes. The choice to terminate a pregnancy, and the difficulties some experience making that choice, are bound up with women's relationships and the broader life context in which women struggle to make responsible choices about planning and founding families.

• Delay in first asking for abortion

One area where reported delays were noticeably short was in the time between deciding on abortion and first asking for one. For half the women, this took two days or less. Of those who took four days, 27% reported “I had to wait over 48 hours for an appointment at my/a doctor's surgery to ask for an abortion” and 13% that “I did not want to see my regular doctor to request an abortion, and it took time for me to find another doctor”. Overall, findings in this area appear to confirm the case made elsewhere that abortion decision-making for many women typically takes place outside of the influence of medical professionals. Professional assistance tends to be sought once a decision has been made.Citation9,16

• Delay in obtaining abortion

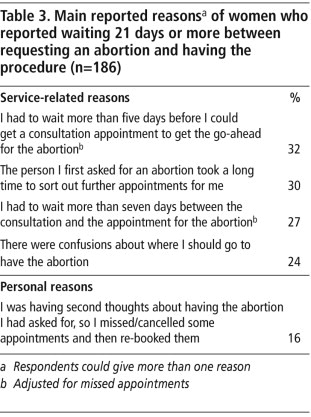

A relatively large proportion of the sample (60%) reported one or more reasons for delay between requesting an abortion and having the procedure. Forty-two per cent waited over two weeks between requesting and obtaining an abortion, whilst 23% waited over three weeks – beyond the minimum time period recommended by the RCOG. The reasons reported by 15% or more of them are shown in Table 3.

These data show that reasons for delay at this stage are not only service-related since, in part, delay for some is a product of continuing indecision; for example, having second thoughts, which led to missed appointments. For others, delay was caused by service-related factors, with a combination of delays in obtaining appointments with the abortion provider after referral and delays at the referral stage. These findings suggest a certain amount of confusion about the provision of abortion on the part of the first health professional approached. For 62% of the sample overall, this was their own doctor (general practitioner). However, first approaching their own doctor, as opposed to another health professional, was not statistically associated with lengthy delays.

Women aged under 18

It has sometimes been claimed that younger women are more likely to seek later abortions because of factors such as denial of pregnancy. Variations by age were not substantial in our sample; the median gestation was only one week longer for women under 18 than 18 and over. There were, however, some statistically significant differences in the reported reasons for delay according to age. For example, women under the age of 18 were more likely than women 18 and over to report delays at the early stages of the decision-making process for these reasons:

having a suspicion of pregnancy but not doing anything about it;

not being sure what to do if they were pregnant (leading to a delay in taking a pregnancy test); and

concern about what an abortion involved, so waiting a while to ask for one.

Women under 18 were also more likely to report delays because of concerns about how their parents would react. Like older women, however, indecision associated with partners' reactions was also significant, which confirms previous research about young women who opt for abortion.Citation9

Abortions towards the end of the second trimester

Because of recent public debate, we compared women in the sample who terminated pregnancies at 18 or more weeks with those who did so at 13–17 weeks. The abortions at 18 or more weeks' gestation were strongly associated with delays in the earlier stages of the abortion pathway. Women who had abortions at 18+ weeks took longer to suspect that they were pregnant and to confirm the pregnancy with a test, than did women who had abortions at 13–17 weeks. Half the women who had an abortion at 21+ weeks had been at least 18 weeks 2.5 days pregnant prior to taking a pregnancy test, compared with nine weeks' gestation for those who had abortions between 13–15 weeks. Women who had an abortion at 18+ weeks were also more likely to report having experienced continuing menstrual bleeding, which delayed the suspicion that they were pregnant.

Another important reason given by women who had had an abortion at 18+ weeks, as opposed to 13–17 weeks, was “The person I first asked made it hard for me to get further appointments”. At this stage of pregnancy, any delay related to the provision of services clearly carries the possibility of turning a second trimester abortion into a “very late” abortion.

Discussion

This study confirms the multi-dimensional nature of factors that account for second trimester abortion, and that factors relating to abortion service delivery provide only a limited part of the explanation as to why delays occur. It has, furthermore, identified the nature of delays that occur and where on the pathway to abortion most of the delay is distributed, including among women under age 18 and at earlier and later stages in the second trimester.

Overall, we found some clear service-related factors for delays. A reasonably large minority of women are waiting more than the recommended maximum time of three weeks from requesting to obtaining an abortion. However, the most important service-related factor leading to delay seemed to be confusion regarding abortion provision amongst doctors (most usually a general practitioner) referring women to a provider . This is a problem for all women seeking abortion, but especially for those whose pregnancies are already well advanced. Local referral pathways to the abortion service should thus be made clearer to all health and other professionals who may be involved.

Little evidence was found, however, to support the suggestion that the most important explanatory factor for second trimester abortion is a perceived difficulty in accessing services early in pregnancy. On the contrary, it is striking that most women in the study did not request an abortion until many weeks had gone by, and this was especially true for women who terminated pregnancies at 18 or more weeks. This study has found that, for all age groups and gestations, most reasons for delay are best considered “woman-related” – i.e. delays in suspecting and confirming the pregnancy and in deciding to have an abortion – rather than “service-related”.

This suggests, for England and Wales at least, limits on the extent to which policy changes directly related to early abortion services can be expected to reduce the proportion of second trimester abortions. This conclusion may come as a surprise; it has been a long-held assumption in the British abortion debate that making early abortion more accessible is the best way to reduce demand for second trimester procedures.

This finding also appears to contradict experience elsewhere; for example, it seems to contrast with that of the Netherlands, which has low rates of second trimester abortion provided in a context of very accessible early abortion and liberal abortion regulations overall. Research from the USA has, however, identified similar findings to those reported here, in particular delay caused by women not recognising or testing for pregnancy early on.Citation17Citation18

Our research certainly suggests that “woman-related” delays are worthy of a great deal more attention as they present challenges for education, service provision and policy development. In relation to the early stages of pregnancy, policy should seek to promote a greater awareness of the signs and symptoms of pregnancy, including the fact that some women do report experiencing continued menstrual bleeding while pregnant, as well as encouraging early pregnancy testing. This could reduce some of the delays related to recognition of pregnancy and relatively late initial contact with health services.

Abortion decision-making presents a particular challenge, but there are two areas that warrant consideration. First, some women reported “worry” about having an abortion, which contributed to their delay in making the decision. A better understanding, particularly amongst GPs (the first person with whom a woman is likely to discuss her abortion), of how abortion works and the safety of the procedure could assuage some of these concerns. Second, a greater opportunity to consider attitudes to, and the realities of, abortion in a non-crisis situation (during school-based sex and relationships education, for example) could bring some calmness into the area. This applies to young men as well as young women, so that the former are much more aware of the issues involved and can offer suitable support as and when needed.

The reported fear amongst some young people of the possible reactions from their parents is more challenging to deal with. In our previous research on pregnancy choicesCitation9 we observed a pattern whereby parents would often respond negatively to first hearing of their daughter's pregnancy, but such negativity did not often last for very long. Much depends on the local cultural attitudes towards early (and single mother) child-rearing, the openness of communication between parents and their children on sexual matters, the parents' aspirations for their daughter and other factors. In the longer term, greater attention to pregnancy outcome-related issues in schools' sex and relationships programmes, together with more open communication between schools and parents on what is covered, could help to alleviate some of these dilemmas.

Conclusions that may be drawn from our findings, in relation to the current public debate about the abortion law in Britain, are first that, all other factors being equal, a reduced upper time limit for abortion would have important consequences that policymakers need to appreciate. Our evidence shows that such a change will not bring about a reduced need for second trimester abortion. Rather, there is likely to be an increase in “abortion tourism”, i.e. British women travelling to other countries for these terminations. Moreover, there could be an increase in the number of women having no option but to continue pregnancies that are unwanted. Either of these outcomes would be a major step backwards in our efforts in Britain to fulfil government policy of keeping abortion safe and making it accessible.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all the clinic staff who facilitated the distribution of the questionnaires and all the women who completed them. The research was made possible by a grant from the Joseph Rowntree Foundation, and we thank the project manager and staff for their support. The full report of this study, with information on the statistical modelling conducted, can be found at the Centre for Sexual Health Research website at: <www.psychology.soton.ac.uk/modx/modx-0.9.5/assets/files/cshr/Late_Abortion_FINAL.pdf>.

Notes

* We have put the term “late abortion” in quote marks here to suggest that it mostly has particular, negative connotations, when used in the public abortion debate. It is notable that recently the term “late” has come to be applied to abortion at a widening variety of gestational stages, whereas in the past it was specifically used to describe abortion performed at a stage when the fetus would be viable. In the remainder of the paper, when discussing the data from the study we are reporting, we instead use “second trimester abortion”.

* Scotland was excluded from the sampling on the grounds that very few abortions take place there during the later stages of the second trimester. Most women seeking an abortion at 20+ weeks travel to independent sector clinics in England (there are no independent providers in Scotland).

* The descriptive terms “most”, “some”, etc. are reported as used in the original report.

References

- Statistical Bulletin. Abortion Statistics, England and Wales: 2006. 2007; Office for National Statistics and Department of Health: London.

- E Lee. The abortion debate today. K Horsey, H Biggs. Human Fertilisation and Embryology: Reproducing Regulation. 2006; Routledge: London, 231–250.

- S Sheldon. Beyond Control: Medical Power and Abortion Law. 1997; Pluto Press: London.

- House of Commons Science and Technology Committee. Scientific Developments Relating to the Abortion Act 1967, Twelfth report of session 2006-07, Volume 1 (HC 1045-1). September 2007.

- N Confalone. Abortion legislation in Europe. Choices. International Planned Parenthood European Network. 28(2): 2000; 2–7.

- Abortion Act 1967 (c.87) UK Statute Law Database. London: Ministry of Justice. At: <www.statutelaw.gov.uk/content.aspx?activeTextDocId=1181037. >. Accessed 4 January 2008.

- D Paintin. A medical view of abortion in the 1960s. E Lee. Abortion Law and Politics Today. 1998; Macmillan: Basingstoke, 12–19.

- Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. The Care of Women Requesting Induced Abortion. Evidence-based Clinic Guideline No. 7. 2004; RCOG Press: London.

- E Lee, S Clements, R Ingham. A Matter of Choice? Explaining National Variation in Teenage Abortion and Motherhood. 2004; York Publishing Services: York.

- Chief Medical Officer (CMO). An Investigation into the British Pregnancy Advisory Service (BPAS) Response to Requests for Late Abortions. 2005; Office of the CMO: London.

- Department of Health. National Strategy for Sexual Health and HIV. 2001; Department of Health: London.

- Government Response to the Health Select Committee's Third Report of Session 2002–03 on Sexual Health (Cmd 5959). 2003; Stationery Office: London.

- Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. The Care of Women Requesting Induced Abortion. 2000; RCOG Press: London.

- A George, S Randall. Late presentation for abortion. British Journal of Family Planning. 22: 1996; 12–15.

- Marie Stopes International. Late Abortion: A Research Study of Women Undergoing Abortion between 19 and 24 Weeks Gestation. 2005; MSI: London.

- U Kumar, P Baraitser, S Morton. Decision making and referral prior to abortion: a qualitative study of women's experiences. Journal of Family Planning and Reproductive Health Care. 30(1): 2004; 51–54.

- EA Drey, DG Foster, RA Jackson. Risk factors associated with presenting for abortion in the second trimester. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 107(1): 2006; 128–135.

- L Finer, LF Frohwirth, LA Dauphinee. Timing of steps and the reasons for delays in obtaining abortions in the United States. Contraception. 74: 2006; 334–344.