Abstract

In Mozambique, since 1985, induced abortion services up to 12 weeks of pregnancy are performed in the interest of protecting women's health. We asked whether any women were being adversely affected by the 12-week limit. A retrospective record review of all 1,734 pregnant women requesting termination of pregnancy in five public hospitals in Maputo in 2005–2006 revealed that it tended to be those who were younger and poorer, with lower levels of education, literacy and formal employment who were coming for abortions after 12 weeks. Countries such as Mozambique that endeavor to enhance equality, equity and social justice must consider the detrimental effect of narrow gestational limits on its most vulnerable citizens and include second trimester abortions. We believe the 12-week restriction works against efforts to reduce maternal deaths due to unsafe abortion in the country.

Résumé

Au Mozambique, depuis 1985, les avortements jusqu'à 12 semaines de grossesse sont pratiqués pour protéger la santé de la femme. Nous avons souhaité savoir si les femmes souffraient de la limite des 12 semaines. Un examen rétrospectif des dossiers des 1734 femmes enceintes ayant demandé une interruption de grossesse dans cinq hôpitaux publics de Maputo en 2005–2006 a révélé que c'étaient en général les femmes les plus jeunes et les plus pauvres, avec les plus faibles niveaux d'instruction, d'alphabétisme et d'emploi formel qui demandaient un avortement après 12 semaines. Des pays comme le Mozambique qui s'efforcent de promouvoir l'égalité, l'équité et la justice sociale doivent tenir compte des conséquences néfastes de ces limites étroites sur les citoyens les plus vulnérables et inclure les avortements du deuxième trimestre. Nous pensons que la restriction des 12 semaines va à l'encontre des activités pour réduire les décès maternels dus à l'avortement non médicalisé dans le pays.

Resumen

En Mozambique, desde 1985, los servicios de aborto inducido hasta las 12 semanas de embarazo, son efectuados con el fin de proteger la salud de las mujeres. Preguntamos si algunas mujeres estaban siendo afectadas adversamente por el límite de 12 semanas. Una revisión retrospectiva de los registros de 1,734 mujeres embarazadas, que solicitaron una interrupción del embarazo en cinco hospitales públicos de Maputo, en 2005–2006, reveló que casi siempre eran las mujeres más jóvenes y más pobres, con los niveles más bajos de escolaridad, alfabetismo y empleo oficial, quienes llegaban para que se les practicara un aborto después de 12 semanas. En países como Mozambique, que se esfuerzan por mejorar la igualdad, equidad y justicia social, se debe tomar en cuenta el efecto perjudicial de los límites gestacionales en sus ciudadanos más vulnerables y establecer servicios de aborto en el segundo trimestre. La restricción de 12 semanas va en contra de los esfuerzos por disminuir las tasas de muertes maternas atribuibles al aborto inseguro.

As many governments around the world begin to see the public health value in expanding safe abortion care to women in the first trimester of pregnancy, the possibility of reducing deaths from unsafe abortion and saving lives increases dramatically. However, in celebrating these changes, we must not neglect core issues of equality and justice. We must ask who is still denied when services are limited to the first 12 weeks of pregnancy.

Mozambique has taken bold steps to reduce pregnancy-related mortality through training and empowerment of mid-level providers, expanding access to essential obstetric care and contraception, and to HIV and malaria prevention and treatment.Citation1–3 Despite impressive declines in recent years, however, maternal mortality in Mozambique remains among the highest.Citation3–6 Abortion-related deaths are a major cause of preventable mortality, particularly among adolescents, representing 11–18% of all hospital-based maternal deaths.Citation7Citation8 Ethnographic research among traditional practitioners found that pregnancy termination continues to be among the most common requests for care.Citation9 Case fatality rates for abortion complications presenting at Maputo general hospital are 3%, three times the UN maximum recommended level of 1%.Citation7

Technically, abortion is permissible in Mozambique only in the event that the pregnancy threatens the life of the woman. However, in recognition of the magnitude of deaths from unsafe abortion experienced by women of reproductive age, the ways that pregnancy may complicate care and management of infectious diseases such as HIV, malaria and tuberculosis, and the high prevalence of sexual violence, a policy has been in place since 1985 that aims to overcome the legal impasse to provision of safe abortion care. Under that policy, induced abortion services for certain pregnancies up to 12 weeks have been authorised by the Ministry of Health in public hospitals, and hospital directors have the discretion to authorise pregnancy termination on an as-needed basis. Roughly 3,000 women's requests for an abortion were being approved annually in 2004.Citation10Citation11 Pre-requisites vary by institution but may include a request letter, photo identification, a photo of the male partner, and until 2007 a cash payment averaging US$ 24 (range nil to US$ 100). However, the average cost of unsafe abortion continues to be lower.Citation11Citation12 Given a per capita annual income of only US $340 in 2006, the cost of safe abortion places it out of the reach of many women in Mozambique.Citation13 Historically, women getting a safe abortion have tended to be older, urban and with higher income.Citation13Citation14 They were more likely to be married, employed, light-skinned, with a history of contraceptive use, and completed secondary education than those presenting with complications of unsafe abortion.Citation15

Methods

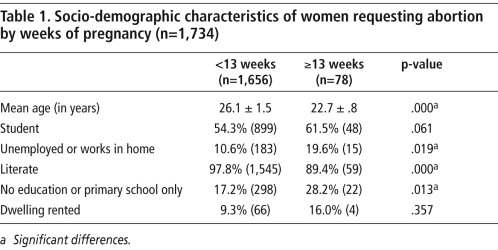

To understand who is excluded by the 12-week gestational limit, we re-analysed data from a study eligibility screening tool administered to all women presenting for termination of pregnancy between April 2005 and November 2006 in the five public hospitals in Maputo, as part of a clinical study of alternatives to ultrasound for misoprostol abortion up to 11 weeks. We compared the socio-demographic characteristics of 78 women (4.3%) who presented with pregnancies ≥13 weeks (excluded from the study) with 1,656 women who presented at less than 13 weeks. To test for significant differences (Table 1) at the p=.05 level, t-tests were conducted for continuous variables and x 2 for dichotomous variables.

Results

Table 1 shows that those who presented for termination at or above 13 weeks of pregnancy represented a small proportion of those seeking safe abortion in the five public sector hospitals overall (4.3%). However, the women needing second trimester services were more likely to be younger and with lower levels of education, literacy and formal employment. They were probably also more likely to live in rented dwellings, a sign of limited resources in the family, and to still be in school.

Discussion

Our findings concur with other studies that have shown that younger, poorer and less educated women often present later in pregnancy for many reproductive health services, including antenatal, delivery and emergency obstetric care.Citation16 Adolescents may be physiologically pre-disposed to present later for both antenatal care and abortion because irregular menses can make identifying pregnancy early difficult,Citation17 and due to fear of the social consequences.

From this exploratory secondary analysis of screening data, we conclude that policies that limit safe termination of pregnancy to women presenting in the first trimester may discriminate against younger women and those with fewer educational and financial assets, disproportionately affecting young women, and potentially contributing to precocious motherhood or unsafe abortion, with their well-documented health and social risks.

In countries such as Mozambique, where safe abortion services incurred a fee until recently, poorer women were more likely to arrive later in pregnancy because of the efforts needed to amass sufficient funds. Even though fees are now no longer charged, other reasons for presenting after 12 weeks and being denied a safe abortion may relegate the country's most vulnerable citizens to risk their lives with unsafe services. A country such as Mozambique that is dedicated to enhancing social justice and promoting the health and well-being of all its citizens regardless of age and income must carefully consider the detrimental effects of narrow gestational limits on safe abortion provision. We believe that expanding the 12-week restriction would help to maximise Mozambique's many efforts to reduce maternal morbidity and mortality.

References

- Libombo A, Ustá MB. Mozambique abortion situation: country report. Paper presented at Expanding Access: Mid-level Providers in Menstrual Regulation and Elective Abortion Care. South Africa. 2–6 December 2001.

- A Cumbi, C Pereira, R Malalane. Major surgery delegation to mid-level health practitioners in Mozambique: health professionals' perceptions. Human Resources for Health. 5: 2007; 27.

- C Santos, D Diante, A Baptista. Improving emergency obstetric care in Mozambique: the Story of Sofala. International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics. 94: 2006; 190–201.

- L Jamisse, F Songane, A Libombo. Reducing maternal mortality in Mozambique: challenges, failures, successes, and lessons learned. International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics. 85: 2004; 203–212.

- K Hill, T Kevin, C AbouZahr. Estimates of maternal mortality worldwide between 1990 and 2005: an assessment of available data. Lancet. 370: 2007; 1311–1319.

- C Menéndez, C Romagosa, MR Ismail. An autopsy study of maternal mortality in Mozambique: the contribution of infectious diseases. PLoS Medicine. 5(2): 2008; e44.

- F Machungo, G Zanconato, S Bergström. Reproductive characteristics and post-abortion health consequences in women undergoing illegal and legal abortion in Maputo. Social Science and Medicine. 45(11): 1997; 1607–1613.

- ACL Granja, F Machungo, A Gomes. Adolescent maternal morbidity in Mozambique. Journal of Adolescent Health. 28: 2001; 303–306.

- R Chapman. Endangering safe motherhood in Mozambique: prenatal care as pregnancy risk. Social Science and Medicine. 57: 2003; 355–374.

- Machungo F. O aborto inseguro em Maputo. Paper presented at Unsafe Abortion Conference, Maputo, 24–26 April 2004.

- F Machungo, G Zanacanoto, S Bergström. Socioeconomic background, individual cost, and hospital care expenditure in cases of illegal abortion in Maputo. Health and Social Care in the Community. 5(2): 1997; 71–76.

- Bugalho AMA. Perfil Epidemiológico, Complicações e Custo do Aborto Clandestino. Comparação com aborto hospitalar e parto em Maputo, Moçambique, 1995.Vol. I. Tese apresentada à Faculade de Ciências Médicas da Universidade Estadual de Campinas, São Paulo.

- World Bank 2006 Gross National Income ATLAS Method. Available from: <http://siteresources.worldbank.org/DATASTATISTICS/Resources/GNIPC.pdf. >. Accessed 11 December 2007.

- E Hardy, A Faúndes, A Bugalho. Comparison of women having clandestine and hospital abortions: Maputo, Mozambique. Reproductive Health Matters. 5(9): 1997; 108–115.

- V Agadjanian. “Quasi-legal” abortion services in a sub-Saharan setting: users' profile and motivations. International Family Planning Perspectives. 24(3): 1998; 111–116.

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística. Inquérito Demográfico e de Saúde, 2003. Ministério da Saúde, Maputo, Mozambique.

- AA Olukoya, A Kaya, BJ Ferguson. Unsafe abortion in adolescents. International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics. 1(75): 2001; 137–147.