Abstract

This paper describes experiences and lessons learned about how to establish safe second trimester abortion services in low-resource settings in the public health sector in three countries: Nepal, Viet Nam and South Africa. The key steps involved include securing the necessary approvals, selecting abortion methods, organising facilities, obtaining necessary equipment and supplies, training staff, setting up and managing services, and ensuring quality. It may take a number of months to gain the necessary approvals to introduce or expand second trimester services. Advocacy efforts are often required to raise awareness among key governmental and health system stakeholders. Providers and their teams require thorough training, including values clarification; monitoring and support following training prevents burn-out and ensures quality of care. This paper shows that good quality second trimester abortion services are achievable in even the most low-resource settings. Ultimately, improvements in second trimester abortion services will help to reduce abortion-related morbidity and mortality.

Résumé

Cet article décrit les expériences et les enseignements obtenus sur la création de services sûrs d'avortement du deuxième trimestre en situation de ressources limitées dans le secteur de la santé publique de trois pays : Népal, Viet Nam et Afrique du Sud. Les étapes clés étaient l'obtention des autorisations, la sélection des méthodes d'avortement, l'organisation des centres, l'acquisition des équipements et fournitures nécessaires, la formation du personnel, la mise en place et la gestion des services et la garantie de qualité. Plusieurs mois sont parfois nécessaires pour obtenir l'autorisation d'introduire ou d'élargir les services d'avortement du deuxième trimestre. Des activités de plaidoyer sont souvent requises pour sensibiliser les acteurs clés de l'administration et du système de santé. Les prestataires et leurs équipes exigent une formation approfondie, notamment une clarification des valeurs ; après la formation, un suivi et un soutien préviennent l'épuisement professionnel et garantissent la qualité des soins. L'article montre que des services de bonne qualité d'avortement au deuxième trimestre sont possibles même dans les environnements aux ressources les plus limitées. En fin de compte, les améliorations dans ces services aideront à réduire la morbidité et la mortalité liées à l'avortement.

Resumen

En este artículo se describen las experiencias y lecciones aprendidas sobre cómo establecer servicios seguros de aborto en el segundo trimestre, en lugares con escasos recursos, en el sector salud pública de tres países: Nepal, Vietnam y Sudáfrica. Los pasos fundamentales son: obtener la autorización necesaria, seleccionar los métodos de aborto, organizar los establecimientos de salud, obtener el equipo y los suministros necesarios, capacitar al personal, establecer y manejar los servicios y garantizar la calidad. Posiblemente tome varios meses obtener la autorización necesaria para lanzar o ampliar los servicios en el segundo trimestre. Por lo general, se necesitan esfuerzos de promoción y defensa para concientizar a las partes interesadas del gobierno y del sistema de salud. Los prestadores de servicios y su equipo necesitan capacitación completa, que incluya aclaración de valores; el monitoreo y apoyo post-capacitación ayudan a evitar agotamiento y garantizar la calidad de la atención. Es posible lograr servicios de alta calidad de aborto en el segundo trimestre, incluso en los lugares donde existe la mayor escasez de recursos. A la larga, las mejoras en los servicios de aborto en el segundo trimestre ayudarán a disminuir las tasas de morbilidad y mortalidad relacionadas con el aborto.

When provided by trained clinicians using sound practices, second trimester abortions are safe.Citation1 However, in the many settings where they are not provided safely, they contribute disproportionately to abortion-related morbidity and mortality.Citation2Citation3 The World Health Organization and others have promoted the availability of safe abortion in the second trimester, yet little has been published about how to establish safe services, particularly in developing countries where resources are limited.

Ipas, a US-based non-governmental organisation, has worked on abortion service delivery for more than 35 years in a wide variety of settings in Africa, Asia, Latin America and Eastern Europe. In Viet Nam, our work to strengthen public sector abortion care identified problems in second trimester abortion services resulting from outdated clinical techniques.Citation4 We provided technical assistance to the Vietnamese Ministry of Health to improve second trimester services, followed by similar assistance to the Family Health Division in Nepal and provincial reproductive health departments in South Africa.

This paper describes experiences and lessons learned in Nepal, and to a lesser extent Viet Nam and South Africa, and recommendations based on these experiences for delivering safe, effective second trimester abortions. Key steps include securing necessary approvals, identifying the need for the methods available, organising the facility, obtaining necessary equipment, preparing the health care team, managing the services, and ensuring high quality care.

Securing approval and selecting abortion methods

Nepal

Prerequisites to providing safe second trimester abortion services include educating policymakers and clinicians about grounds permitted in existing abortion laws, and obtaining the necessary government approval, which can take many months to complete.

In Nepal, advances in women's rights have enabled women to obtain legal abortion since 2002, on request through 12 weeks of pregnancy, in the case of rape or incest through 18 weeks, and at any time in pregnancy with the approval of a medical practitioner for fetal impairment or risk to the woman's life or physical or mental health. A guardian's consent must be obtained for women younger than 16.Citation5 To implement the law, the Nepal government established the Technical Committee for the Implementation of Comprehensive Abortion Care (TCIC) in 2003. The TCIC trained providers in comprehensive abortion care, but services were initially established primarily for first trimester abortions.

According to a national, facility-based study in 2006, 4,245 women (13% of those seeking abortion) were denied abortion services because they were more than 12 weeks pregnant.Citation6 Advocates and policymakers therefore began a dialogue aimed at introducing safe second trimester services in the public sector.Citation7Citation8 Consultative meetings with health professionals and programme managers resulted in a Strategic Plan on Second Trimester Abortion, which outlined standards and guidelines for clinical protocols and health facility requirements, and specified that only obstetrician–gynaecologists could provide second trimester abortions. The Plan includes both surgical and medical abortion as recommended by the World Health Organization: dilatation and evacuation (D&E) and medical abortion with mifepristone–misoprostol.

Before services could be implemented, it was necessary to obtain approval from the Ministry of Health and Population for the Strategic Plan. Advocacy efforts were directed at policymakers regarding the need for second trimester services, evidence-based clinical protocols and the Plan. As a result of these efforts, in April 2007 the Ministry endorsed the Plan.

First trimester medical abortion was only being used in research studies at the time (it has subsequently been approved for routine use), so approval had to be obtained from the Drug Department Administration, on the basis of global evidence of safe and acceptable regimens, particularly using data from India.

The TCIC's goal is to increase access in all regions by having at least one and, where possible, two second trimester methods available. The Family Health Division of the Ministry decided that both medical abortion and D&E should be offered at all tertiary care facilities, in a staged manner. This would allow women a choice of method, and because the caseload is high in these facilities, providers would be able to maintain their skills. TCIC and government colleagues felt strongly, however, that medical abortion was safer outside major urban areas and tertiary centres, where caseloads are smaller and providers may lack training and proficiency in D&E. The lower cost of medical abortion as compared to D&E also means that rural and lower-level sites are more likely to be able to offer it. Where medical abortion is the only choice, however, tertiary referral needs to be in place in cases where women want D&E and for back-up for failed medical abortion. At present, many providers remain unaware of these issues.

Viet Nam

In Viet Nam, although second trimester abortion has been legal since the 1960s and providers are aware of the law, the Kovacs method, an outdated technique, has remained in use.Citation4 To change this, a one-year, small introductory D&E study (n=100 women) was conducted at one hospital in 1999, after which D&E was added to the national abortion standards and guidelines. The guidelines, however, required a nearly two-year approval process involving national expert review meetings, dissemination of drafts to provincial health leaders, regional review meetings to incorporate feedback and finalise the drafts, and submission to the Ministry of Health for signature (Do Thi Hong Nga, Country Director, Ipas Viet Nam, personal communication, 25 April 2008) Unfortunately, the guidelines excluded second trimester medical abortion, despite its use at major hospitals, as some decision-makers had concerns about second trimester misoprostol use. The government is now considering authorising second trimester medical abortions nearly a decade after D&E was approved and many years after authorisation of first trimester medical abortion.

These experiences suggest some of the policy issues relevant to service delivery, which are usually within the influence of health policymakers, programme directors and senior service providers. National standards and guidelines should indicate which levels of the health care system and types of providers are permitted to do second trimester abortions, which methods are approved or need approval, and the allowable indications. Where these issues are vague or unspecified, Ministerial or other approval may be required. The availability of medicines and equipment may also require regulatory approval.

The characteristics of medical and surgical methods drive management decisions and influence choices about which to offer and how to set up and implement services. For example, a busy clinic that already provides first trimester aspiration abortions might more easily add 13–18 week D&E services, with referrals to an area hospital for complicated or later cases. Facilities offering medical abortion can use a small, private room on their obstetrics ward with a small number of reclining chairs or beds. A teaching hospital, such as Nepal's Maternity Hospital, might upgrade its abortion services and add both D&E and medical abortion, and provide training opportunities for district hospital providers. Medical abortion is likely to increase women's access to care in settings where emergency back-up skills, equipment or facilities are not in place to provide D&E or where infection prevention is a problem. D&E may be a better option in settings where mifepristone is too expensive or unavailable, where high caseloads limit the availability of beds for women having medical induction, or where overnight stays are not possible.

Assessing sites and organising facilities

Hospitals, clinics, and other types of facilities can all be safe and appropriate settings in which to provide second trimester abortions, with back-up from a tertiary setting for lower-level facilities. Conducting a facility needs-assessment can help determine what provision exists already, how existing resources might be re-arranged or managed differently, and what additional resources are needed. It is important to assess existing facilities and plan space for services before embarking on provider training.

In Viet Nam, a formal facility assessment was not required because of Ipas' longstanding technical assistance to their abortion and family planning programmes. This meant that second trimester D&E services could be introduced into hospitals without delay.

Nepal carried out a structured assessment and planning process. Six of the country's 19 tertiary hospitals were selected as possible sites, representing each of the country's five geographic regions. Requirements for selection included provision of standard first trimester abortion services; availability of basic supplies, equipment, space and personnel for both first and second trimester services; and status as a referral hospital. In December 2006, the TCIC conducted a two-day needs assessment at each of the six hospitals, and gauged their capacity and willingness to provide second trimester abortions. The assessments confirmed whether the sites met the selection criteria as well as criteria developed by Ipas.Citation9 Five of the six hospitals (covering 10% of the population) satisfied the prerequisites for both methods and an adequate recovery area. The sixth hospital did not offer first trimester services or have space for second trimester services, and providers were less willing to introduce them. However, the assessment laid the groundwork for training providers in the five qualifying facilities and helped achieve smooth delivery of services.

For both second trimester methods, facilities need to have a private counselling area, and a comfortable place for women to wait for 3–4 hours for cervical preparation to take effect. D&E requires a procedure or operating room, while medical abortion calls for a separate space (with reclining chairs, beds or cots) where women can labour and expel the pregnancy. Induction takes a mean of six hours to complete and may require overnight stay. Adequate space is needed for recovery and toilets, and conveniently located equipment and supplies.

Equipment and supplies

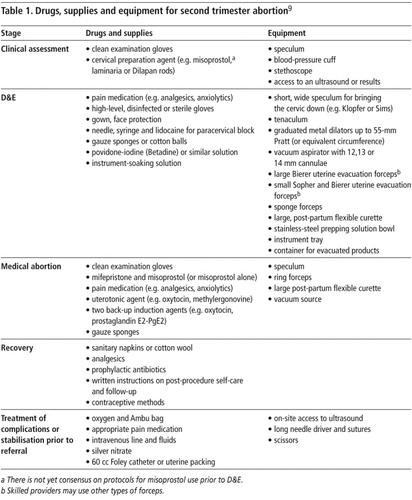

Equipment and supplies for first and second trimester medical abortion are similar, while agents for cervical softening and specialised instruments are needed for D&E (Table 1). For second trimester abortion we also recommend access to an ultrasound machine in case of questions about length of pregnancy or for assistance with D&E. In Viet Nam's Hanoi Obstetrics and Gynaecology Hospital, the ultrasound machine is located on a different floor but in the same wing as the abortion procedure rooms, and thus easily accessible.

Ensuring ongoing availability of instruments, medicines and supplies can be difficult in low-resource settings.Citation10 Ideally, they should be included on facility and government supply lists so that public facilities can use their allocated budgets to purchase them through local distributors. This has been the case in Nepal, where the maintenance of an ongoing supply chain has evolved since the initial needs assessment. Clinic managers were responsible for procuring items available in-country, while Ipas purchased D&E equipment from abroad. After the initial clinical training, the government contracted a local distributor to resupply sites within normal government supply-chain channels. TCIC staff helped build the capacity of government logistics personnel to incorporate second trimester supplies into the normal budgeting and procurement system.

In Viet Nam, a leading hospital sought to have a local medical supply company develop forceps similar to imported ones, which would have lowered production costs and eliminated import barriers. Unfortunately, this effort was unsuccessful. Although Vietnamese hospitals are currently still using their original D&E equipment, they will have to import equipment when needed.

In Nepal, funds from an international donor to the safe motherhood programme have been allocated for D&E equipment, although provider training in additional sites has not yet taken place. South Africa is allocating funds at the provincial health system level and purchasing equipment through local medical distributors. Careful planning with investments of this type can help prevent equipment shortfalls that might lead to delayed service start-up or cancelled services. To ensure continuity of second trimester abortion care, it is critical that sites systematically review routine and emergency supplies, ensure that instruments are sterile and drugs unexpired, and all materials and back-up instruments are available.

Training staff and setting up services

Providing high quality second trimester abortion services requires staff preparation, training and support. Provider willingness is a key component. Women deserve experienced, trained and supportive staff who are not judgmental or disparaging. Because many providers find second trimester abortion services challenging, staff support must start even before clinical training and continue when services are in place. In our experience, values clarification exercises can be particularly important during training and service start-up (see Turner et al in this issue).Citation11

In Viet Nam, Ipas initially introduced D&E clinical training without screening providers for their commitment to doing second trimester abortions. Participants were selected solely on the basis of their clinical expertise and position within the hospital. Although five physicians were trained, two never provided D&Es and one retired within a year. They gave only cursory answers when asked why, which eventually led to the admission that they were uncomfortable with second trimester services and felt that it was “bad for their karma”. Careful selection of whom to train and clarification of values and perspectives can help to avoid wasting valuable training of providers in the longer run.

In Nepal, TCIC and Ipas worked together to prepare staff for service delivery in the five sites. Learning from the experience in Viet Nam, programme planners conducted a two-day values clarification workshop in April 2007 for hospital managers, physicians, nurses and policymakers, before finalising the selection of participants for clinical training.Citation12Citation13 Participant surveys completed before the workshop revealed mostly neutral or negative attitudes towards second trimester abortion services. After the workshop, however, respondents were more likely to assert that women's circumstances and right to abortion outweighed their own biases. At the workshop's conclusion any physician or nurse assistant who still felt uncomfortable proceeding with training was allowed to opt out; none did so.

South Africa held a national consultative meeting with doctors identified as willing to provide second trimester services, to clarify values and address concerns about conscientious objection. Although it was not formally a values clarification workshop, all the providers who participated subsequently attended clinical training. Two trainees who were not at the consultative meeting were initially very uncomfortable with the clinical training by comparison (Ramatu Daroda, Senior Training and Services Advisor, Ipas, personal communication, 23 June 2008).

In our experience, a team approach is the best way to support women and provide safe second trimester abortion care. The health care team's roles should include:

counselling and providing information about the procedure, recovery and follow-up care, and contraceptive options

conducting an ultrasound – if needed

administering and monitoring pain medication

performing D&E or prescribing the medication

supporting the woman, and

monitoring recovery.

Some of these roles are interchangeable between physicians and nurses. In Nepal, nurses provide counselling, support during D&E, and monitoring during recovery; physicians perform the ultrasound and D&E. For medical abortion, advanced practice nurses may be trained to prescribe and monitor the medication. Use of non-physician providers can increase service accessibility and lower costs,Citation14 reserving the use of physicians for D&E itself, back-up procedures and more complex gynaecological needs.

Clinical training in Nepal for nine physicians and six nurse–midwives took place in June 2007 over the course of two weeks at the tertiary-level Kathmandu Maternity Hospital, which, as a model comprehensive abortion care site, has high patient volume, emergency back-up, skilled personnel, and adequate facilities for both medical abortion and D&E. Experienced international trainers used a competency-based approach to impart knowledge, clinical skills and confidence. Skills practice was largely focused on D&E, to take advantage of trainer supervision. Training methods included didactic sessions, case studies, role-plays, small group work, pelvic model practice using checklists, and hands-on training with patients. All learners had to be competent on the pelvic models before practising with women. The second week of the course was devoted solely to clinical practice with a trainer.

It is important that providers learning D&E are already highly skilled in first trimester surgical abortion. To maximise training time and minimise clinical risks, selecting clinicians with specific criteria is essential. In Nepal, all the doctors trained had been through the first trimester Comprehensive Abortion Care course and were experienced in doing a paracervical block and using MVA. In contrast, in South Africa first trimester MVA is mostly done by midwives, who are not currently allowed to manage second trimester procedures; therefore, many of the physicians trained in D&E were not proficient in MVA and had not done paracervical blocks. The needs assessment did not discover this before training commenced, so trainers had to add it to the course schedule unexpectedly.

Dating pregnancy correctly is also a crucial skill in providing safe abortion services, especially in the second trimester, as misdating can lead to complications. Trainers must give learners feedback on their ability to correctly date pregnancy. For example, after a second trimester abortion the fetus can be evaluated using biparietal diameter, foot size and/or femur-length measurements against the pre-abortion clinical assessment to determine the accuracy of dating. During the training in Nepal, providers using these checking methods found that they often over-estimated gestational age. While clinically conservative, this can result in women being turned away if they are considered too late for either first or second trimester abortion.

Based on experience in Viet Nam, Nepal and South Africa we recommend that clinical training should start with early second trimester cases, at 13–15 weeks, progressing to 16–18 weeks and beyond thereafter. This increases confidence and reduces risks. It can be difficult for providers to achieve competence if caseloads are limited. Subsequent coaching by an experienced provider can help improve skills and assist newly-trained clinicians to integrate services into their facilities. In South Africa, one trainer continued to coach learners at their home facilities for several months after the course ended to increase competence.

In Nepal, similarly, following the training course, TCIC staff worked with trainees to ensure they were fully prepared to start performing second trimester procedures – this included a whole-site orientation, which introduced the service and key steps for quality assurance to all medical staff as well as record-keepers, cleaners and guards. Discussions included instrument processing, drug purchase and interactions with patients. Staff members responsible for managing medications and record-keeping need to be acquainted with the new service insofar as it creates changes in their respective work area. This multi-faceted approach to preparing the health care team set the stage for launching services, and four of the five sites began providing services in July 2007. At the fifth site, the physician who had recently completed training was transferred to a clinic that was not equipped for second trimester abortions, and steps are underway to initiate services there.

A final consideration regarding the abortion team is the risk of burn-out with second trimester abortion. Terminating pregnancies with fully formed fetuses is often emotionally draining for staff despite their commitment to the women needing care.Citation15 Confirming completion of a 7–8 week abortion involves sorting through blood clots and tissue, while that of a second trimester abortion means examining fetal parts or an intact fetus. To support the team and reduce burn-out, managers in Nepal rotate staff responsibilities within the abortion service. This requires ensuring that enough people are available for this. This may sound impossible in some settings – but at a minimum, giving staff the opportunity to talk about their feelings and any stress they experience can help keep the team functioning well, benefiting both staff and women receiving care.

Managing services and ensuring quality

A range of management issues, including costs, scheduling and referral systems, quality assurance and monitoring, and disposal of fetal tissue, have emerged from Ipas' experience in the three countries.

The World Health Organization calls for “reducing fee differentials for abortions performed at different durations of pregnancy and among different methods, so that women can access services that best suit their needs without regard to cost”.Citation16 In Viet Nam, however, the government does not regulate patient fees and the cost of abortion varies widely between sites and methods used. In early 2008, MVA for first trimester abortion averaged around US$4–7 compared to about US$20–25 for medical abortion; D&E cost about US$80–100. In South Africa, abortion services in public facilities are free, regardless of gestational age or technique used.

The Nepal Strategic Plan specifies that the cost of second trimester services to women should be no different than the cost of first trimester abortion. When a woman is not able to afford even that fee, facilities commonly tap their own special funds for poor and vulnerable women. This policy achieves the WHO guidelines on abortion financing and has been consistently applied at all the sites currently providing services. Currently, the cost of a second trimester abortion in Nepal is 1,000 rupees (US$16) for D&E or medical induction. Ideally, health facilities will have parity of costs between various abortion methods and gestational ages, and build in a safety net for women who cannot afford the fees.

A system is needed for accepting referrals from primary care providers for second trimester abortions. Second trimester abortions can often be completed in one day if they are scheduled carefully. Scheduling of service provision can minimise women having to wait between cervical preparation and having a D&E, and with medical abortion, to maximise the number of women who complete the abortion without an overnight stay. The Maternity Hospital in Nepal schedules women having D&E to receive misoprostol for cervical preparation in the morning and the procedure in the afternoon, after which the woman is discharged. Many women prefer D&E as it requires only one day at the hospital. For inductions, however, after the clinical assessment, counselling and informed consent, women are given the mifepristone pill, asked to take it at home the following day at 6am, and come to the clinic at 9am for the misoprostol. This approach has increased the likelihood that the woman will expel the pregnancy during clinic hours and avoid having to be admitted overnight. This saves the facility and the woman money, although it does require two visits. Women who live far from the hospital often opt to take the mifepristone only when they arrive at the hospital, even if it means admission to the ward later, to avoid bleeding en route. Some women who come for induction decide to have a D&E once they are counselled about the differences. Thus far, there have been no instances of women taking mifepristone and not returning for misoprostol the next day.

In Viet Nam, some specific issues related to viewing and disposal of the fetus were identified. In central and southern Viet Nam, it is not uncommon for women to ask for the abortus at any gestational age for private burial. In Nepal, it is not customary to view or bury a fetus of less than 28 weeks. Facilities should have a policy regarding such requests that take into consideration tissue disposal regulations and infection prevention practices. In most cases the woman is not going to see the fetus and the provider should make sure that it is discreetly covered when removing the tray from the room. Some women, especially those who had a wanted pregnancy and had an abortion for fetal or maternal health indications, may wish to view the fetus after induction. This is not recommended after D&E, which should be made clear to the woman beforehand as the fetus is in pieces. Providers may want to examine the fetus for evidence of any abnormalities detected, in order to be able to discuss them with the woman.

A central management issue for any abortion service is that of complications. If emergency services, including laparoscopy or laparotomy are not available on site, there should be an efficient system for transferring patients to appropriate facilities. In Viet Nam, the sites offering D&E are national tertiary care centres as well as provincial hospitals that can manage most complications. There are also established referral links. The five sites in Nepal are all referral centres within their regions and equipped to manage complications; nevertheless, referral forms were created in the event a site needs them, and can be used by lower-level facilities once second trimester services are expanded. Complications management reporting forms should also be part of the record-keeping system.

It is imperative that abortion teams maintain skills, especially in settings where second trimester abortion is not a large part of the daily caseload. Regular emergency practice drills can help prepare staff in the event of a serious complication,Citation17 reduce stress if a complication does arise and increase competence and confidence in responding. There should also be periodic reviews of difficult cases, to identify what worked well and what could be improved.

Site-based quality improvement approaches have been helpful for monitoring and strengthening abortion services. Viet Nam uses the Performance Improvement ApproachCitation18 and has incorporated second trimester abortion into that system. The TCIC in Nepal has a trainee follow-up system that tracks and supports providers in developing their proficiency once they have returned to their workplace. This management system synergistically uses provider logbooks, facility records, supportive supervision, coaching visits and provider network meetings to help clinicians address quality assurance issues. Second trimester abortion services have now been incorporated into this system. Each trained provider receives, post-training, three-monthly follow-up visits from TCIC and the trainers. During the first day of the visit, a site assessment is carried out using a standardised checklist to examine the availability of drugs, equipment and supply inventory, waste disposal system, and observe abortion procedures; the second day the trainer and TCIC staff provide feedback and clinical coaching.

An important underpinning of services in Nepal is that second trimester abortion was added to the government health management information system's comprehensive abortion care indicators, forms, monitoring and supervision plans. This allows managers to track who is served, such as ethnic minorities and marginalised groups, as well as their location. Facility logbooks were updated to include information about D&E and medical abortion, complications and their management. The Drug Department Administration also set up a monitoring system in order to prevent medical abortion drugs being sold on the black market.

Record-keeping systems must maintain confidentiality and continuity of care for women returning for follow-up appointments, any complications, contraceptive or other services. In South Africa, Ipas is supporting ongoing coaching and monitoring but as services are established and expand, mechanisms need to be built into the health system to sustain the quality of care. We expect that this may be harder due to the decentralised manner in which provincial health departments work.

Recommendations

This paper outlines a practical framework for safe second trimester abortion service provision. The following summarises our recommendations for service delivery:

Ensure policy-level support for second trimester abortion, taking advantage of broader changes in abortion law and other health care legislation where possible.

Review and bring up to a high standard existing second trimester guidelines and services, including countries with liberal laws, and ensure regulatory approval of necessary medicines.

Offer both surgical (D&E) and medical second trimester abortion, depending on type of facility, provider skill, and the needs and preferences of women in the community. A choice of methods is ideal; one safe method is better than none.

Assess and equip sites before training providers, to ensure that sites are ready for services to start soon after training is completed.

Assess providers' skills and experience before training, to ensure that they meet prerequisites and that their training needs will be met.

Conduct a values clarification workshop before clinical training to help participants understand the issues around second trimester abortion and their own attitudes about providing care to women. Include managers, nurses and auxiliary staff as well.

Train providers using competency-based methods. For D&E training, start with 13–15 week abortions and then later abortions as learners gain competence and confidence. Plan for follow-up coaching after D&E training to improve skills and support teams in initiating services.

Schedule service provision to minimise women's waits and maximise the number of women who complete their abortion without an overnight stay (especially by starting medical abortions early in the day).

Accommodate the needs of women in the community, e.g. regarding disposal or burial of fetal tissue.

Ensure a robust system for referral for emergency obstetric care in case of complications.

Regularly monitor the quality of services as part of ongoing monitoring systems, using a facility-based quality assurance programme that includes review of logbooks, discussions among staff, feedback from women, and coaching of staff, in ways acceptable to staff. Where there are no existing quality assurance systems, second trimester abortion care can be a vehicle for launching a broader quality management programme.

Nepal, South Africa and Viet Nam will have many more lessons to share as they continue to expand their abortion services. We hope that their experiences will prompt discussion in the field and encourage those from other settings to share their experiences too.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Nepal Family Health Division; Nepal Technical Committee for the Implementation of Comprehensive Abortion Care, its staff, consultants and partner agencies; Vietnamese Ministry of Health, Reproductive Health Department; Ipas Viet Nam; South African Provincial Health Departments; Ipas South Africa; Do Thi Hong Nga; Ramatu Daroda; Laura Castleman; Elizabeth Garfunkel; Elese Stutts; Merrill Wolf; Ralph Hardy; and Claire Viadro.

References

- Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. The Care of Women Requesting Induced Abortion. Evidence-based clinical guideline No. 7. 2004; RCOG Press: London.

- Berer M. Why focus on second trimester abortions? Proceedings of International Conference on Second Trimester Abortion. 29–31 March 2007, London.

- Winikoff B. Second trimester abortion: a global overview. Proceedings of International Conference on Second Trimester Abortion. 29–31 March 2007, London.

- LD Castleman, TO Khuat, AG Hyman. Introduction of the dilation and evacuation procedure for second trimester abortion in Viet Nam using manual vacuum aspiration and buccal misoprostol. Contraception. 74(3): 2006; 272–276.

- Forum for Women, Law and Development. 2002. Reforms incorporated in the country code (eleventh amendment) law. At: <www.fwld.org.np/11amend.html. >. Accessed 24 June 2008.

- Government of Nepal Ministry of Health & Population, Department of Health Services, Family Health Division. National facility-based abortion study. 2006; Government of Nepal: Kathmandu.

- Forum for Women, Law and Development and Planned Parenthood Global Partners. Struggles to legalize abortion in Nepal and challenges ahead. 2003; FWLD: Kathmandu.

- C Bird. Family Health Division, Ministry of Health, His Majesty's Government of Nepal, CREHPA, FWLD, Ipas, PATH. Women's right to choose: partnerships for safe abortion in Nepal. 2005; FWLD: Kathmandu.

- TL Baird, LD Castleman, AG Hyman. Clinician's Guide for Second Trimester Abortion. 2nd ed., 2007; Ipas: Chapel Hill NC.

- M Abernathy. Planning for a Sustainable Supply of Manual Vacuum Aspiration Instruments: A Guide for Program Managers. 2nd ed., 2007; Ipas: Chapel Hill NC.

- KL Turner, AG Hyman, MC Gabriel. Clarifying values and transforming attitudes to improve access to second trimester abortion. Reproductive Health Matters. 16(31 Suppl): 2008; 108–116.

- KL Turner, K Chapman. Abortion attitude transformation: a values clarification toolkit for global audiences. 2008; Ipas: Chapel Hill NC. (Forthcoming).

- AG Hyman, A Sissine. Second trimester abortion values clarification pre- and post-workshop survey results. 2007; Ipas Nepal: Kathmandu. (Unpublished).

- Berer M. Provision of abortion by mid-level providers: international policy, practice and perspectives. Bulletin of WHO 2008. (In press).

- WM Hern, B Corrigan. What about us? Staff reactions to D&E. Advances in Planned Parenthood. 15(1): 1980; 3–8.

- World Health Organization. Safe Abortion: Technical and Policy Guidance for Health Systems. 2003; WHO: Geneva.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Committee opinion: medical emergency preparedness. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 108(6): 2006; 1597–1599.

- M Luoma, L Voltero. Performance improvement: stages, steps and tools. IntraHealth International/PRIME II Project 2002. At: <www.prime2.org/sst/index.html. >. Accessed 24 June 2008.