Abstract

In Argentina, the unequal distribution of the burden of cervical cancer is striking: the mortality rate of the province of Jujuy (15/100,000) is almost four times higher than that of the city of Buenos Aires (4/100,000). We aimed to establish the socio-demographic profile of women who were under-users of Pap smear screening, based on an analysis of a representative sample of Argentinean women from the First National Survey on Risk Factors in 2005. We found that in Argentina, women who are poor, unmarried, unemployed or inactive, with lower levels of education and reduced access to health care, and women over the age of 65, were under-users of screening. Screening must not remain opportunistic. Strategies must incorporate the needs and perceptions of socially disadvantaged women, and increase their access to screening. Of utmost importance is to provide good quality screening and treatment services that reach women who are at risk. Pilot projects using new, alternative technologies should be encouraged in less developed parts of the country. Promotion among health professionals of the scientific basis and effectiveness of each screening modality is essential to reduce wasteful practices such as annual screening and screening of young women that waste resources and fail to reduce cervical cancer incidence and mortality rates.

Résumé

En Argentine, la distribution inégale du cancer du col de l’utérus est frappante : le taux de mortalité dans la province de Jujuy (15/100000) est près de quatre fois supérieur à celui de la ville de Buenos Aires (4/100000). Nous souhaitions établir le profil sociodémographique des femmes sous-utilisatrices du dépistage par frottis, sur la base de l’analyse d’un échantillon représentatif d’Argentines tirée de la première enquête nationale des facteurs de risque en 2005. Nous avons constaté qu’en Argentine, les femmes pauvres, célibataires, chômeuses ou inactives, peu instruites et avec un accès réduit aux soins de santé ainsi que les femmes de plus de 65 ans étaient sous-utilisatrices du dépistage. Le dépistage ne saurait demeurer opportuniste. Des stratégies doivent intégrer les besoins et les perceptions des femmes socialement défavorisées, et élargir leur accès au dépistage. Il est particulièrement important d’assurer des services de dépistage et de traitement de bonne qualité qui atteignent les femmes à risque. Dans les régions moins développées du pays, il faut encourager des projets pilotes utilisant de nouvelles technologies. La promotion auprès des professionnels de la santé de la base scientifique et de l’efficacité de chaque modalité de dépistage est essentielle pour réduire les dépenses inutiles comme le dépistage annuel et le dépistage de jeunes femmes qui gaspillent des ressources et ne réduisent pas l’incidence de la maladie et son taux de mortalité.

Resumen

En Argentina, la distribución desigual de la carga del cáncer cervical es tremenda: la tasa de mortalidad en la provincia de Jujuy (15/100000) es casi cuatro veces más alta que la de la ciudad de Buenos Aires (4/100000). Nos propusimos establecer el perfil sociodemográfico de las mujeres que eran sub-usuarias del tamizaje por prueba de Papanicolaou, basándonos en un análisis de una muestra representativa de mujeres argentinas de la Primera Encuesta Nacional sobre Factores de Riesgo realizada en 2005. Encontramos que en Argentina, las mujeres pobres, solteras, desempleadas o inactivas, con niveles de escolaridad más bajos y menor acceso a los servicios de salud, y las mujeres mayores de 65 años de edad, eran sub-usuarias del tamizaje. Éste no debe continuar siendo oportunista. Las estrategias deben incorporar las necesidades y percepciones de las mujeres socialmente desfavorecidas y ampliar su acceso al tamizaje. Es imperativo proporcionar servicios de tamizaje y tratamiento de buena calidad que alcancen a las mujeres en riesgo. En las zonas menos desarrolladas del país, se deben promover proyectos pilotos que utilicen nuevas tecnologías alternativas. La promoción entre los profesionales de la salud de la base científica y la eficacia de cada modalidad de tamizaje es esencial para disminuir las prácticas poco costo-efectivas, como el tamizaje anual y el tamizaje de mujeres jóvenes, que desperdician recursos y no impactan en la incidencia y mortalidad del cáncer cervical.

Cervical cancer is a disease symbolic of health inequality; it is primarily a cancer of poor, socially vulnerable women, even though there are simple and relatively low cost means of preventing it. In Argentina, the unequal distribution of the burden of the disease is striking: the mortality rate of the province of Jujuy (15/100,000) is almost four times higher than the rate of the city of Buenos Aires (4/100,000). Within Jujuy, the area of Puna has a mortality rate of (25/100,000),Citation1 comparable to the highest mortality rates in the world.Citation2

A National Programme on Cervical Cancer Prevention was established in Argentina in 1998. Its recommendations include cytology-based (Pap smear) screening for women aged 35–64 every three years after two annual negative tests, in agreement with international scientific recommendations.Citation3 However, Argentina is a federal country and health management is decentralised; many provincial programmes recommend wider age ranges (e.g. starting at age 15–18 in seven provinces) and a higher frequency of screening (e.g. annually). In general, both at national and provincial level, cervical cancer prevention programmes have been introduced piecemeal, they lack quality control systems and information systems to monitor their actual impact.Citation1 As a result, mortality rates have not significantly decreased in the last 30 years.Citation4

A key step towards make a screening programme effective is achieving high coverage rates, as demonstrated in developed countries.Citation3 In Argentina, the First National Survey on Risk Factors in 2005 showed that 52% of women aged 18 and over reported having had a Pap smear in the previous two years.Citation5 This is much higher than the average for developing countries as a whole, which is 19%, ranging from 1% in Bangladesh to 73% in Brazil.Citation6 However, screening is mainly opportunistic in Argentina, which is associated with social inequality in both developed and developing countries.Citation3 Evidence from other countries shows that coverage tends to be unequally distributed where screening is opportunistic: older women, women with low socio-economic status and educational level, and women with reduced access to health care tend to have lower access to and uptake of screening.Citation7Citation8

The aim of this paper is to demonstrate the extent of this social inequality in Argentina so that national policymakers have the evidence to take action to reach women with little or no access to screening. We established the socio-demographic profile of women who are under-users of cervical screening from data in the First National Survey on Risk Factors. By identifying the factors that deter them from accessing screening, we devised outreach activities that will help to increase coverage among the women who need screening the most.

Materials and methods

We used data from the 2005 First National Survey on Risk Factors to identify variables that predict under-use of Pap smear screening. The survey was a cross-sectional, household interview survey, representative of the Argentinean urban population aged 18 and over living in cities with 5,000 or more inhabitants, conducted by the National Ministry of Health. It used an Urban Sampling Framework built by the National Institute of Statistics and Censuses. A detailed description of the survey methodology can be found elsewhere.Citation5Citation9 Households were selected using a multi-stage probability sampling design. In each household, the head was interviewed to collect information about the dwelling, and one adult was then randomly selected to answer the questionnaire. Only women answered questions regarding Pap smears.

The questionnaire covered basic socio-demographic and health status items, and specific questions on health risk factors. In the section “Preventive health measures” there were two items on use of Pap smear screening: “Have you ever had a Pap smear?” and “Have you had a Pap smear in the last two years?”. These questions were used to build two measures of Pap smear under-use: no smear in the last two years and never having had a smear. Although the National Programme recommends a Pap smear every three years, the survey questions were based on a two-year interval. As the frequency of screening ranged from one to three years in different provinces, and our aim was to determine a socio-demographic profile of under-users of screening, the two-year interval is not a methodological limitation.

Four categories of predictors were considered in the analysis: socio-demographic variables, use of preventive health services, access to health care and self-perceived health status. Socio-demographic variables were: age (18–34,35–64, 65+) to incorporate the potential effect of the National Programme recommendation on age interval (women aged 35–64); marital status (married/live together; unmarried: single/divorced/widow); head of household (yes; no); education level (tertiary; secondary; never gone to school/special education/primary); household size (1,2–5,6+); employment status (employed, unemployed, inactive). The variable “unsatisfied basic needs” (yes; no), was used as an indicator of poverty level. Respondents were classified according to residence in one of seven regions: city of Buenos Aires, 24 districts of Greater Buenos Aires, Pampeana, Northwest, Northeast, Cuyo, and Patagonia, as used by the National Institute of Statistics and Censuses.Citation5

Current use of contraceptive methods (yes; no) was used to measure use of preventative health services. Access to health care was measured through two variables: health coverage (yes: social security/private scheme; no: public health system); and saw a doctor in the last four weeks (yes; no: without health problem; no: with health problem. Self-perceived health status was grouped in two categories (good [excellent/very good/good]; bad [regular/bad]).

Data were analysed using Stata 8.0. We calculated frequencies of the two measures of screening under-use for levels of each potential predictor. Simple and multiple logistic regressions were used to evaluate the individual and the simultaneous impact of all predictors. Percentages, crude and adjusted odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals were calculated using SVYLOGIT, a user-defined statistical analysis system procedure that incorporates sampling weights and the characteristics of the complex sample design. The model used an entry criterion of p=0.05 and removal criterion of p=0.051 to calculated adjusted odds ratios. Variables that did not fulfill these criteria were removed from the model.

Findings and discussion

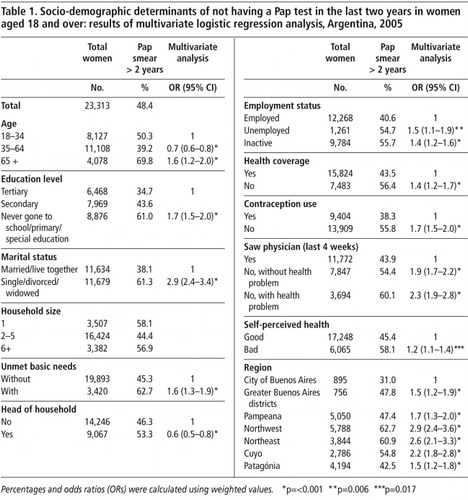

Table 1 shows results of the multivariate analysis of the association between not having a Pap smear in the last two years and predictor variables. After adjusting for all variables included in the model, the probability of not having a Pap smear in the last two years was higher among women who were older, had lower education levels, were poor, unemployed or inactive, had no health coverage or were not using contraceptive methods. Being unmarried was the most important predictor of not being screened in the previous two years. Single/divorced/widowed women were 2.9 times more likely not to have had a Pap smear in the previous two years compared to married women. Region of residence was also an important predictor of no screening in the last two years. Women who lived in the Northwest, Northeast and Cuyo regions were 2.8, 2.6 and 2.2 times more likely not to have had a Pap smear in the previous two years, respectively. In addition, women who had not seen a physician in the previous four weeks despite having a health problem, were 2.3 times more likely not to have been screened.

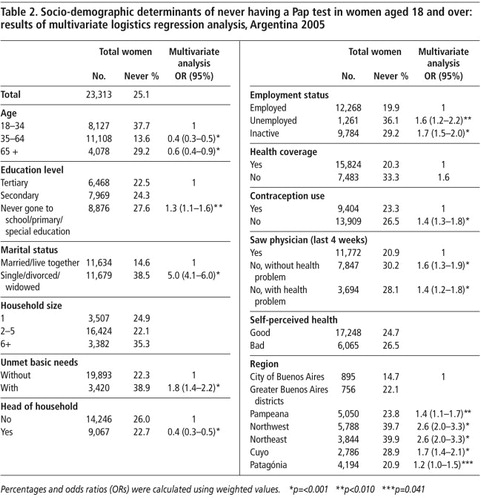

Table 2 shows the results of the multivariate analysis of the association between never having had a Pap test and predictor variables. After adjusting for the other independent variables the probability of never having had a Pap test was higher among younger women (under 35), and among women who were heads of household. The probability of never having been screened was also higher among women who had lower education levels, were poor, unemployed or inactive, had no health coverage, were not using contraceptive methods or had not seen a physician in the previous four weeks even if having a health problem. Being unmarried was the most important predictor of never having been screened. Unmarried women were five times more likely never to have had a Pap smear compared to married women. Region of residence was also an important predictor: women who lived in the Northwest, Northeast and Cuyo regions were 2.6, 2.6, and 1.7 times more likely never to have been screened, respectively.

The development in recent years of new screening and prevention technologies in addition to cytology (visual inspection, liquid-based cytology, HPV screening and HPV vaccine) has stimulated national and international initiativesCitation10Citation11 to encourage governments to take action against cervical cancer and spurred discussion of which are the most appropriate measures for each country. However, the cost of the HPV vaccinesCitation12 means that they cannot be implemented immediately in most developing countries. In any case, vaccines will not eliminate the need for screening programmes. Thus, Argentina is facing a two-fold challenge: to make a highly imperfect screening programme effective and increase Pap smear coverage rates as soon as possible, while planning for the introduction of an effective HPV vaccination programme in the longer term.

Even if new technologies are incorporated into the programme, whichever screening test is used, alone or in addition to cytology, health workers will still need to reach the under-users of screening. Insufficient coverage is related not only to the screening technique but also (and probably mainly) to women’s demographic and socio-economic situation and how preventive services are organised. It must be recognised that socially disadvantaged women do not utilise preventive services because of socio-economic barriers and other reasons for non-attendance.

In Argentina, the National Programme on Cervical Cancer Prevention includes recommendations to actively search for and invite target women for screening. However, this recommendation has never been translated into an efficient call-and-recall system; screening has remained mainly opportunistic. As in other countries,Citation7,8,13 in Argentina we found that it is women who are poor, unmarried, unemployed or inactive, with lower levels of education and reduced access to health care, who are under-users of Pap tests.

One of the strongest predictors of screening under-use was being unmarried, which is consistent with previous studies in both high and low-resource settings.Citation8,14 Unmarried women may receive less frequent obstetric and gynaecological care, with fewer chances of opportunistic cancer prevention advice.Citation8 Not having the potential emotional and social support provided by husbands and partners has also been given as a possible explanation for this difference.Citation15 It is important for unmarried women who have ever had sex to be informed that they should have Pap smears, even if they are not currently having sexual intercourse. They might not perceive themselves to be at risk or in need of screening.

Not having seen a doctor in the last four weeks, despite having a health problem, was also an important predictor of screening under-use. It implies that there are social, economic or geographic barriers to accessing health care, including preventive services. Several studies in other Latin American countries found that transportation costs and distance played a significant role in access to screening services. Rates were much higher where clinics were more accessible or where mobile clinics brought services to women.Citation16Citation17

In our study, women with no health insurance coverage, and those who were not using contraceptive methods, were also less likely to have been screened. This profile was basically the same whether the women had not been screened in the previous two years or had never been screened. These associations have been reported in a number of other studies as well.Citation8,15,18,19 The fact that women with no health insurance were more likely to have lower uptake of Pap screening might be linked to deficiencies in service infrastructure in some public health centres in Argentina, where screening for uninsured women should be provided. Studies that have analysed other barriers to Pap smear screening showed that waiting times, availability of counselling and arrangements to assure maximum privacy during the examination are important determinants of women’s uptake of Pap tests.Citation16Citation17 Thus, assuring the availability of women-centred, high quality services is essential to high coverage.

Women with lower education levels were less likely to be screened, a finding that is consistent with previous reports.Citation15Citation20 Education level is usually considered a surrogate for socio-economic level,Citation21 but it also influences screening through knowledge, awareness and extent of social inclusion.Citation22 In our study, education was an independent predictor of screening even after controlling for socio-economic level. Evidence shows that education raises awareness of the importance of regular health check-ups and hence the willingness to do so; it may also improve understanding of information, extent of communication with the health practitioner and interpretation of results.Citation22 Bradley et al have pointed out that in settings where health-seeking behaviour is guided by traditional notions of ill-health, women may not be sure whether modern medicine can heal them.Citation23 It is important to note that the regions in Argentina with lower Pap smear coverage are those with a higher proportion of indigenous people who, compared to the general population, have lower education levels.Citation24 Cultural perceptions about ill-health may also contribute to the association between low levels of education and reduced coverage. The fact that an important proportion of the indigenous population consider that the use of traditional healing practices should be officially recognisedCitation24 supports this hypothesis. Thus, increasing screening rates is not only a question of providing factual information, but of devising messages and communication strategies that are understood locally, incorporating cultural perceptions of preventive cancer care.Citation17

Compared to women aged 35–64, women aged 18–34 were less likely to have been screened in the previous two years or at all. The National Programme recommends screening every three years only for women aged 35–64, which could partially explain the lower uptake in this age group. However, most provinces do not follow the national recommendation on age range; many of them recommend starting Pap tests at younger ages (e.g. age 15–18 in seven provinces) and more frequently (i.e. annually). In addition, even in provinces that do follow national recommendations, there is limited adherence on the part of health professionals (e.g. gynaecologists) to recommendations. We have observed in conversations with heads of gynaecological and cervical pathology services all over the country that a great many of them consider that women must begin screening when they begin sexual intercourse, regardless of age. Therefore, other factors may be responsible for the lower coverage among younger women. Age at sexual initiation might be an alternative explanation, as the age group 18–34 probably has a higher proportion of women not sexually initiated, especially among those aged 18–25. Similar findings were reported for Brazil.Citation25 As screening of women aged less than 25 years is not recommended,Citation3 screening in that age group should be actively discouraged as it uses scarce resources.

A pre-condition to scaling up services is to assure an adequate laboratory infrastructure to read smears and to treat positive women. Provinces that screen a broader age range and with higher frequency than the National Programme guidelines recommend might be limiting their ability to increase coverage for women who need it most, as not all provinces have the infrastructure and human resources to read a greatly increased number of smears. On the other hand, there is no evidence that screening annually in any age group results in greater efficacy.Citation3 In addition to screening an effective programme must assure that women receives their results in a timely manner, that those with abnormal results have colposcopic (and eventually biopsy) evaluation, and that women with pre-cancerous lesions are adequately treated.Citation26 Adherence of provinces with limited resources to national guidelines would allow efforts and resources to be concentrated on women at higher risk of developing cervical pre-cancer and cancer. This will certainly require a participatory process in which national and provincial health authorities agree to use national programme guidelines.

Our results also showed that women aged 65 and over had a lower probability of having been screened in the previous two years, which is consistent with previous evidence.Citation8,27 Thirty per cent reported never having been screened. This is worrying because women in this age group are at high risk for cervical cancer, and under the current national guidelines will no longer have the opportunity to be screened. The World Health Organization recommends that in developing countries, women who have never previously been screened and are older than age 60 should be screened once.Citation28 Programmatic strategies should assure that all women aged 65+ who have never had a Pap test are screened at least once. However, in provinces with limited resources, priority should be given to screening women aged 35–64.Citation3

Our study shows that there were also marked geographical differences in screening coverage. Women from the Northwest and Northeast regions were almost three times more likely to be under-users. These regions have the country highest cervical cancer mortalityCitation1 and are the least developed areas of the country. Some primary health care centres in these provinces face serious infrastructure problems. Very often they do not have enough health professionals to take Pap smears, and women from remote areas have to travel long distances to be screened from areas where transport systems are poorly developed. In these regions, complementing opportunistic screening with active outrearch to women through, for example, mobile clinics, is essential to increase coverage.

In Argentina, colposcopic examination is very often recommended by health professionals at the same time as Pap screening, as a strategy to increase screening sensitivity.Citation29 This widespread practice might also limit screening in public health centres in regions with limited health infrastructure, i.e primary health care centres with no colposcopes, or where the existing ones are not working, or which have no staff trained to perform colposcopy. It is therefore important to promote Pap screening alone as the primary test and referral for colposcopic evaluation and treatment only for women with HSIL. This will allow increasing the capacity of Pap screening in primary health care centres. Colposcopy services should be carried out only for women with abnormalities and not used for primary screening.Citation26 Centralisation of colposcopy services in high quality units should be considered.

Peru and Colombia have implemented pilot projects in remote and less developed areas using visual inspection based on a see-and-treat approach, as a strategy to reduce the number of visits and reach the highest possible number of high risk women. However, in Argentina, most health professionals are not aware of the advantages of visual inspection with acetic acid (VIA) or with Lugol’s iodine (VILI), which have been evaluated locally as having low sensitivity and specificity.Footnote* There is also strong resistance among health professionals to treat women with abnormal results without biopsy confirmation. A high quality pilot project in remote areas of the Northeast or Northwest regions might provide evidence of whether a see-and-treat approach is feasible and effective in regions where cytology screening and treatment are most deficient.

Conclusions

In Argentina, the most socio-economically disadvantaged women have the least chances to be screened. It is essential to develop strategies to actively reach out to them, especially women living in the Northwest and Northeast Regions. The approach can no longer be opportunistic, focused on family planning or maternal and child health clinics, which mainly see women under 35 years of age.Citation23 Strategies should include organising a call-and-recall system adapted to local resources and infrastructure; contacting women through any health service, especially curative services attended by large numbers of women over 35; and implementing mobile clinics in areas with deficient screening services. They must incorporate the needs and perceptions of poor, older, and unmarried women, and address and reduce socio-economic barriers that limit access to Pap smear screening. Of utmost importance is to provide good quality screening and treatment services that meet women’s needs. Pilot projects using new, alternative technologies should be encouraged in less developed regions. Training and promotion workshops for health professionals and managers on the scientific basis and effectiveness of each screening modality is essential to reduce wasteful cervical cancer prevention practices – such as annual screening and screening of young women – that result in an ineffective use of resources and a failure to reduce cervical cancer incidence and mortality rates.

Acknowledgements

The first analysisCitation1 on which this paper is based was prepared for the first systematic evaluation of the National Programme on Cervical Cancer Prevention, carried out in 2007 with funding from the Pan American Health Organization.

Notes

* This report refers to partial results from the LAMS (Latin American Screening) study.Citation30

References

- Arrossi S, Paolino M. Argentina. Diagnóstico de Situación del Programa Nacional de Prevención de Cáncer de Cuello de Utero, y Programas Provinciales. Informe Técnico. Oficina Panamericana de la Salud. (In press 2008).

- J Ferlay, F Bray, P Pisani. GLOBOCAN 2002. Cancer Incidence, Mortality and Prevalence Worldwide. International Agency for Research on Cancer, Cancer Base No.5, Version 2.0. 2004; IARC Press: Lyon.

- International Agency for Research on Cancer. Cervix cancer screening. IARC working group on the evaluation of cancer preventive strategies. 2004; IARC Press: Lyon.

- S Arrossi, R Sankaranarayanan, DM Parkin. Incidence and mortality of cervical cancer in Latin America. Salud Pública de México. 45: 2003; S306–S314.

- Ministerio de Salud de la Nación. Primera Encuesta Nacional de Factores de Riesgo. Buenos Aires, Ministerio de Salud. 2006

- E Gakidou, S Nordhagen, Z Obermeyer. Coverage of cervical cancer screening in 57 countries: low average levels and large inequalities. PLoS Medicine. 5(6): 2008

- G Ronco, N Segnan, A Ponti. Who has Pap tests? Variables associated with the use of Pap tests in absence of screening programmes. International Journal of Epidemiology. 20(2): 1991; 349–353.

- E Cabeza, M Esteva, A Pujol. Social disparities in breast and cervical cancer preventive practices. European Journal of Cancer Prevention. 16(4): 2007; 372–379.

- Ministerio de Salud de la Nación. Encuesta Nacional de Factores de Riesgo. At: <www.msal.gov.ar/htm/Site/enfr/index.asp. >.

- Report on the Meeting: Stop Cervical Cancer. Buenos Aires, 19–20 June 2007. CD-rom, 2008.

- Cervical Cancer Action. Cervical Cancer Action: A Global Coalition to Stop Cervical Cancer. At: <www.cervicalcanceraction.org/home/home.php. >.

- MA Kane, J Sherris, P Coursaget. Chapter 15: HPV vaccine use in the developing world. Vaccine. 24(Suppl. 3): 2006; S132–S139.

- LM Puig-Tintore, X Castellsague, A Torne. Coverage and factors associated with cervical cancer screening: results from the AFRODITA study: a population-based survey in Spain. Journal of Lower Genital Tract Disease. 12(2): 2008; 82–89.

- R Sankaranarayanan, R Rajkumar, S Arrossi. Determinants of participation of women in a cervical cancer visual screening trial in rural south India. Cancer Detection and Prevention. 27(6): 2003; 457–465.

- B Nene, K Jayant, S Arrossi. Determinants of women’s participation in cervical cancer screening trial, Maharashtra, India. Bulletin of World Health Organization. 85(4): 2007; 264–272.

- A Bingham, A Bishop, P Coffey. Factors affecting utilization of cervical cancer prevention services. Revista Mexicana de Salud Pública. Suppl 3: 2003; S408–S416.

- I Agurto, A Bishop, G Sanchez. Perceived barriers and benefits to cervical cancer screening in Latin America. Preventive Medicine. 39(1): 2004; 91–98.

- EC Lazcano-Ponce, P Najera-Aguilar, E Buiatti. The cervical cancer screening program in Mexico: problems with access and coverage. Cancer Causes Control. 8(5): 1997; 698–704.

- J Hsia, E Kemper, C Kiefe. The importance of health insurance as a determinant of cancer screening: evidence from the Women’s Health Initiative. Preventive Medicine. 31(3): 2000; 261–270.

- EC Lazcano-Ponce, S Moss, A Cruz-Valdez. The positive experience of screening quality among users of a cervical cancer detection center. Archives of Medical Research. 33(2): 2002; 186–192.

- PM Lantz, ME Weigers, JS House. Education and income differentials in breast and cervical cancer screening. Policy implications for rural women. Medical Care. 35(3): 1997; 219–236.

- R Sabates, L Feinstein. The role of education in the uptake of preventative health care: the case of cervical screening in Britain. Social Science and Medicine. 62(12): 2006; 2998–3010.

- J Bradley, L Risi, L Denny. Widening the cervical cancer screening net in a South African township: who are the underserved?. Health Care for Women International. 25: 2004; 227–241.

- INDEC. Encuesta Complementaria de Pueblos Indígenas. INDEC 2008. At: <www.indec.mecon.ar. >.

- CM Nascimento, J Eluf-Neto, RA Rego. Pap test coverage in São Paulo municipality and characteristics of the women tested. Bulletin of Pan American Health Organization. 30(4): 1996; 302–312.

- R Herrero, C Ferreccio, J Salmeron. New approaches to cervical cancer screening in Latin America and the Caribbean. Vaccine. 26(Suppl): 2008; L49–L58.

- E Calle, WD Flanders, MJ Thun. Demographic predictors of mammography and Pap smear screening in US women. American Journal of Public Health. 2: 1993; 53–60.

- AB Miller, S Nazeer, S Fonn. Report on Consensus Conference on cervical cancer screening and management. International Journal of Cancer. 86: 2000; 440–447.

- Sociedad Argentina de Patología del Tracto Genital Inferior y Colposcopía. At: <www.colpoweb.org/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=13&Item_id=28. >.

- LO Sarian, SF Derchain, P Naud. Evaluation of visual inspection with acetic acid (VIA), Lugol’s iodine (VILI), cervical cytology and HPV testing as cervical screening tools in Latin America. Journal of Medical Screening. 12(3): 2005; 142–149.