Abstract

Viet Nam has experienced rapid social change over the last decade, with a remarkable decline in fertility to just below replacement level. The combination of fertility decline, son preference, antenatal sex determination using ultrasound and sex selective abortion are key factors driving increased sex ratios at birth in favour of boys in some Asian countries. Whether or not this is taking place in Viet Nam as well is the subject of heightened debate. In this paper, we analyse the nature and determinants of sex ratio at birth in Viet Nam, including a small family size norm, recent reinforcement by the Government of the “one-to-two child” family policy, traditional son preference, easy access to antenatal ultrasound screening and legal abortion, and an increase in the proportion of one-child families. In order to prevent an increased sex ratio at birth in Viet Nam, we argue for the relaxation of the one-to-two child family policy and a return to the policy of “small family size” as determined by families, in tandem with a comprehensive approach to promoting the value of women and girls in society, countering traditional gender roles, and raising public awareness of the negative social consequences of a high sex ratio at birth.

Résumé

Ces dix dernières années, le Viet Nam a connu des changements sociaux rapides, avec une baisse remarquable de la fécondité qui est désormais juste au-dessous du taux de remplacement. Le déclin de la fécondité, la préférence pour les garçons, l’utilisation des ultrasons pour déterminer le sexe du fłtus et l’avortement sélectif sont autant de facteurs qui expliquent les taux de masculinité élevés à la naissance dans certains pays asiatiques. Déterminer si c’est ou non le cas au Viet Nam suscite des débats animés. Dans cet article, nous analysons la nature et les déterminants du rapport de masculinité à la naissance au Viet Nam, notamment la norme de la famille peu nombreuse, le renforcement récent par le Gouvernement de la politique de limitation à un ou deux enfants par famille, la préférence traditionnelle pour les garçons, l’accès aisé aux échographies prénatales et à l’avortement légal, et l’accroissement de la proportion des enfants uniques. Afin d’éviter que le rapport de masculinité ne s’élève au Viet Nam, nous plaidons en faveur de l’assouplissement de la politique familiale et d’un retour à la politique de la famille de petite taille, déterminée par les parents, en association avec une approche globale pour promouvoir la valeur des femmes et des filles dans la société, contrer les rôles traditionnellement dévolus à chaque sexe et sensibiliser l’opinion aux conséquences néfastes d’un rapport élevé de masculinité à la naissance.

Resumen

En la última década, Viet Nam ha experimentado un acelerado cambio social, con un sorprendente descenso del índice de fertilidad a justo por debajo del nivel de reposición. La combinación de dicho descenso, la preferencia por hijos varones, la determinación prenatal del sexo fetal con ultrasonido y el aborto por selección del sexo son factores importantes que propician un aumento en la proporción de varones entre recién nacidos en algunos países asiáticos. Cada vez se debate más si esto está ocurriendo en Viet Nam. En este artículo, analizamos la naturaleza y los determinantes de la proporción de sexos entre recién nacidos en Viet Nam: la norma de una familia pequeña, la reciente reafirmación por parte del Gobierno de la política de familias con “uno o dos hijos”, la preferencia tradicional por varones, el acceso fácil al tamizaje por ultrasonido prenatal y al aborto legal, y el aumento en la proporción de familias con un hijo. A fin de evitar un aumento en la proporción de varones entre recién nacidos en Viet Nam, abogamos por la relajación de la política de familias con uno o dos hijos y por un retorno a la política de “familias pequeñas” con el tamaño determinado por las familias, conjuntamente con un enfoque integral para promover el valor de las mujeres y niñas en la sociedad, contrarrestar los roles tradicionales de género y crear mayor conciencia de las consecuencias sociales negativas de una alta proporción de varones entre recién nacidos.

Scholars have begun to study the long-term implications of demographic changes in Asia, based on current patterns of declining fertility and an increased sex ratio at birth in some countries.Citation1 In contrast, the sex ratio at birth has shifted in favour of girls in a number of western countries, including CanadaCitation2 and Denmark,Citation3 and among white women in the United States.Citation4Citation5

The sex ratio at birth is usually measured as a ratio of the number of boys born per 100 girls. The normal range is conventionally defined as 105–106 boys born per 100 girls.Citation6 This ratio has been quite stable and consistent over time and across geographical areas, with any substantially different ratio implying intentional interventions, usually to increase the number of boys born. Research has shown that son preference, fertility decline, antenatal sex determination using ultrasound and sex selective abortion are key factors driving increased ratios in favour of boys in Asia.Citation7Citation8

High ratios over the last 30 years have produced a shortfall of women of marriageable age in IndiaCitation9,10 and ChinaCitation11 and have directly and indirectly contributed to gender inequality in those countries. Young men from China, Taiwan and South Korea are increasingly seeking brides overseas, particularly from Viet Nam, and concerns have been raised linking this to the trafficking of young Vietnamese women and increased domestic violence in recipient countries against those who have been trafficked.Citation12Citation13 An increased sex ratio at birth in the 1980s has been correlated with high female infant and child mortality rates in South Korea.Citation14Citation15 Under-reporting of female births, and high female neonatal mortality were also identified as underlying causes contributing to high sex ratios in IndiaCitation16 and in ChinaCitation17Citation18 over the last decade.

In Viet Nam, 78% of married women are currently using contraception, and the country has experienced rapid social change over the last decade, creating a socio-political context similar to China in the 1990s, with a remarkable decline in fertility and slight shifts in the sex ratio (Table 1). The current decline in fertility is predicted to continue to below replacement level of 2.1 in coming years.Citation19Citation20

Analyses of regional demographic trends have generated a debate about whether Viet Nam is facing a shift in its sex ratio that preferences male over female births. The debate was recently heightened when the General Statistics Office disseminated the results of the Population Change Survey 2006, which found a ratio of 110 per 100 nationwide (95% CI, 107—113),Citation20 raising questions as to whether or not the increase could be considered statistically significant.Citation21 Estimates at the regional level varied widely, however. For instance, the Southeast region had the lowest level of 102 (95% CI, 93—111) while the Northeast region had the highest of 122 (95% CI, 113—131).Citation22 This wide a variation raised questions of whether there were methodological problems or these were true differentials in son preference, influenced by social, ethnic or other differences. The trends in the data, and the experience in other Asian countries where similar social and political contexts have produced an increase in sex ratio at birth, suggest that a similar trajectory is possible in Viet Nam.Citation23Citation24

Factors that may affect sex ratio at birth in Viet Nam

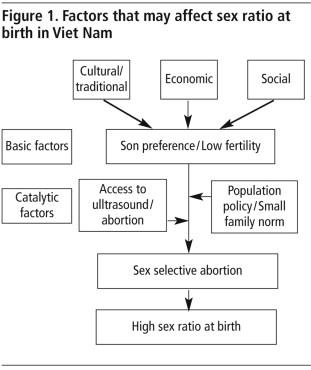

The conjunction of three current factors has the potential to influence sex ratio at birth in Viet Nam. The first is the development of a small family size norm, as a result of socio-economic and political changes, combined with strong Confucian son preference that places pressure on couples to ensure that they have a male child among their progeny. The second is the recent reinforcement of the prescriptive two-child family policy and the local implementation of consequences for breaching this law, which increases the desire for certainty in sex outcomes at birth, and reduces the counter-balancing influence of larger family sizes. The third is wide access to ultrasound and abortion services, with liberal abortion legislation, which facilitates sex selective abortion. Thus, both traditional and modern socio-economic and political factors exist that may affect the sex ratio at birth in Viet Nam ().

Son preference and small family size

Vietnamese society has been strongly influenced by Confucianism, particularly in the North of the country. An important characteristic of Confucianism is a strong preference for sons for cultural, economic and social reasons.Citation25Citation26 The Vietnamese proverb Nhât nam viêt hũu, thâp nũviêt vô (One son is having some, ten daughters is having none) reflects this.

The need for a son is justified in Confucianism as the only way of continuing the family line. Sons carry on the family name, and continue and build on the reputation, tradition and inheritance of family properties. Sons also look after the graves of their ancestors. Failing to have a son is perceived as disrespecting one’s ancestors. Sons are the main labourers in the family, particularly in rural areas. Sons traditionally ensure the inheritance of family properties and are responsible for caring for their parents in old age, especially in rural areas where the social welfare system is poorly developed.

Son preference strongly influences fertility decisions.Citation27 Producing a son reflects on the value of the wife in the eyes of the family and society. Vietnamese women use a range of strategies to secure a son, including traditional folk methods thought to facilitate male contraception, continuing childbearing until a son is born, adopting a male child and terminating female fetuses.Citation28 Our analysis of data from the Population Change Survey 2006 shows that the proportion of one-child families rose from 8.7% in 1999 to 12.3% in 2006.Citation20

Recognising the influences of son preference on people’s fertility behaviour and their family planning practice, the Viet Nam Population Strategy 2001–2010 conceded that:

“Traditional beliefs and customs relating to family size and sex preference are still deeply rooted. ‘Having a son at all costs’ dominates behaviours among many people in many areas, particularly remote, isolated and poor ones.”Citation29

Given access to fetal sex determination through ultrasound and to abortion services, the conditions exist in which sex selection may be adopted. However, this may not be the case in the remote, mountainous areas of the Northwest region, characterised by lower socio-economic development, a higher total fertility rate of 2.4, and many ethnic minority groups, among whom son preference seems to be less pronounced.Citation20

The “one-to-two child” family policy

Viet Nam has implemented a vigorous population policy over the past decades based on the belief that a reduction in population growth would increase per capita gross domestic product. In the 1990s, the population programme strongly promoted the one-to-two child family, a policy drafted by the Viet Nam Commission for Population, Family and Children.Citation30Citation31 The effective implementation of this policy through promotion of contraception meant that services reached the vast majority of the population, and fertility declined from 3.8 in 1989 to 2.3 in 1999. For these achievements, Viet Nam was awarded the United Nations Population Award in 1999.

In the past decade, the emphasis has shifted from birth control to reproductive health, influenced by the 1994 International Conference on Population and Development, which advocated that families should make decisions about family size and other reproductive health matters.Citation32 Adopting these recommendations, the new Viet Nam Population Strategy 2001–2010, issued in early 2000, replaced the obligation of having a one-or two-child family with a more general reference to the need for a small family size, emphasising the need to improve the “quality” of the population.Citation29 Although, the term “small family size” was not clearly defined, this document was important for the development of the Population Ordinance issued by the National Assembly in 2003. For the first time, this high-ranking document officially recognised the reproductive rights of all citizens:

“To decide the timing, number and spacing of births in accordance with their age, health, education, employment and working, income and child-rearing conditions of every individual and on the basis of equality within the couple.”Citation33

This liberalisation of population policy was followed by a slight rise in fertility, reported in the Population Change Survey 2004 (see Table 1), which was generally perceived to be a result of the Population Ordinance 2003. The rise in fertility provided the necessary “evidence” for political stakeholders, who saw fertility as primarily a State concern, as opposed to an individual one. Mass media representations of the “baby boom” advocated the re-instatement of the so-called target programme and more funding for the population programme.

As a result of this advocacy campaign, the Central Executive Committee of the Vietnamese Communist Party reversed the relaxation of the 2003 population policy through Resolution 47, entitled Further Strengthening the Implementation of Population and Family Planning Policy, which was issued in March 2005. It re-introduced the former one-to-two-child family policy and its enforcement. The Resolution expressed State concerns that:

“The surge in population would ruin what has been achieved, reduce socio-economic development and efforts to improve the quality of the population, slow down the country’s industrialisation and modernisation process, and make the country further lag behind… The Population Ordinance and existing policies and regulations, which are not consistent with the two-child campaign, should soon be revised. Policies on encouragement and incentives to communities, families and individuals with good records on population and family planning should be reviewed and revised accordingly.”Citation34

The Resolution introduced fines for Government cadres and Party members who violated the policy, though it was not clear whether this also extended to ordinary citizens. The Resolution, with its commitment that “the whole Party and the whole population should persevere in realising the two-child policy” was disseminated throughout the country, with Party units in all state organisations and bodies, from central down to grassroots level, meeting to discuss its content and implementation. The network of population collaborators has been strengthened and expanded at grassroots level, and more funds provided. This has strengthened conservative factions in the Party and reinforced a social obligation on the part of couples to comply with the policy.

Ironically, an analysis of broader demographic trends has suggested that the increased fertility in 2004 may have reflected a desire by many parents to have a child born in the Lunar Year of the Goat (2003), widely perceived as a good year for reproduction.Citation35 Birth rates in following years showed a fall. A similar phenomenon was documented in Korea.Citation36

In 2007, which happens to be the 30th anniversary of the collaboration between the Vietnamese Government and UNFPA, a new Government structure was proposed, and the number of ministries and central committees was reduced from 26 to 22. The Viet Nam Commission for Population, Family and Children was split into three parts, with the population-related units downsized to a Department on Population, within and administered by the Ministry of Health.

In the most recent political development, in June 2008, a proposal for a new Law on Population was placed on the agenda, aimed at superseding the Population Ordinance 2003. It is expected to be submitted to the National Assembly for review by the end of 2009. It proposes three possible options for regulating family size for discussion: each family should remain small; each family should have one or two children; each family must have only one or two children.Citation37 These options are distinguished by the extent of obligation on parents to have only one or two children, and whether it is voluntary or compulsory.

The proposal reflects current tensions with regard to the direction in which the population policy and programme should move. The long-term impact, if any, on sex ratio at birth cannot yet be assessed, but there are two possible short-term implications. Firstly, a more punitive policy may increase pressures on couples who already have two daughters and desire a son, pitting the desire for a son against State penalties, particularly for those who work in the public sector or who are Party members. A 1998 study found that women with children but without a son had significantly higher rates of intrauterine device discontinuation and were more likely to report having an additional child as a result of contraceptive failure in order to avoid criticism for exceeding the then two-child limit.Citation38

As with implementation of the 1990s policy, the one-to-two child family policy has been unequally enforced, with less enforcement in rural areas and among ethnic minorities. Members of the Party and those employed by Government are more exposed to disciplinary measures.Citation39 Party membership and government employment, however, provide more secure social economic and educational status, with greater access to information and health services, including sex selection as a possible way of reconciling individual desires with institutional obligations.

Secondly, assuming fertility stays at or declines below replacement level, in line with current trends and the ascendency of political support for a one-to-two child policy, choices resulting from strong son preference in families of one to two children are likely to affect the sex ratio at birth.Citation40 The role of sex identification during ultrasound scanning and sex selective abortion is increasingly important in supporting these decisions.

Access to ultrasound and abortion services

Ultrasound has been the most frequently used method for identification of sex since the mid-1990s. Ultrasound services have grown and become a profitable business for service providers and suppliers.Citation41Citation42 Several scholars have attributed high sex ratio at birth in Asia, at least in part, to increasing availability of antenatal sex detection.Citation43Citation44 Trans-abdominal ultrasound can detect the sex of the fetus with accuracy reported between 80%Citation45 and even 98.7%Citation46 at the 12th week of gestation.

In Viet Nam, ultrasound services are provided as a part of the reproductive health programme, for detecting fetal anomalies. They are widely accessible throughout the country in most secondary health facilities. Utilisation is high, with evidence of overuse reported in Hanoi of 6.6 scans during pregnancy on average, which women say is for regular reassurance that the baby is OK.Citation47 At a cost of about 40,000–50,000 VND per scan (equivalent to US$ 2.50–3.50), the majority of pregnant women can afford several scans, which also allow them to discover fetal sex. As a consequence, a large proportion of women (86% of urban women and 63% of rural women according to the Population Change Survey 2006) are aware of the sex of their baby before delivery. Most obtained this information through ultrasound (94% urban and 92% rural women, respectively).Citation22

Abortion is legal in Viet Nam and safe abortion is provided as part of the reproductive health programme.Citation48 The Law on the Public Health provides that: “Women shall be entitled to have an abortion if they so desire”,Citation49 with sick leave for abortion authorised under the Labour Code of Viet Nam.Citation50 Abortion is currently accessible free of charge in the public ealth services and at a cost of about 120,000–150,000 VND (US$8–10) in private clinics. While abortions in the first trimester are performed at the woman’s request at primary and secondary health facilities, abortions in the second trimester are still accessible, but require admission to public tertiary maternity hospitals.

In response to public concern about sex selection, the Vietnamese Government issued Decree 114/2006/ND-CP in October 2006, which imposes fines of 500,000–15,000,000 VND (US$30–937) on people who promote or practise abortions on the basis of fetal sex, or who use traditional practices to determine fetal sex.Citation51 The decree does not, however, specify how this regulation would be enforced in a situation where there is access to ultrasound and abortion services. The Population Ordinance 2003 also had an article forbidding sex selection in any form,Citation33 though there is no evidence of action being taken under this article.

Conclusions and recommendations

Son preference is deeply rooted in Vietnamese culture and society, and has changed little despite recent socio-economic development and political interventions. It appears to have been integrated into modern perceptions of small family size, with the one-child family an increasingly acceptable norm.

Given this context, there may be unintended negative synergies between the one-to-two child family policy, legal abortion, easily available diagnostic ultrasound and son preference, which together may lead to an increase in sex selection with a negative effect on the sex ratio at birth.

Of the possible interventions that might disrupt these synergies and prevent any population-level consequences being established, we suggest four options: regulation of sex identification through ultrasound; prohibition of sex selective abortion; addressing gender equity, including educating the population about the negative consequences of an unbalanced sex ratio and promoting the role of girls and women in family and society; and relaxing the one-to-two child family policy by opting for the policy that each family should remain small in the new Law on Population.

Rapid technical development, specifically in antenatal ultrasonography, has made early second trimester identification of sex possible. Sex selective abortion is unrealistic without the assistance of ultrasound. If sex determination is a part of ultrasound procedures, then the question is what the appropriate time to disclose such information to couples? Whatever the answer, however, attempts to regulate ultrasound and ban sex selective abortion in India and China have been ineffective and unenforceable.Citation9,52,53 Although they appear to be easy options, they often limit access to and use of antenatal care and safe abortion services. They may encourage doctors and patients to fabricate reasons for termination, constrain an otherwise socially accepted practice, and create a profitable underground market for illegal sex selective abortion, with all the attendant health problems.

Policymakers need to recognise that the restriction of reproductive rights and the political drive to lower population are themselves contributors to the increasing sex ratio at birth in Asia. However, another thing that can be done is to provide appropriate information for women, their partners and families who seek for abortion beyond the 12th week of pregnancy, especially those with girl children. They may consider these only as personal issues with individual benefits, and may change their views if they understand that son preference and sex selection may in the aggregate have harmful consequences for society as a whole, including for their sons.

Fewer girls than boys in a society does not improve gender equity.Citation23 Gender inequity and inequality are at the root of son preference but simplistic initiatives to reduce discrimination against girls have had little effect to date on sex ratios. In Viet Nam attempts have been made over the past decade to promote gender equity in population and development programmes, but with few demonstrable results.Citation54 Studies in China show that socio-economic development and education programmes for women are not in themselves sufficient to prevent a rising sex ratio at birth.Citation55 In South Korea, on the other hand, the sex ratio at birth has fallen with development, industrialisation and urbanisation.Citation56 However, promoting the value of women and girls in society and countering traditional gender roles requires a radical social approach, based on a thorough understanding of the gender differentials across society. Information, education and communication are a crucial component of such policy responses. Information needs to be disseminated among various stakeholders, including health and population policymakers, health professionals, civil society and the general public.

While long-term changes in gender equity are an integral part of necessary policy responses, the time frame required may be too long to avoid an increasing sex ratio at birth. What is immediately possible is the relaxation of the one-to-two child family policy, reasserting family autonomy as regards what constitutes small family size alongside raising public awareness of the social consequences of a high sex ratio at birth. Given the widespread availability and use of contraception, abortion and ultrasound, not only family size but also sex composition of children can become quite controllable for couples. Citation57Citation58 For some families, a third child may be desirable, and although allowing this may lead to an increase in the total fertility rate, it could also prevent a rising sex ratio at birth.

Lastly, to better inform any policy response, the limitations of currently available data must be overcome. Good quality demographic data are needed to monitor sex ratio at birth in Viet Nam in the coming years, using currently available population data, including birth registration data and birth records in the health system, triangulated against census data. We also support the enhancement of the national vital registration systems that will enable accurate, ongoing monitoring.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported financially by the Australian Agency for International Development (AusAID). We would like to thank the University of Queensland, School of Population, Australia, for technical support in the development of this paper. Where documents quoted were not available in English, the text was translated by the authors.

References

- AM Boer, VM Hudson. The security threat of Asia’s sex ratios. Johns Hopkins University School of Advanced International Studies Review. 24(2): 2004; 27–43.

- BB Allan, R Brant, JE Seidel. Declining sex ratios in Canada. Canadian Medical Association. 1997; 37–41.

- RJ Biggar, J Wohlfahrt, T Westergaard. Sex ratios, family size, and birth order. American Journal of Epidemiology. 150(9): 1999; 957–962.

- M Marcus, J Kiely, F Xu. Changing sex ratio in the United States, 1969–1995. Fertility Sterility. 70(2): 1998; 270–273.

- TJ Mathews, BE Hamilton. Trend analysis of the sex ratio at birth in the United States. Natural Vital Statistic Reproduction. 53(20): 2005; 1–17.

- ICW Hardy. Sex Ratios: Concept and Research Methods. Chapter 14 Human sex ratios: adaptations and mechanism, problems and prospects. 2002; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, 288.

- BD Miller. Female selective abortion in Asia: patterns, policies and debates. American Anthropologist. 103(4): 2001; 1083–1095.

- N Barber. Sex ratio at birth, polygyny, and fertility: a cross national study. Social Biology. 51(1/2): 2004; 71.

- F Arnold, S Kishor, TK Roy. Sex selective abortions in India. Population and Development Review. 28(4): 2002; 759–785.

- P Jha, R Kumar, P Vasa. Low male-to-female sex ratio of children born in India: national survey of 1.1 million households. Lancet. 367(9506): 2006; 211–218.

- SW Mosher. China’s one-child policy: twenty-five years later. Human Life Review. 32(1): 2006; 76.

- Hong XNT. Marriage migration between Vietnam and Taiwan: a view from Viet Nam. International Conference on Female Deficit in Asia: Trends and Perspectives. Singapore, 5–7 December 2005.

- Duong LB, Belanger D, Hong KT. Transnational migration, marriage and trafficking at the China-Viet Nam border. International Conference on Female Deficit in Asia: Trends and Perspectives. Singapore, 5–7 December 2005.

- MK Choe. Sex differentials in infant and child mortality in Korea. Social Biology. 34(1–2): 1987; 12–25.

- CB Park. Preference for sons, family size and sex ratio: an empirical study in Korea. Demography. 20(3): 1983; 333–352.

- Bhat PNM, Zavier AJF. Factors influencing the use of prenatal diagnostic techniques and sex ratio at birth in India. International Conference on Female Deficit in Asia: Trends and Perspectives. Singapore, 5–7 December 2005.

- D Lai. Sex ratio at birth and infant mortality rate in China: an empirical study. Journal Social Indicators Research. 70(3): 2005; 313–326.

- Z Wu, K Viisainen, E Hemminki. Determinants of high sex ratio among newborns: a cohort study from rural Anhui province, China. Reproductive Health Matters. 14(27): 2006; 172–180.

- Population and Labour Department/General Statistics Office of Viet Nam. Population change and family planning survey 2007: major findings. 2008; Statistics Publishing House: Hanoi.

- Population and Labour Department/General Statistics Office of Viet Nam. Population change survey 1/4/2006: major findings. 2007; Statistics Publishing House: Hanoi.

- G Santow. Review data on fertility, mortality and sex ratio at birth as derived from the 2006 Population Change Survey. November. 2006; UNFPA: Hanoi.

- NV Phai. Sex ratios at birth in Viet Nam through national censuses and annual population change surveys. 2006; General Statistics Office: Hanoi.

- D Belanger. Sex selective abortion: short-term and long-term perspectives. Reproductive Health Matters. 10(19): 2002; 194–197.

- Wei C. Sex ratios at birth in China. International Conference on Female Deficit in Asia: Trends and Perspectives. Singapore, 5–7 December 2005.

- D Belanger. Son preference in a rural village in North Vietnam. Studies in Family Planning. 33(4): 2002; 321–334.

- D Belanger. Indispensable sons: negotiating reproductive desires in rural Viet Nam. Gender, Place and Culture. 13(3): 2006; 251–265.

- J Haughton, D Haughton. Son preference in Vietnam. Studies in Family Planning. 26(6): 1995; 325–327.

- Institute for Social Development Studies. New “common sense” family planning policy and sex ratio at birth in Viet Nam: Findings from a qualitative study in Bac Ninh, Ha Tay and Binh Dinh. 4th Asian and Pacific Conference on Reproductive and Sexual Health and Rights. Hyderabad: UNFPA; 2007.

- Viet Nam Commission for Population Family and Children. National Strategy on Population 2001–2010. 2000; VCPFC: Hanoi.

- National Committee for Population Family Planning. Population and Family Planning Policies and Strategy to the Year 2000. 1993; NCPFP: Hanoi.

- DM Goodkind. Vietnam’s one-or-two-child policy in action. Population and Development Review. 21(1): 1995; 85–111.

- UN Population Fund. Asia and the Pacific: A Region in Transition. 2002; UNFPA: New York.

- Parliamentary Committee for Social Affairs. Population Ordinance. 2003; PCSA: Hanoi.

- Central Party Executive Committee. Resolution 47-NQ/TW. Further strengthening the implementation of population and family planning policy. Hanoi: 2005.

- UN Population Fund. 2005 Population Change Survey: What the data tell us?. 2006; UNFPA: Hanoi.

- J Lee, M Paik. Sex preference and fertility in South Korea during the year of the Horse. Demography. 43(2): 2006; 269.

- UNFPA. Second National Technical Advisory Group Meeting. Ha Long, 26–27 June 2008.

- A Johansson, NT Lap, VK Diwan. Population policy, son preference and the use of IUDs in North Viet Nam. Reproductive Health Matters. 6(11): 1998; 66–76.

- D Belanger, KTH Oanh, L Jianye. Are sex ratios at birth increasing in Vietnam?. Population. 58(2): 2003; 231–250.

- Ministry of Health of Viet Nam. Understanding factors influencing abortion among women having only girls in reproductive health facilities. 2007; Viet Nam Family Association: Hanoi.

- M Gupta, PN Mari Bhat. Fertility decline and increased manifestation of sex bias in India. Population Studies. 51(3): 1997; 307–315.

- CB Park, NH Cho. Consequences of a son preference in a low fertility society: imbalance of the sex ratio at birth in Korea. Population and Development Review. 21(1): 1995; 127–151.

- TH Hull. Recent trends in sex ratios at birth in China. Population and Development Review. 16(1): 1990; 63–83.

- S Johansson, O Nygren. The missing girls of China: a new demographic account. Population and Development Review. 17(1): 1991; 35–51.

- B Whitlow, M Lazanakis, D Economides. The sonographic identification of fetal gender from 11 to 14 weeks of gestation. Ultrasound Obstetrics Gynaecology. 13(5): 1999; 301–304.

- Z Efrat. First trimester diagnosis of gender. Ultrasound in Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 13: 1999; 305–330.

- T Gammeltoft, TTN Hanh. The commodification of obstetric ultrasound scanning in Hanoi, Viet Nam. Reproductive Health Matters. 15(29): 2007; 163–171.

- Ministry of Health of Viet Nam. National Strategy on Reproductive Health Care for the period 2001–2010. 2001; Reproductive Health Department, Ministry of Health of Viet Nam: Hanoi.

- National Assembly of Viet Nam. Law on Protection of People’s Health. 1989; Parliamentary Committee for Social Affairs, National Assembly of Viet Nam: Hanoi.

- National Assembly of Viet Nam. Labour Code of the Socialist Republic of Viet Nam. 1994; National Political Publishing House: Hanoi.

- Viet Nam Commission for Population Family and Children. Decree 114/2006/ND-CP. Guideline for administrative publishment and fines on violation of population and children policies. Hanoi: VCPFC; 2006.

- J Banister. Shortage of girls in China today. Journal of Population Research. 21(1): 2004; 19–45.

- B Ganatra. Maintaining access to safe abortion and reducing sex ratio imbalances in Asia. Reproductive Health Matters. 16(31 Suppl): 2008; 90–98.

- D Belanger, KT Hong. Single women’ experience of sexual relationships and abortion in Hanoi. Reproductive Health Matters. 7(14): 1999; 71–82.

- P Lofstedt, L Shusheng, A Johansson. Abortion patterns and reported sex ratios at birth in rural Yunnan, China. Reproductive Health Matters. 12(24): 2004; 86–95.

- W Chung, MD Gupta. The decline of son preference in South Korea: the roles of development and public policy. Population and Development Review. 33(4): 2007; 757–783.

- M Lappe, P Steinfels. Choosing the sex of our children. Hastings Centre Report. 4(1): 1974; 1–4.

- WH James. Further evidence that mammalian sex ratios at birth are partially controlled by parental hormone levels around the time of conception. Human Reproduction. 19(6): 2004; 1250–1256.