Every decade of my adult life has been marked by at least one traumatic event related to my reproductive system. In my 20s I had surgery several times to remove benign fibro-adenomas in my breasts, a consequence of being on the birth control pill, I was told. In my 30s it was the second trimester loss of a much-wanted pregnancy, a loss that I grieved over silently for many years. In my 40s it was a partial hysterectomy, a stark and early reminder of the aging process. And my 50s began in 2006 with a diagnosis of breast cancer.

Given my track record, one would imagine that I would take the most recent diagnosis in my stride. Somehow, however, this one was different. Looking back, my memory of breast cancer can best be described as a surreal montage of discrete events, simultaneously vivid and distant, each tinged with some combination of sadness, anger, fear and terror, but all made more bearable because of the support and love of my family and friends and the quality and compassionate care offered by the various medical personnel I encountered.

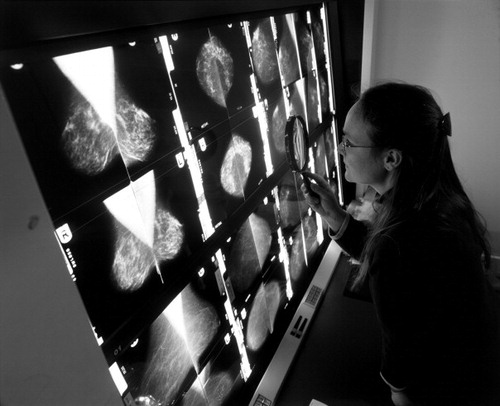

The most vivid memory I have is of the moment when I felt the lump in my right breast. I was convinced that it was a figment of my imagination, created out of empathy for my sister, Radhika, who had informed me just that day that she had been diagnosed with breast cancer. It seemed terribly unfair that she, my baby sister, should have to go through yet another medical trauma. Ten years before she had undergone brain surgery as treatment for adult-onset epilepsy, a condition that had chipped away, one seizure at a time, at her ebullient and confident personality. The brain surgery, despite its significant risks, seemed minor in comparison to the damage caused by the seizures. Fortunately it was successful, leaving her whole again till the fall of 2006, when her mammogram revealed a 0.5 cm lump in her left breast. The needle biopsy confirmed the worst. I took the news poorly and resolved on the spot that I would drop all I was doing and travel across the country to the west coast where she lived to be with her through her treatment. I also resolved to do a self-exam that night, which is how I detected the lump in my breast and went to have a mammogram.

The mammogram, amazingly, found nothing suspicious. I was relieved and experienced severe survivor’s guilt because it didn’t seem fair that I had been spared that devastating diagnosis when my sister had not. It was my sister who gently urged me to see my physician despite the clear mammogram, and it was my sister who cried with me when the results of my needle biopsy confirmed that mine – a 2.5 cm lump deep inside my right breast, dangerously close to my rib cage – was malignant, too. And so it was that my sister and I, with no prior family history of cancer, went through surgery, chemotherapy, and radiation for breast cancer at roughly the same time, me on the east coast, she on the west; two sisters caught in an unbelievable and hideous coincidence, travelling parallel paths, coping with the possibility of a tragic destination.

We are often asked if we know why and how we both developed breast cancer. No, we do not. I went through genetic counselling, primarily because my sister and I were concerned for our daughters and the genetic legacy we may be passing on to them. The tests were negative; there was no trace of any genetic link. Although our near-simultaneous diagnosis is startling to others who learn about it, my sister and I have spent very little time discussing what in our shared environment could have led to a common diagnosis. I am convinced that well-meaning friends, who repeatedly hypothesise aloud to us about the various environmental forces that may have caused our illness, do so more out of fear of their own vulnerability than a concern about us. Their fear is understandable but has been futile to me and my sister as we have coped with the consequences of those unknown causes.

The only up-side of this bizarre coincidence was that we had a ready-made support group of two! When one wept, the other stayed strong; when one talked about that difficult-to-express fear of dying, the other was calm and pragmatic. Both of us resented the way the cancer had intruded into our happy lives and we felt angry more often than sad. We also resolved never to accept the identity of a cancer survivor – we were and would always continue to be just Radhika and Geeta. We refused to let the cancer define us or become who we are.

The second vivid memory is actually of three separate events that are rolled into one heavy ball of sorrow: those moments when I had to break the news of my diagnosis to my husband, daughter and father. To be the cause of anxiety and sorrow for those whom I loved the most, and not to be able to do anything to help them cope, was unbearable. I called my husband, Arvind, from a public phone in the hospital in front of waiting patients, shamelessly crying as I uttered the very words that he and I, the night before, had convinced ourselves would never need to be said. He rushed over to be with me and stayed by my side, both literally and figuratively, from then right to the end of my treatment. I must have exhausted him but he rarely showed it. He put up with my many complaints and my unpredictable moods; supported me when I chose to reject the expensive wig I had bought and wear an African turban instead; made me laugh in my darkest moments; and most importantly, maintained a normalcy in our relationship by arguing and quarrelling with me just as much as he did before I became sick!

My daughter, Nayna, was similarly supportive and loving throughout my treatment, returning home from college repeatedly to be with me despite being just six months away from graduation. She was away on a college-sponsored research trip when I got the diagnosis, so I waited for her to return to tell her in person. As a 20-year old who up to that point had led a fairly charmed life, she reacted with anger and resentment toward the forces out there that would dare to shake the very foundation of her world by threatening the well-being of not just her beloved aunt but also her mother. Her intense sorrow and sense of being totally out of control were to be expected. All I could do was to hold her and apologise repeatedly. Despite years of studying the impact of HIV and AIDS on women worldwide, this was the first time I had personally felt the weight of the burden women carry when they have to share the news of their ill-health with their children.

We are very close, my daughter and I, bonded in an almost magical way. She was born on my 29th birthday and was by far the best birthday gift I have ever received. There was little I could do to protect her from the sense of insecurity that children feel when a parent is vulnerable, or my beloved 85-year-old father, who had to cope with the news that both his daughters were now battling cancer. We had lost our mother, his wife and companion of 50 years, just two years earlier and now he had to bear the anxiety brought on by this news all on his own. He was away in Mumbai at the time and immediately cut short his vacation to return home to support me and my sister.

My memory of the various medical procedures and treatments is diffuse and somewhat confused, but I remember well each of the medical and non-medical personnel at the Washington Hospital Center’s Cancer Institute who went out of their way to treat me with compassion and care. Dr Karen Smith and Dr Marc Boisvert, my medical oncologist and surgeon, were my caring guides through it all. Their professionalism and thoughtful bedside manner helped my husband and me feel confident that I was getting the best treatment available. They answered all our questions, were available to us at all times, and never once rushed us through an appointment. That quality of care was visible in our interactions with all the staff we encountered at the Cancer Institute.Footnote* I am eternally grateful to each of them and feel blessed to have had access to such high quality care in a world where millions of women are denied the right to such services. In a country that is notorious for its broken health care system, I am also deeply grateful for having had the good fortune and resources to be fully covered by a medical insurance plan that covered most of my costs and never made it difficult for me get the care and treatment my doctors deemed necessary. I am acutely aware of the many who live in the US who do not have the same coverage as they battle illness. That anyone should have to worry about the costs of care or compromise on the best treatment available when trying to cope with a debilitating illness is terribly unjust and inexcusable in a country as richly endowed as the US.

The quality medical care I received made the pain and discomfort that is characteristic of cancer treatment much more bearable. Luckily, my memory of those symptoms today is somewhat out of focus but marked by an overall feeling of intense dread at the thought of ever going through such treatment again. I can list the symptoms – severe exhaustion, painful sores in my mouth, the sharp pain deep inside my bones, that odd sensation in my throat, the nausea, lack of appetite, indigestion, sleeplessness – but, thankfully, cannot recall their intensity today. In dealing with these symptoms my sister and I decided that we would not fall prey to the pressure to be secretive, heroic, brave or self-sacrificing. And so, though I continued to go to work throughout my treatment, I stayed home or left work early whenever I needed to. I talked about my symptoms to anyone who would listen, asked for and took any help that would reduce the discomfort, and complained bitterly when the pain and discomfort were unbearable. Crying, my sister and I had resolved, was a useful way to get rid of the many toxins coursing through our veins, and so we wept liberally when we needed to. But we also resolved not to cave into the temptation to be drama-queens! Breast cancer, with its dreaded treatment and its potential to kill, is very conducive to high drama, but we realised early on that by taking on that mantle we would allow the cancer to take over who we were and we wanted none of that. Our mother, a physician who had treated all our childhood “boo-boos” with a kiss and some cold cream, had taught us well that pragmatism coupled with a forthright call for help when it was needed were the key to coping. So we handled each situation in as practical a way as we could without embroidering it with any more or less emotion than was needed. In retrospect, I think our strategy worked well for us, particularly because we had many loving and patient family members, friends, and colleagues willing to help.

There were only three occasions during my eight-month long treatment when I felt an irresistible urge to give up – to just close my eyes and do whatever was necessary to fade away into oblivion. The first was just after my lumpectomy, when the sight of my bruised, cut-up and sutured chest made me want to climb out of my body and reject it permanently. The second was during a chemotherapy session when Veronica, my regular nurse, was absent and the anaesthetic cream applied to my port did not work. The only way I could cope with the severe pain and burning that resulted when the needle punctured my port was to leave my body and watch from above, a strategy that worked so well that I temporarily considered its value as a permanent solution. The third occasion was when a stab of pain deep inside my thigh bone brought me to my knees while I was shopping alone at a mall far away from home. Just sitting there on the floor waiting for the pain to wash away, being stared at by curious passers-by, made me wonder whether it was all worth it after all. In each instance, the most clichéd of images, my daughter’s smiling face and my husband’s broad shoulders, brought me back into the fight, each time with renewed energy and spirit.

And then, just as suddenly as it began, the treatment was all over and I was able to go back to my daily routine. The highlight during that period was a surprise sing-along party orchestrated for me by my dear friend, Ellen. Knowing my love for singing Broadway and other songs, she organised a sing-along, with my colleague Leslie as guitarist and my neighbor Natalie as pianist! When I returned home that afternoon, I was greeted by 60 of my friends, family members and colleagues, from the many different parts of my life, jammed in my living room, loudly singing “Hello Geeta” to the tune of “Hello Dolly”. They let me know in spirited chorus that they were glad to have me back where I belonged. The love in the room was palpable and I realised as I looked around how each and every one of them had made my experience with breast cancer more bearable.Footnote*

Surely, four kicks in the rear, one for each of the past four decades of my life, should be enough to appease the jealous gods. I will admit that the fear of a recurrence lingers and every now and then intensifies. I am, nevertheless, ever hopeful that my reproductive system will not seek any further attention when I enter my 60s.

Notes

* For the record, I would like to thank Mildred and Dolores, at the hospital reception desk, who greeted me by name every time I visited; Linda, the head nurse who was available to me at all times, helped me navigate my emotions and the complex maze of medical requirements; Veronica, the Irish chemotherapy nurse who with her tenderness made each infusion seem like a breeze; Kimberly, the medical oncology nurse who always made me feel like her most important patient; Mustapha and his team at the radiation treatment center who treated me with the utmost respect, allowing me to maintain my dignity while I bared my breast for all to see; the quiet and unassuming nurse who drew my blood prior to each chemotherapy infusion, whose skill in getting a needle into a vein totally painlessly should be bottled and sold to all nursing students; and the many nurses I encountered in the mammography, surgery, ultrasound, and nuclear medicine departments who made me feel brave even when I was crying out aloud.

* I cannot possibly name the many friends, family members and colleagues whose support and love I counted on during those months of treatment but to each one of them I owe a debt of gratitude that I cannot possibly repay in this lifetime.