It has taken this journal 16 years to focus on reproductive cancers, and there is no excuse for that. There are many others in the field who have equally inexcusably neglected this important health issue for many years in developing countries, where morbidity and mortality are high and specialist services are few. There are many state-of-the-art specialist cancer hospitals in resource-rich countries. A huge amount of research on treatment has been carried out in the past few decades, leading to greatly increased survival rates, especially if cancers are caught early, and good quality, timely treatment with a combination of drugs, surgery and radiotherapy is available. However, treatment is expensive, and in developing countries, out of reach for the vast majority. Women experience extremely painful deaths, and even palliative care is rare.

People who otherwise claim to support integrated and comprehensive sexual and reproductive health care often don’t even mention reproductive cancers,Footnote* let alone think about them. Perhaps it takes getting older, or even getting cancer, to notice that serious sexual and reproductive health problems do not stop happening when we get beyond reproductive age.

The feature papers on cancer in this issue come from Latin America, Africa, and Asia, a good range, but almost all of them are on cervical cancer. Only one paper, one letter and four personal experience papers are about breast cancer. This is not enough. Only one personal history is about prostate cancer. Along with a paper on human papillomavirus vaccination for boys as well as girls, it is the only paper that mentions cancer in men at all in this issue. Nor are there any papers about ovarian, uterine or other less common reproductive cancers.

In a conference on ovarian cancer earlier this year in London, I learned that complex research into treatment for ovarian cancer was going on, exploring issues from genetic mapping of cancer cells to molecular diagnostics, tumour targeting with personalised drugs, ovarian screening with ultrasound and attempts to identify signs and symptoms so that women can know to seek screening earlier. But it was attended mainly by clinicians and high-level researchers in these new fields of medicine, plus a few representatives of survivor support groups. The broader base of women’s health advocates were almost entirely absent.

A history of neglect

I’m glad to be able to publish so much on cervical cancer. It is the most common cancer in women in developing countries, with a high rate of mortality, in spite of being the most preventable and treatable form of cancer. The main reason it is getting attention now is because of the research and development work, mainly initiated in the United States over the past decade and more, to find simpler cervical screening techniques to replace Pap smears. More recently, two pharmaceutical companies have come out with vaccines to protect against infection with two high-risk types of human papillomavirus (HPV), the main causative factor in 70% of cervical cancers. While all that costly R&D work has been going on, however, almost no money or resources worth mentioning have gone into implementing any form of screening, let alone early treatment, for cervical cancer and its precursors in the countries that most need it. That is a different form of neglect, and is equally inexcusable. How quickly that will change now that vaccinations and the technique of visual inspection exist remains to be seen.

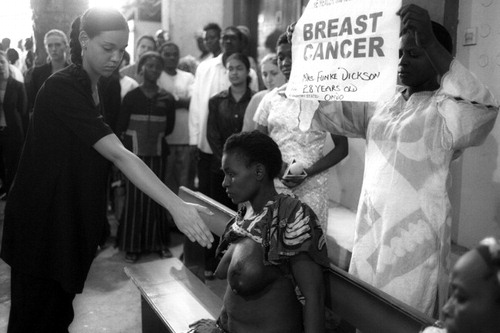

The picture that emerges from this journal issue is of how poorly most developing countries handle reproductive cancers, when they do anything about them at all. Even in the UK, as I heard at the ovarian cancer conference, cancer was neglected before 1995, diagnosis was often only of advanced disease and survival rates were poor. National strategies developed only in 1995, 2000 and 2007 have greatly changed that picture. But low-resource countries lag far behind. The papers in this journal issue contain a stark indictment of the inequity between rich and not-rich countries as regards attention to cancer. The papers of five cancer survivors in this issue describe the first-class diagnosis and treatment they received, not just in the USA, UK and Australia, but also in Mexico and Brazil. But alongside them are the histories of South African women with advanced cervical disease, whose fear even to mention their main symptom, vaginal bleeding, led to a lack of suspicion of cancer among the service providers who saw them, and the failure to carry out cervical screening even though the providers had been trained to do so and prevalence is high. There were repeated incorrect diagnoses even when the women went back several times; unconscionable delays not only in correct diagnosis, but also in referral for treatment and before treatment was started. As with maternal deaths, cancer is cruelly and unnecessarily cutting short women’s lives.

Technology can’t work without health systems and health workers

The sudden richness of choice of preventative and screening methods for cervical cancer is impressive. HPV vaccination can prevent transmission of HPV, so that cervical abnormalities and cancer may never develop. Visual inspection of the cervix with acetic acid (VIA) has been shown to be more successful than Pap smears in some low-resource settings at detecting pre-cancerous lesions (mainly because the Pap smear taking and reading are so poor, not because the technique is deficient). HPV DNA testing is considered by many to be the best and easiest method of screening. If carried out universally, it could reduce the need for any further screening for most women, and resources could be concentrated on women who test positive for high-risk forms of HPV. Both HPV DNA testing and VIA can be done by trained nurses though the HPV DNA test does require laboratory reading of results. Cryotherapy as first-line treatment for pre-cancerous lesions can also be done by trained nurses – if there are nurses and if there is equipment and if they are trained and if the clinics and hospitals they need to work in are functioning.

But where is the money and where are the health systems able to develop scaled-up programmes? And how ironic can it be, that HPV DNA tests and HPV vaccines are too expensive for the very countries that need them most – supposedly the countries for which they were developed in the first place? We are asked to wait patiently for a reduced HPV vaccine price of what, US$45, instead of the hundreds of dollars it now costs? This is outrageous. Even the UK isn’t willing to pay for the quadrivalent HPV vaccine, which protects against genital warts as well as HPV. How can poor countries be expected to find the cash?

Do we have to have the same battles with the same profit-hungry western pharmaceutical companies over every last drug and device that is crucial for the public health? Where is the World Health Organization, that should be demanding on behalf of its government members that drug prices must be lowered enough to allow universal access?

And there is another anomaly in how HPV vaccination is being promoted. Why was the vaccine’s safety and effectiveness not tested in boys at the same time as in girls? Why are there no plans for vaccinating boys against HPV? Don’t men sexually transmit HPV? Surely we should be beyond the blinkered gender and sexuality perceptions that put all the onus for protecting sexual health on girls and women. Here are the facts. Men get HPV as well as women. Men can transmit it sexually to women and to other men too. Men get genital and anal HPV-associated cancers, not just women. So, shouldn’t boys be vaccinated at the same time as girls, before sex begins? Some data indicate that anal cancer rates in men who have sex with men might exceed cervical cancer rates in women; and that more anal than cervical cancers might be prevented by HPV vaccination.Citation2 That is certainly a little known piece of information.

The papers in this journal issue on operations research to test VIA programmes in Thailand and Ghana, and in Bangladesh, and a paper from South Africa on why its cervical cancer programme has not succeeded, show that without leadership, strengthened health services, resources and equipment, sufficient training and skilled staff, established call-and-recall systems, and close links between screening and treatment, even simple VIA followed by simple cryotherapy treatment simply will not reach enough women to reduce the burden of disease from cervical cancer that so many women in poor countries are experiencing today.

Epidemic levels of cancer

Cervical cancer is at epidemic proportions globally in all developing countries. Breast cancer is also at epidemic proportions, not just in rich countries but increasingly in middle-income countries as well, as those countries begin to achieve what Western powers call development. Today, 55% of breast cancer deaths occur in low-and middle-income countries. Rates in Japan, Singapore and Korea have doubled or tripled in the past 40 years, for example, while rates in Africa have doubled.Citation3

One paper in this journal issue calls for as much attention to these epidemics as to the HIV epidemic. But where is the international women’s health movement that can match the HIV access-to-treatment movement, informing women, organising women, on the streets and in the parliaments demanding resources for cancer prevention and treatment? We are much depleted as a political force. There are publications, conferences and meetings coming out of our ears, but in most places, when we organise ourselves for action and for change, we are few.

Population-based screening

Call-and-recall systems are crucial for breast and cervical cancer screening, and may be recommended for prostate cancer screening as well if research confirms the value of the PSA test. How many of the countries attempting to introduce VIA and cryotherapy, or mammography, or even just clinical breast examinations, have figured out how to make such a system work in the conditions prevailing in their countries? Papers in this journal issue barely mention this, if at all. Yet screening where there are epidemic levels of cancer requires such a system. In sub-Saharan Africa, for example, which lacks diagnostic equipment and national prevention programmes, only 5% of women are regularly screened for cervical cancer.Citation4 This rate needs to rise to at least 70% to have a major impact on disease.

You cannot wait for women to turn up on their own for screening, or screen them only if they come for other health care, which is what most developing countries who are screening women at all currently do. You cannot waste resources on screening young women either. It is women over 35 who need cervical screening and women over 50 who need mammography. Countries need epidemiological data to know who to target and to match resource allocation to the burden of disease. Women must be informed why they must come for screening and must be invited to come on a constant, rolling schedule basis. Health workers must also ensure that they do come, invitation is not enough. And once they’ve been screened, uptake of treatment must be ensured, as and when required, and follow-up screening in the years after that. This is a complex system; it needs assiduous maintenance, and regular monitoring and improvement.

Prevention, screening and treatment

Knowing the causative factors of a particular cancer can make all the difference. Without this, prevention is far more difficult, if not impossible. For example, over a period of ten years in the UK, high levels of use of hormone replacement therapy increased the numbers of women with breast cancer by 20,000 (Valerie Beral, ovarian cancer conference, April 2008, London). Obesity and alcohol use also increase breast cancer risk. Knowing these things gives women a measure of control and a way to reduce their risk.Citation1 Although cancer is a degenerative disease of ageing, we are not entirely helpless in the face of it.

Moreover, with effective screening, early disease can be detected, giving a far greater chance of survival. But the bottom line once cancer is there is access to effective treatment, without delay. As with other life-threatening diseases, the balance between prevention, screening and treatment is crucial. Breast cancer treatment has taken major steps forward in the past decade. Breast cancer rates are still rising, but deaths are falling in all the countries where mammography and high quality treatment are available and covered by affordable insurance or the public health system. The potential to reduce deaths from cervical cancer to low levels has been given a major boost with the advent of new technology appropriate for low-resource settings, but it will remain potential until the most affected countries’ health systems are strengthened and can put the new technology to work.

There are many specialist medical journals that cover all forms of cancer. The papers in this journal issue are not medical in focus. They are almost entirely about equity issues, programmatic issues, health systems issues, prevention and treatment, and personal experience. They show in the strongest possible way the importance of universal access to care for cancer for the poorest women in the world, as well as the rich.

More features

Highlights of the International AIDS Conference in Mexico in August 2008 are included in the Round Up section on HIV and AIDS in this issue. The non-theme section of the journal also has three papers about HIV – the need for couple-centred testing and counselling in sub-Saharan Africa, the role of support groups for HIV positive mothers in Viet Nam, and the importance of protection for the partners of men who have been circumcised for HIV prevention. Whether sex selection is influencing the sex ratio at birth in Viet Nam is the subject of another paper, and last but not least there is a paper on nurses developing a pregnancy-spacing intervention in a pronatalist Jewish community in Israel.

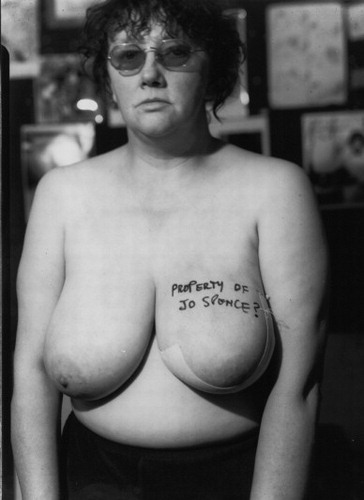

Property of Jo Spence: “Before I went into hospital in 1982 I decided I wanted a talisman to remind myself that I had some rights over my own body. Terry Dennett and I set up a series of tableaux, each with a different caption written on the breast. This is the one I took with me. I felt I was entering unknown territory and wanted to create my own magic fetish to take with me.” British photographer Jo Spence (1934-1992)

Notes

* Breast cancer is not technically considered a reproductive cancer, but I include it here. Breasts are for feeding infants, ergo, as I see it, they are part of the reproductive system. Breast cancer is in any case at epidemic proportions precisely because women are having later and fewer pregnancies and babies, and are breastfeeding less or not at all. According to Valerie Beral, who led the Million Women Study, a woman has a 7% decreased risk of breast cancer per birth and her risk drops by a further 4% for every year she has breastfed. Beral believes, however, that it should be possible to develop a hormonal treatment or vaccine to give the same level of protection to women who have not had large families.Citation1

References

- Boseley S. How 18th century nuns held clue to possible breast cancer cure. Guardian (UK), 6 October 2008.

- DM Parkin, F Bray. The burden of HPV-related cancers. Vaccine. 24(Suppl 3): 2006; S11–S25. Quoted in: English P. Human papillomavirus vaccination: glimpse into the black box of human papillomavirus vaccination. BMJ 2008;337:a1046.

- P Porter. “Westernizing” women’s risks? Breast cancer in lower-income countries. New England Journal of Medicine. 358(3): 2008; 213–216.

- Cervical cancer vaults to WHO priority list. Irin News, 22 September 2008.