Abstract

Due to a long-term shortage of obstetricians, the Ministry of Health of Senegal and Dakar University Obstetric Department agreed in 1998 to train district teams consisting of an anaesthetist, general practitioner and surgical assistant in emergency obstetric surgery. An evaluation of the policy was carried out in three districts in 2006, covering trends in rates of major obstetric interventions, outcomes in newborns and mothers, and the views of key informants, community members and final year medical students. From 2001 to 2006, 11 surgical teams were trained but only six were functioning in 2006. The current rate of training is not rapid enough to cover all districts by 2015. An increase in the rate of interventions was noted as soon as a team had been put in place, but unmet need persisted. Central decision-makers considered the policy more viable than training gynaecologists for district hospitals, but resistance from senior academic clinicians, a perceived lack of career progression among the doctors trained, and lack of programme coordination were obstacles. Practitioners felt the work was valuable, but complained of low additional pay and not being replaced during training. Communities appreciated that the services saved lives and money, but called for improved information and greater continuity of care.

Résumé

Face au manque d'obstétriciens à long terme, le Ministère sénégalais de la santé et le Département d'obstétrique de l'Université de Dakar ont convenu en 1998 de former des équipes de district composées d'un anesthésiste, d'un médecin généraliste et d'un assistant en chirurgie obstétricale d'urgence. En 2006, une évaluation de la politique a été menée dans trois districts pour analyser les tendances des principales interventions obstétricales, les résultats pour les nouveau-nés et les mères et les opinions des informateurs clés, des membres des communautés et des étudiants en dernière année de médecine. De 2001 à 2006, 11 équipes chirurgicales ont été formées mais six seulement fonctionnaient encore en 2006. Le rythme actuel de formation n'est pas assez rapide pour couvrir tous les districts d'ici à 2015. Une augmentation du taux d'interventions a été notée dès la mise en place d'une équipe, mais les besoins insatisfaits demeuraient. Pour les décideurs centraux, cette politique était plus viable que la formation de gynécologues pour les hôpitaux de district, mais elle se heurtait à la résistance des professeurs cliniciens, à un manque perçu de possibilités d'avancement pour les médecins formés et à une coordination insuffisante entre programmes. Les praticiens estimaient que le travail était utile, mais déploraient la faible rémunération complémentaire et regrettaient de ne pas être remplacés pendant la formation. Les communautés se félicitaient que les services sauvent des vies et économisent de l'argent, mais demandaient davantage d'information et une plus grande continuité des soins.

Resumen

Debido a la prolongada escasez de obstetras, el Ministerio de Salud de Senegal y el Departamento Obstétrico de la Universidad de Dakar acordaron, en 1998, capacitar a equipos distritales integrados por un anestesista, un médico general y un auxiliar quirúrgico en cirugía obstétrica de emergencia. En 2006, se realizó una evaluación de la política en tres distritos, donde se examinaron las tendencias en las tasas de intervenciones obstétricas importantes, los resultados en recién nacidos y madres, y los puntos de vista de informantes clave, miembros de la comunidad y estudiantes de medicina en su último año académico. Del 2000 al 2006, 11 equipos quirúrgicos fueron capacitados, pero sólo seis funcionaban en 2006. El ritmo actual de capacitación no es suficientemente rápido para abarcar todos los distritos al cabo del 2015. Se observó un aumento en el índice de intervenciones tan pronto se establecía un equipo, pero la necesidad insatisfecha persistió. Las autoridades decisorias centrales estimaron que esta política era más viable que capacitar ginecólogos en los hospitales distritales. Entre los obstáculos figuraban la resistencia de los médicos académicos sénior, la percibida falta de ascenso profesional entre los médicos capacitados y la falta de coordinación del programa. Los médicos estimaron el trabajo valioso, pero se quejaban de la baja paga adicional y de no ser sustituidos durante la capacitación. Las comunidades estaban agradecidas porque los servicios salvaron vidas y ahorraron dinero, pero solicitaron mejor información y mayor continuidad de servicios.

Senegal is a low-income West African country of about 12 million inhabitants. Half the population lives in urban areas, 25% in Dakar region. The fertility rate is 5.3 births per woman and the crude birth rate is 39.3%.Citation1 The GDP is around US$ 2,000 (using purchasing power parity)Citation2 and about half the population are still living below the poverty line, the majority in rural areas.Citation3

Antenatal care attendance is high, with an average of 87% of women (96% in urban areas) having at least one antenatal consultation. In urban areas, 81% of women deliver in a health facility, while in rural areas, the proportion is 45%.Citation1 The country is divided into 11 regions and 63 health districts, of which, outside Dakar, 18 provide comprehensive emergency obstetric care (EmOC) to about 4.4 million inhabitants, leaving 4 million others without a district hospital. In 2005, a fee exemption policy was introduced into five poorer regions, and in 2006 extended at regional hospital level to all regions apart from Dakar, the capital. The aim of the policy was to reduce financial barriers for maternal health services, increase supervised delivery rates and decrease maternal mortality.Citation4

Lack of basic surgical and emergency obstetric care in district hospitals in rural areas has long been a major problem in Senegal.Citation5 Practically all surgical cases in rural health districts (emergencies or not) were being referred to one of the ten tertiary-level regional hospitals. These patients faced many obstacles, including high transport costs. Usually they ended up going directly to the regional hospital – or a traditional healer. As a consequence, the tertiary hospitals were getting more patients than they could actually cope with. They suffered from infrastructural and material limitations, compounded by a chronic lack of qualified staff.Citation6 There was also no guarantee that emergency patients rushed by ambulance to Dakar would be promptly or adequately managed at the University hospital or any other national-level health establishment, for there again they confronted a plethora of problems – no bed space, not enough supplies, lack of blood transfusion services, lack of staff or operating theatres.Citation7Citation8

In the early 1990s, the Senegal Demographic and Health Survey found a maternal mortality ratio of 500–550 maternal deaths per 100,000 live births for the period 1979 to 1992.Citation9 In 1992, a situation analysis found low coverage for major obstetric interventions. Outside Dakar in 1992, there were only 12 hospitals with the capacity to perform a c-section and only 15 medical doctors skilled in doing c-sections.Citation10 The national caesarean section (c-section) rate averaged 0.7%, with the highest rate in Dakar (1.2%) and the lowest in poor rural areas (0.2%); of 100 women who underwent a c-section, 4.7% died and 30% of their newborns died.Citation11

A clear gradient of maternal mortality according to distance to a source of comprehensive essential obstetric careCitation12 called for a strategy of investment in building referral facilities and increasing the number of surgeons or obstetrician–gynaecologists. In 1996 the c-section rate was still only 0.6%.Citation8 The government decided in 1999 to ask the World Bank and African Development Fund to provide fellowships to train more obstetrician–gynaecologists under the National Health Development Plan. It was calculated that 130 surgically skilled people at district level were required to provide coverage of two per district outside Dakar. Yet only five gynaecologists per year ended up being trained, and very few agreed to work in regional hospitals.

This contributed to the Ministry of Health's decision in 1998 to delegate emergency obstetric surgery to non-specialists, which was perceived as the only possible alternative, and specifically to train anaesthetists, general practitioners and surgical assistants to provide emergency obstetric surgery at district level.

The task-shifting policy

Task shifting is a process of delegation of tasks to less specialised health workers.Citation13 The term comes from the domain of HIV/AIDS treatment and care, where it was recently developed as a policy response to the shortage of health workers.Citation14 The objective of task-shifting is to provide essential services closer to the population and hence to better meet their needs. To reduce maternal and neonatal mortality, an increase in rates of major obstetric interventions is required. To make this possible in many sub-Saharan African countries, the majority of c-sections are now performed by non-obstetricians, and in at least five countries by non-physician clinicians.Citation15

In Senegal, the Ministry of Health signed an agreement with the University and the university gynaecology & obstetrics department in 1998 to provide the training. The programme was supported by the African Development Fund in collaboration with the Cellule d'Appui et de Suivi of the Ministry of Health, which monitored implementation of the National Health Development Plan. The agreement provided for the training of eight district teams in 1998–2002 and eight more in 2005–2008. This would allow EmOC coverage of 16 of the 45 districts in Senegal by 2008, but it meant that it would take a further two decades to cover all 45 districts unless the rate was increased, and that is assuming all teams remained in place.

Anaesthetists in Senegal are qualified to perform general as well as spinal anaesthesia. Only one anaesthetist among the 11 teams trained between 2001 and 2006 undertook the specific training in obstetrics, since the others were considered to have acquired the requisite skills during their basic training. The general practitioners were trained in general obstetrics, post-abortion care, instrumental extraction, laparotomy for ectopic pregnancy and caesarean section for six months at the university hospital of Dakar and two months at the regional hospital level. On average these doctors performed 40 c-sections each under supervision. Surgical assistants, mostly recruited from among village health workers, who were auxiliary nurses, were trained in surgical assistance for three months at the university hospital in Dakar.

Study design

This article reports on an evaluation in 2006 of Senegal's task-shifting policy for emergency obstetric surgery. The districts of Bakel, Goudiri, both in Tambacounda region, and Koungheul (Kaolack region), were purposively selected for study, as they were the first districts to have trained teams. The evaluation covered trends in rates of major obstetric interventions, outcomes in newborns and mothers, and the views of key informants, community members and final year medical students. It analysed the factors that influenced the results and drew policy conclusions, both for Senegal and tentatively for other countries facing similar dilemmas.

We assessed retrospectively the effect of task shifting on the numbers, rates and maternal and perinatal outcomes of major obstetric surgical interventions in the district populations before and after the posting of teams trained in emergency obstetric surgery. Major obstetric interventions comprised caesarean section and laparotomy for ectopic pregnancy. All the hospitals where women from one of the three districts under study could have undergone an emergency obstetric intervention were investigated. In 2001, these were as follows. Goudiri had only one referral hospital that did c-sections, Tambacounda regional hospital, about 150 km from Goudiri city. Bakel had Bakel district hospital, Goudiri district hospital, Ourossogui regional hospital and Tambacounda regional hospital. Bakel women close to Goudiri went to Goudiri hospital and those close to Matam went to Ourossogui regional hospital. When Goudiri hospital was not functioning, women went or were sent to Tambacounda regional hospital. Koungheul had only Kaolack regional hospital, about 180 km from Koungheul city, which had a c-section rate of 0.1% in 2001.

Parallel to this, we interviewed decision-makers and health professionals, and organised discussions at community level. The objective of the interviews of the teams trained was to understand the difficulties and satisfactions they had experienced in their new roles and their views of the training. We also interviewed final-year medical students to ascertain their understanding of the task shifting policy and their willingness to be trained for these roles.

The workshops with community representatives were to obtain their perceptions of the task shifting policy, their satisfaction with the availability of the obstetric surgery team and its performance. The interviews with decision-makers at central level (Ministry of Health, WHO, UNFPA, senior academic clinicians) were to gather their perceptions of the task shifting policy in principle and in relation to its implementation, the obstacles to scaling up and ideas for improving access to emergency obstetric care.

Data collection and analysis

Data were collected from when the teams began working in 2001 up to June 2006, when the evaluation took place, except for Goudiri where we got data until the end of 2006. Data were collected on woman's district of residence, type of intervention, indication and maternal and baby outcomes. Data on interventions were collected from operating theatre and admission registers and hospital files in the district hospitals under study and in neighbouring hospitals, including the closest regional hospitals. In district hospitals, the small number of interventions and the careful documentation of cases by the surgical team give confidence that the data collection was complete. In regional hospitals, women were identified through the careful reading of maternity admission registers and then those coming from the district under study were investigated. EpiInfo6 was used for data entry and Excel for the calculation of rates.

Key informants were selected purposively for interviews, to represent the main stakeholders at national, regional and district level, and included a sample of trained team members. We interviewed 9 stakeholders at national level, 3 regional medical officers, 3 district medical officers, 4 trained medical officers, 5 anaesthetists and 5 surgical assistants. Interviews were semi-structured, with tested guidelines. We organised four focus group discussions with representatives of the community. The number of participants per focus group discussion never exceeded 12; criteria were availability at the time of the investigation, sex and age.

Finally, we organised a focus group discussion at the Faculty of Medicine (Le Dantec Hospital) with nine final-year students at the medical school to ascertain their willingness to be trained as emergency obstetric surgeons (including knowledge of the curriculum, career path and working conditions).

Qualitative data were recorded, transcribed and analysed manually and thematically, following the structure of questions posed to the informants.

Findings

Training and placement of surgical teams

The academic medical professionals did not favour task shifting, as they thought it would lead to sub-standard care; thus, they only accepted one training centre between 2001 and 2006, at the University of Dakar. This is the main reason why so few teams could be trained per year.

In the districts under study there is only one hospital, based in the capital city of the district. The obstetric surgical team that was sent to Bakel completed its training in July 2002, but only began work in September 2004. The team that was sent to Goudiri completed its training in August 2000, but only began work in April 2001. And the team that was sent to Koungheul completed its training in August 2000, but only began work in September 2001.

Long delays occurred between the end of training and opening of the operating theatres in these hospitals. Central decision-makers who were interviewed pointed out that this was due to lack of coordination of the different directorates (equipment and infrastructure, human resources) involved of the programme. Delays lasted 18.5 months on average, ranging from 4 months to as high as 45 months, either because the building had not been completed or did not conform to requirements, or equipment was lacking, or because one or more team members had not been posted. shows for each of the district teams the time and length of their training (hatched rectangles) and the time they opened their operating theatre (diamond). The arrows connect the end of the training with the beginning of surgical work, showing the delays between the posting of the teams and the opening of the theatres. Athe end of 2006, at the time of our data collection, Sokone and Gossas operating theatres were not opened. Kougheul stopped its surgical activities when the medical doctor suddenly died in 2005, and the operating theatre has not reopened yet. At the end of 2007, Kaffrine, Foundiougne and Velingara trained district teams had not yet started surgical work.

Utilisation of emergency obstetric surgery

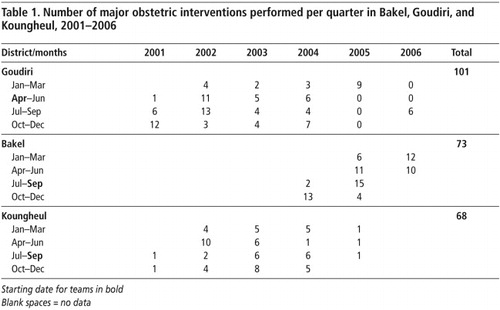

An increase in the rate of interventions occurred as soon as a team was put in place, but the number of interventions remained low in all three districts (Table 1). Almost all the interventions (99%) were caesarean sections (data not shown).

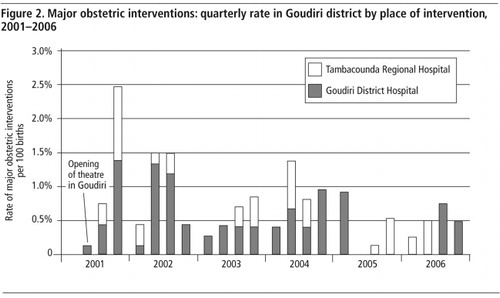

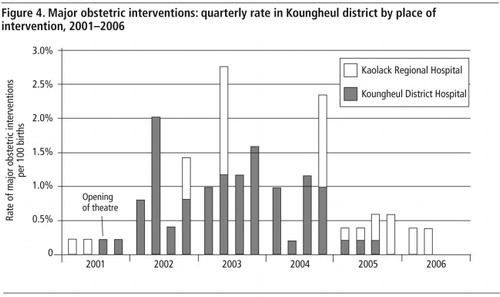

However, the numbers varied over time, depending on the availability of team members. – show the variation in each of the three districts. As soon as one member was absent for any reason (holidays, training or meeting outside the district), the rates dropped again, since recourse to the regional hospital did not necessarily take place if the unit in the district hospital stopped functioning. Hence, intervention rates remained lower than 1% on average. For example, when the Goudiri team suddenly stopped performing obstetric surgery in 2005 because the physician was on training, women had to go to Tambacounda regional hospital. However, only a few reached the regional hospital (5 in 2005 and 10 in 2006), keeping c-section rates below 0.5%.

In addition, the proportion of c-sections carried out for an indication which threatened the woman's lifeFootnote* was on average 47% (ranging from 37% to 62%, depending on the hospital). This is lower than the proportions usually observed in sub-Saharan Africa (61% on average; ranging from 51% to 70%).Citation16 This suggests that the c-sections being provided may not even have reached those most in need.

In the district of Bakel, the positive effect of supply was more marked than in the other two districts: intervention rates multiplied by 2.6 between 2001 and 2006 and the effect was clearly attributable to greater availability of surgery. However, just as in Goudiri, it was enough for one team member to be absent for an immediate drop in intervention rates to take place (e.g. see , fourth quarter, 2005).

After the opening of the theatre, rates progressively increased from 0.1% in 2001 up to 1.1% (including interventions performed in Kaolack) in 2003. After 2003, variations of the lower rate of c-sections were due to the absence of one of the team members until mid-2005, when the physician suddenly died and was not replaced.

Maternal and newborn outcomes

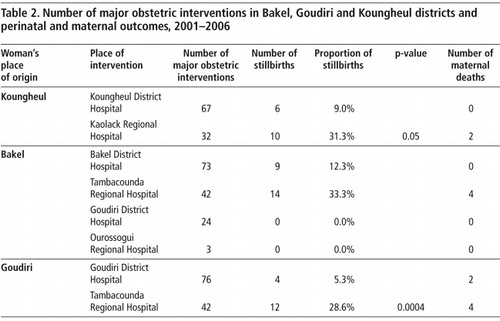

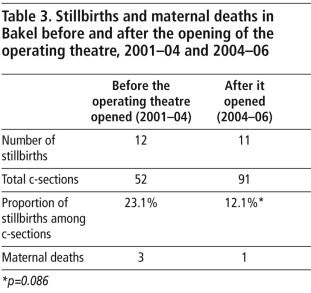

Only 12 maternal deaths were recorded in all the hospitals during the study period. Two occurred in Goudiri district hospital and 10 in the regional hospitals (Table 2). The number of maternal deaths was lower if the hospital with a surgical team was in the woman's district of residence (data not shown). This may be due to the women living closer to the hospital or to a selection bias (women in a serious condition are transferred to the regional hospital), but at least there was no excess of maternal deaths at district level. In Bakel, we compared the number of maternal hospital deaths before and after the opening of the theatre (Table 3). The number of maternal deaths decreased from 3 in 3.5 years, before the opening of the operating theatre, to 1 in 2 years with the theatre (not statistically significant). In parallel, the rate of major obstetric interventions per 100 births rose from 0.4% before to 1.4% after the opening of the theatre (p<0.00001). About half of the indications for surgery were to save the woman's life, i.e. six interventions per year before the opening of the theatre and 23 per year after the opening. Thus, in Bakel the benefit was clear. In the two other districts, we did not have a baseline to compare; however, the distribution of interventions per hospital suggests that the referral hospitals did not replace the district hospitals in meeting the obstetric needs.

In terms of newborn outcomes, the proportion of stillbirths among women who underwent a c-section was also lower when the caesarean delivery was performed in the woman's district of residence (Table 2). Bakel seems to be an exception, with no stillbirths when women underwent a c-section in Goudiri. However, those women who went to Goudiri probably lived closer to Goudiri district hospital than to Bakel's. In Bakel, the surgical team started to work in the third quarter of 2004 so there was a 3.5 year baseline to compare before and after the opening of the theatre. The proportion of stillbirths was almost halved (from 23.1 stillbirths per 100 c-sections in referral hospitals to 12.1% in all hospitals, including Bakel) after the opening of the operating theatre. However, this decrease is not statistically significant (Table 3).

Views of obstetric surgery team members

The general practitioners in the trained teams perceived a lack of career progression and felt they were undervalued during training, as young specialists could give them orders or were in competition with them to perform c-sections under supervision. In addition, during their training (an absence of at least eight months), they were not replaced in their districts, which increased the workload on their colleagues, who had remained in the district, and consequently reduced the availability and quality of care available. They also considered that the top-up to their salaries (50,000 FCFA or US$100 per month) was not enough because they often combined the functions of district medical officer and a doctor skilled in surgery. However, theyFootnote* saw advantages in this policy, especially for the public, who were benefiting from immediate and less expensive care compared to having to go to the regional hospital. They felt valued by the community and the families of patients as well and felt more useful.

Overall, the surgical assistants were the most satisfied with their roles. Originally, they had been community health personnel. Their training was short (three months), their bonus for taking on this responsibility reasonable (30,000 FCFA or US$60 a month) and outside of surgical interventions they continued to work as community health workers. Their main reward was public recognition and the pleasure of working in a team. In contrast, the anaesthetist technicians were the most disenchanted. The equipment in the units was often not as good as they expected; their bonus was not enough (35,000 FCFA or US$70 a month); but above all they did not get enough work – one c-section a week at the beginning and then often only one per month. Mostly they did nothing else because their only clinical skill was anaesthesia, so they were frightened that they would lose these skills through lack of practice.

Community views

The community representatives were satisfied with the quality of c-sections offered by the district hospitals. They experienced the financial benefit of having surgery locally (it saved referral costs and lodging and food for the family). But above all, the benefit was in lives saved, since in the rainy season the roads are sometimes impracticable and it is impossible to reach the regional hospital. On the other hand, they thought information could be improved, especially in rural areas. A large proportion of community members said communities were not well informed, or were only informed when a family member benefited from a c-section at the district hospital. Finally, community representatives complained that due to absences of team members, there were often periods when operations were not possible.

Views of medical students

All the medical students in the focus group discussion were concerned about the problem of maternal mortality in Senegal. Only one of them was aware that an eight-month training was offered in emergency obstetric surgery. In general, they were happy to be trained in obstetric surgery but thought it would be difficult for practical training to be included in their current curriculum, and that acquiring surgical skills would require supplementary training.

Discussion

Results showed a rapid increase in c-section rates as soon as a surgical team was functioning in the district hospitals, with positive outcomes for some newborns as well. However, these positive effects were jeopardised by the rise and fall in availability of surgical team members and was never sufficient to meet obstetric need.

Two limitations of the study were, first, that we collected retrospective data and cannot be sure we did not miss some c-sections at the regional hospitals. Second, it was not possible retrospectively to have a better indicator of quality of care than the proportion of stillbirths and the number of maternal deaths.

However, Senegal's programme of task shifting in emergency obstetric surgery up to 2006 was less than successful. Decision-makers officially favoured the task-shifting policy, but in practice did not take measures to make it a success, evidenced by long delays between completion of training and opening of operating theatres, a lack of information at the University, centralisation of the training to only one place, slow progress in scaling up, the absence of a career path and insufficient remuneration for the doctors, teams were not always functional, no replacements for team members were available when one or more were temporarily absent or no longer in post. Given that the anaesthetists involved, whose initial training was broader than obstetric surgery, had no other work to do except a few obstetric interventions per month, the cost-effectiveness and ethics of focusing only on obstetric surgery must also be raised.

Despite the concern that it would lead to sub-standard quality of care on the part of some prominent senior medical staff at the university, there is long-standing international evidence that over 75% of surgical procedures performed even at tertiary hospitals in most developing countries are of a low level of complexity and do not require fully-trained surgeons and obstetricians.Citation17Citation18 It has also been demonstrated in countries such as Indonesia, Ethiopia, Sudan and the Democratic Republic of Congo that the majority of these procedures can be carried out successfully and with little complication by adequately trained general practitionersCitation19–21 and also by non-physician health care providers.Citation22–25 Several comparative studies pertaining to delegation of skills and responsibilities in the areas of surgery and obstetrics in developed countries (Canada) as well as developing countries (Mozambique and Malawi) have shown no significant difference in quality or safety of clinical outcomes between care provided by specialists and that of non-specialists.Citation26–28

The literature describes this form of resistance as being fuelled by concern over loss of potential earnings and the need to maintain rigid boundaries around professional turf, as well as the belief that it will be detrimental to population health.Citation25,29–31. The failure of a district surgery training programme in Ethiopia, which consisted of “intra-cadre delegation”, whereby clinical functions were shifted from specialised general practitioners to less specialised ones,Citation32 was attributed in part to specialists' reluctance to supervise the trained general practitioners in the follow-up phase of the programme.Citation22 In Mozambique, however, population needs and political commitment have overridden professional resistance and given way to fruitful collaboration, after initially hostile attitudes towards non-doctors performing surgery.Citation33Citation34 The understanding that specialists and generalist doctors are not being replaced by surgical technicians and the notion of sharing skillsCitation35, instead of relinquishing them to others, may have been instrumental in this change of attitudes and perceptions.Citation36

In Senegal, the pace of training has been so slow (six functioning teams out of 11 trained in six years) when the need is so great (90 teams required for 45 districts without a surgical facility), that it will take 20 years more to cover all 45 districts with only one team at the current rate.

Moreover, limiting surgery to the few c-sections and laparotomy for ectopic pregnancies necessarily means a very low level of surgical activity. Indeed, in the district populations under study (between 780 and 1,330 expected births per district in 2006)Citation37 we can expect a maximum of 1.3 c-sections per week if the hospital can reach the WHO norm of 5% of deliveriesCitation38 and one c-section every two weeks in the best current conditions of a 2% c-section rate (e.g. third quarter of 2005 in Bakel, ). This is not enough to maintain the skills and motivation of the personnel if they do not perform other surgical interventions. Maintaining a full surgical team (surgical assistant, anaesthetist, physician) and equipment for an average of 17–36 operations per year is also not very efficient or cost-effective. There is a growing consensus that what has recently begun to be called Emergency & Essential Surgical CareCitation39Citation40 should be provided in district hospitals in low-income countries, to reduce all kinds of mortality and morbidity, and different groups are working in this direction.Citation41–43

In Senegal, to implement a task shifting policy and cover its rural population before 2015, policy-makers must not only speed up the pace of the programme but should also work toward a shift from district obstetrics alone to more comprehensive provision of emergency and essential district surgery. Accelerating the pace of training requires the clear involvement of the government and support from universities and professional associations, which is not the case to date. In addition, the intervention needs to include rapid implementation strategies when training is completed and robust support from health managers to ensure that teams are effective and retained.

Acknowledgements

This work was undertaken as part of an international research programme Immpact (<www.abdn.ac.uk/immpact>), funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, the Department for International Development, the European Commission and USAID. The funders are not responsible for the information provided or views expressed in this paper. The views are solely those of the authors. The study was made possible by UNFPA, which supported the Senegalese research team. We are particularly grateful to Dr Isabelle Moreira, UNFPA, who contributed to the implementation of the study. Thanks are also due to the Reproductive Health Division, Ministry of Health, Senegal, which provided appropriate support.

Notes

* Brow presentation, transverse lie, cephalopelvic disproportion, antepartum haemorrhage due to placenta praevia, abruptio placentae.

* An official district medical officer, who is paid at least 50,000 FCFA as a bonus, does not have the additional work or responsibility of surgery.

References

- Ndiaye S, Ayad M. Enquête Démographique et de Santé (EDSIV), Sénégal 2005. Dakar: Ministère de la Santé et de la Prévention Médicale, Centre de Recherche pour le Développement Humain & Calverton: ORC Macro, 2006.

- The Economist Intelligence Unit, Senegal country outlook. At: <www.alacrastore.com/country-snapshot/Senegal. >. Accessed 12 August 2008.

- ESAM II. Rapport de synthèse de la deuxième enquête sénégalaise auprès des ménages (ESAM II). 2004; Ministère de l'Economie et des Finances: Dakar.

- S Witter, M Armar-Klemesu, T Dieng. National fee exemption schemes for deliveries: comparing the recent experiences of Ghana and Senegal. F Richard, S Witter, V De Brouwere. Reducing the Financial Barriers to Access to Obstetric Care. Studies in Health Services Organisation and Policy Series. 2008; ITG Press: Antwerp.

- Ministère de la santé et de la prévention médicale. Feuille de route multisectorielle pour accélérer la réduction de la mortalité et de la morbidité maternelles et néonatales au Sénégal. 2006; Ministère de la santé et de la prévention médicale: Dakar.

- CT Touré, M Dieng. Urgences en milieu tropical: état des lieux. L'exemple des urgences chirurgicales au Sénégal. Médecine Tropicale. 62: 2002; 237–241.

- E Denerville, G Kegels, E Lodi. Contribution du suivi-scientifique du projet aux travaux du comité de pilotage des réflexions autour de l'offre de soins chirurgicaux dans les districts sanitaires du Sénégal. Projet ASSMRKF. March. 2008; Institute of Tropical Medicine: Antwerpen.

- CT Cissé, EO Faye, L de Bernis. Césariennes au Sénégal: couverture des besoins et qualité des services. Cahiers Santé. 8: 1998; 369–377.

- Ndiaye S, Diouf PB, Ayad M. Enquête Démographique et de Santé (EDSII), Sénégal 1992/93. Dakar: Ministère de la Santé & Calverton: ORC Macro, 1994.

- O Faye El Hadj, A Dumont, I Toure Diop. Troisième enquête nationale sur la couverture obstétrico-chirurgicale au Sénégal. 2003; Ministère de la santé du Sénégal, OMS, Ambassade de France, CHU Le Dantec: Dakar.

- D Bouillin, G Fournier, A Gueye. Surveillance épidémiologique et couverture chirurgicale des dystocies obstétricales au Sénégal. Cahier santé. 4: 1994; 399–406.

- B Kodio, L de Bernis, M Ba. Levels and causes of maternal mortality in Senegal. Tropical Medicine & International Health. 7(6): 2002; 499–505.

- WHO, PEPFAR, UNAIDS. Task shifting: rational redistribution of tasks among health workforce teams: global recommendations and guidelines. 2008; WHO: Geneva.

- B Samb, F Celletti, J Holloway. Task shifting: an emergency response to the health workforce crisis in the era of HIV. Lessons from the past, current practice and thinking. New England Journal of Medicine. 357: 2007; 24.

- F Mullan, S Frehywot. Non-physician clinicians in 47 sub-Saharan African countries. Lancet. 2007. June 14. DOI: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60785-5.

- UON Network. L'approche des besoins obstétricaux non couverts pour les interventions obstétricales majeures. Etude comparative Bénin, Burkina Faso, Haïti, Mali, Maroc, Niger, Pakistan, Tanzanie. 2000. At: <www.itg.be/uonn/pdf/ENGINTC00.PDF. >. Accessed 10 July 2007.

- A Velez-Gil, MT Galarza, R Guerrero. Surgeons and operating rooms: underutilized resources. American Journal of Public Health. 73: 1983; 1361–1365.

- D Watters, A Bayleys. Training doctors to meet the surgical needs of Africa. British Medical Journal. 295: 1987; 761–763.

- J Thouw. Delegation of obstetric care in Indonesia. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics. 38(Suppl): 1992; S45–S47.

- A Loutfi, AP McLean, J Pickering. Training general practitioners in surgical and obstetrical emergencies in Ethiopia. Tropical Doctor. 25(Suppl 1): 1995; 22–26.

- G Meo, D Andreone, U De Bonis. Rural surgery in southern Sudan. World Journal of Surgery. 30: 2006; 495–504. DOI: 10.1007/s00268-005-0093.

- SM White, RG Thorpe, D Maine. Emergency obstetric surgery performed by nurses in Zaire. Lancet. 2: 1987; 612–613.

- F Vaz, S Bergström, M Vaz. Training medical assistants for surgery. Bulletin of WHO. 77: 1999; 688–691.

- S Bergström. Who will do the caesareans when there is no doctor? Finding creative solutions to the human resource crisis. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 112(9): 2005; 1168–1169.

- M Vaz, S Bergstrom. Mozambique – delegation of responsibility in the area of maternal care. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics. 38(Suppl S37): 1992; 9–39.

- E Krikke, N Bell. Relation of family physician or specialist care to obstetric interventions and outcomes in patients at low risk: a western Canadian cohort study. Canadian Medical Association Journal. 140: 1989; 637–643.

- G Chipolora, C Pereira, F Kamwendo. Postoperative outcome of caesarean sections and other major emergency obstetric surgery by clinical officers and medical officers in Malawi. Human Resources for Health. 5: 2007; 17. DOI: 10.1186/1478-449-5-17.

- C Pereira, A Bugalho, S Bergström. A comparative study of cesarean deliveries by assistant medical officers and obstetricians in Mozambique. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 103: 1996; 508–512.

- I Loefler. Who will do the caesarean where there is no doctor?. [Letter] British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 113(1): 2006; 127.

- I Loefler. Surgery in the third world. Baillière's Clinical Tropical Medicine and Communicable Diseases. 3(2): 1988; 173–189.

- G Rooth, E Kessel. Foreword: Delegation of responsibilities in maternity care in developing countries: proceedings of a workshop in Singapore, 8–10 September 1991. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics. 38(Suppl): 1992; 1–2.

- D Dovlo. Using mid-level cadres as substitutes for internationally mobile health professionals in Africa. A desk review. Human Resources for Health. 2: 2004; 7.

- Bergström S. Issue paper on maternal health care. Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (SIDA). Health Division Document 1998:1.

- PI Garrido. Training of medical assistants in Mozambique for surgery in rural settings. South African Journal of Surgery. 35: 1997; 144–145.

- A Hopkins, J Solomon, J Abelson. Shifting boundaries in professional care. Journal of Royal Society of Medicine. 89: 1996; 364–371.

- A Cumbi, C Pereira, R Malalane. Major surgery delegation to mid-level health practitioners in Mozambique: health professionals' perceptions. Human Resources for Health. 5: 2007; 27.

- Agence Nationale de la Statistique et de la Démographie. Résultats du troisième recensement général de la population et de l'habitat – (2002). Rapport final de présentation des résultats. 2006; ANSD: Dakar.

- UNICEF, WHO, UNFPA. Guidelines for monitoring the availability and use of obstetric services. 1997; United Nations Children Fund: New York.

- World Health Organization. Surgical care at the district level. 2003; WHO: Geneva.

- World Health Organization. WHO meeting towards a global initiative for emergency and essential surgical care (GIEESC), 8–9 December 2005. 2005; WHO: Geneva.

- D Ozgediz, D Jamison, M Cherian. The burden of surgical conditions and access to surgical care in low- and middle-income countries. Bulletin of WHO. 86: 2008; 646–647.

- H Debas, R Gosselin, C McCord. Surgery. Chapter 67. D Jamison. Disease Control Priorities in Developing Countries. 2nd ed., 2006; Oxford University Press: New York, 1245–1259.

- D Spiegel, R Gosselin. Surgical services in low- and middle-income countries. Lancet. 370: 2007; 1013–1014.