Abstract

The migration of doctors and nurses from low- to high-income countries has left many countries relying on mid-level cadres as the mainstay of their health delivery system, Malawi being an example. Although an extremely important resource, little attention has been paid to the management and further development of these cadres. In this paper we use the concept of organisational justice – fairness of treatment, procedures and communication on the part of managers – to explore through a questionnaire how mid-level cadres in jobs traditionally done by higher-level cadres self-assessed their level of job satisfaction. All mid-level health workers present on the day of data collection in 34 health facilities in three health districts of Malawi, one district each from the three geographical regions, were invited to participate; 126 agreed. Perceptions of justice correlated strongly with level of job satisfaction, and in particular perceptions of how well they were treated by their managers and the extent to which they were informed about decisions and changes. Pay was not the only important element in job satisfaction; promotion opportunities and satisfaction with current work assignments were also significant. These findings highlight the important role that managers can play in the motivation, career development and performance of mid-level health workers.

Résumé

La migration de médecins et d'infirmières de pays pauvres vers des pays à revenu élevé oblige beaucoup de pays, dont le Malawi, à s'appuyer sur des cadres moyens comme pivot de leur système de santé. Bien qu'il s'agisse d'une ressource extrêmement importante, la gestion et le développement ultérieur de ces cadres n'ont guère reçu d'attention. Dans cet article, nous utilisons le concept de justice organisationnelle – traitement, procédures et communications équitables de la part des superviseurs – pour étudier au moyen d'un questionnaire comment les cadres moyens occupant des emplois traditionnellement dévolus aux cadres supérieurs évaluent leur satisfaction professionnelle. Tous les soignants de niveau intermédiaire présents le jour du recueil des données dans 34 établissements de santé du Malawi, sélectionnés dans un district pour chacune des trois régions géographiques, ont été invités à participer; 126 ont accepté. La manière de concevoir la justice était fortement corrélée avec le niveau de satisfaction professionnelle, en particulier dans quelle mesure les cadres moyens estimaient être bien traités par leur superviseur et être informés des décisions et des changements. Le salaire n'était pas le seul élément déterminant: les possibilités d'avancement et la satisfaction quant aux tâches professionnelles actuelles avaient aussi une influence. Ces conclusions soulignent le rôle important que les superviseurs peuvent jouer dans la motivation, les perspectives de carrière et les performances des soignants de niveau intermédiaire.

Resumen

Debido a la emigración de médicos y enfermeras de países de bajos ingresos a países de altos ingresos, muchos países, como Malaui, tienen que depender de los prestadores de servicios de nivel intermedio como el pilar del sistema de salud. Aunque son un recurso sumamente importante, no se ha prestado mucha atención al manejo y desarrollo de este grupo de profesionales. En este artículo se utiliza el concepto de justicia organizacional – en el trato, los procedimientos y la comunicación por parte de los administradores – para explorar mediante un cuestionario cómo los profesionales de nivel intermedio en trabajos realizados tradicionalmente por profesionales de nivel superior autoevaluaron su nivel de satisfacción laboral. Se invitó a participar a todos los trabajadores de salud de nivel intermedio presentes el día de la recolección de datos en 34 establecimientos de salud, en tres distritos de salud de Malaui, uno de cada región geográfica; 126 accedieron. Las percepciones de justicia estaban muy correlacionadas con el nivel de satisfacción laboral, en particular las percepciones de cuán bien eran tratados por sus supervisores y hasta qué grado se les informaba sobre las decisiones y los cambios. La paga no era el único elemento importante en la satisfacción laboral; las oportunidades de ascenso y la satisfacción con las asignaciones laborales también eran significativas. Estos hallazgos resaltan el importante papel que pueden desempeñar los administradores en la motivación, el desarrollo profesional y el desempeño de los trabajadores de salud de nivel intermedio.

The human resources crisis has severely impacted on the health systems of many African countries, creating high vacancy rates for almost all cadres of health workers. Malawi has been particularly affected, with latest figures showing vacancy rates of 77% for specialist doctors, 45% for medical officers, 80% for nursing officers and 44% for nursing sisters.Citation1 However, Malawi has a history of employing cadres of health workers with shorter periods of training, for example, enrolled nurse-midwives, clinical officers and medical assistants, who have become the mainstay of the health delivery system. Staffing figures for the districts, for example, show that whilst there were a total of 872 enrolled nurse-midwives employed in 2006, only 127 registered nurses were in post. Likewise there were 232 clinical officers and 300 medical assistants but only 16 medical officers.Citation2 In the process, much of the obstetric work traditionally carried out by doctors has been shifted to clinical officers, who perform as much as 93% of major emergency obstetric operations in government hospitals and 78% in mission facilities, with comparable post-operative outcomes.Citation3Citation4

Despite these successes, most of the attention in addressing the human resource crisis has focused on increasing the capacity of training institutions to produce more doctors and registered nurses to fill vacancies. In addition there is an assumption that cadres such as enrolled nurses, clinical officers and medical assistants are somehow non-poachable, because they lack internationally recognised qualifications.

The human resource crisis is also due to considerable in-country migration between the public and private health sectors, including to internationally funded programmes that pay higher salaries, between urban and rural areas, and between tertiary and primary health care. Increasing health worker migration into private, urban, tertiary facilities is undermining provision of appropriate public, rural, primary care. In countries that do have enough doctors, while there may be a 1:500 doctor–patient ratio in the city, remote districts suffer from a 1:100,000 ratio.Citation5 African doctors, nurses, pharmacists and medical technicians prefer to work in urban hospital settings where professional camaraderie is readily available and promotion more probable. The availability of good housing, schooling for their children and leisure is also an important consideration. The urban location of most hospitals makes it inevitable that health workers mostly work in the cities.Citation6 In Ghana, Guinea and Senegal, more than 50% of physicians are concentrated in the capital, where less than 20% of the population live.Citation7 In the capital region of Chad in 2002, there were 71 doctors per 100,000 people, while in the Charai-Baguirmi region the ratio was 2:100,000.Citation8 In Ghana, 55% of pharmacists are in the Greater Accra region, which has 16% of the population and 2% in the Northern region, with 10% of the population.Citation7

With 31 countries failing to meet the “Health for All” standard of one doctor per 5,000 people,Citation9 alternative models of service delivery need to be explored, along with greater efforts to understand and reverse health worker outflows from areas where they are desperately needed.

Among its considerable attempts to address the human resources crisis, Malawi developed a Six-Year Emergency Training Plan for health workersCitation10 and an Emergency Human Resources Programme,Citation11 aimed at improving staff recruitment and retention through salary top-ups and increased training. In 2005 the government introduced a 52% salary top-up which, combined with further increases, made health workers the highest paid civil servants. Additional incentives took the form of rural allowances, housing and transport, based on the premise that increased remuneration and benefits retain people in their jobs.Citation12Citation13 Yet research demonstrates that salary is not the only or most important factor influencing retention.Citation14 Maternal health nurses, for example, ranked improved working environments and conditions (such as good facility management and adequate equipment) as high as or higher than financial incentives in one study.Citation15

Most African countries have focused on producing more expensive (less cost-effective) cadres of health workers relative to their disease burden and to what they can afford. Some experts have pointed out that as much as two-thirds of Africa's disease burden could be addressed by community health nurses. Malawi's government, with strong urging from the nurses and midwifery council, abolished the enrolled nursing programme in the early 1990s to focus on professional nurses. Education/training of enrolled and auxiliary nurses was also banned in Zambia and Ghana. By 1998 the nursing shortage in Malawi had reached crisis point and the decision was rescinded. Enrolled nurses are now being trained as part of the Emergency Pre-Service Training Programme (2001) (Phoya A. Personal communication, Lilongwe, 2008). The Christian Health Association of Malawi continues to receive government funding for the training of enrolled nurses, and cites this as one of the reasons its health facilities are better staffed than the public facilities (Mukiwa R. Personal communication, Lilongwe, 2006).

Studies addressing the perceptions of these mid-level cadres and the factors that influence their motivation, performance and retention within health care systems are scarce.Citation16 However, recent research indicates that these cadres are becoming demotivated due to poor career development and promotion prospects, and lack of positive supervision, feedback and recognition, which leave them feeling unsupported and undervalued.Citation17Citation18 There is concern that quality of care will suffer if they are not properly supported and motivated.Citation16,18–21

One concept that connects how employees are treated with motivation and job satisfaction is that of organisational justice,Citation22 which generally encompasses three components: distributive justice, procedural justice and interactional justice.Citation23 Distributive justice refers to how fairly employees feel they are treated (in comparison to others) with regards to the distribution of resources and outcomes.Citation23Citation24 Does the person think they are getting the workload, work schedule, salary level, promotion and allowances they deserve? Do they perceive that outcomes are fair, e.g. that their opportunities for further training are fair in comparison to those afforded their colleagues? Procedural justice is the perceived consistency and fairness of procedures that are used,Citation25 e.g. how employees are selected for training, or how decisions are taken about which employees deserve promotion. Interactional justice relates to the dignity and respect afforded individuals in interpersonal communication relating to organisational procedures.Citation23

Two meta-analyses of mainly US studiesCitation26Citation27 showed that greater perceived organisational justice was associated with higher satisfaction, greater commitment to the workplace and more extra-role behaviour. Paying attention to justice therefore seems important to improving performance and retention of health workers. In this study, carried out in March to May 2007, we utilised the concept of organisational justice to explore the relationship between how enrolled nurses, clinical officers and medical assistants felt they were being treated by their managers and the impact on their workplace behaviour and job satisfaction.

Sampling and methods

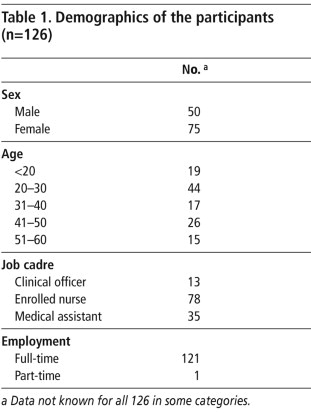

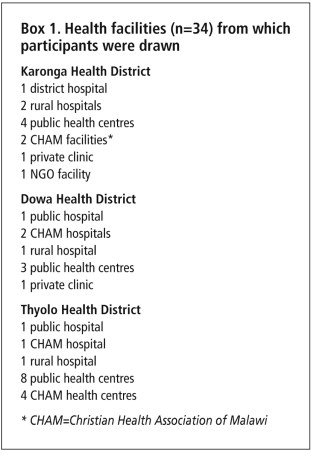

All health facilitiesCitation34 in three districts in Malawi (one from each of the three geographical regions) were included in the sampling frame. The sample consisted of those willing to participate at the time the data collectors visited the facilities (Box 1). This paper analyses their responses. Of 374 health workers invited to participate, 153 agreed (response rate 41%), of whom 126 were mid-level providers – clinical officers, medical assistants and enrolled nurses – performing tasks traditionally undertaken by doctors and registered nurses/midwives. Although data were also collected from registered nurses, these were excluded from the analysis as we did not examine whether they did tasks traditionally performed by doctors. Data collected on work environment are reported elsewhere.Citation21 The majority of the participants were under 35 years of age and in full-time permanent health service employment (Table 1).

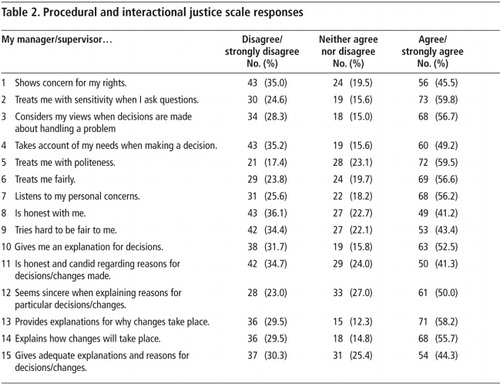

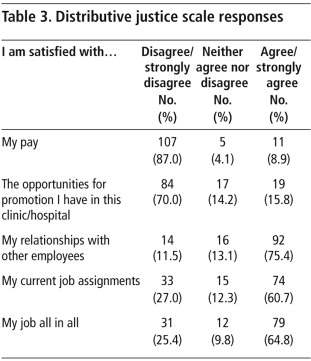

Organisational justice was measured using Niehoff & Moorman's justice scale,Citation28 a five-point likert-type scale that measures attitudes on distributive, procedural and interactional justice along a continuum from strongly disagree to strongly agree. Distributive justice was measured using five items (Table 3) assessing the fairness of different work outcomes, including pay, workload, work schedule and job responsibilities. Procedural justice was measured in relation to formal procedures and interactions. Six formal items (Table 2, items 10–15) measured the degree to which employees felt their opinion was considered when decisions were made. Nine interactional items (Table 2, items 1–9) measured the degree to which employees felt their needs were considered and adequate explanations given for decisions. Reported reliabilities for this scale were above 0.90 for all three dimensions of justice.Citation29

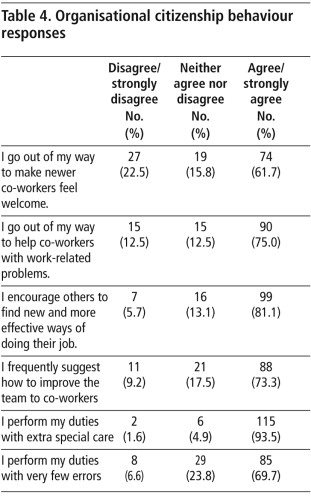

Workplace behaviour was measured using a five-dimension organisational citizenship behaviour scale developed by Podsakoff & McKenzie,Citation30 which measures being helpful and conscientious and performing duties beyond those normally expected and generally improving aspects of the job.Citation28,31,32 The model identifies five dimensions of citizenship behaviour that emerged with reported reliabilities over 0.70 for each dimension.Citation28

Job satisfaction was explored through several items with scaled responses. None of the job satisfaction scales in the extant literature covered intention to leave and perceived likelihood of finding another job. The items used were identified from existing questionnaires, relevant literature and suggestions from researchers and policymakers with expertise in the area. A likert scale ranging from strongly disagree (assigned a numeric value of 1) to strongly agree (assigned a numeric value of 5) was used to measure responses to each item. All analysis was carried out using SPSS 16.0. (Further details of the methodology can be obtained from the corresponding author.)

Findings

Procedural and interactional justice and job satisfaction

The first nine items on the scale measured interactional justice. Staff were divided on whether their managers showed concern for their rights, with slightly more agreeing than disagreeing with the statement. However, for items 2–7 measuring perceptions of interactions with managers, almost twice as many of the health workers agreed as disagreed that their managers showed consideration and sensitivity when dealing with them (Table 2). One-quarter to one-third of health workers surveyed did not believe their managers showed consideration and sensitivity when dealing with them. Interestingly, the results were very different for items 8–9, which were concerned with the honesty and fairness of their managers; they were more divided in their opinions, with only slightly more agreeing than disagreeing. Item 11, on procedure rather than interaction, is also about the honesty of managers and showed a similar response. By contrast staff were more positive about managers providing explanations for decisions or explanations for changes to work practices.

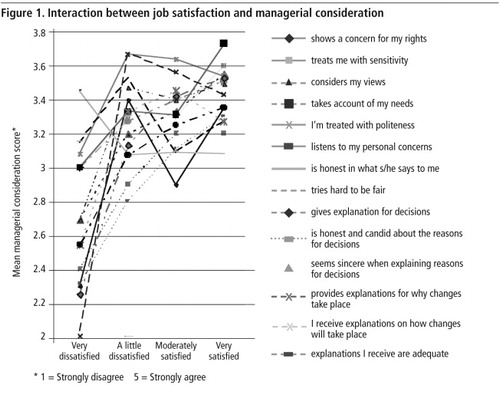

Principal components analysis found that one factor explained 45% of the variation in responses. This factor (comprising eight items) was “managerial consideration” and reflected a considerate, caring and respectful style of interaction between managers and others. Two other components emerged which accounted for 10% and 8% of the variance, but because of the higher predictive power of “managerial consideration”, we will focus only on it when exploring the relationship with job satisfaction.

shows how perceptions of justice or fairness interacted with job satisfaction, with mean scores for the eight aspects of “managerial consideration” plotted against degree of job satisfaction. The increasing mean scores moving from “very dissatisfied” to “very satisfied” show evidence of a positive relationship between justice and reported levels of job satisfaction for almost all items on the procedural justice scale. The more considerate the health workers believe their manager/supervisor is, the more they are likely to be satisfied in their job. This effect is strongest for the item “my manager considers my views” and the item “my manager is honest and candid about the reasons for decisions”. The steep rise in the graph for almost all items, from “very dissatisfied” to “a little dissatisfied” scores for job satisfaction, are an indication that how they were treated by their manager played a critical role in the degree of dissatisfaction experienced.

The two items that relate to honesty show interesting differences. Having a manager who is honest and candid about the reasons for decisions is likely to lead to greater job satisfaction, whereas honesty generally in the manager seems to be less important to health workers. The other six items related to “managerial consideration” concerned the degree to which the manager takes the needs, concerns and views of the employee into account, all examples of interactional justice.

Distributive justice and job satisfaction

Table 3 shows the extent of satisfaction with pay, workload, opportunity for promotion, work schedule and job responsibilities from the distributive justice scale. The highest levels of disagreement were to do with satisfaction with their pay (107 people disagreed or strongly disagreed) and with promotion opportunities (84 disagreed or strongly disagreed). The highest levels of satisfaction were to do with relationships with colleagues (92 agreed or strongly agreed). More than half agreed that all in all they were satisfied with their job, though dissatisfaction with pay and promotion show the danger of taking this at face value.

Exploring responses on the distributive justice scale in more depth gives a better understanding of which particular components of the job accounted for feelings of dissatisfaction amongst staff. plots the mean scores across the sample for each of these items against responses on the job satisfaction scale (very dissatisfied to very satisfied). Satisfaction with the job was positively correlated with satisfaction with pay (Pearson r=0.222; p<.05), promotion (Pearson r=0.232; p<.05) and current assignments (Pearson r=0.313; p<.01). However, satisfaction with current assignments was more strongly correlated with job satisfaction than the other two items.

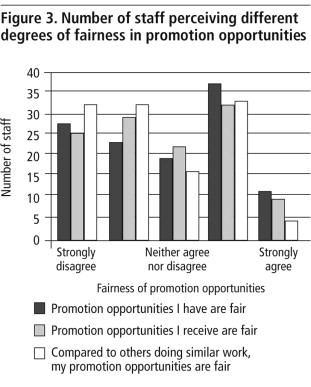

Staff were asked to indicate the extent to which they agreed or disagreed with three statements on promotion, as shown in . Again satisfaction with the job was strongly correlated with “the promotion opportunities I have are fair” (Pearson r=0.287; p<.01); “the opportunities I receive are fair” (Pearson r=0.319; p<.01); and “compared to others doing similar work, my opportunities for promotion are fair” (Pearson r=0.257; p<.01). Interestingly, the greatest number of staff disagreed with the statement “compared to others doing similar work, my opportunities for promotion are fair”. It is the comparison with others that leads to a sense of being treated unfairly, suggesting inequity in the distribution of promotion opportunities rather than a lack of opportunites per se.

Workplace behaviour

The organisational citizenship behaviour scale, which measures being helpful and conscientious and doing more than is normally expected, found that the majority of participants had positive perceptions of their own behaviours. The statement that had the highest levels of disagreement (Table 4) was “I go out of my way to make newer co-workers feel welcome” (27 staff disagreed or strongly disagreed). The number of staff agreeing that they helped co-workers was much higher than the number who agreed that they made newer co-workers feel welcome, suggesting that they act out of professional obligation to their work rather than any sense of camaraderie.

Discussion

Perceptions of justice correlated strongly with level of job satisfaction, and in particular perceptions of how well mid-level providers were treated by their managers and the extent to which they were informed about decisions. Pay was not the only important element in job satisfaction; promotion opportunities and satisfaction with current work assignments were also significantly correlated with job satisfaction. Interestingly, the strongest correlation with job satisfaction on the distributive justice scale occurred with “satisfaction with current work assignments”. The fact that mid-level providers who were satisfied with their job assignments were also reporting high levels of job satisfaction provides some evidence that task shifting is not only working in terms of maintaining quality of service,Citation3Citation4 but is also having a positive effect on health worker motivation.

Although the research team invited all staff on duty in the facilities selected to take part, some 60% declined. While the results may or may not be biased, depending on the views of those who refused to participate, the spread of scores across the job satisfaction scales would suggest that this was not the case. While we cannot draw conclusions about job satisfaction among mid-level providers as a whole, as our focus was on factors influencing job satisfaction, this is less of a concern.

Distributive justice is often associated with perceptions of fair outcome for fair effort or input. However, our data show that when distributive justice is measured in terms of fair outcome for these health workers in comparison with others doing similar work, the effect is heightened. This is a particularly important finding in the health care context and culture in Malawi, as elsewhere, where inter-professional rivalry is a strong feature. Dovlo argues that as mid-level cadres have developed, and as delegation of tasks has been accompanied by delegation of responsibility, “initial hostility changed to fruitful collaboration and to mutual recognition of new professional turfs”.Citation16 This has not always been the case in Malawi, however, as found in two previous studies, one of mid-level providers working in maternal and obstetric careCitation18 and another of mid-level providers' work environment.Citation21 In the former, tensions between clinical officers and doctors were found, and in the latter, which was conducted with the same sample as this study, nursing cadres expressed more job satisfaction than clinical officers and medical assistants, who reported poorer working relationships.

Our findings emphasise the important contribution of managers to improving the motivation and performance of mid-level health workers. Other studies have also found that procedural justice was related to job attitudes,Citation25,33,34 including organisational commitment and trust in management and that inadequate management support and a sense of not being valued by their managers were strong features of the environment. Yet the role of managers in motivating and retaining staff is something that has largely been ignored in attempts to address the migration of health workers, even though managers who are unsupportive or inconsiderate can be a strong push factor.Citation21 Improving the attitudes of managers towards health workers is a relatively inexpensive approach that could have a significant impact on performance and retention.

Conventional research shows significant positive links between all dimensions of justice and performance or organisational outcomes.Citation29Citation35 If staff feel they are being treated fairly and justly, they are likely to perform better. If they are treated unfairly they will try to restore justice by holding back performance.Citation36 However, the majority of health workers in our study agreed that they were engaged in citizenship behaviours, especially on items such as performing their duties with special care and helping co-workers solve problems. The lower number claiming they went out of their way to “make newer co-workers feel welcome” may indicate tensions between themselves (many of whom have many years of experience) and newly recruited doctors and nurses (with little or no practical experience). However, further research would be needed to confirm this. Our study used self-assessment measures of performance and extra-role behaviour. An independent assessment of performance might paint a different picture.

Penn-Kekana et alCitation37 make the point that context shapes how local health systems operate and stress the importance of interaction between human actors. The resource-poor context and poor salaries in the Malawian health system could be expected to affect responses and may be different to those found in high-income settings. Apart from resource variations, managerial attitudes towards employees can also vary by context. This study provides evidence for the critical role that interaction between health workers and their managers play in job satisfaction. We believe that that may also ultimately affect retention. Developing national strategies and incentive packages, as has been done by the Malawian government, is one step towards addressing the human resources crisis. However, without the right conditions and positive workplace relationships, whether these will have sufficient effect remains to be shown. Penn-Kekana et al argue that:

“…the development of programmes and policy that improve outcomes for users therefore requires direct engagement with context and with how formal organisational structures, intended incentives and management procedures interact with informal structures, behaviours and relationships on the ground.” Citation37

This is particularly important in improving maternity care in Malawi, where the majority of providers are mid-level providers such as clinical officers and enrolled nurses. Mid-level providers are health professionals who seem to have no formal career structures, and little opportunity for promotion.Citation18 We have shown that their job satisfaction is influenced by their work assignments, how they perceive their promotion opportunities relative to others doing the same work and how they are treated by their managers. Unless these largely hidden behavioural aspects of the work environment are addressed, these cadres, who are currently the mainstay of maternal health provision in Malawi, are likely to leave the health sector for more attractive employment opportunities elsewhere. Changing this is at least partly within the power of local health facility managers to address.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the Advisory Board of Irish Aid for funding this study. We are also extremely grateful to all of the health care providers who participated in the study.

References

- Government of Malawi. Human Resources Capacity Development within the Health Sector: Needs Assessment Study. 2007; Malawi Health SWAp Donor Group.

- Government of Malawi. Health Management Information Bulletin. 2007; Department of Planning, Ministry of Health: Lilongwe.

- PM Fenton, CJ Whitty, F Reynolds. Caesarian section in Malawi: prospecive study of early meternal and perinatal mortality. BMJ. 327: 2003; 587–591.

- G Chilopora, C Pereira, F Kamwendo. Postoperative outcomes of caesarian sections and other emergency obstetric surgery by clinical officers and medical offices in Malawi. Human Resources for Health. 5: 2007; 17.

- G Dassault, C Franceschini. Not enough here, too many there: understanding geographic imbalances in the distribution of health personnel. 2003; World Bank Institute: Washington DC.

- U Sara. Health sector human resources crisis in Africa: an issues paper. 2003; Support for analysis and research in Africa. Bureau for Africa. Office for Sustainable Development: Washington DC.

- Ghana Ministry of Health. Internal report on Human Resources; 2002.

- K Wyss, DD Moto, N Yemadji. Human resources availability and requirements in Chad. 2002; Swiss Center for International Health, Swiss Tropical Institute: Basel.

- EJ Mills, WA Schabas, J Volmink. Should active recruitment of health workers from sub-Saharan Africa be viewed as a crime?. Lancet. 371(23 Feb): 2008; 685–688.

- Government of Malawi. A Six-Year Emergency Pre-Service Training Plan. Department of Planning, Ministry of Health; 2001–2002.

- Government of Malawi. Human Resources in the Health Sector: Towards a Solution. Ministry of Health; 2004.

- M Kawonga, S Fonn. Achieving effective cervical screening coverage in South Africa through human resources and health systems development. Reproductive Health Matters. 16(32): 2008; 32–40.

- D Palmer. Tackling Malawi's human resources crisis. Reproductive Health Matters. 14(27): 2006; 27–39.

- L Penn-Kekana, D Blaauw, KS Tint. Nursing staff dynamics and implications for maternal health provision in public health facilities in the context of HIV/AIDS. 2005; Centre for Health Policy, University of Witwatersrand: Johannesburg.

- I Mathauer, I Imhoff. Health worker motivation in Africa: the role of non-financial incentives and human resource management tools. Human Resources for Health. 4: 2006

- D Dovlo. Using mid-level cadres as substitutes for internationally mobile health professionals in Africa: a desk review. Human Resources for Health. 2: 2004

- RN Manongi, TC Marchant, CI Bygbjerb. Improving motivation among primary health care workers in Tanzania: a health worker perspective. Human Resources for Health. 4: 2006

- S Bradley, E McAuliffe. Mid-level providers in emergency obstetric and newborn healthcare: factors affecting their performance and retention within the Malawian health system. Human Resources for Health. 7(14): 2009

- JP Huddart, OF Picazo. The health sector human resource crisis in Africa: an issues paper. 2003; US Agency for International Development, Bureau for Africa, Office of Sustainable Development: Washington DC.

- N Gerein, A Green, S Pearson. The implications of shortages of health professionals for maternal health in sub-Saharan Africa. Reproductive Health Matters. 14(27): 2006; 40–50.

- E McAuliffe, C Bowie, O Manafa. Measuring and managing the work environment of the mid-level provider: the neglected human resource. Human Resources for Health. 7(13): 2009

- J Greenberg. The social side of fairness: interpersonal and informational classes of organizational justice. R Cropanzano. Justice in the Workplace: Approaching Fairness in Human Resource Management. 1993; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Mahwah NJ, 79–103.

- A McDowall, C Fletcher. Employee development: an organizational justice perspective. Personnel Review. 33(1): 2004

- R Cropanzano, R Folger. Referent cognitions and task decision autonomy: beyond equity theory. Journal of Applied Psychology. 74: 1989; 293–299.

- R Folger, MA Kovonsky. Effects of procedural and distributive justice on reactions to pay raise decisions. Academy of Management Journal. 2: 1989; 115–130.

- Y Cohen-Charash, PE Spector. The role of justice in organisations: a meta-analysis. Organizational Behaviour and Human Decision Processes. 86: 2001; 278–321.

- JA Colquitt, DE Conlin, MJ Wesson. Justice at the millennium: a meta-analytic review of 25 years of organizational justice research. Journal of Applied Psychology. 86: 2001; 425–445.

- BP Niehoff, RH Moorman. Justice as a mediator of the relationship between methods of monitoring and organisational citizenship behaviour. Academy of Management Journal. 36: 1993; 527–556.

- RH Moorman. Relationship between organizational justice and organizational citizenship behaviours: do fairness perceptions influence employee citizenship?. Journal of Applied Psychology. 76: 1991; 845–855.

- Podsakoff PM, McKenzie JB. A second generation measure of organizational citizenship behaviour. Indiana University, 1989. (Unpublished)

- J Graham. Organizational citizenship behaviour: construct redefinition, operationalisation and validation. 1989; Loyola University: Chicago. (Unpublished).

- DW Organ. The motivational basis of organizational citizenship behaviour. BM Shaw, LL Cumming. Research in Organizational Behaviour. 1990; JAI Press: Greenwich CT.

- U Krogstad, D Hofoss, M Veenstra. Predictors of job satisfaction among doctors, nurses and auxiliaries in Norwegian hospitals: relevance for micro unit culture. Human Resources for Health. 4: 2006

- M Dieleman, PV Ciong, LV Anh. Identifying factors for job motivation of rural health workers in North Vietnam. Human Resources for Health. 1: 2003

- DB McFarlin, PD Sweeney. Distributive and procedural justice as predictors of satisfaction with personal and organizational outcomes. Academy of Management Journal. 35: 2004; 626–637.

- G Latham, C Pinder. Work motivation theory and research at the dawn of the twenty-first century. Annual Review of Psychology. 56: 2005

- L Penn-Kekana, B McPake, J Parkhurst. Improving maternal health: getting what works to happen. Reproductive Health Matters. 15(30): 2007; 28–37.