Abstract

While Chile sees itself as a country that has fully restored human rights since its return to democratic rule in 1990, the rights of teenagers to comprehensive sexuality education are still not being met. This paper reviews the recent history of sexuality education in Chile and related legislation, policies and programmes. It also reports a 2008 review of the bylaws of 189 randomly selected Chilean schools, which found that although such bylaws are mandatory, the absence of bylaws to prevent discrimination on grounds of pregnancy, HIV and sexuality was common. In relation to how sexual behaviour and discipline were addressed, bylaws that were non-compliant with the law were very common. Opposition to sexuality education in schools in Chile is predicated on the denial of teenage sexuality, and many schools punish sexual behaviour where transgression is perceived to have taken place. While the wider Chilean society has been moving towards greater recognition of individual autonomy and sexual diversity, this cultural shift has yet to be reflected in the government’s political agenda, in spite of good intentions. Given this state of affairs, the Chilean polity needs to recognise its youth as having human rights, or will continue to fail in its commitment to them.

Résumé

Alors que le Chili se voit comme un pays qui a pleinement rétabli les droits de l’homme depuis son retour à la démocratie en 1990, les droits des adolescents à une éducation sexuelle complète ne sont toujours pas satisfaits. Cet article examine l’histoire de l’éducation sexuelle au Chili et la législation, les politiques et les programmes liés. Il fait également état d’une analyse du règlement d’un échantillon aléatoire de 189 écoles chiliennes, qui a révélé que même si ces textes sont obligatoires, l’absence de règlement pour prévenir la discrimination en raison d’une grossesse, du VIH et de la sexualité était fréquente. Les réglements qui ne respectaient pas la loi sur le traitement du comportement sexuel et la discipline étaient nombreux. L’opposition à l’éducation sexuelle dans les écoles chiliennes se fonde sur le refus de la sexualité adolescente, et beaucoup d’écoles punissent ce qu’elles jugent être une transgression sexuelle. Alors que la société chilienne plus large a évolué vers une reconnaissance accrue de l’autonomie individuelle et de la diversité sexuelle, cette orientation culturelle ne se retrouve pas encore dans le programme politique du Gouvernement, en dépit de bonnes intentions. Dans cette situation, la classe politique chilienne doit reconnaître que les adolescents ont des droits, sous peine de trahir ses engagements à l’égard de la jeunesse.

Resumen

Aunque Chile se ve a sí mismo como un país que ha restablecido plenamente los derechos humanos desde que se reinstauró la democracia en 1990, aún no se realizan los derechos de la adolescencia a la educación sexual completa. En este artículo se revisa la historia reciente de la educación sexual en Chile y la legislación, políticas y programas relacionados. También se informa sobre un estudio de 2008 de los reglamentos de 189 escuelas chilenas seleccionadas al azar, donde se encontró que aunque dichos reglamentos son obligatorios, la ausencia de reglamentos para evitar la discriminación por motivos de embarazo, VIH y sexualidad era común. En cuanto a la forma en que se trata el comportamiento sexual y la disciplina, los reglamentos que no cumplían con la ley eran muy comunes. La oposición a la educación sexual en las escuelas de Chile se basa en la negación de la sexualidad de los adolescentes, y muchas escuelas castigan el comportamiento sexual cuando se percibe que ha ocurrido transgresión. Aunque la sociedad chilena en general se ha movido hacia un mayor reconocimiento de la autonomía individual y la diversidad sexual, aún falta reflejar esta transición cultural en la agenda política del gobierno, pese a las buenas intenciones. En vista de esta situación, el sistema de gobierno chileno debe reconocer que su juventud tiene derechos humanos; de lo contrario, continuará fracasando en su compromiso a estos.

Chile is a country of stark contrasts. While progressive health care measures have reduced maternal morbidity and mortality rates to industrialised country levelsCitation1 and nearly 99% of births take place in a hospital setting,Citation2 the teenage birth rate stands at almost 15% of registered births nationally.Citation3

Public health data show that live birth rates in women under the age of 19 are class-sensitive, increasing as socio-economic status decreases.Citation4 The teenage birth rate in better-off areas of Santiago, the capital, is less than 4% of all births,Citation5 similar to the rates of the Netherlands, Norway and Sweden. The more disadvantaged districts have rates of 10–20%, as in Colombia and the Dominican Republic, while in the most disadvantaged areas, more than 20% of all births are to teenage mothers, similar to African countries such as Ghana.Citation6 This reflects a significant contradiction in Chilean society: abundance alongside neglect.Citation7Citation8 Official Chilean concern about teenage pregnancy dates back to the 1960s, when the government created a Committee on Family Life and Sex Education (Comité de Vida Familiar y Educación Sexual) under the Ministry of Education. In 1972 the government launched a comprehensive sexuality education programme, only to see it terminated after the 11 September 1973 military coup.Citation9

The return to democracy in 1990 created great expectations of a new cultural and political climate. While Chile sees itself as a country that has fully restored human rights since 1990, sexual and reproductive health policies, programmes and public discourse lack a consistent human rights and gender focus.

Methodology

This article examines some of the factors that led to the plight facing sexuality education in Chile today. It reviews the recent history of sexuality education in Chile and related legislation, policies and programmes, and looks especially at their impact on adolescents’ rights. We analyse official documents including laws, motions from the Chilean Congress and documents from the Ministry of Education and National Statistics Institute, documentation from the World Health Organization (WHO), the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), human rights reports and academic articles, cases in 2004 and 2006 in the Court of Appeals of Santiago, a 2008 case in the Constitutional Court of Chile and media reports from two leading newspapers, El Mercurio and La Nación related to sexuality education and adolescent sexuality.

In this context, we report on a study of school bylaws in the Santiago metropolitan region, which we conducted in 2008,Citation10 whose aim was to determine whether the bylaws were in keeping with Chilean and international human rights law, and their main strengths and limitations. The methodology consisted of analysing the school bylaws of a random sample of 250 schools (22% of the total in selected educational districts). The final sample included 189 schools’ regulations; the other 61 did not make their bylaws available. Finally, we conducted semi-structured interviews with school heads, teachers, parents and student representatives from seven schools.

A society with double standards

Shallat, Blofield and Shepard characterise Chile as a society with glaring double standards.Citation11 Citation12 Citation13 Sex and sexuality are everywhere and are used to sell beer, cars and deodorant. There is an ongoing tension between the government, which has attempted to take steps to support adolescent well-being through NGO condom drives and sexuality education initiatives, and the political and social elites, who try to prevent these efforts from bearing fruit. These elites consist of right-wing political figures, including parliamentarians, municipal staff and Catholic religious leaders. One of their first victories was in 1997, when the Supreme Court refused to order two TV stations, including one run by the Catholic University, to carry Health Ministry spots on HIV prevention and condom use.Citation14 In 2003, right-wing municipal officials responded to prevention campaigns on STIs and unwanted pregnancy by fining NGO health workers who were distributing free condoms in Chilean summer resorts. The local Bishop, Jorge Medina, today a Vatican official, said of these health workers that Satan wears many disguises.Citation15

In 2006, two mayors challenged family planning technical norms in court on the grounds that parents had to be informed about sexual activity in their children, and that allowing the prescription of emergency contraception without parental involvement interfered with the constitutional rights of parents to educate their children.Citation16 These efforts resulted in the Constitutional Court banning emergency contraception from the public health care system,Citation17 even though the private health care system and pharmacies are still allowed to provide it. Every attempt to integrate sexuality education in the school curriculum is fought tooth and nail by these forces. Since 1990, however, governments in Chile have lacked the political will to tackle issues thought likely to cause an outcry among the opposition and the clergy and bring about a rift in the ruling coalition. This is not to say that no progress has been made, but every step forward is hampered by opposition.

Treatment of young people’s sexuality is directly connected with the ethics, values, mores, and attitudes towards sex prevailing in the adult world. Teenagers not only face restrictions on information at home, they also depend on health care providers for sexual and reproductive health services. Public discourse and policy implementation show the wide gap between unrealistic adult perceptions that teenagers are celibate or asexual beings and their actual needs and rights in this respect. Even when teenage sexuality is acknowledged, policymakers and society tend to treat it as problematic,Citation10Citation18 as if adolescents need to be protected from themselves. For example, in 2004 the Chilean law on statutory rape was modified with the aim of providing greater protection for young adolescents, but was then followed by a policy establishing a legal obligation on health care professionals and teachers to report any adolescent under the age of 14 who was sexually active or sought contraceptives. This led to the refusal of services, reports to the authorities and non-compliance with reporting, which risks sanctions.Citation19Citation20

A history of sexuality education programmes

The current structure and legal framework of the Chilean education system (public schools run by local governments and publicly-subsidised privately-run schools) are a legacy of the Pinochet dictatorship, governed by an Education Act passed furtively in March 1990, in the dying hours of the Pinochet regime. Although public policy is under the purview of the Executive and subject to internal political debate, law reform requires Congressional approval.Citation21 The quasi-constitutional nature of the Act requires a 4/7ths majority in both chambers of Congress to amend; hence, all changes have been subject to excruciatingly slow bargaining, mostly with former Pinochet supporters and conservative members of Congress.

As Chile ratified most international human rights instruments, including the Convention on the Rights of the Child, after 1990, NGOs and academic institutions demanded policies to address high rates of teenage pregnancy and HIV infection. In 1991 a Commission was convened to propose major sexuality education policy reform that was eventually adopted two years later. The new policy provided a framework that took full account of the interests of school principals, administrators, teachers, parents and religious officialsCitation22 but left content up to the school community – a procedural compromise designed to circumvent sharp political differences and widely conflicting views. The premise was that since sexuality education was important for children and young people, and families had a primary role in imparting it, schools would design their own programmes, with parental involvement.Citation22 The Commission’s inability to reach consensus also led to parents being given the right to keep children from participating in sexuality education. The Commission’s official statement argued that freedom of thought and school autonomy were pivotal to public policy on thorny issues such as sexuality:

“Considering that ... incorporating a common discourse into the school curriculum was impossible, a mechanism is required to decentralise decision-making on issues where many diverse norms, values and beliefs exist.” Citation22

JOCAS: conversations on relationships and sexuality

Experts in the field and sexuality education advocates regarded this result as a partial victory: at least some degree of sexuality education would be implemented, providing a foundation on which further action could then be taken. However, it took two years before a pilot project, begun with support from UNFPA, the Education Ministry and other government agencies, began work on JOCAS (Jornadas de Conversación sobre Afectividad y Sexualidad, Conversations on Relationships and Sexuality), a programme consisting of three-day workshops for students, parents and teachers.Citation23 This is a massive event, where all participants are convened to work in small group sessions lasting 90 minutes each for three days. By the end, the school and the rest of the community should have identified the needs and strengths of the community so as to integrate sexuality and relationships into the school curriculum.Citation24 After a test run in five schools in 1995,Citation23 JOCAS were introduced more widely in 1996. A loud outcry from the Roman Catholic hierarchy ensued, which pronounced the initiative “devoid of moral values” and claimed sexuality was a private issue best left to families.Citation23 The staunchly Catholic Private Schools Federation and the government opposition also became vocal critics.Citation25 The Ministry held fast, hoping that, in time, JOCAS would catch on and school communities would start developing curricula.Citation24 However, by 1999 less than 37% of all publicly-funded schools had done so.Citation23

By the end of 2000, when JOCAS was to begin again as an joint Ministry initiative, opposition by the Church and the Federation of Catholic Schools resurfaced. They argued that JOCAS heavily emphasised health criteria, not values or mores.Citation25 The programme was suspended after an outcry against a talk in a school on how to use a condom, demonstrated using a banana.Citation26 The Minister of Education stated that education on birth control methods was to be limited to community health clinics and was not to take place in schools.Citation25 By the end of November of 2001, JOCAS were dropped by the government as an official initiative, due to the pressure from right-wing politicians and Catholic church leaders. The Catholic Schools spokesperson insisted that the sexuality education programme only legitimised irresponsible and immature sex for minors, as taught under the purview of the Ministries of Education and Health and the Women's Bureau.Citation25 The media reported that the programme, intended to begin in eight municipalities, was stalled due to Church opposition. The pilot project was later implemented, and in spite of civil society demands for information, it took more than five years for the outcomes to be partially disclosed.Citation26 These revealed that 85% of students felt they had learnt with JOCAS and valued the open space to discuss sexuality, while 75% of teachers noted that JOCAS strengthened their relationship with students.Citation26

JOCAS are still remembered as a crucial experience in school integration of sexuality education. They were popular – so much so that some schools continue to apply the model to this day. They had a nationwide outreach and were unique, in that the dynamics rested solely on the participants. They were perceived to be democratic and appealing to the target audiences. Their weakness was that they were conceived as a series of continuing “events”, which needed continuity in order to meet the ongoing needs of young people through the education system.Citation9 School counsellors, heads and administrators surveyed by the Ministry of Education in 2004 said that while JOCAS were productive, lack of continuity caused momentum to be lost.Citation27

Today, most private schools have some type of sexuality education programme but only a few publicly-funded schools. In addition, less than 10% of teachers have acquired the skills to deal with sexuality in the classroom.Citation8 There have been a few isolated initiatives, yet without the necessary continuity to become established. The torch has been passed to a variety of academic and NGO programmes, which range from provision of contraceptive and STI services to teenagers to promotion of abstinence.Citation9 Citation28 Citation29 Citation30

In these circumstances, a popular phone-in radio show heard nationwide starting in 1996 became a leading source of sexuality information for teens and young people.Citation31 The show’s genial host succeeded where public policy had not, getting Chilean youth to talk freely and unreservedly about sex.

The underlying cultural shift catalysed by a recovered democracy was also evident elsewhere. For example, the Sunday edition of a tabloid notorious for cover photos of minimally attired women started a section on Health and RelationshipsCitation8 that takes queries from its mostly working-class readers, with responses provided by prominent sexual and reproductive health specialists. Interestingly, questions posed by readers in the 11-19 age group fall largely within five areas: intercourse (including anal and oral sex), anatomy and genitalia, teenage pregnancy, homosexuality and STIs, and masturbation. The 2004 Ministry of Education survey revealed that over 60% of students relied on television for most of their information on sex.Citation27 Concerned at this turn of events, Chile Unido, a conservative agency working on family issues and anti-abortion, successfully lobbied the tabloid owners to let them provide a conservative viewpoint on these matters. The urgent need for comprehensive, accurate information for teenagers persists.Citation8 Meanwhile, the Education Ministry had to shelve a publication for parents designed as part of a sexuality education drive after it contents on masturbation were deemed offensive.Citation1

Another attempt at public policy on sexuality education

To show that there has been progress, Shepard used the analogy of the half-full vs. half-empty glass to assess the JOCAS and sexuality education programme.Citation13 While we agree, expectations for the Lagos and Bachelet administrations in this respect have been particularly high. However, progress on certain issues, including sexuality, can lag behind even under often progressive administrations. In 2004 the Education Ministry under Lagos convened a Commission to review matters since 1993 when the Sex Education Policy was passed. Members included teachers, parents, principals, students and experts in sexuality education and other fields (including author Casas). The Commission encountered the pent-up frustration of community groups at government failure in this area during the previous decade. On the other hand, conservatives warned the Commission against introducing mandatory sexuality education in schools, arguing that the Constitution protected freedom of education and prevented government from changing the law or policy.

The Commission found that while the 1993 policy claimed to be grounded in human rights, there was no mention of the rights of the child. The 1993 policy described at length the rights and duties of parents but neglected to emphasise the importance of adolescents’ ability to protect their health and physical integrity. Since the Convention on the Rights of the Child had been ratified only a few years earlier, it could be argued that the 1993 policy drafters lacked a thorough understanding of its implications. The new Commission noted that it was of pivotal importance for changes in policy to be in line with the Convention and all human rights instruments with a bearing on sexuality education.Citation27

The procedural consensus of 1993 was based on the premise of parental and family involvement, but little of the sort actually occurred. A 2005 Education Ministry survey found that less than one third of private schools had invited parents to sexuality workshops. The figure for public schools run by local government was less than 12%.Citation27 Unless pressured, most schools were clearly not open to addressing these issues. Surveys and testimony heard by the Commission exposed the fact that most teachers lacked the skills and educational materials required to provide sexuality education, and that much work and energy were needed to change this. In 2005, the Commission, in closing, called for respect for the diversity of views on sexuality and the need for the government to step in where families were not providing sufficient information or support. They proposed a five-year plan to invite schools to develop new sexuality education curricula, starting in 2005.Citation32 Yet, the Minister of Education of the incoming Bachelet government lowered the priority and pulled the funding. One activist referred to this turn of events as “the end of sexuality education in Chilean schools”.Citation33

Absence of legally mandated bylaws on sexuality issues in schools

School bylaws, required by law, are internal codes setting down a school’s guiding principles and rules on disciplinary matters, dress and punctuality, and generally regulate student behaviour. Although they should be drafted in collaboration with the entire school community, in practice they are set by administrators with little input from parents or students.

In 2000, legislation was passed banning discrimination against pregnant and parenting students, allowing them flexible school attendanceCitation34 and setting penalties for offending schools. It also prohibited expelling students during the school year for unpaid tuition fees and required publicly-funded schools to recruit at least 15% of their students from designated vulnerable groups.Citation35 These changes were intended to comply with the Convention on the Rights of the Child.

The Education Ministry had in fact been fighting against sex and gender discrimination, including expulsion on grounds of pregnancy, since 1991, when it first issued guidelines regarding pregnant students.Footnote* In a 2004 Ministry of Education survey, 90% of parents, 82% of students and 75% of teachers thought that pregnant students should not be discriminated against.Citation27 In 2004, an administrative regulation mandated maternity leave before and after childbirth aimed at helping students stay in school.Citation36 Additionally, a law in 2000 and 2001 banned discrimination against pregnant students and HIV-positive students,Citation34Citation37 and the Ministry issued guidelines on how to support retention of HIV-affected children and teenagers.

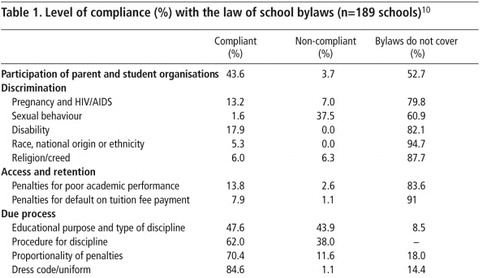

In 2007, UNICEF and the Education Ministry commissioned a study of school bylaws, discrimination and due process of lawCitation10 to determine whether school bylaws were compliant with Chilean law and human rights, how they were drafted and applied and whether any penalties had an educational purpose. The school bylaws we examined fell into three categories: compliant (legal requirements were met, even if minimally or formally), non-compliant (inconsistent with the law), or not covered at all. While most of the bylaws appeared to be compliant, the extent of non-compliant rules and omitted topics was significant and a matter for concern (Table 1

). Many bylaws equivocated on procedures for imposing penalties, while regulating other aspects to the extreme, e.g. dress code on piercing, hair length, clothing style and colour, and accessories.Table 1 shows that the absence of bylaws on pregnancy, HIV, and sexuality and discrimination is far greater than compliant or non-compliant bylaws. Non-compliance was also very high in relation to how sexual behaviour and discipline were addressed.

Some 80% of school bylaws made no mention of pregnancy or HIV and over 60% ignored sexual behaviour. The only aspect explicitly mentioned in compliant bylaws was pregnancy. Awareness of pregnancy-related discrimination issues appeared to be high, and all respondents interviewed said that their school bylaws had been amended as per the new law. One principal acknowledged that although the Education Ministry order directing schools not to expel pregnant students dated back to 1991, in practice his school’s bylaws were amended only after 2000. In all cases where the bylaws in question were found to be compliant, their regulations were based on maternity leave regulations in the 2004 labour law.Citation36 These included: from the seventh month of pregnancy, students are no longer required to attend class. They should come in once a week to pick up and return homework and write tests, and go back to school three months after delivery. One school extended the maternity leave period, arguing that it did not have the infrastructure to accommodate pregnant students and did not wish to be held liable if something went wrong.

Sexuality was found to be regulated in ways inconsistent with privacy rights (37.5%), banning everything from expression of affection, where couples meet and how they must behave, even outside the school grounds and in their free time. These norms, school officials said, aimed to ensure that students did not consider schools “a public park or a living room”. In mixed-sex schools, dating was generally allowed but “expressions of great affection” were not. At times, school codes used language that was obsolete or obscure by most young people’s standards. For example, some schools banned behaviour “contrary to morals and decency”, interpreted by some officials as kissing and fondling and by others as having sex on the premises. One school even banned dating or fondling within a set radius around it.

In the 2004 Ministry of Education survey, 79% of students and 81% of teachers thought gays and lesbians should not be forced to keep their sexual orientation secret.Citation27 While most schools had working or unwritten rules on sexual orientation, ranging from tolerance as long as there were no public “expressions of homosexuality” to the assertion that “it did not happen”, interviews showed that attitudes toward homosexuality were wide-ranging. While all student respondents were aware of fellow gay and lesbian students, principals and teachers did not always share this awareness. A frequent student answer was that gays and lesbians were not singled out for harassment provided they were discreet. One principal argued that he should not be asked to accept what the wider society had not; others were not aware of gay or lesbian students in their schools. In our study, students and parents recognised that students had been expelled on grounds of sexual orientation and the school culture obliged them to remain “in the closet”.

These findings illustrate the difficulties Chilean schools face when it comes to admitting that children and teenagers are sexual beings with rights. Chilean society has been moving towards greater tolerance and awareness of diversity, including with regard to sexuality. Our interviews, particularly with students, are testimony to their awareness of these matters.Citation10 Much of the adult world, however, has yet to see and appreciate this diversity to the same extent.

Punishment of sexuality

These findings convey a narrative of sexuality being denied or punished in Chilean educational settings. The absence of bylaws and non-compliant bylaws show a failure to recognise teenagers as holders of rights, and this translates into public controversy whenever their sexuality comes to the fore. At the judicial level, sexuality is viewed through a moral lens, and is restricted solely to adults. This was apparent in a case brought against a Chilean television station that showed teenagers engaging in a game of “cultural striptease” involving suggestive dancing and the removal of pieces of clothing.Citation38 The Court ruled the segment was objectionable, because it “invites under-age individuals to naturally follow analogous behaviours that, clearly, are more appropriate for the adult world. The programme projects the idea that sexuality is free of affection, and invites them precociously to discover a reality that is still unfamiliar to them, which does not contribute to the spiritual and intellectual development of children and youth. The latter is an essential mission of the media, especially television, due to its impact.”Citation38

The Chilean media have reported for years on students being expelled from schools for sexuality-related behaviour. Teenagers are discriminated against for getting pregnant or wearing attire deemed to be against “moral values”. Even when cases have gone to court, students have not always been protected from discriminatory rulings. Schools have argued that parents and students are bound by their internal rules and should not complain about procedures or penalties imposed.Citation39

Schools still tend to react with dismay whenever student sexuality surfaces. In the past few years, several gay and lesbian students have gone public through court cases, marches and the media to demand that the Ministry of Education take action against discrimination in their school. In 2005 a Brigade of Gay and Lesbian High School students was formed seeking to stamp out discrimination in the education system. This collective was hosted by the Movement of Homosexual Integration and Liberation.Citation40 Such initiatives have had varying degrees of success. In 2004, for example, 300 students held a rally in protest at the dismissal of two gay students, leading to their successful reinstatement. However, many cases do not reach public light and much remains to be done.Citation41

The ideals of abstinence and celibacy proclaimed by most Catholic-run schools are a particularly notorious part of the culture of control and repression.Citation42Citation43 In late 2007, the media reported that a teenage couple, concerned about having had unprotected sex, were suspended after asking a school counsellor about emergency contraception. The suspension was lifted only after the Education Ministry intervened.Citation44

Gender discrimination was also at play in the case of a girl unwittingly videotaped while performing oral sex on a classmate in a public park. The video clip was uploaded to a popular website. Arguing that she had compromised the reputation of the school and its female students, the school asked the girl to find alternative placement but took no action against her sexual partner or the male classmates who captured the scene on their cell phones.Citation45

The Ministry of Education has also had to step in in cases involving gay or lesbian students harassed or expelled from school on sexual orientation grounds.Citation43 Such discrimination is frequently reported by activists. It is not common for students to take these cases to Court, as judges are hard to predict. Adolescents end up “voluntarily withdrawing from school” as it was euphemistically described in our study.Citation10

What does the future hold

2009 is an election year and for the first time since 1990, it is far from clear whether the centre–left coalition will be able to remain in power. In spite of good intentions, the government’s political agenda is continually being eroded by political forces that refuse to consider young people as sexual beings with rights.

The Rights Protection Unit of the Ministry of Education makes important efforts to foster rights awareness and secure students’ rights whenever cases of discrimination have taken place in schools, especially with regard to suspensions.Citation43 However, most of these initiatives have little impact on public policy and law. Today, the issue is the lack of willingness to open a dialogue on rights, gender and sexuality among young people. The absence of an effective national sexuality education programme is borne most by the poorest in Chilean society because services in the private sector are not affected, only the public sector.

The requirement of a 4/7ths majority in both houses of Congress hampers law reform, and conservative rhetoric has not let up. We believe the threat of litigation will deter any government attempt to introduce mandatory sexuality education in schools through public policy or legal reform. These issues are present in the current debate on the Birth Control and Emergency Contraception Bill, tabled in June 2009 by President Bachelet, to secure all methods of birth control, including emergency contraception, in the public health care system.Citation46

As the presidential election in December 2009 approaches, teenage sexuality has become a bargaining chip with the opposition, who have a candidate running high in the polls. The opposition in the Chamber of Deputies tabled an amendment to the new bill, obliging health care providers to inform parents or another adult when they prescribe emergency contraception to any girl aged 14-16, whenever they deem the teenager’s health or life to be in urgent need of protection.Citation47 This was backed by the Executive, in hopes that it would reduce opposition to the bill. The amendment is a regressive measure, however, compared with the 2008 Constitutional Court decision on emergency contraception, that upheld teenagers’ right to confidential services.

When the Senate Health Committee approved the amended bill, two supporting Senators tabled another amendment, to establish mandatory sexuality education programmes in schools.Citation48 As the possibility of remaining in power is less predictable, some politicians are willing to put issues on the agenda that have divided the governing coalition. The pro-Pinochet UDI party has already announced it will challenge the bill in the Constitutional Court if it is passed by Congress.

Several UN treaty bodies have recommended that Chile adopt laws, policies, and programmes upholding sexual and reproductive rights.Citation49Citation50 But the status quo undermines, and ultimately violates, adolescents’ human rights. Unless the Chilean polity begins to consider its youth as holders of rights, Chile will continue to fail in its commitment to them.

Notes

* Circular 247 on pregnant students and breastfeeding promoted the right of pregnant students to continue their education, calling on schools to refrain from dismissing students because of pregnancy and establishing flexible norms regarding school attendance to enable them to take examinations. In an emblematic case, litigated first in the Court of Appeals of La Serena (Carabantes v. Araya, Case 21.633, 25 December 1997), the Supreme Court upheld a school’s decision to expel a pregnant student. However, her family brought a complaint before the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, which brokered a friendly settlement. Report No. 33/02, Friendly Settlement, Petition 12046, Mónica Carabantes Galleguillos v. Chile, March 12, 2002. At: <www1.umn.edu/humanrts//cases/33-02.html>. Accessed 25 February 2009.

References

- B Shepard, L Casas. Abortion policies and practices in Chile: ambiguities and dilemmas. Reproductive Health Matters. 15(30): 2007; 202–210.

- V Schiappacasse, P Vidal, L Casas. Chile: situación de la salud y los derechos sexuales y reproductivos. 2003; Corporación de Salud y Políticas Sociales, Institute of Reproductive Medicine Chile and Department on Status of Women: Santiago.

- National Statistics Institute. Fecundidad en Chile. Situación reciente. Santiago, 2006. p.10. At: <www.ine.cl/canales/chile_estadistico/demografia_y_vitales/demografia/pdf/fecundidad.pdf>. Accessed 15 February 2009.

- Instituto Nacional de Juventud, Observatorio de Juventud. 5ta Encuesta Nacional de Juventud. Santiago, 2007. p.165. At: <www.injuv.gob.cl/modules.php?name=Content&pa=showpage&pid=4>. Accessed 15 August 2009.

- WHO Europe. Atlas of Health in Europe. 2nd ed. Copenhagen, 2008. p.16. At: <www.euro.who.int/Document/E91713.pdf>. Accessed 15 August 2009.

- WHO UNFPA. Pregnant Adolescents, Delivering on Global Promises of Hope. 2006; WHO: Geneva, 8. At: <http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2006/9241593784_eng.pdf. >. Accessed 15 August 2009.

- Reproductive Medicine Institute of Chile. Adolescentes. At: <www.icmer.org. >. Accessed 15 August 2009.

- C Suárez, D Navarrete, P Riffo. Temas de la sexualidad que preguntan adolescentes en la prensa. Revista SOGIA. 11(3): 2004; 85. At: <www.cemera.cl/sogia/pdf/2004/XI3temas.pdf. >. Accessed 30 January 2009.

- O Collao, CG Honores. Hacia una pedagogía de la sexualidad. 2000; Viña del Mar: CIDPA, 15. At: <www.cidpa.cl/txt/publicaciones/Haciauna.pdf. >. Accessed 3 February 2009.

- L Casas, C Ahumada, L Ramos. La convivencia escolar: componente indispensable del derecho a la educación. Estudio de los Reglamentos Escolares. Revista Justicia y Derechos del Niño. 10: 2008; 317–340. At: <www.unicef.cl/unicef/public/archivos_documento/263/Justicia_y_Derecho_10_finalweb2008_arreglado.pdf. >. Accessed 5 February 2009.

- L Shallat. Rites and rights: Catholicism and contraception in Chile. Private Decisions, Public Debate: Women, Reproduction and Population. 1994; Panos: London, 152.

- M Blofield. The Politics of “Moral Sins”: A Study of Abortion and Divorce in Catholic Chile since 1990. 2001; FLACSO: Santiago.

- B Shepard. Conversation and controversies: a sexuality education programme in Chile. Running the Obstacle Course to Sexual and Reproductive Health: Lessons from Latin America. 2006; Praeger: Westport CN.

- L Cabal, J Lemaitre, M Roa. Cuerpo y Derecho: Legislación y Jurisprudencia en América Latina. 2001; Center for Reproductive Law and Policy, School of Law, University of Los Andes, Temis: Bogotá, 136.

- School of Law, Diego Portales University. Informe anual sobre derechos humanos en Chile 2004. Hechos de 2003. 2004; Diego Portales University: Santiago, 229–230. At: <www.udp.cl/derecho/derechoshumanos/informesddhh/informe_04/07.pdf. >. Accessed 4 February 2009.

- Corte de Apelaciones de Santiago. “Pablo Zalaquett y otro con Ministra de Salud”, rol 4693-2006. 10 November 2006.

- Constitutional Tribunal, Case 740-07, 22 April 2008. At: <www.tribunalconstitucional.cl>. Accessed 2 February 2009.

- S Moore, D Rosenthal. Adolescent sexual behaviour. D Roker, J Coleman. Teenage Sexuality. Health, Risk and Education. 1998; Harwood Academic Publishers: Amsterdam, 35.

- L Casas. Confidencialidad de la información médica, derechos a la salud y consentimiento sexual de los adolescentes. Revista SOGIA. 12(3): 2005; 94–111. At: <www.cemera.cl/sogia/pdf/2005/XII3confidencialidad.pdf. >. Accessed 17 August 2009.

- C Ahumada. Statutory rape law in Chile: for or against adolescents? Journal of Politics and Law 2009. At: <http://ccsenet.org/journal/index.php/jpl/issue/view/89. >. Accessed 10 August 2009.

- Constitution of Chile, Article 60.

- Ministry of Education, Política de Educación en Sexualidad. Para el mejoramiento de la calidad de la Educación. 5th ed. Santiago, 2003.

- E Guerrero, P Provoste, A Valdés. La desigualdad olvidada: género y educación en Chile. Equidad de género y reformas educativas. 2006; Hexagrama Consultoras, FLACSO-Buenos Aires, Instituto de Estudios Sociales Contemporáneos Universidad Central de Bogotá: Santiago, 123.

- Ministry of Education. Jornadas de Afectividad y Sexualidad. Santiago, 1999. At: <www.mineduc.cl/biblio/documento/jocas.pdf>. Accessed 2 February 2009.

- Reparos católicos a Plan Escolar sobre Sexualidad. El Mercurio. 23 August 2001. At: <http://diario.elmercurio.cl/detalle/index.asp?id=c65c9c04-bc3f-47d4-84b1-a079f8699e5e>. Accessed 17 August 2009.

- Araya E. JOCAS, ¿El regreso? La Nación. 15 September 2006. At: <www.lanacion.cl/prontus_noticias/site/artic/20060914/pags/20060914215658.html>. Accessed 17 August 2009.

- Ministry of Education. Comisión de Evaluación y Recomendaciones sobre Educación Sexual. Santiago, 2005.

- P Cid. La experiencia comunitaria sobre trabajo en sexualidad con jóvenes. 2004; Epes: Santiago.

- V Toledo, X Luengo. Impacto del programa de Educación sexual adolescencia “Tiempo de Decisiones”. R Molina, J Sandoval, E González. Salud sexual y reproductiva en la adolescencia. 2003; Editorial Mediterráneo: Santiago.

- P León, M Minassian, R Borgoño. Embarazo adolescente. Revista Pediatría Electrónica. 5(1): 2008; 46–48. (Online) At: <www.revistapediatria.cl/vol5num1/pdf/5_EMBARAZO%20ADOLESCENTE.pdf. >. Accessed August 20 2009.

- J Barrientos. ¿Nueva normatividad del comportamiento sexual juvenil en Chile?. Última Década. 14(24): 2006; 81–97. At: <www.scielo.cl/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0718-22362006000100005&lng=es&nrm=iso. >. Accessed 3 February 2009.

- D Solís. Sexualidad en los colegios. At: <www.clam.org.br/publique/cgi/cgilua.exe/sys/start.htm?infoid=2252&tpl=printerview&sid=51. > Accessed 20 February 2009.

- L Arenas. El fin de la educación sexual en Chile. At: <www.observatoriogeneroyliderazgo.cl/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=644&Itemid=2. >. Accessed 4 February 2009.

- Law 19.688, 5 August 2000. At: <sdi.bcn.cl/boletin/publicadores/legislacion_tematica/archivos/19688.pdf>. Accessed 20 February 2009.

- Law 19.979 28, October 2004. At: <www.mineduc.cl/biblio/documento/200708021802560.Ley199792004.pdf>. Accessed 20 February 2009.

- Ministry of Education, Decree 79, March 2004. At: <www.bcn.cl/leyes/236569>. Accessed 20 February 2009.

- Law 19.779, 2001. At: <www.bcn.cl/leyes/pdf/actualizado/192511.pdf>. Accessed 20 February 2009.

- Court of Appeals of Santiago, Case No. 10592-03, 19 April 2004. At: <www.poderjudicial.cl/index2.php?pagina1=causas/por_rol_solo_tribunal.php?corte=7&codigotribunal=6051007>. Accessed 20 February 2009.

- L Casas, J Correa, K Wilhelm. Descripción y análisis jurídico acerca del derecho a la educación y discriminación, Cuadernos de Análisis Jurídico No.12. 2001; Diego Portales University: Santiago, 115–230.

- Movimiento de Integración y Liberación Homosexual. Lanzan Primera Brigada de Estudiantes Gays y Lesbianas de Estudiante Media. Santiago, 2005. At: <www.movilh.cl/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=255>. Accessed 23 August 2009.

- Informe Anual. Derechos Humanos Minorías Sexuales Chilenas (Hechos 2007). Movilh. Febrero 2008, Santiago, Chile. At: <www.movilh.cl/documentos/VI-INFORMEANUAL-ddhh-2007.pdf>. Accessed 23 August 2009.

- Human Rights Center. Informe Anual sobre Derechos Humanos en Chile 2008. 2008; Universidad Diego Portales: Santiago, 242. At: <www.udp.cl/derecho/derechoshumanos/informesddhh/informe_08/Derechos_ninas_ninos.pdf. >. Accessed 20 February 2009.

- School of Law. Informe Anual sobre Derechos Humanos en Chile 2007. Hechos 2006. 2007; Universidad Diego Portales: Santiago, 293–295. At: <www.udp.cl/derecho/derechoshumanos/informesddhh/informe_07/minorias_sexuales.pdf. >. Accessed 20 February 2009.

- Gutiérrez N. Alumnos de octavo básico: suspendidos por pedir la ‘píldora’. El Mercurio. 27 November 2007. At: <http://diario.elmercurio.cl/detalle/index.asp?id=bf0b0c98-2f94-4300-a299-fca6f33795f2>. Accessed 5 February 2009.

- Colegio La Salle saca lecciones de un hecho que lo conmocionó. El Mercurio. 7 October 2008. At: <http://diario.elmercurio.cl/detalle/index.asp?id=a8069b68-0a01-4048-a23c-6bf80fe9f727>. Accessed 20 August 2009.

- Cámara de Diputados, Boletín 6582-11, Proyecto de Ley sobre Información, Orientación y Prestaciones en materia de Regulación de la Fertilidad. 30 June 2009. At: <http://sil.senado.cl/cgi-bin/index_eleg.pl?6582-11>. Accessed 17 August 2009.

- Cámara de Diputados, Boletín 706-357. Formula Indicaciones al Proyecto de Ley sobre Información, Orientación y Prestaciones en materia de Regulación de la Fertilidad. (Boletín N° 6582-11).15 julio de 2009.

- A Meneses. Comisión de Salud Senado da luz verde a píldora del día después. La Nación. 11 August. 2009. At: <www.lanacion.cl/prontus_noticias_v2/site/artic/20090811/pags/20090811191447.html. >. Accessed 17 August 2009.

- Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. Concluding Observations: Chile. 26 November 2004.

- Committee on the Rights of the Child. Concluding Observations: Chile CRC/C/15/Add.173 (3 April 2002).