Abstract

Abstract

This study investigated the reasons for continued high rates of home births in rural Shanxi Province, northern China, despite a national programme designed to encourage hospital deliveries. We conducted semi-structured interviews with 30 home-birthing women in five rural counties and drew on hospital audit data, observations and interviews with local health workers from a larger study. Multiple barriers were identified, including economic and geographic factors and poor quality of maternity care. Women's main reasons for not having institutional births were financial difficulties (n=26); poor quality of antenatal care (n=13); transport problems (n=11); dissatisfaction with hospital care expressed as fear of being in hospital (n=10); convenience of being at home and continuity of care provided by traditional birth attendants (TBAs) (n=10); and belief that the birth would be normal (n=6). These barriers must all be overcome to improve access to and acceptability of hospital birth. To ensure that the national policy of improving the hospital birth rate is implemented effectively, the government needs to improve the quality of antenatal and delivery care, increase financial subsidies to reduce out-of-pocket payments, remove transport barriers, and where hospital birth is not available in remote areas, consider allowing skilled attendance at home on an outreach basis and integrate TBAs into the health system.

Résumé

Cette étude a enquêté sur les raisons expliquant pourquoi la province rurale du Shanxi, en Chine septentrionale, continue d'enregistrer un taux élevé d'accouchements à domicile, malgré un programme national d'encouragement des naissances à l'hôpital. Nous avons mené des entretiens semi-structurés avec 30 femmes ayant accouché à domicile dans cinq comtés ruraux et avons utilisé les données des audits hospitaliers, les observations et les entretiens avec des agents de santé locaux réalisés dans le cadre d'une étude plus large. Nous avons identifié de multiples obstacles, notamment des facteurs économiques et géographiques, ainsi que la médiocrité des soins maternels. Les principales raisons décourageant les femmes d'accoucher en institution étaient les difficultés financières (n=26) ; la mauvaise qualité des soins prénatals (n=13) ; les problèmes de transport (n=11) ; l'insatisfaction quant aux soins hospitaliers exprimée comme peur de l'hospitalisation (n=10) ; la commodité d'être à la maison et la continuité des soins assurés par les accoucheuses traditionnelles (n=10) ; et la conviction que la naissance serait normale (n=6). Il faut surmonter tous ces obstacles pour améliorer l'accès à l'accouchement en milieu hospitalier et son acceptabilité. Afin de garantir une application efficace de leur politique nationale, les autorités doivent relever la qualité des soins prénatals et obstétricaux, augmenter les subventions financières pour réduire les frais à la charge des patientes, résoudre les difficultés de transport et, quand l'accouchement hospitalier n'est pas disponible dans les zones reculées, envisager d'autoriser une assistance qualifiée à domicile avec du personnel mobile et intégrer les accoucheuses traditionnelles dans le système de santé.

Resumen

En este estudio se investigaron las razones por las cuales las tasas de partos domiciliarios continúan siendo altas en las zonas rurales de la Provincia de Shanxi, en China septentrional, a pesar de que existe un programa nacional creado para promover partos hospitalarios. Realizamos entrevistas semiestructuradas con 30 mujeres que tuvieron partos domiciliarios en cinco condados rurales, y obtuvimos datos de auditorías hospitalarias, observaciones y entrevistas con trabajadores de la salud de un estudio más amplio. Se identificaron múltiples barreras, como factores económicos y geográficos y la deficiente calidad de la atención materna. Las principales razones por las cuales las mujeres no tuvieron partos institucionales fueron dificultades financieras (n=26); calidad deficiente de la atención antenatal (n=13); problemas de transporte (n=11); insatisfacción con la atención hospitalaria expresada como miedo de estar en el hospital (n=10); conveniencia de estar en la casa y continuidad de la atención brindada por parteras tradicionales (n=10); y la creencia de que el parto sería normal (n=6). Se deben superar todas estas barreras para poder mejorar la accesibilidad y aceptación de los partos hospitalarios. Para asegurar una implementación eficaz de la política nacional de mejorar la tasa de partos hospitalarios, el gobierno debe mejorar la calidad de la atención antenatal y durante el parto, aumentar los subsidios financieros para reducir los pagos de las pacientes, eliminar las barreras de transporte y, en las zonas remotas donde el parto hospitalario no es posible, considerar permitir asistencia calificada en la casa, como extensión a la comunidad, e integrar a las parteras tradicionales en el sistema de salud.

One of the indicators for reducing maternal mortality and morbidity of Millennium Development Goal 5 is the rate of skilled birth attendance. Because of it, many developing countries, including China, have begun to focus on increasing the number of births with a skilled birth attendant. Although skilled attendants can attend deliveries at women's homes as well as in health facilities if the conditions are safe and as long as there is access to hospital care for obstetric emergencies, most countries are mainly trying to increase facility-based births.Citation1

In China, encouraging women to give birth at all levels (township, county, provincial) of public hospitals has been a major national strategy, begun in July 1995 to reduce deaths.Citation2 Studies published in 2007 and 2008 from different parts of China found that 30–80% of maternal deaths occurred with home births.Citation3–6 National maternal mortality surveillance data for 1996–2000 showed the maternal mortality ratio (MMR) for women who gave birth at home was three to four times higher than those who gave birth in hospital.Citation7 The Chinese government has employed incentives and disincentives to promote hospital births. For example, the New Rural Cooperative Medical Scheme (NRCMS), which began in 2003, partially reimburses hospital birth costs if the birth is authorized by the local Family Planning Bureau under the Chinese one-child policy.Citation8 In another national project, Decreasing the Maternal Mortality Ratio, Eliminating Newborn Tetanus (Decreasing Project), which began in 2000 in the 12 western rural provinces with the highest MMR, one incentive is to reimburse 10–40% of the costs for all the women who deliver in hospital. In 2010, the project has covered almost all the western rural poor provinces.Citation9

Around the year 2000, in nearly all provinces, TBAs' licences were abolished by the local provincial Health Bureaus and home birth was defined as “illegal”.Citation10 This was explained by concerns about the poor quality of care that TBAs provided as well as wanting women to go to hospital for a safe birth. TBAs' responsibilities were to change from attending births to providing antenatal and postnatal care and escorting women to hospital to deliver.Citation11 Those TBAs who continued to provide home birthing services without a licence could be fined up to 20,000 Yuan.Citation12 In many provinces, women who deliver at home with a TBA are no longer able to get a birth certificate for the baby.Citation13 These strategies seem to have made a significant change in Chinese maternity care. According to the official Chinese reports,Citation14 the hospital birth rate had improved nationally from 79.4% in 2003 to 91.7% in 2007, and the MMR had declined from 51.3 to 36.6 per 100,000 live births at the same time. Whether the lower MMR was due entirely to hospital births and declining TBA use has not been studied.

The large geographic and socio-economic variability in China influences uptake of hospital birth. Rates in 2006 varied from 25% in Tibet to over 97% in Jiling Province, even with the Decreasing Project.Citation15 Many women still give birth at home, especially in rural and/or poor areas in China, where most maternal deaths occur. For example, the Chinese National Maternal and Child Health Surveillance Office analysed 1,682 maternal deaths occurring in 2007 in all 1,000 counties covered by the Decreasing Project and found that 25.6% of births were at home.Citation16 It is important therefore to identify the barriers to hospital delivery that remain in these areas.

China's health system has changed from a publicly funded, primary health care-focused system to a market-oriented system since 1978, when Deng Xiaoping instituted an “open” policy.Citation17 Local government, rather than the central government, became responsible for funding health care. In most places, especially the poorer areas, however, local governments have not been able to cover fixed hospital costs, and hospitals have had to charge patients to make up the difference.Citation18 In 1985, central government decentralized hospital management, giving hospital directors more autonomy over personnel and finance issues.Citation19 To increase income, to compensate for the inadequate investment by local government and to survive, local incentives were put in place to encourage staff to work more effectively and raise revenue. These not only made the staff work harder, but also encouraged them to over-treat and over-prescribe both high technology examinations and medications.Citation18 Areas such as public health and maternal and child health (MCH) care services were neglected because they did not generate a profit.Citation20

The study reported here was part of a larger study on Improving birth outcomes in China: consequences and potentials of policy, state and professional interactions, conducted between 2004 and 2007 in Sichuan and Shanxi provinces.

The data in this paper are from Shanxi Province, an inland area in northern China with a population of 33 million living mostly in mountains and hills.Citation21 In 2006, 40 (34%) and 56 (47%) of the 119 counties in Shanxi were covered by the Decreasing Project, which began in 2005 and the NRCMS programme, which started in 2006, respectively.Citation22Citation23 The hospital birth rate varied from 10–90% across the province.Citation22 On average, the rate increased from 53% in 2000 to 71% in 2004 to 91% in 2007.Citation24Citation25 The MMR in 2006 was 38.8 per 100,000 live births (42.9/100,000 rural, 29.7/100,000 urban).Citation26

Materials and methods

Most of the field work in Shanxi was undertaken between March and December 2006. In the larger study we purposefully sampled three out of the 11 prefectures in which these hospitals were located in the southeast, north and central areas of the province, across high, medium and low MMRs, to allow for diversity of data and range of experiences. In each prefecture, we sampled three counties, one each with high, medium and low MMRs. The MMR of the nine counties sampled varied from 0 to 147.1 per 100,000 live births during 2003–2005. We worked in larger county hospitals and smaller township hospitals. The hospital birth rate in the sampled areas ranged from 52% to 99% in 2005. Data collected in the larger study included two township hospital case studies, medical records (n=1,067), maternal deaths reports (n=40), labour observations (n=8) and a maternal deaths review meeting (n=1), interviews with obstetricians and midwives (n=17), hospital leaders (n=12), MCH workers (n=6) and post-partum women (n=92). Some of these results have been published elsewhere.Citation27–29

The findings reported here drew on the same sampling base with all available women who were residents of the prefectures and had had a home birth within the previous six months and could be contacted through the MCH worker and invited to participate. We managed to interview all the eligible women (n=30) in five of the counties studied. In the other four counties, home birthing women could not be identified either due to the high hospital birth rate (>90%) or lack of support from local MCH workers. In this paper we report on these interviews and draw on the hospital audit data, observations and interviews with local health workers from the larger study to provide additional evidence for our conclusions.

Ethics permission was granted from the Charles Darwin University Human Research Ethics Committee (approval no. H05102) and the Second Hospital of Shanxi Medical University.

All 30 women approached agreed to participate and gave their consent. They were interviewed in their own homes by the first author, a local Chinese medical practitioner, who was undertaking doctoral studies in Australia. Interviews took about 30 minutes each and were recorded in a notebook either during the interview or later the same day. Women were asked about their antenatal care and home birth experiences, and their reasons for not going to hospital to deliver. All 30 women were housewives, 21–39 years of age, and were between the first day and fifth month post-partum at the time of interview. Nine had finished primary school, 16 had finished middle school, one had finished high school, and four had had no schooling. The annual household income among them varied from 1,000–30,000 Yuan (US $127–3,798).Footnote*

The interviews were conducted and analysed in the local Chinese dialect using content analysis. The first author read the texts through several times to obtain a sense of the whole. Codes were attributed subsequently to the units of text that were similar. The results of the content analysis were first discussed with local Chinese senior clinicians to seek verification of interpretation, then translated into English by the first author and discussed with the second author. Agreement was readily achieved on the main categories and sub-categories from the texts. Key illustrative quotes are used to illustrate the complexity of barriers found.

Findings

Hospitals where deliveries took place

Ninety per cent of hospital births in the Shanxi study areas occurred in the county hospitals and less than 10% in township hospitals. Observational data across nine county hospitals showed that birthing women and post-partum women were sharing the same cramped rooms; there were two to eight women per room with at least two family members with each woman, with no curtains for privacy between beds. Babies were with their mothers, mostly in the same bed. Running water was available in all nine county hospitals, but in one the pipe was not connected to the drain and the staff had to use a bucket to collect the waste water. Sterilisation was always available to sterilise medical equipment. Five hospitals did not supply quilts or pillows so women had to bring their own. Women were restricted to a supine birthing position, no pain relief was provided in labour and there was overuse of ultrasound.Citation27 There was at least one county hospital in each county which could provide comprehensive emergency obstetric care; however, the obstetric practice was poor and not evidence-based.Citation28

In the nine counties, few township hospitals (0–7) could provide basic delivery services locally. Of the township hospitals which could provide birthing services, the quality of care was poor, as illustrated in two case studies. The first township hospital was located in a mountainous area. Its catchment population was 15,000, covering 43 villages in 2005. The hospital had not received any funds from government since the 1970s, except to subsidise around 30% of staff salaries. The hospital did not have a labour bed, x-ray machine, ultrasound or telephone. There were three poorly educated “obstetricians” but they could only manage normal vaginal births. For many years, few women came here to deliver; for example, in 2005 they delivered ten babies (7% of the total live births in the catchment area). The second township hospital was located in a town with another township hospital. This was unusual. Despite this, the hospital birth rate of the township was only 39.2% (73/186) in 2005. The township hospital we studied delivered 30 of the 73 babies in 2005. The cost of a normal vaginal birth was about 300 Yuan. The director of the hospital allowed the staff to provide birthing services at women's homes. This was the only hospital we studied that allowed this. Women paid the same price as they would in the hospital but the birth attendants could keep a small proportion as income.

Antenatal care

Antenatal care in a public hospital was not free. The women reported attending an average of 3.3 antenatal visits (range 1–9). Of these, an average of 1.6 visits occurred in a public hospital (both county and township hospitals) while 1.7 visits were to a private provider (including private ultrasound clinics, private village doctorsFootnote* or TBAs). The antenatal care women received was of very poor quality, with many steps missing. Four women did not have their blood pressure measured at all, 16 did not have any abdominal palpation, 18 did not have their haemoglobin tested and 24 never had their urine tested for proteinuria.

The women had ultrasound scans in public hospitals and/or private clinics. Women could easily find a private clinic, pay and have a scan on their own initiative. Private ultrasound clinics, often staffed by retired technicians from local county hospitals, were unregulated and care was problematic. Depending on the reputation of the technician, the cost of an ultrasound in the study areas was 15–40 Yuan. Women placed a higher value on ultrasound than abdominal palpation. The only antenatal care four of the women received was ultrasound scanning. On average the women from the sample who gave birth at home had 2.3 ultrasound scans: two women did not have any, 22 women had between one and three scans, two women had four scans and the remaining four women had five scans.

Women had spent 58.1 Yuan (range 15–185 Yuan) on antenatal care on average, including ultrasound, laboratory tests and physician examinations. Women delivering in hospital tended to spend more money on antenatal care (25–235 Yuan among 62 women in our larger study) because they had more antenatal visits, more blood pressure measurements, more physical examinations, more blood and urine tests and more ultrasound scans.

Illegal births

Of the 30 women interviewed, the current birth was the first for six of the women, the second for 22 and the third for the remaining two. The one-child policy appeared to be less coercive than before and none of the 24 women interviewed avoided hospital birth for fear of being reported for illegal birth. In the larger study our hospital audit data showed that 46.8% of the normal vaginal births sampled were to multiparous women, of whom 6.89% were parity three or above.Citation30

“It is not because of illegal birth [that I gave birth at home], [I am] not frightened, I would not have got pregnant if I was frightened. The family planning policy is not so tight in recent years, nobody comes [to check]. Now, we also don't want to have more children, you can't bring them up even if you have them [because of the expense]. [We] need to pay the fine when we get the child registered in the household, but [we] don't know how much it will be, maybe over 4,000 Yuan. Hiding it does not solve the problem, because you have to come out when you registered in the household. People [family planning cadre] will find out anyway.” (Participant 8, age 30, second birth)

Barriers to hospital birth identified

Financial difficulties

Twenty-six women cited financial difficulty as the biggest barrier for not giving birth in hospital.

“The main reason is family difficulty [no money]; it will cost lots of money in the hospital. Home delivery cost me 200 Yuan; our annual income is 3,000–5,000 Yuan. People say it [hospital birth] will cost more than 1000 Yuan; it is not possible for less than 500 Yuan. No other reasons, mainly economic difficulty.” (Participant 19, age 29, first birth)

Six of the nine counties we studied were covered by the Decreasing Project, which reimbursed women who gave birth in hospital 150 Yuan. The NRCMS programme was also operating in four of the nine counties. Only those women having an authorized birth in hospital, that is a first child, could access the benefit (300 Yuan) from the NRCMS programme. Twenty-four of the women we interviewed would not have received this, even if they had given birth in hospital. They could, however, have received the 150 Yuan from the Decreasing Project.

“If hospital provided a free service, of course we would go to hospital; you know it is safer to be in hospital. However it will cost more than 1,000 Yuan to deliver in hospital. Even though we can have some subsidy from the government, we still need to pay a lot. We village peasants have difficulty earning money, and we don't have that much money to spend.” (Participant 27, age 30, second birth)

Transport issues

In most rural villages buses passed through only a couple of times daily. People who were not within walking distance of a delivery hospital had limited transport options at the time of birth. Of the 11 women who had planned a hospital birth, ultimately five did not go to hospital because of the cost of travel, four because of distance and time, and two because it was at night when there was no transport available.

“It was at midnight, I could not go to hospital. I could not find a vehicle at night. The transportation was not convenient, you know, we live in the mountains.” (Participant 17, age 36, third birth)

Negative experience of hospital delivery and preference for home birth

Ten women expressed “fear of being in hospital” to describe their dissatisfaction with previous experiences of hospital delivery. Of the ten, five linked this to negative staff attitudes, feeling vulnerable at admission and concern at being looked after by a doctor or midwife they had never met before. The hospitals we studied did not provide continuity of care for women but worked in shifts. Therefore women met different doctors for antenatal care and birth, which made them very confused.

“Nobody looks after you [when] giving birth in the hospital. Last time it was between the shift times [when I was delivering], nobody cared [for me], so I was scared to go to the hospital after that. We didn't give [the doctor] a ‘red bag’, so nobody looked after [me]. Only after I found a fellow villager did I find the doctor finally.” (Participant 2, age 25, second birth)

Ten other women had found it troublesome to give birth in the hospital. Some said they needed to bring a blanket and pillow with them because many county hospitals only provided a bare bed. The families also needed to bring simple kitchen implements to cook for the woman post-partum as the hospital did not provide meals. Furthermore, the hospitals had very complicated procedures for admission, payment, giving consent for medical interventions and discharge, so a relative had to act as a “runner” to facilitate all these procedures. At least one relative was also needed to look after the woman on the ward, including overnight, yet no bed or place to sleep was provided for them. Nurses did not provide any care except injections, not even helping women go to the toilet or assisting with breastfeeding as part of their duties. In fact, there were very few midwives on the staff of the hospitals we studied.

In contrast, seven women described home birth as very convenient for themselves and their families. They expressed satisfaction with being at home, having their own belongings around them, remaining in one place, not having to hire a car to go to hospital when labour started and return home afterwards.

Three women reported that the home birth attendant stayed with them throughout labour, whereas in hospital, the doctor or midwife would go home when their shift finished or were often distracted by other duties and continuity of care was interrupted.

Hospital delivery not considered necessary

Six women thought it was not necessary to go to hospital for a second birth as it would be much easier than the first one. It appeared that women were more confident in themselves to deliver successfully if they had had a normal birth before.

“In our village, we only go to hospital for the first birth. The second birth generally will be delivered at home.” (Participant 27, age 30, second birth)

“My first baby was delivered in hospital, it went smoothly. Besides, I had two antenatal check-ups for this one, and everything looked good. Also I didn't have the money, so I did not go to hospital this time.” (Participant 29, age 33, second birth)

“Ultrasound showed the baby was in the right position so it would be easy. If it was not easy, I would have had to go to the hospital in spite of the high cost.” (Participant 3, age 27, second birth)

“We only go to hospital when ultrasound shows the baby is not in the right position.” (Participant 5, age 30, second birth)

Home birth attendants

In the study areas, hospital birth was strongly promoted using slogans and other written materials. The practice of home birth was illegal and TBAs were openly criticized by the health system. In all study areas, the TBAs' licences were cancelled by the provincial government between 2003 and 2005. However, TBAs were still very welcome in the villages, because they provided a cheaper service with better continuity of care for women. Of the 30 women interviewed, 22 were attended by TBAs who were practising despite government regulations.

“I have known her [TBA] for many years. She has more than 30 years of birth experience and we all trust her.” (Participant 22, age 31, second birth)

“We live close to each other. She [TBA] gave me free antenatal care at her home; accordingly I asked her to help me with the birth.” (Participant 6, age 31, second birth)

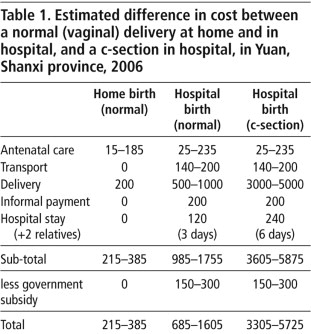

Costs of antenatal care plus home vs. hospital delivery

As shown in Table 1, if a woman had a normal delivery at home it was far less expensive than if she delivered in hospital. Hospital delivery in the study areas was much more expensive as it involved more antenatal tests, informal payments, transport costs and more expensive daily allowances while in hospital, including to cover the cost of relatives staying with the woman.

A c-section was even more expensive. The c-section rates in 2005 in the five rural hospitals which located in the five counties where women were interviewed were 6.8%, 14.8%, 19.3%, 21.0% and 40.8% respectively. The highest rate we found in the larger study was 66.7% in one hospital. In the rural areas, c-section was mostly an emergency procedure, not least because of the cost.

The government's subsidies for hospital delivery of 150 from the Decreasing Project and another 300 from the NRCMS programme if it was the first birth were far less than women needed, and would not have been sufficient for women on low incomes. Indeed, where the annual household income was as low as 1,000 Yuan, a normal delivery in hospital, let alone a c-section, would have caused huge financial difficulties. Even with an annual income of 30,000 Yuan, the highest among the 30 women interviewed, a c-section would have cost as high as 19% of their annual income.

Discussion and recommendations

To our knowledge, this study is the first to explore the experience of women who gave birth at home in a rural Chinese province and provides useful insights into the lack of quality of care in maternity services and the multiple barriers that prevented women from going to hospital to deliver their babies. Our observations in hospitals in Sichuan province in the larger study confirm these findings from Shanxi,Citation27 which can help to inform the organization and provision of services in future.

“Financial difficulty” was identified as the biggest barrier for women to access hospital childbirth services. Other international studies have also shown that utilization of hospital services for birth is associated with women's economic status.Citation31Citation32 In China, access to hospital services is significantly influenced by the household income. Women without regular income and health insurance have tended to avoid using hospital services.Citation33 Privatization of health services in China, given the absence of adequate health insurance or reimbursement for most rural women, means they have to pay out of their own pockets. In both Shanxi and Sichuan provinces, most women who gave birth in hospital had to pay the “red bag” to the physician managing the birth,Citation27 creating an extra financial burden for women.

We found that rural women were not frightened to go to hospital with an “illegal” birth, in contrast with studiesCitation34–37 which found that family planning policy was applied very strictly and deterred women from using maternity services for fear of punishment. Our study sample was small and may not have captured the full picture, but these other studies took place before 2000 and also do not reflect the situation in 2003–2005, when the family planning policy was changing. Our sample was also an unusual one, and arguably remote from strict monitoring. In our study areas, the policy was characterised by forcing women to pay a fine rather than have an abortion.

Women who have good antenatal care are more likely to use facilities for delivery.Citation32 In our study most home birthing women received very poor antenatal care, and many important aspects of care were missing, with ultrasound being the only consistent item of care received. This is consistent with findings from rural Anhui province.Citation38

Although some women took it for granted that a “normal” ultrasound meant a “normal” delivery, a Cochrane review has shown that while ultrasound at 18–20 weeks of pregnancy is useful for dating, and for detecting multiple pregnancy, most fetal abnormalities and the position of the placenta, it cannot predict a normal birth or guarantee better birth outcomes either for babies or mothers.Citation39 There is a need to educate rural women (and perhaps staff as well) about what ultrasound can and cannot do. Ultrasound was used excessively in both provinces we investigated. In Sichuan, in one county hospital, women were routinely scanned (and charged) after birth to check if the placenta and membranes had been expelled completely.Citation27 Unnecessary scans appeared to be related to income generation, especially for salaries of private providers and clinics.Citation40 This has also been found in Viet Nam, where the belief that ultrasound scans are considered “modern” and therefore a sign of quality of care, also contributed to overuse.Citation41

Transport was a huge challenge for the women in our study, especially at night. Many studies have found that lack of transport deters women from delivering in hospitals, particularly when labour starts at night unexpectedly.Citation42–44 Except for one township hospital we studied, doctors were not allowed to provide delivery services outside of hospitals, for fear that hospitals might lose the income. But in a situation where women could not get to a hospital, cancelling local TBAs' licences would not make it easier for women to get any skilled help, especially those living in remote mountainous areas. Giving the government's concern about the limits of TBAs' skills, it should consider the alternative of encouraging hospital doctors and midwives to provide maternity outreach services for those women who have difficulty reaching a hospital, to ensure every woman has a skilled birth attendant regardless of place of birth. In remote areas, as has occurred in one of our minority study areas in Sichuan province,Citation45 TBAs could be integrated into the health system through appropriate education and support. In this role, they extend the health system. However, transport barriers, especially in case of obstetric emergencies, are still an issue and can perhaps only be overcome by providing free transport.

The quality of county and township hospital services urgently needs to be improved. Township hospitals need to be updated to provide basic, accessible and affordable birthing services. These can be linked to county hospitals by ambulance for improved emergency care. There is a need to renovate run-down buildings, replace old equipment and help to retain qualified staff by providing adequate salaries that do not need to be “topped up” through informal payments, which should be stopped. Finally, to increase the hospital birth rate for poor, rural and remote women, the government needs to provide sufficient levels of financial support and incentives through the Decreasing Project and NRCMS programme.

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our thanks to all the women and health workers who agreed to be interviewed. This research was supported by the project “Improving birth outcomes in China: consequences and potentials of policy, state and professional interactions” (LP0454943,) jointly funded by the Australian Research Council, Second Hospital of Shanxi Medical University and Western China Second Hospital Sichuan University.

Notes

* Based on the exchange rate at the time of the study.

* Village doctors (called barefoot doctors before 1985) are lay persons with 3–6 months basic medical training in a county or community hospital. They receive almost no ongoing training. Currently their role is to collect data for the Family Planning Committee and township hospital, including number of live births, place of birth (home or hospital), number of maternal and infant deaths, and deaths of children under five. Some also do deliveries for women at home, often in villages with no TBA.

References

- OM Campbell, WJ Graham. The Lancet Maternal Survival Series steering group Strategies for reducing maternal mortality: Getting on with what works. Lancet. 368(9543): 2006; 1284–1299.

- State Council of the People's Republic of China. The Program for the Development of Chinese Women (1995–2000). Beijing; 1995.

- S Wang. Maternal deaths causes in Xinzhou City in 2006 [in Chinese]. Proceeding of Clinical Medicine Journal. 16(11): 2007; 1094–1095.

- X Li. Analysis of the causes for maternal deaths in poor mountainous areas [in Chinese]. Maternal & Child Health Care of China. 22(24): 2007; 3341–3342.

- M Wu, Q Song. Investigating the causes for maternal deaths in 1996–2005 [in Chinese]. Maternal & Child Health Care of China. 23(3): 2008; 399–400.

- B Chen. Strategies and causes for maternal deaths in poor areas [in Chinese]. Health Vocational Education. 25(18): 2007; 120.

- C Li, Y Wu, J Liang. Influence of social factors on the maternal mortality rate in the rural areas [in Chinese]. Modern Preventive Medicine. 34(6): 2007; 1019–1021.

- Y Chen, J Wang, L Che. Taking the New Rural Cooperation Medical Scheme as a terrace to strengthen the health care of women and children in villages [in Chinese]. Yi Xue Yu Zhe Xue (Ren Wen She Hui Yi Xue Ban). 27(8): 2006; 4–7.

- Y Zhu, T Zhou. Ministry of Health: “Decreasing” project will cover 300 million in 2005 [in Chinese]. Beijing, China; 2005. At: <http://politics.people.com.cn/GB/1027/3163685.html>. Accessed 19 March 2007

- L Huang. Illegal home birth in rural areas and the countermeasures [in Chinese]. Zhong Guo Chu Ji Wei Sheng Bao Jian. 17(11): 2003; 44.

- X Deng. Strengthen the management of village birth attendants and improve hospital birth rate [in Chinese]. Maternal & Child Health Care of China. 15(3): 2000; 145–146.

- State Council of the People's Republic of China. The Measures for Implementation of the Law of the People's Republic of China on Maternal and Infant Health Care. 2001; State Council of the People's Republic of China: Beijing.

- A Wang. Regulate the issue of Birth Certificate, promote designated hospital birth, improve hospital birth rate [in Chinese]. Maternal & Child Health Care of China. 15(11): 2000; 675.

- China Ministry of Health. Chinese Health Development Report Series. 2008; Ministry of Health, China: Beijing[updated]. At: <http://61.49.18.102/12.htm>. Accessed 16 October 2008

- J Liang, Y Wang, J Zhu. Analysis of the relationship between maternal mortality rate and supportive indexes [in Chinese]. Maternal & Child Health Care of China. 24(10): 2009; 1313–1316.

- J Liang, J Zhu, M Li. Analysis of the epidemiological characteristics of maternal mortality in counties covered by the ‘Decreasing Project’ in 2007 [in Chinese]. Modern Preventive Medicine. 36(10): 2009; 1851–1853.

- A Wagstaff, M Lindelow, S Wang. Reforming China's Rural Health System. 2009; World Bank: Washington, DC.

- Y Liu, WCL Hsiao, Q Li. Transformation of China's rural health care financing. Social Science & Medicine. 41(8): 1995; 1085–1093.

- J Fang. Health sector reform and reproductive health services in poor rural China. Health Policy and Planning. 19(Supplement 1): 2004; i40–i49.

- Z Dong, MR Phillips. Evolution of China's health-care system. Lancet. 372(9651): 2008; 1715–1716.

- Bureau of Statistics of Shanxi. The gap of per capita GDP is shrinking between Shanxi and national level [in Chinese]. 2007; Bureau of Statistics of Shanxi: TaiyuanAt: <www.stats-sx.gov.cn/tjfx/fxbg/200711300006.htm>. Accessed 24 February 2008

- Z Guo. Decreasing maternal mortality ratio, eliminating newborn tetanus project management [in Chinese]. 2005; Shanxi Province: Taiyuan.

- Shanxi Provincial Government. Working report on pilot counties of new rural cooperative medical insurance in Shanxi Province [in Chinese]. 2006; Shanxi Provincial Government: TaiyuanAt: <www.sxws.cn/sanitation/web/hotspot/NewCountry/Show.aspx?fid=725&lei=8>. Accessed 20 March 2007

- Shanxi Provincial Women and Children Working Committee, Shanxi Provincial Statistics Bureau. Shanxi Province Women and Children Development Surveillance Report in 2007 [in Chinese]. Taiyuan; 2008.

- Y Bai, Q Wang. Evaluation of decreasing maternal mortality ratio, implementing the ‘Women and Children Development Program’ in Shanxi Province [in Chinese]. Lin Chuang Yi Yao Shi Jian Za Zhi. 14(11): 2005; 841–843.

- Q Wang, Y Ma. Analysis of the maternal deaths in 2006 in Shanxi Province [in Chinese]. Shanxi Yi Yao Za Zhi. 36(7): 2007; 607–608.

- A Harris, Y Gao, L Barclay. Consequences of birth policies and practices in post-reform China. Reproductive Health Matters. 15(30): 2007; 114–124.

- Y Gao, L Barclay. Availability and quality of emergency obstetric care in Shanxi Province, China. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics. 110(2): 2010; 181–185.

- Y Gao, S Kildea, L Barclay. Maternal mortality surveillance in an inland Chinese province. International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics. 104(2): 2009; 128–131.

- Gao Y. A study of accessibility, quality of services and other factors that contribute to maternal death in Shanxi Province, China. Doctoral thesis, Charles Darwin University; 2008.

- S Dhakal, GN Chapman, PP Simkhada. Utilisation of postnatal care among rural women in Nepal. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth. 7(19): 2007; 10.1186/471-2393-7-19.

- S Gabrysch, O Campbell. Still too far to walk: Literature review of the determinants of delivery service use. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth. 9(34): 2009; 10.1186/471-2393-9-34.

- G Bloom, S Tang. Health Care Transition in Urban China. 2004; Ashgate Publishing, Ltd.: Aldershot.

- H Ding, L Zhang. Analysis of national maternal mortality from surveillance data [in Chinese]. Zhonghua Fu Chan Ke Za Zhi. 34(11): 1999; 645–648.

- Y Zeng, Z Hu. Inquire into the non-medical factors on maternal deaths in poor mountainous areas [in Chinese]. Practical Preventive Medicine. 9(2): 2002; 174.

- JP Doherty, EC Norton, JE Veney. China's one-child policy: The economic choices and consequences faced by pregnant women. Social Science & Medicine. 52(5): 2001; 745–761.

- SE Short, F Zhang. Use of maternal health services in rural China. Population Studies. 58(1): 2004; 3–19.

- Z Wu, K Viisainen, X Li. Maternal care in rural China: a case study from Anhui province. BMC Health Service Research. 8(55): 2008; 10.1186/472-6963-8-55.

- M Whitworth, L Bricker, JP Neilson. Ultrasound for fetal assessment in early pregnancy. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (Online). 4: 2010(Art. No.: CD007058): 10.1002/14651858.CD007058.pub2.

- X Liu, T Martineau, L Chen. Does decentralisation improve human resource management in the health sector? A case study from China. Social Science & Medicine. 63(7): 2006; 1836–1845.

- T Gammeltoft, HT Nguyen. The commodification of obstetric ultrasound scanning in Hanoi, Viet Nam. Reproductive Health Matters. 15(29): 2007; 163–171.

- DV Duong, CW Binns, AH Lee. Utilization of delivery services at the primary health care level in rural Vietnam. Social Science & Medicine. 59(12): 2004; 2585–2595.

- M Mrisho, JA Schellenberg, AK Mushi. Factors affecting home delivery in rural Tanzania. Tropical Medicine & International Health. 12(7): 2007; 862–872.

- P Griffiths, R Stephenson. Understanding users' perspectives of barriers to maternal health care use in Maharashtra, India. Journal of Biosocial Science. 33(03): 2001; 339–359.

- A Harris, Y Zhou, H Liao. Challenges to maternal health care utilisation among ethnic minority women in a resource poor region of Sichuan Province, China. Health Policy and Planning. 25(4): 2010; 311–318.