Abstract

Abstract

In 2007, first trimester abortion was legalized in Mexico City, and the public sector rapidly expanded its abortion services. In 2008, to obtain information on the effect of the law on private sector abortion services, we interviewed 135 physicians working in private clinics, located through an exhaustive search. A large majority of the clinics offered a range of reproductive health services, including abortions. Over 70% still used dilatation and curettage (D&C); less than a third offered vacuum aspiration or medical abortion. The average number of abortions per facility was only three per month; few reported more than 10 abortions monthly. More than 90% said they had been offering abortion services for less than 20 months. Many women are still accessing abortion services privately, despite the availability of free or low-cost services at public facilities. However, the continuing use of D&C, high fees (mean of $157–505), poor pain management practices, unnecessary use of ultrasound, general anaesthesia and overnight stays, indicate that private sector abortion services are expensive and far from optimal. Now that abortions are legal, these results highlight the need for private abortion providers to be trained in recommended abortion methods and quality of private abortion care improved.

Résumé

En 2007, Mexico a légalisé l'avortement du premier trimestre et le secteur public a rapidement élargi ses services d'avortement. En 2008, pour connaître les conséquences de la loi sur les services d'avortement du secteur privé, nous avons interrogé 135 médecins travaillant dans des centres privés, choisis au moyen d'une recherche exhaustive. Dans leur grande majorité, les centres proposaient un éventail de services de santé génésique, dont l'avortement. Plus de 70% utilisaient encore la dilatation et le curetage ; moins d'un tiers proposaient l'aspiration par le vide ou l'avortement médicamenteux. Le nombre moyen d'avortements par centre n'était que de trois par mois ; rares étaient ceux qui pratiquaient plus de dix avortements mensuels. Plus de 90% ont affirmé qu'ils assuraient des services d'avortement depuis moins de 20 mois. Beaucoup de femmes choisissent encore d'avorter dans le privé, en dépit de la disponibilité de services gratuits ou peu coûteux dans les établissements publics. Néanmoins, la poursuite de l'utilisation de la méthode par dilatation et curetage, les honoraires élevés (moyenne de $157–505), la prise en charge médiocre de la douleur, l'utilisation superflue des ultrasons, de l'anesthésie générale et de l'hospitalisation indiquent que les services d'avortement du secteur privé sont coûteux et loin d'être de qualité optimale. Maintenant que l'avortement est légal, ces résultats montrent qu'il faut former des prestataires privés aux méthodes recommandées d'avortement et améliorer les soins dans le secteur privé.

Resumen

En el año 2007, se legalizó el aborto en el primer trimestre en el Distrito Federal de México y el sector público rápidamente amplió sus servicios de aborto. En 2008, para obtener información sobre el efecto de la ley en los servicios de aborto del sector privado, entrevistamos a 135 médicos que trabajaban en clínicas privadas, localizadas mediante una búsqueda exhaustiva. En la gran mayoría de las clínicas se ofrecía una variedad de servicios de salud reproductiva, incluso abortos. En más del 70% aún se practicaba el procedimiento de dilatación y curetaje (D&C); en menos del 33% se ofrecía aspiración por vacío o aborto con medicamentos. El número promedio de abortos por cada establecimiento de salud era sólo tres al mes; pocos documentaban más de 10 abortos mensuales. Más del 90% relataron que llevaban menos de 20 meses ofreciendo servicios de aborto. Muchas mujeres aún acuden a servicios de aborto privados, a pesar de la disponibilidad de servicios gratuitos o de bajo costo en establecimientos públicos. Sin embargo, el uso continuado de D&C, los altos precios (una media de $157–505), las deficientes prácticas de manejo del dolor, el uso innecesario de ecografía, anestesia general y estancias de un día para otro, indican que los servicios de aborto del sector privado son caros y distan mucho de ser óptimos. Ahora que la interrupción del embarazo es legal, estos resultados destacan la necesidad de capacitar a los prestadores de servicios de aborto privados en los métodos de aborto recomendados y de mejorar la calidad de dichos servicios.

The legalization of first trimester abortion at women's request in Mexico City on 27 April 2007 marked a major milestone in the advancement of women's reproductive health and rights. Abortions performed in a legal environment are significantly safer than in a restricted framework,Citation1 and when abortion is legal, more women feel able to seek abortion,Citation2 and access may be improved through more open communication about services in the media and on the internet, and greater availability of services.Citation3

During 2008, the public health sector, under Mexico City's Ministry of Health, carried out 13,057 legal abortions,Citation4 compared to 66 abortions between 2002 and 2007, when the legal indications were restricted to rape, danger to the woman's life and health and congenital malformations – a dramatic increase since legalization. However, induced abortions are still being provided by non-governmental organizations and both skilled and unskilled private practitioners, or induced by women themselves, often using medications obtained from pharmacies.Citation5 Before the law changed, these were mostly the only choice for women who needed an abortion; however, there are no data about them since they operated in illegal circumstances. One year after legalization, there was still little known about the number of abortions, type of services or quality of care in the private sector. We therefore decided to carry out a study of the services being provided by a sample of private physicians in Mexico City, to get a picture of the private abortion sector and the effect of legalization on it.

The private sector is a significant source of reproductive health services in Mexico, where private facilities make up 13% of all registered health facilities. The number of physicians in the private sector rose by more than 32% between 2001 and 2005, to approximately 12,900 doctors.Citation6 The National Health and Nutrition Survey of 2006 found that in the 15 days prior to interview, 37.5% of 48,600 Mexicans households sampled had sought some kind of private health service.Citation7 Information on births registered at private facilities also provides evidence of the importance of the private health sector, particularly in the main urban areas. During 2008, out of a total of 199,060 births in Mexico City, 19% were registered by private health facilities. Nationally, 15% of 2,636,110 births were reported by private providers.Citation8 Furthermore, users' perceptions are that quality of care is often better in private services than public ones.Citation7 However, despite the importance of the sector and the existence of a health information reporting system that is compulsory for all public and private facilities,Citation9 data on specific services provided in the private sector are considered anecdotally to be incomplete and often unreliable, and may differ from state to state.

Immediately after the abortion law changed, at the end of April 2007, the city's Ministry of Health started providing first trimester abortions free of charge to the estimated 43% of women residing in Mexico City with no public health insurance.Citation10 Women residing outside Mexico City and women covered by any federal government health insurance (e.g. the Instituto Mexicano de Seguridad Social, Instituto de Seguridad Social para Trabajadores del Estado, Petroleos Mexicanos and other smaller insurers)Citation11 are required to pay a service fee, on a sliding scale based on income. Thus, while many abortions are provided at no cost in the public sector, most are still subject to some user fees.

In addition, women seeking legal abortion at public sector facilities may face difficulties navigating a somewhat complex intake process, and may fear being questioned about their decision.Citation3 Previous studies on barriers to legal abortion services in Mexico have shown that women who were pregnant due to rape faced many difficulties in seeking a legal abortion in the public sector.Citation12Citation13 Other research has documented insensitive staff attitudes toward patients, even for miscarriage and post-abortion care.Citation14 Experience from South Africa, where abortion was legalized in the 1990s and introduced in public sector abortion services, suggests that women may avoid public services for fear of staff attitudes, ignorance about the law, lack of information on where to access services, and fear of breaches in confidentiality.Citation15 Furthermore, adolescents may seek private abortion services hoping to avoid burdensome requirements, e.g. parental consent, in public facilities.

We wanted to know whether these and other factors were driving women in Mexico City to continue seeking private abortion services despite the availability of low-cost, safe, legal abortion services in the public sector.

Since the change in the law, Mexico City's Ministry of Health has collected and disseminated information on the number of publicly-provided abortions services, the type of procedures (surgical and medical) and demographic characteristics of women having abortions. Mandatory reporting has not been extended to private sector abortions, however, and there is therefore no centralized information on them. In order to start to fill this gap, in this study we collected primary data on the number of abortions, provided by a sample of 135 private sector physicians, and their cost and quality, in Mexico City in August–December 2008.

Methods

This was a descriptive study. There is no list of all private abortion providers in Mexico, and not all abortion providers publicly advertise their services. The methodology we used did not pretend to and was not able to identify a representative sample of such providers. We implemented a multi-stage sampling technique designed to identify potential formal health sector providers, to confirm whether they actually provided abortion services, and if so, to interview them. As a first step, we examined public advertisements, including from the internet, the telephone directory, the printed yellow pages and magazines. Internet sites used to search for abortion services included Google, Yahoo!, and MSN with the keywords: abortion, pregnancy, help, woman, pregnancy termination, doctor, physician, gynaecologist, gynaecology, obstetrics, women's services, help for women, women's health, clinic and hospital. Virtually all providers identified in this way posted only their phone number and e-mail address on the internet, not their location. We also checked websites and forums where legal abortion information was provided, as some of these sites included contact information for private abortion providers. Furthermore, we searched the online Yellow Pages (October 2007–September 2008 edition) for legal abortion services, doctors, and gynaecology and obstetrics clinics. Only one listing explicitly advertised abortion services, but more than 600 other listings were found for doctors providing services in obstetrics and gynaecology. We also obtained a list of doctors at seven major private hospitals that were known to offer post-abortion care.

We searched 23 different newspapers on the Monday, Thursday and Sunday of the first week of March 2008, which yielded very little, and all the newspapers registered at the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de Mexico, reviewing those published in the second two weeks of January 2008 and the first two weeks of June 2008. Most of the advertisements relevant to our search were concentrated in only three newspapers. We also searched magazines on television programming, soap operas and fashion, a magazine for women in their 20s, and another for adolescents. However, we did not find a single abortion advertisement in these magazines.

To try to locate small clinics that could not afford or chose not to advertise in magazines and newspapers, we searched advertisements posted in and around the public transport system, including bus and subway stops in the seven major stations where several subway lines converge. This yielded only four advertisements for abortion services. Altogether, these searches yielded 3,233 contacts.

Finally, we did a search for advertisements in a sample of streets of different areas of the city, based on population density, in the 16 administrative sub-divisions (delegaciones) of which Mexico City is comprised. We focused on lower middle-class neighbourhoods, where there are an abundance of small health facilities serving the community. In this way, we located 115 health facilities spread throughout the 16 delegaciones, giving a total list of 3,348 potential providers as contacts.

To find out whether these providers actually offered legal abortion services, we made direct telephone enquiries to all 115 health facilities and “mystery client” phone calls to a random sample of 581 of the other 3,233 contacts. This first call, which any health provider working at the facility could have answered, was conversational and only loosely scripted, to solicit the following information: whether abortion services were provided, which abortion methods were used (medical, surgical or vacuum aspiration), approximate cost, upper time limit, required laboratory tests, and verification of the address and contact information. It is important to mention that the information generated through these calls only served as a filter to identify actual abortion providers, and the responses are not included here.

These phone calls generated a list of 159 confirmed abortion providers: 46 of the 115 clinics identified in the streets and 113 from the sample of 581. Of these 159 confirmed contacts, we conducted in-depth, face-to-face interviews with the 135 providers who agreed, from 39 out of the 46 street-identified clinics and 96 of the 113 confirmed abortion providers in the rest of the sample (acceptance rate 85% in both samples). We interviewed one provider at each site.

In order to protect the confidentiality of these providers, we conducted the interviews at their clinics. Compensation was offered to all providers for their time; some accepted, while others preferred to provide the information for free. We obtained informed consent from each provider. Interviews included information on characteristics of the provider and their facilities; services offered, costs and requirements, e.g. laboratory tests and upper time limit; knowledge of Mexico City's abortion law and guidelines, and their perceptions of the impact of legalization on the demand for services and on the practice of legal abortion. The interviews were conducted between August and December 2008. The findings presented here are from the face-to-face interviews with the 135 physicians who confirmed they were direct abortion providers.

Findings

Characteristics of physicians and facilities

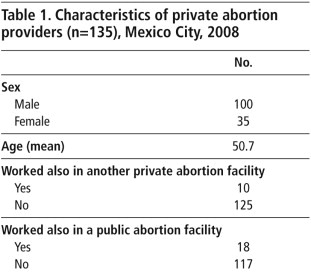

Seventy-four per cent of the respondents were male and 26% female (Table 1). The average age was 51. Most of them did not work in another public or private clinic or hospital. Just under half were obstetrician–gynaecologists, 24% had another specialty and the rest were general physicians. Mean duration of professional practice was 19 years (SD 8 years).

All but five or six of the facilities had an interdisciplinary team consisting of a mean of 5 obstetrician-gynaecologists, 8 other physicians, 3 surgeons, 4 anaesthetists, 11 nurses and other support staff. All facilities had consultation rooms, 74% had operating rooms, 33% included a laboratory and 22% had their own ambulance. All the facilities provided antenatal care and 86% offered delivery care; over 90% provided treatment for sexually transmitted infections, screening for cervical and breast cancer, and contraception, including emergency contraception; 77% offered sterilisation (data not shown).

Abortion methods

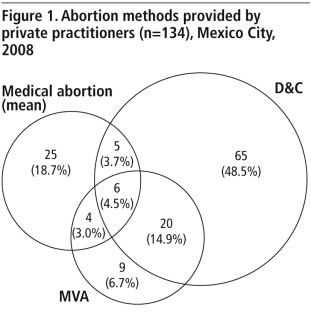

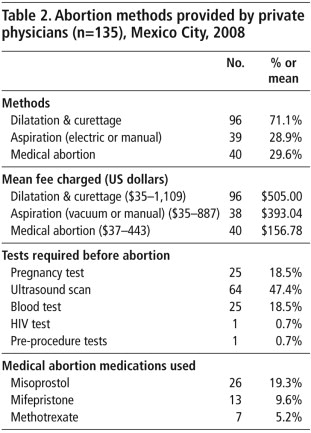

Questions were almost exclusively related to first trimester abortion techniques. 71% of providers in our sample used dilatation & curettage (D&C). Less than a third provided manual or electrical vacuum aspiration (MVA, EVA) and/or medical abortion pills (MA) (Table 2, ). There was some overlap in the methods offered, but only one in 20 providers was trained in and able to provide all these techniques. Just under 20% offered only medical abortion using either misoprostol alone, mifepristone + misoprostol, or methotrexate + misoprostol.

Twenty-five of the 135 providers requested a pregnancy test before performing an abortion, and 64 required an ultrasound. Among those doing D&C, 84% required the woman to spend at least one night in the clinic, while 54% did so even after MVA. None reported the need for hospitalization in the case of medical abortion. Reported pain management given was generally inadequate (data not shown): 20% performed D&C with local anaesthesia; aspiration was performed with general anaesthesia by 49% of providers, while 10% did not provide any pain management with MVA. One in four providers who gave medical abortion did not prescribe any pain medication either, and a significant proportion of those who did only prescribed paracetamol (ibuprofen being the preferred pain medication for MA). Follow-up of one or two visits was booked in 83% of cases after D&C, 87% after MVA and 95% after MA, while telephonic follow-up only was offered in 7.5%, 9% and 13%, respectively (data not shown).

Fees charged

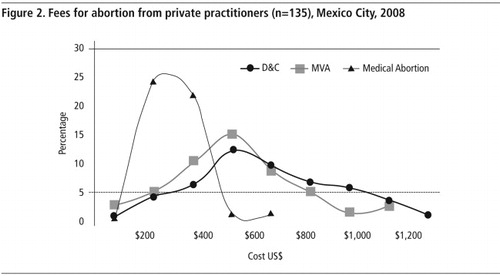

Fees charged ranged from a minimum of US$35 to a maximum of US$1,109Footnote* (Table 2, ), and varied depending on the method and the clinic. D&C was most expensive, with a mean price of US$505, followed by MVA at US$393 and medical abortion at US$157. We did not ask whether the fee scale was linked to other variables, such as gestational age.

Grounds for abortion, counselling and support

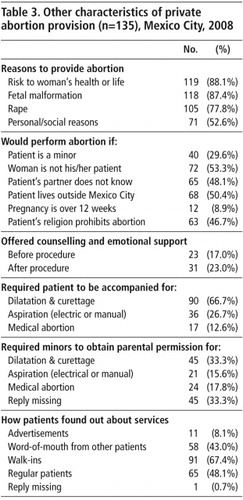

Grounds for which providers reported performing abortions included risk to the woman's health or life (88%), congenital malformations (87%), rape (78%), and personal/social reasons (53%) (Table 3). Approximately 50% offered abortions only to their regular patients, and the same proportion only for women residing in Mexico City; less than one-third said they would provide an abortion to a minor, and only 9% if the pregnancy exceeded 12 weeks (still legal under Mexico City law following rape, risk to woman's health or life, or severe fetal malformation).Citation16 A majority of providers required the patient to be accompanied to the facility by another adult for D&C (67%), while only 27% and 13% required this for aspiration and medical abortion, respectively. Of those who would provide an abortion to a minor, approximately one in three required parental permission. When asked how patients found out about their services, 67% responded through walk-ins and 8% through advertisements.

Only 8% said they suggested alternatives to abortion, such as adoption, or tried to dissuade women from having an abortion, while 77% said they simply explained the procedure and/or how the medication works, but did not try to influence the woman's decision (data not shown). Only 15% said they provided counselling if the women needed help to make the decision, and 23% offered some kind of emotional support afterwards.

Knowledge about the new law and guidelines since legalization

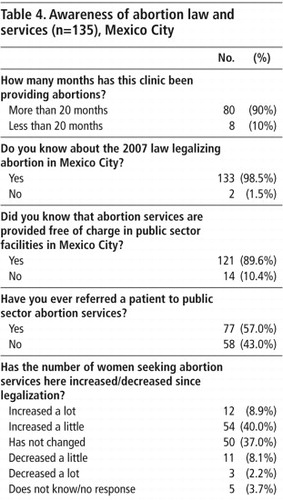

In a final set of questions, we asked providers about the new abortion law and any perceived changes in their patient volume and practices since it had changed (Table 4). More than 90% of the providers reported that they had been offering abortion services for less than 20 months (abortion was legalized less than two years prior to our survey). Only two of the 135 providers said they did not know that Mexico City had passed a law legalizing abortion, 62% said they felt safer in the present legal circumstances and only one had been targeted by anti-choice activities.

Almost 90% knew that abortions were provided free of charge in public facilities in Mexico City, and 57% reported having referred women to these facilities. Forty-nine per cent reported that the number of women seeking abortion services at their facilities had increased since legalization, while 10% reported that the demand had decreased. On average, about two women per month sought abortion services at their facility before legalization and this had increased to about three afterwards. However, only 5% reported more than ten abortions per month at the time of the interview.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to investigate private abortion services since abortion was legalized in Mexico City, and we were able to identify a large number of private facilities. Even though the vast majority of these providers carried out a small number of abortions per month, and often only for their regular patients, the estimated total number of abortions obtained privately may be significant. If, as with our sample, at least one in five of the more than 3,000 private facilities identified in Mexico City were doing three abortions per month, then the private sector was doing some 21,600 induced abortions annually. In comparison, approximately 13,000 women had an abortion in public health facilities in 2008;Citation4 overall between April 2007 when the law changed and the end of August 2010, 45,000 abortions were reported in the public sector.Citation17 A recent study estimated that there are approximately 100,000 abortions annually in Mexico City, suggesting that most abortions are carried out either in the formal or informal private sector.Citation18

The profile of most of the abortion providers in this study suggests that they function as the woman's family doctor/gynaecologist and provide her with a range of other reproductive and sexual health services, from contraception to reproductive cancer screening, and antenatal care to delivery. Awareness of the 2007 law reform is high. However, due to the sensitivity of the question, we did not ask directly whether the change in the law prompted these providers to offer legal abortions and refer women to colleagues, or simply allowed them to disclose their previous practices. In fact, only one in ten respondents said they had already been providing abortions prior to legalization. One in two said, however, that the number of women requesting abortion had increased since legalization.

It is well known that making abortion safe requires good laws, policies and programmes, and good health service provision. Any transition from unsafe to safe services, public or private, needs an organized effort to train new providers and open services. Such a transition should be based in best practice; mindful of women's needs; rooted in public awareness of the existence of these services; and ensure access to all women, including those with special needs, such as adolescents, single women and women seeking later abortions.Citation19Citation20

While it was beyond the scope of this research to ascertain the total number of abortions in the private sector, our study suggests that many women are still accessing private abortion services and may keep doing so, because these are their regular doctors anyway. However, their reasons may also include expectation of a better quality of care in the private system, absence of bureaucratic hurdles and conscientious objectors, lack of awareness of the new law and privacy concerns.Citation5,15,21

Studies of clandestine services pre-legalization generally focus on issues related to access and women's perspectives.Citation5,13,19–21 More recently, much attention has been paid to evaluate Mexico City's public facilities, where efforts have been successfully focused on improving quality of care, methods used and providers' attitudes.Citation4,22

Some other aspects of our findings are worth highlighting. First, the cost of a private abortion was high and the use of D&C, ultrasound and general anaesthesia, along with keeping women in the clinic overnight, contributed to this. Moreover, the quality of services appeared to be far from optimal in many cases. Over 70% of providers were still doing D&Cs, which WHO stopped recommending many years ago. Less than one in three used MVA or medical abortion. Pain management was often not available at all or what was offered was not the best option, general anaesthesia was used unnecessarily, and information provided before and after the procedure appeared in some cases to be limited. This all suggests the need for better training of private abortion providers, but their mostly very low caseloads creates little personal incentive for them to seek further training; other means and strategies may need to be found.

The fact that 90% of our sample said they had started offering abortion services only after the law had changed suggests that legalization may actually have led to an increase in abortion providers; alternatively some of these providers may simply be reluctant to admit they had been providing abortions before legalization. Additionally, the fact that one in five providers offered only medical abortion may suggest that there are new abortion providers who are becoming confident, now that it is legal, to offer this alternative to their patients.

There were several limitations to this study. First, we studied only formal private facilities, where physicians provide the services. It is probable that we missed poorer quality providers, who do not advertise in the yellow pages or elsewhere, who work in facilities in the poorest parts of the city, with less infrastructure and human resources, who may comprise a significant part of existing private facilities all over the country.Citation23 Finally, since abortion is still highly stigmatized in Mexico and concerns about breaking the law may still exist, there may have been under-reporting on some of the questions, particularly in regard to services before the law changed.

We believe all abortion providers, public and private, should regularly report data on the abortions they provide to the relevant authorities. We recommend that all abortion providers should be trained and certified in WHO-recommended abortion methods, including medical abortion, be advised to adopt adequate and appropriate pain management protocols, and eliminate routine overnight stays and use of general anaesthesia for aspiration abortions. All these are evidence-based best practices that can improve the quality and safety, and reduce the cost of private as well as public abortion services.

Notes

* The exchange rate in December 2008, used for all US$ figures in the paper, was US$1=13,5225 Mexican pesos.

References

- S Sing, D Wulf, R Hussain. Abortion Worldwide: A Decade of Uneven Progress. 2009; Guttmacher Institute: New York.

- LH Kahane. Anti-abortion activities and the market for abortion services. American Journal of Economics and Sociology. July: 2000; 3–4.

- Troncoso E, Palermo T, Ortiz O. Barriers to legal abortion services in Mexico City: women's perspectives. Presented at American Public Health Association, 137th Annual Meeting. 7–11 November 2009.

- P Sanhueza. Experiencias de la Secretaria de Salud del Distrito Federal con el Programa de Interrupción Legal del Embarazo. G Freyermuth, E Troncoso. El aborto: acciones médicas y estrategias sociales. 2008; Comité por un Maternidad Sin Riesgos and Ipas: Mexico City.

- DL Billings, D Walker, G Mainero del Paso. Pharmacy worker practices related to the use of misoprostol for abortion in one Mexican state. Contraception. 79(6): 2009; 445–451.

- Sistema Nacional de Información en Salud. Dirección General de Información en Salud-Secretaria Federal de Salud. At: <http://sinais.salud.gob/medicinaprivada>. Accessed 10 September 2010

- G Olaiz, J Rivera, T Shamah. Encuesta Nacional de Nutrición y Salud, 2006. 2006; Instituto Nacional de Salud Publica: Cuernavaca.

- Instituto Nacional de Geografía y Estadística. Registros administrativos; Estadísticas vitales; Estadísticas de natalidad; Nacimientos registrados por municipio de ocurrencia según lugar donde se atendió el parto. At: <www.inegi.org.mx/lib/olap/general_ver4/MDXQueryDatos.asp>. Accessed September 10, 2010

- Norma Oficial Mexicana NOM-040-SSA2-2004, En materia de información en salud. Diario Oficial de la Federación. DCXXIV, 19, 2005.

- Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía. Conteo de Población 2005. Tabulados Básicos. At: <www.inegi.org.mx/TabuladosBasicos/Default.aspx?.c=10398&s=est>. Accessed 10 September 2010

- J Frenk, J Sepulveda, O Gómez-Dantes. Evidence based health policy: three generations of reform in Mexico. Lancet. 362: 2003; 1667–1671.

- Human Rights Watch. Mexico. Victimas por partida doble. Obstrucciones al aborto legal por violación en Mexico. HRW. 18: 2006; 1(B).

- D Lara, S García, O Ortiz. Challenges accessing legal abortion after rape in Mexico City. Gaceta Médica de Mexico. 142(Suppl 2): 2006; 85–89.

- A Langer, C Garcia-Barrios, A Heimburger. Improving post-abortion care in a hospital in Oaxaca, Mexico. Reproductive Health Matters. 5(9): 1997; 20–28.

- R Jewkes, T Gumede, M Westaway. Why are women still aborting outside designated facilities in metropolitan South Africa?. BJOG. 112: 2005; 1236–1242.

- Grupo de Informacion en Reproducción Elegida. El aborto en los códigos penales de la entidades federativas. 2010; GIRE: Mexico DFAt: <www.gire.org.mx/contenido.php?informacion=31>. Accessed 13 September 2010

- Secretaría de Salud del DF. Statistical information on women performing legal abortions in Mexico City, 2010. (Unpublished data).

- F Juarez, S Singh, S Garcia. Estimates of induced abortion in Mexico: what's changed between 1990 and 2006?. International Family Planning Perspectives. 34(4): 2008; 158–168.

- M Berer. Making abortions safe: a matter of good public health policy and practice. Reproductive Health Matters. 10(19): 2002; 31–44.

- ME Collado, R Alva, L Villa. Embarazo no deseado y aborto en adolescentes: un reto y una responsabilidad colectiva. Género y Salud en Cifras. 6(2): 2008; 17–30.

- M Lafaurie, D Grossman, E Troncoso. Women's perspective on medical abortion in Mexico, Colombia, Ecuador and Peru: a qualitative study. Reproductive Health Matters. 13(26): 2005; 75–83.

- Becker D, Diaz C, Juarez C, et al. Women's perceptions of the quality of public sector abortion services in Mexico City, Presented at: Population Association of America 2010 Annual Meeting, 17 April 2010.

- E Puentes-Rosas, O Gómez-Dantés. Unidades privadas con servicios de hospitalización. Síntesis Ejecutiva. Subsecretaría de Innovación y Calidad, Dirección General de Evaluación del Desempeño, México 2001. At: <www.salud.gob.mx/unidades/evaluacion/publicaciones/sintesis/unidades_privadas.pdf>. Accessed 13 September 2010