Abstract

Abstract

Recent media coverage and case reports have highlighted women's attempts to end their pregnancies by self-inducing abortions in the United States. This study explored women's motivations for attempting self-induction of abortion. We surveyed women in clinic waiting rooms in Boston, San Francisco, New York, and a city in Texas to identify women who had attempted self-induction. We conducted 30 in-depth interviews and inductively analyzed the data. Median age at time of self-induction attempt was 19 years. Between 1979 and 2008, the women used a variety of methods, including medications, malta beverage, herbs, physical manipulation and, increasingly, misoprostol. Reasons to self-induce included a desire to avoid abortion clinics, obstacles to accessing clinical services, especially due to young age and financial barriers, and a preference for self-induction. The methods used were generally readily accessible but mostly ineffective and occasionally unsafe. Of the 23 with confirmed pregnancies, three reported a successful abortion not requiring clinical care. Only one reported medical complications in the United States. Most would not self-induce again and recommended clinic-based services. Efforts should be made to inform women about and improve access to clinic-based abortion services, particularly for medical abortion, which may appeal to women who are drawn to self-induction because it is natural, non-invasive and private.

Résumé

Aux États-Unis, les tentatives de femmes d'interrompre elles-mêmes leur grossesse ont récemment fait l'objet d'une couverture médiatique et de rapports. Cette étude a exploré les raisons incitant les femmes à s'auto-avorter. Nous avons enquêté dans les salles d'attente de dispensaires à Boston, San Francisco, New York et une ville du Texas pour identifier les femmes qui avaient tenté d'auto-avorter. Nous avons mené 30 entretiens approfondis et analysé les données par induction. L'âge médian au moment de la tentative d'auto-avortement était de 19 ans. Entre 1979 et 2008, les femmes ont utilisé diverses méthodes, notamment des médications, des boissons maltées, des plantes, des manipulations physiques et, de plus en plus, du misoprostol. Parmi les raisons de l'auto-avortement figuraient le désir des femmes d'éviter les centres d'avortement, les difficultés d'accès aux services cliniques, particulièrement en raison de leur jeunesse et du manque de moyens financiers, et une préférence pour l'auto-avortement. Les méthodes utilisées étaient généralement aisément disponibles, mais pour la plupart inefficaces et occasionnellement dangereuses. Des 23 femmes avec une grossesse confirmée, trois ont fait état d'un avortement réussi n'ayant pas nécessité de soins cliniques. Une femme a rapporté des complications médicales aux États-Unis. La plupart d'entre elles ne recommenceraient pas à s'auto-avorter et recommandaient des services institutionnels. Il faut informer les femmes sur les services d'avortement dans des centres et en élargir l'accès, en particulier pour l'avortement médicamenteux qui peut convenir aux femmes attirées par l'auto-avortement parce que c'est une méthode naturelle, non invasive et qui respecte l'intimité.

Resumen

En recientes reportajes e informes de casos se han destacado los intentos de interrupción del embarazo mediante la autoinducción del aborto en Estados Unidos. Este estudio exploró las motivaciones de las mujeres para intentar la autoinducción del aborto. Encuestamos mujeres en las salas de espera de clínicas en Boston, San Francisco, Nueva York y una ciudad en Texas para identificar a las que habían intentado la autoinducción. Realizamos 30 entrevistas a profundidad y analizamos los datos de manera inductiva. La edad mediana en el momento del intento de autoinducción fue de 19 años. Entre 1979 y 2008, las mujeres utilizaron una variedad de métodos, como medicamentos, malta, hierbas, manipulación física y, cada vez más, misoprostol. Los motivos para autoinducirse un aborto eran: el deseo de evitar las clínicas de aborto, obstáculos al acceso a los servicios clínicos, especialmente debido a la temprana edad y a las barreras financieras, y la preferencia por la autoinducción. Los métodos utilizados generalmente eran fáciles de obtener pero la mayoría ineficaces y a veces inseguros. De las 23 con embarazos confirmados, tres dijeron que lograron abortar sin necesitar atención médica. Solo una relató haber presentado complicaciones médicas en Estados Unidos. La mayoría no volvería a autoinducirse un aborto y recomendó servicios clínicos. Se deberían realizar esfuerzos por informar a las mujeres acerca de los servicios de aborto en las clínicas y por mejorar el acceso a estos, particularmente al aborto con medicamentos, una opción que probablemente les interese a las mujeres que se inclinan hacia la autoinducción, por ser natural, no invasivo y privado.

In settings where access to safe, legal abortion is restricted, women may attempt to self-induce abortion outside of a clinic setting using a variety of techniques, including inserting objects into the uterus, ingesting harmful substances, exerting external force, or using medications such as misoprostol,Citation1 particularly in Latin America and the Caribbean, where there is widespread availability of the drug.Citation2–4 Self-induction with misoprostol has also been reported in Africa and by African immigrants in Europe.Citation5–7 Studies indicate that misoprostol is safer than other techniques used to self-induce abortion.Citation8

Recent evidence suggests that some women in the United States (US) also attempt to self-induce abortion. Two clinical case reports documented a woman in Massachusetts who used misoprostolCitation9 and another in Washington who inserted a metal coat hanger into her uterus and presented with sepsis.Citation10 There have also been reports in the media of women using various self-induction methods.Citation11Citation12 Yet the assumption has been that women would no longer be driven to self-induce after abortion was legalized in the US in 1973, when complications from unsafe abortion decreased.Citation13

A recent national survey of US abortion patients found that 1.2% reported ever using misoprostol, and 1.4% reported using other substances to self-induce an abortion.Citation14 In another study, among mostly Dominican women in New York City obstetrics and gynecology (ob/gyn) clinics, 37% knew about misoprostol and 5% had used it themselves, although the study did not specify whether the women had done so in the US.Citation15

The purpose of this qualitative study was to explore experiences of abortion self-induction by women living in the US, to better understand women's motivations and suggest practice and policy recommendations to improve access to safe abortion care.

Methods

Participants were recruited as part of a larger study examining knowledge and experience with abortion among women in San Francisco, Boston, New York City and a city in Texas adjacent to the US-Mexico border. The sites were selected to oversample Latinas and low-income women, since prior reports have documented self-induction with misoprostol among these populations in the US.Citation11Citation15 We received ethical approval from all relevant institutional review boards.

Between June 2008 and February 2009, we recruited a convenience sample of 1,425 women aged 15–45 speaking English or Spanish at primary care or ob/gyn clinics (and an abortion clinic in Texas) to participate in a survey (in Texas, the minimum age was 18). In the survey, the women were asked if they had ever attempted to self-induce an abortion, and if so, were invited to participate in an in-depth interview on their most recent experience.

The number of survey participants was: San Francisco (448); Boston (402); New York City (412); Texas (163). Fifty-six women who completed the survey (4.6% of those who had ever been pregnant) reported attempted self-induction, and 29 agreed to participate in an interview. We also did one pilot interview with a woman from one of the San Francisco clinics. We did not ask women why they did not want to do an interview, but many cited time constraints or logistics, while two were not willing and at least two were inadvertently not invited.

Because only minimal changes were made in the interview guide after piloting, we included the pilot interview in the analysis, for a total of 30 interviews (2 from San Francisco, 14 from Boston, 9 from New York, and 5 from Texas). Trained bilingual interviewers conducted interviews in English or Spanish in private areas of the clinics. Questions focused on motivations for self-induction, description of the attempt, and reflections on advantages and disadvantages of self-induction compared with clinic abortion. Interviews were recorded and transcribed. Four participants declined to be recorded, and the interviewer took detailed notes; quotes are not reported for the unrecorded interviews. Interviews lasted an average of 44 minutes. Participants were given US$25.

The interviews were semi-structured, and designed and implemented according to grounded theory.Citation16 Data were analyzed inductively using ATLAS.ti 5.5 for identification of emerging themes. We aimed to identify recurring patterns and outliers of the varying situations in which women attempted self-induction. Six investigators reviewed transcripts and interviewer notes and participated in the coding. Each initial coding was reviewed by another investigator to ensure reliability. Analysis was in the original language of the interview; Spanish quotes were translated into English.

Findings

Participants

At the time of their last self-induction attempt, three participants were living in countries where abortion was legally restricted: Uganda, Nigeria and the Dominican Republic. Two women were living in Puerto Rico, where they incorrectly believed abortion was illegal. We felt it was important to include them in our analysis as their perceptions and beliefs at the time of self-induction may still be current.

Methods of self-induction

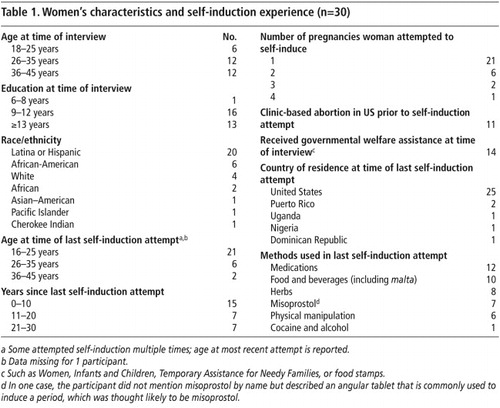

Table 1 provides information about the women, their self-induction experiences and the methods they used. We grouped the methods into six categories; 13 of the women used multiple methods from different categories. The most commonly reported methods were medications (n=12), including vitamin C, aspirin, laxatives, oral contraceptives, hormonal injections, and unspecified pills or injections (but not misoprostol). Among those who used hormonal medications to self-induce, several believed that high doses of contraceptives could cause a miscarriage.

“The pills was my idea… if you get pregnant on birth control, they say to stop, ‘cause it can cause miscarriages.” (Boston 1, age 16)Footnote*

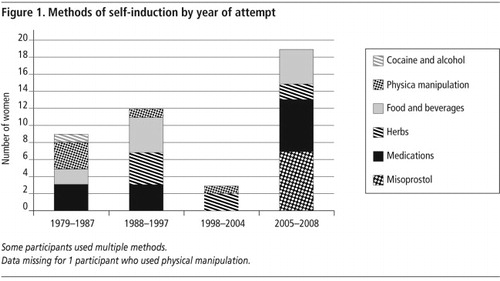

Despite previous reports, less than one quarter of the women reported using misoprostol (n=7). Though our convenience sample makes it difficult to draw any strong conclusions about differences in method use across the country or over time, it is notable that misoprostol was more common among recent cases (see ) and in Texas. All seven women who used misoprostol were living in the US at the time: four in Texas and one each in the three other cities. The women reported obtaining misoprostol from friends and shops, or (in Texas) across the border in Mexican pharmacies. Of the three women who obtained misoprostol directly from a vendor, only one received limited information about its use; none described using a regimen likely to be effective.Citation17

Ten women reported using a food or beverage, including coffee with lemon, warm Coca-Cola with baking soda, unspecified syrups, and malta, a non-alcoholic malted beverage from the Caribbean. Malta was the most commonly used method of self-induction overall (n=8), and all those who reported using it were living in New York or Boston and were aged 19 years or less at the time. They reported using it alone or with aspirin or salt. One woman explained that one had to use a certain Dominican malta that had a label saying pregnant women should avoid it.

“I have no idea how it works. I just know that growing up it was something that was spoken about. Like you would hear people, you know, older family members talking and they would say, [whispering] ‘oh yeah and she took the malta and the aspirin and that's it, there was no more pregnancy.’” (New York 1, age 17)

Six women used physical manipulation, including abdominal trauma, intravaginal trauma, and excessive exercise. Of the two women who reported using intravaginal methods, one attempt occurred in Uganda; the other was in the US around 1983. In general, methods involving abdominal or intravaginal manipulation were attempted more frequently in the more distant past (see ).

Finally, one woman reported using cocaine and alcohol to attempt self-induction.

The women reported learning about methods from friends and family most commonly, sometimes from those living in another country or who had stronger links to practices in that country.

Experience of self-induction

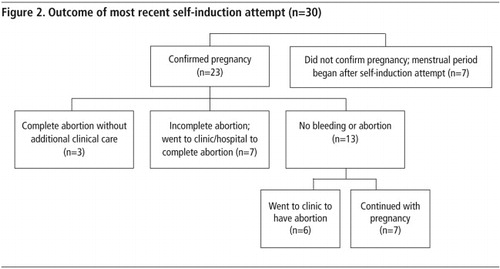

The methods the women used were generally ineffective and caused only mild symptoms like cramping or diarrhoea. Seven never confirmed their pregnancies with a test or clinic visit but believed they were pregnant and said their periods returned after self-induction (). Of the 23 women whose pregnancies were confirmed, only three reported a complete abortion not requiring further attention. One was from Texas and took misoprostol daily for 45 days starting at 6 weeks' gestation. Two others who reported successful abortions used unspecified herbs or malta.

Seven of the remaining 20 women with confirmed pregnancies reported bleeding – five in the US after using misoprostol, one in Puerto Rico after a hormonal injection and one in Uganda after inserting a pen and matchstick into her vagina. Four of these seven women had light bleeding for several days and subsequently had procedures to complete the abortion. The other three, including both of the cases that occurred outside of the US and one of the US misoprostol cases, reported heavy bleeding that required treatment in a hospital, where a D&C was performed, and in one case a blood transfusion was required. Two of these three women with more serious complications said they were in the second trimester of pregnancy.

The remaining 13 women with confirmed pregnancies whose self-induction attempts were unsuccessful experienced only mild symptoms. Six subsequently attended a clinic for abortion, though it took two of these women several weeks before they realized their attempts had been unsuccessful. Such delay, if it means a second trimester abortion, could make the procedure more expensive and more difficult to access.Citation18

Seven women whose attempts were unsuccessful decided to continue the pregnancy. Two were living in countries where abortion was legally restricted, and had limited options or were concerned about health risks. Several who were living in the US realized they were unsuccessful only one or more months later, by which time they felt they were too far along to have an abortion. No woman who took misoprostol decided to continue her pregnancy.

Motivations for self-induction

The women overwhelmingly described negative and desperate emotions upon learning or suspecting they were pregnant and most described knowing immediately that they did not want to continue the pregnancy; only one described being conflicted about her decision. They reported a variety of, and sometimes multiple, reasons to attempt self-induction. Some of these motivating factors pushed women away from clinics, while others drew them toward self-induction.

Desire to avoid clinic abortion

The majority of participants wanted to avoid a clinic abortion. Although most who had a prior clinic abortion did not emphasize negative aspects of the experience, a few did cite this as a reason for avoiding clinics.

“I don't want to deal again – and the questioning and to test me for STDs… and it's this big, long process… I don't want to have to go through that [again] if I don't have to.” (San Francisco 1, age 21)

“A lot of things. It could be a lack of information. And another thing is that I was scared… to actually go to a doctor and maybe they'll do worse than what, you know, I was going to do. I said, a malta is nothing, you know.” (New York 2, age 18)

Barriers to accessing clinic abortion

While some chose to avoid clinics, other women described difficulties accessing abortion care before they attempted self-induction. Half reported that being young at the time was an important factor; either they were unfamiliar with clinics they could go to or they wanted to avoid involving parents. These findings are consistent with several other reports of self-induction in the US among adolescents.Citation9,11,19 Several young women thought they needed parental consent for abortion, although some lived in states where this was not required. One woman knew about the option of a court order to bypass the parental consent requirement, but still preferred self-induction:

“I didn't wanted my mom to know. I didn't want to go to court ‘cause it was gonna be too long and probably he was gonna say no, so I just [said], you know, ‘skip all that, I'm gonna do it. Myself.’” (Boston 2, age 16)

A third of women described financial barriers as a motivating factor. This is not surprising given that the average cost of a non-hospital, first trimester abortion in the US in 2005 was US$413.Citation18 Only 17 states pay for abortion services for Medicaid patients (the national health care plan for low-income individuals), while four states restrict coverage of abortion by private insurance plans.Citation20 Some women said they went to a clinic and were discouraged when they were told the price, while others never went because they believed it was too expensive. A few were concerned their insurance would not cover abortion or that a parent would find out if they used their insurance. The participant who haemorrhaged, requiring a D&C and blood transfusion, lived in Texas where Medicaid does not pay for abortion. Cost was a factor that prevented her from using the clinic. She had used misoprostol and an injection at 13 weeks' gestation. When asked if she would do the same again if she could go back in time, she said:

“If I knew all this would happen, I probably still would do it, because I would have had no choice but to do it, because I didn't have the money… But, if I had the money? Well, of course, I would go probably to a regular clinic or something. But, if I was put in the same exact situation all over again? I'd probably do it again.” (Texas 1, age 30)

Several women who eventually had a clinic abortion were surprised to find out how accessible services were. One went to her doctor about a week after taking pills from Puerto Rico and malta that had no effect:

“Did I think that maybe they did it there? No. I didn't know. I was shocked, actually, when they told me that they could do it there. ‘Cause I always thought you had to go to a special abortion clinic.” (Boston 3, age 19)

Preference for self-induction

A number of women also reported a preference for self-induction. A third mentioned that self-induction was not the same as clinic abortion, and many compared self-induction to menstrual regulation, inducing a period, or emergency contraception.

“You can do it fairly quickly… and you just… get your period, and you don't even associate it with a possible pregnancy… There's Plan B [emergency contraception]. I used that just when a condom broke… That was essentially the same thing.” (San Francisco 1, age 21)

“It's not a baby already. It's just blood. So I don't feel like it's killing a baby, because it's just developing.” (Boston 4, age 22)

“When I was growing up I was against abortion… You know the whole Catholic.. you know it's wrong. You get pregnant then you keep it and that's it. But I never really thought of the whole malta and aspirin thing as inducing your own abortion…” (New York 1, age 17)

A few women chose to self-induce because it was more private than a clinic abortion, and even more considered it more private looking back on their experience. The benefits they described included being able to hide it from others and to have a less medicalized procedure.

“In a clinic, it's more – clinical, you know… You have people walking back and forth, you have people opening up the doors when you're in there and there's just no privacy, it's more hard… harsh… As opposed to being at home, you're in your own environment, you're surrounded by things that make you feel safe and make you feel comfortable.” (Boston 5, age 20)

Reflections on self-induction

Twenty-four women indicated they would not attempt self-induction again in the future, and many said this because the method they had used was ineffective, unsafe, or could cause complications. These women had used a range of methods; only one of them had experienced serious complications. Others reflected that they were young when they attempted self-induction, and being older or in a different place in their lives, they would not do it again.

Most women mentioned the potential risks to their own reproductive system, or to the fetus if the pregnancy continued, as a disadvantage of self-induction. For two, fear of having harmed the fetus motivated them to seek a clinic abortion after an unsuccessful attempted self-induction.

Many described uncertainty while self-inducing, not knowing how to use the method properly or what to expect would happen, what to do in case of a problem, and whether it was successful – all as disadvantages.

“When you're doing it yourself, you don't know what you're doing. So, you could be killing yourself.” (Boston 6, age 26)

Discussion

Only 4.6% of ever-pregnant women participating in our survey reported a history of attempting self-induction, and several of these cases occurred outside the US. Our study did not measure the prevalence of abortion self-induction, but these findings are consistent with a recent survey that found that less than 3% of abortion patients reported attempting self-induction, suggesting that this phenomenon is uncommon in the US.Citation14

Medical complications were rare in this sample, although another recent case report of a woman using intravaginal trauma highlights that major complications still occur with unsafe abortion in the US.Citation10 Women may also face legal prosecution for self-inducing their abortion, which has occurred in several cases.Citation11Citation21

The media have focused on Latinas self-inducing abortion in the US.Citation11,21,22 In the national survey of abortion patients, being foreign-born, but not race or ethnicity, was significantly associated with a history of ever attempting self-induction.Citation14 While self-medication with pain medicine, antibiotics and other drugs obtained at pharmacies without a prescription for a variety of conditions has been documented in several countries in Latin America,Citation23 this may be more related to barriers to access or concerns about quality of care than any “cultural” preference. A third of the women that we interviewed did not identify as Hispanic or Latina.

Despite facing barriers to clinical services and often failing in their self-induction attempts, women in this study were generally resolute to end the pregnancy. Although many tried easily accessible methods unlikely to terminate a pregnancy, this did not usually reflect ambivalence about abortion. Two-thirds of participants with a failed self-induction attempt went for a clinical abortion, and many of those who continued with their pregnancies did so because they felt they had no other option.

Our study has several limitations. Women were recruited from clinic settings and therefore had knowledge of and access to clinic-based health services. The study was also conducted in three states where Medicaid covers abortion (but not Texas). Gaps in knowledge and barriers to abortion services highlighted here may be more acute for women with even less access to health care. Additionally, while the women mostly said they would not attempt self-induction again, it is important to remember that most of their self-induction attempts were not successful. This might have been different had more of them successfully terminated their pregnancies. Finally, the extent to which our findings are reflective of the experiences of women more generally in the US is uncertain, given our small sample size and convenience sampling. Despite these limitations, this research provides important insights into the practice of abortion self-induction in the US.

The factors that pushed women away from clinics demonstrate the negative impacts of policies such as parental notification and lack of insurance coverage for abortion, and the problems faced by women, especially young women, who are not well informed about these policies. The impact of limitations on public funding for abortion may only worsen with the recent passage of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (2010), which aimed to reform the inequitable US health care system. While 94% of the 12.4 million uninsured women in the US are likely to qualify for Medicaid or federal subsidies when the health care overhaul is fully implemented, women will still be unable to use Medicaid for elective abortions, except those who live in the 17 states that provide abortion coverage from state contributions.Citation24 Additionally, states will be able to ban abortion coverage in federally-subsidized private insurance plans. Undocumented immigrants will continue to have problems, as they will not be eligible for Medicaid in most states.Citation25

Our findings point to the need for provider education about the laws and policies that govern abortion access, and the importance of informing women about services, including funding sources. Many women learned about the methods they used from family and friends, suggesting that broader social networks need to be targeted to disseminate information about safe abortion care, while at the same time addressing issues of stigma.

Some women chose to self-induce for many of the same reasons that some prefer medical abortion over a surgical procedure: because it is non-invasive, natural, easy and private.Citation26 Most women in our study equated a clinic abortion with a surgical procedure and did not mention the option of obtaining mifepristone+misoprostol abortion at the clinic. Clinic-based medical abortion might be an acceptable alternative to women considering self-induction, especially as standard practice now includes taking misoprostol at home.Citation27 A recent study among low-income, Spanish-speaking women in New York found that medical abortion was highly acceptable.Citation28 Primary care clinicians, including paediatricians, should inform their patients about the option of medical abortion and ideally offer the pills on-site to make it as accessible as possible.

Given that some women prefer a less medicalized abortion experience, is there a way that medical abortion could be made even simpler to offer and more acceptable to women? The evidence suggests that ultrasound is not required to determine gestational ageCitation29 or to confirm completion of abortion,Citation30 and research is underway on the acceptability of home use of mifepristone as well as misoprostol. Mid-level clinicians can safely provide the method with physician back-up as needed.Citation31 Putting this evidence into practice, while addressing the issue of cost, removing unnecessary legal restrictions, and informing women about the option of medical abortion, would better meet women's needs, improve access, and perhaps make self-induction with ineffective and unsafe methods even less necessary in the US context.

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by grants from the Society of Family Planning, Wallace A Gerbode Foundation, David and Lucille Packard Foundation, Mary Wohlford Foundation, and an anonymous donor. A version of the paper was presented at the annual meetings of the American Public Health Association, 9 November 2009, and the Society for Applied Anthropology, 24 March 2010. We would like to thank Signy Judd and Liza Fuentes, who helped design and carry out the study, as well as our interviewers: Alma Avila Pilchman, Monti Castañeda, Cecilia Marquez, Erica Seppala, Silvia Patricia Solis, and Margarita Velasco. We also thank Christine Dehlendorf, Nilda Moreno, and Lynn Borgatta, and the clinic staff who helped coordinate the study at each site.

Notes

* Ages noted are at the time of self-induction.

References

- World Health Organization. Unsafe abortion: Global and regional estimates of the incidence of unsafe abortion and associated mortality in 2003. 2007; WHO: Geneva.

- RM Barbosa, M Arilha. The Brazilian experience with Cytotec. Studies in Family Planning. 24(4): 1993; 236–240.

- H Espinoza, K Abuabara, C Ellertson. Physicians' knowledge and opinions about medication abortion in four Latin American and Caribbean region countries. Contraception. 70(2): 2004; 127–133.

- MM Lafaurie, D Grossman, E Troncoso. Women's perspectives on medical abortion in Mexico, Colombia, Ecuador and Peru: a qualitative study. Reproductive Health Matters. 13(26): 2005; 75–83.

- MM Jones, K Fraser. Misoprostol and attempted self-induction of abortion. Journal of Royal Society of Medicine. 91: 1998; 204–208.

- RF Hess. Women's stories of abortion in southern Gabon, Africa. Journal of Transcultural Nursing. 18(1): 2007; 41–48.

- M Escumalha, C Gouveia, M Cunha. Neonatal morbidity and outcome of live born premature babies after attempted illegal abortion with misoprostol. Pediatric Nursing. 31(3): 2005; 228–231.

- A Faúndes, LC Santos, M Carvalho. Post-abortion complications after interruption of pregnancy with misoprostol. Advances in Contraception. 12(1): 1996; 1–9.

- MS Coles, LP Koenigs. Self-induced medical abortion in an adolescent. Journal of Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology. 20(2): 2007; 93–95.

- TA Saultes, D Devita, JD Heiner. The back alley revisited: sepsis after attempted self-induced abortion. Western Journal of Emergency Medicine. 10(4): 2009; 278–280.

- BR Ballou, A Ryan. DA: Young mother botched abortion with ulcer medication. Boston Globe. 24 January 2007. At: <www.boston.com/news/globe/city_region/breaking_news/2007/01/da_young_mother_1.html>. Accessed 16 March 2010

- P Ramirez III. Self abortion: woman took Tylenol, Motrin. Post Standard Daily Newspaper. 26 July 2007. At: <http://blog.syracuse.com/news/2007/04/west_monroe_woman_charged_with.html>. Accessed 27 September 2010

- W Cates. Legal abortion: the public health record. Science. 215(4540): 1982; 1586–1590.

- RK Jones. How commonly do US abortion patients report attempts to self-induce?. American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2010[Epub ahead of print]

- MA Rosing, CD Archbald. The knowledge, acceptability, and use of misoprostol for self-induced medical abortion in an urban US population. Journal of American Medical Women's Association. 55(3 Suppl): 2000; 183–185.

- K Charmaz. Constructing grounded theory: a practical guide through qualitative analysis. 2006; Thousand Oaks CA: Sage.

- H von Hertzen, G Piaggio, NT Huong. WHO Research Group on Postovulatory Methods of Fertility Regulation. Efficacy of two intervals and two routes of administration of misoprostol for termination of early pregnancy: a randomised controlled equivalence trial. Lancet. 369(9577): 2007; 1938–1946.

- RK Jones, MR Zolna, SK Henshaw. Abortion in the United States: incidence and access to services, 2005. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 40(1): 2008; 6–16.

- B Honigman, G Davila, J Petersen. Reemergence of self-induced abortions. Journal of Emergency Medicine. 11(1): 1993; 105–112.

- Guttmacher Institute. An overview of abortion laws, State Policies in Brief. Available at: <www.guttmacher.org/statecenter/spibs/spib_OAL.pdf>. Accessed 16 March 2010

- S Yanow. The best defense is a good offense: misoprostol, abortion, and the law: Conference summary and strategic recommendations; 28–29 August 2009; New York City. Gynuity Health Projects; Reproductive Health Technologies Project. August. 2009. At: <http://gynuity.org/downloads/Misoprostol_Abortion_and_Law.pdf>. Accessed 28 September 2010

- JB Lee, C Buckley. For privacy's sake, taking risks to end pregnancy. New York Times. At: <www.nytimes.com/2009/01/05/nyregion/05abortion.html>. Accessed 28 September 2010

- JM Castel, JR Laporte, V Reggi. Multicenter study on self-medication and self-prescription in six Latin American countries. Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 61(4): 1997; 488–493.

- Kaiser Family Foundation. Health reform: implications for women's access to coverage and care. 2009. At: <www.kff.org/womenshealth/upload/7987.pdf>. Accessed 30 July 2010

- Raising Women's Voices. Fact sheet: health reform and reproductive health: positive and negative effects. March 2010. At: <www.raisingwomensvoices.net/storage/RWV%20on%20Health%20Reform%20and%20Reproductive%20HealthFINAL3.30.10.pdf>. Accessed 20 July 2010

- B Winikoff, C Ellertson, B Elul. Acceptability and feasibility of early pregnancy termination by mifepristone-misoprostol. Results of a large multicenter trial in the United States. Mifepristone Clinical Trials Group. Archives of Family Medicine. 7(4): 1998; 360–366.

- W Clark, M Gold, D Grossman. Can mifepristone medical abortion be simplified? A review of the evidence and questions for future research. Contraception. 75: 2007; 245–250.

- SB Teal, T Harken, S Jeanelle. Efficacy, acceptability and safety of medication abortion in low-income, urban Latina women. Contraception. 80: 2009; 479–483.

- K Blanchard, D Cooper, K Dickson. A comparison of women's, providers' and ultrasound assessments of pregnancy duration among termination of pregnancy clients in South Africa. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 114(5): 2007; 569–575.

- W Clark, H Bracken, J Tanenhaus. Alternatives to a routine follow-up visit for early medical abortion. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 115(2 Pt 1): 2010; 264–272.

- J Yarnall, Y Swica, B Winikoff. Non-physician clinicians can safely provide first trimester medical abortion. Reproductive Health Matters. 17(33): 2009; 61–69.