Abstract

This paper is about the economic consequences of the stigmatisation and illegality of abortion and its almost complete removal from public health services in Poland since the late 1980s. Once abortion left the public sphere, it entered the grey zone of private arrangements, in which a woman's private worries became someone else's private gain, and her sin turned into gold. The most important consequence was social inequality, as the right to health, life, information and safety became commodities on the free market. Women with money, who are more likely to have political influence, find this bearable, while working class women lack the political capital to protest. In the private sector, there are no government controls on price, quality of care or accountability, and almost no prosecutions. With an estimated 150,000 abortions per year, a rough estimate of US$ 95 million is being generated annually for doctors, unregistered and tax-free. Thus, the combined forces of right-wing ideology and neoliberal economic reforms have created reproductive and social injustice. To address this, stigmatisation of abortion must be countered. But a change in the political climate, a less restrictive interpretation of the law, or even a new law would not resolve the problem. Given reductions in public health care spending, abortion would remain excluded from state coverage unless neoliberal health care reforms could be reversed.

Résumé

Cet article décrit les conséquences économiques de la stigmatisation et de l'illégalité de l'avortement, et de son retrait presque complet des services de santé publique en Pologne depuis la fin des années 80. Après avoir quitté la sphère publique, l'avortement est entré dans la zone grise des arrangements privés, où les problèmes privés d'une femme se transforment en revenus privés pour ceux qui s'enrichissent avec son péché. La principale conséquence est l'inégalité sociale, puisque le droit à la santé, à la vie, à l'information et à la sécurité est devenu un bien en vente sur le marché libre. Les femmes fortunées, qui ont plus de probabilités d'être politiquement influentes, trouvent cela supportable, alors que les femmes des classes laborieuses manquent du capital politique requis pour protester. Dans le secteur privé, il n'y a pas de contrôles gouvernementaux sur le prix, la qualité des soins ou la responsabilité, et presque pas de poursuites. On estime que quelque 150 000 avortements par an génèrent pour les médecins environ 95 millions de dollars chaque année, non déclarés et nets d'impôts. Les forces combinées de l'idéologie de droite et des réformes économiques néolibérales ont donc créé une injustice sociale et génésique. Pour la corriger, il faut contrer la stigmatisation de l'avortement. Mais un changement du climat politique, une interprétation moins restrictive de la loi, ou même une nouvelle loi ne résoudrait pas le problème. Avec les réductions des dépenses de santé publique, l'avortement demeurerait exclu de la couverture étatique à moins d'un reversement des réformes néolibérales de la santé.

Resumen

Este artículo trata sobre las consecuencias económicas de la estigmatización e ilegalidad del aborto y su omisión casi total de los servicios de salud pública en Polonia desde finales de la década de los ochenta. Una vez suspendidos los servicios de aborto en el sector público, estos entraron en la zona gris de arreglos privados, en la cual las inquietudes personales de una mujer reditúan ganancias para profesionales particulares y su pecado se convierte en oro. La consecuencia más importante fue la desigualdad social, a medida que los derechos a la salud, vida, información y seguridad pasaron a ser insumos en el mercado libre. Para las mujeres adineradas, quienes tienden a tener más influencia política, esto es tolerable, mientras que las mujeres de la clase obrera carecen de capital político para protestar. En el sector privado, el gobierno no controla los precios, la calidad de la atención o la responsabilidad de los servicios y casi no hay enjuiciamientos. De unos 150,000 abortos anuales, los médicos generan aproximadamente US$ 95 millones al año, no registrados y libres de impuestos. Por consiguiente, las fuerzas combinadas de ideología derechista y reformas económicas neoliberales han creado injusticia reproductiva y social. Para eliminar esta injusticia es necesario contrarrestar la estigmatización en torno al aborto, pero no se puede resolver el problema con tan solo un cambio en el clima político, una interpretación menos restrictiva de la ley o incluso una nueva ley. En vista de las reducciones en los gastos relacionados con la salud pública, los servicios de aborto continuarán siendo excluidos de la cobertura estatal a menos que se revoquen las reformas de salud neoliberales.

On 10 March 2010 I was a guest on a morning TV show on a national Polish TV channel, to represent a pro-choice/reproductive justice point of view in a discussion about a do-it-yourself abortion poster that had been displayed on bus stops in łódź a few days earlier. The poster, playing on Mastercard advertisements, pictured a woman in underwear, with the words:

“Airplane ticket to Great Britain – 300 PLN. Accommodation – 240 PLN. Abortion pills in a public clinic – 0 PLN. Relief after a procedure carried out in respectable conditions – priceless. For everything else you pay less than you would to use the Polish underground.”

The TV host suggested that many people consider it outrageous to talk about abortion in the context of prices and travel arrangements. It seemed in his view that the appropriate take on abortion was as a deep moral problem, a dilemma, and probably a traumatising experience. He therefore insisted on an emotional, rather than economic, definition of the “problem of abortion”. The poster struck him as simplistic, inappropriate and disrespectful, as it suggested Polish women were more occupied with the practical, rather than the philosophical, aspect of pregnancy termination.

Our mutual astonishment at these differences reflects the disparity between the dominant discourse on abortion and the way reproductive health NGOs and the feminist movement have been describing abortion. The media, the Catholic church and politicians concentrate on the moral and political aspects of the matter, asserting a constitutional right to life of a fetus, and about Christian values, which Poland needs to convince decadent Europe to acceptCitation2. At the same time, Polish NGOs concerned with reproductive health, such as the Federacja na Rzecz Kobiet i Planowania Rodziny (Federation for Women and Family Planning), and the women's movement are mainly trying to draw attention to the medical and economic consequences that the abortion law has for women, and that unequal access to abortion results in reproductive and social injustice.Footnote*

The public sphere in Poland is dominated by the world view represented by right-wing politicians and the leaders of the Catholic church, who condemn abortion and women who have had one. The abortion issue is being discussed mainly as a political issue, as a question of conflicting values, as a mirror reflecting the position of the Church in the Polish state, and the influence of religion in politics, and finally, as an issue of women's rights and the collision of international law with the practical consequences of the law. Much less frequently, however, is the prohibition of abortion in Poland discussed in terms of economics, prices, profit and the extent of involvement of the private sector in reproductive health care.

This paper is about the relationship between the stigmatisation of abortion and the commercialisation of abortion services in Poland. It is based on data from government documents, reports of NGO and international organisations, and published articles. I also cite interviews I did for a report on the situation of women in Poland,Citation4–6 and during fieldwork on abortion for my MA thesis in social anthropology at the University of Warsaw.Citation7

Sin turned into gold

In Poland, private sector health care providers have almost a monopoly on abortion services. Abortion has been criminalised and stigmatised in the public sphere and in public health care facilities in Poland. It has been pronounced to be morally wrong, legally prohibited, made inaccessible in public hospitals, and unacceptable to speak of, even between the closest of friends. Once abortion leaves the public sphere, it enters the grey zone of the private: private arrangements, private health care and – the most private aspect – private worries. In the private sector, illegal abortion must be cautiously arranged and paid for out of pocket. When a woman enters that sphere, her sin turns into gold. Her private worries become somebody else's private gain. And the more abortion is stigmatised in the public sphere, the more women depend on the private sector for solutions.

“In Poland it is common for doctors to deny care to (pregnant) women whose health or life is in danger, because doctors count on them to “cope” with health problems privately. A pregnant woman cannot be sure whether a doctor who issues an opinion about her pregnancy is guided by what is good for her, or by his own apprehension, prejudice or interest. Doctors do not want to perform abortions in public hospitals, they are ready, however, to take that risk when a woman comes to their private practice. We are talking about a vast, untaxed source of income. That is why the medical profession is not interested in changing the abortion law.” (Wanda Nowicka, Executive Director, Federation for Women and Family Planning)Citation4

Stigmatisation was the primary reason why abortion disappeared from public health services and for the emergence of a market for private abortion services. The 1993 abortion law was only a part of that process, and a wider policy of limiting access to legal abortion to the minimum. The law itself is not observed, as even women who qualify for a legal procedure are unlikely to get it. As I will show, stigmatisation of abortion – public discourse on abortion, particular government policies, the way regulations are interpreted by doctors – play as big a role as the actual law.

From public to private: health care reforms in a post-socialist state

During the period of state socialism in Poland, the right to health care was universal. Hospitals and clinics were owned and run centrally by the state. After the 1989 political breakthrough the Polish government initiated privatisation, decentralisation and commercialization of the health care system.Citation8,9 Within the new Polish economic ideology, hospitals became institutions guided mainly by financial concerns and priorities, and ideas of effectiveness, the same as commercial companies. The new political and economic system allowed a boom in growth of the private health sector, that more and more citizens rely on. The logic of the reforms followed a larger trend present in the post-socialist countries, to apply free market rules to hitherto public and state-run sectors.Citation8 Universal health care was subjected to substantial cuts: a number of services and medicines were no longer covered by the state health care system, and had to be paid for by citizens out of pocket.Citation9 Furthermore, cuts in health care resulted in a shortage of medical personnel and long queues for patients. In order to bypass the queue or receive better quality treatment, patients resort to informal payments.Citation9

These changes influenced the availability of all reproductive health services in Poland, including for contraception, antenatal testing and pregnancy care,Citation9 but in the case of abortion it is impossible to comprehend the extent of the commercialisation and privatisation without considering the political context.

During state socialism abortion was legal in Poland for medical, legal and social reasons, under a law passed in 1965.Citation10 In practice, the law was interpreted in a way that allowed the woman to decide if her social conditions allowed her to have a child. Private health care providers existed, but their activities were overshadowed by the state-run public system. Abortion was accessible and, compared to present prices, affordable.

“Nobody asked me why I wanted to terminate my pregnancy… I guess it was pretty affordable, because I remember my boyfriend and I could pay for an abortion privately [not in a public hospital], and we were both students. So even a student could afford it.” (Maria, aged 65, who had two pregnancy terminations before 1989)Citation7

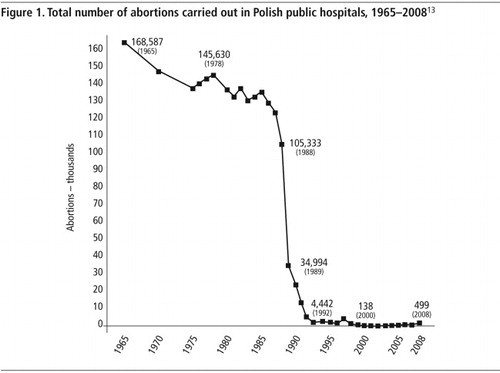

illustrates how the number of legal abortion procedures performed in public hospitals in Poland fell by 99% during the late 1980s and early nineties. Where did all the abortions go? They migrated to private practices in just a few years, thanks to an ideological offensive by the Catholic church, which determined the way the law was interpreted and implemented.

This process happened in three stages. In 1965–88 abortion was legal and accessible. The annual number of abortions was around 130,000 and falling steadily – by 37% in 23 years.

In 1988–93 the number of legal abortions fell rapidly from 105,333 to 685, that is by 99% in only six years. From 1993 to today, the number of legal abortions remains minimal, between 124 and 499 annually. The year 1997 was the exception, the number of legal abortions rose to 3,047 because in 1996 abortion for social reasons was legalized for one year, until the Constitutional Tribunal ruled it unconstitutional.Citation14

The single biggest annual drop in public sector abortions was from 1988 to 1989, by 68%, although the law limiting access to abortion was only passed four years later. What happened? 1989 is the year the democratic opposition gained political victory over the old communist regime, leading to the first free elections, and paving the way for political changes in the whole Soviet bloc. The Polish opposition movement, Solidarność, cooperated closely with the Catholic church. The victory of the opposition brought victory also for the church, which took an active role in shaping the young state's political agenda.

It was in the 1980s that the Polish “pro-life” movement was born.Citation15,16 Women started fleeing from the public sector for abortions when the restrictive bill was actually introduced in the changing political climate after 1989. In 1990 the second congress of Solidarność supported a restrictive abortion bill project. The Women's Committee of Solidarność protested against that decision and was thence liquidated.Citation17 In 1991, a new Medical Ethics Code (Kodeks Etyki Lekarskiej) was passed by the medical profession, obliging providers to make abortion much harder to obtain than the law at that time required.Citation18 There were street demonstrations against penalising abortion.Citation7 In 1992 the Social Committee for a Referendum on the Subject of Penalizing Pregnancy Termination gathered over a million signatures under a petition to put the right to abortion to a national vote. The petition was ignored by the government, and the referendum was never carried out, due to the Church's opposition. Thus, the period 1989–1993 was a time of intensive political battles over abortion.

In the early 1990s a new discourse on abortion became dominant: the words “pregnant woman” were replaced by “mother” and “fetus” replaced by “unborn baby” or simply “life”.Citation19 Politicians elaborated on the fundamental role of an abortion ban for the new Polish state, and the “pro-life” movement helped transform the national consciousness with images of bloody fetuses,Citation15 thanks to developments in science and intra-uterine photography.Citation20 This process was described by Agnieszka Graff as “a lost battle over language”.Citation19 The new language on abortion was incorporated into official state documents and into the law. It was also adapted by some politicians and members of the medical profession, with the emergence of “post-abortion syndrome”.Citation16

The letter of the law allows for legal pregnancy termination for medical and legal reasons. However, it is interpreted in a very restrictive way, even violated by doctors, who seriously limit women's access even to legal abortion. Should anyone forget not to expect a legal abortion in a public facility, there have been terrible cases to remind them. The first was Alicja Tysiąc, a woman who won her case in the European Court of Human Rights in 2007 after gynaecologists refused to perform an abortion despite a serious risk of damage to her sight that the pregnancy presented, breaking Articles 3, 8, 13 and 14 of the European Convention on Human Rights.Citation21 Footnote*

Before her, in 2004, a young pregnant woman who had been denied emergency health care died due to enteritis inflammation. She was told “she should care less about her ass and more about her baby”.Citation23 The doctors were probably too scared to start treatment, because it might have interrupted the pregnancy. In 2008, her mother filed a suit in the European Court of Human Rights, with the help of Federation for Women and Family Planning, which is still in progress.Citation24

In 2008 the case of a 14-year-old called Agata was debated in the Polish media: the girl was entitled to a legal abortion both because of her age and because she had been raped. The case became the centre of national attention. No hospital wanted to perform the procedure, a priest from her parish followed the girl to another city to try to get her to change her mind, newspapers printed articles and letters on the question of whether an abortion should be made available to her, and at some point the girl was even taken away from her parents. After a few weeks, a legal abortion was arranged by the Ministry of Health.Citation25

According to the law, all three of these women had the right to a legal abortion, due to their health, age or having been raped. However, as Agata's mother said:

“The police officer at the police station told me that we are entitled to a legal abortion. I thought I didn't have to send my daughter to a butcher [doctor performing illegal abortions], so I didn't even look at advertisements in the newspaper [for illegal abortion]. Now I get what I deserve.”Citation26

Thus, the letter of the law alone is not the issue as it can be interpreted in many ways. It is the interpretation and the political intent that pushed legal abortions out of public hospitals and more widely, the public sphere. The more abortion was stigmatised in the public sphere, the more women felt they had to rely on private arrangements to solve their problems. There is therefore a direct link between the extent of stigmatisation of a health service like abortion and the amount of space for growth of its provision in the private sector.

The real price of abortion in Poland

The most important consequence of the 1993 abortion law was the social inequality it created. The cost of a surgical abortion (D&C) in 2006 varied from 1,500–2,500 PLN, up to 4,000 PLN (380–500 up to 1,000 EUR) and the cost of medical abortion from 400–1,000 PLN (100–250 EUR).Citation23 In 2009 the average monthly household income was about 1,114 PLN per capita.Citation27 This means the cost of a surgical abortion exceeded the average monthly income of a Polish citizen. But these are only averages. The situation of many women is even harder, especially in rural areas and among teenagers, the unemployed and women supporting children alone (single parent households had an average of 929 PLN of monthly disposable income per capita.Citation27

The abortion pills mifepristone and misoprostol can be accessed also through a non-for-profit project called Women on Web. After the consultation that takes place online, the pills are sent to the woman. A donation of €70 (about 275 PLN) is requested if she can afford it. This option is only available to women with access to the Internet and a certain skill in using it. Cross-border travel for abortion care is also popular, with women travelling mainly to the UK and Germany, where it is legal and safe.

Although abortion procedures are available nearly exclusively from private sector providers, their prices are not regulated. The price is whatever they set. Providers have no incentive to compete with each other through lower prices, because women in need of a procedure are in a desperate situation. There is no public institution that ensures access to abortion to those who cannot afford the fees. Therefore, society is divided into those who can and those who cannot find acceptable ways of getting around the law. The higher the income, the more immune a person is to the restrictions of the law. Members of the middle class can afford to turn to the private sector. The rest, abandoned by the state, are left with few acceptable solutions when in need of an abortion.

This creates a grim prospect for change, as well. “The possession of 2,000 PLN… became the entitlement to moral self-rule,” as Kinga Dunin, Polish feminist thinker, put it bluntly.Citation28 The situation seems to be similar in Ireland, where regulations regarding abortion are even more restrictive, but can be bypassed if one has the means to travel abroad.Citation29 Women from the middle class, who are more likely to have an influence on the political situation, find these conditions bearable, while women from the working class lack the political capital to protest against the discrimination against them. The effort to change the law cannot succeed unless women from all social classes show solidarity.

Meanwhile, in the private sector, a vast new, profitable market in health care emerged, without any government control on price, quality of care or accountability. If the cost of a surgical abortion is on average 2,000 PLN, and an estimated 150,000 procedures are carried out annually, that would make about 300 million PLN of annual income (approximately 95 million USD or 75 million EUR) – unregistered and tax-free.Citation23 These numbers are of course very raw estimates. Neither the real number of procedures, nor the exact cost is known – another result of the private sector being outside government control. Doctors providing abortions privately therefore have little interest in legalising abortion.

Doctors who perform illegal procedures are not discouraged by the law, even though in Poland the sentence for procuring an abortion is up to three years in prison for the provider, not the patient (or up to eight years if it was against the woman's will).Footnote* The government report on the number of cases detected of illegal abortions (with a woman's consent) was, in 2006 for example, only 47 cases,Citation30 however, or 0.03% of the estimated total illegal abortions.

How, then, did cases of unlawful pregnancy termination come to the attention of the police at all? In 2005 there were 100 cases of abortion law violations registered by the public prosecutor's office. In 31 cases, the information resulted from other investigations; 24 came from hospitals; 13 from partners, husbands or ex-husbands of pregnant women; six from the families of pregnant women (four of them from parents); and ten from women themselves. In the other eight cases, the notifications were anonymous: in two cases a member of the public found a dead fetus in the trash; in one case a person was witness to an event connected to an illegal abortion, and in five cases the information resulted from police proceedings following notifications from social workers and unidentified “social organisations”. Following these 100 cases 18 were dismissed without charges, and 82 were brought into preliminary proceedings. Of the 82, 41 cases of unlawful pregnancy termination (or an attempt at such) with the women's consent (which means proceedings against medical providers), 27 cases of helping a pregnant woman terminate a pregnancy or inducing her to do so, six cases of both these violations and eight cases of pregnancy termination without the women's consent (by violence, threats or ruse). In 54 of these cases proceedings were discontinued.Citation31

The reluctance of the state authorities to prosecute, even when advertisements for illegal abortion services can be found in the newspapers, raises this question: is it possible that the purpose of the law is not to reduce the number of abortions, but to serve a purely political role, as a symbolic achievement of the Church and right-wing parties?

Extending privatisation to IVF and other reproductive health services

Abortion is not the only reproductive health care service that is subjected to stigmatisation and commercialisation. Infertility treatment (specifically in vitro fertilisation or IVF) is being treated similarly.Citation6 Infertility treatment is not refunded in the Polish public health care system.Citation9 In 2007, a proposition to include these procedures in publicly-funded health care met fierce political opposition, and throughout 2008 and 2009 IVF became “the new abortion debate”. Politicians on the right used the same language to talk about fertilised eggs in laboratories that they use to talk about fetuses. They claimed to “defend life” and “prevent murder” and proposed two restrictive bills that would seriously limit the use of IVF.Citation32Citation33Citation34 The Catholic church was especially active in the debate, with one of the bishops describing the creation of embryos they are not implanted in IVF as “a sophisticated form of abortion” and comparing IVF to “creating Frankensteins”. Some priests have been accused of discriminating against children who were conceived by IVF and treating them as if they were inferior, even describing them on the radio and in newspapers as “weaker physically and mentally” or “a consumer good”.Citation35 By extending the stigmatisation to IVF, and as Joanna Mishtal has shown also to contraceptive and other reproductive health services as part of the neoliberal changes in the health care system that were implemented in Poland after 1989,Citation13 the Catholic church and right-wing politicians show they are aiming to broaden the field of their symbolic domination of women's reproductive health and rights.

The domination, in fact, monopolisation of abortion services by the private sector causes social inequality because commercialised abortion services are not affordable for everyone. But because stigmatisation of abortion dominates the public discourse, the economic aspects are rarely discussed. Thus, the combined forces of right-wing Catholic ideology and neoliberal economic reforms have resulted in reproductive and social injustice.

To address these elements of the problem, countering the stigmatisation of abortion is a necessary step. But a change for the better in the political climate, a less restrictive interpretation of the law, or even a change in the law at this juncture will not guarantee a solution to the problem of social inequality for women in need of abortion. Given the current tendency to reduce public spending on the public health care system, abortion and other reproductive health services would probably still be excluded from state coverage. Thus, an effective effort to improve the situation for women in Poland would also need to take on board challenging neoliberal health care reforms.

Notes

* Reproductive justice is a concept developed by US feminist organisations of women of colour.Citation3 It links social justice with reproductive health, based on the conviction that “it is important to fight equally for 1) the right to have a child; 2) the right not to have a child; and 3) the right to parent the children we have, as well as to control our birthing options, such as midwifery” and “the necessary enabling conditions to realize these rights”. The term was adopted by some Polish activists, and in 2009 the first Polish Reproductive Justice Days were organised in Warsaw.

* These regulate, respectively, prohibition of inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment, the right to private and family life, and the right to an effective remedy and prohibition of discrimination.Citation22

* Every year the police report a few cases of unlawful pregnancy termination carried out against the woman's will: 4 cases in 2003, 5 in 2004, 4 in 2005, and 2 in 2006.Citation23

References

- Ustawa z dnia 7 stycznia 1993 r. o planowaniu rodziny, ochornie płodu ludzkiego i warunkach dopuszczalności przerywania ciąży (z 1993 r., Dz.U. Nr 17, poz. 78; z 1995 r., Nr 66, poz. 334, z 1996 r., Nr 139, poz. 646, z 1997 r. Nr 141, poz. 943, Nr 157, poz. 1040 i z 1999 r. Nr 5, poz. 32), (1993).

- Janion M. Niesamowita Słowiańszczyzna. Kraków, 2006.

- Understanding Reproductive Justice. 2006; SisterSong Women of Color Reproductive Health Collective: Atlanta.

- A Chełstowska. Oddzielić zdrowie od ideologii. Interview with Wanda Nowicka, chair, Federation for Women and Family Planning. A Czerwińska, J Piotrowska. Raport: 20 lat – 20 zmian Kobiety w Polsce w okresie transformacji 1989–2009. 2009; Fundacja Feminoteka, Heinrich Böll Foundation: Warszawa, 33–35.

- A Chełstowska. Poród po ludzku. Co się zmieniło od 1989 roku w opiece okołoporodowej w Polsce? Interview with Anna Otffinowska, chair, Birth with Dignity Foundation. A Czerwińska, J Piotrowska. Raport: 20 lat–20 zmian Kobiety w Polsce w okresie transformacji 1989–2009. 2009; Fundacja Feminoteka, Heinrich Böll Foundation: Warszawa, 36–38.

- A Chełstowska. Zdrowie reproduckyjne: krótka historia aborcji. A Czerwińska, J Piotrowska. Raport: 20 lat–20 zmian Kobiety w Polsce w okresie transformacji 1989–2009. 2009; Fundacja Feminoteka, Heinrich Böll Foundation: Warszawa, 11–30.

- A Chełstowska. Aborcja i ruch pro-choice w Polsce. Antropologiczne badania w latach 2006–2008. 2008; Uniwersytet Warszawski: Warszawa.

- E Charkiewicz. Wprowadzenie do raportu w: Pielęgniarki. Protesty pielęgniarek i położnych w kontekście reform ochrony zdrowia. Raport Think Tanku Feministycznego. 3/2009. At: <www.ekologiasztuka.pl/pdf/f0086_TTFraport3_Pielegniarki-Kubisa.pdf. >.

- J Mishtal. Neoliberal reforms and privatisation of reproductive health services in post-socialist Poland. Reproductive Health Matters. 18(36): 2010; 56–66.

- Ustawa z dnia 27 kwietnia 1956 r. o warunkach dopuszczalności przerywania ciąży. Dziennik Ustaw z 1956 r. Nr 12, poz. 61, 1956.

- Kligman G. The politics of Duplicity. Controlling reproduction in Ceausescu's Romania. Berkeley, Los Angeles, London, 1998.

- E Maleck-Lewy, M Marx Ferree. Talking about women and wombs: the discourse of abortion and reproductive rights in the GDR during and after the Wende. S Gal, G Kligman. Reproducing Gender Politics, Publics, and Everyday Life after Socialism. 2000; Princeton University Press: Princeton.

- T Niemiec. Przerywanie ciąży. T Niemiec. Zdrowie kobiet w wieku prokreacyjnym 15–49 lat Polska 2006. 2007; Program Narodów Zjednoczonych ds. Rozwoju: Warszawa, 97–100.

- Orzeczenie Trybunału Konstytucyjnego z dnia 28 maja 1997 r. (Sygn. Akt K 26/96), 1997.

- K łwistow. Fenomen “obrony życia” w Polsce jako praktyka radykalnej prawicy (na przykładzie duchowej adopcji dziecka poczetego). 2007; Uniwersytet Warszawski: Warszawa.

- J Włodarczyk. Skąd się wziął syndrom?. Krytyka Polityczna. 7/8: 2005; 372–383.

- Penn S. Podziemie Kobiet. Warszawa; 2003.

- Uchwała Nadzwyczajnego II Krajowego Zjazdu Lekarzy z dnia 14 grudnia 1991 r. w sprawie Kodeksu Etyki Lekarskiej; 1991.

- Graff A. łwiat bez kobiet. Płeć w polskim życiu publicznym. Warszawa; 2005.

- CA Stabile. Shooting the mother: fetal photography and the politics of disappearance. PA Treichler, L Cartwright, C Penley. The Visible Woman: Imaging Technologies, Gender, and Science. 1998; New York University Press: New York.

- European Court of Human Rights. Judgement, Case of Tysiąc vs. Poland Application No.5410/03, 20 March 2007.

- European Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms, 1950.

- Prawa reprodukcyjne w Polsce. Skutki ustawy antyaborcyjnej. 2007; Federacja na Recz Kobiet i Planowania Rodziny: Warszawa.

- European Court of Human Rights. Application No.46132/08, Z against Poland, lodged 16 September 2008.

- Szlachetka M. Agata ma już dość. Gazeta Wyborcza. 11.06.2008.

- Matka Agaty. Matka Agaty: Chciałam legalnie, no i teraz mam. Gazeta Wyborcza; 2008.

- Sytuacja gospodarstw domowych w 2009 r. w świetle wyników badań budżetów gospodarstw domowych. Główny Urząd Statystyczny; 2010.

- Dunin K. Dwa tysiące na skrobankę. Wysokie Obcasy. 23.06.2001.

- R Fletcher. National crisis, supranational opportunity: the Irish construction of abortion as a European service. Reproductive Health Matters. 8(16): 2000; 35–44.

- Zespół Prasowy Komendy Głównej Policji. Materiały statystyczne: Zespół Prasowy Komendy Głównej Policji 2003–2006.

- Sprawozdanie Rady Ministrów z wykonania w roku 2005 ustawy z dnia 7 stycznia 1993 o planowaniu rodziny, ochornie płodu ludzkiego i warunkach dopuszczalności przerywania ciąży oraz skutkach jej stosowania. Warszawa; 2006.

- Siedlecka E. Gowin przeforsuje swoją ustawę o in vitro? Gazeta Wyborcza. 02.03.2009.

- Wiśniewska K. Albo in vitro, albo komunia. Gazeta Wyborcza. 2010 20.05.2010.

- Wiśniewska K. Biskupi: módlcie się o zakaz in vitro. Gazeta Wyborcza. 27.10.2010.

- Notatka prasowa z wysłuchania obywatelskiego “Zapłodnienie in vitro - szansa na godne rodzicielstwo”: Federacja na Rzecz Kobiet i Planowania Rodziny 23.02.2009.