Abstract

This article reports on the influence of HIV on sexual relations and childbearing decisions of 36 HIV-discordant couples, 26 in South Africa and 10 in Tanzania, recruited into an exploratory study through hospital antiretroviral treatment clinics and civil society organisations working with people living with HIV. Self-administered questionnaires were used to obtain social and demographic information, while couples' sexual relations and childbearing decisions were explored through in-depth, semi-structured individual and couple interviews. The majority of the HIV-positive partners were women, who were on antiretroviral treatment. Almost one-third of South African respondents and half of those in Tanzania reported experiences of tension related to HIV-discordance, while more than half of the South Africans and almost three-quarters of the Tanzanians reported that intimacy had been affected by their discordant status. Those without children were more likely to desire children (17/23) than those who already had children (16/44), although this desire was influenced by fear of HIV transmission to the negative partner and medical professional advice. The study points to the need for targeted information for HIV discordant couples, as well as couple counselling and support services.

Résumé

L'article décrit l'influence du VIH sur les relations sexuelles et la décision d'avoir ou non un enfant chez 36 couples sérodiscordants, 26 en Afrique du Sud et 10 en République-Unie de Tanzanie ; ils ont été recrutés dans une étude exploratoire par le biais de dispensaires de traitement antirétroviral et d'organisations de la société civile s'occupant de personnes qui vivent avec le VIH. Des questionnaires auto-administrés ont permis d'obtenir des informations sociales et démographiques, alors des entretiens approfondis semi-structurés individuels et en couple ont étudié les relations sexuelles et les décisions sur la paternité/maternité. La majorité des partenaires séropositifs étaient des femmes qui suivaient un traitement antirétroviral. Près d'un tiers des répondants sud-africains et la moitié des répondants tanzaniens ont fait état de tensions liées à la sérodiscordance, alors que plus de la moitié des Sud-Africains et près des trois quarts des Tanzaniens ont indiqué que leur statut discordant avait affecté leur intimité. Ceux qui n'étaient pas parents avaient plus de probabilités de désirer un enfant (17/23) que ceux qui en avaient déjà (16/44), même si ce désir était influencé par la crainte de la transmission du VIH au partenaire séronégatif et les conseils médicaux professionnels. L'étude souligne la nécessité d'une information ciblée pour les couples sérodiscordants, ainsi que des services de conseil et de soutien aux couples.

Resumen

En este artículo se informa sobre la influencia el VIH en las relaciones sexuales y decisiones de maternidad de 36 parejas sero-discordantes, 26 en Sudáfrica y 10 en Tanzania, reclutadas para un estudio exploratorio por clínicas hospitalarias de tratamiento antirretroviral y organizaciones de la sociedad civil que trabajan con personas que viven con VIH. Se utilizaron cuestionarios autoadministrados para obtener información social y demográfica, mientras que las relaciones sexuales y decisiones de maternidad de las parejas fueron exploradas mediante entrevistas a profundidad semiestructuradas, tanto individuales como en pareja. La mayoría de las parejas VIH-positivas eran mujeres que estaban recibiendo tratamiento antirretroviral. Casi una tercera parte de las personas entrevistadas en Sudáfrica y la mitad de aquéllas en Tanzania relataron experiencias de tensión relacionada con la sero-discordancia, mientras que más de la mitad en Sudáfrica y casi tres cuartas partes en Tanzania relataron que la intimidad había sido afectada por su estado discordante. Aquéllas sin hijos tendían más a desearlos (17/23) que las que ya tenían hijos (16/44), aunque este deseo era influenciado por el temor de transmitir el VIH a la pareja negativa y por consejos de profesionales médicos. El estudio señala la necesidad de ofrecer información, consejería y servicios de apoyo a las parejas sero-discordantes.

Sub-Saharan Africa remains the region most heavily affected by the HIV pandemic, accounting for 71% of all new HIV infections in 2008. Approximately 22.4 million Africans were living with HIV in 2008, reflecting the combined effects of continued high rates of new HIV infections and the beneficial impact of antiretroviral therapy.Citation1 South Africa and Tanzania, the two countries that form the backdrop to this study, are experiencing generalised HIV epidemics.Citation1 In South Africa, estimated HIV prevalence among persons aged 15–49 years is 16.9%, with an estimated 5.7 million people living with HIV.Citation1Citation2 In Tanzania, estimated HIV prevalence is 5.7% with an estimated 1.3 million people living with HIV.Citation1Citation3 In both countries, women are disproportionately affected by the epidemic.Citation1Citation2Citation3

In the generalised epidemics in Africa, a large proportion of new HIV infections occur between couples in established relationships, making discordance a major contributor to the spread of HIV.Citation1Citation4Citation5 Studies in sub-Saharan Africa have shown a prevalence of HIV discordance among couples of 3–20% in the general populationCitation6Citation7Citation8 and 20–35% among couples with one partner seeking HIV care.Citation9Citation10Citation11 A multi-site HIV prevention trial at eastern and southern Africa sites found a prevalence of HIV discordance of 27% in 1,126 couples screened in South Africa and 14% in 477 couples screened in Tanzania.Citation12 However, with the exception of participants tested for HIV in a research context, many individuals living in resource-poor countries are unaware of their own and their partners' HIV status.Citation12

Although discordant couples account for a substantial proportion of new infections, neither programmes nor testing and counselling are geared for such couples.Citation1Citation4 A key challenge for HIV-discordant couples is minimising the risk of HIV transmission to their negative partner(s) and to any children conceived.Citation13 This has led to increasing attention to, and advocacy for, the provision of reproductive assistance (such as sperm washing or in-vitro fertilisation (IVF)) to reduce the risks of HIV transmission and to satisfy the desire for children with little or no risk.Citation14Citation15Citation16Citation17Citation18Citation19 However, providing reproductive assistance to discordant couples is often not feasible in resource-constrained settings and there has been little policy and programmatic focus or guidance to ensure access to these sexual and reproductive health services within a human rights framework.Citation14Citation15Citation16Citation17Citation18Citation19

In 2007, the Global Network of People Living with HIV/AIDS (GNP+) requested the South African Human Sciences Research Council (HSRC) to conduct an exploratory study to gather information about the psychosocial experiences of couples in long-term HIV sero-discordant relationships. The purpose of the study was to inform the HIV prevention and advocacy programmes of GNP+ and others of the challenges faced by individuals in discordant relationships, and the support that partners are able to provide to one another to protect their mutual health. This article reports on the sexual relations and childbearing decisions of HIV-discordant couples in South Africa and Tanzania. It is based on the technical report produced with and for GNP+.Citation23

Methods

The study was conducted in South Africa (Johannesburg and Cape Town), Tanzania (Dar es Salaam) and Ukraine (Kiev, Rivne and Ivano-Frankovsk) during 2008.Footnote* Inclusion of couples in sub-Saharan African countries was the top priority in view of the high prevalence of HIV discordance. Given the global focus of GNP+, the initial intention was also to include some couples from a number of other countries. This did not materialise due to the lack of simple and inexpensive means of recruiting HIV-discordant couples; access to an appropriate in-country research ethics committee for study approval; contacts with, and availability of, qualified people fluent both in English and the local languages to conduct the interviews; and budgetary constraints.

The population of interest was couples in long-term sexual relationships, in which one partner was HIV-positive, and the other HIV-negative. The study was limited to HIV-discordant couples, regardless of sexual orientation, who had been in a sexual relationship and aware of the HIV-positive partner's status for at least a year. Exclusion criteria included: couples who were in a recently established relationship; people who had recently been diagnosed with HIV; and people living with HIV who had only disclosed their HIV status to their partner recently (or who had not disclosed). Partners making up the couple were not required to be monogamous, living together or to have formalised their relationship through marriage or a civil union. No HIV testing or documentation was used to confirm the HIV status of either the HIV-positive or the HIV-negative partner.

In each country, ethical approval was obtained. In South Africa, 26 discordant couples were recruited through health care providers at hospital antiretroviral treatment clinics and civil society organisations focusing on or working with people with HIV. In Tanzania, ten couples were recruited through the African Medical and Research Foundation (AMREF). Potential participants were approached by a health care provider or support group coordinator who was already aware of the couple's discordant status, in order to protect their privacy and respect the confidentiality of their HIV status. Researchers contacted potential participants after they had given permission to be contacted. Individual, written, voluntary informed consent was obtained and the interviews only proceeded if both partners agreed to participate in the study. The consent forms and interview guides were developed in English, and translated into appropriate local languages by the trained interviewers (isiXhosa, isiZulu and Sesotho in South Africa and Swahili in Tanzania). The back translation was checked by an HSRC or AMREF staff member who was familiar with the relevant language.

Couples were interviewed by trained interviewers in their home or at a suitable, convenient venue and in their language of choice. Each participant completed a brief, structured, self-administered questionnaire that focused on demographic characteristics, history and duration of the current relationship, HIV testing, health, and number of children from current or previous relationships. Not all respondents answered every question. Each participant was also interviewed individually on experiences of conflict or tension in the relationship; whether and how discordance affected their intimacy and sex life; “safe sex” practices, which were defined as steps (e.g. condom use) to prevent the spread of HIV or other sexually transmitted infections; and childbearing decisions. Lastly, a semi-structured couple interview explored, inter alia, the couple's experiences of practising safer sex and their recommendations for information, support or services to HIV-discordant couples. Due to logistical and budgetary constraints, only three interviews were tape recorded. In the case of all other interviews, the interviewers took detailed notes of each interview, and checked the accuracy of the information with participants. The questionnaire completion and interviews with each couple took between two and three hours. A voucher, equivalent in value to US $15, was given to each couple at the end of the interviews to thank them for their participation.

The self-administered questionnaires were coded, using a standard coding sheet and analysed using Stata Version 10. Information from the semi-structured interviews was coded and included in the quantitative analysis. The qualitative interviews from South Africa and Tanzania were analysed using thematic content analysis. The steps consisted of: open coding using the participants' own words and phrases and without pre-conceived notions or classification; examining language used by each partner or couple; comparing what each individual said about their relationship with what they said when they were interviewed together; categorising the information from all the interviews and finally theoretical coding in which open codes and categories were compared to generate an analytic schema and to interpret the findings.Citation24

Results

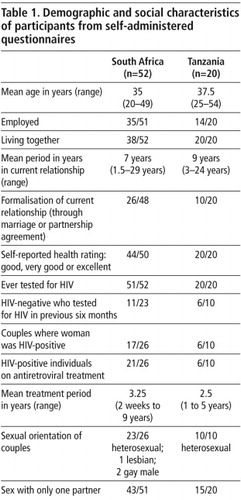

The demographic and background characteristics of the participants are shown in Table 1

.HIV-discordance, intimacy and sexual relations

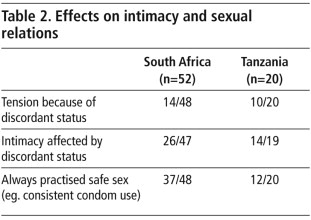

In South Africa 14 of 48 respondents and in Tanzania 10 of 20 respondents reported experiences of tension in the relationship, while 26/47 from South Africa and 14/19 from Tanzania reported that intimacy had been affected by their discordant status (Table 2

).Tensions arose because of fear of infecting the negative partner, real or perceived infidelity, and problems experienced from consistent condom use. Fear of infecting the negative partner was a recurring theme in the interviews, especially among the HIV-positive partners.

“In the beginning, I was more concerned about safe sex, and I had this fear of infecting my partner. We have been trying to find a middle ground, and it has become less of an issue with time.” (HIV-positive man, couple 23, SA)

“We experienced tension… I was worried that I would also be infected with HIV.” (HIV-negative man, couple 1, TZN)

“Yes…. there has been a bit of tension which I can relate to the lack of trust. I was also asked [by my partner] to give a list of people I've ever slept with, which I declined.” (HIV-positive man, couple 6, SA)

“We experience conflict because my partner who is positive, continues to have relationships with positive girlfriends.” (HIV-negative woman, couple 3, TZN)

“It is difficult to practise safe sex with your day-to-day partner. Changing from not using a condom to using a condom caused a lot of interference in our sex life.” (Couple 7, TZN)

“When I first found out, I was not ready to die and that was and is still my driving force [to use condoms]… but there is this natural instinct to have unsafe sex and it's why most men don't wear condoms. Intimacy and having your partner ‘all in one’ does play very heavily on your mind versus having to use a condom.” (HIV-positive partner, couple 24, SA)

“I think condom use is easier because the HIV virus is constantly there… and therefore it is a must to use condoms… and there are also rules about trust.” (HIV-negative partner, couple 24, SA)

“Sex has decreased from six times per month to two times per month. Using a condom has been a challenge as my partner does not find enough satisfaction.” (HIV-negative man, couple 7, TZN)

“It has limited our relationship in some ways, such as not brushing teeth for fear of bleeding gums. If the condom is not there, no sex; I am hyper-conscious of protecting him.” (HIV-positive woman, couple 5, SA)

“[The relationship] is good, but sometimes it's very difficult in terms of using condoms every day. Sometimes we feel like we don't want to use one because we still want to have children, but I am scared to infect my partner.” (Couple 3, SA)

“Negative people enjoy sex, but the discordant couple does not enjoy sex because of a condom. We don't know what to do to get a child…” (Couple 5, TZN)

Desire for children and reproductive decisions

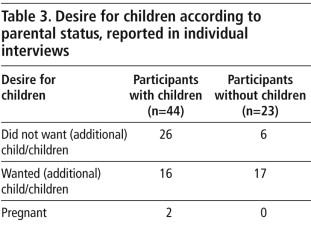

Couples' intentions to have children were influenced by fear of infecting the HIV-negative partner; reconciling the conflicting desires of the two partners; medical professional advice; and the lack of availability and affordability of alternatives to natural conception. Nevertheless, the majority of participants who did not have any children desired to have children (Table 3

). The desire for children sometimes conflicted with HIV prevention for the negative partner.“I am negative, and I need to have a child. I feel that using a condom can hinder us from getting a child.” (HIV-negative man, couple 1, TZN)

“We would love to have children in future. We are a bit reluctant to have children because my partner is scared that he may infect me.” (HIV-negative woman, couple 17, SA)

HIV-positive woman: “I do not want children because of my HIV-positive status. He does not want to talk about it. I am not sure if he knows about masturbation (if we go for the IVF route)… I don't want shame and embarrassment for him, and that's why it is not discussed… I am not sure about children. The only reason I consider them is because he has done a lot for me… He is one of the first people to show unconditional support, despite my status. I would feel guilty and selfish for not wanting kids.”

HIV-negative man: “Children are an issue… We plan to have children, and maybe she will fall pregnant before the wedding.” (Couple 5, SA)

HIV-positive man: “Our discordant status affects our relationship, because I have children and my partner does not have children. Sometimes my partner does not want to use a condom, but I encourage her to use a condom. I do not have children with her.”

HIV-negative woman: “The issue of condom use affects the relationship with my partner. He has enough knowledge of HIV, but sometimes refuses to use a condom. I plan to have children in future.” (Couple 5, TZN)

Couples' recommendations of useful services

Only two of the ten Tanzanian couples requested counselling and support services to cope with discordance, but this could be because the Tanzanian couples were already part of AMREF's support groups for discordant couples. In contrast, nine out of the 26 South African couples expressed the need for counselling and support services.

“There are lots of discordant couples, but they are not visible. The system does not allow for [discordant] relationships and for disclosure… Assistance to live positively is lacking. There must be an organisation that supports discordant relationships, so that one goes into [the relationship] with open eyes. There must be a support structure… It should be government. We need to know about options [to have children] and to support one another.” (Couple 4, SA)

“We would like to have more information on healthy lifestyles, nutrition, better sex life, and how to deal with emotions that come with being a sero-discordant couple. We would like to live as normal a life as possible.” (Couple 7, SA)

“We would like to have information on support groups… there is no information on sero-discordant couples, which discourages other couples to come out as sero-discordant couples, because most people think that it is not possible to have a relationship with an HIV-positive partner.” (Couple 9, SA)

“More education should be given to the community. That will help them to understand the problem [of HIV discordance] and how to cope with it. It would be good to organise training for discordant couples that will empower them to talk to society about HIV.” (Couple 6, TZN)

Discussion

In the last decade, research on HIV discordance has been largely dominated by biomedical studies on the epidemiology of discordance and HIV transmission factors.Citation5Citation12Citation25Citation26 The psychosocial aspects of HIV-discordant relationships have received insufficient attention, evidenced by the lack of any mention of HIV-discordance in the 2008 International AIDS conference report and a 2009 International AIDS Society review of the state of HIV and AIDS social and political science research.Citation27Citation28 This exploratory study found that among 36 purposively selected couples in South Africa and Tanzania, HIV and their HIV-discordant status were ever-present issues, influencing their sexual relations and childbearing decisions.

These issues are often not addressed as part of HIV treatment and care services. Encouraging dialogue among couples about the effects on intimacy, sexual risks and providing couples with information, support and condom supplies, have been found to improve their relationships and to facilitate long-term conjugal condom use.Citation4 A WHO study in six African countries found that ongoing encouragement by health care providers facilitated condom use.Citation29 The introduction of couple voluntary counselling and testing services has also been shown to have an overall positive impact on condom use among couples in several African cities.Citation29Citation30Citation31Citation32

The ability to choose whether and when to have children are well-established features of reproductive health, well-being and human rights.Citation21Citation33Citation34Citation35Citation36 In this exploratory study, the majority of couples without children desired to have children, supporting the findings of other studies regarding the desire for children among people living with HIV.Citation33Citation37Citation38Citation39Citation40Citation41 An Ethiopian study of 460 HIV-positive individuals reported strong associations between parity, age, marriage or current relationship, and the desire to have children.Citation41 A survey among 114 mutually disclosed sero-discordant couples in Kampala, Uganda found that 59% desired to have children.Citation37 Factors influencing fertility desire included the belief that their partner wanted children, young age, relatives' expectations and knowledge of treatment effectiveness.Citation37

Similar to other studiesCitation33Citation39 our study shows that reproductive intentions of discordant couples are shaped by complex personal, interpersonal, medical and health care factors. The desire and intention to have children often conflict with safer sex imperatives, preventing HIV transmission, and other HIV-related concerns. However, these concerns may be overridden by the desire to experience biological parenthood, and influenced by social and cultural values that encourage childbearing and parenthood.

In both countries the exploratory study points to gaps in policy and programmes for discordant couples, although the majority of couples in both countries expressed a need for information, counselling and support services. Services that focus on couples, rather than individuals, are currently not widely available and tend to be small-scale and pilot projects.Citation4Citation38Citation42Citation43 Neither of the two study countries had policies on repeat HIV testing of HIV-negative partners in discordant relationships.Citation2Citation3Citation44Citation45 Sexual and reproductive health needs are frequently not addressed by health care providers, and it is difficult for HIV-positive women to get appropriate information and support from family planning clinics or maternity services.Citation20Citation22Citation36Citation46Citation47 Health worker attitudes and behaviour play a major role in the sexual health and childbearing decisions of people with HIV.Citation36Citation48Citation49Citation50 Policy debates have also largely ignored the sexuality of people living with HIV, with programmes limited to helping pregnant women avoid transmitting the virus to their children.Citation21Citation43Citation51

The use of quantitative and qualitative methods, and interviews with each partner separately as well as the partners together, revealed contrasting perspectives between partners. Restricting eligibility to discordant couples who were in long-term relationships was also a strength of the study, as participants had had time to work through the challenges of disclosure and choices around safer sex and having children. Limitations of our study include the limited sample size and the recruitment of couples through health professionals and NGOs that provide services to people with HIV. Participants were likely to have had better access to services and to have been better informed than discordant couples in general. This limits the generalisability of our findings. Lastly, information on sensitive topics was self-reported, thus there is likely to have been some social desirability bias in participants' responses.

Recommendations

Policies and programmes for discordant couples that promote the health of both partners, and provide support in addressing the challenges of being in a discordant partnership should be developed. These should include the meaningful involvement of discordant couples and be based on an understanding of how HIV services influence reproductive intentions. Further studies should be conducted to provide information on healthy living within the context of discordant relationships.

Health care systems and health care providers should be more responsive to the needs of discordant couples, with ongoing sexual health advice, information and counselling on safer sex and condom use. Health care providers should be oriented to the needs of couples, rather than individuals only and should assist couples to make informed reproductive decisions.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank the couples for valuable insights and the following individuals for their assistance: in South Africa – Debbie Mopedi, Nico Jacobs, Jonathan Berger, Prof Jeffrey Wing, Drs Alan Karstaedt, Ashraf Coovadia, Duane Blaauw; in Tanzania – Blanche Pitt, Dr Benedicta Mduma, Cayus Mrina, Scholastica Spendi, Suzan Kipuyo. Aspects of the overall study have been presented at the 2008 Wits Faculty of Health Sciences research day and the 2009 South African AIDS conference. The World Health Organization funded the Global Network of People Living with HIV (GNP+) to undertake the study. The views presented in this report are those of the authors and do not represent the decisions, policy or views of GNP+ or WHO.

Notes

* As only a summary of the interviews conducted in Ukraine was available, this article focuses on the results from South Africa and Tanzania.

References

- UNAIDS World Health Organization. 2009 AIDS Epidemic Update. 2009; UNAIDS/WHO: Geneva.

- Republic of South Africa. Country progress report on the Declaration of Commitment on HIV/AIDS: 2010 report. 2010; Department of Health: Pretoria.

- Tanzania Commission for HIV and AIDS. United Republic of Tanzania: UNGASS reporting for 2010. 2010; TACAIDS: Dar es Salaam.

- A Desgrées-du-Loû, J Orne-Gliemann. Couple-centred testing and counselling for HIV serodiscordant heterosexual couples in sub-Saharan Africa. Reproductive Health Matters. 16(32): 2008; 151–161.

- B Guthrie, G de Bruyn, C Farquhar. HIV-1-discordant couples in sub-Saharan Africa: explanations and implications for high rates of discordancy. Current HIV Research. 5: 2007; 416–429.

- L Carpenter, A Kamali, A Ruberantwari. Rates of HIV-1 transmission within marriage in rural Uganda in relation to the HIV sero-status of the partners. AIDS. 13: 1997; 1083–1089.

- D De Walque. HIV infection among couples in Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Ghana, Kenya and Tanzania. 2006; World Bank: Washington.

- M Lurie, B Williams, K Zuma. Who infects whom? HIV-1 concordance and discordance among migrant and non-migrant couples in South Africa. AIDS. 17: 2003; 2245–2252.

- J N'Gbichi, K De Cock, V Batter. HIV status of female sex partners of men reactive to HIV-1, HIV-2 or both viruses in Abidjan, Côte d'Ivoire. AIDS. 9: 1995; 951–954.

- W Were, J Mermin, N Wamai. Undiagnosed HIV infection and couple HIV discordance among household members of HIV-infected people receiving antiretroviral therapy in Uganda. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome. 43: 2006; 91–95.

- J White, D Melvin, C Moore. Parental HIV discordancy and its impact on the family. AIDS Care. 9: 1997; 609–615.

- J Lingappa, B Lambdin, E Bukusi. Regional differences in prevalence of HIV-1 discordance in Africa and enrolment of HIV-1 discordant couples into an HIV-1 prevention trial. PLoS One. 3(1): 2008; e1141.

- A Thornton, F Romanelli, J Collins. Reproduction decision-making for couples affected by HIV: a review of the literature. Topical HIV Medicine. 12(2): 2004; 61–67.

- P Barreiro, A Duerr, K Beckerman. Reproductive options for HIV-discordant couples. AIDS Review. 8(3): 2006; 158–170.

- S Nosarka, CF Hoogendijk, TI Siebert. Assisted reproduction in the HIV-discordant couple. South African Medical Journal. 97(1): 2007; 24–26.

- M Sauer. Sperm washing techniques address the fertility needs of HIV-sero-positive men: a clinical review. Reproductive Biomed Online. 10(1): 2005; 135–140.

- MV Sauer, PL Chang. Posthumous reproduction in a human immunodeficiency virus-discordant couple. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 185(1): 2001; 252–253.

- S Sunderam, L Hollander, M Macaluso. Safe conception for HIV discordant couples through sperm-washing: experience and perceptions of patients in Milan, Italy. Reproductive Health Matters. 16(31): 2008; 211–219.

- AE Semprini, E Augusto, P Levi-Setti. Insemination of HIV-negative women with processed semen of HIV-positive partners. Lancet. 340: 1992; 1317–1319.

- E Bell, P Mthembu, S O'Sullivan. Sexual and reproductive health services and HIV testing: perspectives and experiences of women and men living with HIV and AIDS. Reproductive Health Matters. 15(29 Suppl): 2007; 113–135.

- GNP+ ICW Young Positives, et al. Advancing the Sexual and Reproductive Health and Human Rights of People Living with HIV: A Guidance Package. 2009; GNP+: Amsterdam.

- S Gruskin, L Ferguson, J O'Malley. Ensuring sexual and reproductive health for people living with HIV: an overview of key human rights, policy and health systems issues. Reproductive Health Matters. 15(29 Suppl): 2007; 4–26.

- L Rispel, C Metcalf, K Moody. HIV- discordant couples: insights from South Africa, Tanzania, and Ukraine. 2009; GNP+: Amsterdam.

- B Mostyn. The content analysis of qualitative research data: a dynamic approach. M Bressner, J Brown, D Conta. The Research Interview: Uses and Approaches. 1985; Academic Press: Orlando, 115–145.

- E Freeman, J Glynn. Factors affecting HIV concordancy in married couples in four African cities. AIDS. 18: 2004; 1715–1721.

- R Gray, M Wawer, R Brookmeyer. Probability of HIV transmission per coital act in monogamous, heterosexual, HIV1-discordant couples in Rakai, Uganda. Lancet. 357: 2001; 1149–1153.

- S Kippax, M Holt. The state of social and political science research related to HIV: a report for the International AIDS Society. 2009; International AIDS Society: Geneva.

- R Kort. XVII International AIDS Conference: From Evidence to Action. Introduction. Journal of International AIDS Society. 12(Suppl 1): 2009; S1.

- J Cleland, MM Ali, I Shah. Trends in protective behaviour among single vs married young women in sub-Saharan Africa: the big picture. Reproductive Health Matters. 14(28): 2006; 17–22.

- S Allen, J Meinzen-Derr, M Kautzman. Sexual behavior of HIV-discordant couples after HIV counseling and testing. AIDS. 17: 2003; 733–740.

- S Allen, J Tice, P Van de Perre. Effect of sero-testing with counselling on condom use and sero-conversion among HIV-discordant couples in Africa. British Medical Journal. 304: 1992; 1605–1609.

- C Kamenga, RW Ryder, M Jingu. Evidence of marked sexual behavior change associated with low HIV-1 seroconversion in 149 married couples with discordant HIV-1 serostatus: experience at an HIV counselling center in Zaire. AIDS. 5(1): 1991; 61–67.

- D Cooper, J Harries, L Myer. “Life is still going on”: reproductive intentions among HIV-positive woman and men in South Africa. Social Science and Medicine. 65: 2007; 274–283.

- D Cooper, C Morroni, P Orner. Ten years of democracy in South Africa: documenting transformation in reproductive health policy and status. Reproductive Health Matters. 12: 2004; 70–85.

- GNP+, UNAIDS. Positive Health, Dignity and Prevention: Technical Consultation Report. Technical Consultation on “Positive Prevention”; 27–28 April 2009. Hammamet, Tunisia.

- S Gruskin, R Firestone, S MacCarthy. HIV and pregnancy intentions: do services adequately respond to women's needs?. American Journal of Public Health. 98(10): 2008; 1746–1750.

- J Beyeza-Kashesya, AM Ekstrom, F Kaharuza. My partner wants a child: a cross-sectional study of the determinants of the desire for children among mutually disclosed sero-discordant couples receiving care in Uganda. BMC Public Health. 10: 2010; 247.

- D Cooper, J Moodley, V Zweigenthal. Fertility intentions and reproductive health care needs of people living with HIV in Cape Town, South Africa: implications for integrating reproductive health and HIV care services. AIDS and Behaviour. 2009. DOI 10.1007/s10461-009-9550-1.

- IF Hoffman, FEA Martinson, KA Powers. The year-long effect of HIV positive test results on pregnancy intentions, contraceptive use and pregnancy incidence among Malawian women. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome. 47: 2008; 477–483.

- A Kaida, F Laher, SA Strathdee. Childbearing intentions of HIV-positive women of reproductive age in Soweto, South Africa: the influence of expanding access to HAART in an HIV hyper-endemic setting. American Journal of Public Health. 2009. DOI 10.2015/AJPH2009.177469.

- W Tamene, M Fantahun. Fertility desire and family-planning demand among HIV-positive women and men undergoing antiretroviral treatment in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. African Journal of AIDS Research. 6: 2007; 223–227.

- International HIV/AIDS Alliance. Positive prevention: HIV prevention with people living with HIV. London, 2007.

- L Myer, M Rabkin, EJ Abrams. Focus on women: linking HIV care and treatment with reproductive health services in the MTCT-Plus Initiative. Reproductive Health Matters. 13(25): 2005; 136–146.

- Republic of South Africa. Progress report on the Declaration of Commitment on HIV and AIDS: Reporting period January 2006–December 2007. 2008; Department of Health: Pretoria.

- Tanzania Commission for AIDS. UNGASS Country Progress report: Tanzania Mainland: Reporting period January 2006–December 2007. 2008; TACAIDS: Dar es Salaam.

- G De Bruyn, N Bandezi, S Dladla. HIV-discordant couples: an emerging issue in prevention and treatment. South African Journal of HIV Medicine. 23: 2006; 25–28.

- R Feldman, C Maposhere. Safer sex and reproductive choice: findings from “Positive Women: Voices and Choices” in Zimbabwe. Reproductive Health Matters. 11(22): 2003; 162–173.

- S Kanniappan, MJ Jeyapaul, S Kalyanwala. Desire for motherhood: exploring HIV positive women's desires, intentions and decision-making in attaining motherhood. AIDS Care. 20(6): 2008; 625–630.

- V Paiva, EV Filipe, N Santos. The right to love: the desire for parenthood among men living with HIV. Reproductive Health Matters. 11(22): 2003; 91–100.

- L Panozzo, M Battegay, A Friedl. The Swiss Cohort Study. High-risk behaviour and fertility desires among heterosexual HIV positive patients with a sero-discordant partner – two challenging issues. Swiss Medical Weekly. 132(7): 2002; 124.

- J Harries, D Cooper, L Myer. Policy maker and health care provider perspectives on reproductive decision-making amongst HIV-infected individuals in South Africa. BMC Public Health. 7: 2007; 282. DOI: 10.1186/471-2458-7-282.