Abstract

Aid from Denmark, Finland, Germany, Netherlands, Norway, Sweden and UK provides essential support for sexual and reproductive health and rights. Recent research, however, has revealed conflicting values in how their aid is programmed, resulting in a reduction in both quantity and quality of support provided. The strong commitment of these donors to country ownership has, in practice, invested decision-making primarily with developing country governments, with civil society playing a much weaker role. In most countries, strong civil society organizations are needed for effective advocacy of sexual and reproductive health and rights and health service delivery, and the restricted role of this sector has slowed progress towards universal access to reproductive health. The research documented also that these donors' respect for the autonomy of multilateral health agencies has resulted in some reluctance to encourage more attention to SRHR. In addition, their commitment to “impact” has not translated into the incorporation of relevant and practical outcome measures by which to assess the results of their investments. Almost 80% of the money they earmark for sexual and reproductive health and rights goes to UNFPA, underscoring its critical role. This article recommends donor support for a stronger civil society role in the design, implementation and evaluation of SRHR funding; strengthening civil society so that it can successfully undertake this role; use of better outcome measures to assess impact; and active support for UNFPA to implement the recommendations of recent external reviews.

Résumé

L'aide accordée par l'Allemagne, le Danemark, la Finlande, la Norvège, les Pays-Bas, le Royaume-Uni et la Suède est essentielle pour la santé et les droits génésiques. Pourtant, de récentes recherches ont révélé des valeurs conflictuelles dans la programmation de l'aide, aboutissant à une réduction de la quantité et la qualité du soutien prodigué. Attachés à une prise en charge nationale, les donateurs ont, dans la pratique, confié l'essentiel de la prise de décision aux gouvernements des pays en développement, la société civile jouant un rôle beaucoup plus modeste. La plupart des pays requièrent de solides organisations de la société civile pour un plaidoyer efficace en faveur de la santé et des droits génésiques et de la prestation des services de santé, et le rôle restreint de ce secteur a ralenti les progrès vers l'accès universel à la santé génésique. La recherche a aussi montré que le respect des donateurs pour l'autonomie des institutions multilatérales de santé a créé des réticences à encourager une attention accrue à la santé et aux droits génésiques. De plus, leur intérêt pour « l'impact » ne s'est pas concrétisé par l'inclusion de mesures pratiques et pertinentes des résultats pour évaluer les suites de leurs investissements. Près de 80% des fonds qu'ils allouent à la santé et aux droits génésiques sont réservés au FNUAP, soulignant le rôle fondamental du Fonds. L'article recommande aux donateurs de soutenir un rôle élargi de la société civile dans la conception, l'utilisation et l'évaluation du financement de la santé et des droits génésiques ; renforcer la société civile pour qu'elle puisse assumer ce rôle avec succès ; utiliser de meilleures mesures des résultats pour évaluer l'impact ; et soutenir activement le FNUAP pour appliquer les recommandations des études externes récentes.

Resumen

La ayuda financiera de Dinamarca, Finlandia, Alemania, Holanda, Noruega, Suecia y el Reino Unido brinda apoyo esencial para la salud y los derechos sexuales y reproductivos. Sin embargo, recientes investigaciones revelaron valores conflictivos en cuanto a la programación de dicha ayuda, que resulta en una reducción de la cantidad y calidad del apoyo brindado. El gran compromiso de estos donantes para con la apropiación nacional, en práctica, ha invertido la toma de decisiones principalmente con los gobiernos de los países en desarrollo, y la sociedad civil ha desempeñado una función mucho más pasiva. En la mayoría de los países, se necesitan dedicadas organizaciones de la sociedad civil para abogar eficazmente por la salud y los derechos sexuales y reproductivos y la prestación de servicios de salud. La restringida función de este sector ha retrasado los avances hacia el acceso universal a la salud reproductiva. Las investigaciones documentaron que, debido al respeto de estos donantes por la autonomía de instituciones multilaterales de salud, ha habido renuencia a fomentar más atención a la salud y los DD. SS. RR. Además, su compromiso por “tener impacto” no se ha traducido en la incorporación de medidas de resultados pertinentes y prácticos por las cuales se puedan evaluar los resultados de sus inversiones. Casi el 80% de los fondos destinados para la salud y los derechos sexuales y reproductivos van a UNFPA, lo cual recalca su crucial función. En este artículo se recomienda el apoyo de los donantes para fomentar mayor participación de la sociedad civil en diseñar, aplicar y evaluar los fondos para la salud y los DD. SS. RR.; fortalecer a la sociedad civil para que logre asumir esta función; utilizar mejores medidas de los resultados para evaluar el impacto; y apoyar a UNFPA en la aplicación de las recomendaciones realizadas en recientes revisiones externas.

Seven European countries (Denmark, Finland, Germany, Netherlands, Norway, Sweden and United Kingdom), collectively known as the “like-minded”, have been staunch supporters of international sexual and reproductive health and rights (SRHR) development cooperation over many years. Although they do not have identical approaches to official development assistance (ODA), they stand alone in being willing to embrace the controversial elements of SRHR, such as promotion of safe abortion and services to youth, as well as more mainstream areas, such as the unmet need for contraception. Although many of these countries now have more conservative governments than in the recent past, there is as yet no tangible evidence indicating any reorientation of their SRHR ODA priorities.

Recent reports, commissioned by the Hewlett Foundation, reviewed approaches to SRHR ODA in each of the seven like-minded countries.Citation1–7 These analyses revealed that conflicting values shape the SRHR ODA policies and practices of these donors and that to varying extents, this dissonance is reducing the impact of their aid investments. This article synthesizes the major findings of the reports, and proposes ways in which these very important donors can use their investments to make a more tangible and positive impact on the lives of hundreds of millions of the world's most vulnerable women.

The reports document conflicts in values that reflect the well-known problem donors have of wanting to foster autonomy in execution without losing accountability for the results. These seven European donors are committed to “country ownership”, through which recipient countries have substantial autonomy in the allocation of aid between sectors (e.g. health, agriculture) and within sectors (e.g. within health to SRHR or malaria prevention). This philosophy also extends to multilateral organizations in the United Nations (UN), and indeed the studies documented that the like-minded donors do not want to be perceived as being overly directive about how their money should be spent or even overly inquisitive about how it is spent.Footnote* At the same time, they are also deeply committed to showing a concrete impact of their ODA investments.

The like-minded donors acknowledge and respect the important role that civil society plays in development. However, during ODA negotiations at the developing country level, civil society rarely has a role powerful enough to significantly affect resource allocation decisions. This is particularly unfortunate since experience has shown it is civil society rather than developing country governments that lead the way for improving sexual and reproductive health and rights, especially with regard to making abortion safe and legal, services to sexually active unmarried people, and promoting and protecting sexual rights.

It is particularly important to recognise and resolve this conflict, because of the increasing concern among donor country governments (and their taxpayers) that decades of development assistance needs to show tangible, measurable results, and that continuing the status quo is not acceptable. Arising from the broader push for fiscal austerity following the near collapse of the international banking system, this concern has only intensified.

This article:

| • | describes the country studies upon which this article is based, | ||||

| • | briefly reviews the history of major ODA developments that have shaped how the like-minded programme their SRHR funds and why this has led to value conflicts, | ||||

| • | summarizes data from the studies about how resources flow to SRHR and the amount of these funds, and | ||||

| • | discusses the recommendations made by experts within each of the countries about ways to improve the impact of SRHR ODA investments by resolving the conflict between the values of autonomy and accountability. | ||||

Seven-country study of the like-minded European donors

Between May and December 2011, the Hewlett Foundation commissioned experts from Denmark, Finland, Germany, Netherlands, Norway, Sweden and United Kingdom to undertake documentation research concerning the SRHR ODA policies and practices of these governments, focusing on aid to sub-Saharan Africa.Citation1–7 These reports were based on interviews with donor agencies, parliamentarians, NGOs, think tanks and, in some places, the media in those countries. Each study reviewed the major policies underlying SRHR ODA, and how decisions were made on this topic at the political/strategic and ministerial levels. Using primarily published data, but also some unpublished sources, each study attempted to estimate the amount of money these funders spent on SRHR ODA. A draft copy of each report was circulated to the interviewees involved and their corrections and comments were integrated into the final versions. Each interviewee was asked to suggest ways in which their country's SRHR ODA could have more impact, and these are discussed at length in the final reports. This article synthesizes the main findings and recommendations from the reports that have relevance for all seven countries.

Policy frameworks for SRHR ODA: a brief history

The SRHR ODA policies documented in the seven countries did not emerge in a vacuum. These donors were among the first to recognize that projects in the South designed primarily by the North were less likely to succeed than those initiated and strongly supported by the developing countries concerned. Similarly, they were conscious of the burden placed on developing countries governments of numerous, often redundant, teams of donors and technical experts negotiating projects in an uncoordinated and fragmented fashion. This situation was the norm up until the 1990s, when different modalities came into being. These aimed to put the developing country rather than the donor in the driver's seat, by shifting from supporting vertically-focused projects to funding entire sectors such as health, and even national budgets, with the developing country deciding how to allocate the resources.Footnote* , Footnote†

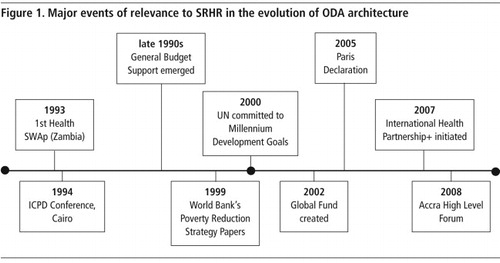

shows key milestones in the aid architecture that have had particular relevance for sexual and reproductive health and rights. The first shift from vertical projects to supporting an entire health system (the sector-wide approach, or SWAp) was made in Zambia almost 20 years ago. This was a significant step in that, at least in principle, decision-making went to the country to determine how to allocate health-related ODA funds. In the case of Zambia, the Ministries of Finance and Health, in consultation with the donors, would determine its own health funding priorities.Citation11 Unfortunately, an evaluation of this programme found that the hoped-for progress had not been achieved, particularly at the district level.

In 1994, the UN International Conference on Population and Development (ICPD) Programme of Action called for provision of a full range of sexual and reproductive health services, “as far as possible based on national sovereignty and in conformity with internationally recognized human rights”.Citation12 The new donor modalities only took root after ICPD, however. General Budget Support emerged in the late 1990s, for example, and expanded the concept of sector-wide support to include whole national budgets. Concerns in the SRHR field that sexual and reproductive health and rights would not be prioritised at country level because they were controversial proved true in many cases.

In 1999 the World Bank began to work with developing countries to produce Poverty Reduction Strategy Papers (PRSPs) upon which, in theory, all development assistance would be based. Although many PRSPs did identify family planning and reproductive health as a priority, and some even took into account the effect of demographic factors on development, in practice, this generally did not result in more tangible or traceable sources of funds going into SRHR through health sector support.Citation13 At one time, 67 countries had PRSPs but more recently some countries have merged these with their national plans and rebranded them.Footnote*

The Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) were launched in 2000. It was not until 2007 and only in part b. of MDG5 was any component of sexual and reproductive health and rights apart from reducing maternal mortality and unmet need for family planning mentioned – the worthy but vague target of universal access to reproductive health, and only because of intense advocacy. A report prepared for the Hewlett Foundation documented that hostility towards legitimizing SRHR within the MDGs stemmed not just from the Bush Administration but also from several developing country governments.Citation14

Then, going against the trend of more holistic funding, new freestanding vertical initiatives were put into place and well-resourced, such as the Global Fund against AIDS, TB and Malaria in 2002. In order to beef up commitment to achieving the health MDGs, a plethora of new “global health initiatives” have emerged, which are also vertical in what they address. It remains unclear how well SRHR will fare. If history is any guide, complacency would not be a wise strategy. For example, the International Health Partnership+ (IHP+) began in 2007 with the goal of improving the way that donors and developing countries work together to support entire health strategies. Many donors and countries have signed on, but it is not clear how it is being made operational nor how transformative it will prove to be. A recent review of the first three years of the IHP+ has documented slow progress and a lack of a common set of indicators.Citation15

Alongside these vertical initiatives, to underscore their commitment to country-led approaches to development cooperation, the nations of the world held two high-level meetings on aid effectiveness, in Paris in 2005Citation16 and Accra in 2008.Citation17 The major elements of the agreements made at these meetings that are relevant to sexual and reproductive health and rights, and which the SRHR community has a vested interest in supporting, were:

| • | Alignment: donor support should be based on national development plans. | ||||

| • | Harmonization: all donors should use common procedures, management systems and shared analysis of performance. | ||||

| • | Country systems to deliver aid should be used, rather than setting up parallel mechanisms. | ||||

| • | Conditionalities on aid should be based on country priorities and not donor objectives. | ||||

These two agreements are taken very seriously by the like-minded donors. Unfortunately, they suffer from three major design flaws that have adversely affected SRHR ODA. The first is that country ownership in developing countries usually proves to be government-only (or mainly) ownership. An insufficient role is given to civil society input in determining health priorities, which therefore do not truly represent national aspirations. Indeed, many of those interviewed for the seven country studies expressed concern that because the civil society voice is non-existent or weak, SRHR is usually not given priority. This point was noted over and over again. Civil society is highly diverse across the SRHR ideological spectrum, and they are usually at the forefront of SRHR progress. However, in almost all of the seven countries, the donors acknowledged that they were making larger grants to a smaller number of NGOs. They and other interviewees expressed concern about the continued viability of smaller but vital SRHR NGOs in both North and South, given this reality.

In contrast, the remit of the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, TB and Malaria (Global Fund) – to meaningfully engage civil society along with governments – provides valuable examples for health ODA in general. This point was also made by many of the respondents.

The second is that practical and appropriate SRHR goals and metrics are lacking, especially in sensitive areas such as safe abortion and access to services for unmarried adolescents. In addition, accountability for impact is focused around achievement of the MDGs. However, although SRHR is partially represented in MDG5, the outcome measures are far from sufficient, let alone optimal, and are often excluded from health sector support agreements anyway. Analysis of performance is therefore often moot, in terms of holding governments and donors accountable for improving sexual and reproductive health.

The third is that the use of country systems to deliver aid will only work if there is strong government commitment to ensuring adequate supplies, health personnel and quality of SRHR services. A recent USAID report measuring contraceptive availability in 36 countries, however, documented frequent stock-outs of many methods, even at the national level. This implies an even more serious picture at district facilities. For some methods, such as emergency contraception, most countries did not report any information at all.Citation18

These are some of the reasons why the strong national commitment to sexual and reproductive health and rights, shared by the public of the like-minded donors, whose countries themselves have some of the best policies on these matters in the world, does not translate into sufficient ODA resources going to this sector in developing countries.

Other structural problems also negatively affect the impact of SRHR ODA effectiveness of the like-minded. For example, these donors value empowering their local embassy staff. This makes sense in theory; after all, embassy staff are on the scene and charged with knowing about the country in which they are stationed. However, the extent of SRHR expertise at the embassies of the like-minded varies a great deal. Some have strong in-house SRHR skills but for others, staff tend to be generalist foreign service officers with no particular SRHR expertise, who usually don't stay more than a very few years in a country before they are reassigned. Thus, in some cases, there is a disconnect between the priority given to SRHR by headquarters staff and the reality at the embassy level, which is documented in the country reports.

The culture of the like-minded includes respect for and deference to multilateral agencies, including the UN bodies, which makes them very reticent about getting too specific with regard to influencing how these agencies allocate their funds. The studies documented that donor staff are highly reluctant even to express an opinion or make a suggestion about resource allocation to these international agencies. Yet since these donors provide a great deal of unrestricted funding to them, they could encourage greater attention to SRHR; many of the respondents felt that not doing so meant that important opportunities were being lost.

All the like-minded donors were said to have a strong commitment to measuring and documenting “impact”, such that their taxpayers can perceive value for money. This is leading to changes that are beginning to show. For example, during the interviews some representatives of the donor agencies mentioned that there is or is likely to be a move away from general budget support (for which impact measures are extremely difficult) towards more project-like modalities – back to the future, if you will, and somewhat in contradiction to Paris and Accra.

The studies reveal that there is a good opportunity for the like-minded donors to translate their commitment to SRHR into meaningful and helpful measures of impact. For example, while there are a huge number of indicators that could be used to track progress, it is rare to find good outcome measures for all major elements of SRHR in any health sector support programme, especially for sub-Saharan Africa. When they do exist, these measures tend to be at such a high level, e.g. changes in contraceptive prevalence or reductions in maternal mortality, that it is not possible to relate results to donor investments in the sector. Good outcome measures for “softer” areas such as advocacy are even harder to come by. Changes in laws and policies resulting from advocacy efforts usually involve many actors and tend to take a long period of time. It is thus particularly difficult to attribute a donor investment or the actions of any particular organization at one time point to a policy or law change at another. Nevertheless, institutions involved in advocacy, and these are mostly NGOs, should be required to identify objective metrics for which they are willing to be held accountable.

A recent DFID evaluation of the SWAp in Malawi, for example, showed that an array of good indicators were included but not of the more controversial elements of SRHR, such as unsafe abortion or meeting the contraceptive needs of sexually active unmarried people.Citation19 Because of the incentive to show progress towards achieving the MDGs, most indicators proposed for health sector support tend to be the most easily measured, such as numbers of vaccinations. SRHR gets short shrift and all too often what really counts isn't counted. If the donors were to negotiate good SRHR outcome measures with developing country governments as part of their support to health sectors, the situation would be much improved.

The UNFPA and WHO have developed a short list of indicators for reproductive health,Citation20 which include total fertility rate, contraceptive prevalence rates, and several indicators for maternal health such as the number of facilities with functioning basic obstetric care and HIV levels among pregnant women. Hospital admissions related to abortion are also included. A review of the indicators used in health sector support in MalawiCitation19 showed that these indicators were focused on reducing maternal mortality and included antenatal care, HIV-positive women receiving antiretrovirals, and pregnant women receiving insecticide-treated bed nets. There were also indicators for contraceptive prevalence rates, the percentage of sexually active people using condoms at the last high-risk sex event and the percentage of young people aged 15–24 correctly identifying ways to prevent the sexual transmission of HIV. Similar maternal and family planning indicators were used in Ghana and Bangladesh health system support.Citation21Citation22

Thus, there is an important opportunity, built on this base, for the like-minded European donors to negotiate with governments to push the envelope and include other critical and more sensitive SRHR indicators such as safe abortions, contraceptive services to unmarried youth, and perhaps even a reduction in gender-based violence. A great deal of work remains to link changes in all of these indicators with the investments of donors and action by governments. The health field, including SRHR, lacks solid impact assessments which document the interventions that have the greatest impact and are the most cost-effective.

Different time horizons are absolutely essential here. Some areas of progress are so basic that progress needs to be made quickly. For example, contraceptive stockouts and lack of availability of trained personnel at service delivery sites are so critical to SRHR goals that immediate action is called for along with good baseline measures to track progress regularly, in order to hold donors and governments accountable. Important lessons from other sectors exist that could be applied to SRHR. For example, cell phone technology is being used in Tanzania to hold the government accountable for improving the water supply at the local level,Citation23 while in Uganda, “naming and shaming” was used in newspaper reports regarding the poor allocation of education funds.Citation24

How do the like-minded programme their SRHR ODA and how much money do they provide?Footnote*

Funds for SRHR from the like-minded donors could be given to the following:

| • | general budget and health sector in countries, | ||||

| • | international agencies, | ||||

| • | global health partnerships, and | ||||

| • | SRHR NGOs in both the North and South | ||||

It is impossible to know how much money each of these donors provides to SRHR, let alone the level of support for the different components of the agenda of the ICPD Programme of Action, for the following reasons. First, countries report on their aid outlays according to the coding used by the Development Assistance Committee of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). These categories combine HIV/AIDS with reproductive health and while it is possible to disaggregate these figures, there remain questions about how accurate the coding is for the different categories,Footnote† as they do not otherwise provide a breakdown of the components of SRHR.

Second, support given to health sectors at the country level does not track the proportion of funds going to SRHR in total and certainly not by ICPD category.

Third, allocations to major multilateral organizations and large national or international NGOs which could or do use funds for SRHR, either do not provide information on expenditures for SRHR at all or not in ways that could be disaggregated according to which donors they came from. Nor, for most of the countries studied, was it possible to obtain from the donors a list of all the SRHR NGOs they funded.

Lastly, neither the resource tracking supported by UNFPA and undertaken by the Netherlands Interdisciplinary Demographic Institute (Resource Flows project), nor the OECD data capture the complexity of what is still called “population funding” going through General Budget Support or SWAps.

Perhaps the best indication of current investments is the level of support given to SRHR international NGOs such as International Planned Parenthood Federation or Marie Stopes International, as well as contributions to the UN Population Fund (UNFPA). Another clue is given by the level of support to health sectors in developing countries and to global health multilateral organizations and NGOs, for whom it is reasonable to assume that some of their resources might go to SRHR.

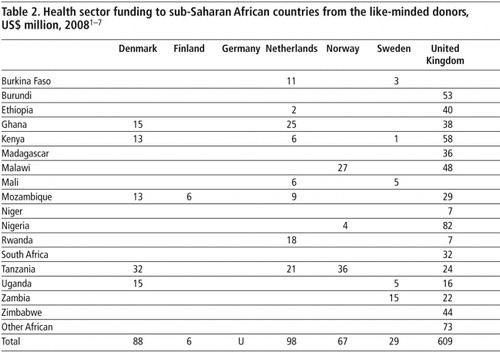

Table 1 Citation25

The table shows that as compared to the amount of funds going to global health organizations and agencies, the portion going to SRHR-focused organizations is relatively modest. Particularly large contributions go to other multilateral sources, especially the Global Fund and UNICEF. If the like-minded were willing to actively encourage these entities to do more in SRHR, they might do so. However, until the like-minded donors strongly advocate with the agencies to play a stronger SRHR role, we will not know if this is a winning strategy or not (nothing ventured, nothing gained).

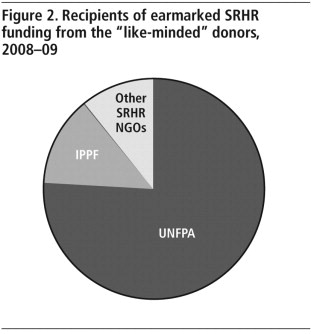

Of funds directly supporting SRHR work, UNFPA is by far the major recipient, while IPPF receives more than all other SRHR NGOs combined.

graphically portrays the relative contributions, based on the data in Table 1.WHO has several departments devoted to SRHR work (Reproductive health and research, Maternal/infant/child/adolescent health, and STIs/HIV/AIDS) but their financial data are extremely confusing, and it was impossible to reach any conclusions about how much of their total support goes to specific departments' work.

The vital position of UNFPA

With about 80% of the funds earmarked by the like-minded donors for SRHR channelled through UNFPA to both their headquarters and country offices, the Fund has a vitally important role in setting priorities for the field and in establishing and reinforcing good policies and practices. The recent leadership change at UNFPA coincided with two major assessments of its performance: DFID's multilateral aid review,Citation26 and the Center for Global Development's Working Group report on UNFPA's Leadership Transition.Citation27 Both reports made similar recommendations for improving the Fund's effectiveness and impact, namely:

| • | Focus on the core priorities of SRH and reproductive rights and resist the temptation of mission creep, | ||||

| • | Increase transparency about how decisions are made, resources allocated and performance measured, | ||||

| • | Recruit, train and retain staff appropriate for these functions, and | ||||

| • | Clearly differentiate its role in improving SRH and reproductive rights vis-á-vis other multilateral agencies. | ||||

The success UNFPA has in implementing these recommendations will be an important overall determinant of the effectiveness of the SRHR ODA investments of the like-minded donors.

Distribution of aid to African countries

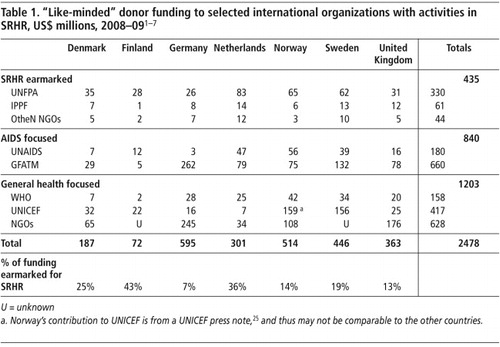

shows the distribution of aid by the like-minded donors to various target countries.Footnote* In terms of support to national health sectors in sub-Saharan Africa, some countries, notably Germany, were not able to provide comprehensive information about the amount of funds they provide; however, they have identified health as a priority in Cameroon, Kenya, Malawi, Rwanda, South Africa and Tanzania and are interested in improving health in many other sub-Saharan African countries, which is not reflected in the table. This is true to some extent of Norway, too. From the five reports that did include more comprehensive country-level data, the key findings are:| • | Sub-Saharan Africa is the region of focus for all the like-minded donors. DFID data, for example, indicate that for 2009–10 most of their health sector aid went to Africa (56%) (although DFID in particular is also active in Asia, where 42% of their health sector budget was distributed in 2009–10).Citation28 | ||||

| • | Some sub-Saharan African countries such as Kenya, Mozambique and Tanzania, receive health sector support from several of the like-minded. | ||||

| • | The amounts of money are generally far smaller than the resources provided to the multilateral agencies. | ||||

Donor agencies were questioned about how they made decisions regarding which developing countries to work in. In the like-minded countries whose ODA is channelled through a development agency, it is usually the Ministry of Foreign Affairs that makes the decision. For those where the ODA function has ministerial status, decisions are made by those ministries based on a variety of historical, political and need factors. In addition, consideration is given to human rights and corruption. However, the studies did not reveal any standardized or objective way that these governments determine which developing countries receive health ODA from them and which do not.

Conclusion and recommendations

Because the like-minded donors are so important for SRHR – indeed they are really the only donors willing to embrace the entire ICPD package – improving their impact at the field level for the world's most vulnerable women, especially in sub-Saharan Africa, is critical and it has become clear that there is a substantial opportunity to improve the tangible outcomes of their good intentions. The evidence amassed in this study points to four immediate recommendations to increase the impact and effectiveness of their SRHR ODA at the country level:

| • | Assign a much stronger role to civil society in the design and implementation of health sector support programmes. This is consistent with the spirit of the Paris and Accra accords and with the values of the like-minded donors. Making it happen will likely require reinforcing the SRHR knowledge and negotiating skills of embassy staff in some of the like-minded donor embassies so that they can be more effective advocates for this change. In the developing countries where these donors no longer have embassies, SRHR knowledge and advocacy skills will need to be provided from other sources. For reinforcement of the role of civil society to be successful, the like-minded donors may also need to get a bit out of their comfort zone in negotiating with those governments who may be disinclined to accept this change or pay it only lip service. | ||||

| • | Support a thorough analysis of how to strengthen SRHR civil society, so that they can be a full partner in development. As part of this analysis, consider setting up a special independent fund to strengthen SRHR civil society to keep this sector alive and healthy,Footnote* so that it can be more strategic and effective in this expanded role. In the world's poorest countries, civil society is itself chronically starved for funding and often managerially weak. To date, Southern NGOs and their Northern sister organizations have worked well together to advocate for more effective SRHR policies and to test out innovative approaches. Unfortunately, most of the like-minded donors are cutting off funding to these Northern organizations since they are under pressure from senior government leaders to become more “efficient” by making fewer grants to larger entities. This is leaving a large hole in the existing SRHR ODA architecture. If these Northern NGOs go out of business, the survival of their Southern partners is in further jeopardy. | ||||

| • | In partnership with WHO, UNFPA and developing countries, donors should get agreement on a set of SRHR outcome measures that will be taken seriously and used in the evaluation of health sector ODA. New technologies, such as cell phones, texting and social networking would enable some valuable baseline data to be collected in a quick and efficient way, from which progress can be assessed, for example, for addressing stockouts of basic commodities. Donors and governments could utilize cell phones to monitor the situation in all but the most remote clinics. Information could be updated and sent to an appropriate organization (usually non-governmental) for analysis. Once these steps have been completed both donors and governments would have a timely and vital base from which to set performance goals and monitor and manage progress toward them. There are many other ways of approaching this important issue but it requires the like-minded, NGOs and Southern governments to be more actively and forcefully involved than they currently are. | ||||

| • | Work with UNFPA to implement the recommendations of the DFID multilateral review and the Center for Global Development's working group report on the UNFPA Leadership Transition. In recognition of the difficult and sensitive mandate of UNFPA, many of the like-minded are reluctant to insist on transparency, even about how it allocates and expends resources. These reports documented a very mixed record of the like-minded working with UNFPA constructively in order to help them focus and to identify the right metrics for the assessment of their performance. With almost 80% of the earmarked SRHR funds of the like-minded going to UNFPA, this is a high priority. | ||||

Thoughts for the future

Together, the seven like-minded donors form the core of progressive support for SRHR ODA. Despite internal political changes within these countries, to date their commitment to women's sexual and reproductive health and rights has remained firm. Each of the seven has points of great strength in the ways in which their SRHR funding is programmed. Each also could do more to improve the impact of their SRHR investments. Happily, the studies indicate practical actions that these donors could take that would result in improving access of the world's most vulnerable women to the sexual and reproductive health services that they need and want. Based on these studies, I would recommend these donors to insist on meaningful civil society representation during negotiations for health ODA (the Global Fund shows that this can be done) and, critically, to be willing to invest in the capacity building and infrastructure to make this succeed. I would ask them to build on the work that all of them have done to develop and agree on more comprehensive indicators through which the impact of health ODA can be monitored to ensure that core SRHR metrics are included. Some of this is already happening but much more can be done, especially around the more sensitive areas of unsafe abortion, providing services to sexually active young people, and protections against gender-based and sexual violence. The studies indicate that investments in the capacity to collect data on these topics would be money well spent for SRHR. I would also ask them to move out of their comfort zone and be more forthright with the multilateral agencies that they fund so generously, to provide incentives for them to do more in SRHR and to allocate more of their resources to areas of greatest need, such as Francophone sub-Saharan Africa. Finally, I would ask them to realize that they personally are extremely important advocates for SRHR and in that regard they should ensure that they themselves and their colleagues within their agencies are fully prepared to take on this role.

Acknowledgements

This article would not have been possible without the excellent analyses of the European donor development cooperation for sexual and reproductive health prepared by Birte Holm Sørensen (Denmark), Riikka Shemeikka (Finland), Catherina Hinz and Matthias Wein (Germany), Frans Baneke and Wouter Meijer (Netherlands), Berit Austveg (Norway), Sarah Thomsen (Sweden), and David Daniels and Rolla Khadduri (UK). Paul Rosenberg of the Hewlett Foundation and Rolla Khadduri of Mannion Daniels provided excellent research assistance. The author is particularly grateful for the insightful comments and writing suggestions of Paul Clermont.

Notes

* The UK Department for International Development (DFID) recently undertook a major review of the impact of its investments in the multilateral organizations. DFID has stated that it will use this assessment to guide future funding. If it does and the other like-minded follow suit, then it may signal more active oversight in the future.

* It is not the purpose of this paper to evaluate whether these mechanisms have proven successful. but rather to provide a brief context to the ODA approaches of the like-minded.

† A lot has been written, especially by the World Bank, about the impact and effectiveness of supporting entire health systems, some of which is of particular relevance for SRHR. Citation8–10

* Board presentations, PRSP documents, World Bank, 2 June 2010.

* All of the financial information in this section comes from the seven country reports. The researchers used published data as well as more recent information provided by their donor agencies. Citation1–7

† The commonly quoted example is that a condom project can be coded under HIV/AIDS or under family planning, but not under both.

* Because the studies intentionally focused on Africa, aid to countries in other regions, many of which have rapidly been defunded, having reached what is called middle-income status (no matter what their SRHR status is) was not raised in the interviews.

* This notion is certainly not confined to SRHR. It is hard to envision an area in which the effectiveness of ODA would not be greatly improved by broadening the base of country ownership to include material participation by civil society.

References

- B Austveg. ODA for SRHR (Norway), 2011. At: <www.dsw-online.org/odastudies. >.

- F Baneke, W Meijer. ODA for SRHR (Netherlands), 2011. At: <www.dsw-online.org/odastudies. >.

- D Daniels, R Khadduri. ODA for SRHR (UK), 2011. At: <www.dsw-online.org/odastudies. >.

- C Hinz. ODA for SRHR (Germany), 2011. At: <www.dsw-online.org/odastudies. >.

- BH Sørensen. ODA for SRHR (Denmark), 2011. At: <www.dsw-online.org/odastudies. >.

- R Shemeikka. ODA for SRHR (Finland), 2011. At: <www.dsw-online.org/odastudies. >.

- S Thomsen. ODA for SRHR (Sweden), 2011. At: <www.dsw-online.org/odastudies. >.

- V Walford. Defining and evaluating SWAps: a paper for the Inter-Agency Group on SWAps and Development Cooperation. 2003; Institute for Health Sector Development HLSP: London.

- V Walford. A review of health sector wide approaches in Africa. July. 2007; Institute for Health Sector Development HLSP (for DFID): London.

- D Vaillancourt. Do health sector-wide approaches achieve results? Emerging evidence and lessons from six countries (Bangladesh, Ghana, Kyrgyz Republic, Malawi, Nepal, Tanzania). Independent Evaluation Group Working Paper 2009/4. 2009; World Bank: Washington, DC.

- C Chansa. Zambia's Health SWAps Revisited. 14 August. 2009; Lambert Academic Publishing.

- UN International Conference on Population and Development Programme of Action. At: <www.iisd.ca/Cairo/program/p00000.html>. Accessed 5 June 2011.

- World Bank. A Review of Population, Reproductive Health and Adolescent Health and Development in Poverty Reduction Strategies. 2004; World Bank: Washington, DC.

- B Crosette. Reproductive health and the Millennium Development Goals: the missing link. At: <www.hewlett.org/uploads/files/ReproductiveHealthandMDGs.pdf. >. Accessed 5 June 2011.

- R Labonte, A Marriott. IHP+: little progress in accountability or just little progress?. Lancet. 375: 2010; 1505–1507.

- High Level Forum. Paris Declaration on Aid Effectiveness, 2 March 2005. At: <www.oecd.org/dataoecd/11/41/34428351.pdf. >.

- High Level Forum on Aid Effectiveness. Accra Agenda for Action, 4 September 2008. At: <www.oecd.org/dataoecd/11/41/34428351.pdf. >.

- USAID Deliver Project. Measuring contraceptive security indicators in 36 countries. USAID Deliver Project Task Order 1. April 2010.

- M Pearson. Impact evaluation of the SWAp, Malawi. Final Report. 2010; DFID Human Development Resource Centre: London.

- UNFPA WHO. Building UNFPA/WHO capacity to work with National Health and Development Planning Processes in Support of Reproductive Health. Report of a Technical Consultation. Geneva, 2005. At: <www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/health_systems/rhr_06_02/en/index.html. >. Accessed 7 June 2011.

- Birungi H, Nyarko P, Askew I, et al. Priority setting for Reproductive Health at the District Level in the Context of Health Sector Reforms in Ghana. Population Council; Ministry of Health in Ghana; UNFPA/Ghana; Ghana Health Service. April 2006.

- Martinez J. Sector wide approaches at critical times: the case of Bangladesh. HLSP Institute, Technical approach paper; February 2008.

- Anneryan Heatwole. Maji Matone: using mobiles for local accountability (and flowing water). 15 June 2011. At: <www.mobileactive.org/maji-matone-water-monitoring. >.

- R Reinikka, J Svensson. Fighting corruption to improve schooling: evidence from a newspaper campaign in Uganda. Journal of European Economic Association. 3(2–3): 2005; 259–267.

- UNICEF press note. Unicef.org/media_46865.html. 17 December 2008.

- Department for International Development, UK. Multilateral aid review: ensuring maximum value for money for UK aid through multilateral organisations. March. 2011; DFID: London.

- Center for Global Development. Focus UNFPA: Four Recommendations for Action. Report of the CGD Working Group on UNFPA's Leadership Transition. 2011; CGD.

- Department for International Development, UK. Statistics for International Development 2010. 2011; DFID: London.