Abstract

A social franchise in health is a network of for-profit private health practitioners linked through contracts to provide socially beneficial services under a common brand. The early 21st century has seen considerable donor enthusiasm for promoting social franchises for the provision of reproductive health services. Based on a compendium of descriptive information on 45 clinical social franchises, located in 27 countries of Africa, Asia and Latin America, this paper examines their contribution to universal access to comprehensive reproductive health services. It finds that these franchises have not widened the range of reproductive health services, but have mainly focused on contraceptive services, and to a lesser extent, maternal health care and abortion. In many instances, coverage had not been extended to new areas. Measures taken to ensure sustainability ran counter to the objective of access for low-income groups. In almost two-thirds of the franchises, the full cost of all services had to be paid out of pocket and was unaffordable for low-income women. While standards and protocols for quality assurance were in place in all franchises, evidence on adherence to these was limited. Informal interviews with patients indicated satisfaction with services. However, factors such as difficulties in recruiting franchisees and significant attrition, franchisees' inability to attend training programmes, use of lay health workers to deliver services without support or supervision, and logistical problems with applying quality assurance tools, all raise concerns. The contribution of social franchises to universal access to reproductive health services appears to be uncertain. Continued investment in them for the provision of reproductive health services does not appear to be justified until and unless further evidence of their value is forthcoming.

Resumé

Dans la santé, une franchise sociale est un réseau de praticiens privés à but lucratif tenus par contrat d'assurer des services socialement bénéfiques sous une même marque. Au début du XXIe siècle, les donateurs ont encouragé avec beaucoup d'enthousiasme les franchises sociales pour les services de santé génésique. Se fondant sur un recueil d'informations descriptives relatives à 45 franchises sociales cliniques, situées dans 27 pays d'Afrique, d'Asie et d'Amérique latine, cet article examine leur contribution à l'accès universel à des services globaux de santé génésique. Il révèle que ces franchises n'ont pas élargi l'éventail de services de santé génésique, mais se sont principalement centrées sur la contraception et, dans une moindre mesure, les soins maternels et l'avortement. Dans de nombreux cas, la couverture n'avait pas été étendue à de nouvelles zones. Les mesures prises pour garantir la viabilité vont à l'encontre de l'objectif d'accès des groupes à faible revenu. Dans près des deux tiers des franchises, le coût total de l'ensemble des services devait être payé par les patients et était inabordable pour les femmes à faible revenu. Les normes et les protocoles d'assurance qualité étaient en place dans toutes les franchises, mais on dispose de données limitées sur leur observance. Des entretiens informels avec des patients ont indiqué qu'ils étaient satisfaits des services. Néanmoins, les difficultés pour recruter des franchisés et une certaine usure, l'incapacité des franchisés de suivre des programmes de formation, l'utilisation d'agents de santé profanes pour assurer des services sans soutien ni supervision et des problèmes logistiques pour appliquer les outils d'assurance qualité sont autant de facteurs préoccupants. La contribution des franchises sociales à l'accès universel aux services de santé génésique paraît incertaine. Il ne semble pas justifié de continuer d'investir en leur faveur pour la prestation de services de santé génésique, à moins que de nouvelles données ne prouvent leur utilité.

Resumen

Una franquicia social en salud es una red de profesionales de la salud particulares con fines de lucro, vinculados mediante contratos para ofrecer servicios de beneficio social bajo una marca en común. A principios del siglo XXI se ha visto un considerable entusiasmo por parte de donantes para promover las franquicias sociales para la prestación de servicios de salud reproductiva. Basado en un compendio de información descriptiva sobre 45 franquicias sociales clínicas, situadas en 27 países de Ãfrica, Asia y Latinoamérica, este artículo examina su contribución al acceso universal a los servicios integrales de salud reproductiva. Se encontró que estas franquicias no han ampliado la gama de servicios de salud reproductiva, sino que se han centrado principalmente en servicios de anticoncepción y, a menor grado, en servicios de salud materna y de aborto. En muchos casos, no se había extendido la cobertura a nuevas áreas. Las medidas tomadas para garantizar sostenibilidad eran contrarias al objetivo de acceso para grupos de bajos ingresos. En casi dos terceras partes de las franquicias, las pacientes tuvieron que pagar el costo total de todos los servicios, inasequible para mujeres de bajos ingresos. Aunque todas las franquicias habían establecido normas y protocolos para garantizar la calidad, había limitada evidencia de su cumplimiento. Las entrevistas informales con pacientes indicaron satisfacción con los servicios. No obstante, preocupan factores como las dificultades en reclutar franquiciados y una considerable amortización de puestos de trabajo, la imposibilidad de los franquiciados de asistir a programas de capacitación, el uso de trabajadores de la salud laicos para proporcionar servicios sin apoyo o supervisión, y los problemas logísticos aplicando las herramientas de garantía de la calidad. La contribución de franquicias sociales al acceso universal a los servicios de salud reproductiva parece ser incierta. A menos que surja más evidencia de su valor, no se justifica continuar invirtiendo en ellas para la prestación de servicios de salud reproductiva.

Privatisation of health services may be defined as “a broad range of policies and mechanisms adopted by governments and donors that wish to alter the public/private mix in favour of the latter”.Citation1 The privatisation-versus-state involvement debate is at least a century old. Some of the ideas of those in favour of the private sector date back to 300–400 years of economic thinking that considers the “market”, through its competitive mechanisms, as capable of protecting the interests of the consumer far better than any government mechanism.

The 1990s Thatcher–Reagan era witnessed growing support for limiting the role of the state and increasing the role of the private sector in all sectors of the economy, including social services. Perhaps a sign of the time in which it came into existence, the Programme of Action of the International Conference on Population and Development (ICPD) in 1994, as part of its strategy for achieving universal access to reproductive health services by 2015, explicitly supported a greater role for the private sector in the provision of reproductive health services. For example, it recommended:

“To strengthen the partnership between governments, international organisations and the private sector in identifying new areas of co-operation; and

To promote the role of the private sector in service delivery and in the production and distribution, within each region of the world, of high-quality reproductive health and family planning commodities and contraceptives, which are accessible and affordable to low-income sectors of the population.” (Para.15.5)Citation2

Today, various forms of privatisation are being pursued in the provision of reproductive health services, predominantly in Asia and Africa, but also in Latin America. Governments have engaged in contracting of services – contracting both in and out – often with the non-profit sector in their countries as the provider.Citation4–7 In addition, a number of innovative interventions have been introduced by donors to promote the private sector role in reproductive health services. These include social marketing of contraceptives, safe delivery kits and other reproductive health commodities, and social franchising networks involving for-profit private health providers.Citation8 Interventions such as Banking on Health by USAID work with private health care businesses and facilitate their access to finance. USAID has also designed the Development Credit Authority, which covers up to 50% of defaults on loans made by private financial institutions to private health care businesses. The project is reported to have worked in 12 countries during 2004–2009.Citation9 A 2010 publication of the project reported that Banking on Health assistance had helped private health care businesses receive more than US$192 million in financing in nine countries in Africa and Latin America.Citation10

Social franchising initiatives

A commercial franchise may be defined as:

“a form of business organization in which a firm which already has a successful product or service (the franchiser) enters into a continuing contractual relationship with other businesses (franchisees) operating under the franchiser's trade name and usually with the franchiser's guidance, in exchange for a fee.” Citation11

A social franchise in health services is a variant of the commercial franchise. According to the Global Health Group (2010), a social franchise “encompasses a network of private health practitioners linked through contracts to provide socially beneficial services under a common brand”. The outlets are owner-operated and the services are standardised.Citation13

Franchises may be “stand-alone” or “fractional”. In stand-alone franchises, the franchiser provides infrastructure and equipment to the franchisee service provider, who provides the franchised products and services exclusively. In fractional franchises, new services – typically contraceptive services – are added to the basket of services already being provided by an existing service provider.Citation14 Social franchises that provide health services requiring a nurse or a higher level health provider in an OECD country have in recent terminology been classified as “clinical social franchises”.Citation13

Social franchises may have as franchisees multiple categories of health providers operating at different levels. For example, a social franchise may consist of a network of community health workers, clinics offering outpatient services and hospitals offering inpatient services. Some social franchises also include laboratories and pharmacies. Franchisers in a social franchise are typically international or national not-for-profit organisations which receive donor funding for setting up a social franchise initiative.Citation15 A new development in 2007 was the “government social franchise” model in Viet Nam, where provincial health departments in two provinces networked and branded selected public clinics under their jurisdiction.Citation13

A social franchise is characterised by a number of core features. There is a model or prototype which is replicated in several locations; a manual that sets out the concept and all the processes; a brand name for the franchise; a contract governing the relationship between the franchiser and franchisee; standardised training for franchisees; and systematic and standardised methods of monitoring and quality control.Citation16

The franchisee pays a franchise fee and in return for membership gets access to commodities, supplies and equipment at reduced cost. S/he also receives training in clinical and business skills, and benefits from advertisement of the franchise “brand” which his/her facility is identified by. The franchisees' obligations include following standards of quality and clinical protocols and maintaining records and reporting regularly to the franchiser.Citation15

The Blue Circle network launched in 1988 in Indonesia with funding support from USAID was the first social franchising arrangement. The franchiser was the Badan Koordinasi Keluarga Berencana Nasional (National Family Planning Co-ordinating Board, BKKBN), and franchisees included general practitioners and midwives. Blue Circle aimed to shift urban clientele for family planning from middle and lower socio-economic groups to the private sector. Starting out with four major cities in 1988, the Blue Circle programme rapidly expanded to cover 300 cities by its third year and was launched nationally in 1990.Citation17 In 1994, the Sangini social franchise was launched in Nepal, followed by Greenstar in Pakistan in 1995.Citation18

While there were only about ten social franchises until 2003, at least ten more came into existence during 2004–2007 and 22 new clinical social franchises were started during 2008–2011.Citation13

Several factors seem to have contributed to the emergence and rapid expansion of social franchises for provision of reproductive health services. One, social marketing programmes distributing oral contraceptive pills and condoms through commercial marketing outlets found it necessary to enter into arrangements with private clinicians in order to distribute products such as the intrauterine device, which required clinical training. Two, funding for reproductive health services by international donors as well as governments continued to decline and this led to calls for effective partnerships with the private sector.Citation19 Three, networks of private providers were attractive to international donors because of the large numbers of providers who could be drawn in to rapidly expand the supply of health services.Citation15 Social franchising networks also appeared to offer economies of scale in training, capacity building, procurement and distribution of products and advertising.Citation19

According to the Global Health Group, a social franchise has four primary social goals:

| • | Access: increasing the number of service delivery points and providers, as well as the range of services offered; | ||||

| • | Cost-effectiveness: providing services at an equal or lower cost to other service delivery options, inclusive of all subsidy and system costs; | ||||

| • | Quality: providing services that adhere to quality standards and improve pre-existing standards of quality; and | ||||

| • | Equity: serving all population groups, emphasizing those most in need.Citation20 | ||||

These goals are also mentioned by other proponents of social franchising arrangements for reproductive health services In addition, they suggest that social franchises have the potential to contribute to health equity by shifting users who can pay to social franchises, thereby freeing up the public sector for use by those most in need;Citation21Citation22 offer the possibility of sustainable provision of priority reproductive health services; and as an effective model of partnership with the private sector, respond to the MDG5 target of universal access to reproductive health services by 2015.Citation19

Evidence of the extent to which social franchises have contributed to the goals of access, equity, quality and sustainability is limited. Many of the existing evaluations have concerned themselves with client volume and client satisfaction. For example, baseline (2004) and impact (2006) evaluations of social franchises in Ethiopia, India and Pakistan showed: a) that franchise membership increased client volume, and b) a greater proportion of clients receiving reproductive health services in franchised clinics expressed satisfaction as compared to those receiving such services in non-franchised clinics. Franchise membership also significantly influenced the number of reproductive health services offered.Citation23Citation24

An evaluation using a quasi-experimental study design in Nepal similarly found that a greater proportion of clients of franchised clinics were satisfied and willing to return to the clinic despite higher costs. However, there was no significant difference between control and intervention districts in use of family planning.Citation25 In Nicaragua, an evaluation using a similar study design found that women using franchised clinics reported a higher level of satisfaction with franchised as compared to non-franchised clinics. Socially franchised clinics catered to a niche of users whose income levels were higher than those using public facilities but lower than those using private facilities. Women living closer to a franchised clinic also reported better health status than did women in the control group.Citation26

A 2011 systematic review of social franchises in reproductive health analysed 12 studies – three systematic reviews and nine primary studies.Citation27 Seven of the 12 studies addressed aspects of coverage. Social franchising was found not to be related to any increase in client volumes across settings. Five studies examined quality of care and found mixed results regarding whether patient perception of quality of care was better in social franchised health facilities, although in one post-intervention survey patients described the health provider as having a “caring manner”. Of six studies which looked at changes in health and health behaviour outcomes, three showed an increase in knowledge and use of family planning methods among franchise clients. However, there were mixed results about franchised clinics' ability to reach young, poor and illiterate clients across settings, and the location of clinics in low-income urban areas did not guarantee that their clientele were low-income. The review concluded that:

“Despite the enthusiasm within the donor community and serious attention within the literature, no rigorous evidence existed as to the effect of social franchising on access to and quality of health services in low- and middle-income countries.” Citation27

| • | To what extent have social franchising initiatives increased the range of reproductive health services and population coverage by these services? | ||||

| • | What is their contribution to removing financial barriers to accessing reproductive health services by poor and marginalised sections of the population? | ||||

| • | What is the quality of services provided in socially franchised health facilities? | ||||

Methodology

A compendium of social franchising programmes in developing countries published by the Global Health Group at the University of California, San Francisco, USA, forms the principal source of data for the analysis carried out in this paper. The compendium, produced first in 2009 and updated annually since, covers almost all social franchises currently operationalFootnote* and is the only source of comparable data on a wide range of characteristics of social franchises. The latest edition of the compendium, published in 2011, documents information on 50 clinical social franchises.Citation13

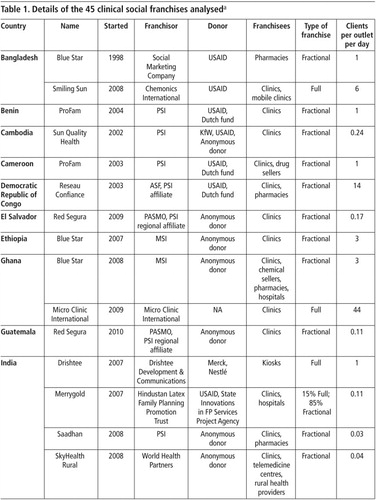

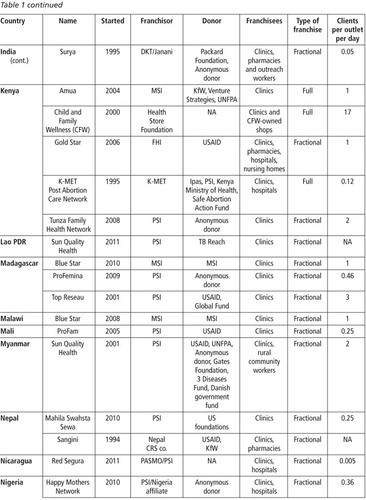

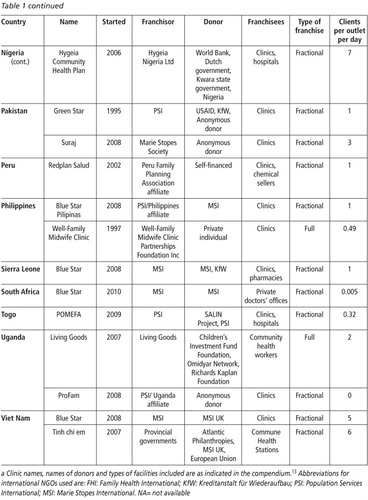

Forty-five clinical social franchises form the sample used for analysis below (Table 1

). Three social franchises which provided HIV-related services only, one social franchise which only distributed reproductive health commodities and one which did not provide reproductive health services were excluded from the analysis. Quantitative data available from the compendium have been supplemented with detailed qualitative information from case studies of ten of the 45 social franchises: Amua Kenya, Blue Star Ethiopia, Blue Star Ghana, Blue Star Pilipinas, Blue Star Viet Nam, Merrygold India, Smiling Sun Bangladesh, Sun Quality Health Myanmar, Suraj Pakistan, and Tunza Kenya.Citation28–37Data on services and products provided by social franchises available from the compendium are used to address the question on increased availability, and data on couple years of protection and average number of clients served per outlet are used to assess extent of population coverage. Data on franchisees' target clientele and sources of payment for services, together with descriptive information on efforts made by the franchises to address inability to pay are used as indicators of affordability and equitable access for low-income groups. Information on quality control measures and challenges in ensuring quality, in combination with data on the level of training of providers running the clinics, are used as indicators of quality of care.

Findings

Characteristics of social franchises

The 45 clinical social franchises reviewed are located in 27 countries of Africa, Asia and Latin America. Fifteen of the 45 are located in East and Southern Africa, 11 in South Asia, eight in West Africa, seven in Southeast Asia and four in Latin America. However, in terms of population served, South Asia has 78% of the total clients, Southeast Asia 9%, East and Southern Africa 7%, West Africa 4% and Latin America 2%.Citation13

Twenty-seven of the 45 franchisers are international NGOs while eight are local affiliates of international NGOs. Local private enterprises are franchisers in nine instances, one of which has joint ownership with an international NGO. There are two instances where the government is involved in social franchising. In the Amua network in Kenya, the Government of Kenya receives funding from an external donor and has engaged Marie Stopes Kenya to implement the network on its behalf. The Tinh chi em (Sisterhood) franchise in Viet Nam is a fully government-run social franchise; the provincial department of health is the franchiser and financial support is provided by an external donor.Citation13

In 41 of the 45 social franchises, franchisees are outlets or enterprises operated by for-profit health service providers. In one instance, Smiling Sun Bangladesh, franchisees are clinics run by 27 not-for-profit organisations, funded by USAID and brought together under one umbrella through a donor initiative. In the government social franchise in Viet Nam, franchisees are all public clinics (commune health stations), while a small proportion of clinics in the ProFam franchise in Benin and the Hygeia franchise in Nigeria are public sector facilities. Community health workers or outreach/marketing workers are an integral part of 37 of the 45 franchises.Citation13

While 25 of the 45 franchises include clinics only, 17 also include different levels of health care facilities, pharmacies and chemist shops. One franchise is a network exclusively of pharmacies, while two franchises are networks exclusively of community health workers who operate in the community.Citation13

Thirty-eight of the 45 social franchises are fully externally funded. This includes three franchises – two in Kenya and one in Bangladesh – whichreceive free contraceptive supplies from the Government. Two social franchises receive some funding from local or national governments, although predominantly supported by external donors. One social franchise is self-financed and one is supported by a private individual, while there is no information on three.Citation13

Eleven of the externally funded social franchises are supported by a single anonymous donor. USAID is the only donor in six and one of the major donors in seven of the 45. Marie Stopes International either alone or with other donors supports seven social franchises, while Kreditanstalt für Wiederaufbau (KfW), the German government development bank, supports six franchises. Other donors include the Dutch government, UNFPA, World Bank, and Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, each providing support to one or two social franchises.Citation13

The majority of social franchises (36/45) are fractional franchises, that is, a limited range of franchised services have been added to the basket of services of an already existing clinic. Eight of the 45 are full franchises, while one includes both full franchisees and fractional franchisees. The majority (28/45) provide only reproductive health services, while 17 also provide services for one or more of the following conditions: diarrhoea, malaria, paediatric diseases, tuberculosis.Citation13

Range of services provided

The full range of reproductive health care services as envisaged in the ICPD Programme of Action includes:

| • | Family planning services; counselling; and information, education and communication (IEC) services; | ||||

| • | Services and IEC for antenatal care, safe delivery and post-partum care; | ||||

| • | Prevention and treatment of infertility; | ||||

| • | Safe abortion services in accordance with the ICPD Programme of Action,Footnote* and management of complications arising from unsafe abortions; | ||||

| • | Treatment of reproductive tract infections, sexually transmitted infections and other reproductive health conditions; and | ||||

| • | IEC and counselling as appropriate on human sexuality, reproductive health and responsible parenthood.Citation22 | ||||

Have social franchises contributed to making an increased range of reproductive health services available? It would appear that social franchises may be making existing services available more widely rather than making new services available. Of the 42 social franchises for which this information was available, 39 provide contraceptive services and 16 provide abortion-related care. Twelve franchises each provide maternal health care and screening and treatment for STIs, respectively, and six franchises provide cervical cancer screening.Citation13

Many of the social franchises strive to provide a wide choice of contraceptive methods. For example, 22 of 39 networks provide a choice of five or more modern methods. Emergency contraception is available through ten franchises. The availability of male and female sterilisation is constrained by the limited skills level of providers; only seven franchises offer these methods in a small proportion of their franchised facilities.Citation13

As regards maternal health care, offered in 12 franchises, four offer emergency obstetric care in a small proportion of outlets that are equipped for such services, while six franchises, including these four, also attend normal deliveries. The others provide only antenatal and postnatal care, while one franchise merely distributes supplies of misoprostol to pregnant women to prevent post-partum haemorrhage.Citation13

Both medical and surgical abortion are provided in seven of the 16 franchises providing any abortion-related care. Three provide only medical abortions and one provides only surgical abortion, while only post-abortion care is included in the standard package of the remaining five franchises. However, even when abortion is said to be part of the standard package of franchised services, local sensitivities may dissuade franchisees from providing it. This is reported to be the case for Blue Star, Ghana, a franchise of midwives. After an increase in the numbers of abortions provided immediately after the induction training, the numbers fell again owing to negative public response.Citation30

Coverage

One of the major arguments in favour of social franchises in reproductive health is that they could extend coverage of much-needed reproductive health services to those who were hitherto underserved.

In the case of fractional franchises (36/45) no new clinics have been set up in places where they did not exist before.Citation13 To the extent that community outreach workers have been newly deployed, and for clinic users who did not get reproductive health services before, coverage is likely to have increased. In a number of instances, however, franchised clinics mention competition from “free” government services, other franchises and private providers. For example, franchised clinics of Blue Star in Ethiopia were located in three of the most populous areas with the maximum number of private clinics.Citation29 This is not surprising. When clinics recruited into the franchise are already in business, they are likely to be located in areas with an assured market for their services, and this is where other private providers are also likely to operate. Amua and Tunza franchises in Kenya,Citation28Citation37 Blue Star in Ethiopia and Viet Nam,Citation29Citation32 and Merrygold franchise in IndiaCitation33 reported competition from government clinics that provide free contraceptive services. This suggests that, at least in some instances, franchises operate in areas already covered by services.

In the compendium, the performance of clinical social franchises is measured mainly in terms of couple years of protection (CYPs) of contraception.Footnote* Three of the social franchises: Blue Star Bangladesh, Greenstar Pakistan, and Well-Family Midwife Clinic in the Philippines, all three of which have a large number of outlets across multiple tiers and a few thousand community outreach workers, have achieved impressive coverage of more than 2 million CYPs each.Citation13 However, the coverage achieved by the others is not very high. In 18 of the 36 franchises for which data are available, the CYPs achieved per outlet was less than 260 for the year 2010, and all but the top three achieved a coverage of less than 1300 CYPs per outlet.Footnote† It is also not clear whether these represent additional CYPs or a switch from another provider to the concerned franchise, and therefore, whether coverage has increased overall.Citation13

Data on the average number of service users for 2010 (available for 42/45 franchises) also indicate a relatively modest level of coverage (see Table 1). Seventeen of 42 franchises reported an average client load of one or less than one per day. Calculated from data in the compendium, the maximum average number of users per outlet per day of 44 was recorded by Child and Family Wellness Foundation in Kenya, and included users of shops and pharmacies among their outlets.Citation13

Out-of-pocket fees for services and equity

Data on mode of client payment are available for 43 of 45 social franchises. Out-of-pocket payment was the dominant mode (90% of all clients) of payment in 36 of the 43 franchises, including 27 in which it was the only mode of payment. In the remaining nine, a small proportion of clients were covered by vouchers schemes, private or government insurance and direct subsidies, either by the franchiser or by the government.Citation13

Social franchises where out-of-pocket payment was the sole source of payment included 19 that reported specifically targeting low-income groups. Clients' inability to pay for services features as one of the problems reported by social franchises in the compendium.Citation13 For example, the Ghana Blue Star franchise recommends a charge of US$25–40 for abortion services, while the average earnings of a woman from the franchise's baseline survey was found to be approximately US$33 per month.Citation30 In many of the Amua clinics in Kenya, “one in four women arrived without any money in their pockets”.Citation28 A study of the Merrygold franchise in Uttar Pradesh, India, found that utilisation of their clinics by low-income groups was significantly lower than utilisation by relatively better-off groups. According to a clinic manager of the network:

“The basic problem is that they simply cannot afford the services.” Citation33

Franchisee efforts to achieve sustainability by cutting subsidies and increasing prices may make matters worse. For example, in Tunza, Kenya, IUDs were initially provided free of cost to the client. Later, clients were required to pay 50% of the cost for the device (400 Kenyan shillings or US$5). Starting in 2010, clients have had to pay the full cost of 800 Kenyan shillings.Citation37 In Bangladesh, Smiling Sun increased prices by 60% during 2008–2011 as part of its effort to recover at least 50% of running costs.Citation34

In nine franchises, where clinics have tied up with national health insurance schemes and government voucher or subsidy schemes, free services have been provided to 25–75% of clients. When free services are provided, this could be either that specific contraceptives are provided free, or that a certain group of clients are provided all services free of cost. For example, sterilisation is provided free of cost to all clients in the Surya franchise in India and in the Smiling Sun franchise in Bangladesh, in both instances only in clinics accredited by the government and reimbursed for providing these services.Citation13 As yet, the numbers of clinics within the franchises providing such free services appears to be low, but efforts to get accreditation for more clinics would be beneficial to low-income clients.

Smiling Sun in Bangladesh has set up a “poorest of the poor” fund to subsidise the cost of services to low-income clients. Community outreach workers identify the poor based on specific indicators and issue a green card to women from such households. Services and products in Smiling Sun clinics are provided free of cost to those producing the green card.Citation34

Vouchers are used to subsidise specific services in some franchises, with the cost difference paid by the franchiser. Community health workers of the Suraj franchise in Pakistan distribute vouchers for IUDs to eligible women from poor households. Identification of the poor is done on the basis of nine self-reported indicators. Women who produce the voucher need not pay for IUD insertion in Suraj clinics.Citation36 Not only the poor but all eligible community members are given vouchers for IUDs and for STI services by Sun Quality Health in Myanmar. Voucher holders receive IUD insertion services and STI diagnosis and treatment services at subsidised costs of US$0.50 and US$0.25, respectively.Citation35 Responding to lack of demand for IUDs because of the high cost of the device, Blue Star Viet Nam introduced a voucher scheme that entitled voucher holders to free IUD insertion and removal services; service providers were reimbursed by the franchiser.Citation32

There are also government-subsidised voucher schemes. For example, six franchisees in the Amua programme in Kenya were registered under the Government of Kenya's Output-Based Aid voucher scheme. Government community health workers sold family planning and safe motherhood vouchers to women at highly subsidised rates, and women could exchange these in the six clinics for free services.Citation28 Ten franchisee clinics in the Smiling Sun network, Bangladesh, were registered with a government voucher scheme for maternal health services. The voucher covered a standard maternal and child health care package, caesarean sections and transportation costs up to 750 Bangladeshi takas (US$10).Citation34

Hygeia in Nigeria stands apart as an example of a community-based insurance scheme with a network of collaborating health facilities. All clients of this franchise are covered by the Hygeia Community Health Plan for maternal and child health care services at the primary and secondary level.Citation13

Formal mechanisms for subsidising low-income clients apart, all franchisees reported informal waivers and subsidies for those expressing the inability to pay.Citation13 However, informal mechanisms cannot and should not replace formal policy to remove financial barriers to reproductive health services. Women needing services may not be aware that they can be obtained at low or no cost from a franchised clinic and may be reluctant to ask for waivers or subsidies. For example, in a Suraj clinic in Pakistan:

“One client wanted an injectable. She inquired about the cost (Pakistani Rs.70) and left before I was able to inform her about the sliding scale. The woman then tried to save up enough money to pay for the injectable but by the time she was able to do so, she was already pregnant.” Citation36

Quality of care: staffing and quality assurance measures

While a majority of the franchises (27/45) have at least one physician in their clinical outlets, 12 are staffed only by nurses, midwives or clinical assistants, and four have some but not all clinics run by non-physicians. Two franchises are run exclusively by community-level workers and 35 franchises have a network of community outreach workers for marketing of the brand, who recruit and refer clients to the clinic. Workers at the community level also provide some health services such as health education, distribution of non-clinical methods of contraception and other health commodities.Citation13

Some of the case studies report difficulties in recruiting and retaining physicians and midwives. For example, Amua and Tunza networks in KenyaCitation28Citation37 reported that medical doctors were not interested in becoming franchisees. “Most doctors had a patronising attitude to Tunza services”.Citation37 In Viet Nam, the government required Blue Star clinics to be led by an obstetrician-gynaecologist, but these doctors were not particularly interested in joining the franchise because they already had enough clients and had no time to attend training programmes. Only a third of the doctors contacted by the franchiser joined the franchise.Citation32 In Blue Star Ethiopia, only 37% of franchisees recruited in the pilot phase continued into the scale-up phase,Citation29 and in Sun Quality Health, Myanmar, 17–20% of doctors recruited left the franchise within the pilot phase.Citation35 Recruitment of midwives by Blue Star Pilipinas was no easy task either, with only 5% of midwives contacted by the franchiser completing requirements to become a franchisee.Citation31

All ten case studies of clinical social franchises list a number of steps that the franchises take to assure quality of care. These include rigorous selection criteria, high-quality training of franchisees, regular monitoring visits, mystery-client studies to review quality of services and prices charged, and use of Quality Technical Assistance (QTA) tools to monitor technical quality of care through direct observations.Citation13 Details of the outcome of these measures are available for some franchises.

Smiling Sun in Bangladesh, for example, reported conducting 6,000 deliveries with only one maternal death, recording a maternal mortality ratio far below the national average of 340 per 100,000.Citation39 The QTA assessments carried out once in six months in Blue Star Viet Nam found that a majority scored over 70%,Citation32 while franchisees of Tunza, Kenya, had an average score of above 80% based on the quality checklist they regularly filled in.Citation37

All case studies which included informal client interviews reported that clients were satisfied with the services and had chosen the clinic because of lower cost of services as compared to other private facilities and consistent good quality.Citation28–37 Other factors mentioned included doctors' caring and respectful behaviourCitation32Citation35Citation36 and flexible hours.Citation36

Enforcing quality in franchisee outlets was fraught with problems, however, according to accounts from some of the franchises. Amua Kenya and Blue Star EthiopiaCitation28Citation29 could not always complete the training as planned, because fractional franchisees were not willing to take time off from providing services. This also meant that training programmes necessarily had to be of short duration. Squaring this with the need to provide skills training, e.g. in manual vacuum aspiration for abortion or IUD insertion, would indeed be difficult to achieve. The high turnover of personnel employed in some of the franchises means that some of the providers in franchisee clinics may not have received the required training till the next training cycle.

Regular monitoring visits were also reported to be difficult to accomplish in franchises where the outlets are scattered over a wide area. Amua Kenya, Blue Star Ethiopia and Blue Star GhanaCitation28–30 had great difficulty in organising Quality Technical Assurance visits to carry out direct observation of procedures because of the low client load for IUDs and other clinical procedures. Franchisers in Ethiopia, Ghana and KenyaCitation28–30,37 reported that even when poor quality of care was identified, they chose not to take action against the franchisee; according to one, this was because “disincentives are counterproductive to maintain a relationship of mutual respect”.Citation30 Taking action against those who do not meet quality standards may therefore be difficult also in other settings where franchisees are difficult to recruit and retain.

There are other quality concerns as well. The range of contraceptive choices available is an indicator of quality of care in family planning. On one hand, most social franchises make at least five contraceptive methods available, thus increasing contraceptive choice. On the other hand, case studies of some of the clinical franchises mention reluctance on the part of franchisees to provide contraceptive methods that are time consuming or do not result in monetary returns. For example, franchisees of Sun Quality Health in Myanmar felt that IUDs had a low profit margin and took a long time to insert because of the need to sterilise the equipment. The franchiser, Population Services International, raised donor funding to pay US$4.50 to the providers, to make up the difference between what they expected to be paid (US$5) and what the client could afford to pay ($0.50).Citation35 Such incentives may be difficult to sustain over a long period of time. Providers in the Amua network of Kenya did not want to refer patients for tubal ligation because this involved considerable counselling time, for which no revenue was generated.Citation28 In some instances, new contraceptives were added to the menu because of their profitability. The Suraj network was planning to introduce hormonal implants among the range of contraceptives offered because they are a “high cost and low volume” product which could increase franchisee profitability.Citation36

Another issue relates to the use in some of the franchises of outreach workers with just a few days' training, to carry out not only health education and social mobilisation but services that call for a high order of skills, often without regular medical supervision or guidance. For example, the Living Goods franchise in Uganda, which consists exclusively of women community health promoters, provided among other things, pregnancy care, family planning and referrals.Citation13 Sun Primary Health, the second tier of Sun Quality Health in Myanmar, is a network of auxiliary nurse midwives (36%), community health workers (24%), farmers (18%) and members of other occupations (21%). A case study of this franchise mentions plans to provide misoprostol to these providers as part of a post-partum haemorrhage health kit.Citation35 The wisdom of using lay workers with limited training for pregnancy and delivery care and family planning, in the absence of linkages to higher levels of care, is questionable.

There are only a small number of evaluation studies of social franchising arrangements available in the public domain. Two studies of the Green Star and Key Marketing Services franchises in Pakistan found infection control to be seriously compromised,Citation6 and poor infection control practices are mentioned as a challenge by many of the 45 clinical social franchises discussed here.Citation13

Conclusions

The analysis in this paper of descriptive information about 45 social franchises on the potential of social franchises to contribute significantly to universal access to reproductive health services, raises more questions than it provides answers.

Social franchises have in general not added much to the range of reproductive health services, but have focused largely on making contraceptive services more widely available. Most social franchises make at least five contraceptive methods available, thus increasing contraceptive choice. However, data on distribution of users across different methods would have made it possible to assess whether women could actually exercise contraceptive choice or whether barriers such as stock-outs and provider biases reported from some franchises prevented this, and to what extent.

Social franchises have clearly not been the answer to non-availability of services in rural and hard-to-reach areas. A majority of the franchises involved clinics that were already operational, and hence have not contributed to a better geographic distribution of facilities. Coverage by reproductive health services may have increased for populations in the catchment areas of the clinics, but data on couple years of protection achieved by franchises are not adequate to know whether more couples are actually using a method or have merely switched from another provider to the franchise. The average number of clients serviced by individual clinics is relatively modest: about two-thirds of the franchises served only one client or less per day.

Although more than 80% of the franchises explicitly mention low-income groups as their target population, out-of-pocket expenditure remains the dominant mode of payment in the vast majority of social franchises. Efforts have been made to subsidise clients in several franchises, but the proportion receiving waivers and subsidies remain insignificant in 36 of the 45 franchises examined. In nine franchises, where clinics have tied up with national health insurance schemes and government voucher or subsidy schemes, free services have been provided to 25–75% of clients. These need to be studied further to examine their replicability in other settings.

Quality of care measures form an integral part of all 45 social franchises, but there is scarce evidence on whether these are enforced. Factors such as difficulties in recruiting franchisees and significant attrition among those recruited, franchisees' inability or unwillingness to attend training programmes, the widespread use of health workers with limited training to deliver health services, the absence of adequate support and supervision mechanisms and logistical problems related to implementing Quality Technical Assistance tools, raise concerns about adherence to quality in socially franchised clinics. This is especially so in settings where general levels of quality in health facilities – public or private – are not satisfactory, and hence, there are no role models to emulate.

The report of a WHO meeting on sexual and reproductive health franchises held in 2007 highlighted problems of sustainability faced by sexual and reproductive health franchises. The report observed that such franchises are compelled to include services which are more lucrative to allow for cross-subsidising of those that are highly price-elastic, such as contraceptive services. Seventeen of the 45 reproductive health social franchises in this paper have indeed included curative care for a number of communicable diseases among services offered. The WHO report points out that there are trade-offs between serving the poor, providing a full range of sexual and reproductive health services and financial sustainability,Citation19 and our findings indicate the same.

The WHO report called for more evidence to be gathered on the cost-effectiveness of social franchises in reproductive health services as compared to other modes of investing the funds,Citation19 yet 22 of the franchises studied in this paper have appeared since 2008, in the absence of such evidence (Table 1). This seems curious in an era of clamour for evidence-based policy and programmes on the part of donors, multilateral agencies and policy makers.

The world is currently faced with a funding shortage of US$24 billion for advancing the ICPD agenda of universal access to reproductive health services.Citation40 There is no justification for investing in the creation of more social franchising networks until some crucial questions are answered on the merits of social franchising as a pathway to universal access to reproductive health services. These include:

| • | Do the services that will be provided by the social franchise concerned add to the range of services called for by the ICPD Programme of Action and substantially increase the number of people in receipt of services, e.g. achieving higher contraceptive prevalence and reducing unmet need, and therefore merit the investment and the risk? | ||||

| • | Can the social franchise provide these services at least as cost-effectively as by alternative investment of these funds, including in the public sector? | ||||

| • | Is there evidence to show that any social franchise under consideration will increase equitable access to reproductive health services for low-income and marginalised populations?Citation41 | ||||

Continued investment in social franchises for the provision of reproductive health services does not appear to be justified until and unless the answers to these questions – and further evidence of their value – are forthcoming.

Notes

* The compendium excludes social franchises that do not provide clinical services and are not owner-operated. There are at least five other clinical reproductive health social franchises not included in the compendium but mentioned in the literature – one in SE Asia, two in East Africa and two in Latin America. This paper does not cover these.

* “In circumstances where abortion is not against the law, such abortion should be safe” (Para.8.25).

* Couple years of protection are calculated as the number of contraceptives distributed within a programme in one year, by type, multiplied by the average length of time they are effective.

† In order to get some sense of how the extent of coverage compares with couple years of protection achieved in other programmes, we compared the CYPs per outlet with a benchmark of 260 CYPs, achieved by a single health provider in a year from a report on performance of a community-based family planning programme in Zimbabwe.Citation38

References

- TKS Ravindran. Public-private interactions. TKS Ravindran, H de Pinho. The Right Reforms? Health sector reform and sexual and reproductive health. 2005; School of Public Health, University of Witwatersrand: Johannesburg.

- United Nations. Population and Development, Programme of Action adopted at the International Conference on Population and Development, Cairo, 5–13 September 1994. A/CONF.171/13/Rev.1. 1994; UN: New York.

- R Berg. Initiating public/private partnerships to finance reproductive health: the role of market segmentation analysis. May. 2000; USAID Policy Working Paper Series: Washington DC.

- Asian Development Bank. Report and recommendation of the President to the Board of Directors on a proposed loan to the Kingdom of Cambodia for the Health Sector Support Project. 2002; Asian Development Bank: Manila.

- World Bank. Partnering with NGOs to strengthen management: an external evaluation of the Chief Minister's Initiative on Primary Health Care in Rahim Yar Khan District, Punjab. 2006; World Bank, South Asia Human Development Sector: Washington DC.

- TKS Ravindran. Privatisation in reproductive health services in Pakistan: three case studies. Reproductive Health Matters. 18(36): 2010; 13–24.

- TKS Ravindran. Pathways to universal access to reproductive health care in Asia. Reclaiming and redefining rights. Thematic Studies Series 2. 2011; Asian Regional Resource and Research Centre for Women (ARROW): Kuala Lumpur.

- C Skaar. Extending coverage of priority health services through collaboration with the private sector: selected experiences of USAID Cooperating Agencies. 1998; Abt Associates Inc, Partnerships for Health Reform: Bethesda MD.

- Banking on Health Project. At: <www.abtassociates.com/page.cfm?PageID=1686&FamilyID=1600&OWID=2109768040&CSB=1>. Accessed 30 August 2011.

- Banking on Health Project; and Development Credit Authority Guarantee. At: <www.bankingonhealth.com>. Accessed 9 May 2010.

- What is a franchise? Definition and meaning. At: <www.investorwords.com/2078/franchise.html>. Accessed 25 August 2011.

- What is a franchise? Definition of franchise. At: <http://franchises.about.com/od/franchisebasics/a/what-franchises.htm>. Accessed 25 August 2011.

- K Schlein, H Kinlaw, D Montagu. Clinical Social Franchising Compendium: An Annual Survey of Programs, 2011. 2011; Global Health Group, Global Health Sciences, University of California, San Francisco: San Francisco.

- J McBride, R Ahmed. Social franchising as a strategy for expanding access to reproductive health services: a case study of Green Star delivery network in Pakistan. Community Marketing Strategies Technical Paper. 2001; Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu: Washington DC.

- T Chandani, S Sulzbach. Private provider network: the role of viability in expanding the supply of reproductive health and family planning services. 2006; Private Sector Partnerships-One Project, Abt Associates Inc: Bethesda MD.

- J Meuter. Social franchising. At: <www.berlin-institu.org/online-handbookdemography/social-franchising.html. >. Accessed 20 August 2011.

- LS Mize, B Robey. A 35-year commitment to family planning in Indonesia: BKKBN and USAID's historic partnership. 2006; Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School for Public Health, Centre for Communications Program: Baltimore.

- History of social franchising. At: <www.sf4health.org/socialfranchises/history-social-franchising>. Accessed 25 August 2011.

- World Health Organization. Public policy and franchising reproductive health: current evidence and future directions. 2007; WHO: Geneva.

- Social franchises definition. At: <www.sf4health.org/socialfranchises/definition>. Accessed 25 August 2011.

- Provider networks: increasing access and quality care. Commercial Marketing Strategies, New Directions in Reproductive Health. At: <www.cmsproject.com>. Accessed 30 April 2010.

- UN Population Fund. Implementing the reproductive health vision. Progress and future challenges for UNFPA. August. 1999; UNFPA: New York.

- R Stephenson, A Tsui, S Sulzbach. Franchising reproductive health services. Health Services Research. 39(6 Pt 2): 2004; 2053–2080.

- A Tsui, A Creanga, Y Myint. The impact of franchising reproductive health services on client service use in Ethiopia, India and Pakistan. 2006; Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School for Public Health: Baltimore. (Unpublished report).

- S Agha, A Karim, A Balal. A quasi-experimental study to assess the performance of a reproductive health franchise in Nepal. 2004; Commercial Market Strategies Project: Washington DC.

- S Sulzback. Evaluation of a CMS private clinic network in Nicaragua. 2003; USAID: Washington DC. As quoted in: Chandani T, Sulzbach S. Private provider network: the role of viability in expanding the supply of reproductive health and family planning services. Bethesda, MD: Private Sector Partnerships-One Project, Abt Associates Inc, 2006.

- T Koehlmoos, R Gazi, S Hossain. Social franchising evaluations: a scoping review. 2011; Social Science Research Unit, Institute of Education, University of London: London.

- Marie Stopes International. MSI Clinical social franchising case study series. Amua Network; Marie Stopes Kenya. 2010; MSI: Nairobi.

- Marie Stopes International. MSI Clinical social franchising case study series. Blue Star Healthcare Network, Marie Stopes International Ethiopia. 2010; MSI: Nairobi.

- D Montagu, H Kinshaw. Clinical social franchising case study series. Blue Star Ghana; Marie Stopes International. 2010; Global Health Group, Global Health Science, University of California at San Francisco: San Francisco.

- VL Pernito, RC Deiparine, FJT Francisco. Clinical social franchising case study series. Blue Star Pilipinas, Marie Stopes International. 2010; Global Health Group, Global Health Science, University of California at San Francisco: San Francisco.

- Marie Stopes International. MSI Clinical social franchising case study series. Blue Star Healthcare Network, Marie Stopes International Vietnam. 2010; MSI: Nairobi.

- EC Blanco. Franchising mechanisms in Uttar Pradesh, India: working for the poor people? Equity and quality aspects. 2010; Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine, MPH Dissertation: Liverpool.

- K Schlein, H Kinlaw. Clinical social franchising case study series. Smiling Sun Franchise Program Bangladesh/Chemonics International. 2011; Global Health Group, Global Health Science, University of California at San Francisco: San Francisco.

- K Schlein, K Drasser, D Montagu. Clinical social franchising case study series. Sun Quality Health/PSI Myanmar. 2010; Global Health Group, Global Health Science, University of California at San Francisco: San Francisco.

- R Saeed, F Kerai Khan. Case study: ‘Suraj’: a private provider partnership. 2010; Marie Stopes Society Pakistan: Karachi.

- Global Health Group. Clinical Social Franchising case study series. Tunza Family Health Network/PSI Kenya. 2010; Global Health Group, Global Health Science, University of California at San Francisco: San Francisco.

- Zimbabwe National Family Planning Council. An assessment of the Zimbabwe National Family Planning Council's Community-Based Distribution Programme. 2001; ZNFPC; Population Council; Family Health International: Harare.

- World Health Organization. Trends in maternal mortality: 1990–2008. Estimates developed by WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA and the World Bank. 2010; WHO: Geneva.

- US Agency for International Development. Social franchising in health services: a Philippines case study and review of experience. 2003; USAID: Washington DC.

- United Nations Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC). Boost funding for integrated sexual, reproductive health services, Population Fund Chief urges as Commission on Population and Development opens session. 11 April 2011. At: <www.un.org/News/Press/docs/2011/pop991.doc.htm. >. Accessed 30 August 2011.