Abstract

Although Shanghai has good maternal health indicators, it also has a large in-migrating population, which has made control of maternal mortality a major challenge. This study analyzed maternal mortality and causes of death in pregnant women in Shanghai in the ten years from 2000 to 2009, comparing resident and migrant women. All live births were registered and every maternal death audited. The number of live births rose from 84,898 in 2000 to 187,335 in 2009. The number of migrants increased 4.6 times, while the proportion of live births to migrant women increased from 27% to 55%. There were 262 maternal deaths, 55 in Shanghai residents and 207 in migrant women (78.9% of the total). Most deaths in migrant women were due to illegal delivery. Three policy changes focusing on maternal health greatly reduced deaths: low-cost delivery services were established for migrant women in maternity hospitals, five obstetric emergency care and referral centres were created in general hospitals, and training for health professionals and health education for women were instituted. Maternal mortality in Shanghai decreased steadily from 2000 to 2009, reaching 10 per 100,000 live births in 2009. Among Shanghai permanent residents the ratio was below ten in most of those years, while among migrant women it declined sharply from 58 to 12 per 100,000 live births.

Résumé

Bien que Shanghai possède de bons indicateurs de santé maternelle, la ville abrite aussi une vaste population immigrante, et la lutte contre la mortalité maternelle y représente donc un enjeu majeur. Cette étude a analysé la mortalité maternelle et les causes de décès chez les femmes enceintes à Shanghai pendant 10 ans, de 2000 à 2009, en comparant les résidentes et les migrantes. Toutes les naissances vivantes ont été enregistrées et chaque décès maternel a été examiné. Le nombre de naissances vivantes est passé de 84 898 en 2000 à 187 335 en 2009. Le nombre de migrants a augmenté de 4,6 fois, alors que la proportion de naissances vivantes chez les migrantes passait de 27% à 55%. On a enregistré 262 décès maternels, 55 résidentes de Shanghai et 207 migrantes (78,9% du total). La plupart des décès de migrantes étaient dus à des accouchements clandestins. Trois changements politiques centrés sur ont sensiblement réduit la mortalité : l'établissement de services obstétricaux à faible coût pour les migrantes dans les maternités, la création de cinq centres de soins obstétricaux d'urgence et de référence dans les hôpitaux généraux, et l'institution d'une formation des professionnels de santé et de l'éducation sanitaire des femmes. La mortalité maternelle à Shanghai a diminué régulièrement depuis 2000, atteignant un taux de 10 pour 100 000 naissances vivantes en 2009. Parmi les résidentes permanentes de Shanghai, le taux était inférieur à dix pendant la plupart de ces années, alors que chez les migrantes, il a reculé rapidement de 58 à 12 pour 100 000 naissances vivantes.

Resumen

Aunque en Shanghái existen buenos indicadores de salud materna, también hay un gran número de inmigrantes, por lo cual es muy difícil controlar la mortalidad materna. En este estudio se analizó la mortalidad materna y las causas de muerte de mujeres embarazadas en Shanghái durante un plazo de diez años, del 2000 al 2009, y se compararon las mujeres residentes con migrantes. Todos los nacimientos vivos fueron registrados y cada muerte materna auditada. El número de nacimientos vivos aumentó de 84,898 en 2000 a 187,335 en 2009. El número de migrantes aumentó 4.6 veces, mientras que la proporción de nacimientos vivos a mujeres migrantes aumentó del 27% al 55%. Hubo 262 muertes maternas, 55 entre residentes de Shanghái y 207 entre mujeres migrantes (78.9% del total). La mayoría de las muertes entre mujeres migrantes fueron causadas por partos ilegales. Tres cambios a las políticas centrados en disminuyeron en gran medida las tasas de muertes: se establecieron servicios de bajo costo para mujeres migrantes en maternidades, se crearon cinco centros de cuidados obstétricos de emergencia y referencia en hospitales generales, y se instituyeron programas de capacitación para profesionales de la salud y de educación sobre la salud para las mujeres. Las tasas de mortalidad materna en Shanghái disminuyeron a un ritmo constante entre 2000 y 2009, alcanzando 10 por cada 100,000 nacimientos vivos en 2009. Entre las residentes permanentes de Shanghái la proporción fue menos de diez en la mayoría de esos años, mientras que entre las mujeres migrantes aumentó bruscamente de 58 a 12 por cada 100,000 nacimientos vivos.

Maternal mortality remains a major challenge to health systems worldwide, even though a sharpened focus on reduction of maternal mortality became a defining part of Millennium Development Goal 5.Citation1 However, the reduction in maternal mortality over the past decade has been modest overall, with a yearly rate of decline in the global maternal mortality ratio (MMR) since 1990 of 1.3%.Citation2

To achieve the MDG goal of reducing its 1990 MMR by three-quarters by 2015, China is on track. Between 2000 and 2005, the Chinese vital registration system recorded 64,780,153 live births and 30,672 maternal deaths, resulting in an overall MMR of 47 deaths per 100 000 live births.Citation3 As a metropolitan city, Shanghai has a higher level of maternal health care than most other provinces and the lowest MMR in China.Citation4 In 2000, the MMR of Shanghai permanent residents was below 10 per 100,000 live births, comparable to the level of many developed countries.Citation3,4

Since the 1990s, however, China has experienced major internal population migration, with millions of people moving from central and western China to the east coast and large cities. In Shanghai, the population of 16.4 million in 2000 had increased by 35% in 2010, according to census data. Migrants now account for about 36.4% of Shanghai's population, an increase from 19.4% in 2000.Citation5 The number of live births among the migrant population exceeded that of Shanghai's permanent residents in 2005 and migrant women became the majority maternity population. This has created a great challenge for Shanghai's health system, especially since insurance for maternity care covers fewer than 20% of women in China. Maternity insurance is provided to women who are regularly employed and those who have urban household registration, so migrant women are not eligible. Most migrant women have no regular job or income, and their level of education is also lower than that of Shanghai permanent residents. They are and have been at higher risk for maternal death than Shanghai residents, and indeed, most maternal deaths since 1997 in Shanghai have been among the migrant population. This situation was described up to 2005 in a previous study,Citation4 but it continues to be true today. This paper provides an update of the situation and describes the interventions that have been initiated by the government and the maternity services to reduce the number of deaths, as a result of which MMR in Shanghai has been falling in recent years.

Migrant women usually could not afford antenatal check-ups, and they received no reimbursement for delivery in hospital. Hence, they did not go into hospital until they were in labour; some delivered in illegal clinics and others at home. In order to encourage migrant women to have antenatal check-ups and hospital delivery in 2004 and 2007 the government released two policy documents entitled “Creation of low-cost maternity care in hospitals” and “Enhancement of the management of maternal health in migrant women”.Citation6,7 These established low-cost delivery care for the migrant population in existing maternity hospitals, so that they could have timely antenatal care and hospital delivery for safe childbirth.

Shanghai has 17 counties. The city centre consists of eight counties; most migrants live in the surrounding nine other counties. Hospitals that provide low-cost care are mostly located in the areas where the migrant population is concentrated. Migrant women can receive maternity services at a much lower cost, 150 yuan RMB for antenatal check-ups and 800 yuan RMB for spontaneous delivery, compared to 2000–3000 yuan RMB for antenatal check-ups and 3000–4000 yuan RMB for spontaneous delivery for residents. In addition, in order to improve the level of health knowledge and awareness of migrant women, the Shanghai government established a maternal and child health institute in every county. Every year since the low-cost delivery care was established, community-based maternal and child health workers carry out lecture tours that highlight the availability of low-cost delivery in designated maternity hospitals and the importance of early pregnancy registration, and provide information and education on pregnancy and childbirth.

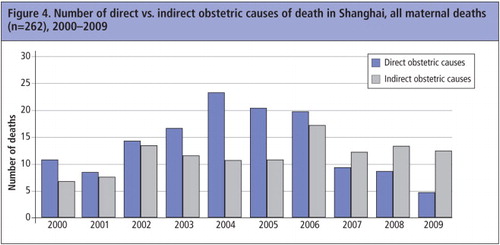

Emergency obstetric care is also important for reducing maternal deaths. Because skilled obstetric care has been developed so fast in Shanghai, the direct causes of maternal death have declined and indirect causes increased proportionally. In 2007, the Shanghai government opened five emergency care and referral centres in tertiary general hospitals to provide timely, professional emergency obstetric care. The referral network covers all maternity hospitals in Shanghai, including those for migrant women, and previous difficulties in referral and consultation, especially for women from rural areas, have been resolved.

The object of the research reported here was to analyze the causes of maternal deaths and the MMR in Shanghai from 2000 to 2009 and summarize the experiences and problems of maternity care management.

Methods

Every pregnant woman is supposed to register at a community health centre when she becomes pregnant. If she does not, community maternal and child health workers will remind or persuade her to do so. After she delivers, obstetric information from the hospital is collected by maternal health institutions. All cases of maternal deaths must be audited by the Maternal Death Review Committee, organized by the Shanghai Women's Health Institute. The Committee consists of experts in maternal and perinatal health from the primary, regional and tertiary levels of maternity care.

This study was carried out in Shanghai from 2000 to 2009. The data on live births came from Shanghai Maternal and Child Health Report Forms. All relevant documents, including medical charts, expert audit documents, and Shanghai Maternal and Child Health Report Forms, were assembled for reviewing. Final diagnosis of each maternal death was made by consensus of the committee members. At the end of every year, every case of maternal death was checked with the Public Security Bureau and Centre for Disease Control and Prevention to ensure that every case had been audited. If any maternal deaths were missed, an audit of the case would be held.

The definition of maternal death used was the International Classification of Diseases 1992 definition: the death of a woman while pregnant or within 42 days of pregnancy termination, irrespective of pregnancy duration or method of termination, excluding deaths from intentional and unintentional injuries.Citation8

We analyzed live births and overall MMR in migrant women and permanent residents in Shanghai, and then looked at the causes of maternal deaths and the results of the maternal death audits.

Findings

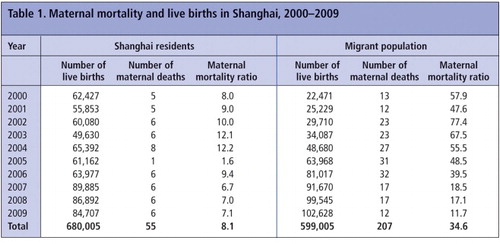

The number of live births in Shanghai rose from 84,898 in 2000 to 187,335 in 2009, an increase of 120%. The number of births rose rapidly from 2004 and had doubled by 2007 compared to 2000, mainly because of the increased number of live births in the migrant population, which rose 4.6 times during the ten years (accounting for 25.5% of the total in 2000 and 54.8% of the total in 2009).

There were 262 maternal deaths in the ten years with an average MMR of 20.5 per 100,000 live births. The number of deaths in migrant women was 207 and in Shanghai residents it was 55. The MMR was 8 per 100,000 live births in Shanghai residents and 35 per 100,000 live births in migrant women. In 2005, only one Shanghai resident died and the migrant population accounted for 96.9% of the total deaths.

MMR declined from 21 per 100,000 live births in 2000 to 10 per 100,000 live births in 2009. Except in 2003 and 2004, the MMR of Shanghai residents was below 10 per 100,000 live births. Among migrant women, MMR declined dramatically from 58 per 100,000 live births in 2000 to 12 per 100,000 live births in 2009, a decrease of 79.8% (Table 1).

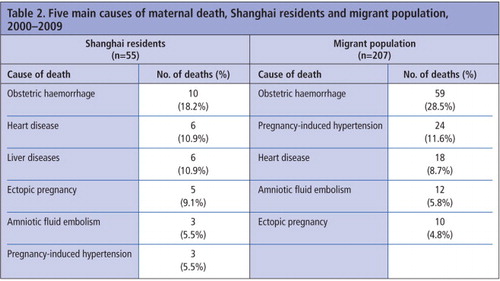

Table 2 shows the five main causes of maternal deaths in Shanghai residents and migrants. Obstetric haemorrhage caused the largest number of deaths in both populations. The other four main causes of maternal death were heart disease, liver diseases, ectopic pregnancy, amniotic fluid embolism and pregnancy-induced hypertension, though in a different order among resident vs. migrant women.

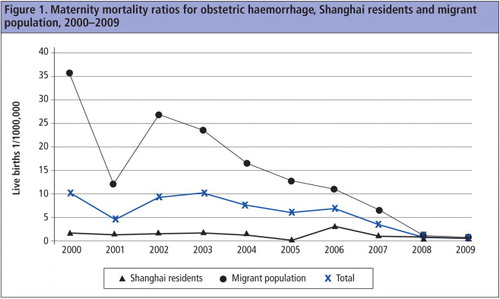

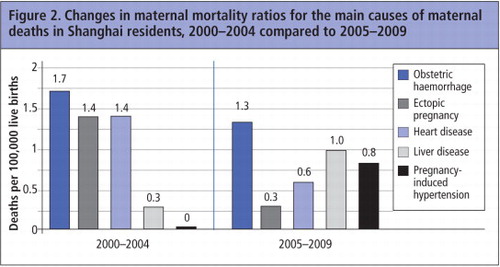

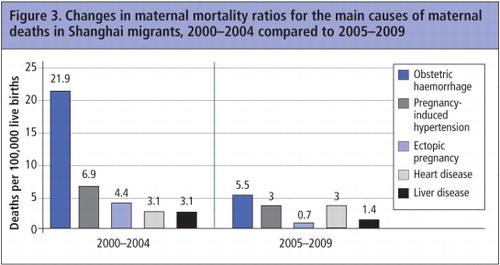

In the years 2000–2004 compared to 2005–2009, the main causes of maternal death changed in both sub-populations. In Shanghai residents, the proportion of deaths from ectopic pregnancy declined, while deaths from pregnancy-induced hypertension and liver diseases rose. In migrants, the proportion of deaths from obstetric haemorrhage, ectopic pregnancy and pregnancy-induced hypertension declined dramatically. Overall, the MMR related to obstetric haemorrhage declined from 22 per 100,000 live births to 5.5 per 100,000 live births (a decline of 74.9%). Especially in the migrant population, MMR related to obstetric haemorrhage declined from 36 per 100,000 live births in 2000 to 1 per 100,000 live births in 2009, a decline of 97.3% (). Ectopic pregnancy declined from 4 per 100,000 to 0.7 per 100,000 (a decline of 84.4%), and pregnancy-induced hypertension from 7 per 100,000 live births to 3 per 100,000 live births (declined by half) ( and ).

Of the total 262 maternal deaths from 2000 to 2009, 141 were due to direct obstetric causes and 121 to indirect obstetric causes. The proportion of indirect causes of death increased each year, from 38.9% in 2000 to 72.2% in 2009 ().

In sum, the MMR in Shanghai decreased steadily over the ten years of the study, and reached 10 per 100,000 live births in 2009, a developed country level.Citation9,10 Among Shanghai permanent residents MMR was below 10 in most of those years, while among migrant women it declined from 58 in 2000 to 12 per 100,000 live births in 2009.

Discussion

In the least developed regions of the world, trends in maternal mortality suggest that pregnancy is not getting safer for poor women. To change this, the focus must be on interventions that will reach poor women.Citation11 In Shanghai, most migrant women are from rural areas of China, have a lower socioeconomic status and are not well educated. Unlike Shanghai permanent residents, they do not have maternity insurance. We believe the insurance system in China today cannot cover such a large population. Without any help, however, some of the poorest women would not be able to afford the cost of antenatal care and delivery in a hospital, which was the main reason why the MMR among migrant women was much higher than that of permanent residents.Citation12 The establishment of low-cost delivery in maternity hospitals for the migrant population contributed’greatly to reducing maternal deaths among them.Citation13 However, this is not a long-term solution. We believe the government should consider covering maternal health insurance for migrant women step by step, which would be an essential resolution of the problem.

Post-partum haemorrhage accounts for nearly one-quarter of maternal deaths worldwide.Citation14 In Shanghai, it was the most common cause of maternal deaths among migrant women.Citation4,15 Most of these deaths were due to illegal delivery. After low-cost delivery services for migrant women in maternity hospitals were established, the rate of delivery of migrant women in hospital increased,Citation16 and mortality from obstetric haemorrhage decreased by 97.3% from 2000 to 2009. This alone made the MMR of migrant women decline by 78.9%.

The construction of emergency care and referral centres for pregnant women was another important measure for reducing maternal deaths due to direct obstetric causes among both resident and migrant women. Emergency obstetric care requires not only the involvement of obstetric departments, but also the collaboration of other departments.Citation17 The decrease in the mortality rate from heart disease and liver disease also showed the effectiveness of these centres.

Finally, strengthening professional training and health education to improve the awareness and capability of obstetricians and physicians, and increasing the awareness and ability of self-help health care among pregnant women were another guarantee of safer motherhood. With ectopic pregnancy, for example, Shanghai Women's Health Institute conducted various trainings and simulated performances to improve the alertness and skills of obstetricians and related physicians to ensure every maternity hospital attaches importance to acute abdominal pain in women and has the ability to deal with it. On the other hand, maternal and child health centres in every county have provided maternal health education to the target population to improve their knowledge and prevent delays in seeking treatment.Citation18 The fall in mortality from ectopic pregnancy in 2005–2009 from 2.4 to only 0.5 per 100,000 live births shows the importance and necessity of professional training for health workers and health education for pregnant women.

Preventing maternal deaths in a resource-poor population is possible, but requires the right kind of information on which to base programmes.Citation19 The analysis of maternal mortality ratios and causes of death can help to find underlying factors and provide evidence for effective interventions. Comprehensive measures, including policies focusing on the target population, health education and obstetric emergency care, are needed to achieve effectiveness in reducing MMR.

The World Health Organization defined four priorities for making motherhood and childhood safe: reduce unsafe abortions, improve maternal health care, enhance the capacity of service utilization and timely treatment of obstetric emergencies.Citation20 Health education for pregnant women to understand why and when to seek treatment is also important, and community-based lecture tours by maternal and children's health centres may also be an effect intervention. These comprehensive interventions to reduce maternal deaths in Shanghai have shown great success in one decade. Now, we must share these experiences with the rest of China, especially in the central and western areas.

References

- C Ronsmans, WJ Graham, on behalf of Lancet Maternal Survival Series steering group. Maternal mortality: who, when, where, and why. Lancet. 368: 2006; 1189–1200.

- MC Hogan, KJ Foreman, M Naghavi. Maternal mortality for 181 countries, 1980–2008: a systematic analysis of progress towards Millennium Development Goal 5. Lancet. 375(9726): 2010; 1609–1623. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60518-1.

- G Yanqiu, C Ronsmans, A Lin. Time trends and regional differences in maternal mortality in China from 2000 to 2005. Bulletin of World Health Organization. 87: 2009; 913–920. Doi: 10.2471/BLT.08.060426.

- J Tan, M Qin, L Zhu. Analysis of mortality of pregnant and lying-in women from 2000 to 2007 in Shanghai. Journal of Chinese Maternity and Children's Healthcare. 23(28): 2008; 3954–3957. [in Chinese].

- Current Demographic Profiles of Shanghai, 2001–2011. Shanghai Municipal Population and Family Planning Commission. At: http://rkjsw.sh.gov.cn/spfpen/data/

- Shanghai Bureau of Health. Creation of low-cost maternity care in hospitals. At: http://wsj.sh.gov.cn/website/b/31848.shtml. [in Chinese].

- Shanghai Bureau of Health. Enhancement of the management of maternal health in migrant women. At: http://wsj.sh.gov.cn/website/b/34103.shtml. [in Chinese].

- International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems. 10th Revision. Geneva: World Health Organization, Geneva.

- LP Zhu, M Qin, WL Jia. Analysis of MMR of migrating population in Shanghai in recent 10 years. Journal of Chinese Maternity and Children's Healthcare. 22(20): 2007; 2751–2752. [in Chinese].

- WHO UNICEF UNFPA World Bank. Maternal mortality in 2005. 2007; World Health Organization: Geneva.

- N Prata, M Graff, A Graves. Avoidable maternal deaths: three ways to help now. Global Public Health. 4(6): 2009; 575–587.

- L Zhu, M Qin, L Du. Comparison of maternal mortality between migrating population and permanent residents in Shanghai, China, 1996–2005. BJOG. 116: 2009; 401–407.

- L Zhu, M Qin, W Jia. Whole coverage of maternal health management and effect in Shanghai. Journal of Chinese Maternity and Children's Healthcare. 23(10): 2008; 1321–1323. [in Chinese].

- World Health Organization. WHO recommendations for the prevention of post-partum haemorrhage. 2006; WHO: Geneva.

- L Du, M Qin, L Zhu. Analysis of maternal deaths due to post-partum haemorrhage (PPH) from 1997 to 2006 in Shanghai. Journal of Chinese Maternity and Children's Healthcare. 23(34): 2008; 4879–4882. [in Chinese].

- LP Zhu, J Tan, WL Jia. The effectiveness of low-cost pregnancy care for women from migrant populations at delivery hospitals in Shanghai. Chinese Health Resources. 10(2): 2007; 89–91. [in Chinese].

- LP Zhu, LP He, M Qin. Construction and effectiveness of emergency aid network in Shanghai. Journal of Chinese Maternity and Children's Healthcare. 25(2): 2010; 150–152. [in Chinese].

- M Qin, LP Zhu, L Zhang. Analysis of deaths due to ectopic pregnancy from 1979 to 2008 in Shanghai. Journal of Chinese Maternity and Children's Healthcare. 25(17): 2010; 2330–2333. [in Chinese].

- G Lewis. Beyond the numbers: reviewing maternal deaths and complications to make pregnancy safer. British Medical Bulletin. 67: 2003; 27–37.

- World Health Organization. Reduction of maternal mortality. A Joint WHO/UNFPA/UNICEF/World Bank statement. 1999; WHO: Geneva.