Efforts in recent decades have yielded noteworthy improvements in women’s and children’s health worldwide. Progress has been reported in reducing maternal mortality,Citation1 reducing under-five mortality,Citation2 increasing the use of contraceptives by womenCitation3 and increasing uptake of antenatal careCitation3. However, HIV and complications of pregnancy and childbirth remain the two leading causes of death for women of reproductive age worldwide.Citation4 Though the HIV epidemic has limited the success of some initiatives aimed at improving maternal and child health and survival, efforts to scale up HIV-related services – particularly comprehensive programs aimed at prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV (PMTCT) and the elimination of pediatric HIV – have contributed to reducing HIV-related maternalCitation5 and child mortality as well as providing broader benefits for women’s and children’s health.Citation1,6

Over 90% of pediatric HIV infections worldwide can be attributed to mother-to-child transmission (MTCT).Citation7 In the absence of any interventions, perinatal HIV infection will occur in 20–45% of infants born to HIV-positive mothers. This transmission can occur in utero, during childbirth or through breastfeeding. PMTCT efforts aim to reduce the risk of transmission during all three phases.Citation8 More than 90% of new pediatric HIV infections and nearly all HIV-related maternal deaths occur in low-and middle-income countries, and while PMTCT efforts have been dramatically scaled up over the past decade, the percentage of HIV-positive women in need of antiretrovirals (ARVs) for PMTCT or for their own health remains high.Citation9 In contrast, high-income countries have achieved near-elimination of new pediatric HIV infections and HIV-related maternal deaths through the use of highly effective interventions – most notably, ARVs – to prevent transmission and protect the health of HIV-positive women.Citation10 Given the successes achieved in high-income countries, there is a growing global consensus that with adequate commitment and financial support, virtual elimination of new HIV infections among children worldwide is possible in the near future. The call for elimination of new pediatric HIV infections provides a unique opportunity to address the four prongs of PMTCT in a comprehensive way, in part through supporting HIV-positive women – and their partners – to achieve their pregnancy intentions while protecting their own health and the health of their children.

This paper reviews the current literature on HIV and pregnancy from the standpoint of how efforts to eliminate new pediatric HIV infections can be leveraged to support HIV-positive women to achieve their pregnancy intentions. The paper provides an overview of global PMTCT efforts as well as commitments to eliminating new HIV infections in children and protecting maternal health. It then provides a summary of the literature on pregnancy intentions in the context of HIV in relation to two specific issues: preventing unintended pregnancies among HIV-positive women, and enabling HIV-positive women to have safer pregnancies. The paper concludes with a discussion of the policy and programmatic implications of the intensifying efforts to eliminate pediatric HIV, with consideration for how this relates to the pregnancy intentions of HIV-positive women.

Global commitments to eliminate new pediatric HIV infections and protect maternal health

Scaling up PMTCT efforts in resource-limited settings became an international goal in the late 1990s, after the short-course AZT and HIVNET 012 trials demonstrated the effectiveness of short-course ARVs for reduction of mother-to-child transmission of HIV.Citation11,12 In 1998, the United Nations defined a three-pronged strategy for preventing HIV infection in infants, calling for primary prevention of HIV among parents-to-be; prevention of unintended pregnancies among HIV-positive women; and prevention of HIV transmission from HIV-positive mothers to their infants.Citation13 This strategy was based on the best available scientific evidence at the time, but a myriad of health system, service delivery, sociocultural and client-level challenges hindered implementation of the strategy and achievement of adequate access to and uptake of PMTCT interventions. And although the strategy included primary prevention of HIV and prevention of unintended pregnancies, it did not address the long-term health needs of HIV-positive women or their families.

In 2003, in response to both persistent challenges and growing experience in the field of PMTCT, the United Nations called for a more comprehensive strategy to prevent HIV infection in infants and young children.Citation13 Since its introduction, this approach has been widely adopted by policy makers and program implementers alike. The expanded strategy added a fourth prong – care, treatment and support for HIV-positive women and their children – to the existing three, and further emphasized the need for integration of health services to effectively address all four prongs. The fourth prong was added in large part due to concerns that PMTCT programs had largely been focused on delivering short-course ARVs for the purposes of preventing HIV transmission to the infant, and the recognition that “on humanitarian grounds, it is difficult to defend providing a short course of antiretroviral drugs to save a child but denying basic care and, when indicated, antiretroviral treatment to the mother.Citation13 Moreover, it was acknowledged that HIV care and support services for mothers and their HIV-exposed infants could also help increase uptake of key health interventions (including PMTCT) in the future, thereby contributing to reducing the risk of HIV transmission and improving the health of mothers and their children.Citation13

In 2004, the Glion Call to ActionCitation14 articulated a multisectoral approach to linking reproductive health and HIV services; various other international guidelines and calls to action have since highlighted the need to bring these essential services together to more comprehensively address PMTCT and the health of HIV-positive women. While major stakeholders in the field of international PMTCT have worked to better address the first two prongs of the United Nations strategy, inadequate funding for comprehensive, integrated reproductive health and HIV services has hampered their efforts. This situation is consistent with a larger trend: funding for family planning and reproductive health has lagged behind investments in HIV over the past decade.Citation15 The Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation reported that in 2008, “the area of maternal, newborn and child health obtained half as much funding as HIV/AIDS.”Citation16 In fiscal year 2010, the US government appropriated $648.5 million for family planning (including a $55 million contribution to the United Nations Population Fund), $549 million for maternal and child health, and $5.7 billion for bilateral support of global HIV initiatives.Citation17 Recently, major donors have increased their financial commitments to broader maternal, newborn and child health (MNCH) efforts, including family planning and reproductive health. Canada’s Muskoka Initiative intends to pledge an additional $1.1 billion in new funding for MNCH activities between 2010 and 2015, and has called upon global donors to ultimately raise $5 billion in new funding.Citation18 Following the 2011 International Conference on Family Planning, the government of the UK pledged 35 million pounds to address family planning and unsafe abortion in the developing world.Citation19

One of the challenges in achieving the goals of the four-pronged strategy for PMTCT – in particular, prongs one and two – has been that while there is international policy support for integration of reproductive health, family planning and HIV, the funding streams remain separate.Citation20 For example, the United States President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief expresses support for family planning counseling and referrals for contraception, but funds cannot be used to support contraceptives themselves.Citation21 These discrepancies often result in vertical programming, with health services delivered in a parallel – not integrated – fashion. Stakeholders have identified the lack of funding for integration as a key barrier to delivering integrated services.Citation22 Some newer financial commitments, such as the Muskoka Initiative, provide funding for both family planning and PMTCT through integrated service delivery.Citation23 Achieving the four prongs and improving overall maternal and child health will require additional and sustained resources for integrated programming.

In 2009, UNAIDS called for virtual elimination of mother-to-child transmission of HIV by 2015; this goal also features prominently in the World Health Organization’s PMTCT strategic vision for 2010–2015.Citation24,25 Various multilateral agencies, governments, implementing organizations and civil society groups have added their voices to this call. During the June 2011 United Nations General Assembly High Level Meeting on AIDS, UNAIDS released the Global Plan towards the Elimination of New HIV Infections among Children by 2015 and Keeping Their Mothers Alive. This document was developed by a global task team co-chaired by UNAIDS and the Office of the US Global AIDS Coordinator. The team included representatives from United Nations agencies and 25 countries, as well as representatives from more than 30 international, private-sector and civil society organizations, including networks of people living with HIV.Citation26

In addition to addressing the prevention of new pediatric HIV infections, the Global Plan also emphasizes keeping women, including HIV-positive women, alive and healthy. This is notable, as evidence has long shown that child health and survival is inextricably linked to maternal health and survival.Citation27 The plan covers all low-and middle-income countries, but places special emphasis on the 22 countries with the highest estimated number of HIV-positive pregnant women. Although the plan notes that many developing countries have made “impressive progress” in rolling out programs to prevent MTCT of HIV, it also acknowledges that significant additional effort and human and financial resources are needed to accelerate this progress.Citation26 Since the Global Plan was introduced, it has received some criticism from activists and researchers for its approach to key issues of concern to HIV-positive women. However, as of this writing, several of the 22 priority countries had signed on to support the implementation of the Global Plan, primarily through the development of country-level strategies and plans.

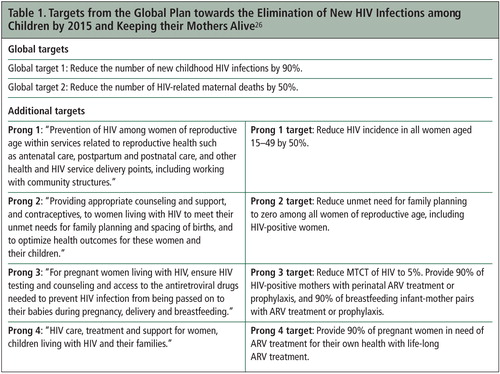

The goals laid out by the Global Plan are intended to be achieved by 2015, and the implementation framework for accomplishing these goals is based on the four-pronged strategy for PMTCT.Citation7,26,28 The plan includes two global targets plus one target for each of the four prongs (Table 1). The targets for prongs one and two apply to all women of reproductive age; the targets for prongs three and four are specifically focused on HIV-positive women.

Pregnancy intentions play an important role in determining the set of services needed to support and protect the health of an HIV-positive woman and her children, including but not limited to interventions to reduce the risk of MTCT. The Global Plan’s targets reinforce the requirement for health services to meet the needs of all women, taking into account their pregnancy intentions. To achieve these targets, efforts will be needed to further increase access to, uptake of, and quality of a variety of health services, including family planning counseling and commodities; voluntary and safe abortion and post-abortion care; pregnancy and delivery care; and HIV prevention, care, support and treatment. In particular, the targets listed under prongs three and four will require further expansion and integration of PMTCT interventions into MNCH services.

HIV and pregnancy desires

HIV-positive women, like all women, have the right to determine the number and spacing of their children.Citation14,29,30 A multitude of factors influence the desire for pregnancy among HIV-positive women, including but not limited to age; marital status; level of education; socioeconomic status; number of living children and deaths of previous children Citation31–35; perceived cultural significance of motherhood; perceived desires and attitudes of a woman’s partner, family and health care workersCitation36–39; stigma and discriminationCitation39; and the availability of ARVs for PMTCT or for a woman’s own health.Citation40,41 Social and familial pressure to have children is strong in many settings, but at the same time, research and programmatic and anecdotal evidence suggests that people living with HIV may be discouraged by health care providers or family members from having children in order to avoid the risk of transmitting HIV to infants or leaving orphans in the event that HIV causes the parents’ deaths.Citation29,39

When it comes to wanting to prevent pregnancy, a variety of factors influence women’s desire; many of these factors are the same regardless of HIV status. Specifically among HIV-positive women, the desire to prevent pregnancy may stem from concerns for their own health and the health of a potential childCitation42; wanting to avoid stigma and discrimination they may face for having a childCitation43–45; and wanting to avoid orphaning a potential child.Citation46 There are some data to suggest that HIV-positive men may also want to avoid becoming parents due to concerns about healthCitation47 and stigma.Citation43

The evidence is mixed as to whether an HIV-positive diagnosis and access to HIV-related services increase or decrease fertility desires. On one hand, there is considerable evidence that many HIV-positive women – and men – may continue to desire pregnancy and children despite their HIV status.Citation34,40,47–53 The availability of ARVs may increase this desireCitation40,41: for example, access to PMTCT services appears to increase fertility desires among some HIV-positive women to a level consistent with HIV-negative women.Citation54,55 However, there is also evidence that some women are more likely to want to limit childbearing after receiving an HIV-positive diagnosis. A recent study found that HIV-positive women in South Africa were 60% less likely to desire another pregnancy than HIV-negative women.Citation56 Similar results have been reported from Malawi, where a study found HIV-positive women to be 61% less likely to desire pregnancy than their HIV-negative counterparts.Citation57 The limited evidence on HIV-positive men’s pregnancy intentions generally indicates that HIV-positive men tend to want children more than their HIV-positive female counterparts.Citation36–38,52,58 More research is needed to explore men’s and couples’ views on pregnancy desires in the context of HIV.

The Global Plan notes that meeting unmet need for family planning among all women will contribute to preventing primary HIV infection among women of reproductive age, thus reducing the future need for ARVs for PMTCT and life-long treatment. One way in which this goal may be accomplished is by promoting barrier methods, such as condoms, for the dual purpose of preventing pregnancy and HIV infection. Furthermore, family planning services may provide an entry point for HIV testing and counseling, enabling individuals and couples to know their HIV status and receive information and education about safer sex practices. The Global Plan also emphasizes that HIV-positive women must be at the center of global and country-level strategies to eliminate pediatric HIV, and that these women must have access to family planning services and commodities.

Preventing unintended pregnancies among HIV-positive women

A key component of the Global Plan is to reduce the unmet need for family planning to zero among all women, thereby helping to prevent unintended pregnancies, space births and improve overall maternal and child health and survival.Citation26 Unmet need for family planning is an estimate of the percentage of women who would like to prevent or delay pregnancy but are not currently using contraception.Citation59 Although many HIV-positive women wish to prevent pregnancy, evidence suggests that unmet need for family planning may be higher among HIV-positive women than the general population.Citation60 Studies in Côte d’Ivoire, Rwanda, South Africa and Uganda have found levels of unintended pregnancies among HIV-positive women ranging from 51% to 91%.Citation60 A recent study in Malawi found that while HIV-positive women desire pregnancy less than HIV-negative women, the rate of pregnancy after one year was not different between the two groups, suggesting unmet contraceptive need, non-use or failure of a contraceptive method, or inability to negotiate contraceptive use.Citation57 Unintended pregnancies among HIV-positive women contribute to pediatric HIV infections because only about half of HIV-positive women worldwide receive PMTCT interventions despite the scale-up of PMTCT services in recent years.Citation61 For HIV-positive women who do not wish to become pregnant, prevention of unintended pregnancies through access to voluntary family planning can contribute to improving maternal health as well as reducing pediatric HIV infections.Citation62,63

Depending on their individual medical situation and needs, most HIV-positive women can safely use any contraceptive method; this includes short-and long-acting methods as well as permanent methods.Citation64 Concerns have been raised about the safety of hormonal contraceptives in the context of HIV. Some evidence suggests that using hormonal contraceptives may increase the likelihood that an HIV-positive woman will transmit HIV to an HIV-negative partner; that an HIV-positive woman may experience faster disease progression; or that an HIV-negative woman may be more susceptible to acquiring HIV.Citation65,66 However, based on an extensive review of the literature and an expert technical consultation, the World Health Organization (WHO) released updated recommendations in early 2012 declaring that “there are no restrictions on the use of any hormonal contraceptive method for women living with HIV or at high risk of HIV.”Citation67 These recommendations reaffirm the guidance provided in the WHO Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use,Citation64 and go a step further to emphasize that “couples seeking to prevent both unintended pregnancy and HIV should be strongly advised to use dual protection – condoms and another effective contraceptive method, such as hormonal contraceptives.”Citation67 By ensuring access to voluntary family planning services, including counseling about barrier methods such as condoms for dual protection, health services can help HIV-positive women and their partners who wish to avoid pregnancy achieve this intention while also contributing to reductions in both vertical and horizontal HIV transmission.

Safer pregnancy for HIV-positive women

For HIV-positive women who desire a pregnancy or are already pregnant, there are effective interventions that can protect their health and the health of their partners and children before, during and after pregnancy. For example, harm reduction strategies can be used to achieve conception while reducing the risk of HIV transmission between partners; essential maternal and newborn health interventions can help ensure safer pregnancy and childbirth; and ARVs can protect the health of HIV-positive mothers while also providing direct and indirect benefits for their HIV-exposed infants.

Achieving safer conception

In high-resource settings, assisted reproductive technologies have been successfully used to help HIV-affected couples more safely conceive a child while minimizing the risk of HIV transmission.Citation68 One such example is the use of artificial insemination, which allows for conception while not introducing the risk of horizontal HIV transmission from an HIV-positive woman to her HIV-negative male partner during unprotected intercourse.Citation69 Though shown to be effective in research and clinical settings in regions such as western Europe, these methods are not available in many of the settings with the highest burden of HIV worldwide; where they are available, cost and other limitations place them out of reach for many HIV-affected couples.

While there are no formal global guidelines specifically on safer conception in the context of HIV, current WHO guidelines on couples HIV testing and counseling provide recommendations on helping HIV-affected couples achieve safer conception. In addition to encouraging pre-conception counseling for HIV-affected couples, the guidelines state that ARVs should be recommended for HIV prevention purposes in sero-discordant couples who wish to conceive, even if the HIV-positive partner is not medically eligible for treatment.Citation70 Initiating an HIV-positive woman (or man) on ARVs, even if treatment is not indicated for disease management, can further suppress viral load, thus making transmission to the HIV-negative partner less likely.Citation68 Providing an HIV-negative partner with ARVs as pre-exposure prophylaxis has also been explored as a potentially effective strategy for preventing acquisition of HIV when attempting to conceive.Citation71 However, both of these interventions can be challenging in resource-constrained settings where ARVs may not be widely available or where clinical guidelines restrict treatment to only HIV-positive individuals who are medically eligible for treatment. The WHO guidelines on couples HIV testing and counseling note that the use of ARVs for reasons other than treatment “raises complex issues for both individuals and programs” and that equity and human rights concerns must be weighed.Citation70

Recent research has shown initial promising results regarding behavioral methods to reduce the risk of HIV transmission between sero-discordant partners who want to conceive. Behavioral strategies that help reduce – or in some cases eliminate – the risk of HIV transmission in sero-discordant couples include practices such as timed intercourse and “at-home” artificial insemination. The former refers to confining unprotected intercourse to when the woman is ovulating, and the latter refers to following simple procedures for couples to achieve insemination without intercourse, as when an HIV-negative male partner ejaculates into a condom that then can be inserted into the vagina of the HIV-positive partner.Citation68,72–75 Although these harm reduction strategies have the potential to enable HIV-affected couples to more safely achieve their fertility desires, they have not yet been extensively researched, and questions remain about their efficacy, feasibility and acceptability.

Preventing adverse maternal and perinatal outcomes

Studies suggest an association between HIV infection in pregnant women and adverse perinatal outcomes, but pregnancy does not appear to influence the mother’s HIV disease progression, according to a recent systematic review of the literature.Citation76,77 For women on ARV treatment, pregnancy may actually have a protective effect: women on treatment are less likely to experience HIV disease progression during pregnancy.Citation77 This does not mean, however, that HIV is inconsequential for a pregnant woman’s health. HIV both directly and indirectly impacts maternal mortality: directly by increasing the risk of pregnancy complications such as postpartum hemorrhage and puerperal sepsis, and indirectly by increasing a woman’s susceptibility to other infections such as malaria and tuberculosis.Citation78,79 A recent systematic analysis of maternal mortality rates and maternal deaths in 181 countries reported that while substantial progress had been achieved in reducing maternal deaths worldwide between 1980 and 2010, some countries with high HIV prevalence actually experienced increases in the maternal mortality ratio.Citation1 It has been reported that nearly one in every five maternal deaths occurs in HIV-positive women.Citation1 The body of evidence on HIV and maternal mortality and morbidity is growing, but developing a better understanding of this relationship will require both additional research and more effective ways of recording and tracking adverse outcomes.Citation29,80–83

Given the potential risks associated with HIV and pregnancy, ensuring comprehensive pregnancy care for HIV-positive women is essential. There is limited evidence on best practices for safe motherhood in the context of HIV. However, many of the same strategies for combating overall maternal mortality can be effective for reducing HIV-related maternal mortality. These include ensuring access to high-quality, high-impact MNCH interventions such as antenatal care, delivery with a skilled birth attendant, postpartum follow-up and additional life-saving services such as emergency obstetric care, if needed.Citation84 For HIV-positive women, this package of services must also include HIV prevention and treatment interventions in order to protect their own health as well as the health of their HIV-exposed infants.

Antiretrovirals for preventing pediatric HIV infection and protecting maternal health

The use of ARVs, both for prophylaxis and for treatment of the mother’s HIV disease, represents one of the most effective ways to prevent transmission of HIV from a mother to her infant, and to protect the mother’s own health.Citation25 Compared to previous versions, the current WHO guidelines on the use of ARVs for preventing MTCT and treating HIV-positive pregnant women place a greater emphasis on providing the most efficacious drug regimens – i.e., combination regimens – to protect maternal health and reduce the risk of HIV transmission to infants.Citation25 For women identified as HIV-positive during pregnancy, a CD4 count of less than or equal to 350 cells/mm3 warrants immediate initiation on antiretroviral therapy for their own health, according to WHO guidelines.Citation85 Identifying treatment-eligible pregnant women is particularly important as these women are more likely to pass HIV to their infants during pregnancy, delivery and breastfeeding due to their high viral load. The Global Plan’s goal to reach 90% of these women with ARV treatment for their own disease will have multiple benefits for the women themselves as well as their children. First and foremost, it will improve and preserve the woman’s health. By suppressing a woman’s viral load and improving her overall health, ARV treatment also dramatically decreases the likelihood of mother-to-child transmission occurring in utero, during delivery and through breastfeeding. Finally, HIV-positive women who are on treatment have a decreased risk of death compared to eligible women who do not receive ARV treatment; this in turn decreases the likelihood that their children will become orphans.Citation86

If an HIV-positive pregnant woman has a CD4 cell count above 350 cells/mm3 and thus is not advised to initiate ARV treatment for her own health, then WHO recommends the use of one of two regimens to reduce the risk of HIV transmission during pregnancy, delivery and breastfeeding. The first regimen (“Option A”) is maternal ARV prophylaxis starting at 14 weeks of pregnancy and continuing through delivery, followed by extended infant ARV prophylaxis from birth until one week after the cessation of breastfeeding. The second (“Option B”) is a maternal triple ARV regimen (“treatment as prophylaxis”) starting at 14 weeks of pregnancy and continuing until one week after the cessation of breastfeeding, with the infant receiving ARV prophylaxis from birth to six weeks.Citation85

In April 2012, WHO published a programmatic update in which it presented information on a third PMTCT option, referred to as “Option B+.” This approach calls for initiating HIV-positive pregnant women on ARV “treatment as prophylaxis” regardless of their CD4 cell count and continuing the regimen for life; the infant regimen for Option B+ is the same as in Option B. Potential benefits of Option B+ include continuing protection against horizontal transmission as well as earlier protection against MTCT in future pregnancies. This option also may benefit the woman’s health by starting treatment earlier and avoiding the risks associated with starting and stopping ARVs. While the programmatic update does not replace the current WHO guidelines on this topic, it does introduce important considerations about the potential benefits of Option B+, particularly for HIV-positive women who are not yet treatment-eligible and who may desire a pregnancy in the future.Citation87

In 2009, 53% of HIV-positive pregnant women in low-and middle-income countries received ARVs to reduce the risk of HIV transmission to their infants. While this figure represents an increase from 45% in 2008 and 15% in 2005, it also includes less efficacious regimens such as single-dose nevirapine.Citation9 More recent estimates exclude data on single-dose nevirapine, which is no longer recommended by WHO. An estimated 48% of HIV-positive pregnant women in low-and middle-income countries received combination ARVs for PMTCT in 2010; when data on single-dose nevirapine are included, PMTCT coverage in these countries was estimated at 59%.Citation61 However, the proportion of pregnant women in need of ARV treatment for their own health who are actually receiving it remains low.Citation9 These data indicate that nearly half of all HIV-positive pregnant women may not be receiving any interventions to prevent MTCT of HIV and protect their own health.

Conclusion

Noteworthy progress has been made in improving the health of women and children through the expansion of MNCH, reproductive health (including voluntary family planning and safe abortion), and HIV programs, but significant efforts are still needed to achieve Millennium Development Goals 4, 5, and 6. HIV and complications of pregnancy and childbirth remain the two leading causes of death for women of reproductive age worldwideCitation4; this can be attributed in part to inadequate availability of, limited access to, and poor quality of essential health services. The growing global commitment to eliminate new pediatric HIV infections provides an opportunity to build on momentum around HIV and MNCH programs to improve maternal and child health and survival, in part by taking into account the pregnancy intentions of HIV-positive women.

The Global Plan Towards the Elimination of New HIV Infections Among Children by 2015 and Keeping Their Mothers Alive includes targets of reaching 90% of non-treatment-eligible and 90% of treatment-eligible pregnant women with appropriate ARV interventions to prevent MTCT of HIV and protect their own health.Citation26 There is evidence to suggest that the availability of HIV services, including the availability of ARVs, plays a role in the pregnancy intentions of HIV-positive women.Citation39 Increasing the availability, accessibility and quality of these services may help women and their partners make more informed decisions about having children. Efforts to design, deliver and measure HIV and MNCH services must take into account the pregnancy intentions of HIV-positive women and their partners by offering voluntary family planning counseling and commodities for prevention of unintended pregnancies, as well as counseling and support on ways to reduce risk of HIV transmission between partners and to infants, and on ways to stay healthy during pregnancy.Citation88 The Global Plan stresses the importance of ensuring that “all women, especially pregnant women, have access to quality life-saving HIV prevention and treatment services.” The plan and the 2010 WHO guidelines on PMTCT note that strong linkages between MNCH services and HIV services will be required to accomplish this.Citation26,85 While PMTCT interventions have long been integrated within MNCH services (for example, offering HIV testing and counseling during antenatal care), further integration of MNCH and HIV efforts represents an opportunity to strengthen safe motherhood interventions and increase access to and uptake of these critical services.

Eliminating pediatric HIV will require a comprehensive approach to empower HIV-positive women to fulfill their pregnancy intentions, whether this involves preventing pregnancy or safely expanding their families. For the targets set forth in the Global Plan to be achieved, strong linkages between family planning, reproductive and obstetric care, and HIV-related services will be essential. In addition to providing clients with more comprehensive and complete health care, linkages between these services can also contribute to strengthening overall health systems, program scale-up, sustainability and effectiveness.Citation89,90 Where these efforts have historically functioned as separate or vertical programs, the global call for the elimination of pediatric HIV provides an unprecedented opportunity to bring them together to better support the pregnancy intentions and health needs of HIV-positive women.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge our colleagues at the Elizabeth Glaser Pediatric AIDS Foundation for their support in preparing this paper. In particular, we would like to thank RJ Simonds and Catherine Connor for their expert guidance, as well as Alexandra Ekblom for her editorial assistance.

References

- MC Hogan, KJ Foreman, M Naghavi. Maternal mortality for 181 countries, 1980–2008: a systematic analysis of progress towards Millennium Development Goal 5. The Lancet. 375(9726): 2010 May 8; 1609–1623.

- D You, G Jones, K Hill. Levels and trends in child mortality, 1990–2009. The Lancet. 376(9745): 2010 Sep 18; 931–933.

- United Nations. Millennium Development Goals report 2010. At: www.un.org/millenniumgoals/pdf/MDG%20Report%202010%20En%20r15%20-low%20res%2020100615%20-.pdf Accessed 5 June 2012

- WHO. Women and health: today’s evidence tomorrow’s agenda. 2009. At: http://www.who.int/gender/women_health_report/en/index.html Accessed 27 May 2012

- R Lozano, H Wang, KJ Foreman. Progress towards Millennium Development Goals 4 and 5 on maternal and child mortality: an updated systematic analysis. The Lancet. 378(9797): 2011 Sep 24; 1139–1165.

- LF Johnson, MA Davies, H Moultrie. The effect of early initiation of antiretroviral treatment in infants receiving pediatric auto immune deficiency syndrome mortality in South Africa: a model-based analysis. Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal. 31(5): 2012 May; 474–480.

- WHO UNICEF. Guidance on global scale-up of the prevention of mother to child transmission of HIV: towards universal access for women, infants, and young children and eliminating HIV and AIDS among children. 2007. At: www.unicef.org/aids/files/PMTCT_enWEBNov26.pdf. Accessed 5 June 2012

- KM De Cock, MG Fowler, E Mercier. Prevention of mother-to-child HIV transmission in resource-poor countries: translating research into policy and practice. Journal of the American Medical Association. 283(9): 2000 Mar 1; 1175–1182.

- UNAIDS. Report on the global AIDS epidemic 2010. At: http://www.unaids.org/documents/20101123_GlobalReport_em.pdf Accessed 19 January 2012

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Pregnancy and childbirth. 2007. At: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/topics/perinatal/index.htm Accessed 27 May 2012

- LA Guay, P Musoke, T Fleming. Intrapartum and neonatal single-dose nevirapine compared with zidovudine for prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV-1 in Kampala, Uganda: HIVNET 012 randomised trial. The Lancet. 354(9181): 1999 Sep 4; 795–802.

- N Shaffer, R Chuachoowong, PA Mock. Short-course zidovudine for perinatal HIV-1 transmission in Bangkok, Thailand: a randomised controlled trial. Bangkok Collaborative Perinatal HIV Transmission Study Group. The Lancet. 353(9155): 1999 Mar 6; 773–780.

- WHO. Strategic approaches to the prevention of HIV infection in infants: report of a WHO meeting, Morges, Switzerland, 20–22 March 2002. 2003. At: http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/mtct/strategic/en/index.html Accessed 27 May 2012

- UNFPA. Glion call to action on family planning and HIV/AIDS in women and children. 2004. At: http://www.unfpa.org/public/publications/pid/1435.html Accessed 5 June 2012

- SA Cohen. Hiding in plain sight: the role of contraception in preventing HIV. Guttmacher Policy Review. 11(1): 2008

- Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation. Financing global health 2011: continued growth as MDG deadline approaches. Seattle, WA, USA; 2011.

- Center for Health and Gender Equity. Foreign assistance budget. 2012. At: http://www.genderhealth.org/the_issues/us_foreign_policy/foreign_assistance_budget/ Accessed 10 January 2012

- Canadian International Development Agency. Maternal, newborn and child health. 2010. At: http://www.acdi-cida.gc.ca/acdi-cida/acdi-cida.nsf/eng/FRA-127113657-MH7 Accessed 27 May 2012

- The Guardian. UK pledges £35m for family planning for poor countries. Dakar, Senegal; 2011. At: http://www.guardian.co.uk/global-development/2011/nov/29/uk-pledge-money-for-family-planning Accessed 10 January 2012

- R Wilcher, T Petruney, HW Reynolds. From effectiveness to impact: contraception as an HIV prevention intervention. Sexually Transmitted Infections. 84(Suppl 2): 2008 Oct; ii54–ii60.

- HD Boonstra. Linkages between HIV and family planning services under PEPFAR: room for improvement. Guttmacher Policy Review. 14(4): 2011

- T Petruney, SV Harlan, M Lanham. Increasing support for contraception as HIV prevention: stakeholder mapping to identify influential individuals and their perceptions. PLoS ONE. 5(5): 2010; e10781.

- UNICEF. The G8 Muskoka initiative: maternal, newborn and under-five child health. 26 June 2010. At: www.unicef.org/media/files/G8_MUSKOKA_INITIATIVE.doc Accessed 27 May 2012

- UNAIDS. UNAIDS calls for a virtual elimination of mother to child transmission of HIV by 2015. 21 May 2009. At: http://www.unaids.org/en/Resources/PressCentre/Pressreleaseandstatementarchive/2009/May/20090521PriorityAreas/ Accessed 27 May 2012

- WHO. PMTCT strategic vision 2010–2015: preventing mother-to-child transmission of HIV to reach the UNGASS and Millennium Development Goals. 2010. At: http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/mtct/strategic_vision/en/index.html Accessed 5 June 2012

- UNAIDS. Countdown to zero: global plan towards the elimination of new HIV infections among children by 2015 and keeping their mothers alive. 2011. At: www.unaids.org/en/media/unaids/contentassets/documents/unaidspublication/2011/20110609_JC2137_Global-Plan-Elimination-HIV-Children_en.pdf Accessed 22 April 2012

- Family Care International. A systematic review of the interconnections between maternal and newborn health. 2011. At: http://familycareintl.org/UserFiles/File/System_Rev_FINAL.pdf Accessed 27 May 2012

- UNICEF. Preventing mother to child transmission (PMTCT). 2010. At: http://www.unicef.org/aids/index_preventionyoung.html Accessed 5 June 2012

- The pregnancy intentions of HIV-positive women: forwarding the research agenda [conference report]. 2010 March 17–19; Harvard School of Public Health, Boston, MA.

- UNFPA. Report of the International Conference on Population and Development. 1995. At: http://www.unfpa.org/public/cache/offonce/home/sitemap/icpd/International-Conference-on-Population-and-Development/ICPD-Programme;jsessionid=CC9EAED47AC499F4CA26168298309DCB.jahia01 Accessed 27 May 2012

- S Allen, J Meinzen-Derr, M Kautzman. Sexual behavior of HIV discordant couples after HIV counseling and testing. AIDS. 17(5): 2003 Mar 28; 733–740.

- C Baylies. The impact of HIV on family size preference in Zambia. Reproductive Health Matters. 8(15): 2000 May; 77–86.

- T Delvaux, C Nostlinger. Reproductive choice for women and men living with HIV: contraception, abortion and fertility. Reproductive Health Matters. 15(29 Suppl): 2007 May; 46–66.

- L Panozzo, M Battegay, A Friedl. High risk behaviour and fertility desires among heterosexual HIV-positive patients with a serodiscordant partner – two challenging issues. Swiss Medical Weekly. 133(7–8): 2003 Feb 22; 124–127.

- N Smee, AK Shetty, L Stranix-Chibanda. Factors associated with repeat pregnancy among women in an area of high HIV prevalence in Zimbabwe. Women’s Health Issues. 21(3): 2011 May–Jun; 222–229.

- R Bunnell, JP Ekwaru, P Solberg. Changes in sexual behavior and risk of HIV transmission after antiretroviral therapy and prevention interventions in rural Uganda. AIDS. 20(1): 2006 Jan 2; 85–92.

- M Hollos, U Larsen. Which African men promote smaller families and why? Marital relations and fertility in a Pare community in Northern Tanzania. Social Science and Medicine. 58(9): 2004 May; 1733–1749.

- S Nakayiwa, B Abang, L Packel. Desire for children and pregnancy risk behavior among HIV-infected men and women in Uganda. AIDS and Behavior. 10(4 Suppl): 2006 Jul; S95–S104.

- B Nattabi, J Li, SC Thompson. A systematic review of factors influencing fertility desires and intentions among people living with HIV/AIDS: implications for policy and service delivery. AIDS and Behavior. 13(5): 2009 Oct; 949–968.

- J Homsy, R Bunnell, D Moore. Reproductive intentions and outcomes among women on antiretroviral therapy in rural Uganda: a prospective cohort study. PLoS ONE. 4(1): 2009; e4149.

- FE Makumbi, G Nakigozi, SJ Reynolds. Associations between HIV antiretroviral therapy and the prevalence and incidence of pregnancy in Rakai, Uganda. AIDS Research and Treatment. 2011: 2011; 519492.

- C Baek, N Rutenberg. Addressing the family planning needs of HIV-positive PMTCT clients: baseline findings from an operations research study. Washington DC; 2005. At: www.popcouncil.org/pdfs/horizons/fppmtctnairobi.pdf Accessed 5 June 2012

- D Cooper, J Harries, L Myer. “Life is still going on”: reproductive intentions among HIV-positive women and men in South Africa. Social Science and Medicine. 65(2): 2007; 274–283.

- R Feldman, C Maposhere. Safer sex and reproductive choice: findings from “positive women: voices and choices” in Zimbabwe. Reproductive Health Matters. 11(22): 2003 Nov; 162–173.

- P Oosterhoff, NT Anh, NT Hanh. Holding the line: family responses to pregnancy and the desire for a child in the context of HIV in Vietnam. Culture, Health and Sexuality. 10(4): 2008 May; 403–416.

- S Kanniappan, MJ Jeyapaul, S Kalyanwala. Desire for motherhood: exploring HIV-positive women’s desires, intentions and decision-making in attaining motherhood. AIDS Care. 20(6): 2008 Jul; 625–630.

- V Paiva, EV Filipe, N Santos. The right to love: the desire for parenthood among men living with HIV. Reproductive Health Matters. 11(22): 2003 Nov; 91–100.

- JL Chen, KA Philips, DE Kanouse. Fertility desires and intentions of HIV-positive men and women. Family Planning Perspectives. 33(4): 2001 Jul–Aug; 144–152, 165.

- J Lifshay, S Nakayiwa, R King. Partners at risk: motivations, strategies, and challenges to HIV transmission risk reduction among HIV-infected men and women in Uganda. AIDS Care. 21(6): 2009 Jun; 715–724.

- Mbatia R, Antelman G, Pals S, et al. Unmet need for family planning and low rates of dual method protection among men and women attending HIV care and treatment services in Kenya, Namibia and Tanzania. 6th International AIDS Conference on Pathogenesis, Treatment and Prevention; 2011 July 17–20; Rome.

- L Myer, K Rebe, C Morroni. Missed opportunities to address reproductive health care needs among HIV-infected women in antiretroviral therapy programmes. Tropical Medicine and International Health. 12(12): 2007 Dec; 1484–1489.

- V Paiva, N Santos, I Franca-Junior. Desire to have children: gender and reproductive rights of men and women living with HIV: a challenge to health care in Brazil. AIDS Patient Care and STDS. 21(4): 2007 Apr; 268–277.

- UNAIDS. Report on the Global AIDS Epidemic 2008. At: http://www.unaids.org/en/media/unaids/contentassets/dataimport/pub/globalreport/2008/jc1510_2008globalreport_en.zip Accessed 27 May 2012

- D Cooper, J Moodley, V Zweigenthal. Fertility intentions and reproductive health care needs of people living with HIV in Cape Town, South Africa: Implications for integrating reproductive health and HIV care services. AIDS and Behavior. 13(Suppl 1): 2009 Jun; 38–46.

- M Maier, I Andia, N Emenyonu. Antiretroviral therapy is associated with increased fertility desire, but not pregnancy or live birth, among HIV-positive women in an early HIV treatment program in rural Uganda. AIDS and Behavior. 13(Suppl 1): 2009 Jun; 28–37.

- A Kaida, F Laher, SA Strathdee. Childbearing intentions of HIV-positive women of reproductive age in Soweto, South Africa: the influence of expanding access to HAART in an HIV hyperendemic setting. American Journal of Public Health. 101(2): 2011 Feb; 350–358.

- F Taulo, M Berry, A Tsui. Fertility intentions of HIV-1 infected and uninfected women in Malawi: a longitudinal study. AIDS and Behavior. 13(Suppl 1): 2009 Jun; 20–27.

- L Sherr. Fathers and HIV: considerations for families. Journal of the International AIDS Society. 13(Suppl 2): 2010; S4.

- World Health Organization IPPF-WHR. Glossary. 2011. At: http://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/topics/family_planning/unmet_need_fp/en/index.html Accessed 5 June 2012

- R Wilcher, W Cates Jr. Reaching the underserved: family planning for women with HIV. Studies in Family Planning. 41(2): 2010 Jun; 125–128.

- WHO UNICEF UNAIDS. Progress report 2011: Global HIV/AIDS response – epidemic update and health sector progress towards universal access. 2011. At: http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/progress_report2011/en/index.html Accessed 27 May 2012

- DT Halperin, J Stover, HW Reynolds. Benefits and costs of expanding access to family planning programs to women living with HIV. AIDS. 23(Suppl 1): 2009 Nov; S123–S130.

- W Hladik, J Stover, G Esiru. The contribution of family planning towards the prevention of vertical HIV transmission in Uganda. PLoS ONE. 4(11): 2009; e7691.

- WHO. Medical eligibility criteria for contraceptive use. 2010. At: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2010/9789241563888_eng.pdf Accessed 27 May 2012

- Heffron R, Donnell D, Rees H, et al. Hormonal contraceptive use and risk of HIV-1 transmission: a prospective cohort analysis. 6th International AIDS Conference on Pathogenesis, Treatment and Prevention; 2011 July 17–20; Rome.

- R Heffron, E Were, C Celum. A prospective study of contraceptive use among African women in HIV-1 serodiscordant partnerships. Sexually Transmitted Diseases. 37(10): 2010 Oct; 621–628.

- WHO. Hormonal contraception and HIV: technical statement. 2012. At: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/hq/2012/WHO_RHR_12.08_eng.pdf Accessed 27 May 2012

- LT Matthews, JS Mukherjee. Strategies for harm reduction among HIV-affected couples who want to conceive. AIDS and Behavior. 13(Suppl 1): 2009 Jun; 5–11.

- L Bujan, L Hollander, M Coudert. Safety and efficacy of sperm washing in HIV-1-serodiscordant couples where the male is infected: results from the European CREAThE network. AIDS. 21(14): 2007 Sep 12; 1909–1914.

- WHO. Guidance on couples HIV testing and counselling including antiretroviral therapy for treatment and prevention in serodiscordant couples: recommendations for a public health approach. 2012. At: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2012/9789241501972_eng.pdf Accessed 27 May 2012

- LT Matthews, JM Baeten, C Celum. Periconception pre-exposure prophylaxis to prevent HIV transmission: benefits, risks, and challenges to implementation. AIDS. 24(13): 2010 Aug 24; 1975–1982.

- A Anglemyer, GW Rutherford, RC Baggaley. Antiretroviral therapy for prevention of HIV transmission in HIV-discordant couples. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 8: 2011; CD009153.

- MS Cohen, YQ Chen, M McCauley. Prevention of HIV-1 infection with early antiretroviral therapy. New England Journal of Medicine. 365(6): 2011 Aug 11; 493–505.

- SM Hammer. Antiretroviral treatment as prevention. New England Journal of Medicine. 365(6): 2011 Aug 11; 561–562.

- MA Lampe, DK Smith, GJ Anderson. Achieving safe conception in HIV-discordant couples: the potential role of oral preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP) in the United States. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 204(6): 2011 Jun; 488 e1–488 e8.

- P Brocklehurst, R French. The association between maternal HIV infection and perinatal outcome: A systematic review of the literature and meta-analysis. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 105(8): 1998; 836–848.

- S MacCarthy, F Laher, M Nduna. Responding to her question: a review of the influence of pregnancy on HIV disease progression in the context of expanded access to HAART in sub-Saharan Africa. AIDS and Behavior. 13(Suppl 1): 2009 Jun; 66–71.

- J McIntyre. Mothers infected with HIV. British Medical Bulletin. 67: 2003; 127–135.

- J McIntyre. Maternal health and HIV. Reproductive Health Matters. 13(25): 2005 May; 129–135.

- Q Abdool-Karim, C Abouzahr, K Dehne. HIV and maternal mortality: turning the tide. The Lancet. 375(9730): 2010 Jun 5; 1948–1949.

- M Berer. HIV/AIDS, pregnancy and maternal mortality and morbidity: implications for care. M Berer, TK Sundari Ravindran. Safe motherhood initiatives: critical issues. 1999; England Blackwell Science: Oxford, 198–210.

- C Eyakuze, DA Jones, AM Starrs. From PMTCT to a more comprehensive AIDS response for women: a much-needed shift. Developing World Bioethics. 8(1): 2008 Apr; 33–42.

- JE Rosen, I de Zoysa, K Dehne. Understanding methods for estimating HIV-associated maternal mortality. Journal of Pregnancy. 2012: 2012; 958262.

- J Moodley, RC Pattinson, C Baxter. Strengthening HIV services for pregnant women: an opportunity to reduce maternal mortality rates in Southern Africa/sub-Saharan Africa. BJOG: an International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 118(2): 2011 Jan; 219–225.

- WHO. New guidance on prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV and infant feeding in the context of HIV. 2010. At: http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/mtct/PMTCTfactsheet/en/index.html Accessed 27 May 2012

- N Siegfried, L van der Merwe, P Brocklehurst. Antiretrovirals for reducing the risk of mother-to-child transmission of HIV infection. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 7: 2011; CD003510.

- WHO. Programmatic update: use of antiretroviral drugs for treating pregnant women and preventing HIV infection in infants: executive summary. 2012. At: http://www.who.int/hiv/PMTCT_update.pdf Accessed 27 May 2012

- D Cooper, J Moodley, V Zweigenthal. Fertility intentions and reproductive health care needs of people living with HIV in Cape Town, South Africa: implications for integrating reproductive health and HIV care services. AIDS and Behavior. 13(Suppl 1): 2009 Jun; 38–46.

- Adjorlolo-Johnson G, Wahl A, Ramachandran S. Care and treatment site characteristics associated with optimal enrollment of HIV-infected children. XVIII International AIDS Conference; 2010 July 18–23; Vienna.

- J Mermin, W Were, JP Ekwaru. Mortality in HIV-infected Ugandan adults receiving antiretroviral treatment and survival of their HIV-uninfected children: a prospective cohort study. The Lancet. 371(9614): 2008 Mar 1; 752–759.