For young women living with HIV, being able to prevent, delay or space pregnancies is an essential component of health management and the prevention of onward transmission of HIV to infants and partners.Citation1–5 In Zimbabwe, where HIV prevalence nationally is 15%, and young women experience up to three times higher HIV prevalence than their male peers, there remains a critical need for sexual and reproductive health services that meet the family planning and HIV care concerns of this population.Citation6 Country-wide, unsatisfied demand for family planning services remains highest among young women aged 15–19.Citation6 Limited health facilities, a shortage of health care workers, lack of transportation and inability to pay for services are central to the problem. Additionally, provider prejudice against young unmarried women using contraception plays a key role in deterring young women from accessing services.Citation1,6–8

In the Shona culture of Zimbabwe, a high regard for childbearing contributes to strong pressure from partners and families to have children. For young women living with HIV, consequently, disclosure of HIV status can be a central strategy to garner support for controlling fertility.Citation5 A study exploring experiences of disclosure among a cohort of women receiving HIV treatment at Chitungwiza National Hospital in Zimbabwe identified fear of stigma, violence or divorce as a barrier to disclosure to partners.Citation9 Despite these fears, 78% of women in the study disclosed to their current husband or boyfriend, with the majority of partners reacting positively to the news. However, among young women aged 18–27, only 20% disclosed to their partner, suggesting that perceived risks and benefits of disclosure might differ by age.Citation9

More information is needed to understand how young women living with HIV weigh disclosure in the context of forming partnerships, avoiding or delaying pregnancy, or achieving desired family size with infants born free from HIV. This paper reports findings from qualitative interviews with 28 young women aged 16–20 living with HIV in urban Zimbabwe, and discusses how findings can contribute to better policies and programs for this important population.

Methodology

This qualitative study is nested within the ongoing SHAZ!-Plus intervention trial, conducted by the Pangaea Global AIDS Foundation and the Zimbabwe AIDS Prevention Programme of the University of Zimbabwe with funding from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. Since 2000, SHAZ! (Shaping the Health of Adolescents in Zimbabwe) has examined the effects of combined life skills education and economic opportunities on HIV outcomes among orphaned and vulnerable young women in Zimbabwe. Issues of interest include economic indicators; treatment adherence and overall health status; sexual and reproductive health outcomes; and prevention of onward transmission of HIV to infants and partners.Citation10 In the current trial, young women aged 16–19 living with HIV are randomized to either receive health education and medical care (control group) or these services plus an enhanced life-skills intervention,Citation11,12 vocational training and a micro-grant (intervention group).

SHAZ!-Plus participants live in Chitungwiza, an urban community on the outskirts of Harare with an estimated population of 321,782.Citation13 Participants receive medical care at Chitungwiza National Hospital, which has an HIV clinic, an antenatal care clinic and a reproductive health clinic. Current HIV prevalence data for the area are not available.

Qualitative study cohort

Our qualitative sub-study recruited 28 participants from among those already enrolled in the SHAZ!-Plus study: half from the control group and half from the intervention group. We oversampled participants with a history of pregnancy (21/28) to ensure a range of experiences with fertility. At the time recruitment for the qualitative study took place, approximately 300 young women had enrolled in SHAZ!-Plus (which later achieved its target enrollment of 710 participants). All participants provided informed consent, and ethical review committees in Zimbabwe and the United States approved the research.

Data collection

Two Zimbabwean women researchers experienced in qualitative data collection conducted in-depth interviews in Shona, the participants’ preferred language, using a semi-structured, open-ended guide. The interview guide was written in English and translated into Shona. It explored participants’ desires in terms of starting or expanding a family, as well as how those desires may be shaped by HIV or health status, family and partner expectations, and community norms around childbearing. Each interview involved a participant, an interviewer and a note-taker, and interviews were tape-recorded. Interviews ranged from 23 minutes to 62 minutes, with the majority (26/28) lasting 45 minutes or longer. Quantitative data on orphaned or vulnerable child status were collected from participants at the time of enrollment in SHAZ!-Plus, while the remainder of the quantitative data reported in this paper were collected during qualitative interviews.

Data analysis

The tape-recorded interviews were transcribed in Shona and translated into English. The SHAZ!-Plus study director (I. Mudekunye-Mahaka), who conducted half of the interviews, checked transcript translations for accuracy. Two coders, the study director and one outside coder not involved in data collection (S. Zamudio-Haas), collaborated with the other authors to analyze transcripts in accordance with a grounded theory approach to identify and understand emergent themes.Citation14 Data were coded by hand and then organized by code and category. Memos were utilized at each stage to develop salient theoretical categories and explore relationships among categories. Initial analysis led to the development of a standard codebook, including a definition, inclusion criteria, exclusion criteria and examples for each code.Citation15 The coders separately applied the standard codebook to three of the same transcripts. Discrepancies were discussed until consensus was reached, and the inclusion and exclusion criteria were clarified to ensure uniform coding for the entire sample of interviews.

Results

Quantitative information

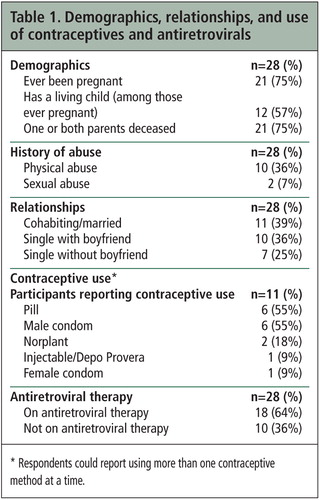

At the time of the in-depth interviews, study participants ranged in age from 16 to 20, with a mean age of 18 (standard deviation, 1.0) (data not shown). Three-quarters had had a previous pregnancy (21/28) (Table 1). Three-quarters had lost one or both parents (21/28). A little over one-third reported histories of physical abuse (10/28) or sexual abuse (2/28). Most participants were in relationships at the time they were interviewed: 11 were cohabiting or married, and 10 of the remaining 17 had steady boyfriends. A little under half of interview participants reported any contraceptive use (11/28), with condoms (6/28) and oral contraceptive pills (6/28) the most popular methods used. Eighteen of 28 participants were taking antiretroviral therapy.

Community and family norms related to childbearing

Regardless of participants’ current relationship status, they described community and family norms that place childbearing at the center of a young woman’s life. In Shona culture, young couples are encouraged and expected to expand their families soon after marriage, and they often live with the man’s family before establishing their own household. Participants talked about a new wife’s value to the man’s family being connected to her ability to reproduce. In-laws were reported to deride a young wife who does not bear children as “wasting our food.” Both married and single participants said that families and communities closely watch newly cohabiting couples; if pregnancy fails to occur soon after marriage, community gossip places blame on the woman. Participants noted that if a woman does not bear children, her husband might threaten to leave her or take on additional wives.

“There will be pressure because people expect that after marriage a couple will have children… If they are unaware of it [someone’s HIV-positive status] they will keep piling on the pressure. The man’s family will suggest to him that he takes in another wife who can have children since this one can’t have children.” (Age 18)

Disclosure of HIV status to male partners: high stakes, high risk

Disclosure of HIV status to partners – regardless of study participants’ current relationship status – emerged as a central theme, with disclosure considered critical for carrying out fertility intentions and preventing HIV transmission to partners and infants. Young women discussed disclosure as a turning point in romantic relationships, talking about their hopes that partners would respond with support while also articulating fears of rejection or violence. Most participants (19/28) had disclosed to either a current or former boyfriend or husband, and some to more than one partner; a total of 23 disclosure experiences were described. Disclosure resulted in a range of responses, from extremely negative and abusive to reassuring and caring. Of the nine participants who had never disclosed in a relationship, one was single and had never had a romantic relationship, one had learned her HIV status after a recent break-up and had been single since then, and the remaining seven chose not to disclose to current and/or former partners due to anticipated negative outcomes.

About half of disclosure experiences (11/23) in either current or past relationships had resulted in adverse reactions from men, such as anger, physical or sexual violence, or break-ups. Verbal abuse included threats to turn the participant out of the house or take away children. Eight women endured ongoing abuse following disclosure. In two of these cases, abuse drove women out of the home. Four other women were abandoned.

“We were staying together and he left me when I was seven months gone [pregnant] after I told him… He just said he was leaving for work and would come back. I haven’t seen him since.” (Age 19)

Men’s negative reactions often included disclosing the female partner’s HIV status without her consent to family members or other community members. Participants described their partners angrily announcing their HIV status publicly, causing humiliation and distress. One participant recounted how her partner took her to the shopping center where his family worked following her HIV test, and against her wishes announced the test results to relatives who then suggested he throw her out of the home.

“My husband kept saying things to me like, ‘Pack your things and go, I don’t love you anymore.’ His relatives told him, ‘How can you stay with a snake in your house?… Leave her at the roundabout close to the taxi rank; she will figure out where to go.’” (Age 19)

Among the 21 participants currently in relationships, 12 had disclosed their HIV status to their husband or boyfriend. While a number of partners initially had reacted with anger and hostility, most ended up being supportive. Only two participants currently in relationships reported ongoing abuse, and about half of partners underwent HIV testing after the participant’s disclosure (these experiences are described in more detail below). Participants who were in relationships and received compassionate or understanding responses to disclosure highlighted how their partners helped safeguard their health in different ways, such as providing medication adherence support and taking them to the clinic when they need care.

“I disclosed to [my boyfriend] and he said he had no problem with that… He said we would both go for the test but he loves me anyway. He sometimes calls me to ask if I have taken my medication.” (Age 20)

The nine participants who were in relationships but had not discussed their HIV status with their current partner described feeling stress and fear about disclosure. They were afraid that their partners would stop loving them, take other wives or girlfriends, or throw them out. One young woman recounted her family’s fear that they would need to return lobola (bride price) if the husband found out her HIV status.

Participants not currently in a relationship described preferring to stay single until finding someone who would be supportive and accepting of their HIV status. Only one of these seven women had never had a boyfriend or husband. She talked about waiting before settling down and finding a partner, and about remaining a virgin until she meets someone she can trust. The other six were recently single, including one whose late husband had died of HIV-related complications. Among the other five, there were three disclosure-related break-ups. Single participants whose previous relationships had ended as a result of disclosure placed a primacy on acceptance in future relationships. One participant reported disclosing to her ex-boyfriend one month into their relationship; he left soon after. She expressed the view that young women should employ caution before disclosing, as men often end the relationship and/or tell others in the community. Another participant described how her husband, after testing HIV-positive, reacted angrily to learning that she was also living with HIV. He subjected her to verbal and physical abuse, cheated on her and ultimately left her for another woman.

Contraceptive use

When asked about contraceptive use, the majority of study participants identified condoms as their preferred type of contraception because condoms prevent both pregnancy and the acquisition and transmission of HIV and other sexually transmitted infections. A number of participants indicated a desire to use both condoms and a form of hormonal contraception (injection, implant or pills), but most of them had trouble negotiating this dual use. Most non-married participants with boyfriends reported condom use, regardless of whether or not they had disclosed their HIV status, while participants who were married or cohabiting reported less contraceptive use overall and rare use of condoms. Despite the expressed desire to control fertility through contraception, only about half of participants currently in relationships (11/21) reported using any form of contraception. Most participants reported that their boyfriends or husbands preferred not to use condoms.

“He would say, ‘I can’t use condoms, I’ve never used them before, I’m too old to learn now. If you don’t want to have sex with me, then get out of here.’” (Age 19)

In cases in which participants had disclosed to partners who reacted positively, condom use and dual contraceptive use were more common. Young women in these situations appeared to have better communication with their partners regarding sex in general; this encompassed comfort initiating sex and talking about which activities pleased them

HIV-positive mother of three. She is too ill to work and can only afford ARVs a few months of the year, Zimbabwe, 2008

A few married participants who had not disclosed described using hormonal contraception without their husband’s knowledge to prevent pregnancy. Long-term hormonal contraceptive methods, such as injections or implants, were the preferred methods in these cases.

Future childbearing plans and past childbearing experiences

Marriage and children figured prominently in study participants’ descriptions of their future aspirations. Whether currently married or not, participants’ desire for children was described within the context of supportive and committed relationships. Women who were not married described wanting to wait until they had settled down with a partner and achieved greater financial security before having children.

Most participants (21/28) had experienced at least one past pregnancy. Many of the children born to study participants had died, and most living children were still very young. Participants linked their desire to space pregnancies and to limit pregnancies to one or two children to perceived health risks during and after childbirth, as well as to past experiences with infant death. A few women who had not been on antiretroviral therapy at the time they gave birth fell ill following delivery, and almost half who had given birth had lost an infant before the baby’s second birthday (9/21). The following quote, from a participant who had lost two infants shortly after their births, illustrates the tension between fear and desire for a child expressed in many interviews:

“I did not expect my second child to die. So I’m now hesitant. I’m ambivalent because on the one hand I want to have another child, but on the other, I fear that I will have a child who will die like the others.” (Age 20)

“I just do not want to have sex with him yet, I am not in a rush to have sex… I don’t want to fall pregnant before he knows my [HIV] status. Even after we get married, I would like to go for some time, maybe even a year, without having a baby.” (Age 19)

In addition to challenges accessing PMTCT services at delivery, some participants reported having relatives, especially older relatives, disregard their plans for exclusive breastfeeding during the first six months, as recommended to reduce the risk of transmission of HIV from mother to child through breast milk. Because the norm in Shona culture is to begin mixed feeding with infants as young as one month of age, pressure or interference from others made it difficult for participants to fully implement best feeding practices.

“I decided to tell him [my partner] that I wanted to exclusively breastfeed our child for six months. However, my sister-in-law would take him and feed him foods like potatoes without my knowledge… My mother-in-law would lash out at me, saying that my child should be fed porridge.” (Age 20)

“I have not yet got what I want. I have been told only how to prevent transmission of HIV from the mother to the child, I have not yet been told about what to do when I want to get pregnant again.” (Age 19)

Partners: HIV testing and disclosure

Study participants described a close connection between disclosing their HIV status and engaging their partner in discussion about his HIV status or testing history. In all but one current or past relationship described, the young women were the ones to introduce the topic of HIV status and testing. One participant’s husband, who had since died from an HIV-related illness, found out he had HIV and encouraged her to get tested. Of the 12 participants who had disclosed to current partners, seven partners tested and five did not. Of the seven who tested, six are living with HIV.

The majority of participants underwent HIV testing before their partners did and reported difficulty in getting male partners to also test. Reasons that women perceived for their partners’ opposition included fear about results, denial of risk and a sense of fatalism. Partner resistance to testing is exemplified in the following quote.

“He says he will go for an HIV test one day, when he is ready… He tells me, ‘Either way, we are all going to die one day… Death is inevitable, whether one dies from AIDS or from an accident, it’s all the same.’” (Age 19)

The interview data suggest that men who reacted angrily or abusively when participants disclosed tended to have a lack of information about HIV and deep fear about their own HIV status. In a few relationships where sustained physical, verbal and sexual abuse followed the young women’s disclosure, the men had also tested HIV-positive and struggled with accepting their status, accusing the women of giving them HIV. In one case where a partner reacted abusively, the partner was hospitalized with illness and refused to share his HIV test results with the study participant.

Discussion

The young Zimbabwean women interviewed in this study described complex ways in which disclosure of HIV status factored into their ability to control fertility, particularly in relation to the tension between desire to limit, space and defer pregnancy as a health-promoting strategy and cultural norms that pressure women to bear multiple children soon after marriage. Findings suggest that disclosure has a profound effect on all components of decision-making surrounding the pregnancy process – motivation, knowledge, access and support. These results expand on previous research from similar epidemiologic contexts showing disclosure as central to safer sexual practices and successful implementation of PMTCT.Citation16–19

Regardless of their current relationship status, interview participants identified disclosure as a turning point in romantic partnerships, describing stressful experiences with major ramifications such as abuse and abandonment on the one hand, and support and love on the other. Most participants had disclosed to a previous or current partner, echoing findings showing high disclosure rates among women in Zimbabwe.Citation9 However, experiences following disclosure were not uniform. Participants saw open communication about their HIV status as the ideal, but those who had yet to disclose to current partners described anxiously weighing the risks and benefits as they strategized about when and how to share their status. Support from extended family helped some participants in relationships achieve ultimately positive outcomes following HIV disclosure.

Participants noted that health care providers could do more to help them navigate the disclosure decision-making process, beyond simply recommending that they tell their partners about their HIV status and bring them in for testing. Screening for the risk of violence and post-disclosure contingency planning could help young women make prepared and informed choices about disclosure. This conclusion fits with those drawn in similar epidemiologic settings, with other researchers calling for increased disclosure counseling for young women who test positive for HIV in the context of antenatal care.Citation16,20

Results, perhaps not surprisingly, highlight the central role that romantic partnerships play in the lives of young women, suggesting that HIV and reproductive health service providers must assume that young women living with HIV – whether married or unmarried– need access to comprehensive family planning services. While a quarter of study participants did not have a husband or boyfriend at the time they were interviewed, all but one participant had previously been in a relationship. All participants described raising children in the context of steady romantic partnerships as a future aspiration, noting that provider advice fell short of helping them achieve this goal. This finding is consistent with other research showing the inadequacy of family planning that focuses solely on long-term contraceptive methods for women living with HIV at the exclusion of discussing conception.Citation2,3 Study participants articulated a need for guidance on how to reduce the risk of transmission to partners with an unknown or HIV-negative status when they want to achieve pregnancy. Participants highlighted cost as a barrier to following provider advice to monitor viral load and CD4 count to gauge the optimal time to conceive. Cost was also a barrier to hospital delivery for some participants.

Since interviews in this qualitative study were conducted with a small, purposefully recruited sample, findings do not represent trends among the general population of young women living with HIV in Zimbabwe. Young unmarried women might not have felt comfortable discussing sexual activity and contraception, given cultural norms that sanction childbearing primarily in the context of marriage. Thus, the need for condoms and other family planning services might be greater than indicated in interviews. Given that we oversampled SHAZ!-Plus participants with a history of pregnancy, the proportion of young women who were currently or recently in committed relationships might be larger than in the overall population of young women living with HIV, which could mean that disclosure carried more weight for this study population. Interview questions exploring community norms attempted to address these potential limitations, contextualizing the personal stories of participants within the experiences of peers in their social and familial circles.

Conclusions

Our study suggests that HIV and sexual and reproductive health services have failed to respond to the complicated realities and conflicting pressures facing young women living with HIV in Chitungwiza, Zimbabwe, leaving them without adequate information or resources to control fertility and achieve optimum health outcomes for themselves and their children. The study population expressed a clear desire for spaced and limited pregnancy as a way to protect their health and plan for future healthy families. HIV and sexual and reproductive health services for young women in Chitungwiza and similar settings should consider comprehensive programs that better address the complexities of disclosure as it intersects with fertility control. To help young women utilize HIV prevention and treatment services, interventions should address social norms that stigmatize people living with HIV and their families, as fear of discrimination poses a barrier to accessing care and following precautions to reduce the risk of transmission to infants and partners.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the following colleagues for their essential contributions to this study: Olivia Chang, Wanzirai Makoni and Definite Nhamo.

References

- R Feldman, C Maposhere. Safer sex and reproductive choice: findings from ‘Positive Women: Voices and Choices’ in Zimbabwe. Reproductive Health Matters. 11(22): 2009; 162–173.

- K Johnson, P Akwara, S Rutstein. Fertility preferences and the need for contraception among women living with HIV: the basis for a joint action agenda. AIDS. 23(suppl 1): 2009; S7–S17.

- J Mantel, J Smit, Z Stein. The right to choose parenthood among HIV-infected women and men. Journal of Public Health Policy. 30(4): 2009; 367–378.

- J Forrest, A Kaida, J Dietrich. Perceptions of HIV and fertility among adolescents in Soweto, South Africa: Stigma and social barriers continue to hinder progress. AIDS and Behavior. 13(suppl 1): 2009; S55–S61.

- M McClellan, R Patel, G Kadzirange. Fertility desires and condom use among HIV-positive women at an antiretroviral roll-out program in Zimbabwe. African Journal of Reproductive Health. 14(2): 2010; 27–35.

- Central Statistical Office. Zimbabwe Demographic and Health Survey 2010. 2010; Macro International: Calverton, MD, USA.

- Population Council UNFPA. The adolescent experience in-depth: using data to identify and reach the most vulnerable young people: Zimbabwe 2005/06. The adolescent experience in-depth. 2009; UNFPA: New York.

- H Reynolds, J Kimani. An assessment of services for adolescents in prevention of mother-to-child transmission programs. 2006; Family Health International: Research Triangle Park, NC.

- R Patel, J Ratner, C Gore-Felton. HIV disclosure patterns, predictors and psychosocial correlates among HIV-positive women in Zimbabwe. AIDS Care. 24(3): 2012; 358–368.

- M Dunbar, K Maternowska, M Kang. Findings from SHAZ!: a feasibility study of microcredit and life skills HIV prevention intervention to reduce risk among adolescent female orphans in Zimbabwe. Journal of Prevention and Intervention in the Community. 38(2): 2010; 147–161.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Zimbabwe. Talk time I: HIV/AIDS in Zimbabwe today. 2003; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Harare, Zimbabwe.

- A Welbourn, A Williams, G Williams. Stepping Stones: a training package in HIV/AIDS, communication and relationship skills. 1995; ActionAid: London.

- Central Statistical Office. Population and Housing Census. 2002; Harare: Zimbabwe.

- C Charmaz. Constructing grounded theory: a practical guide through qualitative analysis. 2006; SAGE: London.

- K MacQueen, E McLella, K Kay. Codebook development for team-based qualitative analysis. Cultural Anthropology Methods. 10(2): 1998; 31–36.

- A Medley, C Garcia-Moreno, S McGill. Rates, barriers and outcomes of HIV serostatus disclosure among women in developing countries: implications for prevention of mother-to-child transmission programmes. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 82(4): 2004; 299–307.

- B Olley, S Seedat, D Stein. Self-disclosure of HIV serostatus in recently diagnosed patients in South Africa. African Journal of Reproductive Health. 8(2): 2004; 71–76.

- L Simbayi, S Malichman, A Strebel. Disclosure of HIV status to sex partners and sexual risk behaviors among HIV-positive men and women, Cape Town, South Africa. Sexually Transmitted Infections. 83: 2007; 29–33.

- C Farquhar, D Mbori-Ngacha, R Bosire. Partner notification by HIV-1 seropositive pregnant women: association with infant feeding decisions. AIDS. 15(6): 2001; 815–817.

- M Visser, S Neufeld, A de Villiers. To tell or not to tell: South African women’s disclosure of HIV status during pregnancy. AIDS Care. 20(9): 2008; 1138–1145.