This publication reports on a study conducted by the Women’s Program of the Asia Pacific Network of People Living with HIV (WAPN+),Citation1 together with the Regional Treatment Working Group, on positive women’s access to reproductive and maternal health care and services in six Asian countries: Bangladesh, Cambodia, India, Indonesia, Nepal, and Viet Nam. The objective of the study was to assess the experience of accessing reproductive and maternal health services as reported by HIV-positive women over 16 years of age and pregnant in the past 18 months.

The study used quantitative and qualitative methods and was conducted in three phases: a quantitative questionnaire among 757 women in the six selected countries, 17 in-depth interviews with women in Cambodia, India and Indonesia, and 10 focus group discussions (FGDs) with women in Bangladesh, Cambodia, Nepal and Viet Nam.

The findings provide a perspective into the social realities experienced by positive women and girls when trying to utilise reproductive and maternal health care services. The recommendations provide guidance on action to be taken in collaboration with governments, the health care sector, civil society and other partners, towards ensuring that national HIV policies and programs respond and protect the specific needs and rights of all positive women.

Background

Globally, an estimated 17 million women and girls were living with HIV in 2009 (nearly 52% of the estimated 33.3 million adults living with HIV), and more than two million pregnancies occur each year among HIV-positive women.Citation2,3 The HIV prevalence rate among women has increased since the early 1990s, partly due to increased HIV testing during pregnancy. In 2009, an estimated 370,000 children acquired HIV worldwide, a 24% drop compared to 2004 due to the increased access to services that support women to have HIV-free babies.Citation4

HIV testing among pregnant women is estimated to be at 42% coverage worldwide,Citation5 however some studies indicate that only 9% of pregnant women in Nepal were tested for HIV in 2009, and in Indonesia, less than 1%.Citation6,7 According to the World Health Organization (WHO), the main barrier to the expansion of HIV testing and counselling among pregnant women is the lack of access to antenatal care (ANC) services.Citation8 Factors influencing access include: i) knowledge and awareness; ii) distance to the health facility; iii) availability and cost (of transportation, services, laboratory tests, procedures, doctor fees, and medications); and iv) confidentiality and attitudes of healtcare providers.

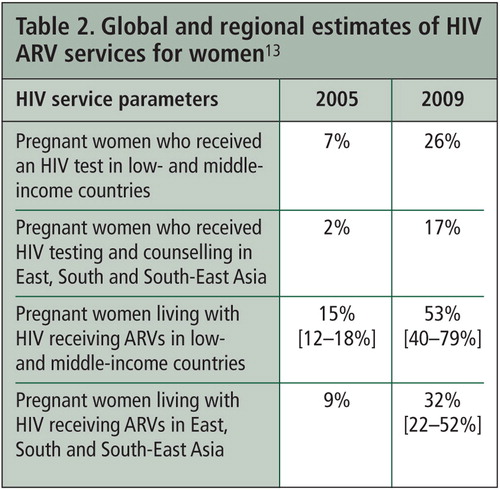

WHO estimated that in 2009, 45% of women and 37% of men in need of antiretrovirals (ARVs) received them.Citation10 A 2007 study from South-East Asia showed that more women than men received ARVs despite the fact that more men are living with HIV.Citation11 This is explained partly by earlier access by women to HIV testing during pregnancy, and prioritisation of mothers for treatment following the death of a husband or child. WHO reported an estimated 53% of pregnant women living with HIV received ARVs to reduce the risk of transmitting HIV to their infants in 2009, up from 15% in 2005.Citation12 In Asia, only 23,800 (32%) of the estimated 73,800 women in need of services to support them to have HIV-free babies received such care.

In the six countries covered in this study, there is limited overall progress in providing access to services to support women to have HIV-free babies. In 2009, 32.3% of positive pregnant women in Cambodia and Viet Nam received ARVs to reduce the risk of HIV transmission to their child, whereas India reportedly achieved lower than 17.4%, and Indonesia 3.8% and Nepal 3.3% (no data available for Bangladesh).Citation18–23

Survey findings

A total of 757 women were surveyed (Bangladesh 33, Cambodia 200, India 172, Indonesia 109, Nepal 40, Viet Nam 203). On average, the respondents were 29.3 years old (range: 17–47 years; standard deviation 5.4 years) and had one existing child (range: 0–8). The majority of respondents (77.2%) were currently married or living with a partner, 2.0% had never married or lived with a partner, and the remainder were widows or women no longer living with a partner. Overall 57.2% of respondents lived in urban settings and 42.8% lived in rural areas.

Half of all respondents (52.8%) depended on their family or members of their household for their main source of income, 37.3% had some form of independent income and 7.9% had no source of income. In Viet Nam substantially more respondents (46.5%) were self-employed than in other countries. Whilst the majority of women (70.9%) had either primary or secondary level education, 15.7% had never been to school. Respondents from Indonesia and Viet Nam spent the longest time in school (average 11.9 and 9.4 years), whereas the women from Nepal and Cambodia spent least time in school (average 3.3 and 3.4 years).

Most respondents were members of a PLHIV network (Bangladesh 97.0%, Cambodia 40.0%, India 43.0%, Indonesia 34.9%, Nepal 100%, Viet Nam 60.1%). More than half of the respondents (59.9%) joined before their most recent pregnancy, 22.2% during their pregnancy and 17.9% after their most recent pregnancy. On average, respondents had been diagnosed with HIV for a mean of 3.6 years (range: 0–18 years). The majority (56.3%) were diagnosed prior to their most recent pregnancy, 27.4% were diagnosed during pregnancy, and 9.9% after their most recent pregnancy. There were large variations between countries in terms of timing of HIV diagnosis. Cambodia recorded the highest percentage of women who knew their HIV status prior to their most recent pregnancy (82.5%) and India recorded the lowest (22.2%), with the majority of Indian women in the study (73.7%) learning of their HIV status during their most recent pregnancy.

Treatment

Women who tested positive at government facilities are usually referred to the nearest hospital that prescribes ARVs, and linked to outreach workers for follow-up, but women who test at private facilities rarely received counselling or referral.

Among the women surveyed, 485 (64.1%) were currently taking ARVs. The majority of women in all countries were on ARVs except in India where only 26.7% of respondents were. The average time since initiating ARVs was 27 months (Bangladesh 43 months, Cambodia 19, India 5, Indonesia 30, Nepal 30, Viet Nam 34). The longest time any respondent had been on ARVs was 141 months (almost 12 years). Among 338 respondents who gave details of when they initiated ARVs in relation to their pregnancies, a minority (41.2%) reported initiating ARVs before their current pregnancy, 50.9% during their pregnancy and 7.9% at the point of delivery. Of the 338 women who received ARVs during pregnancy, 113 women (33.0%) admitted having difficulties staying on the ARV regimen. The main reasons women faced difficulties were side effects (85.7%), fear for baby (68.1%), illness (68.1%) and inability to access the clinic (53.8%). Some women in FGDs said they received very little information and many were afraid ARVs might harm their infant.

Of the women not currently on ARVs, 61 women reported having initiated ARVs previously either during the pregnancy (43 women) or at the point of delivery (18 women) for the purpose of preventing HIV transmission to their unborn infant. Of those not on ARVs and who delivered, all were given a single dose of nevirapine when labour began. Following delivery, these women were taken off ARVs by their doctor or they stopped due to transportation and other costs. One woman in Indonesia said she was ineligible for free ARVs because she was not legally married, and as she could not afford to buy ARVs, she did not take any during her most recent pregnancy.

In interviews, several reasons were cited for discontinuing treatment, not adhering to regimens, or not seeking ARVs, including: i) cost (of transportation, administration and doctor’s fees, laboratory tests, procedures); ii) adverse side effects; and iii) stock-out of drugs or expired drugs. One interviewee said that some women feel better after taking their medicine, and think they are cured, so they stop taking it. Some women have never had a CD4 count to monitor their HIV progression and have never discussed ARVs with their doctor. Although ARVs are free in Cambodia, women have to visit the clinic several times before they are put on treatment in order to demonstrate they are capable of adherence and somebody is committed to helping them. One woman who has had no medical check-up since her diagnosis three years earlier and does not know her CD4 count said it is too expensive to pay for the transport as well as the doctor’s visit (US$ 2).

Many women said that the biggest challenge to staying on treatment is finding the money to cover transportation expenses. Every month most women must travel to their ARV centre to get their ARVs but often they do not have enough money for transport. One Indonesian woman said it costs her one-eighth of her monthly income to travel to the government hospital. Many women have to borrow money to make the trip.

Contraception

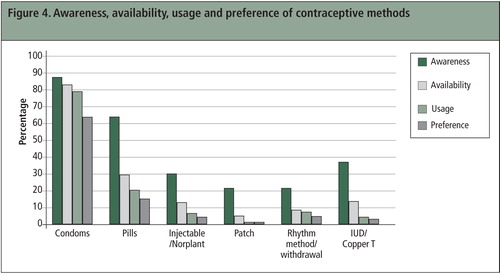

Condoms were the most known (88.1%), available (83.4%), used (79.3%) and preferred (63.9%) method of contraception, followed by oral pills. Preference for condoms ranged from 48.6% in Indonesia to 80.0% in Nepal. Bangladesh showed the highest preference for pills (36.4%), compared to just 2.5% in Nepal. The use of injectables was not a preferred option for any respondents in India, yet in Indonesia 22.9% indicated preference for this method. Awareness of intrauterine device (IUD) was 38.2%, but their availability, usage and preference were substantially lower: IUD was not a preferred option (0%) in Bangladesh, Cambodia or Nepal, but was preferred by 8.3% Indonesia and 8.7% of women in India. Four respondents could not name any method to prevent pregnancy.

Despite the stated preference for condoms in the survey, they are not used consistently. The major reason given was because the woman’s partner makes decisions on condom use (Bangladesh 36.4%, Cambodia 63.0%, India 39.5%, Indonesia 23.9%, Nepal 7.0%, Viet Nam 19.2%). Women in interviews and FGDs said consistent condom use was very difficult because i) their partners object to condoms and complain that they do not enjoy sex with them, ii) they find them inconvenient or iii) they cannot afford them. The need to counsel couples together about consistent condom use was raised by several women in different countries.

While most women said they preferred condoms for prevention of STIs, to prevent pregnancies, they want family planning methods that they can control – IUDs, birth control pills or injectables. Women were not asked in the survey whether they used microbicides, female condoms or sterilisation as a form of contraception; however, some women in the qualitative part of the study indicated that they opted for tubal ligation to avoid pregnancy. Women who were sterilised said they now found it more difficult to convince their husbands or partners to use condoms.

Many women said that 100% condom use is the only contraceptive option promoted amongst positive women, including with sero-concordant couples, because health care workers do not want them to spread the virus. Women are advised to use condoms exclusively to avoid cross-infection of a different strain of HIV. Women in FGDs in Viet Nam said they would like better access to female condoms which are not readily available and suggested promoting female condoms.

The persons who respondents were most likely to approach for advice on reproductive and maternal health options were medical practitioners, with half of the respondents seeking support from them. Although fewer women (23.0%) sought help from support groups, they were viewed as most supportive. Only 64.2% of respondents sought advice or counselling (usually from a facility-based medical practitioner) regarding reproductive health options prior to their most recent pregnancy (Bangladesh 57.6%, Cambodia 78.0%, India 76.2%, Indonesia 67.9%, Nepal 35.0%, Viet Nam 44.8%). In Cambodia, 46.0% of respondents also sought advice from their peer support group. For most poor women, interactions with the health system were limited to their HIV care and treatment, and during pregnancy. Opportunities for counselling on family planning were few. Women interviewed did not have much information on pregnancy prevention or birth spacing, and family planning is a topic few women are comfortable to raise with their (mostly male) HIV doctors. Amongst those who did raise issues about their sexual and reproductive health, responses from their doctors varied, but often they discouraged further discussion. Several women chose to seek sexual and reproductive health care services at private or NGO-sponsored clinics, sometimes without disclosing their HIV status for fear of discrimination.

Pregnancy outcomes

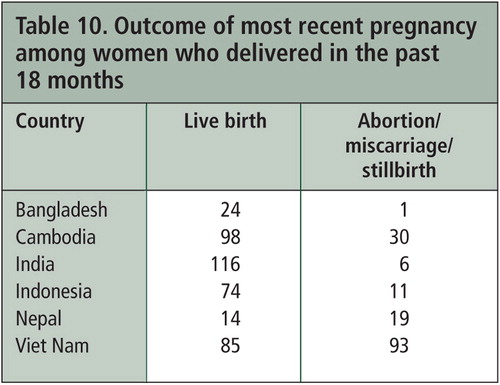

Of the 757 survey respondents, 186 women (24.6%) were still pregnant at the time of the survey. Among the remainder who were pregnant in the past 18 months but were not currently pregnant, 72.0% had live births and 28.0% had either an abortion, miscarried or had a stillbirth.

It was rare for women in most countries to find supportive health care workers during their pregnancy. In Cambodia and Viet Nam, some women who were determined to have a child educated themselves about current HIV science, and discovered supportive doctors within the public health system.

However, most women in FGDs and interviews said they were discouraged by health care workers from becoming pregnant. Doctors were often unsupportive and proffered a range of reasons for discontinuing a pregnancy, including: the baby may be positive, the baby may be orphaned, pregnancy may weaken the woman’s health, the woman has a poor economic situation, older women shouldn’t have a baby, the woman already has children.

Of women surveyed, 26.6% said their pregnancy was unplanned. Planned pregnancies were usually first pregnancies, or first pregnancies with a new husband or partner. Overall, 37.1% of women reported their most recent pregnancy as unwanted (Bangladesh 33.3%, Cambodia 43.5%, India 10.3%, Indonesia 33.0%, Nepal 47.5%, Viet Nam 53.2%). There was no significant relationship between knowing HIV status before pregnancy and wanting the pregnancy, but whether or not the woman was currently living with a partner was significantly related to whether the pregnancy was wanted. Several Cambodian women said that it was their husbands, not them, who wanted the pregnancy.

Less than half (44.8%) of respondents reported that decisions regarding their pregnancy were made together with their husband or partner; in 21.0% of cases, the man alone made the decisions; and in 10.6% of cases, the woman alone made the decision. Indonesia, Nepal and Viet Nam had substantially more women as sole decision-makers (range: 12.8% to 19.2%) compared to Bangladesh, Cambodia and India (range 3.0% to 6.4%).

Overall 70 women (9.2%; range: Nepal 2.5% to India 16.9%) said their mother or mother-in-law was also involved in decisions around pregnancy. In-laws often pressurise a woman to have a child, especially if she has no son. This can be very difficult if the woman has not disclosed her HIV status or if she has been sterilised. In Nepal, some women consequently screen their pregnancies and if it is a girl, have an abortion.

In total, nine women (1.2% of all respondents) had stillbirths. In Nepal, the number of miscarriages was considerable with eight of the eighteen pregnancies resulting in miscarriage, the highest number in one of the smallest samples. Women in the Nepal FGDs did not consider that this rate of spontaneous miscarriage was particularly high compared with the general population.

Abortion

Among the 573 respondents who had been pregnant in the previous 18 months and were no longer pregnant, 125 (21.8%) reported that they had an abortion. There is wide variation in the proportion of pregnancies that resulted in abortion, from Bangladesh and India 0–1%, Indonesia 8.3%, Cambodia 11.5%, Nepal 25.0%, to Viet Nam 43.9%.

Whether a woman’s pregnancy was aborted directly correlated with whether the pregnancy was wanted. Nevertheless, among the women who had abortions, 29.4% said the pregnancy had been wanted.

Reasons for having an abortion included poor economic situation, fear of infecting the baby, and the pregnancy being unplanned; 60.0% of women reported that the abortion occurred specifically because of their HIV status. Many Vietnamese women in FGDs said they had an abortion because they assumed or were told that the baby would be HIV-positive or their health status was too weak. Some said doctors often say the pregnancy is not normal after the ultrasound. One woman was advised to have an abortion just before the delivery.

Many women were asked to consider abortion either by health personnel and/or by their family members. In the majority of cases women said that the decision to have an abortion was made by themselves, although sometimes it was made by their husbands.

Many women who were urged to have an abortion faced discrimination when they had the procedure. Some women had to pay higher fees than HIV-negative women paid. Other women were made to wait until the end of the day when all procedures among HIV-negative women were completed. Some women who had a medical rather than a surgical abortion suffered severe pain and blood loss as a result.

“When I went for the abortion I had to wait for all the negative women to go first. They used three pairs of gloves and covered all their body with plastic, like a raincoat, and they wore glasses because they were afraid.” (Hong, Viet Nam)

One woman tried to use traditional medicine to induce an abortion because she was afraid of the stigma she might face if she went to the hospital. She began to haemorrhage and was forced to go to the hospital where she faced lots of discrimination from the doctor.

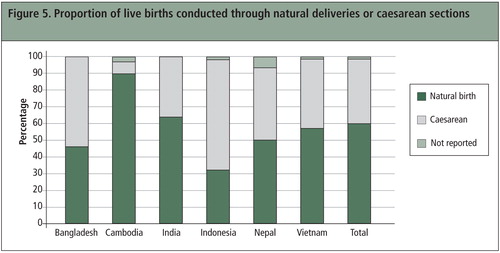

Delivery

Of 420 women who had delivered by the time of the study, 63.1% had vaginal deliveries and 36.8% were by caesarean section. The proportion of caesarean sections varied considerably between countries: Cambodia 7.1%, Nepal 33.3%, India 35.8%, Viet Nam 41.4%, Bangladesh 56.5% and Indonesia 67.1%. There was no relationship between length of time women had been on ARVs and type of delivery.

Proportionately more women who knew their HIV status delivered at government health care facilities (84.7% versus 71.1%), except in Bangladesh where all women surveyed delivered at an NGO clinic. Among women who did not know their HIV status, there were three times as many home deliveries (29 in total). Women in rural areas who knew their status usually travelled to an urban area for the delivery. In the FGDs and interviews extreme instances of discrimination at the time of the delivery were cited by women in all countries except Bangladesh. Many women recounted their experiences of being completely neglected by staff before, during and after their delivery, or of staff abusing the woman for getting pregnant when she was in the throes of labour pains. Women were left alone in labour, and often staff refused to touch them or bathe their newborn infant. Women recounted stories of them or their mother or husband having to bathe the newborn infant, and one incident where the woman’s mother was made to wash the blood off the floor after the delivery. Most women in Viet Nam are put in separate rooms and isolated during delivery, and must pay the cost of the private room.

Caesarean section

Many women in all countries except Cambodia said they were rarely given the option to have a vaginal delivery if their HIV status was known. Many women believe it is necessary to have a caesarean. In Viet Nam women said it is government policy for HIV-positive women to have a caesarean delivery, but often it is difficult to find doctors willing to perform the operation because they are afraid of HIV. Some women did not reveal their HIV status to their gynaecologist in order to avoid what they perceived to be a mandatory referral for a caesarean delivery. In Indonesia, the cost of a caesarean section is prohibitively expensive for many women.

Sterilisation

Of the women surveyed, 228 (30.1%) said they were asked or encouraged to consider sterilisation. Of these, 140 (61.4%) felt they were given the freedom to decline and 86 women (37.7%) said they did not have the option to decline. Women in Cambodia, India, and Indonesia recorded the highest rate of being asked to undergo sterilisation (over 35%). Indonesian women recorded the highest proportion who were given the option to decline the procedure (39 of 44 women) whereas Cambodian women recorded the least choice to decline sterilisation (34 of 70 women).

Women who were urged to undergo sterilisation tended to have more children (average two) than other women, however, 4.6% of those encouraged to undergo sterilisation did not have any children. Where women resided, their education level, or their age had no significant relationship to recommendations for sterilisation. There was, however, a significant relationship between whether a woman had a caesarean section and whether she was encouraged to be sterilised; 43.5% of women who gave birth by caesarean section were encouraged to be sterilised compared to 29.9% of women who had vaginal deliveries.

The majority of recommendations for sterilisation (61.4%) came from gynaecologists and HIV clinicians, and most respondents (82.6%) believe that the recommendation was made on the basis of their HIV-positive status. Doctors offer a range of reasons for sterilisation, despite the fact that the risk of infants becoming HIV-infected is very low if women are on ARVs. In 9.6% of cases outreach workers, and in another 9.6% of cases family members made the recommendation for sterilisation, in 4.6% of cases the husband or partner recommended it, and in only 2.8% of cases was it the woman’s own suggestion. One woman who was coerced into being sterilised at the time of delivery said her child died one month after birth. In some cases, women did not know whether they were sterilised during their caesarean. At least one woman had been sterilised without her consent.

In India, some women said that often women and their families did not understand what sterilisation was, and thought it meant a more “sterile” delivery, to which families eagerly agreed. Additionally, where the choice to be sterilised was available, several women indicated they did not have the power themselves to refuse or to accept, either because their health decisions were made by their husbands, partners, or family members, or (in the case that they wanted to be sterilised) the hospital required spousal consent. In some places, while the choice was left to the woman, incentives were offered such as free formula milk, which many poor women could not pass up. In Indonesia, sterilisation is actively encouraged as a family planning method, not just for positive women, and is offered free at the time of both natural and caesarean delivery; only occasionally do doctors discourage positive women from getting sterilised either because they are too young or because it may negatively affect the woman’s health.

In the FGDs only one woman said her partner had been encouraged to have a vasectomy.

“At the hospital, staff told my husband that if he had a vasectomy they would give him 2000 taka [US$ 25] and new clothes but he refused.” (Kabita, Bangladesh)

“Men should have a vasectomy because it is more of a burden on women, but none of them do.” (Sreymom, Cambodia)

Maternal health care

Most women (80.9%) received some form of maternal health services during pregnancy, although 12.4% did not receive any services despite seeking them, and 5.5% did not seek maternal health services. Most respondents (57.9%) sought maternal health services by the second month of their pregnancy in all countries except Bangladesh, where only 32.3% sought maternal care that early in their pregnancy; a small proportion of respondents (2.1%) did not seek services until their eighth or ninth month of pregnancy. Of the women who did seek services, 62.7% had more than three antenatal check-ups. There was a strong correlation between receiving care and having a live birth; 47.3% of pregnancies to women who sought pregnancy-related health care but did not receive it resulted in miscarriage or abortion. In all countries except Bangladesh, a majority of women reported obtaining maternal health care services from government centres in urban areas (69.2% overall). Most respondents from Bangladesh obtained services from a non-government health care centre and eight women delivered at home.

Services women received include: ultrasound (68.5%); gynaecological counselling and testing (60.9%); vitamins (56.3%); blood tests (53.7%); obstetric care and delivery (51.7%); feeding and nutrition counselling (47.3%); immunisation (37.7%); STI counselling and testing (32.7%); internal examinations (21.7%). A majority of women in all countries except India and Nepal had an ultrasound. In Viet Nam, only 7.9% of women received an internal examination.

Several women spoke of discrimination from health care workers if they disclosed their status, particularly from nursing staff and obtetricians and gynaecologists. In several countries, women complained of health care workers breaching confidentiality with negative consequences. Some health care workers asked questions such as, “How did you get HIV?” and “Why did you get pregnant?” in front of other patients in the ward. One woman had to move house because an outreach worker who came to visit her told the head of the local authority that she had HIV and he told all her neighbours. Women in Cambodia, Indonesia, Nepal and Viet Nam said they are often made to wait until last to see a doctor for any procedure, even an ultrasound, regardless of how early they arrive at the centre. Women in Nepal said that when doctors do treat them, they put on three or four pairs of gloves. One woman in Nepal, who had had a caesarean, was left to do everything by herself and in the process tore her stitches and was then chastised by the doctor for being careless and had to wait two days to get new stitches.

Integration of services

Overall, 61.0% of survey respondents reported that they could access HIV, reproductive, maternal, and childcare services at the same government facility. This excluded Bangladesh, which did not report access to a government hospital. India had the highest percentage of women reporting integrated health care services from government hospitals (82.6%), followed by Indonesia (79.8%). Indian women were also most satisfied with the level of confidentiality afforded them (87.2%) and with the overall maternal health care provided to them. In the survey, 57.7% of women said confidentiality could be better maintained in an integrated health care setting.

In Cambodian FGDs, several women complained that, for a single ANC visit, they were required to travel to different locations with referral slips for ultrasound and laboratory testing, often consuming an entire day for each visit, and discouraging them from seeking continued care. In Nepal women said they are shunted from one hospital that provides ARVs to another that provides maternal health care, and are constantly referred around in circles because nobody wants to deal with a positive woman who has a pregnancy. Ultimately this results in some women not disclosing their status in maternal health care settings. Consequently, the sexual and reproductive health of HIV-positive women is often neglected in this loop. Many women said they would utilise health care services more regularly if they were integrated within the same government health care facility.

Only about one in four women had ever had a pap smear (28.9%). Most women had no idea why it is important for HIV-positive women to have regular pap smears, and many only realised they had had one once the procedure was explained.

In the survey, 291 respondents (41.6%) reported having difficulties finding a gynaecologist to care for them during their pregnancy due to their HIV-positive status. In Cambodia, 69.0% of women said there was communication between their HIV doctor and their gynaecologist about their delivery but in Viet Nam only 7.9% of women said this was the case. Many women interviewed said they want advice about how to get pregnant safely and how to deliver a healthy baby but they do not know where to seek advice because so many HIV doctors are unsupportive of positive women’s desire to have children. Without access to information through the health care system, many women rely on friends for advice on decision-making about their health.

Key recommendations

Invest in positive women’s organisations

| • | Increase capacity of HIV-positive women’s organisations to respond to their needs | ||||

| • | Train positive women and their partners at national, provincial and local level about their sexual and reproductive health and rights and increase positive women’s capacity in decision-making | ||||

| • | Facilitate positive women’s capacity to advocate for their rights to sexual, reproductive and maternal health care services | ||||

Expand counselling

| • | Train and employ HIV-positive women as counsellors at all government testing centres | ||||

| • | Expand HIV counselling beyond post-test to include psycho-social/emotional support, ARV treatment, SRHR advice and support; consider couple and family counselling when women do not have decision-making authority; strengthen referral systems to health care services | ||||

Uphold positive women’s rights

| • | Ensure governments fulfil their obligations to protect HIV-positive women’s rights according to international treaties | ||||

| • | Ensure no woman is coerced into testing, abortion, sterilisation, caesarean | ||||

| • | Ensure HIV-positive women have access to a range of contraceptive options that they can control, to avoid unwanted pregnancies | ||||

| • | Ensure WHO Guidelines on ARVs are adopted | ||||

| • | Ensure no positive woman experiences discrimination within the health sector | ||||

| • | Train obstetric and gynaecological service providers to be sensitive to the needs and rights of HIV-positive pregnant women; include training on quality of care and positive women’s sexual and reproductive health and rights in clinical management and curriculum training of health care workers | ||||

| • | Integrate services to improve access, utilisation and follow-up, and reduce discrimination | ||||

Expand social security

| • | Review national guidelines for social services requirements and expand social welfare and nutritional support for positive women and children | ||||

| • | Provide transport subsidy for mothers on low income to attend ARV centres | ||||

| • | Improve HIV-positive women’s income generation capacity. | ||||

Acknowledgements

This is an excerpted version of this publication and is reprinted with the kind permission of the Women’s Program, Asia Pacific Network of People Living with HIV (WAPN+), who retain the copyright. They can be contacted through: http://www.apnplus.org/. Extensive quotes from study participants, information about women’s babies and references not pertaining to the text here were excluded due to space limitations. The full text and references can be found at: http://www.eptctasiapacific.org/documents/positive_and_pregnant_2012_apnplus_0.pdf.

References

- Asia Pacific Network of People Living with HIV (APN+), 2010. “Women of Asia Pacific Network of People Living with HIV”. At: http://www.apnplus.org/main/Index.php?module=project&project_id=3

- UNAIDS. Global Report: UNAIDS Report on the Global AIDS Epidemic, 2010. 2010; UNAIDS: Geneva.

- J McIntyre. Maternal health and HIV. Reproductive Health Matters. 13(25): 2005; 129–135.

- Ibid.

- WHO. Towards Universal Access: scaling up priority HIV/AIDS interventions in the health sector (Annex 5). 2010; WHO: Geneva.

- Government of Nepal, Ministry of Health and Population. 2010; UNGASS Country Progress Report: Nepal.

- National AIDS Commission Indonesia, Republic of Indonesia – Country Report on the Follow up to the Declaration of Commitment on HIV/AIDS (UNGASS): Reporting Period 2008–2009. 2009, National AIDS Commission Republic of Indonesia.

- WHO Regional Office for South-East Asia. HIV/AIDS in the South-East Asia Region: Progress report 2010. 2010; World Health Organization.

- WHO. Women and Health: Today’s Evidence, Tomorrow’s Agenda. 2009; World Health Organization.

- S Le Coeur, IJ Collins, J Pannetier. Gender and access to HIV testing and antiretroviral treatments in Thailand: Why do women have more and earlier access?. Social Science and Medicine. 69: 2009; 846–853.

- WHO. Scaling up HIV services for women and children. Chapter in Towards Universal Access: Scaling up priority HIV/AIDS interventions in the health sector. 2010 Progress Report. 2010

- WHO. Scaling up HIV services for women and children. Chapter in Towards Universal Access: Scaling up priority HIV/AIDS interventions in the health sector. 2010 Progress Report. 2010

- Data not available for Bangladesh.

- National AIDS Authority, Cambodia Country Progress Report: Monitoring the Progress towards the Implementation of the Declaration of Commitment on HIV and AIDS – Reporting period January 2008 – December 2009. 2010.

- National AIDS Control Organisation, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India, Country Progress Report: Reporting Period – January 2008 to December 2009, India.

- National AIDS Commission Indonesia, Republic of Indonesia – Country Report on the Follow up to the Declaration of Commitment on HIV/AIDS (UNGASS): Reporting Period 2008–2009. 2009, National AIDS Commission Republic of Indonesia.

- Government of Nepal, Ministry of Health and Population, UNGASS Country Progress Report Nepal 2010.

- The Socialist Republic of Viet Nam, UNGASS Country Progress Report: Reporting period January 2008 – December 2009. 2010: Hanoi.