Abstract

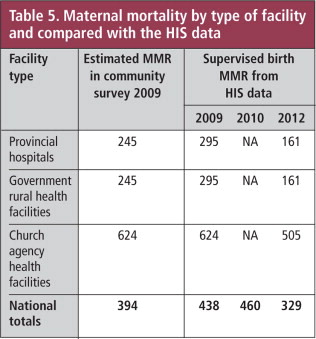

Over the past 30 years maternal mortality estimates for Papua New Guinea have varied widely. There is no mandatory vital registration in PNG, and 85% of the population live in rural areas with limited or no access to health services. Demographic Health Survey data for PNG estimates the maternal mortality ratio to be 370 deaths per 100,000 live births in 1996 and 733 in 2006, whereas estimates based upon mathematical models (as calculated by international bodies) gave figures of 930 for 1980 and 230 for 2010. This disparity has been a source of considerable confusion for health workers, policy makers and development partners. In this study, we compared 2009 facility-based survey data with figures from the national Health Information System records. The comparison revealed similar maternal mortality ratios: for provincial hospitals (245 and 295), government health centres (574 and 386), church agency health centres (624 and 624), and nationally (394 and 438). Synthesizing these estimates for supervised births in facilities and data on unsupervised births from a community-based survey in one province indicates a national MMR of about 500. Knowing the maternal mortality ratio is a necessary starting point for working out how to reduce it.

Résumé

Ces 30 dernières années, les estimations de la mortalité maternelle pour la Papouasie-Nouvelle-Guinée ont beaucoup varié. Le pays n’a pas d’enregistrement obligatoire à l’état civil et 85% de la population vit dans des zones rurales avec un accès limité ou inexistant aux services de santé. Les Enquêtes Démographiques et de Santé ont évalué le taux de mortalité maternelle à 370 décès pour 100 000 naissances vivantes en 1996 et 733 en 2006, alors que les estimations fondées sur les modèles mathématiques (utilisés par les institutions internationales) aboutissent à 930 pour 1980 et 230 pour 2010. Cette disparité est une source de confusion considérable pour les agents de santé, les décideurs et les partenaires du développement. Dans cette étude, nous avons comparé les données d’une enquête de 2009 réalisée dans des centres de santé avec les chiffres du système national d’information sanitaire. La comparaison a révélé des taux similaires de mortalité maternelle : pour les hôpitaux provinciaux (245 et 295), les centres de santé publics (574 et 386), les centres de santé des institutions religieuses (624 et 624) et au niveau national (394 et 438). La synthèse de ces estimations pour les accouchements assistés dans les maternités et les données sur les accouchements non assistés provenant d’une enquête communautaire dans une province indique un taux national d’environ 500. Connaître le taux de mortalité maternelle est un point de départ nécessaire pour trouver les moyens de le réduire.

Resumen

En los últimos 30 años las estimaciones de mortalidad materna en Papua Nueva Guinea han variado considerablemente. En PNG, no hay registro obligatorio de estadísticas vitales y el 85% de la población vive en zonas rurales con limitado o ningún acceso a servicios de salud. Las Encuestas Demografícas y de Salud de PNG calcularon que la razón de mortalidad materna en 1996 era de 370 muertes por cada 100,000 nacidos vivos y 733 en 2006, mientras que las estimaciones basadas en modelos matemáticos (calculadas por organismos internacionales) dieron cifras de 930 en 1980 y 230 en 2010. Esta disparidad ha sido una fuente de considerable confusión para profesionales de la salud, formuladores de políticas y socios en desarrollo. En este estudio, comparamos datos de encuestas realizadas en 2009 en unidades de salud con cifras de los registros del Sistema Nacional de Información en Salud. La comparación reveló similares razones de mortalidad materna: para hospitales provinciales (245 y 295), centros de salud gubernamentales (574 y 386), centros de salud de instituciones eclesiásticas (624 y 624) y nacionales (394 y 438). La síntesis de estas estimacions para partos supervisados en unidades de salud y datos de partos no supervisados de una encuesta comunitaria en una provincia, indica una RMM nacional de aproximadamente 500. Conocer la razón de mortalidad materna es un punto de partida necesario para determinar cómo reducirla.

Maternal mortality ratio (MMR) estimates for Papua New Guinea (PNG) have varied widely over the past 30 years. Although there is little vital registration of births and deaths in PNG, there have been a number of national and sub-national household surveys, and since 1978 health workers have been encouraged to report all maternal deaths on a special form to a national maternal mortality registry alongside the Health Ministry’s National Health Information system (HIS) reporting.

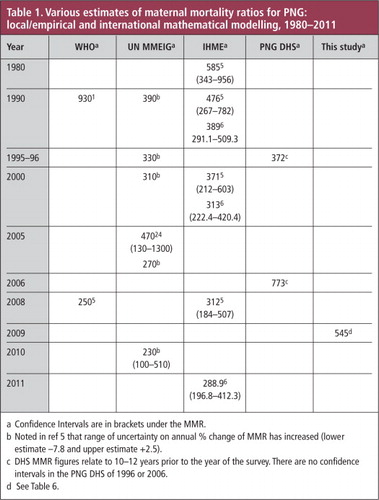

In the 1990s the World Health Organization, using a mathematical model, estimated that the MMR for PNG was 930/100,000 live births.Citation1 Since then all internationally derived MMR figures for PNG have put the MMR substantially lower than local (empirical) estimates. Table 1 summarizes the MMR estimates for PNG from all sources from 1980 to 2011. UN trend data published in 2012 put the MMR for 1990 at 390, falling to 230 in 2010.Citation2 PNG Demographic Health Survey (DHS) calculations (using the indirect sisterhood method) put the figure at 372 in 1996Citation3 and 733 in 2006.Citation4 In 2010, the maternal mortality estimates from the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME), Seattle, USA,Citation2 were published. The IHME estimated MMRs for Papua New Guinea for four time periods, (confidence intervals in brackets): 1980, 585 (343–956); 1990, 476 (267–782); 2000, 371 (212–603); and 2008, 312 (184–507). There has been a further revision of the IHME estimates in 2011.Citation5

The IHME uses the following independent variables in their mathematical modelling to estimate the MMR: total fertility rate (TFR), gross national income (GNI) per capita, neonatal mortality rate, HIV seroprevalence, skilled birth attendance rate and age-specific female education (with five-year stratification) for the reproductive ages 15–45 years. Data for neonatal mortality, total fertility rate and skilled birth attendance are usually generated through donor-sponsored Demographic Health Surveys,Footnote* or UNICEF-sponsored Multiple Indicator Cluster Surveys (MICS). The UN Maternal Mortality International Estimates Group (MMIEG) analysis uses GDP per capita, general fertility rate and skilled birth attendance rate. In a recent review article on interpreting international estimates of maternal mortality AbouZahr reports that the authors of both the IHME and UN MMEIG consider the GNI/GDP per capita to be “the most important driver of MMR trends…”.Citation6

Although PNG does not have complete and reliable data on maternal mortality, some empirical data are available from local studies and from the national Health Information System. Maternal mortality was also derived from the PNG DHS conducted in 1996 and 2006. These figures are substantially different from those estimated by international groups, giving rise to confusion among PNG’s health workers, national leaders, policy makers and development partners about what the actual maternal mortality might really be. Is the trend up or down? What is really needed to achieve MDG 5 and improve pregnancy outcomes for PNG women?

When the PNG DHS 2006 MMR figure of 733 was published, the Minister for Health declared maternal mortality to be a national health emergency and set up a task force to investigate the issue and make recommendations on how to address the problem. The task force reported in 2009.Citation7 An emergency response team was set up in 2010 and PNG’s donors (UN agencies, NZAid and AusAid) allocated a great deal of money to the effort. Unfortunately, later the same year, before any substantive action had been taken on the recommendations of the task force, the MMEIG group issued estimates of maternal mortality in PNG of 230 (100–510).Citation8 In 2011, the IHME estimated the PNG MMR to be 289 (196.8-412.3).Citation5 (see Table 1) Responding to queries about the discrepancies between the local and international estimates has been a distraction to the members of the response group, who are trying to get on with the job of implementing strategies to reduce maternal deaths.

The two collaborative global series of model-derived estimates (both claiming to be based on systematic reviews of all available data) were for similar time periods: IHME for the period 1980–2011 and UN-MMEIG for 1990–2010. Both produced estimates that were substantially lower than in-country empirical estimates. The MMEIG and IHME did not take all local (empirical) data into account for technical reasons. For example, data using the indirect sisterhood method were not used because they relate to a period some 10–12 years prior to the actual survey and have very wide confidence intervals. The MMEIG use only national level data and so exclude data from the National Health Information System that covers facility deaths and does not include deaths that occur in the community. The IHME use sub-national data only if they meet stringent technical criteria. Moreover, there were known problems with sampling in the PNG DHS surveys. One analysis of the 2006 DHS found that “younger females were over-sampled while older women were under-sampled”.Citation9

These uncertainties are hampering efforts in PNG to address the problem of maternal mortality. In an attempt to supplement the empirical MMR estimates in PNG, we conducted a facility-based audit of maternal deaths for the year 2009, reviewed HIS data for 2009–2012 and compared the figures with the findings of a community-based survey of maternal deaths in one province for the same year.Citation10

Methodology

Information about supervised births and maternal deaths that occurred in facilities was obtained by three separate pathways. In 2010, all health facilities that offer supervised birth were surveyed by letter, fax and email and followed up where possible by telephone. They were asked to provide the numbers of supervised births and maternal deaths that had occurred within their facility during 2009. During 2011 and 2012 one author (GM) visited 10 provinces and was able to check data in the local provincial hospital and rural health data in the provincial health office.

The Health Information System (HIS) data from the National Department of Health were analyzed by facility for supervised births. All facilities authorized to care for maternity cases are required to report data to the national HIS hub on a monthly basis: if a facility fails to report during a given period, this is recorded and attempts are made by the national HIS team to acquire the missing data. In 2009, the HIS reporting rate from hospitals was 100% and for health centres 88%.Footnote* However, there are no patient identification data given by facility HIS officers, and so it is not possible to cross check HIS maternal death counts with data from the national maternal mortality registry, or data on maternal deaths reported by clinicians to the Obstetrics & Gynecology Society.Footnote† Allowances for incomplete monthly reporting were made by extrapolating the data for 12 months from the number of months that were reported.

In PNG private birthing facilities are available only in the national capital. From an estimated 15,000 births in Port Moresby, only about 1100 occur in private facilities and 12,000 in the one public maternity hospital; the remainder occur at home. Only one maternal death occurred in the private hospitals in Port Moresby during 2009.

Maternal mortality reports are made each year by midwives and doctors who work in maternity care to the Annual General Meeting of the PNG Society of Obstetrics & Gynecology; figures for 2009 were reported at the 2010 AGM. In 2010, 14 of the 20 provinces reported their 2009 statistics to the Society meetingFootnote*; the lead author (GM) personally followed up the remaining six provincial hospitals to verify total births and maternal deaths for that year.

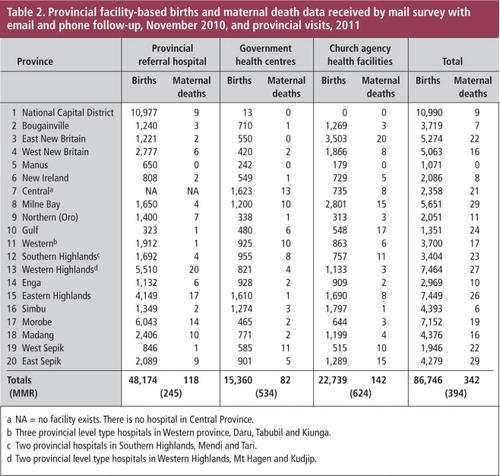

Information from the facility-based survey and the Society of Obstetrics & Gynecology records are summarized in Table 2. Information from the HIS data bank is shown in Table 3. In the analysis of facility-based maternal deaths, when there was a discrepancy between the HIS data and that provided by reporting clinicians to the O&G Society AGM, the latter was taken as more accurate if it could be verified by personal check of facility records.Footnote† Otherwise, the HIS data were accepted.

All rural health facilities have a Health Information System officer whose job is to report all facility births and deaths to the national HIS hub on a monthly basis. In this way it is possible to monitor completeness of reporting by province and facility. During the study the HIS count of rural facility maternal deaths was consistently more than the numbers reported to the Maternal Death Registry, whereas there appeared to be a deficit of maternal deaths in the HIS count from provincial hospitals. During cross-checking of HIS and provincial hospital data, an under-counting of births and maternal deaths was found in 50% of the provincial hospitals. This appeared to be due to poor internal communications between maternity staff and the hospital HIS officer, who usually sits in an office some distance away and does not physically visit the maternity section to check their registers.

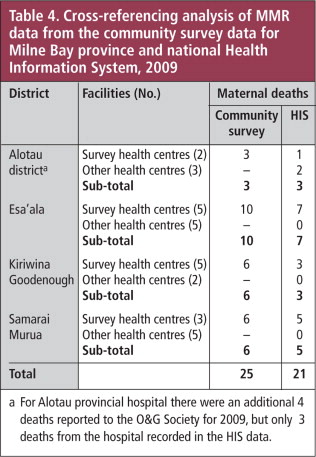

A community-based survey of the villages served by 15 rural health centres in Milne Bay Province was performed by one of the authors (BK) in 2009. He visited the homes of 25 women whose deaths had been notified to the provincial health authority as pregnancy-related by nurses in rural health centres; there were a further four maternal deaths in the provincial hospital (Alotau) that year. This survey covered approximately 45% of births in Milne Bay for 2009.Footnote* Verbal autopsies were conducted to verify that each death was ‘maternal’ as per the accepted definition. These dataCitation11 along with the records of the Alotau provincial hospital allow for the most accurate estimate of maternal deaths for a province for 2009 (summarized in Table 4).

The proportion of facility-based, supervised births in each of the 20 PNG provinces and 89 districts was calculated by using the estimate of current population from forward estimates from the 2000 census. Expected births were calculated from population data and applying the estimates of crude birth rate from the 2006 DHS. Reported facility-based, supervised births for each province were derived from national HIS data, and fertility estimates from the 2000 Census and the 2006 Demographic Health Survey.

Results

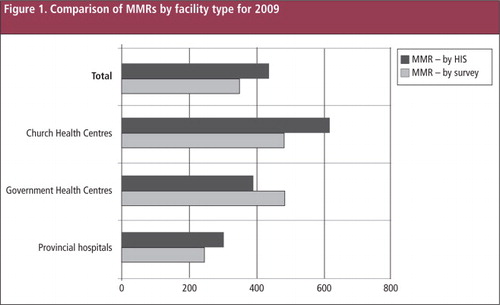

Data for facility-based, supervised births and numbers of maternal deaths are set out by hospital and rural health facilities (church agency and government-run) for all 20 provinces in Table 2. These data were derived from a postal survey with e-mail and phone follow-up in November 2010 and provincial visits in 2011. It was possible to retrieve 2009 data from all 20 provincial hospitals, 76% of government rural health facilities and 88% of church agency health facilities. The calculated MMRs by this survey were 245 for provincial hospitals, 534 for government health centres and 624 for church agency health centres. This means that the facility-based MMR by this survey was 394.

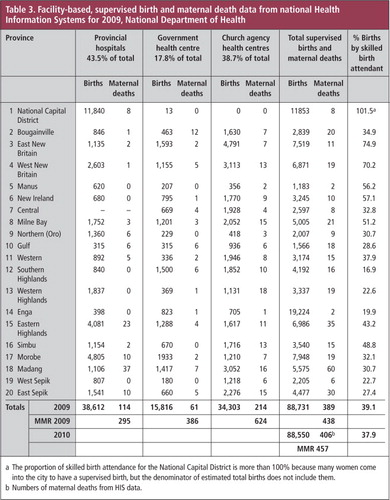

Table 3 shows facility-based supervised births and maternal deaths as recorded in the HIS data by province and type of facility for 2009. The proportion of supervised birth by province was calculated and is also shown in Table 3. From the HIS data, the MMR is 295 for provincial hospitals, 386 for government health centres, and 624 for church agency health centres, giving an overall MMR for supervised births from HIS data of 438.

For 2009, using the Demographic Health Survey (2006) calculation of the crude birth rate (32/1,000), we estimated that there were 227,188 births in PNG. The best estimate of supervised births was 88,731, giving an overall supervised rate (both facility- and non-facility-based)Footnote* of 39.1% with a provincial range of 16.9% (Southern Highlands) to 74.9% (East New Britain).

Table 5 provides a summary of the various estimates of maternal death numbers and MMRs for 2009, 2010 and 2012. The provincial hospitals’ MMR was 245 in our survey and 295 from the HIS data. There was also consistency between the MMRs for church agency health centres in our survey and from the HIS data (both 624), while the MMR figures for government rural facilities were 534 in our survey and 386 from the HIS data. The 12% of rural facilities that failed to report to the national HIS hub for at least one month of 2009 were predominantly government facilities; government facilities were also more likely to omit mention of maternal deaths. This probably accounts for the fact that our survey found more maternal deaths than reported to the national HIS. The higher figures for maternal deaths reported by church agency rural facilities could be due to the fact that rural people are more likely to try and get to a church agency health facility when something goes wrong in labour, and the fact that church agency facilities reported more consistently to HIS. In addition, some of the maternal deaths reported by church agency rural health facilities were from mobile outreach clinics operating within the catchment area of the health facility and actually occurred in the community or on the way to the facility.Footnote†

In summary the numbers of facility-based maternal deaths in PNG give a facility-based MMR for 2009 of 394 by our survey and 438 by HIS data (and for 2010 and 2012, 460 and 329 respectively by annual HIS data).

is a bar graph comparing the MMRs for the three different kinds of facilities derived from HIS data and from our survey.

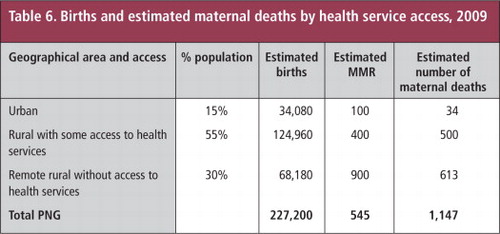

Provincial hospital data for women who were pre-booked into the service where they delivered shows an MMR of approximately 100.Citation11,12 Fifteen per cent of women live in urban areas in PNG.Citation13 The MMR for women who live in rural areas but who can access a basic health facility for supervised birth (and stand a chance of being referred to hospital if a life-threatening emergency occurs) is about 400: about 55% of the population live in these areas of the country.Citation10,14–16 And for the 30% who live in remote rural areas and have no functional access to health services, the MMR is estimated to be about 900.Citation10 Synthesizing this information an attempt was made to estimate the numbers of expected maternal deaths (and associated MMRs). Thus, assuming an MMR for urban areas of 100, for rural areas with road access to a facility to be 400, and for remote rural areas with no road access to a facility to be 900, there would have been about 1,147 maternal deaths in 2009 in PNG. This calculation would give a national MMR of 545. These figures are tabulated in Table 6.

The maternal mortality data for Milne Bay province in 2009, based on the figures from the community-based survey, were four deaths amongst 1,650 women who had supervised births at Alotau Hospital (MMR 242), and 25 deaths amongst an estimated 4,257 womenFootnote** who gave birth in the catchment areas of 15 rural health centres of Milne Bay that provided information in the survey (MMR 587). The 2009 HIS data for Milne Bay counted 21 maternal deaths (3 in Alotau Hospital and 18 from rural districts). The fact that the 15 rural health facilities which were part of the Kirby Milne Bay community survey recorded 25 maternal deaths and the 15 other health facilities only 2 (to HIS) probably indicates that many rural maternal deaths are being missed by HIS data collection systems. The facilities which were not part of the community-based survey are in fact some of the more remote and less accessible parts of Milne Bay province; as such they could be expected in fact to have a higher ratio of maternal mortality. In total, 25 maternal deaths were recorded in our survey and 21 by HIS; all the HIS maternal deaths were included in our survey and 2 deaths from one very remote health facility reported to HIS were not reported in our survey.Footnote* Cross-referencing of these three data sources is tabulated in Table 5.

Discussion

Our facility-based count of maternal deaths estimated a facility-based MMR of 394. Maternal deaths recorded by the national HIS give an MMR of 438 for the same year (2009). The community-based survey in Milne Bay province counted 29 maternal deaths, giving an estimated MMR of 587. The Milne Bay province experience demonstrated that when there is a focus on collecting information about maternal deaths, many more deaths are identified.

Our study has a number of limitations: deaths in early pregnancy may not have been reported as maternal deaths in the facility audits, and the facility-based births only accounted for about 40% of all births. We had access to community-based maternal death audits from only one province. However, those findings demonstrated a far higher proportion of maternal deaths in settings where facility-based deliveries were not possible: this has been the case in previous community maternal death studies too.Citation17 Our facility-based MMR is considerably higher than the overall MMRs calculated by the UN MMEIG and IHME in all years except for the first estimate published in 1996;Citation14 it is likely that MMRs for the ˜60% of unsupervised births – particularly those taking place in remote areas where there is little chance of access to treatment when obstetric problems arise – will be higher again.

In the 1980s, health professionals and decision makers in PNG were up in arms that the World Health Organization had ascribed such a high MMR to PNG; it was felt to be somehow insulting. Given that the health services in PNG, particularly rural health services, have deteriorated so profoundly over the past 20 years,Citation7 the PNG health community is now surprised that both the IHME Group and the UN MMEIG have estimated the MMR to be low in comparison to the figures estimated locally. The proportion of women accessing a facility-based, supervised birth has decreased from about 60% soon after independence in 1975 to 37–41% in 2009Footnote*; in addition, there has been little change in the total fertility rate over the same period.Citation3,4,18 There is understandable concern that under-estimation of the MMR will lead to government and development partner complacency with regard to reproductive health services planning, provision, monitoring and evaluation.

One explanation for the significantly lower estimates of MMR for PNG by international groups is that the mathematical models being used to calculate them are highly influenced by economic indicators. GNI and GDP have risen a great deal in PNG over the past ten years because of the resources boom produced by mineral, oil and gas exploration and extraction, which has, however, produced a very uneven distribution of wealth in the country.Citation9,19

We suggest that the use of GNI or GDP per capita as independent variables in a mathematical model to estimate MMR should be accompanied by some measures of economic inequity and access. In a recent study of ‘geographic inequities and poverty’ and the relationship to under-five mortality in PNG, it was found that mortality was strongly correlated with poverty levels and access to services at the district level.Citation9 Another PNG study found that poverty was related to low access to infrastructure, and proposed that the determinants of poverty were poor access to services, markets and transportation.Citation19

The view that women will go to a facility when something goes wrong during a home or village birth (and thereby increase the facility-based MMR) is not the case in PNG. Surveys show that women mostly want to deliver in facilities, but deliver at home because they are unable to get to the facility of their choice (or any facility), once labour commences. These women find it even more difficult to access a first referral-level facility when a life-threatening obstetric emergency arises.Citation20 Moreover, approximately 30% of PNG’s population live in very remote rural areas and do not have access to any health facility.Citation21 Indeed 2009 national HIS data show that 35% of women never attend an antenatal clinic during their pregnancy. The figures from our community survey in Milne Bay province (MMR 687), and 1980s data from Simbu provinceCitation17 indicate that the MMR for PNG women who deliver at home may be as high as 600–1200. The risk of maternal death in areas where there is no access to health services is not likely to have decreased since the 1980s. This is substantiated by the fact that although the total fertility rate nationally has only slightly decreased from 4.8 to 4.4 between 1996 and 2006, it remains unchanged at about 6 in rural and remote parts of the country.Citation3,4

The 1998 WHO Maternal Mortality Global Factbook estimated that in the past, levels of maternal mortality were as high as 1.4% when women had neither antenatal care nor supervised labour and delivery with timely access to emergency obstetric care if required.Citation18 In a study published in 2005 of ‘near miss’ events in African hospitals, Filippi found that near-miss incidence varied from 1.2 to 22.9 cases per 100 deliveries, while the maternal mortality ratio ranged from below 100 to above 3,000 maternal deaths per 100,000 live births. Clearly maternal mortality ratios can be very high in places where there is poor general health, high fertility rates and no pregnancy care. These conditions prevail in the 30% of PNG where women have virtually no access to pregnancy care.Citation22

Putting all this together (Table 6) we can surmise that the MMR for PNG is probably not less than 500. Clearly the figures in Table 6 cannot be assumed to be ‘accurate’ in the scientific sense, but they are derived from all the local empirical data that we have. And, the figure of 500 is not inconsistent with the upper range of the standard error for the UN MMEIG and IHME data for 2000–2010; it is also within the error of PNG DHS data. It can of course be claimed that with the wide confidence intervals in both the modelled estimates and uncertainty in the facility-based data, it is not possible to be sure whether the MMR is improving or deteriorating; however, this conclusion is not practically useful. In the absence of more comprehensive mortality studies, the women of PNG would be better served if a locally accepted MMR of about 500 guided maternal health policy. For the future, a Reproductive Age Mortality Study (RAMOS) would be much more helpful than another poorly sampled DHS or further estimates from modelling using covariates that do not associate well in PNG with health parameter outcomes.

One rationale for developing international estimates for all countries is the legitimate desire for a degree of comparability over time and between countries. However, from a country perspective what matters is being able to measure and monitor our own status and trends, and the ability to generate local data for local advocacy and service planning. Indeed, governments have a responsibility to allocate adequate resources to the production of sound and reliable data on an ongoing basis, and international agencies should support them in doing so.

The international agencies could do far more to engage productively with countries in trying to establish reasonably accurate maternal mortality estimates. Most developing countries would need assistance in developing capacity for more comprehensive and accurate maternal data collection as well as timely collation, analysis and reporting. Moreover data must be turned into useful information for those who need it, when they need it, to plan and operationalize good quality, equitable service delivery with the resources available.

Over a decade ago, WHO promoted the concept of ‘Beyond the Numbers’,Citation23 which promotes the use of maternal death reviews in order to learn lessons about how such deaths can be averted. In Papua New Guinea we have found that the section of the national maternal mortality reporting form that produces the most useful information is the part where the reporting health worker is asked to ‘tell the story of how the woman died’. These stories often reveal not only the medical reason for the death, but the logistic, social and resource challenges that led to her demise, thus providing information that allows analysis of the death in terms of the ‘three delays’. Every maternal death is also a valuable learning/teaching opportunity. With the view that no maternal death is inevitable or unavoidable, at the very least health workers should learn from their own and others’ mistakes. When a maternal death reveals deficiencies in community decision making or difficulties in arranging referral, the death can be a useful advocacy tool for community education and to convince decision makers that referral systems need to be improved.

A maternal death is never a good thing, but at least if every death can be accurately recorded and audited perhaps it is not wasted either.

In conclusion, it is important to analyze data from national health information systems on a regular and systematic basis so as to be able to better inform local decision-making. Moreover, such local data need to be made accessible in the public domain: too often HIS data is stored, not analyzed and rarely disseminated to either local or international stakeholders. At the same time, it is important to work with international agencies to find better ways of making effective use of even incomplete local data. This could help reduce the discordance between what has been happening in terms of trends in independent variables (particularly maternal and child health parameters), with GNI per capita increasing while other key variables are either stagnant or declining. Better collaboration between international agencies working on health metrics and national and local experts would not only improve the quality of internationally developed estimates, but would also greatly enhance country ownership and build capacity to generate, analyze and interpret key health data.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the co-operation of the health workers of PNG who responded to requests for information about maternal mortality in their facilities over more than two years. Our thanks also to Carla AbouZahr for data, advice and editing.

Notes

† Nonetheless, it is highly unlikely that HIS maternal mortality counts contain double entries because each HIS officer only reports from their own local facility.

* The 1996 PNG DHS was sponsored by AusAid and the 2006 DHS by the Asian Development Bank.

* These data are available with sub-analysis for ‘Born Before Arrival’, and whether the birth was supervised by a trained health worker within the facility or outside the facility.

* Provincial hospital reporting rates to the O&G Society AGM were 12/20 in 2009, 14/20 in 2010 and 13/20 in 2011.

† ObGyns reporting to the AGM of the PNG Society of O&G are also careful to report all maternal deaths which occur in their facility and not only those which occur in the ob-gyn wards.

* The estimate of 45% of births being within the catchment area of the facilities surveyed comes from provincial health estimates of health centre coverage.

* HIS data indicate that less than 1% of supervised births were non-facility-based.

† Noted on the survey forms faxed back to the study by church agency health centres.

** Taking extrapolated 2000 census population data for the catchment areas and assuming a crude birth rate of 34/1,000 (DHS 2006).

* Although HIS data are unlinked, it was possible to link our Milne Bay province survey data by demographic characteristics and site of reporting.

* 37% by HIS data and 41% by Sector performance annual review (2012) for 2009. Diminishing rates of supervised birth in Papua New Guinea from 1980 to 2010 are documented by annual HIS data; DHS 1996 and 2006 data show static supervised birth data. However, the latter data count births at home with a village birth attendant in the supervised birth proportion. DHS data also indicate increasing levels of child malnutrition, showing that rising GNI has not filtered down to ordinary people.

References

- Revised 1990 Estimates of Maternal Mortality: a new approach by WHO and UNICEF. Geneva: WHO, April 1996.

- MC Hogan, KJ Foreman, M Naghavi. Maternal mortality for 181 countries, 1980–2008: a systematic analysis of progress towards Millennium Development Goal 5. Lancet. 375(9730): 2010; 2009–2023.

- PNG National Statistics Office. 1997 Demographic Health Survey of Papua New Guinea, 1996.

- PNG National Statistics Office. 2009 Demographic Health Survey of Papua New Guinea, 2006.

- R Lozano, H Wang, KJ Foreman. Progress towards Millennium Development Goals 4&5 on maternal and child mortality: an updated systematic analysis. Lancet. 378(9797): 2011; 1139–1165.

- C. AbouZahr. New estimates of maternal mortality and how to interpret them: choice or confusion?. Reproductive Health Matters. 19(37): 2011; 117–128.

- Ministerial Task Force on Maternal Health in Papua New Guinea. Report. National Department of Health, PNG, May 2009.

- WHO UNFPA UNICEF World Bank. Trends in maternal mortality 1990–2010, Inter-Agency Estimates of Maternal Mortality, 2012. www.unfpa.org/webdav/site/global/shared/documents/publications/2012/Trends_in_maternal_mortality_A4-1.pdf

- AE Bauze, LN Tran, K-H Nguyen. Equity and geography: the case of child mortality in Papua New Guinea. PLoS One. 7(5): 2012. http://www.plosone.org/article/info%3Adoi%2F10.1371%2Fjournal.pone.0037861.

- B. Kirby. Too far to travel: maternal mortality in Milne Bay Province. O&G Magazine. 15(4): 2011; 57–59.

- Department of Obstetrics Gynecology, Port Moresby General Hospital. Annual reports 1985–2011.

- PNG Society of Obstetrics & Gynecology. Annual reports 1985–2011.

- National Statistical Office Papua New Guinea. 2000 census data. 2006.

- Maternal Mortality in 2000. Estimates developed by WHO, UNICEF and UNFPA. 2004; WHO: Geneva.

- GDL Mola, AI. Aitken. Maternal mortality in Papua New Guinea 1976–83. Papua New Guinea Medical Journal. 27(4): 1984; 265–271.

- GDL. Mola. Maternal health services and maternal mortality in Papua New Guinea. Papua New Guinea Medical Journal. 28(4): 1985; 368–372.

- GDL. Mola. Maternal death in Papua New Guinea 1984–1986. Papua New Guinea Medical Journal. 32(1): 1989; 27–31.

- Countdown to 2015, Maternal, Newborn and Child Survival: Papua New Guinea presentation 2011. http://www.countdown2015mnch.org/country-countdown/country-presentations.

- J Gibson, S. Rozelle. Poverty and access to roads in Papua New Guinea. Economic Development and Cultural Change. 52: 2003; 159–185.

- Kirby B. Too far to travel, maternal mortality in Milne Bay Province: thesis for the Post-Graduate Diploma of ObGyn, UPNG. PDF available from the author ([email protected]).

- Government of Papua New Guinea, Papua New Guinea National Health Plan 2011–2020. Resource documents. PNG Government Printer, 2011.

- V Filippi, C Ronsmans, V Gohou. Maternity wards or emergency obstetric rooms? Incidence of near-miss events in African hospitals. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavia. 84(1): 2005; 11–16.

- World Health Organization. Beyond the Numbers: reviewing maternal deaths and complications to make pregnancy safer. 2004; WHO: Geneva.

- Maternal mortality in 2005: estimates developed by WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA, World Bank. Geneva: WHO, 2007.